Abstract

The world’s population is aging, with the number of older adults projected to increase dramatically over the next two decades. This trend poses major challenges to health care systems, reflecting the greater healthcare utilization by and more comorbid conditions among elderly adults. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a substantial concern in the elderly, with both an increasing incidence of treated kidney failure with dialysis as well as a high prevalence of earlier stages of CKD. Given the high burden of risk factors for CKD, the high prevalence of CKD in the elderly is not surprising, with the rise in obesity, diabetes and hypertension in middle-aged adults likely foreshadowing further increases in CKD prevalence among the elderly. It is now commonly agreed that the presence of CKD identifies a higher risk state in the elderly, with increased risk for multiple adverse outcomes, including kidney failure, cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, and death. Accordingly, CKD in older adults is worthy of attention by both health care providers and patients, with the presence of a reduced GFR or albuminuria in the elderly potentially informing therapeutic and diagnostic decisions for these individuals.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, elderly, glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

When the Medicare end-stage renal disease (ESRD) program in the United States was funded in 1973, individuals receiving dialysis comprised the youngest, healthiest, most educated and most highly motivated portion of the kidney failure population. While this pattern remains the rule in many less wealthy nations, the introduction of systematic funding of ESRD care in the US and other industrialized nations increased the availability of kidney replacement therapies to all segments of the population, including the elderly [1]. Four decades later, individuals 65 years old and older now comprise the most rapidly growing segment of the ESRD population in wealthier countries [2]. As such, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a substantial concern in the elderly, with both an increasing incidence of treated kidney failure with dialysis as well as a high prevalence of earlier stages of CKD [3]. Given the high burden of risk factors for CKD in the middle-aged population, the high prevalence of CKD in the elderly is not surprising (figure 1) and likely foreshadows a further increase in CKD prevalence among the elderly.

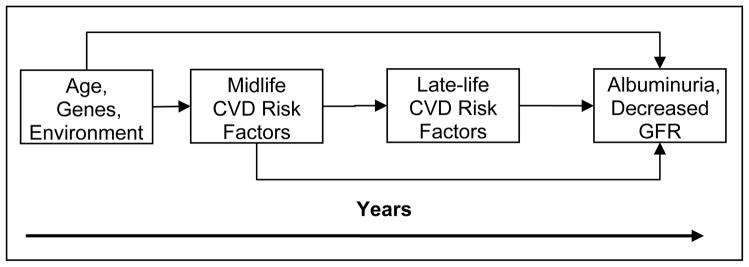

Figure 1.

Concept model of factors modifying the prevalence of CKD in late life. GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Many cases of CKD in the elderly manifest without a readily apparent cause; this is particularly true for CKD defined only by reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and has appropriately generated many questions and much controversy about whether a moderate reduction in estimated GFR without other evidence of kidney damage in the elderly should be designated as a disease [4]. Despite this controversy, there is consistent evidence that reduced estimated GFR (eGFR) and albuminuria, either separately or in combination, identify a higher risk state in the elderly as is demonstrated in the many studies that demonstrate an association for both lower eGFR and albuminuria with both a higher prevalence and an increased incidence of adverse outcomes in elderly individuals, including kidney failure, cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, and all-cause mortality [5–8], providing support for the current definition of CKD in the elderly.

In this article, we review the changing demographics of the middle-aged and elderly population both in the United States and worldwide. In that context, we discuss the prevalence of both earlier stages of CKD as well as kidney failure in the elderly, including a discussion of creatinine- versus cystatin C-based estimates of GFR. Additionally, we examine the prognosis of elderly patients with CKD, focusing on vascular related complications that are more common in the elderly. Finally, we stress that CKD in older adults is worthy of attention by health care providers and patients, with the caveat that, given the many competing comorbid conditions in elderly individuals with CKD, it is imperative to take an individualized approach to their clinical care and decision-making.

The Aging Population and Accumulated Risk Factors

The world’s population is aging. Currently it is estimated that people over 65 years old number approximately 420 million or about 7% of the global population [9]. It is projected that by 2050 there will be over 1.5 billion people worldwide 65 years old and older, reflecting an increasing number of elderly individuals in both developing and developed countries [10][11]. Continuing expansion of the elderly population poses major challenges to the health care system [9]. In the US, people older than 65 years of age have an average number of 3.5 chronic illnesses per person, with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and CVD itself particularly common [12].

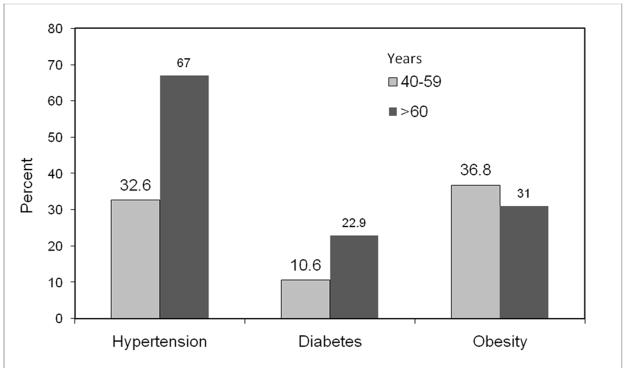

An elderly population that has a high rate of comorbid disease is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Given the prevalence of obesity of over 30% in middle-aged and elderly adults [13], it is not surprising that approximately 11% of middle-aged adults have diabetes and 33% have hypertension, with the prevalence of these conditions increasing to 23% and 66%, respectively, by age 60 (Figure 2) [14, 15]. In the United States, these rates are highest among racial and ethnic minority populations, and in people with lower socioeconomic status [16]. This trend is similar in many developing countries, where chronic diseases are a major cause of morbidity and mortality [17].

Figure 2.

Prevalence of chronic conditions among adults by age in 2002–2003

Epidemiology of CKD in the Elderly

Chronic Kidney Disease (Stages 1–4)

Definition and Ascertainment

CKD is defined by GFR less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and/or kidney damage for three or more months. The presence of albuminuria is most commonly used to define kidney damage, while GFR is usually estimated using equations that include a filtration marker, such as serum creatinine, in conjunction with demographic characteristics that account for factors that affect creatinine generation. The most common creatinine-based equation currently in use is the 4-variable MDRD Study equation, although a newer equation, the CKD-EPI equation, is more accurate, particularly at higher levels of eGFR [3]. Critically, the performance of creatinine-based estimating equations remains insufficiently evaluated in older adults, in whom there may be a high prevalence of chronic disease associated with alterations in muscle mass and diet resulting in overestimation of measured GFR and underestimation of CKD prevalence. Cystatin C is a filtration marker that may be less related to muscle mass than creatinine, and therefore may have a particular advantage in the elderly [18, 19].

Prevalence

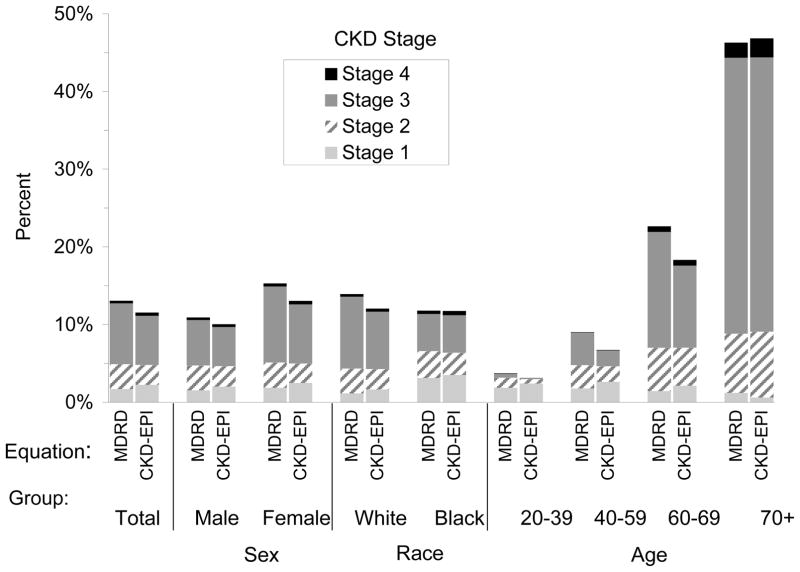

In participants 70 years old and older in the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey (NHANES), the prevalence of CKD determined with the CKD-EPI equation is 46.8% compared to 6.71% in those between than 40–59 years of age (Figure 3). Using the MDRD Study equation, the prevalence of CKD in those older than 70 years of age was similar at 46.3% [3]; the more accurate CKD-EPI equation confirms the higher prevalence of CKD in the elderly. The higher prevalence of CKD in the elderly reflects a high prevalence of both eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2 and albuminuria [20]. CKD prevalence in other countries is similarly high, with as many as 20% of the Japanese [21] and 13% of the Beijing population classified as having CKD [22].

Figure 3.

Distribution of estimated GFR and chronic kidney disease (CKD) prevalence by age in NHANES 1999–2004. MDRD and CKD-EPI refer to the MDRD Study and CKD-EPI equations, respectively. Reprinted with permission [20].

Etiology

The cause of CKD often is not readily apparent in many elderly patients. Epidemiological evidence suggests that vascular disease may be the predominant etiology for CKD in this population. Numerous CVD risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension and obesity, are prevalent in patients with CKD and are associated with albuminuria and decreased GFR [23]. As is posited in Figure 1, the presence of CVD risk factors and CVD itself in middle age may lead to the development of CKD in later life. Pathologic lesions associated with CVD risk factors are predominantly vascular and include diabetic glomerulosclerosis, hypertensive nephroarteriolar sclerosis, and obesity-related FSGS [24–27], lesions commonly seen in biopsies of elderly kidneys[28–30]., In contrast, pathologic studies of older kidney donors, who are screened to be free from overt vascular disease, show higher amounts of glomerulosclerosis and lower levels of measured GFR compared to younger kidney donors [31], which suggests these pathological changes may occur as part of the normal aging process and not related to vascular disease. However, donor evaluations do not include screening for subclinical vascular disease, and, given the ubiquitous nature of atherosclerosis in our society, subclinical disease may be present. The lack of diagnostic tests able to readily evaluate the kidney microvasculature limits our understanding of the pathophysiology that may occur with aging or secondary to vascular insults earlier in life.

Progression

Regardless of the underlying cause of the CKD, the elderly are at high risk for further kidney injury and therefore progression for CKD. For example, in one study of 10,184 Canadian community dwelling elders 66 years of age or older with one or more outpatient serum creatinine assessments, approximately 40% of people with eGFR between 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 had a decline in eGFR of greater than 5 mL/min per 1.73m2 over a 2 year period [32]. Similarly, analyses of data from the Cardiovascular Health Study, a population based sample of people 65 years and older in the US, shows that a substantial proportion of elderly people have progression of CKD, with 16% and 25% of the cohort having an annual decline of greater than 3 ml/min per 1.73 m2 estimated using creatinine-based and cystatin C-based equations, respectively [33].

Major risk factors for progression include hypertension and diabetes, common in the elderly, as described above). Additionally, the elderly are at high risk for development of acute kidney injury (AKI), which is also a major risk factor for progression, for several reasons. First, a high prevalence of co-morbid diseases, such as prostatic hypertrophy or congestive heart failure, can directly induce AKI. Second, medications and medical interventions commonly used for treatment of co-morbid conditions may either cause or predispose to the development if AKI. Third, structural changes in the kidney that often occur with aging may preclude successful compensation for acute decreases in GFR. Data from a large health care system demonstrate that, on average, patients developing AKI are approximately 10 years older than those who do not develop AKI [34], and elderly patients developing AKI are less likely to recover kidney function [35].

Dialysis

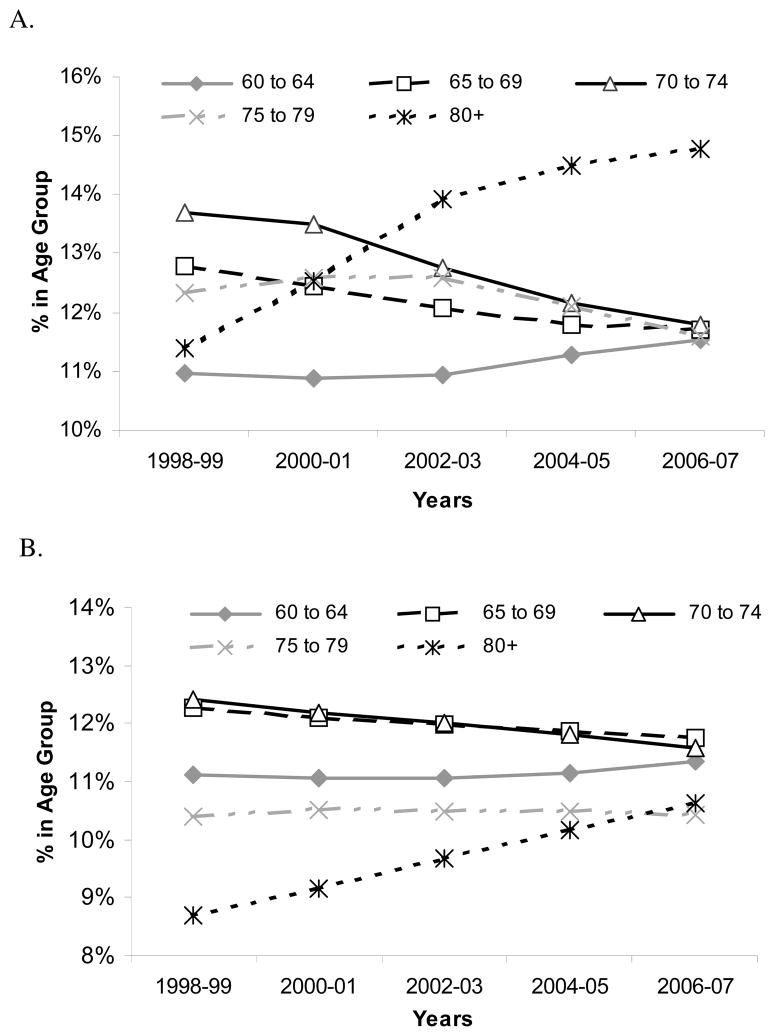

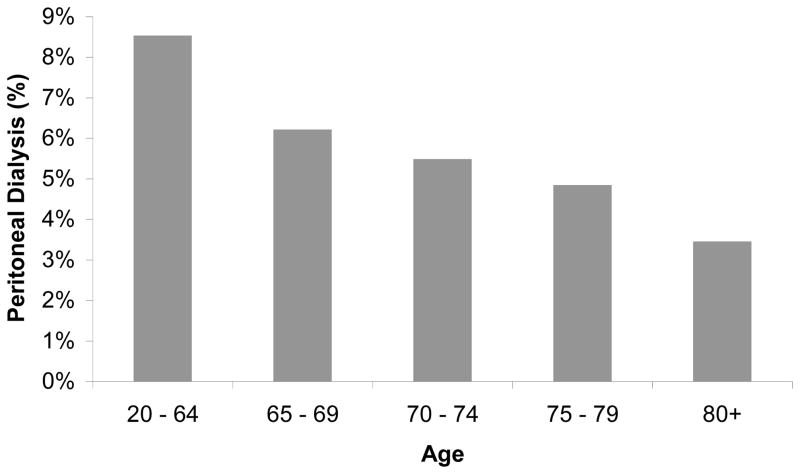

In the US, the increase in the dialysis population is driven by the increased incidence of octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis (Figure 5), with the 32,000 incident dialysis patients 80-years-old and older in 2007 representing a 60% increase from 1998 [2]. These oldest old comprise only a small portion of the elderly hemodialysis population; in 2006–07 patients 65-years-old or older comprised half of the incident adult US dialysis population. Prevalence data reveal similar trends (Table 1). Older dialysis patients differ from younger patients in other important ways, typically initiating dialysis at higher eGFR levels and lower body mass index, having more comorbid conditions, and higher admission and mortality rates (Table 1), and are less likely to be treated with peritoneal dialysis (Figure 4) [2]. These characteristics and treatment trends are reflected in extraordinary first year total medical costs, which approached $115,000 in 2005 for US hemodialysis patients age 67 and older [36].

Figure 5.

Incident (A) and prevalent (B) hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in the United States over the past 10 years. Incidence and prevalence rates for patients between age 20 and 60 have remained stable at 37.7–38.8% and 44.3–45.1%, respectively, over this decade. Figures A and B are derived using data supplied by the USRDS RenDER

Table 1.

Characteristics of prevalent dialysis patients in the US by age, 2007.

| Age | <65 n=203,207 |

65–69 n=42,720 |

70–74 n=39,443 |

75–79 n=34,946 |

80+ n=42,380 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||||

| White | 49.2% | 58.0% | 61.4% | 67.9% | 73.8% |

| African American | 44.5% | 35.4% | 32.2% | 26.1% | 20.6% |

| Asian | 4.5% | 4.9% | 4.9% | 5.1% | 4.9% |

| Native American | 1.7% | 1.6% | 1.4% | 0.9% | 0.6% |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 16.9% | 15.7% | 14.5% | 11.8% | 8.6% |

| Cause of ESRD | |||||

| Diabetes | 41.6% | 56.5% | 52.9% | 44.8% | 32.2% |

| Hypertension | 25.0% | 23.9% | 27.5% | 33.4% | 45.2% |

| Glomerulonephritis | 13.9% | 6.1% | 5.9% | 6.4% | 6.3% |

| Other | 15.9% | 10.6% | 10.7% | 11.7% | 11.3% |

| Unknown | 3.6% | 2.8% | 3.1% | 3.7% | 4.9% |

| Characteristics | |||||

| Body mass index | 28.7 | 28.6 | 27.6 | 26.6 | 25.2 |

| eGFR | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 10.1 |

| Hemoglobin | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Clinical Events | |||||

| Admission Rate* | 1,818 | 1,907 | 1,967 | 1,985 | 2,040 |

| Hospital Days^ | 12.2 | 14 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 14.0 |

| Death Rate | 131.3 | 226.7 | 270.5 | 334.0 | 448.1 |

Individuals missing data on age, sex or race were not included in the table. Other causes of ESRD include those who were missing an entry for that field (0.2% of the entire population). Clinical characteristics are derived from 2728 data and refer to the value at the time of dialysis initiation. Body mass index in kg/m2; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in mL/min per 1.73m2, and hemoglobin in g/dL.

, unadjusted per 1000 patient years

unadjusted per patient year

Figure 4.

Proportion of prevalent dialysis patients in the US treated with peritoneal dialysis in 2007.

In countries where funding is available, given the aging population, a continued growth in the elderly dialysis population is anticipated. These changing demographics mandate a discussion of societal goals and priorities. A recent study noted that elderly nursing home residents initiating dialysis in the US experienced a marked decline in functional status during the period surrounding the initiation of dialysis, and, by 1 year after the start of dialysis, only one of eight nursing home residents had functional capacity similar to the predialysis level [37]. Another study examined 206 individuals with kidney failure requiring dialysis who were discharged to a long-term care hospital and noted that only 31% returned to home; older age was an independent predictor of failing to be discharged home [38]. These poor outcomes strongly suggest that alternative paths, such as decision for palliative care rather than initiation of dialysis, should be incorporated in discussions in both the acute as well as chronic pre-dialysis settings [39].

Vascular Consequences of CKD

Elderly people with CKD are far less likely to develop kidney failure than to die of other cause, which is most often related to vascular disease. As such, recognition of vascular disease is imperative to the therapeutic approach to this population [40].

Coronary and Peripheral Vascular Disease

CVD is common in all stages of CKD, with the high prevalence of CVD in incident dialysis patients suggesting development of CVD prior to the onset of kidney failure. Individuals with CKD in the United States, as defined by claims data, have three times greater hospitalization rates for myocardial infarction, stroke and arrhythmia than those without CKD [41]. This pattern persists among the elderly, with studies consistently demonstrating a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease and CVD risk factors among individuals with reduced kidney function [6, 7, 42]. For example, among patients with eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73m2 in CHS, 26% had coronary artery disease, 8% had heart failure and 55% had hypertension at baseline, while in those without CKD 13% had coronary artery disease, 3% heart failure and 36% hypertension [6].

Most cohort studies have consistently demonstrated an association between reduced levels of eGFR and incident and prevalent CVD in both younger and older people (e.g. [6][43, 44]). However, direct comparison among studies, and particularly across ages, is not straightforward, and therefore there are ongoing questions about specific thresholds for risk among different groups. One concern is the use of a reference group of GFR estimated from serum creatinine as ‘greater than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Elderly individuals with this range of kidney function fall into one of two categories: they may truly have normal levels of eGFR or may have lower levels of GFR but falsely elevated levels of estimated GFR due to low muscle mass secondary to chronic illness. Accordingly, this control group is heterogeneous, comprised of individuals with different levels of risk for adverse outcomes, potentially rendering the comparison to individuals with eGFR below 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 less accurate [45]. A second concern in the comparison of risk among younger and older adults is the difference between relative and absolute risk. Because elderly are at a higher risk for most outcomes, even a small increase in relative risk may translate into a large number of individuals facing increased likelihood of adverse events. Finally, as described earlier, creatinine may have limitations as a marker of GFR in the elderly, with several studies in elderly populations examining the relationship between cystatin C and CVD in elderly individuals and noting stronger and more linear associations compared to creatinine based estimates [7, 46]. These methodological concerns limit articulation of a specific threshold for risk in both younger and older adults given available data.

Among dialysis patients, CVD is the single leading cause of mortality, accounting for nearly 45% of deaths at all ages, with approximately 2/3rds of cardiovascular deaths classified as cardiac arrest or arrhythmia [2]. As compared to younger individuals, in older dialysis populations rates of all-cause death and cardiovascular death are more similar to the general population; nevertheless events remain nearly 6-fold higher among elderly dialysis patients than in the elderly general population (Figure 6) [2, 47]. In addition to cardiac disease, peripheral vascular disease in hemodialysis patients is a major comorbid condition, significantly impacting both quality of life and overall survival [48].

Figure 6.

Cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population and dialysis population. Data on dialysis patients was derived from the USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report and reflects events occurring between 2001 and 2006; while data on the general population was derived from the 2008 National Vital Statistics Reports using 2005 data; CVD mortality includes death due to myocardial infarction, pericarditis, atherosclerotic coronary disease, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, valvular heart disease, pulmonary edema, congestive heart failure and cerebrovascular diseases in dialysis patients and is defined by ICD-10 codes I00–I78 in the general population. The youngest age group in the general population is 25–44 years old versus 20–44 in dialysis.

Cerebrovascular Disease and Cognitive Functioning

CKD is a risk state for both cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, likely reflecting the high prevalence of traditional CVD risk factors in patients with reduced kidney function [44]. Cognitive impairment is similarly associated with CVD risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia, with small vessel cerebrovascular disease likely mediating this relationship [49]. Recently, several studies have evaluated the association between cognitive function and kidney disease in elderly individuals. These studies have demonstrated relationships between albuminuria and both cognitive functioning and small vessel cerebrovascular disease [50, 51] as well as between reduced kidney function and cognitive function [5, 52]. Similar findings are present in the dialysis population, where small vessel cerebrovascular disease and cognitive impairment are also common [53, 54]. Reflecting the hypothesized cerebrovascular etiology, cognitive deficits are more apparent in realms of attention, processing and executive functioning – these are domains that are necessary for complex tasks like managing a medication regimen and awareness of the increased prevalence of cognitive deficits in the CKD population is imperative to caring for these vulnerable patients.

Awareness Impacts Management

CKD, and particularly the GFR, may affect diagnostic and treatment decisions for comorbid conditions. An individualized approach is often necessary to incorporate patient’s goals for quality as well as quantity of life. This balance may help clinicians guide selection of the most appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic options.

Knowledge of the level of eGFR is important for such decisions as use of iodinated contrast and gadolinium for imaging studies as well as the selection and dosing of medications [55, 56]. Inappropriate medications or inappropriate doses increase the risk for drug-drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, complications of routine procedures, hospitalizations and death [57]. For example, commonly used medications, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and oral phosphate purgatives, are associated with GFR decline in community dwelling elders [58] [59]. Recent data also demonstrate that patients with CKD are at higher risk for adverse outcomes directly related to care. In analyses of data from the VA, patients with CKD were more likely to have a complication following surgery or episodes of hyperkalemia or hypoglycemia [60, 61]. Education and involvement of primary care physicians, as well as specialists who take care of patients with CKD, such as cardiologists, endocrinologists, and vascular surgeons, are critical to successful implementation of these recommendations[62].

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of comorbid conditions in elderly individuals with CKD, the frequent use of complex medication regimens and multiple medications, and the often aberrant and uncertain metabolism of medications in both elderly individuals and individuals with CKD, treatment decisions will ultimately require a balance of risks and benefits, together with patient goals. Increasing awareness of CKD and its implications in the elderly will assist clinicians in achieving these goals.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript presents data abstracted from the USRDS 2009 Annual Report. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

Financial Disclosure

None

References

- 1.Blagg CR. The early history of dialysis for chronic renal failure in the United States: a view from Seattle. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(3):482–96. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Renal Data System. Excerpts From the United States Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease & End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(1, Supplement 1) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levey AS, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckardt KU, et al. Definition and classification of CKD: the debate should be about patient prognosis--a position statement from KDOQI and KDIGO. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):915–20. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurella TM, et al. Kidney function and cognitive impairment in US adults: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):227–34. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manjunath G, et al. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes in the elderly. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1121–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlipak MG, et al. Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(20):2049–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallan SI, et al. Association of kidney function and albuminuria with cardiovascular mortality in older compared to younger individuals: The HUNT II study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2490–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Older Americans 2008: Key Indicators of Well-Being. 2008 [cited 2009 December 12]; Available from: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2008_Documents/OA_2008.pdf.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health and aging: trends in aging -United States and worldwide. MMWR. 2003;52(6):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 11.P.D. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population ageing, 1950–2050. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider KM, O’Donnell BE, Dean D. Health Qual Life Outcomes. Vol. 7. 2009. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States’ Medicare population; p. 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flegal KM, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2007. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutler JA, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):818–27. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanjilal S, et al. Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971–2002. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2348–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chronic diseases and their common risk factors. [cited 2009 December 1]; The WHO Global InfoBase]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/infobase/report.aspx.

- 18.Stevens LA, et al. Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: a pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(3):395–406. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens LA, Levey AS. Chronic kidney disease in the elderly--how to assess risk. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(20):2122–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Coresh J. Am J Kidney Dis. 3 Suppl 3. Vol. 53. 2009. Conceptual model of CKD: applications and implications; pp. S4–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuo S, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):982–92. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with CKD: a population study from Beijing. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(3):373–84. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cirillo M, et al. Microalbuminuria in nondiabetic adults: relation of blood pressure, body mass index, plasma cholesterol levels, and smoking: The Gubbio Population Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(17):1933–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander MP, et al. Kidney pathological changes in metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(5):751–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.01.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serra A, et al. Renal injury in the extremely obese patients with normal renal function. Kidney Int. 2008;73(8):947–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fogo A, et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans: a report from the African American Study of Kidney Disease (AASK) Trial. AASK Pilot Study Investigators. Kidney Int. 1997;51(1):244–52. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer TW, Bennett PH, Nelson RG. Podocyte number predicts long-term urinary albumin excretion in Pima Indians with Type II diabetes and microalbuminuria. Diabetologia. 1999;42(11):1341–4. doi: 10.1007/s001250051447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindeman RD. Overview: renal physiology and pathophysiology of aging. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;16(4):275–82. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasiske BL. Relationship between vascular disease and age-associated changes in the human kidney. Kidney Int. 1987;31(5):1153–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson S, Brenner BM. Effects of aging on the renal glomerulus. Am J Med. 1986;80(3):435–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan JC, et al. Glomerular function, structure, and number in renal allografts from older deceased donors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(1):181–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Progression of kidney dysfunction in the community-dwelling elderly. Kidney Int. 2006;69(12):2155–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shlipak MG, et al. Rate of Kidney Function Decline in Older Adults: A Comparison Using Creatinine and Cystatin C. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30(3):171–178. doi: 10.1159/000212381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu CY, et al. The risk of acute renal failure in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008:101–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt R, et al. Recovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):262–71. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mau L-W, et al. Trends in Patient Characteristics and First-Year Medical Costs of Older Incident Hemodialysis Patients, 1995–2005. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3) doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.014. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurella Tamura M, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thakar CV, et al. Outcomes of hemodialysis patients in a long-term care hospital setting: a single-center study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(2):300–6. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jassal SV, Watson D. Doc, don’t procrastinate… Rehabilitate, palliate, and advocate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(2):209–12. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Hare AM, et al. Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(10):2758–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins AJ, et al. United States Renal Data System 2008 Annual Data Report Abstract. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(1 Suppl):vi–vii. S8–374. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Hare AM, et al. High prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in persons with renal insufficiency: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2000. Circulation. 2004;109(3):320–3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114519.75433.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Go AS, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiner DE, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality: exploring the interaction between CKD and cardiovascular disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(3):392–401. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Hare AM, et al. Mortality risk stratification in chronic kidney disease: one size for all ages? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(3):846–53. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ix JH, et al. Association of cystatin C with mortality, cardiovascular events, and incident heart failure among persons with coronary heart disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Circulation. 2007;115(2):173–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kung HC, et al. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56(10):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Combe C, et al. The burden of amputation among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(4):680–92. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knopman D, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001;56(1):42–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiner DE, et al. Albuminuria, cognitive functioning, and white matter hyperintensities in homebound elders. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(3):438–47. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barzilay JI, et al. Albuminuria and dementia in the elderly: a community study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):216–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seliger SL, et al. Moderate Renal Impairment and Risk of Dementia among Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(7):1904–11. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000131529.60019.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim CD, et al. High prevalence of leukoaraiosis in cerebral magnetic resonance images of patients on peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(1):98–107. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray AM, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67(2):216–23. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000225182.15532.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Hare AM. The management of older adults with a low eGFR: moving toward an individualized approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):925–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steinman MA, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1516–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fink JC, et al. CKD as an underrecognized threat to patient safety. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(4):681–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gooch K, et al. NSAID use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2007;120(3):280, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khurana A, et al. The effect of oral sodium phosphate drug products on renal function in adults undergoing bowel endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(6):593–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Einhorn LM, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1156–62. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moen MF, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1121–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00800209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevens PE, O’Donoghue DJ. The UK model for system redesign and chronic kidney disease services. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(5):475–82. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]