Abstract

Protein synthesis is a powerful therapeutic target in leukemias and other cancers, but few pharmacologically viable agents are available that affect this process directly. The plant-derived agent silvestrol specifically inhibits translation initiation by interfering with eIF4A/mRNA assembly with eIF4F. Silvestrol has potent in vitro and in vivo activity in multiple cancer models including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and is under pre-clinical development by the US National Cancer Institute, but no information is available about potential mechanisms of resistance. In a separate report, we showed that intraperitoneal silvestrol is approximately 100% bioavailable systemically, although oral doses were only 1% bioavailable despite an apparent lack of metabolism. To explore mechanisms of silvestrol resistance and the possible role of efflux transporters in silvestrol disposition, we characterized multi-drug resistance transporter expression and function in a silvestrol-resistant ALL cell line generated via culture of the 697 ALL cell line in gradually increasing silvestrol concentrations. This resistant cell line, 697-R, shows significant upregulation of ABCB1 mRNA and P-glycoprotein (Pgp) as well as cross-resistance to known Pgp substrates vincristine and romidepsin. Furthermore, 697-R cells readily efflux the fluorescent Pgp substrate rhodamine 123. This effect is prevented by Pgp inhibitors verapamil and cyclosporin A, as well as siRNA to ABCB1, with concomitant re-sensitization to silvestrol. Together, these data indicate that silvestrol is a substrate of Pgp, a potential obstacle that must be considered in the development of silvestrol for oral delivery or targeting to tumors protected by Pgp overexpression.

KEY WORDS: ABCB1, leukemia, multi-drug resistance, P-glycoprotein, silvestrol

INTRODUCTION

The process of protein synthesis is increasingly being recognized as an important therapeutic target in cancer drug development. Many tumors rely on the rapid synthesis of pro-survival proteins, and key factors in the translation initiation process, notably eIF4E, are often mutated, dysregulated, or overexpressed in tumor cells (1–3). Other translation factors are targets of signaling pathways aberrantly activated in cancer (e.g., p70 S6 kinase, 4E-BP; (4,5)). Such affected factors are typically part of the initiation complex, where the majority of cellular regulation of translation occurs. No therapeutic agents are currently available that specifically impact the initiation step in protein synthesis. Inhibitors of the mTOR protein kinase (e.g., rapamycin and analogs) block translation initiation by preventing mTOR-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of the negative regulatory factor 4E-BP1, but this is an indirect effect, and multiple additional cellular pathways are also modulated (6). The development of a more specific agent to block translation initiation may avoid side effects and pro-survival feedback resulting from mTOR inhibition while improving anti-tumor efficacy (6,7).

Silvestrol is a structurally unique cyclopenta[b]benzofuran agent from the plant genus Aglaia, isolated and characterized by Kinghorn and colleagues (8). Silvestrol has nanomolar potency against multiple solid tumor cell lines, as well as in vivo efficacy in a murine P388 leukemia model (8,9). We subsequently demonstrated that silvestrol has potent cytotoxicity against leukemic B cell lines and primary cells, shows selectivity against B cells relative to T cells, and significantly prolongs survival in a murine model of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). This effect appeared to be the result of early depletion of the pro-survival Bcl-2 family member Mcl-1 by translational inhibition, with subsequent mitochondrial damage and apoptosis (10). Importantly, Pelletier and colleagues showed that silvestrol promotes aberrant binding of the RNA helicase eIF4A to capped mRNA, thus preventing productive assembly of the eIF4F translation initiation complex. This group further demonstrated significant in vitro and in vivo activity of this agent, alone and in combination with chemotherapeutic agents, in several tumor models (11–13).

Tumors develop drug resistance through several mechanisms, including upregulation or mutation of the target or by alteration of drug influx or efflux. The adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily is a class of transporters expressed at various levels in a variety of cell types. The major efflux transporters within this family include the multi-drug-resistant gene, isoform 1 (ABCB1, formerly MDR1), and its product P-glycoprotein (Pgp), MDR1-like protein (ABCC1, MRP1), and the breast cancer-resistant protein (ABCG2, BCRP). These pumps metabolize ATP to transport substrates including chemotherapeutic drugs from inside the cell to the extracellular space. Increased or aberrant expression of ABC family member proteins in tumor cells is a well-established cause of drug resistance. Particular to hematologic malignancies, increased Pgp expression is common in multiple leukemia types including ALL, in which approximately 30% of cases are Pgp positive at diagnosis (14). Furthermore, ABC family transporters in the intestinal mucosa can prevent the successful delivery of orally administered anti-cancer agents (15). Understanding the role of drug resistance factors is therefore essential to the development and optimal application of novel therapeutics.

Here, we show that chronic exposure of ALL cells to silvestrol eventually leads to acquired silvestrol resistance as a consequence of elevated levels of ABCB1 mRNA and protein and increased Pgp function. Pharmacologic inhibition of Pgp or downregulation by siRNA resensitizes cells to silvestrol. Collectively, these results identify silvestrol as a Pgp substrate. Together with our separate report of silvestrol pharmacokinetics showing low systemic bioavailability when administered by an oral route, these data indicate that Pgp efflux may be an important obstacle to overcome for the development of oral formulations of silvestrol and targeting tumors protected by this pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The isolation and characterization of silvestrol have been described previously (8). Vincristine sulfate, 2-fluoro-ara-A (active metabolite of fludarabine), and rhodamine 123 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Flavopiridol and romidepsin were provided by the NCI Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Verapamil and cyclosporin A were obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Cells and Cell Lines

The pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line 697 (16) was obtained from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). The HL-60 acute promyelocytic leukemia parental cell line was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The HL-60 derivative HL-60/VCR, expressing high levels of ABCB1/Pgp (17), was provided by Dr. Kapil Bhalla (University of Kansas Cancer Center). HL-60/VCR cells were challenged with the Pgp substrate drug vincristine to confirm resistance. Cell lines were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 with fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 10% for 697 cells and 20% for HL-60 cells. The medium was also supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma). Cells were passaged every 2–3 days to maintain cell density at 1–2 × 105 cells/ml.

Viability Assays

Viability and cell count were regularly monitored by trypan blue exclusion using a hemocytometer. In addition, cell viability was monitored by flow cytometry using annexin/propidium iodide (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) on a FC500 instrument (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide) assays were performed to monitor mitochondrial activity as a surrogate for growth inhibition as previously described (18). All experiments were performed in quadruplicate wells.

Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and cDNA was prepared with SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for Mcl-1, ABCB1, and ABCC1 was performed on an ABI 7900 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Nucleic Acids Shared Resource. TaqMan Universal Master Mix, primers, and labeled probes were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems), using TBP as an endogenous control. Mean threshold cycle (Ct) values were calculated by PRISM software (Applied Biosystems) to determine fold differences according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Pgp Expression and Function

Antibodies used for immunoblots include anti-Pgp (C29; Covance, Princeton, NJ) and anti-actin (I-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Immunoblots were performed using standard procedures. Following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, nitrocellulose membranes were treated with chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and exposed to X-ray film. For surface detection of Pgp, cells were incubated 30 min on ice with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-Pgp antibody (Immunotech, Miami, FL) or a PE-labeled isotype negative control. Cells were washed with cold PBS and analyzed by standard flow cytometry. Pgp function was assessed essentially as previously described (19,20). Cells were incubated with 2.6 μM rhodamine 123 in complete medium for 30 min, washed twice with cold PBS, resuspended in medium up to 2 h, washed again, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

siRNA Experiments

siRNA experiments were performed as previously described (21). ABCB1/Pgp, GAPDH, and scrambled control siRNAs were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA) and used at 3 μM. Based on preliminary time course experiments, the effects of siRNA were measured 48 h after transfection. Untransfected or mock-transfected (no siRNA) cells served as additional controls.

Statistics

Most experiments controlled variation by replicating conditions at the same time, and linear mixed effects models were used to account for dependency among observations within the same replication. Log transformations of the data were applied when necessary to stabilize variances. Data from RT-PCR experiments were first normalized to internal controls, and then linear mixed models were applied. Estimates of treatment effects were based on these models, and 95% confidence intervals of these estimates were reported. Four-parameter logistic regression models were used to calculate and compare IC50 values of drug treatments (22). All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software, v9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Development of Silvestrol-Resistant Cell Line

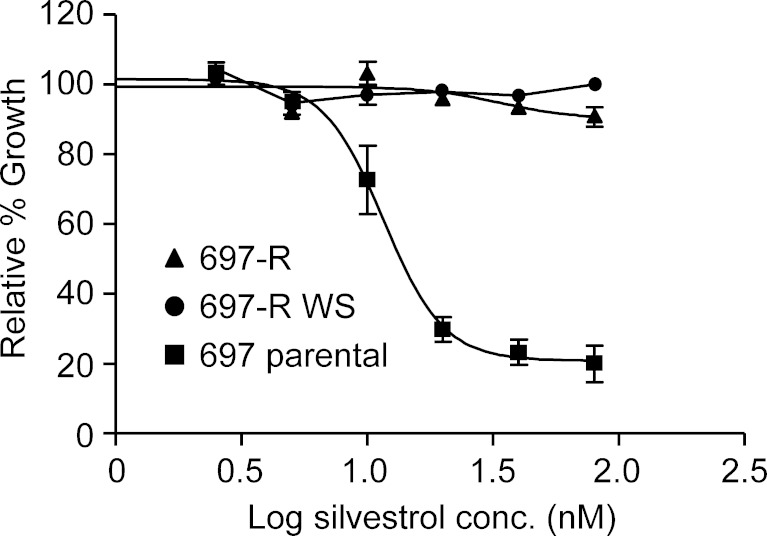

Given the absence of information on potential mechanisms of resistance to silvestrol, we investigated the effect of chronic silvestrol exposure in an ALL cell line, 697. Silvestrol-resistant cells (697-R) were generated through stepwise increasing concentrations of silvestrol from 2.5 to 80 nM over a period of approximately 40 weeks and were subsequently maintained with semi-weekly addition of 80 nM silvestrol. Parental cells were carried in parallel. 697-R cells were morphologically and immunophenotypically identical to the parental 697 cells both as described by the supplier and as validated by us (data not shown), with no observable changes in proliferation rate. Cells were cytogenetically identical as well, with the exception of a t(7;9)(q21.2;p13) balanced translocation found in the 697-R cells (data not shown). To determine whether this event was responsible for the generation of silvestrol resistance, we regenerated 697-R cells by the same strategy, using 697 cells that were cloned by limiting dilution. No cytogenetic differences between the parental and silvestrol-resistant 697 cells were detected in the second generation. Interestingly, however, the second generation required a far longer period to attain similar levels of resistance (24 vs. 44 weeks to attain resistance to 20 nM silvestrol). Therefore, while the previously found translocation may accelerate the development of silvestrol resistance, it is not essential. In the remaining experiments, the first generation 697-R cells were used, although validations using the second generation 697-R cells produced identical results in all cases. To determine whether silvestrol resistance was stable, 697-R cells were incubated in the absence of drug for 14 weeks before being re-challenged with silvestrol at various concentrations for 72 h. As shown in Fig. 1, no difference was noted in silvestrol resistance between cells incubated 14 weeks without drug and cells maintained with biweekly addition of 80 nM silvestrol.

Fig. 1.

Silvestrol resistance in 697-R cells is stable over time. 697-R cells exposed to 80 nM silvestrol every 2 weeks (697-R) or incubated without silvestrol for 14 weeks (697-R WS) were incubated with increasing concentrations of silvestrol for 72 h (N = 3). 697 parental cells were included for comparison. Viability was assessed by MTT assay, and results were calculated relative to time-matched untreated samples

ABCB1/Pgp Expression and Function in 697-R Cells

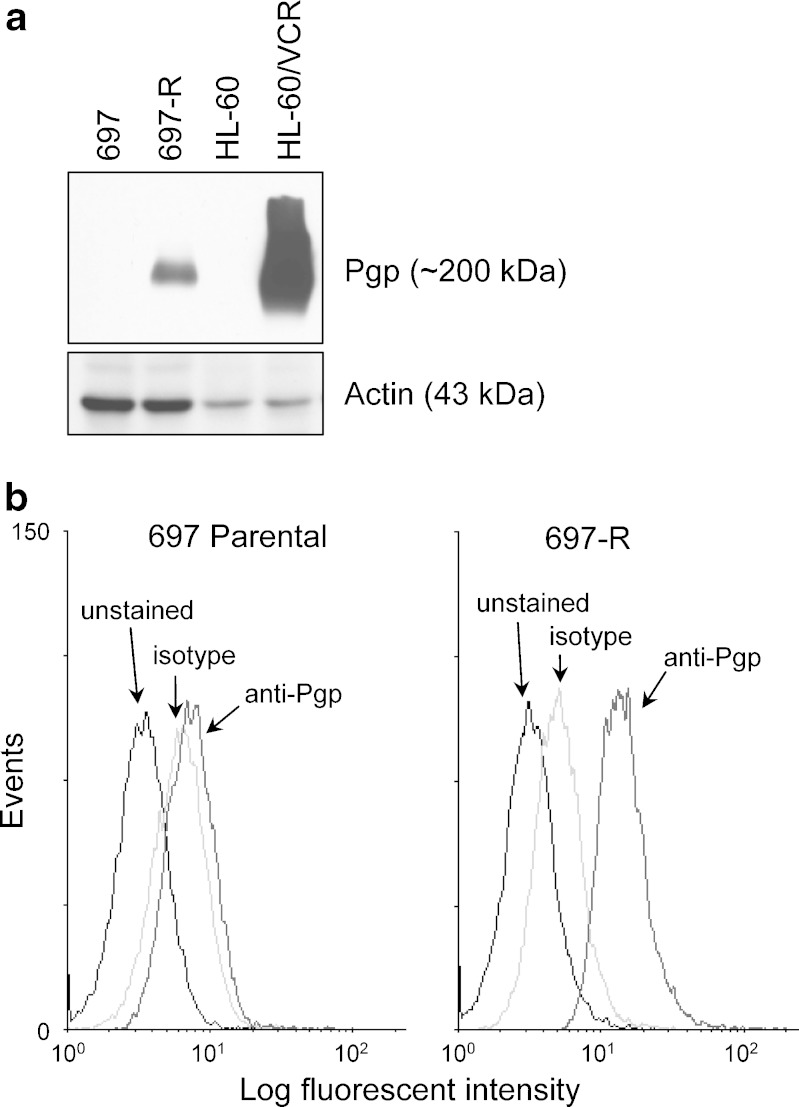

ABCB1/Pgp is known to be upregulated in refractory leukemias including ALL (14). Consequently, ABCB1/Pgp gene and protein expression were assessed in 697-R cells. By real-time RT-PCR, ABCB1 mRNA expression was increased over 28,000-fold in 697-R cells relative to the parental cell line (N = 3); however, the nearly undetectable level in the parental line makes this fold value approximate (cycles required to reach threshold, Ct = 37.4 in 697 vs. 23.1 in 697-R, p < 0.0001). In contrast, mRNA expression of the ABC family member ABCC1 was not significantly different between the 697 and 697-R cell lines (Ct = 24.6 and 24.9, respectively, p = 0.66). We also conducted microarray analysis of 697-R cells vs. the parental line (GeneChip HG-U133 Plus 2, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Of 44 ABC family members represented by 82 probesets, only ABCB1 showed substantial (>1.5-fold) upregulation in the 697-R cells vs. 697 (data not shown). By immunoblot analysis, Pgp protein expression was clearly increased in extracts from 697-R cells compared to 697 cells (Fig. 2a). As controls, extracts from cell lines without (HL-60) or with (HL-60/VCR) overexpression of ABCB1/Pgp (17) were included. To determine whether this increase in Pgp was detectable on the cell surface, Pgp surface expression was assessed by flow cytometry using an anti-Pgp-PE antibody (Fig. 2b). Mean fluorescent intensities (MFI anti-Pgp minus MFI isotype control) were 2.67 in 697-R vs. 1.52 in 697 (N = 3). These results showed that, in addition to being upregulated in whole cell extracts, Pgp expression was also moderately elevated in silvestrol-resistant 697 cells relative to the parental cell line.

Fig. 2.

Pgp expression is elevated in 697-R cells. a Whole cell extracts from 697 and 697-R cells were immunoblotted for Pgp, using actin as a loading control. HL-60 cells without or with Pgp overexpression were included as negative and positive control, respectively. One of the three representative immunoblots is shown. b Live unfixed 697 and 697-R cells were incubated without antibody (black line), isotype control antibody (light gray line), or anti-Pgp-PE (medium gray line), washed, and examined by flow cytometry to determine surface Pgp expression. One of the three representative experiments is shown

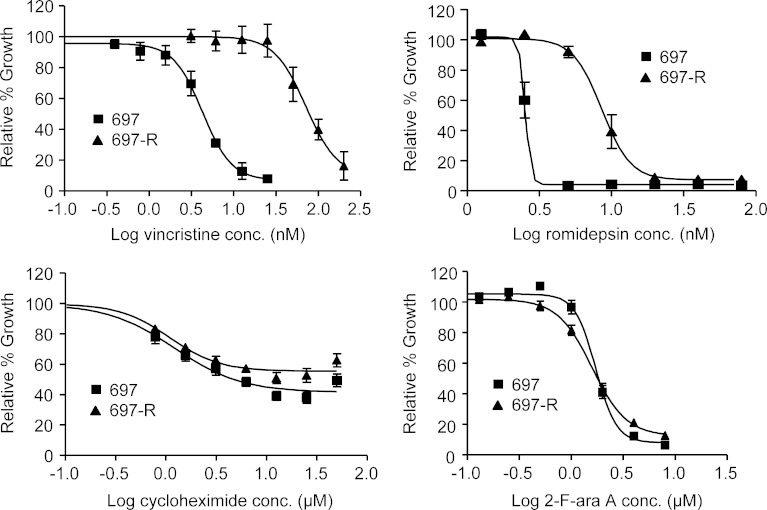

ABCB1/Pgp overexpression in cells can lead to cross-resistance to other Pgp substrates such as vincristine (23) and romidepsin (formerly depsipeptide; (24,25)). To determine if 697-R cells were selectively resistant to silvestrol, the cytotoxic effect of Pgp vs. non-Pgp substrates on 697-R cells was assessed by MTT assay. Based on our previous data, viability was determined at 48 h for cycloheximide, romidepsin, 2-F-ara-A (active metabolite of fludarabine), and vincristine and 72 h for silvestrol. As shown in Fig. 3, 697-R cells were significantly more resistant than 697 cells to Pgp substrates vincristine (IC50 = 4.3 nM for 697 and 72.1 nM for 697-R; p = 0.0012) and romidepsin (IC50 = 2.5 nM for 697 and 8.6 nM for 697-R; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between the parental and resistant cell lines in cytotoxicity of non-Pgp substrates cycloheximide and 2-F-ara-A.

Fig. 3.

697-R cells show increased resistance to Pgp substrates. 697 and 697-R cells (N = 3) were incubated with increasing concentrations of vincristine, romidepsin, cycloheximide, and 2-F-ara-A. Viability was determined by MTT assay at 48 h, and results were calculated relative to time-matched untreated cells

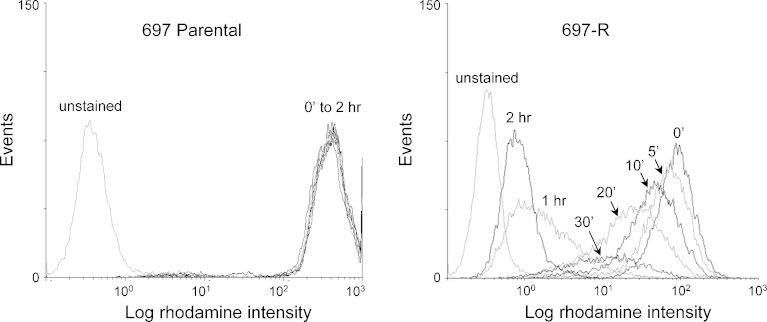

Pgp function was assessed in parental and resistant cell lines by an established rhodamine 123 efflux assay (19). Rhodamine 123 was completely retained in the parental 697 cells as expected, but was rapidly eliminated from 697-R cells (Fig. 4). As the majority of rhodamine 123 is eliminated from 697-R at 2 h, this timepoint was selected for the remaining studies.

Fig. 4.

Pgp function is elevated in 697-R cells. 697 parental (left) and 697-R cells (right) were incubated with rhodamine 123 for 30 min, washed, and assessed by flow cytometry immediately and at several times after washout. Unstained cells were included as a negative control. One of the three representative experiments is shown

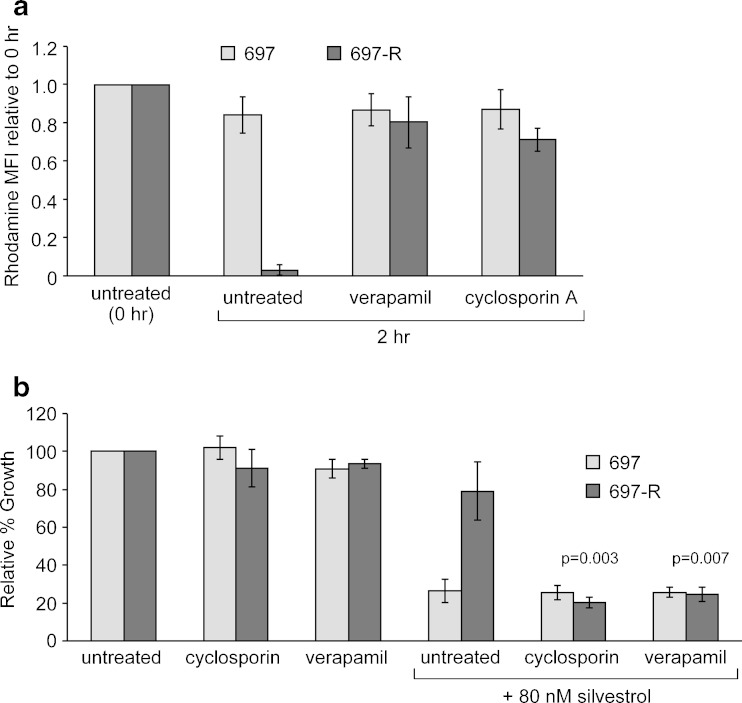

Pgp Inhibitors Block Pgp Function and Resensitize 697-R Cells to Silvestrol

To test if Pgp function in 697-R cells can be inhibited pharmacologically, rhodamine 123 efflux was measured in the presence of known Pgp inhibitors verapamil and cyclosporin A. As shown in Fig. 5a, both agents effectively blocked rhodamine 123 efflux from 697-R cells. To test if this inhibition resensitized the resistant cells to silvestrol, the viability of 697-R cells was measured using the MTT assay 48 h after treatment with combinations of verapamil or cyclosporin A and silvestrol. As seen in Fig. 5b, the combinations caused significantly more killing than can be explained by the addition of the effects of each treatment alone (p = 0.003 for cyclosporine A, p = 0.007 for verapamil), indicating that these agents were able to inhibit Pgp function and resensitize 697-R cells to silvestrol. The parental cells showed no significant interaction of silvestrol and the two Pgp inhibitors; in fact, the cytotoxicity of silvestrol in 697-R cells in combination with Pgp inhibitors was comparable to the cytotoxicity of silvestrol alone in the parental cells.

Fig. 5.

Pgp inhibitors prevent rhodamine 123 efflux and resensitize 697-R cells to silvestrol. a 697 and 697-R were incubated with rhodamine 123 for 30 min, washed, and re-incubated in media with no inhibitor, verapamil (10 μM), or cyclosporin A (1 μM) for 2 h. Cells were then examined by flow cytometry. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) for each cell line is shown normalized to the MFI immediately following washout. b 697 and 697-R cells were treated with verapamil (10 μM), cyclosporin A (1 μM), silvestrol (80 nM), or combination. Viability was determined by MTT assay 48 h after treatment. Results are shown relative to time-matched untreated cells (N = 3)

As Pgp substrates can also impede Pgp function, the impact of silvestrol on rhodamine 123 efflux in 697-R cells was also tested. No difference was observed in the rhodamine 123 efflux patterns in 697-R cells with or without silvestrol (data not shown). This suggests that unlike cyclosporin A, and verapamil, silvestrol does not function as a competitive inhibitor of rhodamine 123.

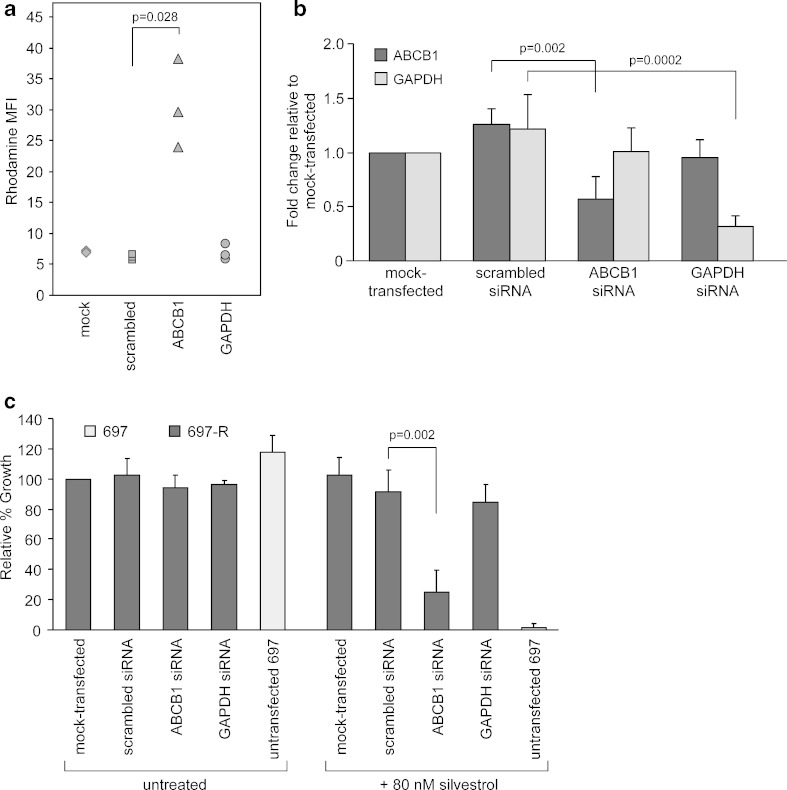

ABCB1 siRNA Specifically Blocks Pgp Function and Resensitizes 697-R Cells to Silvestrol

siRNA experiments were performed to determine the effect of specifically knocking down Pgp expression in 697-R cells. Cells were mock-transfected (no siRNA), transfected with nonsense scrambled siRNA, or transfected with siRNA directed to ABCB1 or GAPDH. Forty-eight hours after transfection, rhodamine 123 efflux assays showed that transfection with ABCB1 siRNA significantly inhibited the efflux of rhodamine 123 from 697-R cells compared to scrambled siRNA-transfected samples (Fig. 6a, mean MFI = 30.6 vs. 6.1; p = 0.028). To confirm that siRNA specifically reduced ABCB1 expression, real-time RT-PCR was performed on samples collected at the same timepoint. Results showed that ABCB1 expression is significantly decreased (more than twofold) with ABCB1 siRNA compared to scrambled siRNA control (Fig. 6b, p = 0.002). As a control, GAPDH expression, but not ABCB1 expression, was significantly reduced in samples transfected with GAPDH siRNA (p = 0.0002). To test if specific ABCB1 knockdown resensitized 697-R cells to silvestrol, transfected cells were incubated with silvestrol for 72 h and assessed by MTT assay. As seen in Fig. 6c, cells transfected with ABCB1 siRNA were significantly more sensitive to silvestrol compared to cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (p = 0.002).

Fig. 6.

ABCB1 siRNA specifically inhibits Pgp and resensitizes 697-R cells to silvestrol. 697-R cells were mock-transfected (no siRNA) or transfected with scrambled, ABCB1 or GAPDH siRNA (N = 3). Cells were incubated for 48 h. a Cells were analyzed for rhodamine 123 efflux. b ABCB1 expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR. Fold change of ABCB1 mRNA after mock, scrambled, ABCB1 or GAPDH siRNA transfection is normalized to the ABCB1 expression of mock-treated samples. GAPDH mRNA expression after transfections was measured as a positive control. c Transfected cells were incubated with 80 nM silvestrol for an additional 72 h, and growth inhibition was determined by MTT assay. Results are presented relative to mock-transfected 697-R cells without treatment. 697 parental cells incubated with corresponding drugs were included as a positive control

DISCUSSION

We and others have reported that silvestrol shows potent in vitro and in vivo activity in a variety of malignancies including ALL (8–13,26), but its mechanism(s) of resistance are unknown. ALL patients can develop resistance to available therapies due to tumor cell expression of ABC family members. Herein, we describe this as a mechanism of silvestrol resistance in vitro, using an established ALL cell line. In particular, we show that resistance to silvestrol is developed in 697 cells by upregulated ABCB1/Pgp and provide evidence that silvestrol is a Pgp substrate. As is observed with other Pgp substrates, silvestrol efficacy can be re-established using pharmacologic agents. For example, verapamil and cyclosporin A inhibit the efflux of the fluorescent Pgp substrate rhodamine 123 in Pgp-overexpressing cell lines (12,15,16). We show similar effects with these drugs in 697-R cells in conjunction with re-sensitization to silvestrol. However, additional work is needed to determine if this effect can be reproduced in vivo with pharmacologically obtainable concentrations of agents that have Pgp-inhibiting effects. Alternatively, our group is pursuing nanoparticle-mediated delivery of silvestrol that may evade Pgp-mediated protection in certain tumor types.

Interestingly, silvestrol as a substrate of Pgp was suggested by results from the NCI 60 cell line screen, in which silvestrol showed similarity to characterized Pgp substrates vinblastine, paclitaxel, and actinomycin-D, but not to cycloheximide. In validating these results, we observed that silvestrol has no direct effects either on tubulin polymerization or RNA synthesis (data not shown). This pattern of similarity between silvestrol and other Pgp substrates in the NCI screen was predicted by Lee et al. (27) and Alvarez et al. (28), who characterized Pgp expression in the 60 cell lines of this screen and used these data to generate a composite profile of a typical Pgp substrate compound.

Several shortcomings must be considered in the interpretation of this work, and important questions are raised as well. First, these findings were obtained using an ALL cell line, which may not adequately represent the disease. We therefore are working to confirm these results using primary ALL patient samples. However, obtaining tumor cells from ALL patients is challenging, as most patients are treated almost immediately upon diagnosis and also do not have circulating tumor cells; furthermore, primary ALL cells recover very poorly from cryopreservation and cell viability in culture is therefore quite limited. Regardless, it will be valuable to confirm these findings in additional cancer-relevant systems both in vitro and in vivo. Secondly, there are likely to be multiple mechanisms of silvestrol resistance and of drug efflux. The ABC transporters constitute a large family, and the pharmacologic inhibitors used in this work may not be specific to Pgp. To address this, we used gene-specific siRNA to confirm that Pgp is the primary cause of silvestrol resistance in 697-R cells compared to the parental 697 cell line. Additionally, microarray analysis showed no substantial differences in expression of any ABC family members other than ABCB1. Despite these two experiments, a minor role for other drug resistance-promoting proteins cannot be completely excluded.

We have not established the mechanism by which ABCB1 is upregulated in silvestrol-resistant cells. Interestingly, in the first generation of 697-R, we identified a single translocation, t(7;9)(q21.2;p13), that was not present in the parental line. This translocation occurs very near the chromosomal location of ABCB1 [7q21.1; (29)], and it is intriguing to hypothesize that this event is at least in part responsible for the dramatic increase in ABCB1 expression in 697-R. Newly sub-cloned 697 cells required nearly twice as long to develop the same level of silvestrol resistance, and the resulting resistant cell line lacked the 7q21.2 translocation. However, at this time, we have no direct evidence that this genetic alteration played a role in the upregulation of ABCB1. Pgp protein has also been shown to be upregulated by a wide variety of potentially interacting cellular signals including hypoxia (30); phosphoinositide-3 kinase/Akt, stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun, and NF-kB pathways (31,32), cell cycle inhibition/p27 upregulation (33), and others. Several of these pathways could be involved, as translation inhibition is likely to produce general cellular stress that activates these pathways. In agreement with this, we observe c-Jun induction in silvestrol-treated 697 cells (data not shown). Finally, several epigenetic mechanisms may contribute to increased ABCB1 expression (34,35), a possibility that is consistent with the relatively stable resistance phenotype we observe.

Following from this, our data present the possibility that silvestrol could, if dosed at low levels over time, induce its own resistance via direct or indirect upregulation of Pgp. It is important to note that an optimal schedule has not been defined for in vivo administration of silvestrol, so the relevance of our findings to silvestrol-mediated development of resistance in vivo is unknown. While this resistance could potentially be avoided by using higher doses administered less frequently, more information will be needed to determine if higher dosing is feasible or required for optimal efficacy. To date, in vivo experiments with silvestrol have been conducted using relatively low levels (0.2–0.5 mg/kg daily for 8 days (11,12) or 1.5 mg/kg three times weekly for 6 weeks (10)), which could be sufficiently low concentrations to allow surviving cells to develop resistance. We have worked to address these questions both in this report and the accompanying pharmacokinetics study (companion paper). Regardless, many diverse tumor types can exhibit increased Pgp expression either as a result of previous therapies or due to intrinsic tumor characteristics. Thus, the identification of elevated Pgp expression as a potential resistance mechanism is essential even if silvestrol is not the direct cause.

As a potential therapeutic agent, silvestrol is nearly unique in that its target within the cell is the initiation step of translation (11,12), the step at which most cellular regulation of translation occurs. Because of its potency and the uniqueness of its target, silvestrol is now under investigation and pre-clinical development at the National Cancer Institute. As part of this process, we recently completed a set of studies characterizing the in vitro metabolism and in vivo disposition of silvestrol in mice (companion paper). Our finding that silvestrol is a substrate of Pgp likely explains the poor oral absorption of silvestrol that we observe in mice. This is a crucial aspect of drug development that will be highly relevant to successful formulation and delivery of this novel agent. Finally, these data also suggest that silvestrol will have greater efficacy in diseases and in patients in which strong Pgp expression is either not observed or has not been linked to drug resistance, including subsets of ALL as well as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B cell malignancies (10).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Kapil Bhalla (University of Kansas Cancer Center), for providing the ABCB1-overexpressing HL60 cell line, and Dr. Charles Morrow (Wake Forest University School of Medicine) as well as the members of our laboratory for the many helpful comments. As to funding, silvestrol was provided through a National Cooperative Drug Discovery Group U19 [CA52956] and National Cancer Institute P01 [CA125066] to ADK. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [P01 CA081534 and P50 CA140158], The Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, and The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lazaris-Karatzas A, Montine KS, Sonenberg N. Malignant transformation by a eukaryotic initiation factor subunit that binds to mRNA 5′ cap. Nature. 1990;345(6275):544–547. doi: 10.1038/345544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenwald IB, Chen JJ, Wang S, Savas L, London IM, Pullman J. Upregulation of protein synthesis initiation factor eIF-4E is an early event during colon carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18(15):2507–2517. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmer SG, DeBenedetti A, Graff JR. Translational control of malignancy: the mRNA cap-binding protein, eIF-4E, as a central regulator of tumor formation, growth, invasion and metastasis. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(3A):1343–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane HA, Breuleux M. Optimal targeting of the mTORC1 kinase in human cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(2):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meric F, Hunt KK. Translation initiation in cancer: a novel target for therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(11):971–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowling RJ, Topisirovic I, Fonseca BD, Sonenberg N. Dissecting the role of mTOR: lessons from mTOR inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1804(3):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert F, Pelletier J. Translation initiation: a critical signalling node in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13(11):1279–1293. doi: 10.1517/14728220903241625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang BY, Su BN, Chai H, Mi Q, Kardono LB, Afriastini JJ, et al. Silvestrol and episilvestrol, potential anticancer rocaglate derivatives from Aglaia silvestris. J Org Chem. 2004;69(10):3350–3358. doi: 10.1021/jo040120f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S, Hwang BY, Su BN, Chai H, Mi Q, Kinghorn AD, et al. Silvestrol, a potential anticancer rocaglate derivative from Aglaia foveolata, induces apoptosis in LNCaP cells through the mitochondrial/apoptosome pathway without activation of executioner caspase-3 or -7. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(4B):2175–2183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas DM, Edwards RB, Lozanski G, West DA, Shin JD, Vargo MA, et al. The novel plant-derived agent silvestrol has B-cell selective activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113(19):4656–4666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-175430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bordeleau ME, Robert F, Gerard B, Lindqvist L, Chen SM, Wendel HG, et al. Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation modulates chemosensitivity in a mouse lymphoma model. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI34628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cencic R, Carrier M, Galicia-Vazquez G, Bordeleau ME, Sukarieh R, Bourdeau A, et al. Antitumor activity and mechanism of action of the cyclopenta[b]benzofuran, silvestrol. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4):e5223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cencic R, Carrier M, Trnkus A, Porco JA, Jr, Minden M, Pelletier J. Synergistic effect of inhibiting translation initiation in combination with cytotoxic agents in acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Leuk Res. 2010;34(4):535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swerts K, De Moerloose B, Dhooge C, Laureys G, Benoit Y, Philippe J. Prognostic significance of multidrug resistance-related proteins in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(3):295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami T, Takano M. Intestinal efflux transporters and drug absorption. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(7):923–939. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.7.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Findley HW, Jr, Cooper MD, Kim TH, Alvarado C, Ragab AH. Two new acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines with early B-cell phenotypes. Blood. 1982;60(6):1305–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins C, Kim CN, Fang G, Bhalla KN. Arsenic induces apoptosis of multidrug-resistant human myeloid leukemia cells that express Bcr-Abl or overexpress MDR, MRP, Bcl-2, or Bcl-x(L) Blood. 2000;95(3):1014–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aron JL, Parthun MR, Marcucci G, Kitada S, Mone AP, Davis ME, et al. Depsipeptide (FR901228) induces histone acetylation and inhibition of histone deacetylase in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells concurrent with activation of caspase 8-mediated apoptosis and down-regulation of c-FLIP protein. Blood. 2003;102(2):652–658. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynadie M, Matutes E, Catovsky D. Quantification of P-glycoprotein in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by flow cytometry. Leuk Res. 1997;21(9):825–831. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(97)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghetie MA, Ghetie V, Vitetta ES. Anti-CD19 antibodies inhibit the function of the P-gp pump in multidrug-resistant B lymphoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(12):3920–3927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain SR, Cheney CM, Johnson AJ, Lin TS, Grever MR, Caligiuri MA, et al. Mcl-1 is a relevant therapeutic target in acute and chronic lymphoid malignancies: down-regulation enhances rituximab-mediated apoptosis and complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(7):2144–2150. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khinkis LA, Levasseur L, Faessel H, Greco WR. Optimal design for estimating parameters of the 4-parameter hill model. Nonlinearity Biol Toxicol Med. 2003;1(3):363–377. doi: 10.1080/15401420390249925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horio M, Gottesman MM, Pastan I. ATP-dependent transport of vinblastine in vesicles from human multidrug-resistant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(10):3580–3584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao JJ, Foraker AB, Swaan PW, Liu S, Huang Y, Dai Z, et al. Efflux of depsipeptide FK228 (FR901228, NSC-630176) is mediated by P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313(1):268–276. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao JJ, Huang Y, Dai Z, Sadee W, Chen J, Liu S, et al. Chemoresistance to depsipeptide FK228 [(E)-(1S,4S,10S,21R)-7-[(Z)-ethylidene]-4,21-diisopropyl-2-oxa-12,13-dithi a-5,8,20,23-tetraazabicyclo(6–8)-tricos-16-ene-3,6,9,22-pentanone] is mediated by reversible MDR1 induction in human cancer cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314(1):467–475. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mi Q, Kim S, Hwang BY, Su BN, Chai H, Arbieva ZH, et al. Silvestrol regulates G2/M checkpoint genes independent of p53 activity. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(5A):3349–3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JS, Paull K, Alvarez M, Hose C, Monks A, Grever M, et al. Rhodamine efflux patterns predict P-glycoprotein substrates in the National Cancer Institute drug screen. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46(4):627–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez M, Paull K, Monks A, Hose C, Lee JS, Weinstein J, et al. Generation of a drug resistance profile by quantitation of mdr-1/P-glycoprotein in the cell lines of the National Cancer Institute Anticancer Drug Screen. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2205–2214. doi: 10.1172/JCI117910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Callen DF, Baker E, Simmers RN, Seshadri R, Roninson IB. Localization of the human multiple drug resistance gene, MDR1, to 7q21.1. Hum Genet. 1987;77(2):142–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00272381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wartenberg M, Fischer K, Hescheler J, Sauer H. Redox regulation of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance in multicellular prostate tumor spheroids. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(2):267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nwaozuzu OM, Sellers LA, Barrand MA. Signalling pathways influencing basal and H(2)O(2)-induced P-glycoprotein expression in endothelial cells derived from the blood–brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2003;87(4):1043–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thevenod F, Friedmann JM, Katsen AD, Hauser IA. Up-regulation of multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein via nuclear factor-kappaB activation protects kidney proximal tubule cells from cadmium- and reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(3):1887–1896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wartenberg M, Fischer K, Hescheler J, Sauer H. Modulation of intrinsic P-glycoprotein expression in multicellular prostate tumor spheroids by cell cycle inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1589(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker EK, El-Osta A. MDR1, chemotherapy and chromatin remodeling. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3(9):819–824. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.9.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kantharidis P, El-Osta A, deSilva M, Wall DM, Hu XF, Slater A, et al. Altered methylation of the human MDR1 promoter is associated with acquired multidrug resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(11):2025–2032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]