Abstract

Background

Primary intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a heterogeneous disease with regard to anatomic and histologic distribution. Thus, analyses focusing on primary intestinal NHL with large number of patients are warranted.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 581 patients from 16 hospitals in Korea for primary intestinal NHL in this retrospective analysis. We compared clinical features and treatment outcomes according to the anatomic site of involvement and histologic subtypes.

Results

B-cell lymphoma (n = 504, 86.7%) was more frequent than T-cell lymphoma (n = 77, 13.3%). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was the most common subtype (n = 386, 66.4%), and extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) was the second most common subtype (n = 61, 10.5%). B-cell lymphoma mainly presented as localized disease (Lugano stage I/II) while T-cell lymphomas involved multiple intestinal sites. Thus, T-cell lymphoma had more unfavourable characteristics such as advanced stage at diagnosis, and the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate was significantly lower than B-cell lymphoma (28% versus 71%, P < 0.001). B symptoms were relatively uncommon (20.7%), and bone marrow invasion was a rare event (7.4%). The ileocecal region was the most commonly involved site (39.8%), followed by the small (27.9%) and large intestines (21.5%). Patients underwent surgery showed better OS than patients did not (5-year OS rate 77% versus 57%, P < 0.001). However, this beneficial effect of surgery was only statistically significant in patients with B-cell lymphomas (P < 0.001) not in T-cell lymphomas (P = 0.460). The comparison of survival based on the anatomic site of involvement showed that ileocecal regions had a better 5-year overall survival rate (72%) than other sites in consistent with that ileocecal region had higher proportion of patients with DLBCL who underwent surgery. Age > 60 years, performance status ≥ 2, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase, Lugano stage IV, presence of B symptoms, and T-cell phenotype were independent prognostic factors for survival.

Conclusions

The survival of patients with ileocecal region involvement was better than that of patients with involvement at other sites, which might be related to histologic distribution, the proportion of tumor stage, and need for surgical resection.

Keywords: intestine, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, prognosis, histopathology

Background

The gastrointestinal tract is the most commonly involved extranodal location of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [1,2]. The intestines are the second most common site of involvement following the stomach, and account for 30 to 40% of primary gastrointestinal lymphomas [1-3]. However, information regarding primary intestinal NHL is relatively scarce because the majority of previous studies focused on gastric lymphoma [1,3,4]. The limited number of studies about primary intestinal NHL analyzed relatively small numbers of patients [5-12]. Another problem is that the classification of the pathology differs depending on the study period, as the majority of studies were retrospective analyses [1,4-6,9,13-15]. The use of old histologic classifications, such as the Kiel classification, makes comparisons among reported results difficult [1,5,6,9,11].

The ambiguity of anatomic classification is another obstacle to the analysis of primary intestinal NHL. Diseases involving the intestines are dichotomized into small and large intestinal diseases depending on the affected anatomic site. However, primary intestinal NHL most commonly involves the ileocecal region, probably due to the high proportion of lymphoid tissue [4,6,16]. Because the ileocecal region includes the area from the distal ileum to the cecum, it is often difficult to designate the ileocecal region as part of the small or large intestine. Thus, the designation for this region differs among studies, as some considered it part of the small or large intestine [1,9,10], and others distinguished it from the small and large intestine entirely [4,17]. Therefore, the estimated incidence rates of small and large intestinal lymphoma also varied among studies [4,17].

Due to this heterogeneity with regard to anatomic and histologic distribution of primary intestinal NHL, studies focusing on primary intestinal NHL in large patient samples using current pathologic classifications are warranted to understand this disease entity. Therefore, we analyzed data from Korean patients with primary intestinal NHL in the present multicenter retrospective study. We distinguished the ileocecal region from the small and large intestine for the purposes of classification. We analyzed the histologic distribution of primary intestinal NHL, and compared the clinical features and survival outcomes of patients.

Methods

Patients and tumor localization

Patients who presented with predominant intestinal lesions were defined as primary intestinal NHL according to the definition for primary gastrointestinal tract lymphoma proposed in previous reports [18,19]. Pathological diagnoses were made according to the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) classification or the World Health Organization (WHO) classification depending on the time of diagnosis. Cases with ambiguous histologic diagnosis or insufficient data regarding the pathology were excluded from this analysis. Tumor locations were determined using imaging findings, such as computerized tomography (CT), or surgical findings if surgical resection was performed. Small intestinal lymphomas were considered to be lymphomas between the duodenum and the ileum, while large intestinal lymphomas were considered to be lymphomas between the ascending colon and the rectum. The ileocecal region was defined as the area between the distal ileum to the cecum.

Clinical data

Investigators affiliated with the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) reviewed medical records and gathered clinical data for patients diagnosed with primary intestinal NHL between 1993 and 2010. Data included patient demographics and clinical features at diagnosis including stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), international prognostic index (IPI), histologic subtypes, the presence of B symptoms, and tumor location. Not all patients underwent colonoscopy for diagnosis because substantial number of patients underwent surgery to remove primary mass as diagnostic and therapeutic purpose. Thus, the specimen for pathologic diagnosis was obtained from biopsy under colonoscopy or surgically removed primary mass. Few patients underwent other specialized diagnostic techniques such as capsule endoscopy and double balloon endoscopy. All patients underwent imaging studies for staging work-up, including chest and abdomen-pelvis CT scans. The results of positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan were not included in this study because a limited number of patients underwent PET/CT scan for their staging work-up. Patients were staged according to the Lugano staging system for gastrointestinal lymphomas as previously reported [20,21]. Stage I is defined as disease confined to the intestine, stage II is defined as disease extending to local (II-1) or distant (II-2) nodes, stage II-E is defined as disease involving adjacent organs or tissues, and stage IV is defined as disseminated extranodal involvement or concomitant supradiaphragmatic lymph node involvement. The IPI risk was calculated from five parameters including age, performance status, serum LDH, number of extranodal involvement and Lugano stage. Clinical manifestation related with intestinal lesions such as intestinal obstruction, bleeding and perforation were analyzed because other symptoms were not specific to intestinal lesions. Data regarding treatments and outcomes include type of primary treatment, treatment response, and survival status. Response was defined according to WHO criteria [22]. The institutional review board of each participating center approved this retrospective analysis, which was a part of the larger CISL study registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT01043302).

Statistical analysis

The Fisher's exact test was applied to assess the association between categorical variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare mean values. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of the final follow-up or death from any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease progression, relapse, or death from any cause. Survival was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared by the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used in multivariate analyses to identify prognostic factors. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Primary site of involvement

We enrolled 581 patients from 16 hospitals in Korea for primary intestinal NHL in this retrospective analysis. 361 patients (62.1%) underwent colonoscopy for diagnostic purpose while 220 patients were diagnosed after surgery. Among patients undergoing colonoscopy, 334 patients were pathologically diagnosed as NHL whereas 27 patients were not diagnosed by colonoscopic biopsy. These 27 patients were diagnosed after surgical resection of primary intestinal mass. The majority of patients involved had single lesions in the intestines (89.2%). The ileocecal region was the most commonly involved site (n = 231, 39.8%, Table 1). Multiple intestinal involvement cases included the combined involvement of small and large intestines, and the involvement of two or more lesions within the small or large intestines (n = 63, 10.8%). Multiple intestinal involvements was significantly more frequent in T-cell lymphoma. The jejunal involvement was also more common in T-cell than B-cell lymphomas (15.6% versus 4.4%), thus, T-cell lymphomas showed more frequent involvement of the small intestine (P = 0.02). B-cell lymphomas accounted for the majority of ileocecal region lymphoma (n = 221, 95.7%).

Table 1.

Anatomic distribution of primary intestinal NHL

| Primary site | Total cases (n = 581) |

B-cell lymphoma (n = 504) |

T-cell lymphoma (n = 77) |

P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small intestine | ||||

| Duodenum | 31 (5.3) | 25 (5.0) | 6 (7.8) | 0.02 |

| Jejunum | 34 (5.9) | 22 (4.4) | 12 (15.6) | |

| Ileum | 97 (16.7) | 84 (16.7) | 13 (16.9) | |

| Ileocecal region | 231 (39.8) | 221 (43.8) | 10 (13.0) | < 0.001 |

| Large intestine | ||||

| Ascending/transverse colon | 87 (15.0) | 70 (13.9) | 17 (22.1) | 0.14 |

| Descending/sigmoid colon | 12 (2.1) | 11 (2.2) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Rectum | 26 (4.5) | 25 (5.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Multiple intestinal Involvement | 63 (10.8) | 46 (9.1) | 17 (22.1) | 0.002 |

NA: not applicable

*Fisher's exact test was used to assess the association between immunophenotype and the primary site in small and large intestine.

Characteristics of patients

The median age of the patients was 56 years (range: 15-92 years), and the male to female ratio was 1.71:1. Most patients had good performance status (≤ ECOG grade 0/1, 84.3%) and localized disease (Lugano stage I/II 71.1%). Thus, the IPI risks in our patients were mainly low or low intermediate (75.4%). B symptoms were relatively uncommon (20.7%), and bone marrow invasion was a rare event in primary intestinal NHL (7.4%, Table 2). Clinical presentations associated with intestinal obstruction such as intussusceptions were found in 96 patients (16.5%), and all these patients underwent emergent surgery. The frequency of bleeding (n = 13, 2.2%) and perforation (n = 25, 4.3%) was relatively lower than obstruction. Among the cases with perforation, 10 cases occurred during chemotherapy. When the characteristics of patients were compared according to the primary site of involvement, there were no significant differences. Only patients with multiple intestinal involvements were more likely to show high or high-intermediate IPI risk (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical features based on primary site of involvement

| Characteristics | Total cases (n = 581) |

Small intestine (n = 162) |

Ileocecal region (n = 231) |

Large intestine (n = 125) |

Multiple intestinal involvement (n = 63) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤ 60 | 356 (61.3) | 100 (61.7) | 146 (63.2) | 77 (61.6) | 33 (52.4) | 0.479 |

| > 60 | 225 (38.7) | 62 (38.3) | 85 (36.8) | 48 (38.4) | 30 (47.6) | ||

| Sex | Male | 367 (63.2) | 108 (66.7) | 146 (63.2) | 73 (58.4) | 40 (63.5) | 0.557 |

| Female | 214 (36.8) | 54 (33.3) | 85 (36.8) | 52 (41.6) | 23 (36.5) | ||

| Performance status | ECOG 0/1 | 490 (84.3) | 135 (83.9) | 197 (85.3) | 104 (83.2) | 54 (85.7) | 0.942 |

| ECOG ≥ 2 | 90 (15.5) | 26 (16.0) | 34 (14.7) | 21 (16.8) | 9 (14.3) | ||

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |||||

| Serum LDH level | Normal | 355 (61.1) | 92 (56.8) | 152 (65.8) | 77 (61.6) | 34 (54.0) | 0.086 |

| Increased | 210 (36.1) | 67 (41.4) | 71 (30.7) | 43 (34.4) | 29 (46.0) | ||

| Missing | 16 (2.8) | 3 (1.8) | 8 (3.5) | 5 (4.0) | |||

| B symptoms | Absent | 459 (79.0) | 125 (77.2) | 185 (80.1) | 103 (82.4) | 46 (73.0) | 0.441 |

| Present | 120 (20.7) | 36 (22.2) | 45 (19.5) | 22 (17.6) | 17 (27.0) | ||

| Missing | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | ||||

| Intestinal symptoms | Obstruction | 96 (16.5) | 25 (15.4) | 47 (20.3) | 14 (11.2) | 10 (15.9) | 0.267 |

| Bleeding | 13 (2.2) | 2 (1.2) | 8 (3.5) | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Perforation | 25 (4.3) | 8 (4.9) | 13 (5.6) | 3 (2.4) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Extranodal involvement | < 2 | 417 (71.8) | 105 (64.8) | 179 (77.5) | 103 (82.4) | 30 (47.6) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2 | 155 (26.7) | 55 (34.0) | 47 (20.3) | 21 (16.8) | 32 (50.8) | ||

| Missing | 9 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 5 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| IPI | L/LI | 277/151 (75.4) | 76/40 (71.6) | 129/48 (76.6) | 59/38 (77.6) | 13/25 (60.3) | < 0.001 |

| HI/H | 87/53 (22.4) | 24/20 (27.2) | 33/15 (20.8) | 16/8 (19.2) | 14/10 (38.1) | ||

| Missing | 13 (2.2) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (2.6) | 4 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Lugano stage | I/II | 139/264 (71.1) | 37/73 (67.9) | 54/126 (77.9) | 43/54 (77.6) | 5/21 (41.3) | < 0.001 |

| IV | 168 (28.9) | 52 (32.1) | 51 (22.1) | 28 (22.4) | 37 (58.7) | ||

| BM invasion | Absent | 494 (85.0) | 131 (80.9) | 199 (86.1) | 111 (88.8) | 53 (84.1) | 0.300 |

| Present | 43 (7.4) | 17 (10.5) | 13 (5.6) | 6 (4.8) | 7 (11.1) | ||

| ND | 44 (7.6) | 14 (8.6) | 19 (8.2) | 8 (6.4) | 3 (4.8) | ||

| Immunophenotype | B-cell | 504 (86.7) | 131 (80.9) | 221 (95.7) | 106 (84.8) | 46 (73.0) | < 0.001 |

| T-cell | 77 (13.3) | 31 (19.1) | 10 (4.3) | 19 (15.2) | 17 (27.0) |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; IPI: International Prognostic Index; L: low; LI: low-intermediate; HI: high-intermediate; H: high; BM: bone marrow; ND: not done

Histological distribution

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was the most common subtype (n = 386, 66.4%), and extranodal marginal zone B- cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) was the second most common subtype (n = 61, 10.5%). Burkitt lymphoma (BL, n = 31, 5.3%), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL, n = 19, 3.3%) and follicular lymphoma (FL, n = 7, 1.2%) together comprised only a minor fraction of intestinal NHL cases. The proportion of T-cell lymphomas was relatively small (n = 77, 13.3%) including three subtypes: peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified (PTCL-U, n = 34, 5.9%), enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL, n = 25, 4.3%) and extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (ENKTL, n = 18, 3.1%).

Comparison of histologic subtypes

The median age of MCL (60 years, Table 3) was the highest while BL, PTCL-U, and ENKTL had younger median ages (P = 0.002, Table 3). The majority of DLBCL and MALT cases presented as localized disease, while other subtypes more frequently presented as Lugano stage IV. The proportion of high/high-intermediate IPI risk patients was greater in the group with BL (Table 3). T-cell lymphoma showed more frequent occurrence of B symptoms (> 35%). The ileocecal region was the most common primary site of involvement in DLBCL. The large intestine was the most common primary site in MALT, thus, eleven cases of MALT occurred in the rectum (11/61, 18.0%). Multiple intestinal involvements such as multicentric involvement were more frequent in MCL (57.9%), and the pattern of intestinal involvement in MCL was peculiar. Thus, multi-centric involvement through entire colon like intestinal polyposis was frequently found in colonoscopy.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical features based on histological subtype

| Characteristics | DLBCL No. (%) |

MALT No. (%) |

BL No. (%) |

MCL No. (%) |

FL No. (%) |

PTCL-U No. (%) |

EATL No. (%) |

ENKTL No. (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 386 | 61 | 31 | 19 | 7 | 34 | 25 | 18 | |

| Median age (range) | 56 (15-92) | 55 (15-80) | 47 (15-78) | 60 (42-78) | 52 (39-81) | 49 (15-78) | 51 (23-75) | 47 (32-72) | 0.002 |

| Age > 60, % | 160 (41.5) | 22 (36.1) | 7 (22.6) | 10 (52.6) | 3 (42.9) | 11 (32.4) | 7 (28.0) | 5 (27.8) | 0.246 |

| Male, % | 240 (62.2) | 32 (52.5) | 25 (80.6) | 13 (68.4) | 4 (57.1) | 24 (70.6) | 17 (68.0) | 12 (66.7) | 0.273 |

| Performance status ≥ 2, % | 60 (15.6) | 6 (9.8) | 5 (16.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 9 (26.5) | 6 (24.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0.218 |

| Lugano stage IV, % | 94 (24.4) | 7 (11.5) | 17 (54.8) | 15 (78.9) | 3 (42.9) | 15 (44.1) | 8 (32.0) | 9 (50.0) | < 0.001 |

| Increased serum LDH, % | 150 (39.9) | 5 (8.5) | 23 (76.7) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (14.3) | 12 (36.4) | 8 (34.8) | 7 (38.9) | < 0.001 |

| Presence of B symptoms, % | 75 (19.5) | 7 (11.5) | 7 (22.6) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (14.3) | 12 (35.3) | 9 (36.0) | 6 (35.3) | 0.048 |

| Extranodal involvement ≥ 2, % | 93 (24.3) | 3 (5.4) | 18 (58.1) | 9 (47.4) | 2 (28.6) | 10 (29.4) | 10 (41.7) | 10 (55.6) | < 0.001 |

| IPI HI/H, % | 93 (24.5) | 5 (8.9) | 15 (48.4) | 7 (36.8) | 1 (14.3) | 9 (26.5) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (22.2) | 0.008 |

| Bone marrow invasion, % | 20 (5.2) | 4 (6.6) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (26.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.8) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal obstruction, % | 69 (17.8) | 7 (11.5) | 6 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.5) | 4 (11.8) | 4 (16.0) | 4 (22.2) | 0.398 |

| Bleeding, % | 8 (2.0) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.964 |

| Perforation, % | 19 (4.9) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.194 |

| Small intestine, % | 104 (26.9) | 14 (23.0) | 11 (35.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 13 (38.2) | 10 (40.0) | 8 (44.4) | < 0.001 |

| Ileocecal region, % | 187 (48.4) | 19 (31.1) | 9 (29.0) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (42.9) | 7 (20.6) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Large intestine, % | 73 (18.9) | 21 (34.4) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (14.7) | 10 (40.0) | 4 (22.2) | < 0.001 |

| Multiple intestinal lesions, % | 22 (5.7) | 7 (11.5) | 6 (19.4) | 11 (57.9) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (26.5) | 3 (12.0) | 5 (27.8) | < 0.001 |

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; IPI: International Prognostic Index; HI: high-intermediate; H: high; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MALT: extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma; BL: Burkitt lymphoma; PTCL-U: peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified; EATL: enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; MCL: mantle cell lymphoma; ENKTL: extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma; FL: follicular lymphoma

Treatments and outcomes

Chemotherapy was the predominant treatment in patients with primary intestinal NHL regardless of the involved site. Thus, the majority of patients received chemotherapy as a curative treatment (n = 521, 89.7%, Table 4). Various chemotherapy regimens were used, although CHOP or rituximab-CHOP was the main regimen for lymphoma, therefore, comparisons of outcomes based on chemotherapy regimens were not performed. Surgical resection was performed in 289 patients (49.7%) for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes as mentioned earlier. Among patients diagnosed by colonoscopy, some patients underwent surgery to remove primary mass of intestine. The ileocecal region was the most common site of surgery (64.1%). Radiotherapy was used less frequently than chemotherapy and surgery. However, radiotherapy was used frequently in patients with MALT (n = 13, 21.3%) compared to other subtypes, while approximately half of all patients with MALT received chemotherapy due to indolent clinical courses (n = 30, 49.2%, Table 5). The overall response rates of DLBCL, BL and MCL were greater than 80% while PTCL-U, EATL and ENKTL showed around 50% of the overall response rate. Consistent with these findings, the proportion of relapse or progression was higher in PTCL-U, EATL and ENKTL, and this fact lead to a higher number of deaths than in B-cell subtypes. Among B-cell lymphomas, relapse or progression was more frequent in MCL and FL, even though they showed a relatively high overall response rate.

Table 4.

Comparison of treatments and outcomes based on primary site

| Characteristics | Total cases (n = 581) |

Small intestine (n = 162) |

Ileocecal region (n = 231) |

Large intestine (n = 125) |

Multiple intestinal involvement (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment* | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 521 (89.7%) | 143 (88.3%) | 213 (92.2%) | 105 (84.0%) | 60 (95.2%) |

| Surgical resection | 289 (49.7%) | 74 (45.7%) | 148 (64.1%) | 49 (39.2%) | 18 (28.6%) |

| Radiotherapy | 56 (9.6%) | 21 (13.0%) | 18 (7.8%) | 13 (10.4%) | 4 (6.3%) |

| Response | |||||

| Complete response | 360 (62.0%) | 94 (58.0%) | 164 (71.0%) | 71 (57.0%) | 31 (49.0%) |

| Partial response | 62 (10.7%) | 16 (9.9%) | 16 (6.9%) | 19 (15.0%) | 11 (18.0%) |

| Outcome | |||||

| Relapse or Progression | 199 (34.3%) | 57 (35.2%) | 65 (28.1%) | 50 (40.0%) | 27 (42.9%) |

| Dead | 152 (26.2%) | 44 (27.2%) | 47 (20.3%) | 36 (28.8%) | 25 (39.7%) |

| Survival | |||||

| Median OS | Not reached | Not reached | Not reached | 140 months | 61 months |

| 5-year OS | 67% | 65% | 72% | 67% | 55% |

| Median PFS | 88 months | 55 months | 115 months | 66 months | 28 months |

| 5-year PFS | 53% | 50% | 62% | 50% | 37% |

*Some patients were treated with combined modality such as surgery plus chemotherapy. Thus, the sum of number of each treatment is larger than total number of patients.

Table 5.

Comparison of treatments and outcomes based on histologic subtypes

| Characteristics | DLBCL No. (%) |

MALT No. (%) |

BL No. (%) |

MCL No. (%) |

FL No. (%) |

PTCL-U No. (%) |

EATL No. (%) |

ENKTL No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment* | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 368 (95.3) | 30 (49.2) | 29 (93.5) | 19 (100.0) | 5 (71.4) | 30 (88.2) | 23 (92.0) | 17 (94.4) |

| Surgical resection | 223 (57.8) | 25 (41.0) | 9 (29.0) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (42.9) | 9 (26.5) | 12 (48.0) | 7 (38.9) |

| Radiotherapy | 32 (8.3) | 13 (21.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (11.8) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (5.6) |

| Response | ||||||||

| Complete response | 264 (68.4) | 36 (59.0) | 22 (71.0) | 11 (57.9) | 4 (57.1) | 11 (32.4) | 7 (28.0) | 5 (27.8) |

| Partial response | 36 (9.3) | 5 (8.2) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (26.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.8) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (16.7) |

| Outcome | ||||||||

| Relapse or Progression | 112 (29.0) | 14 (23.0) | 11 (35.5) | 8 (42.1) | 4 (57.1) | 19 (55.9) | 18 (72.0) | 13 (73.2) |

| Dead | 87 (22.5) | 8 (13.1) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (28.6) | 18 (52.9) | 15 (60.0) | 9 (50.0) |

| Survival | ||||||||

| Median OS | Not reached | Not reached | Not reached | 46 months | 54 months | 35 months | 8.6 months | 7 months |

| 5-year OS | 72% | 88% | 76% | 39% | 42% | 23% | 35% | 45% |

| Median PFS | Not reached | 115 months | Not reached | 31 months | 16 months | 10 months | 4.2 months | 4 months |

| 5-year PFS | 58% | 80% | 60% | 0% | 22% | 17% | 23% | 21% |

*Some patients were treated with combined modality such as surgery plus chemotherapy. Thus, the sum of number of each treatment is larger than total number of patients.

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MALT: extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma; BL: Burkitt lymphoma; PTCL-U: peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified; EATL: enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; MCL: mantle cell lymphoma; ENKTL: extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma; FL: follicular lymphoma

Survival and prognostic factors

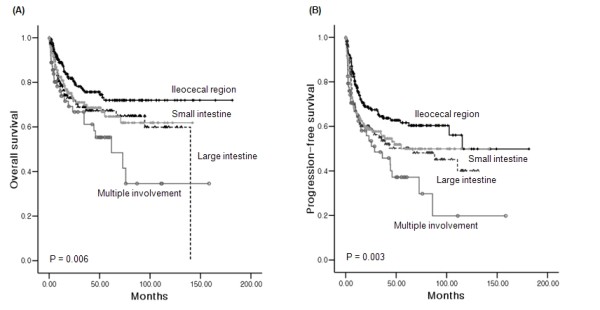

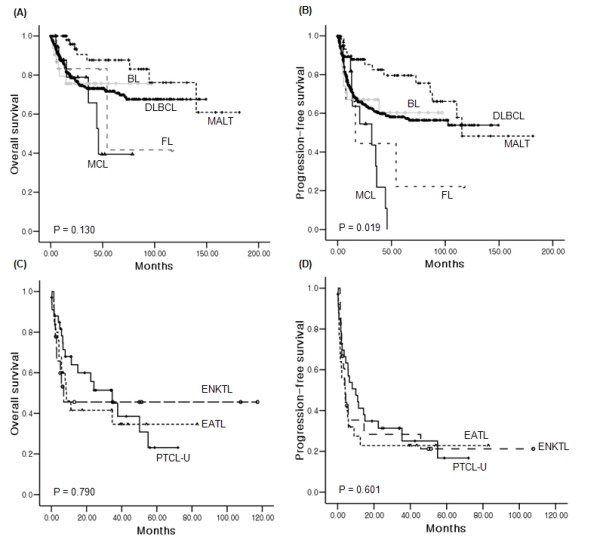

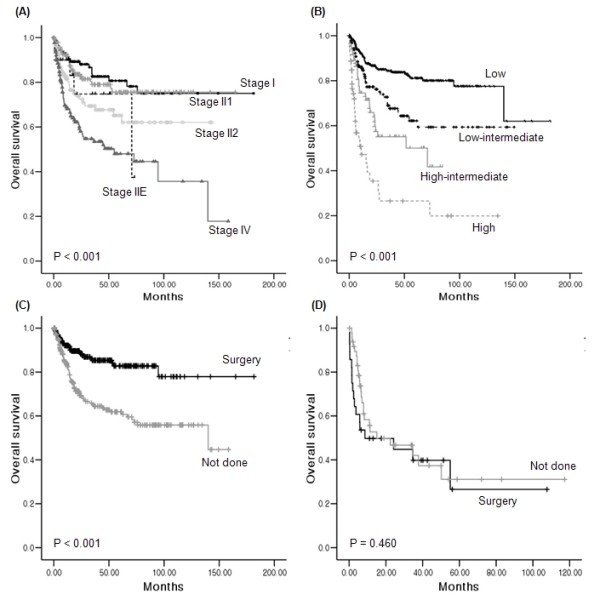

The 5-year OS and PFS rates of ileocecal NHL were 72% and 62%, respectively, while the small and large intestines showed similar survival rates (Figure 1). The 5-year OS rate of B-cell lymphoma was significantly better than that of T-cell lymphoma (71% versus 28%, P < 0.001). The comparison of OS in all subtypes of B-cell lymphoma did not show a significant difference (Figure 2A, P = 0.130). However, when the OS of MALT was compared with that of DLBCL and MCL, the OS of MALT was significantly better than DLBCL and MCL (P = 0.021 and 0.001, respectively). There were no significant differences of OS among PTCL-U, EATL, and ENKTL, although the median OS (34.3 months) of PTCL-U was longer than that of ENKTL (8.6 months) and EATL (7.0 months, Figure 2B). The PFS of MCL and FL was shorter than other subtypes of B-cell NHL (Figure 2C). However, the PFS of three T-cell subtypes showed similar outcomes (Figure 2D). Patients with Lugano stage II2 and IV disease had significantly worse OS than stage I and II1 (Figure 3A). Other parameters affecting the IPI score, such as age, ECOG performance status, serum LDH, and the number of extranodal involvements were also significantly associated with OS (data not shown). Thus, the IPI showed a clear association with OS (P < 0.001, Figure 3B). Patients who underwent surgical resection had better OS than patients who did not undergo surgery (5-year OS rate 77% versus 57%, P < 0.001). However, the survival benefit associated with surgical resection was significant only in B-cell lymphomas and not in T-cell lymphomas (Figure 3C, D). Multivariate analyses with these parameters for OS showed that age > 60 years, poor performance status, elevated serum LDH, Lugano stage IV, presence of B symptoms, and T-cell phenotype were independent predictive indicators for poor OS (Table 6).

Figure 1.

Comparison of survival curves based on the site of involvement. (A, B) Overall and progression-free survival curves according to primary site of involvement. Patients with ileocecal region involvement had better survival outcomes than patients with involvement of the small and large intestines. The outcomes of patients with multiple intestinal involvement were significantly worse (P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Comparison of survival curves based on the histologic subtypes. (A, B) Overall and progression-free survival curves according to subtype of B-cell lymphoma. MALT lymphoma showed better OS than other subtypes, while BL and DLBCL showed similar OS curves to each other. (C, D) Overall and progression-free survival curves according to subtype of T-cell lymphoma. There were no significant differences among PTCL-U, EATL, and ENKTL.

Figure 3.

Comparison of survival curves based on the clinical characteristics. (A) Lugano stage II2 and IV cases had significantly worse OS, while there were no significant differences in OS between stage I and II1. (B) IPI was significantly associated with OS. (C) In B-cell lymphoma, patients who underwent surgical resectioning had better OS than patients that did not. (D) Surgical resections failed to lead to survival differences in T-cell lymphoma.

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors

| Characteristics | P value | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| Age > 60 | < 0.001 | 1.945 | 1.379 | 2.743 |

| Performance status ≥ 2 | < 0.001 | 2.072 | 1.384 | 3.101 |

| Elevated serum LDH | 0.002 | 1.776 | 1.233 | 2.558 |

| Extranodal involvement ≥ 2 | 0.579 | 0.892 | 0.596 | 1.335 |

| Lugano stage IV | 0.001 | 1.248 | 1.090 | 1.429 |

| Multiple intestinal involvement | 0.357 | 1.076 | 0.920 | 1.259 |

| Immunophenotype T-cell | < 0.001 | 3.645 | 2.454 | 5.416 |

| B symptoms | 0.028 | 1.530 | 1.046 | 2.237 |

| Surgical resection not done | 0.281 | 1.235 | 0.842 | 1.811 |

Discussion

Primary intestinal NHL accounts for a major proportion of cases of extranodal lymphoma. Although its prognosis is poor compared to gastric lymphoma, there are few studies analyzing the clinical features and survival outcomes of primary intestinal NHL according to primary site of involvement and histologic subtype. In this study, we analyzed data for 581 patients, making ours the largest sample among studies investigating primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. The clinical features of our study were similar to those described in previous studies, and revealed that primary intestinal NHL occurs more frequently in male patients and predominantly presents as a localized disease (Table 7).

Table 7.

Summary of published results of prospective and retrospective studies

| References | Study type | Time period | Nationality | number | Location | M/F | B/T cell | Stage I/II vs. III/IV | B-cell | T-cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d'Amore et al [1] | Retrospective | 1983-1991 | Denmark | 109 | SI/LI | 76/33 | 93/16 | 56 vs. 48 | High grade (51) | PTCL (10) |

| Intermediate grade (18) | ALCL (6) | |||||||||

| Unknown (3) | Low grade (21) | |||||||||

| Koch et al [4] | Retrospective | 1992-1996 | Germany | 58 | SI/LI | 40/18 | 48/10 | 52 vs. 6 | High grade (39) | T-cell (10) |

| Low grade (4) | ||||||||||

| BL/LBL (5) | ||||||||||

| Kohno et al [6] | Retrospective | 1981-2000 | Japan | 143 | SI/LI | 109/34 | 122/21 | Not described | Large cell (84), BL (16) | PTCL (15) |

| MALT (10), MCL (7) | ENKTL (2) | |||||||||

| FL (4) | ALCL (2) | |||||||||

| Daum et al [16] | Prospective | 1995-1999 | Germany | 56 | SI/LI | 25/31 | 21/35 | 42 vs. 14 | DLBCL (18) | EATL (28) |

| MALT (2), FL (1) | Unknown (7) | |||||||||

| Yin et al [12] | Retrospective | 1996-2005 | China | 34 | SI | 22/12 | 27/7 | 22 vs. 12 | DLBCL (24) | Unknown (7) |

| MALT (3) | ||||||||||

| Kako et al [10] | Retrospective | 1990-2007 | Japan | 23 | SI | 16/7 | 20/3 | 11 vs. 12 | DLBCL (15), FL (1) | EATL (2) |

| MCL (1), MALT (2) | ALCL (1) | |||||||||

| Unknown (1) | ||||||||||

| Li et al [9] | Retrospective | 1992-2003 | China | 40 | SI/LI | 26/14 | 38/2 | 28 vs. 12 | DLBCL (17) | PTCL (1) |

| MALT (20) | Unknown (1) | |||||||||

| Unknown (1) | ||||||||||

| Wong et al [8] | Retrospective | 1989-1999 | Singapore | 14 | LI | 13/1 | 14/0 | 5 vs. 9 | DLBCL (8), MCL (4) | |

| BL (2) |

SI: small intestine; LI: large intestine; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MALT: extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma; BL: Burkitt lymphoma; PTCL-U: peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified; EATL: enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; MCL: mantle cell lymphoma; ENKTL: extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma; FL: follicular lymphoma; LBL: lymphoblastic lymphoma

The incidence of B-cell lymphoma was much that of higher than T-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL was the main subtype. This is consistent with the observation that the majority of gastrointestinal tract NHL is of B-cell origin, including DLBCL and MALT lymphoma [2,3,8,23]. However, the proportion of DLBCL (n = 386, 66.4%) was significantly higher than MALT (n = 64, 10.6%) in our study. This is different from gastric lymphoma, in which MALT lymphoma accounts for approximately 40% of all cases [15,23]. This high frequency of DLBCL might be associated with the worse prognosis of intestinal lymphoma compared to gastric lymphoma [1,3,15,24]. The relatively higher incidence of T-cell lymphoma may be another cause of the poor prognosis for intestinal NHL. Our study showed the occurrence of three subtypes of T-cell lymphoma including PTCL-U, EATL and ENKTL with a frequency of 13.2%. Although the proportion of T-cell lymphomas varied according to the type of study and number of patients [5,9,16], our proportion was comparable to previous studies with a relatively large number of patients [1,3,4]. Patients with T-cell lymphomas more frequently presented with advanced disease and constitutional B symptoms, and their overall response rate to treatment was inferior to that of B-cell lymphomas. This resulted in significantly worse survival outcomes for T-cell lymphoma compared to B-cell lymphoma in our study, which is consistent with previous results [7,16]. The comparison of survival outcomes based on subtypes of NHL demonstrated that MCL did not show a survival curve plateau. This reflects MCL has higher risk of relapse resulting in worse OS and PFS than other subtypes (Figure 2) in consistent with previous results [25-27]. The 5-year OS of PTCL-U in our study was inferior to previously reported 5-year OS of nodal PTCL-U, suggesting a poor prognosis for intestinal T-cell lymphoma [28].

The ileocecal region was the most common site of involvement, accounting for approximately 40% of primary sites in this study (Table 1). However, this region was mainly affected by B-cell lymphomas (95.7%). The frequent occurrence of B-cell lymphomas in the ileocecal region was associated with high proportions of DLBCL (Table 2). T-cell lymphomas were extremely rare in the ileocecal region (4.3%), while involvement of the jejunum was more common in T-cell lymphomas (12.5%) than in B-cell (3.6%). This relatively high incidence of T-cell lymphomas in the small intestine, especially the jejunum, was also noted in previous studies [3,4,6]. Like previous studies reporting high proportions of MALT lymphoma in the duodenum and rectum in East Asian samples [6], the high proportion of B-cell lymphoma in the duodenum and rectum in this study was also associated with frequent occurrence of MALT lymphoma.

A comparison of survival outcomes based on primary site of involvement revealed that involvement of the ileocecal region was associated with better survival rates than involvement of the small and large intestine. Patients with multiple intestinal involvements had the worst survival outcomes. A previous study reported that the overall survival of ileocecal lymphoma was similar to that of gastric lymphoma and superior to that of small intestinal lymphoma [4]. There are several possible explanations for the superior survival outcomes of patients with involvement in the ileocecal region. First, T-cell lymphoma rarely occurs in the ileocecal region compared to the small and large intestine. Thus, the proportion of T-cell lymphoma in our study (4.3%) was similar to that of a previous study reporting 4% in the ileocecal region [4]. Second, lymphomas in the ileocecal region often presented with complications, such as obstructions requiring surgical intervention. Thus, more than 50% of patients with lymphoma in the ileocecal region underwent immediate surgery [1,4,17,29,30]. Our study also showed that the percentage of patients who underwent surgery in the ileocecal region (64.1%) was significantly higher than the percentage of patients who required surgery in the small and large intestines (45.7% and 39.2%, respectively, Table 4). Previous studies reported that primary surgical treatment had a favourable influence on the prognosis of intestinal lymphoma, especially for localized disease [7,31]. Thus, the fact that many of our patients received surgery might explain the better survival of patients with ileocecal lymphoma in our study as compared to other studies.

The optimal treatment strategy for intestinal lymphoma is still unclear. Although conservative treatment is preferred to surgery in localized gastric lymphomas, the same is not true for intestinal lymphomas because surgery in combination with chemotherapy has proven superior to any other treatment combination [1,5]. In a previous study, we compared the outcomes of surgery followed by chemotherapy, and chemotherapy alone in intestinal DLBCL, and found that surgery followed by chemotherapy led to better survival outcomes [32]. Consistent with these findings, surgical resection was associated with survival benefits in patients with B-cell lymphoma in the present study (P < 0.001, Figure 3C). Considering the fact that more than 90% of patients received chemotherapy, this result may be interpreted to reflect a survival advantage of surgery plus chemotherapy. However, the survival benefit was not observed in patients with T-cell lymphoma (P = 0.460, Figure 3D), possibly due to the high proportion of Lugano stage IV cases in our sample. Thus, need for surgery failed to show independent prognostic value in the multivariate analysis for OS (Table 6). The results of our multivariate analysis demonstrated that age, performance status, serum LDH, Lugano stage, B symptoms, and T-cell immunophenotype were all independently prognostic for OS in patients with intestinal NHL.

Although this is the largest series of primary intestinal NHL, our study has some limitations. First, patients included in this analysis were not consecutively diagnosed because of its retrospective study in nature. Second, we could not provide the results of PET/CT scan because PET/CT scan was not widely used before 2006 in Korea.

Conclusions

In summary, we determined clinical features and outcomes of patients with primary intestinal NHL. The survival of patients with ileocecal region involvement was better than that of patients with involvement at other sites, which might be related to histologic distribution, the proportion of tumor stage, and need for surgical resection. Factors associated with the IPI score and T-cell immunophenotype were shown to be prognostic in this disease entity. Surgical resection may provide survival benefits to patients with localized B-cell intestinal NHL.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SJK participated in the design of the study and review of clinical data, and drafted the manuscript. HJK, JSK, SYO, CWC, SIL, KWP, JHW, MKK, JHK, YCM, JYK, JMK, IGH, HJK, JP, and SO recorded the clinical data. CS and WSK participated in the coordination of the study, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Seok Jin Kim, Email: kstwoh@skku.edu.

Chul Won Choi, Email: bonnie@korea.ac.kr.

Yeung-Chul Mun, Email: yeungchul@ewha.ac.kr.

Sung Yong Oh, Email: drosy@dau.ac.kr.

Hye Jin Kang, Email: hyejin@kcch.re.kr.

Soon Il Lee, Email: avnrt@hanmail.net.

Jong Ho Won, Email: jhwon@hosp.sch.ac.kr.

Min Kyoung Kim, Email: kmk21c@med.yu.ac.kr.

Jung Hye Kwon, Email: dazzlingston@chol.com.

Jin Seok Kim, Email: hemakim@yuhs.ac.

Jae-Yong Kwak, Email: jykwak@chonbuk.ac.kr.

Jung Mi Kwon, Email: asever-kjm@hanmail.net.

In Gyu Hwang, Email: higyu72@yahoo.co.kr.

Hyo Jung Kim, Email: hemonc@paran.com.

Jae Hoon Lee, Email: jhlee@gilhospital.com.

Sukjoong Oh, Email: sukjoong.oh@samsung.com.

Keon Woo Park, Email: pkw800041@naver.com.

Cheolwon Suh, Email: csuh@amc.seoul.kr.

Won Seog Kim, Email: wskimsmc@skku.edu.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Samsung Biomedical Research Institute Grant (#SBRI C-B0-211-1) and the IN-SUNG Foundation for Medical Research (CA98661).

References

- d'Amore F, Brincker H, Gronbaek K, Thorling K, Pedersen M, Jensen MK, Andersen E, Pedersen NT, Mortensen LS. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(8):1673–1684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.8.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko YH, Kim CW, Park CS, Jang HK, Lee SS, Kim SH, Ree HJ, Lee JD, Kim SW, Huh JR. REAL classification of malignant lymphomas in the Republic of Korea: incidence of recently recognized entities and changes in clinicopathologic features. Hematolymphoreticular Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists. Revised European-American lymphoma. Cancer. 1998;83(4):806–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer. 2003;97(10):2462–2473. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18):3861–3873. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Pagliani G, Bendandi M, Gherlinzoni F, Merla E, Salvucci M, Tura S. Primary intestinal lymphoma: clinical and therapeutic features of 32 patients. Haematologica. 1997;82(3):305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno S, Ohshima K, Yoneda S, Kodama T, Shirakusa T, Kikuchi M. Clinicopathological analysis of 143 primary malignant lymphomas in the small and large intestines based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology. 2003;43(2):135–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim WS, Kim K, Ko YH, Kim JJ, Kim YH, Chun HK, Lee WY, Park JO, Jung CW. et al. Intestinal lymphoma: exploration of the prognostic factors and the optimal treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(2):339–344. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001593111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(7):586–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Shi YK, He XH, Zou SM, Zhou SY, Dong M, Yang JL, Liu P, Xue LY. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the small and large intestine: clinicopathological characteristics and management of 40 patients. Int J Hematol. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kako S, Oshima K, Sato M, Terasako K, Okuda S, Nakasone H, Yamazaki R, Tanaka Y, Tanihara A, Kawamura Y, Clinical outcome in patients with small intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009. pp. 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim YH, Lee JH, Yang SK, Kim TI, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Kim JI, Kim SW, Kim JO, Jung IK. et al. Primary colon lymphoma in Korea: a KASID (Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases) Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(12):2243–2247. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Chen CQ, Peng CH, Chen GM, Zhou HJ, Han BS, Li HW. Primary small-bowel non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a study of clinical features, pathology, management and prognosis. J Int Med Res. 2007;35(3):406–415. doi: 10.1177/147323000703500316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer MH, el-Akkad S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults: clinical features and management of 300 cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(4):846–858. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domizio P, Owen RA, Shepherd NA, Talbot IC, Norton AJ. Primary lymphoma of the small intestine. A clinicopathological study of 119 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(5):429–442. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma--results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18):3874–3883. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, Dederke B, Foss HD, Stein H, Thiel E, Zeitz M, Riecken EO. Intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on Intestinal non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2740–2746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney KA, Cartwright RA, Gilman EA. Descriptive epidemiology of gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(11-12):1929–1934. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin KJ, Ranchod M, Dorfman RF. Lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 117 cases presenting with gastrointestinal disease. Cancer. 1978;42(2):693–707. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197808)42:2<693::AID-CNCR2820420241>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson PG. Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 1994;25(10):1020–1029. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatiner A, d'Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, Lister TA, Norton A, Salem P, Shipp M. et al. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5(5):397–400. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo S, Rossi A, Oldani E, Motta T, Giardini R, Zinzani PL, Zucca E, Gomez H, Ferreri AJ, Pinotti G. et al. The modified International Prognostic Index can predict the outcome of localized primary intestinal lymphoma of both extranodal marginal zone B-cell and diffuse large B-cell histologies. Br J Haematol. 2002;118(1):218–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47(1):207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::AID-CNCR2820470134>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch P, Probst A, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Liersch R, del Valle F, Clasen H, Hirt C. et al. Treatment results in localized primary gastric lymphoma: data of patients registered within the German multicenter study (GIT NHL 02/96) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7050–7059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Takeshita M, Kurahara K, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. A clinicopathologic study of primary small intestine lymphoma: prognostic significance of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-derived lymphoma. Cancer. 2000;88(2):286–294. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<286::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucca E, Roggero E, Pinotti G, Pedrinis E, Cappella C, Venco A, Cavalli F. Patterns of survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(3):257–262. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinotti G, Zucca E, Roggero E, Pascarella A, Bertoni F, Savio A, Savio E, Capella C, Pedrinis E, Saletti P. et al. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in a series of 93 patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26(5-6):527–537. doi: 10.3109/10428199709050889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, Cortelazzo S, Motta T, Gospodarowicz MK, Patterson BJ, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Devizzi L. et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101(7):2489–2495. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen R, Schmidt WP, Muller-Hermelink HK, Schmitz N. The International Prognostic Index determines the outcome of patients with nodal mature T-cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(3):366–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Aegerter P, Delmer A, Brousse N, Galian A, Rambaud JC. Primary digestive tract lymphoma: a prospective multicentric study of 91 patients. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Digestifs. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(6):1662–1671. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91061-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turowski GA, Basson MD. Primary malignant lymphoma of the intestine. Am J Surg. 1995;169(4):433–441. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim WS, Kim K, Ahn JS, Jung CW, Lim HY, Kang WK, Park K, Ko YH, Kim YH. et al. Prospective clinical study of surgical resection followed by CHOP in localized intestinal diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2007;31(3):359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Kang HJ, Kim JS, Oh SY, Choi CW, Lee SI, Won JH, Kim MK, Kwon JH, Mun YC. et al. Comparison of treatment strategies for patients with intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: surgical resection followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Blood. 2011;117(6):1958–1965. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]