Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether a web-based health and leadership development program—designed specifically for managers—was associated with changes in self-reported and biometric indicators of cardiovascular risk (CVD) within the context of a randomized control trial.

Methods

145 managers from eight organizations participated in a 6-month Internet-based program or a control condition. They completed pre- and posttest assessments that included both self-reported attitudes (on diet, exercise, and mental health) and biometric measures (e.g., body weight, waist circumference).

Results

The intervention was associated with improvements in dietary attitudes, dietary self-efficacy, and exercise, and reductions in distress symptoms. Women in the program reduced their waist circumference significantly more than controls.

Conclusions

The program showed promise for reducing CVD risk factors. Similar results across diverse organizations suggest the program may be useful across industry types.

Managers and executive personnel face risks for cardiovascular disease (CVD). For example, a multi-year survey of Canadian public executives found 20% had cardiovascular illness and over 50% were overweight or obese (1). Managers also perceive themselves to have high risk for CVD, citing stressors like work overload, time pressures, long working hours, work-related travel (2, 3). Indeed, research suggests CVD risks include long working hours (4, 5), business travel (6, 7) and high job demands (8). In turn, these pressures can lead to ignoring health concerns and leaving health problems untreated. Overall, research suggests a need for prevention programs for this occupational group (9, 10).

Many work-related studies find high rates of CVD in lower-level occupational groups. Consequently, prevention efforts often target lower income and non-managerial occupations (11, 12). However, the relationship between occupational level and health is complex (13, 14). All workers, regardless of job status, may experience risk factors such as low social support (15), hostility (16), sedentary lifestyle, and limited skill discretion or job control at work (17, 18).

Further, organizational connections between managers and employees mean these individuals are not independent, such that managers can affect employee health. For example, Swedish workers giving positive ratings of manager leadership had lower rates of subsequent heart disease (19). Intervening with managers can improve the work environment (20), and contribute to improved worker health (21). At minimum, engaging managers in workplace health programs could improve access for employees, because the managers are usually the ones making decisions about program offerings, and they may influence how easy or difficult it is to participate. However, few prevention efforts target managers. The current study evaluated a psycho-educational program aimed at reducing manager CVD risks, and simultaneously improving their leadership and interactions with subordinates.

The intervention was designed to engage manager interest and reduce barriers to use. The program combined health education (on diet, exercise, and stress) with leadership development exercises to enhance perceived career benefit of participating. For convenient access, the program used Internet-based lessons along with flexible webinar and telephonic support. The Internet has proven to be an effective vehicle for health education with the potential to reach a wider audience than telephone or in-person approaches (22). Subsequently, each manager also could improve skills for leading and managing employees, and had Internet-based health lessons they could share, both of which might benefit their associates.

The current study focused on health-related outcomes following use of the program in a randomized trial with managers from diverse organizations. The program was expected to lead to improvements in manager healthy lifestyle (diet and exercise) and reductions in stress and negative mood or hostility. In the longer term, improvements in diet and exercise might lead to weight loss, which the study also investigated, using physical measurements of weight, body mass index, body fat percentage, and waist circumference. Adding these objective measures represents an enhancement to previous studies of supervisory interventions (20, 23).

Method

Sample

The study included 145 managers from eight different organizations. Organizations included a private university (n = 19), city & county government (combined for analytic purposes; n = 11 and 13, respectively), an international aid organization (n = 11), a national transportation company (n = 15), a hospital (n = 16), a travel service (n = 19), and a health and fitness provider (n = 41). The organizations were large, ranging from about 1,200 to 47,000 employees (Mdn = 4,300), and most operated in multiple locations. Managers worked throughout the United States and, with the international aid organization, in Africa and Asia. Workplace health promotion programming varied among the organizations, and in some cases among the separate locations for each organization. Almost all organizations had some fitness programming and some manner of incentives; diet programs, stress reduction, and health assessments each were available in about two thirds of the organizations. However, programs supporting executive health were rarely available. Overall, the university and the transportation company had the richest set of options, and the hospital and the international aid organization had the most limited set.

Researchers recruited managers through their employer, following the organization’s decision to participate. For safety reasons, pacemaker users were ineligible for the study, which promoted changes in diet and exercise, and also used a device measuring body fat with a weak electrical charge. Several groups of managers were eligible to use the program and to complete surveys, but were ineligible for biometric data collection. These were: international managers (to avoid the cost and time for shipping measurement equipment) and managers who were pregnant or handicapped (whose values and changes for these measures would have been misleading). Therefore the baseline sample size for physical measurements (n = 127) was smaller than for the surveys (n = 142).

Procedure

Researchers cooperated with organizational representatives, usually from the human resources department, to initiate the study and begin recruitment. After each organization agreed to participate, organizational representatives sent a standardized e-mail notice to managers, informing them of the opportunity to take part in the study and use a newly-developed training program on health and leadership development. The e-mail also contained contact information for the researchers, who handled all further recruitment and enrollment activities. Following the introductory announcement, organizational representatives had no further role in the study.

Managers completed assessments at three points in time. Two assessments came before any use of the training program, and the third was a posttraining follow-up. First, managers completed a brief screening survey to determine their interest and eligibility for the study. It also collected contact information for use in future communication, random assignment, and data collection efforts. Once investigators established eligibility, they gave each manager additional study details. Managers wishing to continue with the study then beganthe second assessment wave, the study baseline. It included a comprehensive survey measuring demographic background, diet and exercise habits, mental and physical health indictors, job role, productivity, leadership styles, support from supervisors, and availability of health and wellness programming at work. After completing the survey, managers were mailed a measuring kit to record their height, weight, and other measures, using a standard set of tools supplied by the research team. Measuring kits included a cloth tape measure and ruler, a Taylor glass electronic scale (model number 7523EF), a hand-held electronic Omron fat loss monitor (model number 4BF-306C) that computed BMI and body fat percentage, and a set of detailed instructions for using the materials. Instructions were adapted from established anthropometric procedures (24).

After completing baseline assessments, managers received randomized group assignments. Those assigned to the experimental group were oriented to the program by telephone and were free to begin. They had access to the program for approximately 6 months. During that time, employees reporting to experimental-group managers also were asked to complete surveys, but those data were not used in the current study. Managers in the control group had no project-related training or activities. Six months after the baseline, managers completed the third set of assessments, featuring the same survey and biometric measures.

Data collection used a combination of Internet and mailed methods. Managers completed surveys over the Internet, except for 3 individuals who requested paper-and-pencil forms. Managers recorded their biometric measures on paper and then returned the data and the measuring kit using a prepaid shipping label. An informed consent document accompanied each survey and participants had to indicate their agreement. All procedures were reviewed and approved by an independent Institutional Review Board.

Training Program

The Internet-based program tested in the study, ExecuPrev™, trained managers to modify attitudes and behaviors, and built motivation to be healthy and effective leaders. Users were trained to (1) take actions to improve lifestyle habits (diet, exercise, stress, and mood management), (2) consider and enhance their impact on others at work as leaders and health role models, (3) promote and support workplace wellness programming, (4) continually assess their health and leadership orientation, (5) reflect on and improve working conditions for themselves and their associates, and (6) integrate these actions in a planning system for continuous improvement.

The program had two main topic areas, health (a component called “livewell”) and leadership development (a component called “leadwell”). The two were connected and cross-referenced one another, but the lessons were separate. The focus for this study was the health component, livewell. These lessons drew from a text on managerial health (25) and covered health risks and strengths along various dimensions (e.g., physical, emotional), and their personal and organizational outcomes. Lessons were animated and narrated, and were supported by other interactive learning elements such as self-assessments, simulation tools, short videos of industry experts, and more detailed reading materials. Users also could participate in web-based coaching and seminars (“webinars”). The program encouraged users to take action and experiment with new behaviors in their health and work situation. ExecuPrev™ also provided links to other online health courses (26) providing additional interactive multi-media lessons on specific topics, such as weight loss or stress reduction.

Users were instructed to spend at least 10 hours during the 6-month access period reviewing the program, an average of half an hour each week. However, users could set their own pace and explored the materials in any sequence they wished. An accompanying instruction guide gave a suggested approach for program use, but users could customize their experience.

Measures

Diet

Managers completed three measures of dietary attitudes and changes. Attitude toward a healthy diet was a 12-item scale assessing perceived benefits and convenience of healthy foods (alpha = .73). A sample item was “Eating healthy foods makes me feel better.” Ratings used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Dietary self-efficacy was a 6-item measure of confidence in being able to make dietary improvements, such as “How confident are you that you have the skills to cut down on the amount of fat in your diet?” (alpha = .91). Ratings used a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (“not confident”) to 5 (“extremely confident”). Dietary stage of change drew from stage-oriented theories of behavior change (27) to reflect actions or intentions to eat a healthy diet. It used 4 items (e.g., “Have you generally been adhering to a low fat diet?”) rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (“no, and I do not intend to in the next 3 months”) to 5 (“yes, I have been for more than 3 months”). Intermediate response options showed intentions, such as “no, but I intend to in the next month.” The scale had an alpha coefficient of .76. All three measures originated in the Health Behavior Questionnaire (26).

Exercise

Two survey measures reflected exercise. Leisure time exercise (28) was a weighted composite of the typical weekly frequency for strenuous (e.g., running or digging), moderate (e.g., fast walking or gardening), and mild physical activity (e.g., golf or light cleaning). Scores were a sum of 9 times the strenuous activity frequency, 5 times the moderate frequency, and 3 times to mild frequency. Alpha for the weighted sums was .56. Exercise stage of change was a single item indicating actions or intentions for increasing exercise (26), using response options described above for dietary stage of change.

Mental health

Four measures characterized manager mental health. Symptoms of distress (26) was a 15-item scale capturing the frequency of various physical and emotional symptoms of stress (e.g., “muscle tension”); the alpha coefficient was .87. Ratings used a 4-point rating scale, from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“nearly every day”). Eight items measured hostile attitudes (29), such as “I can’t help being a little unpleasant with people I don’t like” (alpha = .71). These items used a 4-point scale, from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). Two single-item stages of change measures capture actions or intentions to reduce stress and manage mood, respectively. These used the same response options described above.

Biometric measurements

Biometric measures included weight (in pounds), waist circumference (WC, in inches), Body Mass Index (BMI), and body fat percentage (BFP). Participants recorded these values on three different days over a period of approximately 1 week. For analytic purposes, the median of the three observations for each measure served as outcome variables. The median was more resistant than the mean to extreme values, offering more protection against a single measurement taken incorrectly or under different conditions from the others.

Covariates

Analyses included several background covariates, based on their plausible relationship to the attitudes, behaviors, symptoms, and physical measurements under study. Participants were asked to indicate gender, age (in years), and hypertension status. Managers responded to two questions on hypertension: whether they had been diagnosed with hypertension, or whether they were currently taking medication for the condition. A “yes” to either question was coded as indicating the presence of hypertension. Each manager’s organizational affiliation was also included, to gauge and control for organization differences.

Statistical Analysis

Tests of program effectiveness relied on mixed models for repeated measures. These analyses were similar to traditional repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), but they employed maximum likelihood estimation and included participants with incomplete data on outcome measures (30). The capacity to accommodate incomplete data was important because some participants left the study prior to completing follow-up assessments, or left some survey items blank. Using more of the data made the resulting estimates more precise (and tests more powerful), and validity of the inferences rested on less restrictive assumptions about the missing data (31). In particular, the mixed model results could be interpreted as though no data were missing provided that, after taking into account the value of the outcome measured at baseline as well as experimental group assignment and other covariates, missing the follow up was unrelated to the value the respondent would have reported. Analyses were conducted using the MIXED procedure of SPSS.

Specification for the mixed models was as follows. The central factors in the analyses were group assignment (managers who used the program versus control managers), time (baseline versus 6-month follow-up), and their interaction. Manager gender, age, hypertension status, and worksite were included as covariates. Analyses of biometric measures omitted hypertension because of the complex relationship between blood pressure at study admission and weight (or other physical measures) in the past. Adjusting for hypertension status, therefore, could lead to adjusting baseline weight for earlier values of weight, rendering interpretation of these measures ambiguous. Formal tests of program effectiveness used the group-by-time interaction, which examined group differences in change between baseline and follow-up, controlling for the covariates. In general, the program was deemed to be effective when the program managers reported significantly greater improvement than control managers reported over the same period. The magnitude of the “difference in differences” was estimated from the adjusted means by subtracting the baseline mean from the follow-up mean for the program group, and then subtracting the corresponding difference in the control group (32). That estimate appears in the tables below as the “intervention effect.”

In addition, two potential sources of subgroup differences were addressed. First, descriptive examination of the data had suggested possible worksite differences in program effectiveness, and the mixed models tested that possibility explicitly. An initial set of analyses included interactions of worksite with group and with time, and a three-way interaction of all these factors. In most cases, the worksite interactions were not significant, and interpretations relied on a reduced model that omitted them. The few cases where the group-by-time-by-worksite interaction was significant were noted below, and interpretation was supplemented with an examination of the range of intervention effects across worksites. Finally, analyses of the physical biometric measurements were conducted for men and women separately, rather than using gender as a covariate, to improve interpretability. Gender differences in these measures have been well established (33), leading to gender-specific interpretational cutoffs for waist circumference (34) and BFP (33).

Results

Sample description and attrition

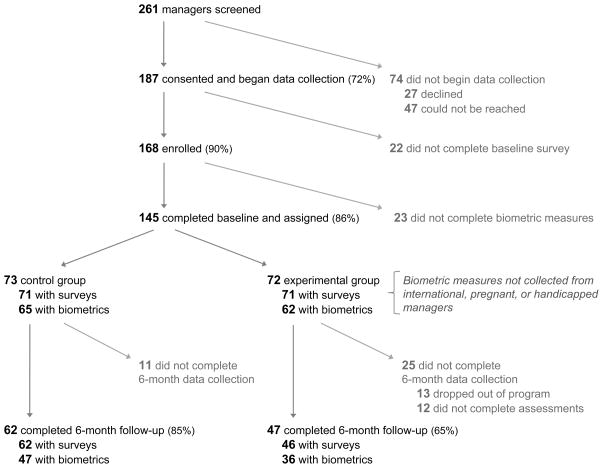

The sample for analysis included 145 managers. Figure 1 shows the disposition of cases throughout the sequence of screening, enrollment, and data collection. Although the design had called for all managers to complete the baseline survey and biometric measures (except for managers who were located internationally, pregnant, or handicapped), in a few cases that was not possible and managers enrolled despite missing one assessment or the other. Overall, 75% of managers were reassessed at 6-month follow-up though, as the Figure shows, follow-up rates differed by condition.

Figure 1.

Participation in trial of ExecuPrev™ training program for manager

Table 1 describes the background for the sample. The managers were predominantly women (64%) and white (82%) or African American (9%); 7% considered themselves to be Hispanic or Latino. The average age was 41.5 years (with a standard deviation of 10.3 years). The managers were diverse in their educational background and experience with the company.

Table 1.

Sample description, percentages.

| Experimental (n = 72) | Control (n = 73) | Total (n = 145) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 72 | 56 | 64 |

| Age, years [Mean (SD)] | 39.7 (9.7) | 43.2 (10.6) | 41.5 (10.3) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Racial background | |||

| White | 86 | 79 | 82 |

| African American | 7 | 10 | 9 |

| Asian | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Other/more than one race | 3 | 8 | 6 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or living as married | 72 | 78 | 75 |

| Single | 23 | 18 | 20 |

| Divorced or separated | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Education level | |||

| Less than Bachelor’s degree | 13 | 27 | 20 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 47 | 39 | 43 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 40 | 34 | 37 |

| Management level | |||

| First-level manager | 62 | 56 | 59 |

| Middle manager | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Senior or upper-level manager | 13 | 18 | 16 |

| Years with company | |||

| Less than 1 | 9 | 4 | 6 |

| 1 to 3 | 19 | 11 | 15 |

| 3 to 5 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| 5 to 9 | 19 | 17 | 18 |

| 10 or more | 44 | 56 | 50 |

| Hypertension | 20 | 18 | 19 |

Note: Sample sizes vary from 140 to 145, owing to missing data.

Comparisons of background characteristics between the experimental and control groups (also in Table 1) assessed the similarity of participants in the two conditions. These comparisons identified only two significant differences: the experimental group was slightly younger (M = 39.7 versus 43.2, SD = 9.7, 10.6, respectively), t(141) = −2.05, p = .04, and had a higher percentage of women (72% versus 56%), χ2(1) = 4.06, p =.04. However, both represented only a modest correlation with condition assignment (r = −.17 for age and .17 for gender), and both appeared in the analyses as covariates, adjusting for any potential bias. Other characteristics, including hypertension status, employer organization, race/ethnic minority status, and managerial level, did not differ between conditions.

The same background characteristics also were considered in connection with study attrition, as were baseline values of the outcome measures. However, none of these factors had a significant relationship to dropout, nor did those relationships differ between conditions. Thus, although experimental group managers were more likely to leave the study prior to completing the 6-month follow-up (35% versus 15%), that did not appear to be a function of their background. Rather, several managers who dropped out indicated they did not have time to keep up with the program. These findings, combined with an analytic approach that incorporated incomplete data, suggested attrition was unlikely to bias study results substantially. Finally, experimental group managers reported reasonable adherence to the program on the follow-up survey, with 95% indicating they completed at least one health lesson, and 58% indicating they completed most (at least three out of four) of the lessons (and they reported similar levels of use for the leadership lessons, with 91% and 51% respectively).

Self-rated Changes

Changes in self-rated attitudes, behavior, and symptom measures appear in Table 2. The key topic areas for these ratings were diet, exercise, and mental health. In the diet area, both attitudes toward a healthy diet and dietary self-efficacy showed significant intervention effects. Effects on attitudes toward a healthy diet also varied significantly across worksites, making the effect shown in Table 1 (0.25) an overall estimate. Tests of simple effects based on the overall effect indicated significant improvement in attitudes for managers in the program group, F(1,97.26) = 13.78, p = .00, compared with a nonsignificant decrease for managers in the control group. Worksite-specific estimates ranged from −0.31 to 0.89. These effects were significant in the travel services, 0.89, t(95.56) = 4.21, p = .00, and international non-profit settings, 0.52, t(88.92) = 2.37, p = .02. For self-efficacy, the experimental group improved in their ratings by almost half a point more than the control group (0.43). Tests of simple effects showed significant improvements in the program group, F(1,115.25) = 19.37, p = .00, coupled with no significant change in the control group.

Table 2.

Adjusted means, standard errors, and test statistics for changes in attitudes, behaviors, and health symptoms.

| Experimental

|

Control

|

Intervention Effect | Test Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | Baseline | 6 Months | |||

| Diet | ||||||

| Attitude toward healthy diet a | 3.45 (0.06) | 3.68 (0.08) | 3.58 (0.06) | 3.56 (0.06) | 0.25 (0.08) | F(1,93.69) = 10.65, p = .00 |

| Dietary self-efficacy | 3.63 (0.09) | 4.08 (0.11) | 3.82 (0.09) | 3.85 (0.10) | 0.43 (0.14) | F(1,111.08) = 9.23, p = .00 |

| Dietary stage of change | 3.84 (0.13) | 4.10 (0.16) | 3.64 (0.13) | 3.72 (0.14) | 0.17 (0.19) | F(1,115.17) = 0.86, p = .36 |

| Exercise | ||||||

| Leisure time exercise | 40.67 (3.41) | 51.85 (4.12) | 41.47 (3.30) | 43.78 (3.47) | 8.87 (4.82) | F(1,106.46) = 3.38, p = .07 |

| Exercise stage of change | 4.05 (0.14) | 4.43 (0.17) | 3.78 (0.14) | 3.94 (0.15) | 0.22 (0.22) | F(1,108.94) = 0.93, p = .34 |

| Mental Health | ||||||

| Distress a | 15.02 (0.94) | 11.50 (1.22) | 12.37 (0.93) | 12.67 (0.97) | −3.82 (1.46) | F(1,102.01) = 6.84, p = .01 |

| (1.47) | (1.84) | (1.44) | (1.54) | (2.41) | ||

| Hostile attitudes | 16.60 (0.39) | 15.83 (0.54) | 15.13 (0.39) | 15.35 (0.47) | −0.99 (0.59) | F(1,100.55) = 2.79, p = .10 |

| Stress stage of change | 3.92 (0.18) | 4.28 (0.21) | 3.70 (0.17) | 3.94 (0.18) | 0.12 (0.25) | F(1,113.25) = 0.23, p = .63 |

| Mood stage of change | 3.99 (0.16) | 4.44 (0.19) | 4.06 (0.16) | 4.11 (0.17) | 0.40 (0.24) | F(1,112.07) = 2.63, p = .10 |

Note: Sample sizes vary from 136 to 142, owing to missing data.

Intervention effect also interacts significantly with worksite, see text for details.

In the exercise area, frequency of exercise showed a marginally significant intervention effect. The experimental group reported a greater increase in the (weighted) frequency of exercise than the control group (8.87). Although the change was large in magnitude, substantial individual differences in exercise patterns affected statistical significance levels.

In the mental health area, the most substantial effect was for distress, although hostile attitudes and mood “stage of change” showed marginally significant intervention effects. For the distress measure, the estimated intervention effect (−3.82) suggested managers in the experimental group reported an average decrease in their scores almost 4 points larger than control managers. Tests of the simple effects showed experimental group managers reporting significantly fewer distress symptoms following use of the program, F(1,107.99) = 9.02, p = .00, compared with no significant change among control managers. Intervention effects on distress also differed significantly across worksites. Worksite-specific estimates ranged from −12.11 to 4.48. Estimates were significant among government workers, −12.11, t(118.22) = −2.59, p = .01, and travel services, −11.06, t(105.51) = −2.70, p = .01.

Biometric Changes

Changes in weight, WC, BMI, and BFP appear in Table 3. Measurements for men and women are presented separately for greater interpretability. Initial examination of these data identified two probable outliers among the male participants, who lost substantially more weight than other men during the study period. These individuals, both in the experimental group, lost 23.0 and 23.6 pounds, respectively, and the other men with complete data ranged between a 15.5 pound loss and a 13.8 pound gain. Although the mixed model analyses described below do not use the change scores directly, including or excluding these two cases altered the estimates of program effectiveness. Accordingly, these two participants were excluded from Table 3 and associated tests of significance. In contrast, the women had more variability in their physical measurements, and the sample did not contain marked outliers. Women’s weight changes ranged from a 19.2 pound loss to a 25.6 pound gain. Excluding participants with more extreme weight changes did not alter the substantive conclusions of the results.

Table 3.

Adjusted means, standard errors, and test statistics for changes in physical measurements, by gender.

| Experimental

|

Control

|

Intervention Effect | Test Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | Baseline | 6 Months | |||

| Men (n = 41) | ||||||

| Weight (pounds) | 203.63 (9.23) | 204.62 (9.37) | 195.15 (6.46) | 196.43 (6.51) | −0.28 (2.69) | F(1,20.93) = 0.01, p = .92 |

| Waist (inches) | 38.35 (1.01) | 38.23 (1.11) | 38.09 (0.71) | 37.52 (1.01) | 0.46 (0.96) | F(1,22.81) = 0.36, p = .56 |

| Body Mass Index | 29.89 (1.25) | 30.27 (1.30) | 27.42 (0.87) | 27.30 (0.89) | 0.50 (0.60) | F(1,21.68) = 0.68, p = .42 |

| Body Fat (%) | 24.24 (1.38) | 24.54 (1.49) | 21.78 (0.97) | 22.55 (1.01) | −0.47 (0.96) | F(1,22.81) = 0.24, p = .63 |

| Women (n = 85) | ||||||

| Weight (pounds) | 160.30 (5.34) | 159.16 (5.49) | 158.22 (5.50) | 158.66 (5.63) | −1.58 (2.21) | F(1,50.60) = 0.51, p = .48 |

| Waist (inches) | 33.59 (0.74) | 32.60 (0.80) | 33.62 (0.77) | 33.88 (0.80) | −1.26 (0.54) | F(1,49.75) = 5.43, p = .02 |

| Body Mass Index | 26.83 (0.88) | 26.56 (0.92) | 26.90 (0.91) | 27.00 (0.93) | −0.37 (0.41) | F(1,49.87) = 0.81, p = .37 |

| Body Fat (%) | 30.78 (1.01) | 30.48 (1.08) | 31.14 (1.03) | 31.33 (1.08) | −0.49 (0.77) | F(1,51.06) = 0.41, p = .53 |

For men, excluding the two outliers, the intervention was not associated with significant differences in biometric measures. The magnitude of changes was small and similar in both groups. If the extreme cases were included, the pattern of intervention effects would more strongly favor the experimental group, though none of the effects would be statistically significant. Estimates including these cases suggested program users, on average, experienced a tendency for greater reductions than controls in weight (−5.47), WC (−0.59), and BFP (−1.24).

For women, WC showed significant intervention effects. Experimental group women lost about an inch and a quarter more from their waists than control women lost (−1.26). Specifically, tests of the simple effects showed a significant reduction in WC of about 1 inch for the experimental group, F(1, 51.86) = 5.87, p = .02, compared with a nonsignificant increase for the control group. Intervention effect estimates for the other measures also suggested a modest advantage for the experimental group, though group differences were not significant.

Discussion

In recent years there has been a growth of web-based interventions to improve health, particularly for workplace settings (20, 26, 35). These programs have proven effective, but they generally do not distinguish the needs of managers from the needs of other employees. Closer attention to managers is warranted, in part because they carry their own risks for CVD. The current randomized study investigated an Internet-based health program that integrated lessons on healthy lifestyle and leadership, with the goal of reducing CVD risks for managers. Results suggested positive changes in managers’ health-related attitudes and self-perceptions, and some physical improvements, particularly for women.

The sample of managers was diverse in their health status at study baseline, and illustrates several of the challenges managers can face. They were a combination of normal weight and overweight or obese individuals, with men averaging 28.9 BMI and 39.0 inch waist (SD = 5.0, 4.7 respectively) and women averaging 26.5 BMI and 33.4 waist (SD = 5.5, 4.6 respectively). Nineteen percent reported hypertension or related medication. Their profile is typical of many managers (1).

The diversity of the sample has implications for interpreting results. Some managers would consider weight loss a goal and some would not. However, recommended approaches to treating obesity involve changing dietary and physical activity patterns (34), and these changes can have health benefits for normal weight individuals as well, even if weight loss is not their goal. For managers who are overweight or obese, these changes are important first steps toward physical changes that may take longer to achieve. Consequently, we interpret these findings using the following conceptual framework: dietary and exercise changes should occur first, and should apply to the broad set of managers. Physical changes, such as weight loss, will likely take longer to appear, and may not be an appropriate benchmark for all managers, particularly within a 6 month time frame. Results were generally consistent with this framework.

Manager dietary attitudes and self-efficacy both improved significantly in connection with the program. Participants agreed more strongly, for example, that healthy foods were worthwhile and relatively easy to find and prepare, and indicated more confidence that they could eat a healthy diet. Exercise frequency increased as well, though this effect had only marginal statistical significance. Physical changes were more limited, a pattern consistent with change that is more gradual or beginning later in time. Nevertheless, women did experience significant reductions in average waist circumference by the 6-month follow-up assessment.

The other area where program participants reported improvement was distress-related symptoms. Stress is probably more widely written about than other areas of CVD risk for workplace samples (36). Learning to manage stress, therefore, is an important skill. Improvement in manager ability to handle stress seems the most plausible explanation for reduced distress in the current study. With the control group managers (from the same organizations) reporting no change in distress symptoms, it seems unlikely that environmental stressors became less prevalent during the 6 months of the intervention. The small effect on stress stage of change may reflect, in part, the availability of stress-management materials and suggestions, making the contributions of the program in this area more difficult to distinguish.

The overall pattern of results supports the generalizability of intervention effects across organizations. Although testing differential effectiveness was not the primary objective for the study, and the power for these tests is somewhat limited, the results offer little evidence of organizational differences. The only two outcomes with significant organization differences in effectiveness were attitudes toward a healthy diet and symptoms of distress. Both showed a range of possible effects, and the program seemed particularly suited to certain organizations. The travel services organization stood out as having a larger and statistically significant intervention effect for both of these outcomes. That organization has a history of success with Internet-based tools as part of their own work, and therefore may be especially receptive to online programming like ExecuPrev™.

The results also fit with those reported for some other online health-related programs. For example, evaluation of the Health Connection program (26) showed a similar pattern of findings, with stronger effects for dietary changes than for physical activity. Users may find dietary advice easiest to put into practice. The transition from sitting at the computer to exercising may be somewhat more difficult to accomplish. However, recent studies of multicomponent Internet-based weight loss programs (37, 38) suggest they can be effective for overweight individuals, implying the behavior changes that occur are sufficient for these programs to achieve their goal.

Interviews with several managers following the program provided additional qualitative data that hints at the potential for managers as role models. These comments reflect a “ripple” or “cascade” effect: behavior change in one person in a key position can have a multiplier effect on others (25, 39). For example, one manager who lost over 20 pounds described the impact it had on others. “The program got me to think about lifestyle change with a disciplined approach. In 6 months, my cholesterol, sugar, and weight levels dropped. Being on the leadership team I know health effects productivity. I am glad others are now following my example.” That manager’s motivation stemmed in part from the ExecuPrev™ program emphasis on being a healthy role model. Another participant repeated the theme: “I didn’t realize the people who work for me look to me as an example for health and fitness. I get [that] my actions have an impact on them.”

The study is not without limitations. As suggested above, 6 months may not be enough time to learn and implement behavior changes, and experience measurable weight loss. Future studies should include a longer assessment period. Likewise, participants supplied their own physical measures, such as height and weight, and these self-reports could include some error. However, detailed comparisons between survey-based and professionally-measured height and weight in a large national study suggest differences tend to be small, averaging about 1 cm for height and 0.75 kg for weight (40). Current study procedures should yield even less bias, because they rely on a standard set of measuring tools, detailed instructions for use, and multiple measurements over a 1-week period, rather than on free-recall survey items. With the measuring tools, managers would be less prone to guessing or rounding errors. Finally, fewer program users completed the study than control group managers (65% versus 85%). As described above, however, dropout was not related to manager background. Any bias arising from differential attrition therefore is expected to be minimal. Nevertheless, an important issue for future study will be to understand better why some users did not complete the program.

The intervention included multiple components and future research will examine them in more detail. The current study examined overall effectiveness using an “intention-to-treat” approach. Evidence for manager health improvements is an important first step, but the study also gives rise to additional questions about how managers used the program and which components might be the most valuable. The program did not follow a rigid sequence, and different selections or sequences of program options might lead to different outcomes. That question is beyond the scope of the current study but will be a necessary step for improvements to the program. Qualitative data from follow-up interviews suggests mangers generally liked integrating health and leadership, but would like a more structured and delineated sequence.

The study results are promising, even if they are not comprehensive. Managers using the program made improvements in several areas of health. In turn, these managers have the potential to serve as role models and have an impact on others’ behavior. The ExecuPrev™ program offers a means of confronting the challenges of CVD within the workplace.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported entirely by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant Number 5R44HL75965). The interpretations and conclusions, however, do not necessarily represent the position of NHLBI, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

The ExecuPrev program is a propriety product of Organizational Wellness & Learning Systems, in which one of the authors (Dr. Bennett) has a financial interest.

Contributor Information

Joel B. Bennett, Organizational Wellness & Learning Systems, Fort Worth, TX

Kirk M. Broome, Organizational Wellness & Learning Systems, Fort Worth, TX

Ashleigh Pilley, Organizational Wellness & Learning Systems, Fort Worth, TX

Phillip Gilmore, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA.

References

- 1.Association for Professional Executives of the Public Service of Canada. 2007 Study on the Health & Well-Being of Executives: Preliminary Descriptive Results. 2008 Downloaded from: http://www.apex.gc.ca/en/publications/health.aspx.

- 2.Sutherland VJ, Cooper CL. Chief executive lifestyle stress. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 1995;16:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veiga JF. AME’s Executive advisory panel goes for a check-up. Acad Manage Exec. 2000;14:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparks K, Cooper C, Fried Y, Shirom A. The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1997;51:391–408. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M. Overtime work and incident coronary heart disease: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2010 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFrank RS, Konopaske R, Ivancevich JM. Executive travel stress: Perils of the road warrior. Acad Manage Exec. 2000;14:58–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Striker J, Luippold RS, Nagy L, Liese B, Bigelow C, Mundt K. Risk factors for psychological stress among international business travelers. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:245–252. doi: 10.1136/oem.56.4.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kivimäki M, Leino-Arjas P, Luukkonen R, Riihimäki H, Vahtera J, Kirjonen J. Work stress and risk of cardiovascular mortality: prospective cohort study of industrial employees. BMJ. 2002;325(7369):857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7369.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton WN, Chen C, Conti DJ, Schultz AB, Edington DW. The Value of the Periodic Executive Health Examination: Experience at Bank One and Summary of the Literature. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:737–744. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peter R, Siegrist J. Chronic work stress, sickness absence, and hypertension in middle managers: General or specific sociological explanations? Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnethon M, Whitsel LP, Franklin BA, Kris-Etherton P, Milani R, Pratt CA, Wagner GA. Worksite wellness programs for cardiovascular disease prevention: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120:1725–1741. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cesana G, Ferrario M, Gigante S, Sega R, Toso C, Achilli F. Socio-occupational differences in acute myocardial infarction case-fatality and coronary care in a northern Italian population. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:S53–S58. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.suppl_1.s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krantz DS, McCeney MK. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: A Critical Assessment of Research on Coronary Heart Disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:341–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernin P, Theorell T, Sandberg CG. Biological Correlates of Social Support and Pressure at Work in Managers. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2001;36:121–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02734046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller TQ, Smith TW, Turner CW, Guijarro ML, Hallet AJ. Meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:322–348. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen H, Burr TS, Kristensen M, Gamborg M, Osler E, Prescott F, Diderichsen Do factors in the psychosocial work environment mediate the effect of socioeconomic position on the risk of myocardial infarction? Study from the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:886–892. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.013417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmot MG, Bosma H, Hemingway H, Brunner E, Stansfeld S. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet. 1997;350:235–39. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyberg A, Alfredsson L, Theorell T, Westerlund H, Vahtera JM, Kivimaki M. Managerial leadership and ischaemic heart disease among employees: the Swedish WOLF study. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:51–55. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.039362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawakami N, Takao S, Kobayashi Y, Tsutsumi A. Effects of web-based supervisor training on job stressors and psychological distress among workers: a workplace-based randomized controlled trial. J Occup Health. 2006;48:28–34. doi: 10.1539/joh.48.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theorell T, Emdad R, Arnetz B, Weingarten AM. Employee effects of an educational program for managers at an insurance company. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:724–733. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami N, Kobayashi Y, Takao S, Tsutsumi A. Effects of web-based supervisor training on supervisor support and psychological distress among workers: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2005;41:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohman T, Roche A, Reynaldo M. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quick JC, Cooper CL, Gavin JH, Quick JD. Managing executive health: personal and corporate strategies for sustained success. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook RF, Billings DW, Hersch RK, Back AS, Hendrickson A. A field test of a web-based workplace health promotion program to improve dietary practices, reduce stress, and increase physical activity: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e17. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arthur HM, Garfinkel PE, Irvine J. Development and testing of a new hostility scale. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jennrich RI, Schluchter MD. Unbalanced repeated-measures models with structured covariance matrices. Biometrics. 1986;38:967–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL. Exercise physiology: Energy, nutrition, and human performance. 5. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute. NIH publication no. 98-4083. Bethesda, MD: Author; 1998. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Billings DW, Cook RF, Hendrickson A, Dove D. A web-based approach to managing stress and mood disorders in the workforce. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:960–968. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31816c435b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnall PL, Belkic K, Landsbergis P, Baker D. The workplace and cardiovascular disease. Occup Med. 2000:15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothert K, Strecher VJ, Doyle LA, Caplan WM, Joyce JS, Jimison HB, Karm LM, Mims AD, Roth MA. Web-based weight management programs in an integrated health care setting: A randomized, controlled trial. Obesity. 2006;14:266–272. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. A randomized trial comparing human e-mail counseling, computer-automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an internet weight loss program. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1620–1625. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bass B, Waldman D, Avolio B, Bebb M. Transformational leadership and the falling dominoes effect. Group Organ Stud. 1987;12:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stommel M, Schoenborn CA. Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: Findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001–2006. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-421. Downloaded from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/9/421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]