Abstract

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry is a unique technique for sampling dopamine concentration in the brain of rodents in vivo in real time. The combination of in vivo voltammetry with single-unit electrophysiological recording from the same microelectrode has proved to be useful in studying the relationship between animal behavior, dopamine release and unit activity. The instrumentation for these experiments described here has two unique features. First, a 2-electrode arrangement implemented for voltammetric measurements with the grounded reference electrode allows compatibility with electrophysiological measurements, iontophoresis, and multielectrode measurements. Second, we use miniaturized electronic components in the design of a small headstage that can be fixed on the rat's head and used in freely moving animals.

INTRODUCTION

In vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) is a powerful technique that allows real time measurement of electrochemically active biomolecules in both slices and the intact animal brain with nanomolar sensitivity.1 Initially it was developed for the detection of biogenic amines, specifically dopamine, with carbon-fiber microelectrodes. However, in the last decade, the field has witnessed significant growth in the number of analytes that can be measured with FSCV. Detection of adenosine,2 norepinephrine,3 oxygen,4 pH 5 and serotonin6 in brain in vivo have been demonstrated.

Dopaminergic neurons are involved in control of motor activity, learning and motivation. FSCV has been used to detect dopamine release at the terminal fields of dopaminergic neurons in the striatum during such behaviors.7 Technical advances in the construction of miniaturized and highly sensitive electronics as well as improvement in chemical sensitivity of the microelectrodes8, 9 have made it possible to measure endogenous dopamine release in freely moving animals routinely, allowing the study of behavior associated with this release.

While electrochemical detection of neurotransmitter release in behaving animals is a relatively new invention, the recording of single-units, which was pioneered in the early 1950s, is a more traditional method for investigation of brain function in real time.10 This method is based on recording changes in extracellular potential induced by the firing of single neurons. Sharp microelectrodes, with megaohm resistance made of either glass pipettes, insulated metal wires or carbon-fiber microelectrodes are traditionally used for these recordings.11 Multiple cells can be recorded with a single microelectrode. Today, single-unit recording is used in behaving animals and with microelectrode arrays that allow for recording of ensembles of hundreds of neurons.12

About thirty years ago, Julian Millar and co-workers developed instrumentation to perform FSCV and single-unit measurements simultaneously in brain preparations using a single carbon-fiber microelectrode.13, 14 Several advantages result from the use of a single electrode for both measurements instead of separate electrodes,15 including the ability to measure action potentials from the same cells that are being influenced by local neurotransmitter release and the minimization of brain tissue damage. The combined electrochemical/electrophysiological technique (Echem/Ephys) allows the investigation of both presynaptic and postsynaptic events simultaneously. However, the early experiments were restricted to brain slices and anesthetized animals. The original instrumentation was unsuitable for experiments in behaving animals.

In the ensuing twenty years there has been considerable refinement of electronic components pertinent to these experiments, including miniaturized electronic components and custom printed-circuit-board technology. We have taken advantage of these advancements to design a combined Echem/Ephys instrument for behavioral experiments in freely moving rats. Miniature headstages have been designed that can be mounted directly on the rat's head. Also, the traditional 3-electrode potentiostat has been reduced to a simpler 2-electrode potentiostat. Unique insight into brain processing during behavior has been obtained with this instruments as described in prior publications.16, 17

DESIGN

Overview of setup for combined behavioral experiments

A block diagram of the overall system is shown in Fig. 1. Typically, a rat (not shown) is placed in a behavioral chamber (Med Associates Inc, St Albans, VT) with levers, house lights and an audio speaker that are used as behavioral cues during experiments. The operant box is located inside of a Faraday cage, which shields the animal and sensitive components from extraneous electric fields. A set of rotating contacts (slip rings) contained in a swivel (Crist Instrument Co Inc, Hagerstown, MD) is fixed on the top of the behavioral chamber. It allows all of the electrical signals to be passed to and from a tethered headstage located on the animal's head and allows the animal free movement throughout the box. The swivel also provides one fluid port that can be used for administration of drugs. The headstage connects through the swivel to a modular universal electrochemical instrument (UEI) mainframe which contains ancillary circuitry for headstage operation and processing.

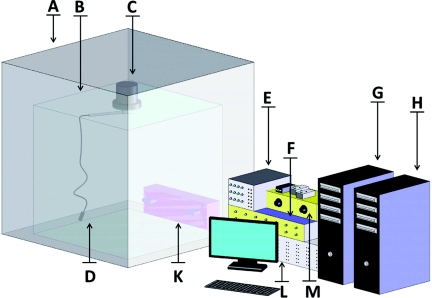

Figure 1.

Setup for combined freely moving Echem/Ephys experiments. The behavioral chamber (B) is located inside grounded Faraday cage (A). Headstage (D) is fixed on rat's head and connected through a rotating swivel (C) with the UEI potentiostat (E). The UEI is interfaced with breakout box (F) though front panel BNC connectors. The voltammetric part of the experiment is controlled by a PC (G) with NI cards that are connected to the breakout box. The electrophysiological signal is high-pass filtered (M) and sampled with NI card on the separate PC (H). The interface of the behavioral chamber components (levers, lights and tones, K) is controlled with Med Associates control module (L) that is connected to a third computer (not shown).

Before the experiment, surgery is performed on the rat under general anesthesia. Holes are drilled in the skull to allow electrode placement in specific brain regions according to stereotaxic coordinates.18 For dopamine measurements, a bipolar stimulating electrode is implanted in the ventral tegmental area or medial forebrain bundle, allowing stimulation of dopaminergic neurons. A guide cannula for the carbon-fiber microelectrode is implanted above the nucleus accumbens, the site of dopaminergic terminals. A Ag/AgCl reference electrode is implanted contralaterally. The animal is allowed to recover for at least three days before experiments. During recording, the carbon-fiber microelectrode is lowered into the nucleus accumbens of an awake animal using a custom made manipulator. The manipulator should be grounded to prevent interference from accumulated static charge during voltammetric measurements. A triangular voltage excursion of –0.4 V to 1.3 V at a scan rate of 400 V/sec is applied at regular frequency for cyclic voltammogram generation. For electrochemical experiments, the triangular wave is repeated at 10 Hz, termed the CV frequency (CVF), and voltammograms are acquired in ∼10 ms. In the combined Ephys/Echem mode, the CV frequency is 5 Hz. The 200 ms delay between cyclic voltammograms is implemented for two reasons. First, it increases the sampling window for electrophysiological data. Second, a longer holding period between cyclic voltammograms facilitates dopamine adsorption, promoting sensitivity.8 Note that in the combined mode the potential of the carbon-fiber microelectrode is allowed to float, and adsorption of dopamine occurs to a lesser extent. Nevertheless, response to dopamine for combined technique is around 60% of response observed with traditional in vivo voltammetry when electrode is held for 100 milliseconds at negative potential between scans.16

The voltammetric experiment, as well as delivery of electrical stimulations, is controlled by a computer running a locally written LABVIEW based program along with three National Instruments PCI DAQ cards (National Instruments, Austin, TX). The cards employed are the NI-6251 (updated version of NI-6052E), which is used for generation of the voltammetric ramp and data acquisition; the NI-6711, which is used for the output of the main clock (CVF), synchronization and generation of stimulation pulses; and the NI-6601, which is used to acquire digital signals associated with the behavior from Med Associates SmartCtrl module (Med Associates Inc, St Albans, VT).

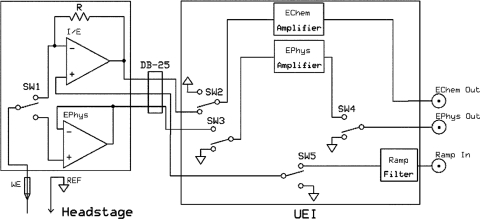

The UEI has a switching module that uses the CVF clock to alternate between Echem and Ephys modes of operation (Fig. 2). There are five CMOS switches with a total of four switches located in the switching module and one switch located on the headstage.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of UEI potentiostat and headstage schematic. Left portion is the headstage that is connected via a DB-25 connector to the UEI chassis (right panel). The reference electrode (REF) is connected to ground. The output from the working electrode (WE) alternates between FSCV (Echem) and electrophysiology (Ephys) preamplifiers with the switch (SW1). Afterwards, signals are sent to a switching module where in Echem mode SW2 is used to connect the headstage to the Echem Amplifier. Switch SW3 grounds input to the Ephys amplifier and switch SW4 grounds the output from the Ephys amplifier to prevent overload. SW5 is used to ground the non-inverting input of the I/E converter when the system operates in Ephys mode. Headstage is connected to UEI via DB-25 cable.

The electrophysiology signal from the UEI is fed to a Grass model AM 10 high-pass filter and an audio speaker (Grass Product Group, Astro-Med Inc, West Warwick, RI) to provide audio output of neuronal activity. The same signal is also filtered using a Dual Channel Butterworth/Bessel Model 3382 8-pole filter (Krohn-Hite Corporation, Brockton, MA) and is fed to a computer equipped with an NI-6040 DAQ card and Plexon software (Plexon Inc, Dallas, TX) for unit recording and analysis.

Design of potentiostat for in vivo voltammetry

For FSCV measurements, 2-electrode circuitry is used. In this configuration, a voltage ramp is applied between a pair of electrodes and the resulting current is measured. This differs from the traditional 3-electrode design in which oxidation/reduction takes place at the working electrode according to the voltage applied to the auxiliary electrode. In some systems where the resistance of the media is high, there can be a substantial difference between the desired voltage and the voltage that appears at the working electrode (due to the iR drop in the solution). Therefore, a third reference electrode is utilized to sense the actual voltage in proximity to the working electrode and, through feedback circuitry, to increase the voltage applied to the auxiliary electrode to offset the iR drop.19 However, in this application the 2-electrode scheme is advantageous. First, the hazard of accidental electrical shocks to the experimental animal from the auxiliary electrode is avoided. Second, the 3-electrode scheme is unnecessary for compensating iR drop with microelectrodes. The resistance of the electrochemical cell with a cylindrical microelectrode is proportional to the logarithm of the distance between the working and auxiliary electrodes.20, 21 This means that the majority of the potential drop occurs immediately adjacent to the microelectrode making it difficult to place a reference electrode in close proximity without causing damage in the measurement region. In addition, brain tissue has a relatively high conductivity (ionic strength is greater than 0.1 M), so the iR drop for microelectrodes is small and does not significantly affect the value of the applied potential. This small error can be further reduced by in vitro calibration in solution with resistivity similar to that of the brain microenvironment.22 Additionally, as the triangular wave scan rate increases, the auxiliary electrode introduces complex impedance to the circuitry. This affects the gain and phase margins of potentiostatic circuitry which can cause stability problems leading to undesirable oscillations.23

In both the 3-electrode and 2-electrode potentiostatic methods, the Ag/AgCl electrode is referred to as the “reference electrode”. However, it actually serves different functions in each method. In the 3-electrode scheme, the reference electrode is used to sense the potential near the working electrode, and because it is followed by a high input impedance amplifier, no current flows through the reference electrode. Current flow is from the auxiliary electrode to the working electrode in the 3-electrode method. In the 2-electrode method, current flows from the working electrode to the reference electrode which is at ground potential, so the “reference electrode” is really performing the duty of the auxiliary electrode. However, to preserve consistency with the literature, the Ag/AgCl will be called “reference electrode” throughout this manuscript.

Normally, two-electrode measurements employ an operational amplifier (op-amp) as a current to voltage (I-E) converter with the non-inverting input at ground potential and the inverting input connected to the working electrode. The ramp signal is inverted and then applied directly to the reference electrode and the current is measured by the I-E converter. This design is used in EI-400 potentiostat (ESA Biosciences Inc, Chelmsford, MA). The main drawback of this approach is that it makes it difficult to use additional current sources and sinks in the same preparation because their current will flow to the working electrode. Also, the working electrode is held at ground potential instead of at the desired potential due to the virtual ground present at the input of the op-amp.

In the UEI, the headstage consists of an operational amplifier in I-E mode with the ramp signal applied to the non-inverting input while the working electrode is connected to the inverting input. In this case, the voltage at the microelectrode follows the voltage applied to the non-inverting input of the amplifier. At the same time, the current that flows between the working and the reference electrodes (as a result of the applied voltage) is summed at the inverting input and adds to the voltage seen at the output of the amplifier. The output voltage then becomes

| (1) |

where Vo is output voltage, IIN is input current, RF is feedback resistor and VR is ramp voltage. Since the output Vo has the added ramp voltage, VR, and it should be subtracted in hardware or software to produce a signal related to the voltammetric current.

The realization of this 2-electrode approach proved to be beneficial since it allowed for a number of experimental setups that are complimentary with traditional FSCV experiments in animals. For example, iontophoresis which is quantitative drug delivery technique24 is compatible with presented potentiostat design because introduction of extra current source in iontophoretic barrel does not disturb measuring of electrochemical current on the working electrode (Fig. 3a). All of the currents (electrochemical and iontophoretic) flow to the reference electrode.

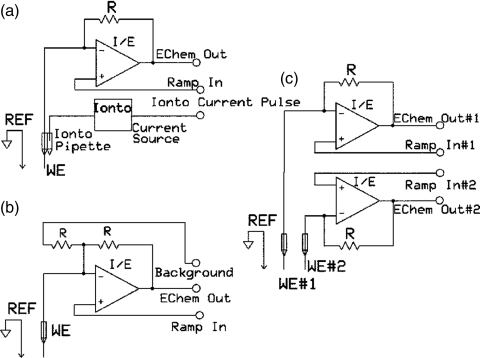

Figure 3.

Schematic circuitries for headstages with iontophoresis, analog background subtraction and multiple electrode recording. For the iontophoretic setup, an additional current source for drug ejection is added to the circuitry (A). For analog-background subtraction, an additional input through the gain resistor is added to the summing point of the amplifier (B). Recordings with multiple independent microelectrodes can be performed by using a separate amplifier for each microelectrode (C).

The use of fast scan rates leads to high background currents, which are significantly higher than the current for oxidation of the analyte (i.e. dopamine). Traditionally, numerical background subtraction in software is used to remove this current. However, analog-background subtraction is possible and it has number of advantages such as an increase in amplifier dynamic range, a decrease in digitization noise and compensation for background drift. Recently, analog background subtraction was realized by a simple modification to the headstage circuitry.25 An additional input for inverted background current was added to the summing point of the amplifier (Fig. 3b). The background current is recorded in the absence of analyte and stored in the computer. During measurements, a DAC is used to generate the inverted background current, which is sent through the second gain resistor and subtracted from the current flowing from the working electrode.

Another important advantage of the UEI is the ability to execute measurements with multiple independently controlled microelectrodes. In this setup multiple operational amplifiers can be used with a separate amplifier for each microelectrode and the same grounded reference (Fig. 3c). The same voltammetric ramp can be applied to all microelectrodes26, 27 to sample dopamine in different brain regions simultaneously. Alternatively, different voltammetric ramps can be applied to each electrode each of which is suited for specific analyte such as dopamine and oxygen or 5-hydroxytryptamine.28

Headstage design for combined FSCV and electrophysiological measurements in freely moving animals

Typical stand-alone electrophysiological measurement of single-unit impulses is carried out with a simple voltage follower amplifier, which outputs the potential between a pair of electrodes. In our case, the measurement is between the same electrodes as that used for FSCV, that is, between the carbon fiber microelectrode and the Ag/AgCl electrode. Because the input impedance of the buffer amplifier is extremely high, the signal amplitude is unaffected by relatively high impedance of the electrodes.

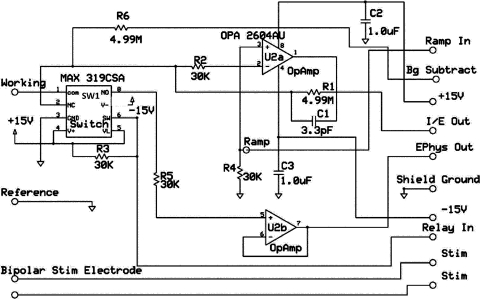

To perform simultaneous measurements in freely moving animals, a miniaturized headstage has been designed (Fig. 4). The headstage is designed to fit on the rat's head without affecting its behavior and it weighs just 2.5 g. A DB-25 connector attaches to the swivel in the behavioral chamber which, in turn, connects to the UEI mainframe. The main feature of the headstage is the surface-mount OPA 2604AU (Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX) dual operational amplifier (Fig. 5). One amplifier on this chip (U2a) functions as a high gain current transducer. The other one (U2b) is arranged as a voltage follower for the electrophysiology signal. The system flips between Ephys and Echem mode by CMOS analog switch (SW1) MAX 319CSA (Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX) that is triggered by a digital “Relay In” signal. Particular care has been taken to select CMOS switches that have been optimized for low leakage, low charge transfer, low and matched input capacitance, and low noise. Because typical I-E converter transconductance gains vary from 1V/μA to 1V/10 nA (RF values of 1 MΩ to 100 MΩ) depending on the application, and because the redox currents are on the order of nanoamperes or less, leakage currents for the CMOS switches in the off state must be far below these levels. We chose the MAX 319CSA CMOS switch for the use on the headstage. It has leakage current 250 pA and open resistance below 20 Ω. Charge transfer from the CMOS switch control line into the inputs and outputs must also be low in order to avoid amplifier saturation during switching. The CMOS switch open and closed terminal capacitances need to be low and relatively well matched to minimize excess charging currents during the switching process. For MAX 319CSA, on and off capacitances match and are equal to 8 pF. In addition, the analog path noise of the CMOS switch is of concern since the switches work on the input side of the amplifier and therefore contribute directly to the total circuit noise.

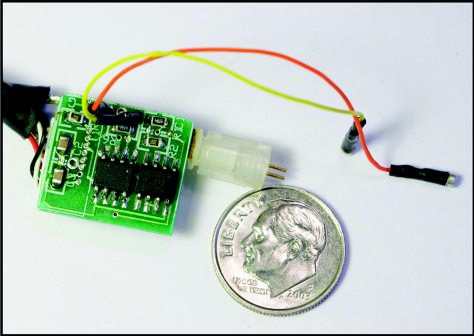

Figure 4.

Photo of miniaturized headstage used for combined Echem/Ephys freely moving experiments adjacent to a U.S dime. The orange and yellow connecting wires are for reference and working electrodes. The copper connectors on the right are for bipolar stimulating electrode. One of the SO chips is the analog switch and the other is the op amps. The cable on the left of the printed circuit board leads to a DB-25 connector.

Figure 5.

Circuitry for headstage used for combined Echem/Ephys freely moving experiments. The operational amplifiers, switch, resistors and capacitors are all on a single printed circuit board (Fig. 4). The outputs and inputs on the right hand side of the diagram are interfaced through a DB-25 connector.

Design of the UEI chassis

The supporting electronics for the headstage reside in the main UEI chassis. In present models, a low noise linear regulated power supply for all of the circuitry needed for FSCV and electrophysiological measurements is housed in a separate chassis. This separate chassis is located at a distance from the mainframe in order to reduce electromagnetic noise coupled from the transformer to sensitive circuitry. The UEI mainframe has a backplane for inserting various support modules. This allows for maximum flexibility in construction of multi-channel systems, addition of filtering hardware, and addition of future enhancements. In the simplest case, two plug-in modules are used. One module contains additional variable post-amplification for both the electrochemical and the electrophysiological signals and routes signals to and from the headstage. The second module is used for analog low pass filtering of the digitized triangular signal before it is directed to the headstage. The filter removes the staircase transitions from the ADC output which can noise due to unwanted C*dV/dt charging of the electrode capacitance at each transition. Other plug-in modules consist of a video text module that synchronizes real-time video with the control software and multi-channel FSCV modules.

Electronic design for switching control module

The switching control modules alternate between the Ephys and Echem mode of operation.29 Switching is triggered by a “Relay In” signal that is received from the computer via a BNC on the front panel of the UEI instrument. Analog CMOS switches U5 (SW2 and SW5) and U2 (SW3 and SW4) are MAX 314 CMOS switches (DIP, Maxim, Sunnyvale, CA), that have a rapid (>1 μs) switching time with low (10 Ω) on-resistance.

In Echem mode, the I/E signal received from the headstage is sent to the electrochemical amplifier. The triangular wave (Ramp In) is computer generated and received from BNC connector on UEI front panel and sent to the headstage (Ramp Out). In Echem mode, the “Ephys In” signal from the headstage, the output to the spike amplifier (Ephys Out to Amp), and the “Ephys Out” to UEI front panel are all grounded. In Ephys mode, the “Ephys In” signal received from the headstage is sent to the spike amplifier. Afterwards, it is sent out on front panel BNC “Ephys Out”. Voltammetric ramp (Ramp In), electrochemical input from the headstage (I/E In) and input to electrochemical amplifier (I/E Out to Amp) are disconnected. A “RELAY IN” LED on the front panel notifies the user whenever the system switches to the Ephys state and it is controlled by circuitry shown on the right bottom corner.29

Electronic design of the electrochemical amplifier with variable gain

The voltammetric signal is received from the switching control model after being amplified on the headstage and it is further amplified with variable gain.29 The main amplifier U2a is based on dual low noise LT1113 chip (Linear Technology, Milpitas, CA). The gain of this amplifier can be chosen using push buttons on UEI front panel (K3, K4, and K5) and can be set to X1, X2, X5, and X10 multiplies of the headstage gain. Front panel LEDs mark the gain selected. A CD4017 (National instruments, Austin, TX) counter chip is used to control the LEDs and switch the gain.

To notify the user about overload in I/E signal, an overload detector is constructed with U5a and U5b, which are LM393 low power low voltage dual comparator (National Semiconductors, Santa Clara, CA). In a case of an overload, a red LED on the front panel illuminates when the I/E current exceeds the amplifier output limit.

The LED “on” time is controlled with dual precision monostable CD4538 (National Semiconductors, Santa Clara, CA). After being processed through the first amplifier, the I/E signal is buffered through the second LT1113 chip (U2b) and sent out through a BNC connector on UEI front panel.

Electronic design of the spike amplifier

The electrophysiological signal from neurons (spikes) is received from the switching control module. Amplification of this Ephys signal is done by an OP27 (Analog Devices, Norwood, MA) low-noise precision operational amplifier.29 The signal is amplified by two amplifiers with high gain, U1 and U2 (resistors R5, R12, and capacitors C3, C4). Adjustable high pass filtering is employed to remove the DC component (“Front Panel RC”). Overload can latch amplifiers used with high gain. To prevent it, diode pairs (D1, D2, D3, and D4) are used to limit the maximum input voltage to ±0.6 V. After being processed through the second U2 amplifier, the Ephys signal is sent back to switching control module. Switching is utilized on the Ephys signal because active gating is not always available on the various third party hardware used for spike processing (i.e., Plexon).

CONCLUSIONS

FSCV combined with single-unit electrophysiology is a powerful technique for studying the dopaminergic system on both the presynaptic and post-synaptic side. The instrument allows chemical and electrical information to be obtained at a single location within the brain. Application of this technique in behaving animals is of particular interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Heien, Joseph Cheer and Catarina Owesson-White for their contribution to the development of the instrumentation and freely moving experimental setup and the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number DA 10900 to R.M.W and R.M.C. and DA 17318 to R.M.C. and R.M.W) for financial support.

References

- Keithley R. B., Takmakov P., Bucher E. S., Belle A. M., Owesson-White C. A., Park J., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 83(9), 3563 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy B. E. K. and Venton B. J., Anal. Chem. 79(2), 744 (2007). 10.1021/ac061820i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Kile B. M., and Wightman R. M., Eur. J. Neurosci. 30(11), 2121 (2009). 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07005.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venton B. J., Michael D. J., and Wightman R. M., J. Neurochem. 84(2), 373 (2003). 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takmakov P., Zachek M. K., Keithley R. B., Bucher E. S., McCarty G. S., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 82(23), 9892 (2010). 10.1021/ac102399n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi P., Dankoski E. C., Petrovic J., Keithley R. B., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 81(22), 9462 (2009). 10.1021/ac9018846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. L., Hermans A., Seipel A. T., and Wightman R. M., Chem. Rev. 108(7), 2554 (2008). 10.1021/cr068081q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heien M. L. A. V., Phillips P. E. M., Stuber G. D., Seipel A. T., and Wightman R. M., Analyst 128(12), 1413 (2003). 10.1039/b307024g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takmakov P., Zachek M. K., Keithley R. B., Walsh P. L., Donley C., McCarty G. S., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 82(5), 2020 (2010). 10.1021/ac902753x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon Roger and Prochazka A., Methods for neuronal recording in conscious animals (Wiley, New York, 1984). [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey D. R. and Schmidt E. M., Extracellular single-unit recording methods (Humana, Clifton, N.J., 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Nicolelis Miguel A. L., Methods for neural ensemble recordings, 2nd ed. (CRC, Boca Raton, 2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar J. and Barnett T. G., J. Neurosci. Methods 25(2), 91 (1988). 10.1016/0165-0270(88)90144-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamford J. A., Palij P., Davidson C., Jorm C. M., and Millar J., J. Neurosci. Methods 50(3), 279 (1993). 10.1016/0165-0270(93)90035-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M. T., Dunwiddie T. V., and Gerhardt G. A., Brain Res. 518(1–2), 149 (1990). 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90966-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheer J. F., Heien M. L. A. V., Garris P. A., Carelli R. M., and Wightman R. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102(52), 19150 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0509607102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owesson-White C. A., Ariansen J., Stuber G. D., Cleaveland N. A., Cheer J. F., Wightman R. M., and Carelli R. M., Eur. J. Neurosci. 30(6), 1117 (2009). 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06916.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos George and Watson Charles, The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 5th ed. (Elsevier, Amsterdam,2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P. T. and Heineman W. R., Laboratory Techniques in Electroanalytical Chemistry (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R. S., Mccurdy C. W., and Mccreery R. L., Anal. Chem. 54(13), 2356 (1982). 10.1021/ac00250a049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman R. M. and Wipf D. O., in Electroanalytical Chemistry: A Series of Advances, edited by Bard Allen J. (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1989), Vol. 15, p. 267. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen E. W., Wilson R. L., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 58(4), 986 (1986). 10.1021/ac00295a073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amatore C. and Maisonhaute E., Anal. Chem. 77(15), 303a (2005). 10.1021/ac053430m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr N. R., Kile B. M., Carelli R. M., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 80(22), 8635 (2008). 10.1021/ac801547a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans A., Keithley R. B., Kita J. M., Sombers L. A., and Wightman R. M., Anal. Chem. 80(11), 4040 (2008). 10.1021/ac800108j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachek M. K., Park J., Takmakov P., Wightman R. M., and McCarty G. S., Analyst 135(7), 1556 (2010). 10.1039/c0an00114g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachek M. K., Takmakov P., Park J., Wightman R. M., and McCarty G. S., Biosens. Bioelectron. 25(5), 1179 (2010). 10.1016/j.bios.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachek M. K., Takmakov P., Moody B., Wightman R. M., and McCarty G. S., Anal. Chem. 81(15), 6258 (2009). 10.1021/ac900790m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3610651E-RSINAK-82-056107 for circuitry for switching control module (FIG S1), circuitry for electrochemical amplifier with variable gain (FIG S2) and for circuitry for the neural spike amplifier (FIG S3).