Summary

In randomized clinical trials, the use of potentially subjective endpoints has led to frequent use of blinded independent central review (BICR) and event adjudication committees to reduce possible bias in treatment effect estimators based on local evaluations (LE). In oncology trials, progression-free survival (PFS) is one such endpoint. PFS requires image interpretation to determine whether a patient’s cancer has progressed, and BICR has been advocated to reduce the potential for endpoints to be biased by knowledge of treatment assignment. There is current debate, however, about the value of such reviews with time-to-event outcomes like PFS. We propose a BICR audit strategy as an alternative to a complete-case BICR to provide assurance of the presence of a treatment effect. We develop an auxiliary-variable estimator of the log-hazard ratio that is more efficient than simply using the audited (i.e., sampled) BICR data for estimation. Our estimator incorporates information from the LE on all the cases and the audited BICR cases, and is an asymptotically unbiased estimator of the log-hazard ratio from BICR. The estimator offers considerable efficiency gains that improve as the correlation between LE and BICR increases. A two-stage auditing strategy is also proposed and evaluated through simulation studies. The method is applied retrospectively to a large oncology trial that had a complete-case BICR, showing the potential for efficiency improvements.

Keywords: Auxiliary variables, Blinded independent central review, Event adjudication committee, Measurement error, Randomized clinical trial, Regression Estimator

1. Introduction

Randomized clinical trials are the gold standard for shaping clinical practice by providing definitive evaluation of treatment efficacy. While overall survival (i.e., time-to-death) is the preferred endpoint in life-threatening diseases, it is not always feasible in some settings. Often, alternative endpoints are potentially subjective and may not be measured consistently. One such endpoint in oncology is progression-free survival (PFS), defined as time to disease progression or death. Disease progression is evaluated radiographically, and is defined as development of new lesions or a greater than 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameters of existing target tumor lesions from the post-randomization nadir value (Eisenhauer et al., 2009). Determination of progression is complicated by many factors, including variability in measuring the size of the target lesions(s), the selection of different target lesions, failure to detect a new lesion, and different interpretations about changes in non-target and nonmeasurable lesions. If disease evaluations are influenced by knowledge of patients’ treatment assignments, estimators of treatment effect may be biased (reader evaluation bias). In a borderline case, for example, a type of reader evaluation bias might occur when the treating (“local”) clinician is more likely to call “progression” earlier amongst patients receiving the control treatment, with the intent of switching the patient’s therapy to one that is (potentially) more effective. Blinded independent central review (BICR) has been advocated to mitigate the potential for biased evaluation of treatment efficacy. BICR typically involves complete retrospective review of all images for all study patients, by readers blinded to treatment assignment. Regulatory agencies have advocated the use of such reviews when PFS is the primary endpoint for drug approval trials (FDA, 2007; EMEA, 2008).

BICR is costly and there is an ongoing debate about the value and use of BICR in oncology (Dodd et al., 2008). One concern is that patient treatment is typically guided by local evaluation (LE). Therefore, progression by LE causes a patient to be withdrawn from the study with no further protocol scans. If BICR does not confirm progression at this last scan then the patient’s data become censored at the time of the last LE. This may result in informative censoring since this patient is more likely to have progression sooner than the remaining at-risk patients. Informative censoring of this type tends to produce a more optimistic PFS curve. In oncology trials with progression-free survival, patients are generally late-stage, and the experimental therapy is hoped to be at least as good as the control. Hence, a concern is that LE is more likely to call progression earlier (than the real time) on the control arm than on the experimental arm, resulting in a biased (LE) estimator of treatment effect that favors the experimental therapy (Dodd et al., 2008). In this case, the BICR-based estimator of treatment effect would have relatively more (informative) censoring in the control arm, resulting in an estimator of treatment effect biased in favor of the control arm. The potential bias in estimating the treatment effect by LE due to reader evaluation bias and the potential bias in the BICR-based estimator due to informative censoring go in opposite directions. Therefore, agreement between BICR and LE estimates provides reassurance about lack of substantive reader evaluation bias.

We propose a BICR-based audit strategy to provide assurance of the LE estimators of treatment effect. The primary goal of the audit is to provide an estimator of the BICR-based hazard ratio when only a subset of patients have BICR of their scans. In the following section, we propose an auxiliary variable estimator of the BICR log-hazard ratio that simultaneously uses LE data and available BICR data. The use of auxiliary population information to improve an estimator based on a sample from the population is a common technique in sample survey methodology (Cochran, 1977; Korn and Graubard, 1999). We provide analytical results describing the efficiency of this method relative to the standard estimator, which uses only BICR audit data, and use these results to develop a two-stage algorithm for auditing. In section 3, the estimator and two-stage algorithm are evaluated via simulation studies. In section 4, we apply the method retrospectively to a large randomized trial in advanced breast cancer. We conclude with a discussion.

2. Methods

We assume an underlying proportional hazards model for the continuous unobserved progression-free survival data. We take as the formal target of inference the true log-hazard ratio of the centrally reviewed data under the given trial conditions (evaluation schedule and censoring pattern).

We assume that the goal of the clinical trial is to demonstrate superiority of an experimental treatment, and that BICR will only be conducted when the LE hazard ratio indicates a clinically meaningful and statistically significant effect in favor of the experimental treatment. The proposed audit is a retrospective sample of m (out of N total) subjects, taken as a simple random sample, for whom BICRs of all images are conducted. The goal of the audit is to provide assurance about the LE-determined treatment effect, through estimation of the true log-hazard ratio under BICR and the corresponding upper bound of a confidence interval for this parameter.

Throughout, let θ̂ denote an estimator of the log-hazard ratio (based on the proportional hazards model). We use the convention that θ < 0 indicates superiority of the experimental therapy. Because we need to identify whether the source of the data is from the audited or non-audited subsets and from the local or central evaluation processes, we use additional subscripts. For example, θ̂L denotes the log-hazard ratio estimator based on PFS times generated from local evaluations, which is further partitioned into θ̂LA and θ̂LĀ to indicate the estimators based on the audited and non-audited subsets, respectively. Likewise, θ̂CA denotes the log-hazard ratio estimator based on PFS times generated under central review amongst the audited subset. We let δ(= m/N) denote the proportion of study participants audited. Because this is a survival-model setting, the number of events determines variances, and the number of events in the audit will be proportional to the sampled audit size. Therefore, we denote the variances of the θ̂LA, θ̂LĀ and θ̂CA as , and VCA, respectively.

2.1 Estimator

The standard estimator based on the sampled data θ̂CA is one estimator of θC, the log-hazard ratio under a BICR with an infinite sample size. We consider a more efficient estimator, which is a linear estimator of the form: θ̄C = θ̂CA − λθ̂LA + λθ̂LĀ, where we select λ to minimize the variance of this estimator. The variance of θ̄C is:

| (1) |

with ρ denoting the correlation between θ̂LA and θ̂CA. This variance is minimized when , which gives

| (2) |

We note here that under asymptotic multivariate normality of θ̂CA, θ̂LA, θ̂LĀ and known ρ, VCA, VL, the maximum likelihood estimator of θC is θ̄C.

If we assume that ρ, VCA and VL are known, then θC is asymptotically unbiased for θC. Specifically, as the trial size N → ∞ (with m/N = δ), the first term in (2) has E(θ̂CA) → θC and the expectation of the second term goes to 0, i.e., E(θ̂LA − θ̂LĀ) → 0. Observe that the weight of second term in (2) depends on the correlation, having greater weight when ρ is higher. When ρ = 0, the estimator is simply θ̂CA. The second term also has greater weight when the variance is relatively higher under the BICR (than LE).

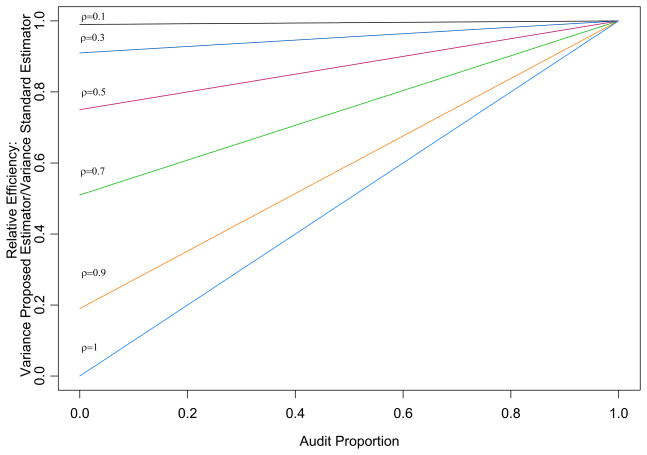

The variance of θ̄C, for known ρ, VCA, and VL, is VCA{1 − ρ2(1 − δ)}. This can be compared to the variance of the estimator θ̂CA, VCA. Figure 1 displays the relative efficiency for θ̄C relative to θ̂CA for different audit sizes and correlations. The relative efficiency of the proposed estimator is greater for higher correlations and smaller audit sizes.

Figure 1.

Efficiency of proposed estimator relative to standard estimator for different audit sizes and correlations.

An estimator of θ̄C can be obtained by substituting θ̂LA, θ̂LĀ, θ̂CA, and the corresponding estimators of the variances and ρ into (2). To obtain an estimator of ρ, we suggest a bootstrap approach. Within the audited subset of size m, m subjects are sampled with replacement. Using both LE- and BICR-determined PFS times, the estimators and are computed. This is repeated B times; the sample correlation coefficient provides the estimator of ρ. Substituting ρ̂, V̂L, and V̂CA gives our estimator:

| (3) |

The estimator (3) requires patient-level data, because of the need to estimate ρ.

2.2 Inference

To obtain a standard error of θ̃C we propose the following variance estimator. First observe that the variance of θ̃C can be written as follows:

Asymptotically, the expectation in (b) is θC, a constant, so that its variance is asymptotically zero. The first term (a) is E[V̂CA{1 − ρ̂2(1 − δ)}]. Hence, a reasonable variance estimator is V̂CA{1 − ρ̂2(1 − δ)}. The properties of this variance estimator are evaluated via simulation studies in section 3.

We propose using the upper bound of a one-sided 95% confidence interval for θC as the basis for providing assurance about the treatment effect. This upper bound can be estimated assuming asymptotic normality of θ̃C, using the proposed variance estimator. Because large effect sizes with an endpoint such as PFS are typically needed to conclude clinical benefit, in some applications, the burden of proof will require stronger evidence than simply ruling out the null hypothesis of no improvement. A more stringent threshold, based on what is considered a minimal relevant improvement in PFS, should be determined. We refer to this threshold as the clinical irrelevance factor (CIF). If the upper bound of the confidence interval for θC is below the CIF, then we conclude that the BICR audit has confirmed the LE findings.

2.3 Determining the audit size and a two-stage testing procedure

Assuming θ̂L is asymptotically normal, and that the LE and BICR results are similar, it is possible to approximate the audit size so that the upper bound of a one-sided (1−α) confidence interval for θC has probability 1 − β of being below the clinical irrelevance factor, denoted γ. For a log-hazard ratio θ̂L, its standard error (based on the complete-case dataset), and known ρ, the corresponding audit size is given as:

| (4) |

where , and Zλ denotes the λ quantile of a normal distribution. To obtain audit sizes less than 1, 2 must be greater than (Z1−α + Z1−β)2. If not, then the effect size may be to small to have power 1 − β even with a complete-case audit. Under a given trial design alternative, one can compute the probability δ is less than some proportion, conditional on a significant LE result. For example, under a design alternative corresponding to one-sided type I error of 0.025 and power of 90%, with the audit one-sided α = 0.05 and power of 90%, P(δ < 0.7|significant LE effect) = 0.50, 0.53, 0.58, 0.69, and 0.83, for ρ = 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, and 0.9, respectively. In practice, an estimate of ρ is required to obtain a δ. A preliminary estimate of ρ can be obtained by performing an initial BICR, using the bootstrap. Let δ0 denote the BICR proportion, based on this initial estimate of ρ. As there is no point in conducting an audit that is almost 100%, in practice we recommend setting a threshold, denoted δ1, for which if δ0 ≥ δ1 a complete-case BICR is conducted.

A two-stage testing procedure is proposed that utilizes the Hochberg procedure to adjust for multiple comparisons (Hochberg, 1988). At the first stage, with audit size δ0, the upper bound of a 1 − α/2 confidence interval is computed. If the bound is below the CIF, the procedure stops and consistency of the treatment effect is concluded. If the result is above the CIF, the audit proceeds to the second stage, which is a complete-case BICR. At the second stage, the upper bound of a 1− α/2 confidence interval on the complete-case BICR is computed; if it is below the CIF, the procedure stops. If the bound is above this threshold, then upper bounds of 1 − α% confidence intervals for both δ0 and the full audit are estimated. If both these bounds fall below the CIF, then consistency of the treatment effect is concluded. If the upper bounds fail to satisfy this criterion, consistency of the treatment effect cannot be concluded. More details about this algorithm are provided in the appendix.

3. Simulations

We conducted several simulation studies to evaluate the proposed auxiliary variable estimator and the two-stage auditing procedure. Although PFS is a combination of progression and death, we focus on the progression time, which was taken to have an underlying exponential distribution. Because progression is measured at intervals, we discretize progression times according to the following process. We assume that for the first year, patients undergo evaluations every six weeks, followed by visits every three months. We further assume that patients undergo evaluations not at their scheduled times, but arrive within a +/− 2 week period of the scheduled visit, using a uniform distribution. The true observed event time is not observed until its following evaluation time. The time of the observed “true” discretized event was then subjected to the errors associated with radiologists’ evaluations. We assume that LE and BICR have a probability of detecting the true event that is a multinomial distribution around the true discretized time. Multinomial probabilities, multi(p−3, p−2, p−1, p0, p1, p2), describe the likelihood of calling a progression around the true event time as follows: p0 describes the probability of calling progression at the true time, while p−3, p−2, and p−1 give probabilities of calling a progression for each of the three evaluation times prior to the event, and p1, p2 give the probability of calling progression for the each of two time points after the true event.

We generate data for 360 patients in each treatment arm, assuming patients are enrolled uniformly over 2 years, with an additional follow-up of 26 weeks after enrollment. The underlying median PFS in the control arm was set to 24 weeks. We consider four different treatment-effect sizes: none, small, moderate and large, corresponding to log-hazard ratios of 0, −0.288, −0.511, and −0.773 (hazard ratios: 1, 0.75, 0.6, 0.46). For each of these, we consider settings with no, small and large reader-evaluation bias. The multinomial probabilities are the same for both treatment arms under the no reader-evaluation bias model for both the local evaluation and BICR. Under scenarios with small and larger reader-evaluation bias, the probabilities in control arm changes (for the local evaluations only) so that progression times are more likely to be called earlier. Table 1 describes the assigned probabilities for each of the simulations presented here. For example, under the scenario with no bias, the probability of calling an event three evaluation times before the true time, p−3, is 2.5% in both treatment arms. Under “large” bias, the probability increases to 10% in the control arm, but remains 2.5% in the experimental arm. In all simulations, the probabilities given to the BICR are specified in the “None” row in table 1. For each scenario, we generated 10,000 data sets. The initial BICR sample to estimate ρ was chosen to ensure about 100 events total. For each effect size, this meant the initial sample was 19%, 20%, 21% and 22%, for the null, small, moderate and large effect sizes, respectively.

Table 1.

Multinomial probabilities describing reader error associated with determining time of progression. Observed event times are shifted according to these probabilities. Local evaluations follow the probabilities described here, while the BICR follow the first row (see text).

| Amount of Differential Reader Bias | Multinomial Probabilities | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Treatment | Experimental Treatment | |||||||||||

| p−3 | p−2 | p−1 | p0 | p1 | p2 | p−3 | p−2 | p−1 | p0 | p1 | p2 | |

| None | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| Small | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| Large | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

Table 2 provides results about the disagreement rates in the time of progression or censoring for the LE and BICR. If the times agreed within a +/− 6 week interval, this was considered an agreement. Without reader bias, the disagreement rates were 32% in the control arm, but range from 32% to 23% in the experimental arm, depending on the effect size. Observe that the disagreement rates differ by treatment arm even without reader-evaluation bias. The disagreement rate decreases in the experimental arm with increasing effect size because more subjects become undergo administrative censoring. For the control arm, with small reader bias, the disagreement rate was 46%, while with large reader bias the disagreement rate was 56%. The correlation between the LE and BICR log-hazard ratios is given in the last column of Table 2, ranging from 0.70 to 0.84.

Table 2.

Summary of average disagreement rates and correlations for simulation scenarios. Agreement is defined as same date of progression or censoring within +/− 6 week interval.

| Reader Bias | Effect Size | Disagreement rate |

ρ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Arm | Experimental Arm | |||

| None | Null | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.84 |

| None | Small | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.84 |

| None | Moderate | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.84 |

| None | Large | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.84 |

| Small | Null | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.76 |

| Small | Small | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.76 |

| Small | Moderate | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.77 |

| Small | Large | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.77 |

| Large | Null | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.70 |

| Large | Small | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Large | Moderate | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.71 |

| Large | Large | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.72 |

To evaluate the properties of the proposed estimator in (3), Table 3 summarizes simulations irrespective of whether the LE results were significant. Results are summarized for the estimators of the log-hazard ratio based on the LE, full BICR, the sample audited BICR data (without the auxiliary variable incorporated) and the proposed auxiliary variable-based estimator. The true log-hazard ratio that generated the continuous event times is presented, along with the approximate asymptotic BICR log-hazard ratio. The true BICR log-hazard was computed empirically by generating 1 million observations per treatment group. Observe that with no reader bias, the estimators of the effect size for all methods are approximately unbiased. Under the audit, however, the auxiliary-variable estimator is approximately twice as efficient as the simple audit estimator (last column). With reader-evaluation bias, the LE results are biased in favor of the experimental therapy. However, because of the impact of informative censoring, the BICR-based log-hazard ratios are biased towards superiority of the control treatment as compared to the true effect size. The proposed variance estimator of θ̃C performs well, as is seen by the agreement of the simulated mean of and the empirical SD of the θ̃C. Finally, note that the standard deviations of the BICR and LE differ slightly, even without reader-evaluation bias. This is because, under the BICR, events are censored when a LE event time is called before the BICR event time. As can be seen in the simulations, this does not cause bias in the estimates of the log-hazard ratios (when there is no reader bias).

Table 3.

Simulation studies of the performance of auxiliary-variable estimator (θ̃C) compared to the local evaluation (LE), a full (complete-case) BICR, and a simple estimator (θ̂CA) based on an audit of 19%, 20%, 21% and 22%, for the null, small, moderate and large, effect sizes, respectively. Average estimates are provided with standard deviations in parenthesis. gives the simulated mean standard errors based on the proposed variance estimator described section 2.2. The true log-hazard ratio is the parameter used to generate continuous event times. The true BICR log-hazard was computed empirically by generating 1 million observations per treatment group.

| Reader Bias | Effect Size | True True log-HR | BICR log-HR | LE Estimator θ̂L (SD) | Full BICR Estimator θ̂C (SD) | Simple BICR Estimator θ̂CA (SD) | Auxiliary-Variable Estimator | Rel. Eff.† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ̃C (SD) | |||||||||

| None | Null | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.000 (0.084) | 0.000 (0.095) | 0.001 (0.222) | 0.000 (0.144) | 0.146 | 2.36 |

| None | Small | −0.288 | −0.287 | −0.283 (0.087) | −0.289 (0.097) | −0.291 (0.203) | −0.289 (0.147) | 0.148 | 1.91 |

| None | Moderate | −0.511 | −0.515 | −0.503 (0.091) | −0.512 (0.101) | −0.514 (0.221) | −0.511 (0.150) | 0.151 | 2.17 |

| None | Large | −0.773 | −0.783 | −0.765 (0.094) | −0.778 (0.106) | −0.782 (0.232) | −0.777 (0.154) | 0.156 | 2.26 |

| Small | Null | 0.000 | 0.232 | −0.122 (0.084) | 0.234 (0.103) | 0.237 (0.231) | 0.239 (0.171) | 0.172 | 1.82 |

| Small | Small | −0.288 | −0.047 | −0.400 (0.086) | −0.048 (0.105) | −0.049 (0.210) | −0.046 (0.176) | 0.176 | 1.43 |

| Small | Moderate | −0.511 | −0.265 | −0.615 (0.090) | −0.267 (0.110) | −0.268 (0.241) | −0.264 (0.177) | 0.178 | 1.85 |

| Small | Large | −0.773 | −0.522 | −0.871 (0.095) | −0.527 (0.115) | −0.532 (0.246) | −0.525 (0.182) | 0.182 | 1.84 |

| Large | Null | 0.000 | 0.421 | −0.194 (0.083) | 0.418 (0.112) | 0.422 (0.257) | 0.425 (0.207) | 0.201 | 1.55 |

| Large | Small | −0.288 | 0.189 | −0.467 (0.087) | 0.140 (0.115) | 0.139 (0.236) | 0.146 (0.200) | 0.200 | 1.39 |

| Large | Moderate | −0.511 | −0.078 | −0.681 (0.089) | −0.076 (0.117) | −0.078 (0.259) | −0.071 (0.200) | 0.201 | 1.67 |

| Large | Large | −0.773 | −0.331 | −0.935 (0.094) | −0.330 (0.119) | −0.327 (0.264) | −0.324 (0.203) | 0.204 | 1.69 |

Relative Efficiency=SD(θ̂C)2/SD(θ̃C)2

Table 4 summarizes results from the two-stage audit approach, comparing it to a full BICR. We set δ1=0.7. The proportion of LE results that reject the null hypothesis H0: θ ≥ 0, used a one-sided 0.025 level test. Because the BICR is not prompted unless the LE result is significant, for the full BICR and the proposed two-stage BICR strategy, we report the proportion of times both the LE and the BICR results reject H0: θ ≥ 0. For a full BICR, α = 0.05, one-sided. We applied the Hochberg procedure as described in section 2.3, with α = 0.05. As expected, under the null hypothesis (θ = 0), with “small” and “large” amounts of reader bias, the type I error for the LE is inflated considerably; rejection rates are 31% and 65% for these two scenarios, respectively. However, under a full BICR and the two-stage audit strategy, the overall rejection rates are conservative. Indeed, the full BICR and the BICR audit never reject the null hypothesis in these cases. This is because informative censoring, which occurs when an early progression call by LE cannot be confirmed by BICR, biases BICR estimators towards superiority of the control treatment. The resulting reduction in power from this bias towards the null hypothesis (under BICR) is also observed. Finally, note the slight loss in power of the BICR audit relative to the full BICR in two scenarios (in the small bias and moderate effect size setting; and in the large bias and large effect size setting). Under the large reader bias and large effect size setting, the full BICR rejected 86% of the time, while the audit procedure rejected 81% of the time. This is the cost of the two-stage procedure selected for these simulations. A more stringent α-level may be preferred for the initial audit, which would reduce power loss, but increase the audit size.

Table 4.

Summary of simulation studies of two-stage auditing strategy. LE is local evaluation. Full BICR is a complete-case blinded independent central review. BICR two-stage audit is the proposed audit strategy.

| Reader Bias | Effect Size | LE: Proportion Null Rejected (proportion of times BICR conducted) | Full BICR: Proportion Conclude: “Treatment Effect” | BICR two-stage Audit: Proportion Conclude: “Treatment Effect” | Final Audit Size, When Conducted Percentiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 50th | 90th | |||||

| None | Null | 0.023 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| None | Small | 0.907 | 0.871 | 0.871 | 0.245 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| None | Moderate | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.995 | 0.210 | 0.210 | 0.355 |

| None | Large | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.220 | 0.220 | 0.220 |

| Small | Null | 0.309 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Small | Small | 0.996 | 0.114 | 0.101 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Small | Moderate | 1.000 | 0.793 | 0.725 | 0.210 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Small | Large | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.220 | 0.220 | 1.000 |

| Large | Null | 0.645 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Large | Small | 1.000 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Large | Moderate | 1.000 | 0.160 | 0.138 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Large | Large | 1.000 | 0.860 | 0.809 | 0.220 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

4. Application: E2100

We apply the methods above retrospectively to E2100, an open-label, randomized phase III trial in metastatic breast cancer (Miller et al., 2007). The trial randomized 722 women to paclitaxel or paclitaxel plus be-vacizumab, with a progression-free survival primary endpoint. A retrospective, complete-case BICR was conducted and the log-hazard ratios for LE and BICR were similar: −0.724 (95% CI −0.914 to −0.534) for LE, and −0.608 (95% CI −.820 to −0.396) for BICR. We apply the auxiliary-variable estimator with and without the two-stage approach to this dataset. For simplicity, the analyses ignore stratification factors, but results are similar (Gray et al., 2009). In practice, one might want to implement the audit with stratification according to important factors. Because we had a complete-case BICR, we applied the audit process repeatedly (10,000 times). The estimators θ̃C and θ̂CA with a 25% audit produced average estimates of θ̃C = −0.611 (average : 0.174) and θ̂CA = −0.613 (average : 0.209), showing the efficiency benefits of using the auxiliary variable approach.

Table 5 describes results using the two-stage approach. An initial audit of 25% was chosen to ensure 100 events in the initial sample BICR. The formula (4) was then used to select the audit size specifying clinical irrelevance factors (CIFs) of 0 and log(0.9), log(0.8), and log(0.7). For these four cases, the two-stage approach provided assurance of the LE estimate of treatment effect. The average audit sizes were 28%, 34%, 54% and 80% for CIFs of 0, log(0.9), log(0.8), and log(0.7), respectively. The 99th percentile of the 95% CI upper bound for the log hazard ratio is shown to give a sense of how precisely the upper bound is estimated relative to the CIF.

Table 5.

Application of two-stage strategy to Phase III trial in metastatic breast cancer for clinical irrelevance factors (CIFs). Confidence intervals were computed using the Hochberg procedure described in section 2.3, with an overall one-sided α = 0.05.

| CIF | 99th percentile of CI Upper Bound | Average Audit Size |

|---|---|---|

| log(1.0)= 0 | −0.016 | 0.28 |

| log(0.9)=−0.11 | −0.112 | 0.37 |

| log(0.8)=−0.22 | −0.227 | 0.54 |

| log(0.7)=−0.36 | −0.358 | 0.80 |

5. Discussion

Our proposed audit strategy is based on estimating the expected value of the BICR log-hazard ratio (with an infinite sample size), and not the log-hazard ratio that would be observed from a complete BICR. In particular, as the audit size increases to include the entire study sample, the standard error of the estimated log-hazard ratio should not converge to zero. Rather, it should converge to the standard error of the log hazard ratio that would be observed for a complete BICR. This type of audit is distinct from a typical accounting audit, where a complete audit would yield standard errors of zero.

The auxiliary variable estimator we have proposed is known as a “regression estimator” in the classical sample survey and auditing literature (Kaplan, 1973; Cochran, 1977). Regression estimators use the individual-level audited data to calculate the required correlation coefficient between the primary-variable estimator and the auxiliary-variable estimator. In our context, we have used the bootstrap to estimate the correlation between the primary-variable (BICR) hazard-ratio estimator and the auxiliary-variable (LE) hazard-ratio estimator, but in the simpler classical setting of estimating means or totals, the Pearson correlation of the primary and the auxiliary data would be used.

There are two types of data that could be considered missing in auditing applications with survival data: data not available because the case was not selected for the audit and data excluded due to censoring at the last time of observation. For a number of reasons, including regulatory reasons, the current standard in clinical trials with a PFS endpoint is a 100% central review audit and analysis based solely on the primary-variable audited data. That is, there is no attempt to improve efficiency by imputing the censored data using the auxiliary data. Our regression estimator, which reduces to the primary-variable estimator with a 100% audit, improves efficiency without attempting to impute for censored data. Auxiliary variable estimators that improve inference for proportional-hazards model parameters of censored primary-variable survival data have been developed (Pepe et al., 1994; Robins and Finkelstein, 2000; Hsu et al., 2006; Lu and Tsiatis, 2008). These estimators may provide efficiency gains beyond our estimator. However, such additional efficiency gains will invariably depend on the appropriateness of the assumptions made. Finally, we note that stratified sampling (by event status) may result in efficiency gains. These are all areas of future research.

An alternative target of inference is the difference in the expected values of the complete BICR log-hazard ratio and the LE log-hazard ratio. One could estimate this target by calculating the difference between the simple BICR log-hazard-ratio on the audited sample (no need for the auxiliary variable estimator) and the LE log hazard ratio; the standard error of this difference could be estimated by a bootstrap. However, this alternative target does not take into account how large the treatment effect is, which is relevant in deciding whether the differences in hazard ratios are clinically important. For example, the same size LE-BICR difference in log hazard ratios may be cause for concern with a moderate treatment effect but not important with a large treatment effect. We believe estimation of the BICR hazard ratio, and comparing it to the clinical irrelevance factor provides a better answer to the clinical question of interest.

In our analyses we assumed that a patient’s BICR data is censored at the time of progression by LE, if the BICR does not confirm the progression and there are no later scans available for BICR. A later death time may be available for some of these patients, suggesting possible incorporation of these death times into the analysis. This issue is not restricted to the auditing context, as death times may frequently be available for patients who are lost to (progression) follow-up. In the general context, the US Food and Drug Administration has suggested, as a sensitivity analysis, considering a death that occurs after a patient is lost-to-follow-up as a PFS event, provided it occurs within less than two regularly scheduled assessment times (FDA, 2007). Alternatively, modeling assumptions can be used to incorporate into the analysis death times that occur after patients are lost to follow-up (Ruan and Gray, 2008). These same approaches could be considered in the auditing context. Issues related to measurement error in PFS assessments are also important, and are discussed in Korn et al. (2010).

In summary, we propose a retrospective BICR audit of images from a subset of patients as a means for providing reassurance (or the lack thereof) in locally-determined estimator of treatment effect, in settings in which the LE estimates are both statistically significant and clinically meaningful. The retrospective approach requires the ability to ultimately access all images collected in a trial, when the decision to proceed to a complete BICR is made. To improve efficiency, we develop an estimator of the log-hazard ratio that incorporates auxiliary variable information from the LE, and a two-stage audit approach. After one gains experience with this procedure in certain settings, it is possible that typical values of ρ may be used to estimate audit size, rather than performing the initial sample to estimate ρ. This is an area of future research.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Editor, Associate Editor and two reviewers for their helpful comments. This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. (http://biowulf.nih.gov).

7. Appendix: Two-stage procedure algorithm

We denote the standardized difference as Δ̂.

If Δ̂ > Z1−α + Z1−β, proceed with steps below. Otherwise, proceed to complete-case BICR. An alternative strategy, under the latter situation is to consider a larger β for which Δ̂ exceeds Z1−α + Z1−β and determine whether an audit is worth considering for that power.

Perform an initial BICR on a random sample of proportion δ0.

Bootstrap LE and BICR results to estimate ρ.

Substitute ρ̂ into equation (4) and estimate the audit size, δ.

-

If δ ≤ δ0, the size of the initial sample (to estimate ρ) was sufficiently large for the audit. Hence, the estimator θ̃C and the upper bound of its (1 − α/2)% confidence interval are computed.

If the upper bound is below the CIF, stop and conclude that consistency of a treatment effect has been appropriately verified.

-

If the upper bound is not below the CIF, continue to a full-sample BICR to estimate θC and the upper bound of its (1 − α/2)% confidence interval.

If this upper bound is below the CIF, stop and conclude that consistency of a treatment effect has been appropriately verified.

If this upper bound is not below the CIF, compute upper bounds for both the initial audit and the full BICR using a (1 − α)% confidence interval for each. If both of these upper bounds are below the CIF, conclude that consistency of a treatment effect has been appropriately verified.

If δ ∈ (δ0, δ1], audit an additional proportion δ − δ0 and estimate θ̃C along with the upper bound of its (1 − α/2)% confidence interval. Repeat steps (5a) – (5c).

-

If δ > δ1, proceed to a full audit to estimate θ̃C along with the upper bound of its (1 − α/2)% confidence interval.

If the upper bound is below the CIF, conclude that consistency of a treatment effect has been appropriately verified.

If the upper bound is not below the CIF, compute upper bounds for both the initial audit and the full BICR using a (1 − α)% confidence interval for each. If both of these upper bounds are below the CIF, conclude that consistency of a treatment effect has been appropriately verified.

References

- Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 3. John. Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 1977. pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd LE, Korn EL, Freidlin B, Jaffe CC, Rubinstein LV, Dancey J, Mooney MM. Blinded independent central review of progression-free survival in phase III clinical trials: important design element or unnecessary expense? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:3791–3796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubenstein L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMEA. Methodological considerations for using progression-free survival (PFS) as primary endpoint in confirmatory trials for registration. 2008 http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/2799408en.pdf.

- FDA. Guidance for industry clinical trial endpoints for the approval of cancer drugs and biologics. 2007 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM071590.pdf.

- Gray R, Bhattacharya S, Bowden C, Miller K, Comis RL. Independent review of E2100: a phase III trial of bevacizumab plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel in women with metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:4966–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C, Taylor JMG, Murray S. Survival analysis using auxiliary variables via non-parametric multiple imputation. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:769–781. doi: 10.1002/sim.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RS. Statistical sampling in auditing with auxiliary information estimators. Journal of Accounting Research. 1973;11:238–258. [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1999. pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Dodd LE, Friedlin B. Measurement error in survival analysis in RCTs. Clinical Trials. 2010;7:625–633. doi: 10.1177/1740774510382801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Tsiatis AA. Improving the efficiency of the log-rank test using auxiliary covariates. Biometrika. 2008;95:679–694. [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, Dickler M, Cobleigh M, Perez EA, Shenkier T, Cella D, Davidson NE. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:2666–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Reilly M, Fleming TR. Auxiliary Outcome Data and the Mean Score Method. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 1994;42:137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Robins J, Finkelstein D. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS clinical trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]