Abstract

AIM: To compare the mid-term outcomes of laparoscopic calibrated Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication with Dor fundoplication performed after Heller myotomy for oesophageal achalasia.

METHODS: Fifty-six patients (26 men, 30 women; mean age 42.8 ± 14.7 years) presenting for minimally invasive surgery for oesophageal achalasia, were enrolled. All patients underwent laparoscopic Heller myotomy followed by a 180° anterior partial fundoplication in 30 cases (group 1) and calibrated Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication in 26 (group 2). Intraoperative endoscopy and manometry were used to calibrate the myotomy and fundoplication. A 6-mo follow-up period with symptomatic evaluation and barium swallow was undertaken. One and two years after surgery, the patients underwent symptom questionnaires, endoscopy, oesophageal manometry and 24 h oesophago-gastric pH monitoring.

RESULTS: At the 2-year follow-up, no significant difference in the median symptom score was observed between the 2 groups (P = 0.66; Mann-Whitney U-test). The median percentage time with oesophageal pH < 4 was significantly higher in the Dor group compared to the Nissen-Rossetti group (2; range 0.8-10 vs 0.35; range 0-2) (P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U-test).

CONCLUSION: Laparoscopic Dor and calibrated Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication achieved similar results in the resolution of dysphagia. Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication seems to be more effective in suppressing oesophageal acid exposure.

Keywords: Achalasia, Dor fundoplication, Dysphagia, Gastroesophageal reflux, Laparoscopy, Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication

INTRODUCTION

Oesophageal achalasia is the best understood and best characterised oesophageal motility disorder[1]. Of unknown aetiology, it is a functional disease secondary to irreversible degeneration of oesophageal myenteric plexus neurons causing aperistalsis or uncoordinated contractions of the oesophageal body and incomplete or absent post-deglutitive relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES)[2,3]. All the available treatments for achalasia are palliative, being directed toward elimination of the outflow resistance caused by abnormal LES function and aiming to improve the symptoms related to oesophageal stasis, such as dysphagia and regurgitation[4,5].

According to the literature, surgical therapy, relying on an oesophago-gastric extramucosal myotomy with fundoplication, seems the treatment of choice for achalasia, being more effective in improving symptoms than both endoscopic pneumatic dilation and endoscopic botulinum toxin injection into the LES, especially in the long-term[6-11]. Furthermore, the advent of laparoscopic techniques has rekindled interest in the surgical management of this disease, decreasing the morbidity associated with thoracotomic or laparotomic myotomy which for several years indicated that endoscopic pneumatic dilation was the first line therapy for oesophageal achalasia[3].

However, many issues regarding the surgical technique are still debated such as the length of myotomy, the association of an anti-reflux procedure with myotomy and the type of fundoplication to perform. Concerning the latter question, both a 180° anterior and 270° posterior partial fundoplication represent the most frequently performed anti-reflux procedures after myotomy.

Although the total 360° wrap is generally considered an obstacle to normal oesophago-gastric transit in the presence of defective peristaltic activity, some authors showed that the Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication is not an obstacle to oesophageal emptying after Heller myotomy, achieving excellent results in terms of dysphagia and providing total protection from gastroesophageal reflux (GER)[10].

The present study aimed to compare the surgical and mid-term outcomes of laparoscopic calibrated Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication with laparoscopic Dor fundoplication, performed after oesophago-gastric myotomy, for the treatment of oesophageal achalasia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients referred between September 2002 and March 2007 for primary oesophageal achalasia were inserted in a prospective database including the results of symptoms evaluation and of oesophageal instrumental studies. Using this database, the results of fifty-six patients (26 men, 30 women; mean age 42.8 ± 14.7), who had undergone minimally invasive surgical treatment, were analyzed in this study.

All patients enrolled in this study were between 16 and 70 years old, had a preference for surgical treatment and had no absolute contraindications for laparoscopic surgery.

We excluded patients with central nervous system diseases, mental disorders, connective system diseases, diabetes mellitus, neoplastic diseases, inflammatory bowel diseases, pregnancy, previous gastro-intestinal diseases and those who were on medications that may have influenced gastric acidity or motility. Patients presenting with achalasia associated with other oesophageal diseases were also excluded. In the same way, patients who had undergone previous surgical treatment for achalasia and who had previous oesophageal, gastric or biliary surgery were excluded.

Preoperative evaluation of the patients was performed using symptom questionnaires (composite symptom score combining severity and frequency of symptoms[12] and SF-36 questionnaire[13,14]), barium swallow, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and stationary oesophageal manometry.

All enrolled patients underwent laparoscopic extramucosal Heller myotomy associated with an anti-reflux procedure.

Depending on the type of fundoplication performed after myotomy, the study was divided in two periods: during the first 2 years (from April 2003 to April 2005), the authors performed a total calibrated (Nissen-Rossetti) fundoplication, and from May 2005 to May 2007 they performed an anterior 180° (Dor) fundoplication. A 6-mo follow-up period with symptomatic evaluation and barium swallow was undertaken. Twelve and twenty-four months after surgery, all patients were invited to repeat the symptomatic evaluation and were interviewed about the persistence of preoperative symptoms and about the presence of symptoms related to the GER disease (GERD) (heartburn, acid regurgitation and atypical symptoms).

Data regarding symptoms and patients’ general health (GH) were collected via the same questionnaires used for the preoperative evaluation. Furthermore, at the same follow-up points (12 and 24 mo), each patient was asked to undergo barium swallow, endoscopy, oesophageal manometry and 24 h oesophago-gastric pH monitoring, to evaluate any abnormal GER, as part of the study protocol.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Second University of Naples and conducted according to the ethical standards of the Helsinki declaration.

Each patient gave informed written consent.

Symptoms and quality of life

A composite symptom score, combining severity and frequency of dysphagia, regurgitation and chest pain, was used to evaluate patients’ symptoms, the range varying from 0 (no symptoms) to 33 (maximum symptoms)[12].

Quality of life (QoL) was evaluated by means of the SF-36 questionnaire[14], which measures eight domains of health-related quality of life (HRQL) using 36 items. These include physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, emotional role, GH, social functioning, mental health and vitality. The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with low scores representing poorer HRQL and a score of 100 representing the best possible HRQL.

Barium swallow

In all patients a standard oesophageal radiological examination after swallowing a bolus of contrast (Prontobario HD-Bracco, Milan, Italy) was obtained before surgery and at 6, 12 and 24 mo follow-up.

The presence of hold-up in the lower two-thirds of the oesophagus, bird-beak appearance, scarce and slow oesophageal body clearance and dilated and atonic oesophagus were considered suggestive of achalasia.

The maximum oesophageal diameter was measured in the antero-posterior projection at the site of the barium-air level and was recorded to grade the severity of achalasia as follows: stage I < 4 cm; stage II 4-6 cm; stage III > 6 cm; stage IV, any diameter with sigmoid morphologic appearance of the oesophagus[10].

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Endoscopy was performed in all patients to rule out any malignancies before surgery and, 1 and 2 years after surgery, to evaluate the presence of reflux oesophagitis or stenosis.

The presence of atonic and dilated oesophageal body, food stagnation in the oesophagus, spastic oesophago-gastric junction (EGJ) and difficult crossing through the EGJ in the absence of any malignancies were considered suggestive of achalasia. The presence of oesophagitis was graded according to the Los Angeles classification[15].

Oesophageal manometry

All subjects underwent stationary oesophageal manometry with an eight channel, multiple-lumen catheter (4 open tips at the same level and oriented radially at 90° intervals and the other 4 extending proximally at 5 cm intervals) (Menfis Biomedica Inc. Bologna, Italy), perfused with a pneumo-hydraulic capillary infusion system (Menfis Biomedica Inc., Bologna, Italy).

Each channel was connected to an external pressure transducer (Menfis Biomedica Inc. Bologna, Italy) and the electric signal was sent to an acquisition/amplification module that subsequently directed the processed signal to a digital system for data acquisition, storing and analysis.

Each manometric evaluation was performed in all patients after 12-h fasting and after discontinuation of all medication affecting the gastroesophageal tract for at least 1 wk.

The catheter was passed through the nose until all the channels were placed into the stomach. The gastric pressure at the end of expiration was recorded and used as a reference point. If the catheter did not pass the EGJ, a guidewire placed in the stomach during endoscopy was used.

Manometric evaluation of the LES and of the neo-sphincter was performed using the stationary and motorized pull-through techniques, according to Gruppo Italiano Studio Motilità Apparato Digerente guidelines[16]. The parameters used for LES and neo-sphincter evaluation were resting pressure, total length and percentage of post-deglutitive relaxation.

Oesophageal motor activity (amplitude and duration of waves, percentage of peristaltic and simultaneous post-deglutitive sequences) was evaluated with stationary pull-through after 20 dry swallows.

Incomplete relaxation of the LES and aperistalsis of the oesophageal body (characterised either by simultaneous oesophageal contractions or no apparent contractions) were the manometric diagnostic criteria for achalasia[1].

Twenty-four-hour oesophago-gastric pH monitoring

At 12 and 24-mo follow-up, following manometric evaluation, 24-h ambulatory combined oesophageal and gastric pH monitoring was performed. Two glass pH catheters (Telemedicine s.r.l., Naples, Italy) were passed through the nose, positioning the proximal pH sensor 5 cm above the upper border of the LES, defined by previous oesophageal manometry. The distal pH sensor was located in the stomach, 5 cm distal to the lower border of the LES. Before each study, the pH probes were calibrated in buffer solutions of pH 7 and 1. The patients were instructed to remain in an upright or seated position during the daytime, to take three meals and to keep a diary of food intake, symptoms, and the time of the supine and upright position.

The data were registered and stored on a portable digital recorder (Menfis Biomedica Inc. Bologna, Italy) for 24 h and then the sensors were removed and the data downloaded into a personal computer for analysis. Gastroesophageal acid reflux was defined as a drop in oesophageal pH below 4.

Number of reflux episodes (normal value < 50), number of reflux episodes longer than 5 min (normal value < 3.1), percentage of total, upright and supine time with intraesophageal pH < 4 (normal values < 4.2%, < 6.3%, < 1.2%, respectively), longest reflux episode (normal value < 9.2 min) and DeMeester score (normal value < 17.92), were the parameters used for computerized analysis of acid reflux[17].

Operative technique

All patients were operated using the same technique and by the same surgeon.

Briefly, surgery was performed using a five-port technique with 4 trocars of 10 mm in diameter and 1 of 5 mm. Pneumoperitoneum at 12 mmHg was induced through the open laparoscopy technique. The patient was placed in a 20° reverse-Trendelemburg position.

The surgeon was placed between the patient’s legs, an assistant on the right side of the patient and another assistant on the left side. With the left hepatic lobe raised, using a grasper and a vessel-sealing system (Ligasure1100 Atlas™ 10 mm; Valleylab/Tyco Healthcare UK Ltd.) the Laimer-Bertelli membrane was divided to expose the diaphragmatic pillars and the oesophageal anterior wall. When a Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication was performed, a wide dissection of the diaphragmatic crus was carried out to achieve a window, at least 5 cm in length, behind the lower oesophagus. Thus, the right diaphragmatic pillar was dissected from top to bottom exposing the deep portion of the left pillar that was subsequently dissected from bottom to top achieving a wide mobilization of the oesophagus on its lower mediastinal and abdominal portion. During dissection, the anterior and posterior vagus nerves were identified and preserved. Subsequently, after identification of the squamo-columnar junction (SCJ) by means of the endoscope, an oesophago-gastric myotomy, 5-6 cm long, extending 3-3.5 cm on the gastric side and 2-2.5 cm on the oesophageal tract, was performed. The anterior 180° fundoplication was performed with three non-absorbable stitches on each side suturing the gastric wall to the edge of the myotomy.

Total fundoplication was performed with two non-absorbable stitches, using the anterior wall of the gastric fundus, not incorporating the anterior wall of the oesophagus.

In each case, division of the short gastric vessels was not necessary. During the surgical procedures, the myotomy and the fundoplication were calibrated through endoscopy and manometry, by means of the same instruments used for patients’ preoperative evaluation. In particular, the endoscope was inserted transorally at the beginning of the surgical procedure. Identification of the SCJ, using the transillumination properties of the endoscope, facilitated dissection of the lower oesophagus and guided extension of the myotomy.

At endoscopy, the myotomy was considered adequate if no mucosal tears were found and when the appearance of a complete opening of the EGJ was achieved. Intraoperative manometry was performed placing the catheter in the stomach by means of a guidewire. The myotomy was considered adequate if a residual LES resting pressure less than 4 mmHg was registered[10].

With regard to the endoscopic and manometric calibration of the oesophageal wrap, the fundoplication was considered inadequate (too tight, misplaced or asymmetric) when a difficult transit of the endoscope through the wrap occurred, when the position of the wrap in relation to the SCJ was not correct (less than 1 cm above the SCJ), the internal aspect of the wrap seemed irregular and interrupted on the retroversion views and when the neo-sphincter resting pressure exceeded 40 mmHg[10]. According to intraoperative endoscopy and manometry, whenever the fundoplication was not effectively calibrated, the surgeon refashioned it correctly.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the programs InStat Graph-Pad Prism® 5 and Graph-Pad StatMate® (San Diego, California, USA). Values are expressed as mean ± SD or medians (25th, 75th percentiles, range). Continuous data were compared between each group using the Unpaired t-test, the Paired t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test, when indicated, according to distribution. Prevalence data were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test. A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The primary end point of the study was the incidence of pathological clinical and instrumental GER in the Heller plus Dor, and Heller plus Nissen-Rossetti groups. Secondary end points included symptom score and dysphagia recurrence rate, QoL and postoperative neo-sphincter pressure at oesophageal manometry. Outcome variables were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.

RESULTS

Of the 56 patients who underwent laparoscopic Heller myotomy, 30 (14 men, 16 women; mean age 42.4 ± 14.3) received an anterior 180° partial fundoplication and 26 (12 men, 14 women; mean age 43.3 ± 15.4) received a Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication. Table 1 shows the preoperative characteristics of the two groups of patients.

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics of the 2 patient groups

| Features | Total fundoplication | Partial fundoplication | P-value |

| Sex | 12 M; 14 F | 14 M; 16 F | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 42.4 ± 14.3 | 43.3 ± 15.4 | 0.821 |

| Weight (kg, mean ± SD) | 71 ± 7.7 | 70.3 ± 7.14 | 0.711 |

| Previous pneumatic dilation | 2 | 2 | |

| Previous botulinum toxin injection | 1 | 1 | |

| Duration of symptoms (mo), median (interquartile range) | 7.5 (3.7-15.7) | 7.5 (4.7-27.7) | 0.432 |

Unpaired t-test;

Mann-Whitney U-test. M: Male; F: Female.

There were not significant differences in age, gender, weight distribution and duration of symptoms between the two groups.

Four patients, 2 in the total and 2 in the anterior fundoplication group, had undergone previous pneumatic dilation of the cardia, whereas 2 patients (1 in the Dor group and 1 in the Nissen-Rossetti group) had undergone endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin into the LES before surgery.

Preoperative assessment

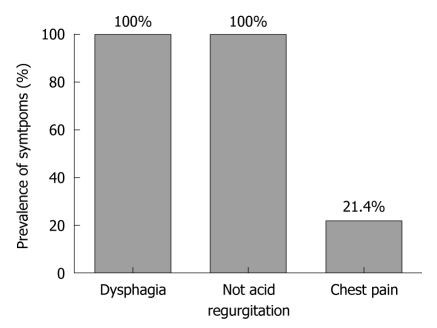

All patients had dysphagia and no acid regurgitation, whereas 12 patients (21.4%) reported chest pain (Figure 1). Median symptom score was 22.5 (range 12-33) [21 (range 12-33) in the Dor group and 23 (range 12-33) in the Nissen-Rossetti group (P = 0.40; Mann Whitney U-test)]. At oesophagogram, the median of the maximum oesophageal diameter was 4.75 cm (range 3.5-10 cm).

Figure 1.

Preoperative symptoms. Prevalence of dysphagia, regurgitation and heartburn in patients enrolled in the study.

Based on the results of barium oesophagogram, achalasia severity was stage I in 18 (32.14%) patients (10 in the Dor group and 8 in the Nissen-Rossetti group), stage II in 24 (42.8%) patients (14 in the Dor group and 10 in the Nissen-Rossetti group), stage III in 10 (17.8%) patients (4 in the Dor group and 6 in the Nissen-Rossetti group) and stage IV in 4 (7.1%) patients (3 in the Dor group and 1 in the Nissen-Rossetti group).

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed, in all cases, an atonic and dilated oesophageal body and a spastic EGJ, whereas grade A oesophagitis was found in 7 patients (12.2%).

At manometry, simultaneous oesophageal contractions were found in 20 patients (35.7%), whereas in 36 cases (64.2%) no apparent contractions of the oesophageal body were recorded. Evaluation of the LES showed incomplete relaxations in all patients. Median LES-P was 22 mmHg (interquartile range 15-30).

The prevalence of symptoms, the presence of oesophagitis, and the manometric and radiological features did not differ significantly between the 2 groups of patients.

Surgery and early postoperative outcome

All surgical procedures were completed laparoscopically. No mortality was observed. Table 2 shows the results of surgery and early postoperative outcome.

Table 2.

Surgical and early postoperative outcome in the 2 patient groups

| Variables | Total fundoplication | Partial fundoplication | P-value |

| Median operating time (min), median (range) | 90 (75-100) | 90 (75-150) | 0.021 |

| Major intraoperative complications | 1 | 1 | |

| Minor intraoperative complications | 0 | 2 | |

| Lower oesophageal sphincter pressure (mean ± SD) | 29.38 ± 0.5 | 24.1 ± 0.5 | 0.0012 |

| Postoperative complications | 1 | 2 | |

| Transfusions | 0 | 0 |

Mann-Whitney U-test;

Unpaired t-test.

Median duration of surgery was 90 min (range, 75-100 min) in the Dor group and 90 min (range 75-150 min) in the Nissen-Rossetti group (P = 0.67; Mann-Whitney U-test).

One major intraoperative complication was observed both in the Dor and Nissen-Rossetti group.

In the first case, an intraoperative mucosal tear occurred and was immediately repaired by placing 1 stitch and abdominal drainage. The other patient developed an intraoperative pneumothorax which required thoracic drainage. In another two patients in the Dor group, a minor intraoperative complication occurred, represented by an episode of intraoperative cervical subcutaneous emphysema. Blood transfusions were not required in any of the patients. The myotomy and fundoplication were calibrated by intraoperative endoscopy and manometry in both groups. In each case, residual LES pressure lower than 4 mmHg after myotomy, as measured by intraoperative manometry, was considered satisfactory.

The intraoperative median resting pressure of the new valve was significantly higher in the Nissen-Rossetti group, compared with the Dor group [29 (range 25-32) in the Nissen-Rossetti and 22.5 (range 20-29) in the Dor group (P < 0.001; Mann Whitney U-test)].

In the early postoperative period, two patients in the Dor group developed pulmonary atelectasis, promptly resolved with conservative treatment, and one patient in the Nissen-Rossetti group had urinary retention.

Median hospital stay was 3 d (range 2-7 d) in the Nissen group and 3 d (range 2-7 d) in the Dor group, no significant differences between the groups were observed (P = 0.81; Mann-Whitney U-test).

Follow-up assessment

Follow-up data were available for all patients at 6 and 12 mo follow-up, whereas, at 24 mo follow-up, the clinical and instrumental data of two patients with a Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication were missing.

These two patients showed a good outcome at 6 and 12 mo, and although they underwent symptomatic evaluation at 24 mo follow-up, they rejected invasive investigations (endoscopy, manometry and pH-metry).

Consequently, 24 mo after surgery, complete instrumental data were available for 54 patients (96.4%), and based on the intention-to-treat analysis, the patients without 24-h oesophago-gastric pH monitoring were considered not to show pathological GER.

At 24 mo follow-up, 4 patients in the Dor group (4/30 = 13.3%) reported heartburn and acid regurgitation, whereas no patients in the Nissen-Rossetti group had GERD symptoms (P = 0.11; Fisher’s exact test).

Four patients (2 with stage IV and 2 with stage III achalasia) (4/56 = 7.1%) had moderate and occasional dysphagia; of these patients, 2 received a Nissen-Rossetti (2/26 = 7.7%) and 2 a Dor fundoplication (2/30 = 6.6%) (P = 1.00; Fisher’s exact test).

The postoperative median symptom score decreased from 21 (range 12-33) to 3 (range 3-12) in the Dor group (P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U-test) and from 23 (range 12-33) to 3 (range 3-12) in the Nissen-Rossetti group (P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U-test), without any significant difference between the 2 groups.

In particular, the median dysphagia score did not differ significantly between the 2 groups [3 (range 0-5) in the Nissen-Rossetti group and 3 (range 0-5) in the Dor group (P = 0.91; Mann Whitney U-test)].

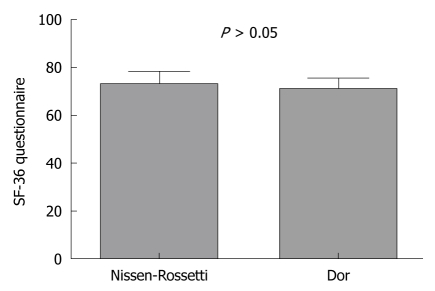

Although the total mean health-related QoL score was significantly higher than the preoperative score (83.6 ± 4.2 vs 71.3 ± 4.7: P < 0.0001; paired t-test), there was no significant difference in the QoL between the patients with Dor and Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication (70.5 ± 4.06 vs 72.3 ± 45.3: P = 0.16; unpaired t-test) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quality of life at 24 mo follow-up. Postoperative Qol (as measured by the SF-36 questionnaire) in patients with a partial anterior fundoplication and with a total fundoplication (P > 0.05; unpaired t-test).

At radiological examination, none of the patients showed hold-up in the lower two-thirds of the oesophagus or bird-beak appearance.

Furthermore, the median of the maximum oesophageal diameter decreased from 4.75 (range 3.5-10) to 4 (range 3-10) (P = 0.01; Mann-Whitney U-test), with no significant differences between the Nissen-Rossetti and Dor groups (P = 0.93; Mann-Whitney U-test).

Two years after surgery, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed grade A-B oesophagitis in 3 patients in the Dor group who did not show oesophagitis preoperatively. Normal endoscopic features were found in all other patients.

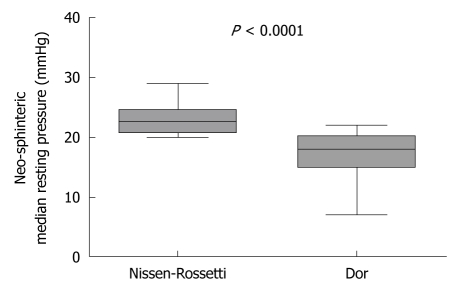

At manometry, the median neo-sphincter resting pressure in the Nissen-Rossetti group was significantly higher than that in patients with Dor fundoplication [22.5 (range 20-29) in the Nissen-Rossetti vs 18 (range 7-22) in the Dor group (P = 0.91; Mann Whitney U-test)] (Figure 3). In all cases, the neo-sphincter showed a complete post-deglutitive relaxation.

Figure 3.

Postoperative oesophageal manometry. Neo-sphinteric median resting pressure in patients with a Dor and with a Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication (P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U-test).

Manometric evaluation in 8 patients with stage II achalasia, 4 in the Dor group (4/30 = 13.3%) and 4 in the Nissen-Rossetti group (4/24 = 16.6%), showed complete peristaltic contractions of the oesophageal body in 35.6% of dry swallows.

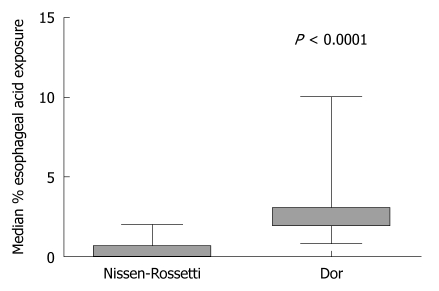

At pH-metry, 4 patients with an anterior fundoplication (4/30 = 13.3%) showed pathological acid reflux, whereas none of the 26 patients in the Nissen-Rossetti group had abnormal oesophageal acid exposure (P = 0.11; Fisher exact test).

The median percentage time with oesophageal pH less than 4 was significantly higher in the Dor group compared to the Nissen-Rossetti group (2; range 0.8-10 vs 0.35; range 0-2) (P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U-test) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Oesophago-gastric pH monitoring at 24-mo follow-up. Median percentage of total time with oesophageal acid exposure in patients with partial and total fundoplication (P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U-test).

DISCUSSION

At present, the aetiology of primary achalasia is still not clear, and only palliative and not curative treatments for this disease are available. The goal of the current therapeutic options is the long-term relief of dysphagia, preventing recurrences and improving QoL. The surgical management of achalasia seems to achieve, among the various treatment options, the best short and long-term clinical outcome, especially a minimally invasive approach, currently considered the treatment of choice for patients with idiopathic achalasia[6-9,18-23].

However, although laparoscopic Heller myotomy has become an established therapeutic method and has achieved rapid and widespread diffusion, some points regarding the surgical procedure are still controversial.

The length of myotomy is the first matter of debate.

Although some authors have proposed a limited myotomy on the lower oesophagus, preserving a small portion of the LES to prevent postoperative reflux[24,25], most authors have recommended a myotomy extending 4-6 cm on the oesophagus and 1-2 cm on the gastric side followed by an anti-reflux procedure[4,5,10,18].

In this study, we performed an oesophago-gastric myotomy 5-6 cm long, with a proximal extension of 2-2.5 cm above the Z-line and a distal extension of 3-3.5 cm below the same landmark.

In a previous experimental study with intraoperative computerized manometry, we observed that myotomy of the oesophageal portion of the LES (without dissection of the gastric fibres) did not lead to a significant variation in the sphincteric pressure or vector volume. Instead, dissection of the gastric fibres for at least 2-2.5 cm on the anterior gastric wall, created a significant modification of the LES pressure profile[26]. This may be due to destruction of the anterior portion of the semicircular clasps and of the gastric sling fibres, which once disconnected from the posterior branches, lose their hook properties decompressing the posterior fibres[27].

These findings led us not to perform a long oesophageal myotomy, reducing damage to the oesophageal musculature and extending the myotomy for 3-3.5 cm on the gastric side. This point seems particularly relevant if we consider that some studies reported, by means of 24-h ambulatory oesophageal manometry, signals of reappearance of peristaltic activity after Heller’s myotomy[28-31]. On the other hand, in 8 patients in the present study at manometric follow-up, complete peristaltic contractions of the oesophageal body were found. The association of an anti-reflux procedure with myotomy is still a controversial issue.

Ellis, based on a case series, performed a thoracoscopic limited oesophago-myotomy without a fundoplication, obtaining good results for relief of dysphagia with a low incidence of postoperative GER[24,25]. However, according to the literature, the thoracoscopic approach carries both technical disadvantages and poorer postoperative outcome, compared to laparoscopic access[32-35].

Other authors, based on retrospective studies, reported excellent outcomes by adding an anti-reflux procedure (Dor or Toupet) to either laparoscopic or laparotomic myotomy, showing a 5.7% to 10% incidence of pathological GER at short- and long-term follow-up[36-39].

On the other hand, some authors proposed a limited mobilization of the lower oesophagus and preservation of the oesophageal lateral and posterior attachments, with the intention of preserving the native anti-reflux mechanism, avoiding an anti-reflux procedure after the myotomy[40].

The first and the only prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial comparing Heller myotomy vs Heller myotomy with an anti-reflux procedure was designed by Richards, an historic supporter of laparoscopic Heller myotomy without fundoplication[41]. The same author reported a 47.6% incidence of pathological acid reflux in the group with Heller myotomy alone, vs 9.1% in the group with associated anterior fundoplication (P = 0.005), whereas no significant differences in surgical outcome and postoperative dysphagia were found. The author concluded that the addition of a Dor fundoplication to Heller myotomy provided more reliable protection from postoperative pathological GER.

Furthermore, recent retrospective studies evaluating the long-term follow-up of laparoscopic and trans-thoracic Heller myotomy, despite effective relief of dysphagia, showed an incidence of pathological GER between 11.3% and 80%[42-44].

Moreover, the results of a recent meta-analysis suggest that adding a fundoplication decreases pathologic acid exposure and GER symptoms after myotomy, and that the resolution of dysphagia is independent of whether a fundoplication is performed[11].

There is no agreement on the type of fundoplication to carry out.

The proponents of partial fundoplication, such as anterior 180° and 270° posterior, argue that the addition of a total fundoplication on the myotomized oesophagus may impair the oesophageal clearance, retarding oesophageal emptying and resulting in a higher rate of recurrent dysphagia[41]. However, few available data support this point of view.

Topart et al[45]showed a recurrence and re-operation rate of 82.4% associated with progressive oesophageal dilation in a series of 17 patients undergoing complete myotomy and short floppy Nissen fundoplication.

Wills demonstrated a similar incidence of postoperative dysphagia, regurgitation and heartburn between patients with partial and total fundoplication after Heller myotomy[46].

Falkenback, based on a prospective randomized trial comparing Heller myotomy alone with Heller plus Nissen fundoplication, found no significant difference at long-term follow-up in the rate of postoperative dysphagia, in contrast to the incidence of postoperative pathological GER, which was significantly higher in the group with Heller myotomy alone (13% vs 0.15%)[47].

Recently, Rossetti et al[10] reported the long-term follow-up of 195 consecutive laparoscopic procedures for the treatment of oesophageal achalasia with Heller myotomy plus Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication. This approach achieved good results with a 2.2% incidence of postoperative dysphagia and an absence of pathological GER in all 75 patients undergoing instrumental follow-up.

The first prospective randomized trial, comparing total Nissen fundoplication with a 180° anterior Dor fundoplication after myotomy for grade I and II achalasia, has recently been published[48]. The authors reported a 15% incidence of dysphagia in the group with Heller myotomy plus total fundoplication vs 2.8% in the group with anterior fundoplication (P < 0.001), whereas no significant difference in GER control was found, even when the incidence of pathological GER was higher in the Dor group compared to the Nissen group (5.6% vs 0%). Furthermore, the authors found a correlation between the grade of oesophageal dilation and recurrence of dysphagia, concluding that the Nissen fundoplication could be considered in selected cases such as younger patients with grade I achalasia.

The present study aimed to compare the surgical and mid-term outcome of total fundoplication with anterior partial fundoplication following myotomy in the treatment of primary achalasia. Unlike the previous study[48], based on the results of barium oesophagogram, patients with stage 3 achalasia were not excluded. Moreover, the similar characteristics between the 2 groups of patients and the strict exclusion criteria allowed a reliable comparison between the two groups.

Our data show firstly, a good and similar immediate postoperative outcome for both Nissen-Rossetti and Dor fundoplication.

Indeed, the two major intraoperative complications did not lead to a poorer postoperative outcome, and no significant difference in hospitalization between the two patient groups was observed. On the other hand, only one of these complications, pneumothorax, was probably related to the type of fundoplication, which occurred during mobilization of the lower mediastinal oesophagus, which in this case, appeared to be strongly adherent to the pleura. Furthermore, at 24 mo follow-up, there was no significant difference in the symptom score and QoL between the patients with partial and total fundoplication. Only 4 patients with grade 3 achalasia had occasional and moderate postoperative dysphagia and were equally distributed in the 2 groups.

In our opinion, these data, in contrast to a previous study[48], reflect both our surgical technique and evaluation of the clinical results using a score which combined the severity and frequency of symptoms. The use of the anterior wall of the stomach in fashioning the wrap allows the construction of a neo-sphincter that adequately relaxes during swallowing, thus allowing normal bolus transit through the gastroesophageal junction even in patients with impaired oesophageal motility[49,50].

Moreover, endoscopic and manometric calibration of the wrap leads to an objective evaluation of the fundoplication, avoiding a too tight or too long wrap that may increase the incidence of postoperative dysphagia[10].

Concerning the evaluation of symptoms, dysphagia is a symptom which may indicate a sensation of impaired, difficult or obstructed bolus transit through the oesophagus and may occur with variable frequency. In patients with achalasia treated surgically, although dysphagia may dramatically improve, the impaired oesophageal motility persists despite treatment.

Occasionally, after surgery, some patients may have rapid and excessive food intake which, in the presence of inadequate oesophageal clearance, may increase the risk of postoperative dysphagia. Furthermore, episodic emotional stress and psychological abnormalities may influence the subjective perception of bolus transit.

For these reasons, only a score which combines severity with frequency of symptoms may lead to an adequate evaluation of postoperative dysphagia.

This study, in contrast to other reports[41,51], seems to indicate that total fundoplication on a myotomized oesophagus, does not impair oesophageal bolus transit more than an anterior partial fundoplication.

Similarly, our data, according to Rossetti et al[10], also suggest that at mid-term follow-up, the calibrated Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication, performed according to our technique, does not represent an obstacle to oesophageal emptying after Heller myotomy. Obviously, further research to confirm these results at long-term follow-up with larger sample sizes are needed.

At 24 mo follow-up, although the difference in the incidence of pathological reflux was not statistically significant (the power of the study was low for the limited number of patients), none of the patients with Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication showed pathological oesophageal acid exposure, in contrast to four patients with abnormal oesophageal pH-monitoring results in the Dor group. Furthermore, the median percentage time with oesophageal pH less than 4 was significantly higher in the Dor group compared to the Nissen-Rossetti group.

Similarly, the mean resting pressure of the neo-sphincter was significantly higher in patients with total fundoplication than in those with partial fundoplication.

These findings seem to indicate that total fundoplication allows more reliable protection from acid GER, compared to anterior partial fundoplication. On the other hand, the literature suggests that Nissen fundoplication is effective in reversing not only acid but also non-acid reflux[52].

Interestingly, at 2 years follow-up, we found an incidence of pathological reflux of 13.3% in patients with partial fundoplication which was higher than that reported at 6-mo follow-up in a previous prospective randomized study[41].

Moreover, other recent retrospective analyses suggest a progressive increase in oesophageal acid exposure at long-term follow-up in achalasic patients treated with myotomy plus Dor fundoplication[6,53].

These data raise the question of whether partial anterior fundoplication is able to prevent pathological oesophageal exposure over time.

However, this is beyond the scope of this study and long-term follow-up results are needed to verify the effect of pathological reflux on the clinical outcome of patients undergoing surgery for oesophageal achalasia. The higher incidence of reflux symptoms and pathological reflux in the Dor group did not lead to worsening of the symptom score and QoL. This probably reflects the fact that, after surgical treatment, the patients with abnormal oesophageal acid exposure reported only mild heartburn and regurgitation and were euphoric about their ability to eat.

According to Ponce, patient satisfaction was more related to improvement in dysphagia, than to the absence of reflux symptoms[54]. However, other authors have emphasized the harm of GER in patients with impaired oesophageal clearance and myotomized oesophagus[10]. In our study, 24 mo after surgery, patients with pathological oesophageal acid reflux showed, at most, grade A oesophagitis and underwent standard dose PPI therapy.

In conclusion, our study seems to indicate that total and anterior partial fundoplication, performed after Heller myotomy for oesophageal achalasia, showed similar mid-term results in term of dysphagia and QoL. Furthermore, Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication seems superior to Dor fundoplication in preventing postoperative oesophageal acid exposure, even if the clinical and statistical relevance of this finding was not clearly evident at the mid-term follow-up.

COMMENTS

Background

Oesophageal achalasia is the best characterised oesophageal motility disorder and is caused by irreversible degeneration of oesophageal myenteric plexus neurons. It is characterised by aperistalsis or uncoordinated contractions of the oesophageal body and incomplete or absent post-deglutitive relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter.

Research frontiers

Although the surgical therapeutic option is considered the gold standard, many issues regarding the surgical technique are still debated such as the length of myotomy, the association of an anti-reflux procedure with myotomy and the type of fundoplication to perform.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Although the total 360° wrap is generally considered an obstacle to normal oesophago-gastric transit in the presence of defective peristaltic activity, some authors have shown that Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication is not an obstacle to oesophageal emptying after Heller myotomy, achieving excellent results in terms of dysphagia and providing total protection from gastroesophageal reflux. Moreover, the only prospective randomized trial comparing total Nissen fundoplication with the 180° anterior Dor fundoplication after myotomy, was carried out for grade I and II achalasia only, evaluating dysphagia recurrences using a non specific/dedicated score.

Applications

The study seems to indicate that total and anterior partial fundoplication, performed after Heller myotomy for oesophageal achalasia, shows similar mid-term results in term of dysphagia and quality of life. Furthermore, Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication seems superior to Dor fundoplication in preventing postoperative oesophageal acid exposure, even if the clinical and statistical relevance of this finding was not clearly evident at the mid-term follow-up. In other words, not only partial fundoplication, but also the total wrap may be considered when choosing the best anti-reflux procedure after Heller myotomy for oesophageal achalasia. Obviously, our data should be confirmed by further randomized controlled trials with larger series and longer follow-up.

Terminology

Nissen, Dor and Toupet fundoplications represent anti-reflux procedures which can be performed after myotomy in the treatment of oesophageal achalasia. The first, is a total (360°) wrap, whereas, the remaining techniques are partial wraps (180° anterior and 180° posterior, respectively).

Peer review

This is an excellent, provocative study that needs to be confirmed with a randomized trial.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Eric S Hungness, MD, FACS, Assistant Professor, Division of Gastrointestinal and Oncologic Surgery, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 676 N. St. Clair St., Suite 650, Chicago, IL 60611-2908, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut. 2001;49:145–151. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vantrappen G, Hellemans J. Treatment of achalasia and related motor disorders. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decker G, Borie F, Bouamrirene D, Veyrac M, Guillon F, Fingerhut A, Millat B. Gastrointestinal quality of life before and after laparoscopic heller myotomy with partial posterior fundoplication. Ann Surg. 2002;236:750–758; discussion 758. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200212000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patti MG, Pellegrini CA, Horgan S, Arcerito M, Omelanczuk P, Tamburini A, Diener U, Eubanks TR, Way LW. Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia: an 8-year experience with 168 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;230:587–593; discussion 593-594. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patti MG, Diener U, Molena D. Esophageal achalasia: preoperative assessment and postoperative follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:11–12. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Henríquez A, Cortés C. Late results of a prospective randomised study comparing forceful dilatation and oesophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia. Gut. 1989;30:299–304. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West RL, Hirsch DP, Bartelsman JF, de Borst J, Ferwerda G, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Long term results of pneumatic dilation in achalasia followed for more than 5 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1346–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neubrand M, Scheurlen C, Schepke M, Sauerbruch T. Long-term results and prognostic factors in the treatment of achalasia with botulinum toxin. Endoscopy. 2002;34:519–523. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21–35. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossetti G, Brusciano L, Amato G, Maffettone V, Napolitano V, Russo G, Izzo D, Russo F, Pizza F, Del Genio G, et al. A total fundoplication is not an obstacle to esophageal emptying after heller myotomy for achalasia: results of a long-term follow up. Ann Surg. 2005;241:614–621. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157271.69192.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos GM, Vittinghoff E, Rabl C, Takata M, Gadenstätter M, Lin F, Ciovica R. Endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2009;249:45–57. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e43ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Portale G, Battaglia G, Molena D, Carta A, Costantino M, Nicoletti L, Ancona E. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of failures after laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. Ann Surg. 2002;235:186–192. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200202000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta S, Bennett J, Mahon D, Rhodes M. Prospective trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitor therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Seven-year follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1312–1316; discussion 1316-1317. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel AA, Donegan D, Albert T. The 36-item short form. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:126–134. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passaretti S, Zaninotto G, Di Martino N, Leo P, Costantini M, Baldi F. Standards for oesophageal manometry. A position statement from the Gruppo Italiano di Studio Motilità Apparato Digerente (GISMAD) Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:46–55. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson LF, Demeester TR. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1974;62:325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costantini M, Zaninotto G, Guirroli E, Rizzetto C, Portale G, Ruol A, Nicoletti L, Ancona E. The laparoscopic Heller-Dor operation remains an effective treatment for esophageal achalasia at a minimum 6-year follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramacciato G, Mercantini P, Amodio PM, Stipa F, Corigliano N, Ziparo V. Minimally invasive surgical treatment of esophageal achalasia. JSLS. 2003;7:219–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrokhi F, Vaezi MF. Idiopathic (primary) achalasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:38. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anselmino M, Perdikis G, Hinder RA, Polishuk PV, Wilson P, Terry JD, Lanspa SJ. Heller myotomy is superior to dilatation for the treatment of early achalasia. Arch Surg. 1997;132:233–240. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430270019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kostic S, Johnsson E, Kjellin A, Ruth M, Lönroth H, Andersson M, Lundell L. Health economic evaluation of therapeutic strategies in patients with idiopathic achalasia: results of a randomized trial comparing pneumatic dilatation with laparoscopic cardiomyotomy. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1184–1189. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karamanolis G, Sgouros S, Karatzias G, Papadopoulou E, Vasiliadis K, Stefanidis G, Mantides A. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:270–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis FH, Gibb SP, Crozier RE. Esophagomyotomy for achalasia of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 1980;192:157–161. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198008000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis FH. Oesophagomyotomy for achalasia: a 22-year experience. Br J Surg. 1993;80:882–885. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Martino N, Monaco L, Izzo G, Cosenza A, Torelli F, Basciotti A, Brillantino A. The effect of esophageal myotomy and myectomy on the lower esophageal sphincter pressure profile: intraoperative computerized manometry study. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:160–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2005.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein HJ, Korn O, Liebermann-Meffert D. Manometric vector volume analysis to assess lower esophageal sphincter function. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1995;84:151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Martino N, Bortolotti M, Izzo G, Maffettone V, Monaco L, Del Genio A. 24-hour esophageal ambulatory manometry in patients with achalasia of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 1997;10:121–127. doi: 10.1093/dote/10.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Genio A, Di Martino N, Izzo G, Landolfi V, Nuzzo A, Zampiello P. [Surgical therapy of esophageal achalasia] Ann Ital Chir. 1990;61:239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ponce J, Miralbés M, Garrigues V, Berenguer J. Return of esophageal peristalsis after Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:545–547. doi: 10.1007/BF01320323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Martino N, Izzo G, Monaco L, Sodano B, Torelli F, Del Genio A. [Surgical treatment of esophageal achalasia by Heller+Nissen laparoscopic procedure. A 24-hour ambulatory esophageal manometry study] Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2003;49:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urbach DR, Hansen PD, Khajanchee YS, Swanstrom LL. A decision analysis of the optimal initial approach to achalasia: laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication, thoracoscopic Heller myotomy, pneumatic dilatation, or botulinum toxin injection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:192–205. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patti MG, Arcerito M, De Pinto M, Feo CV, Tong J, Gantert W, Way LW. Comparison of thoracoscopic and laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:561–566. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter JG, Richardson WS. Surgical management of achalasia. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:993–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cade R. Heller’s myotomy: thoracoscopic or laparoscopic? Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:279–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonavina L, Nosadini A, Bardini R, Baessato M, Peracchia A. Primary treatment of esophageal achalasia. Long-term results of myotomy and Dor fundoplication. Arch Surg. 1992;127:222–226; discussion 227. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420020112016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ancona E, Peracchia A, Zaninotto G, Rossi M, Bonavina L, Segalin A. Heller laparoscopic cardiomyotomy with antireflux anterior fundoplication (Dor) in the treatment of esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:459–461. doi: 10.1007/BF00311744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patti MG, Molena D, Fisichella PM, Whang K, Yamada H, Perretta S, Way LW. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication for achalasia: analysis of successes and failures. Arch Surg. 2001;136:870–877. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.8.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anselmino M, Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Rossi M, Boccu C, Molena D, Ancona E. One-year follow-up after laparoscopic Heller-Dor operation for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s004649900283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parshad R, Hazrah P, Saraya A, Garg P, Makharia G. Symptomatic outcome of laparoscopic cardiomyotomy without an antireflux procedure: experience in initial 40 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:139–143. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318168db86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richards WO, Torquati A, Holzman MD, Khaitan L, Byrne D, Lutfi R, Sharp KW. Heller myotomy versus Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication for achalasia: a prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:405–412; discussion 412-415. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000136940.32255.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindenmann J, Maier A, Eherer A, Matzi V, Tomaselli F, Smolle J, Smolle-Juettner FM. The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux after transthoracic esophagocardio-myotomy without fundoplication: a long term follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta R, Sample C, Bamehriz F, Birch D, Anvari M. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic heller cardiomyotomy without an anti-reflux procedure. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:129–132. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000166987.82227.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robert M, Poncet G, Mion F, Boulez J. Results of laparoscopic Heller myotomy without anti-reflux procedure in achalasia. Monocentric prospective study of 106 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:866–874. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Topart P, Deschamps C, Taillefer R, Duranceau A. Long-term effect of total fundoplication on the myotomized esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:1046–1051; discussion 1051-1052. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90068-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wills VL, Hunt DR. Functional outcome after Heller myotomy and fundoplication for achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:408–413. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falkenback D, Johansson J, Oberg S, Kjellin A, Wenner J, Zilling T, Johnsson F, Von Holstein CS, Walther B. Heller’s esophagomyotomy with or without a 360 degrees floppy Nissen fundoplication for achalasia. Long-term results from a prospective randomized study. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2003.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rebecchi F, Giaccone C, Farinella E, Campaci R, Morino M. Randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus Dor fundoplication versus Nissen fundoplication for achalasia: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1023–1030. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190a776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patti MG, Robinson T, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Fisichella PM, Way LW. Total fundoplication is superior to partial fundoplication even when esophageal peristalsis is weak. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:863–869; discussion 869-870. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pizza F, Rossetti G, Del Genio G, Maffettone V, Brusciano L, Del Genio A. Influence of esophageal motility on the outcome of laparoscopic total fundoplication. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patti MG, Fisichella PM, Perretta S, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Robinson T, Way LW. Impact of minimally invasive surgery on the treatment of esophageal achalasia: a decade of change. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:698–703; discussion 703-705. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.del Genio G, Tolone S, Rossetti G, Brusciano L, Pizza F, del Genio F, Russo F, Di Martino M, Lucido F, Barra L, et al. Objective assessment of gastroesophageal reflux after extended Heller myotomy and total fundoplication for achalasia with the use of 24-hour combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (MII-pH) Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:664–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsiaoussis J, Pechlivanides G, Gouvas N, Athanasakis E, Zervakis N, Manitides A, Xynos E. Patterns of esophageal acid exposure after laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy and Dor’s fundoplication for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1493–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9681-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ponce M, Ortiz V, Juan M, Garrigues V, Castellanos C, Ponce J. Gastroesophageal reflux, quality of life, and satisfaction in patients with achalasia treated with open cardiomyotomy and partial fundoplication. Am J Surg. 2003;185:560–564. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]