Abstract

Context: Hospital cost shifting—charging private payers more in response to shortfalls in public payments—has long been part of the debate over health care policy. Despite the abundance of theoretical and empirical literature on the subject, it has not been critically reviewed and interpreted since Morrisey did so nearly fifteen years ago. Much has changed since then, in both empirical technique and the health care landscape. This article examines the theoretical and empirical literature on cost shifting since 1996, synthesizes the predominant findings, suggests their implications for the future of health care costs, and puts them in the current policy context.

Methods: The relevant literature was identified by database search. Papers describing policies were considered first, since policy shapes the health care market in which cost shifting may or may not occur. Theoretical works were examined second, as theory provides hypotheses and structure for empirical work. The empirical literature was analyzed last in the context of the policy environment and in light of theoretical implications for appropriate econometric specification.

Findings: Most of the analyses and commentary based on descriptive, industrywide hospital payment-to-cost margins by payer provide a false impression that cost shifting is a large and pervasive phenomenon. More careful theoretical and empirical examinations suggest that cost shifting can and has occurred, but usually at a relatively low rate. Margin changes also are strongly influenced by the evolution of hospital and health plan market structures and changes in underlying costs.

Conclusions: Policymakers should view with a degree of skepticism most hospital and insurance industry claims of inevitable, large-scale cost shifting. Although some cost shifting may result from changes in public payment policy, it is just one of many possible effects. Moreover, changes in the balance of market power between hospitals and health care plans also significantly affect private prices. Since they may increase hospitals’ market power, provisions of the new health reform law that may encourage greater provider integration and consolidation should be implemented with caution.

Keywords: Cost shifting, Medicare, hospital charges, health insurance, health policy

The definition, existence, and extent of hospital “cost shifting” are points of debate among participants and stakeholders in discussions of health care policy and reform. The academic literature defines the term precisely and characterizes the range of its effect. Even though that literature has grown considerably in recent years, not since the mid-1990s has it been systematically reviewed and summarized (Morrisey 1993, 1994, 1996; see also Coulam and Gaumer 1991). In this article, I update those older reviews, summarize the relevant features of and changes to health care policy, and place the results in today's policy context.

That hospitals charge different payers (health plans and government programs) different amounts for the same service even at the same time is a phenomenon well known to economists as price discrimination (Reinhardt 2006). That hospitals charge one payer more because it received less (relative to costs or trend) from another also is widely believed. This is a dynamic, causal process that I call cost shifting, following Morrisey (1993, 1994, 1996) and Ginsburg (2003), among others. Price discrimination and cost shifting are related but different notions. The first depends on differences in market power, the ability to profitably charge one payer more than another but with no causal connection between the two prices charged. The second has a direct connection between prices charged. In cost shifting, if one payer (Medicare, say) pays less relative to costs, another (a private insurer, say) will necessarily pay more. Whereas cost shifting implies price discrimination, price discrimination does not imply that cost shifting has occurred or, if it has, at what rate (i.e., how much one payer's price changed relative to that of another).

That hospitals shift their costs among payers is intuitively appealing. Public payments—from Medicare or Medicaid—go down (again, relative to cost or trend, qualifiers that I will omit from now on), and as a consequence, private payments go up, taking health insurance premiums along with them. Karen Ignagni, the president and CEO of America's Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), described cost shifting as follows: “If you clamp down on one side of a balloon, the other side just gets bigger” (Sasseen and Arnst 2009, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/09_41/b4150026723556.htm). According to Dobson, DaVanzo, and Sen, it is a simple hydraulic effect: “As some pay less, others must pay more” (2006, 23).

Is this intuition correct? Are costs immutable and simply shifted from one payer (that pays less) to another (that necessarily pays more)? If providers shift costs, by how much do they do so? When casually expressed or generously interpreted, the idea of cost shifting conjures up a dollar-for-dollar trade-off; that is, one dollar less paid by Medicare or Medicaid results in one dollar more charged to private payers. At least one recent health insurance industry–funded report (PWC 2009) assumed this level of cost shifting.

Some health care policy stakeholders have an interest in convincing policymakers that cost shifting is both inevitable and large. Continuing the cost-shifting assumption (and ignoring a countervailing assumption of profit maximization, to which I will return later), if public payments are relatively less generous, then hospitals will raise private prices more than they would otherwise. In turn, insurers’ premiums for policies and self-insured firms’ health care costs would rise more quickly, making the private purchase and sponsorship of health care coverage relatively more difficult for consumers and firms, respectively. Thus, convincing policymakers to be concerned about cost shifting also is in the interest of the privately insured, employers, and the insurance and hospital industries, all of whom benefit from (or, at least, are not harmed by) higher public payments. Individuals and firms would rather not spend more for care, which cost shifting implies; insurance companies do not want to charge higher premiums; and hospitals would prefer higher public payments for their services.

Of course, if costs could be shifted significantly, public payment policy would have little leverage on total health care costs. In that case, cost shifting would amount to price adjustments that would force private payers to subsidize most of the public programs’ payment shortfalls. Thus, the extent of cost shifting is important. Is it dollar-for-dollar, or is it less? If less, by how much? In other words, how much leverage does public payment policy have on total health care costs? How much does it influence private prices and premiums? For how much cross-subsidization does it account? The literature, as I will show, answers these questions.

The literature offers several broad conclusions that modify Morrisey's (1993, 1994, 1996) main finding that cost shifting was small to nonexistent. First, based on theoretical considerations alone, the conditions necessary for cost shifting are possible but circumscribed. Furthermore, if there is cost shifting, it cannot always and forever be large and persistent. Second, the empirical literature finds that to the extent it has occurred at all, cost shifting usually is at a low rate. Instead, the vast majority of public payers’ shortfalls are accommodated by cost cutting, not cost shifting. Third, private payment-to-cost ratios are influenced by many factors other than public payment rates. Thus, changes in the former cannot, and should not, always or fully be explained by changes in the latter. Fourth, the rate of cost shifting largely depends on the intensity of price competition in the private market for hospital services, that is, the relative market power of hospitals and health care plans. Indeed, one cannot assume that estimates of cost shifting from one era or one market will apply at another time or in another place. Fifth and finally, private and public prices and margins can influence each other. In other words, the direction of causality between private and public payment levels goes both ways: they are jointly determined.

Besides reviewing the literature in this article, I provide a framework informed by theory for empirical specifications of hospital cost-shifting analysis. In that framework I identify the control factors and estimation techniques required to obtain unbiased cost-shifting estimates. (Additional technical detail pertaining to this framework is found in Frakt 2010a.) I also examine each empirical study in light of this framework. Although no study (on any subject) is perfect, some are stronger than others. The stronger studies that I identify provide the most credible estimates of hospital cost shifting and indicate how the phenomenon varies with market structure. Ultimately, by considering the full body of work—imperfect as each individual effort may be—I have been able to draw some robust conclusions.

In addition to public payer shortfalls, providing care to the uninsured may lead to hospital cost shifting and affect private premiums, although the estimates vary. Families USA (2005) estimated that private insurance premiums were about 10 percent higher in 2005 due to the use of health services by the uninsured, whereas both Kessler (2007) and Hadley and colleagues (2008) found less than a 2 percent effect. The remainder of my article focuses on hospital cost shifting from Medicare and Medicaid to private payers and does not cover what may be caused by the uninsured.

Background

For decades, concerns about cost shifting have played a role in the consideration of hospital payment policy. According to Starr (1982, 388), in the 1970s, “commercial insurance companies worried that if the government tried to solve its fiscal problems simply by tightening up cost-based reimbursement, the hospitals might simply shift the costs to patients who pay charges.” A 1992 report by the Medicare Prospective Payment Assessment Commission (ProPAC) asserted that hospitals could recoup from private payers underpayments by Medicare (ProPAC 1992). If that were so, hospitals would not need to fear inadequate government payments. Yet somewhat paradoxically, around the same time, hospitals used the cost-shifting argument to call for higher public payment rates (AHA 1989). More recently, during the debate preceding passage of the new health reform law—the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)—two insurance and hospital industry–funded studies (Fox and Pickering 2008; PWC 2009) and one peer-reviewed publication (Dobson et al. 2009) reasserted that half to all public payment shortfalls were shifted to private payers.

The issue of cost shifting is certain to arise again in the near future. Even though cost shifting was debated during consideration of the PPACA, public payment policy is not settled, nor will it ever be. The new health reform law includes many provisions designed to reduce the rate of growth of public-sector health care spending. For instance, among the law's provisions, annual updates in payments for Medicare hospital services will be reduced; payments for them will be based partly on quality measures; and payments for preventable hospital readmissions and hospital-acquired infections will be lowered (Davis et al. 2010; Kaiser Family Foundation 2010). In aggregate and over the ten years between 2010 and 2019, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the savings from lower Medicare hospital payments would be $113 billion (CBO 2010a).

In addition, Medicaid eligibility will expand in 2014 to all individuals with incomes below 133 percent of the federal poverty level. The CBO has estimated that by 2019, Medicaid enrollment will grow by 16 million individuals (CBO 2010b). Because some of these new Medicaid beneficiaries would otherwise have been covered by private plans (a crowd-out effect; see Pizer, Frakt, and Iezzoni 2011), the lower Medicaid payments relative to private rates may increase incentives to shift costs. Conversely, to the extent that the expansion of Medicaid—as well as the equally large (CBO 2010b) expansion of private coverage encouraged by the PPACA's individual mandate and insurance market reforms—reduces the costs of uninsurance and uncompensated care, the law may also reduce hospitals’ need to shift costs. Nevertheless, if past experience is any guide, when some of the PPACA's provisions are implemented, they are likely to be challenged by the hospital and insurance industries using cost-shifting arguments.

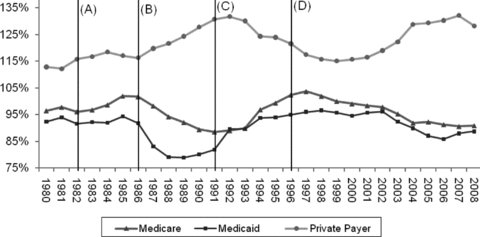

Much of the commentary in the literature pertaining to public and private payments to hospitals and their relationship refers to time series such as those depicted in Figure 1 (see, e.g., Dobson, DaVanzo, and Sen 2006; Lee al. 2003; Mayes 2004; Mayes and Hurley 2006; Zwanziger and Bamezei 2006). The figure shows the aggregate payment-to-cost ratios for all hospital-based services financed by private payers, Medicare, and Medicaid from 1980 through 2008. Except, perhaps, between 1980 and 1985, the private payment-to-cost ratio is negatively correlated with that of public programs. This is indicative of cost shifting, although other hypotheses are consistent with the evidence; that is, it may be coincidental or driven by other factors. As I suggest later, much of this may be explained by changes in hospital costs and changes in hospitals’ or plans’ price-setting power due to market size, reputation, and other factors relating to “market clout.”

Figure 1.

Aggregate Hospital Payment-to-Cost Ratios for Private Payers, Medicare, and Medicaid, 1980–2008.

Note: Medicaid includes Medicaid Disproportionate Share payments.

(A) = Beginning of Medicare Hospital Prospective Payment System (PPS) phase-in; (B) = PPS fully phased in; (C) = Era of commercial market managed care ascendance; (D) Balanced Budget Act (BBA) passage and managed care backlash.Source:AHA 2003, 2010.

Figure 1 breaks the years 1980 to 2008 into five spans of time by four lines, marked (A) through (D). These five eras correspond to periods over which the characteristics and structure of the health care market (including hospitals’ and plans’ market power) and policy landscape differed due to identifiable legislative or market events. In the following discussion, I focus on changes in Medicare policy and payments. Medicaid payments tend to track Medicare payments, as Figure 1 shows.

The Golden Stream (before 1983)

Policymakers have struggled with Medicare financing since the program's early years. The original design of hospital payments reimbursed hospitals retrospectively for all services at their reported costs plus 2 percent for for-profits and plus 1.5 percent for nonprofits (Weiner 1977). These so-called return on capital payments were eliminated in 1969 (U.S. Senate 1970), and the cost reimbursement system that replaced them included a so-called nursing differential that paid hospitals an additional 8.5 percent above inpatient nursing costs (Kinkead 1984). The 8.5 percent nursing differential was reduced to 5 percent in 1981 (SSA 1983) and was eliminated altogether by 1984 (Inzinga 1984). Thus, from the inception of the program into the 1980s, hospitals could earn greater Medicare revenue and profit simply by increasing their reported costs or a portion of them (inpatient nursing costs in the case of the nursing differential) (Mayes 2004).1 With no incentives for hospitals to contain costs, the system was described as “a license to spend, … a golden stream, more than doubling between 1970 and 1975, and doubling again by 1980” (Stevens 1989, 284).

Meanwhile, indemnity plans were the norm in the private sector. Without the leverage of network-based contracting (in which some providers could be excluded) and with payments rendered retrospectively on a fee-for-service basis, the private sector also had no success in controlling costs. In 1982, network-based managed care plans2 emerged when California passed a law allowing health insurance plans to selectively contract with hospitals. This statute was widely emulated elsewhere, thereby sowing the seeds for managed care's role in controlling costs in the 1990s (Bamezai et al. 1999).

Thus before 1983, attempts by public and private payers to control hospital costs were largely unsuccessful. In general, both rose over time, consistent with the positive correlation between the two that persisted until about 1985, which is evident in Figure 1. In the relationship between hospitals and their payers, hospitals had the lion's share of power. Price competition did not exist, and hospitals attracted physicians and patients with expensive, nonprice amenities and services (Bamezai et al. 1999).

Incentive Reversal (1983–1987)

With a goal of reducing domestic spending, the Reagan Administration targeted Medicare's hospital payments. Then Secretary of Health and Human Services Richard Schweiker became enamored of New Jersey's hospital prospective payment model, based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), and accordingly used it for Medicare's system (Mayes 2004). Under Medicare's prospective payment system (PPS), each hospital admission was assigned to one of almost five hundred DRGs, each of which was associated with a weight based on the average costs of treating patients in that DRG in prior years. The payment to a hospital for an admission was the product of the DRG weight and a conversion factor. Medicare could (and did) control the amount of payments to hospitals by adjusting the growth rate of the conversion factor and/or adjusting the relative DRG weights (Cutler 1998).

The critical element of the PPS was that prices were set in advance of admissions (i.e., prospectively), thereby putting hospitals—not Medicare—at financial risk for the cost of an admission. Rather than paying hospitals more if they did more, as the earlier system had done, the PPS encouraged them to do less and to pocket any surpluses of prices over costs. The reversal of incentives was designed to control costs, and the conversion factor and DRG weights were the policy levers for doing just that.

The PPS was phased in over four years. Hospitals quickly learned how to reduce lengths of stay and, thereby, costs. Since PPS payments were based on historical costs, the early years saw a spike in aggregate payment-to-cost ratios, as shown in Figure 1 (Coulam and Gaumer 1991).

Medicare, Congress's Cash Cow (1987–1992)

By 1987, the PPS was fully phased in, and Congress began using its policy levers to extract huge savings from Medicare and apply them to deficit reduction. The legislative mechanism was the annual budget reconciliation process. Robert Reischauer, director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) from 1989 to 1995, explained how the PPS was viewed and used by Congress:

Medicare was the cash cow! … Congress could get credited for deficit reduction without directly imposing a sacrifice on the public… . And to the extent that the reduction actually led to a true reduction in Medicare services, it would be difficult to trace back to the Medicare program or to political decision-makers. (Mayes 2004, 157–58)

Aggregate Medicare hospital payment-to-cost ratios fell every year from 1987 to 1992 because hospitals did not restrain costs as quickly as payments were adjusted (Guterman, Ashby, and Greene 1996). During this period, as Medicare margins fell, private pay margins grew. The effects of managed care had not yet been fully felt in the commercial market, leaving private purchasers vulnerable to hospitals’ market power. If there ever was a time when market conditions were ripe for cost shifting, this was it.

The Ascendance of Managed Care (1992–1997)

The role of market power in setting prices is clear when considering the experience of the 1990s. The business community, desperate to end the annual double-digit percentage increases in premiums, changed course by no longer offering traditional indemnity plans and instead encouraging the growth of managed care. Beginning in 1993, the majority of enrollees in private plans (51%) were covered by managed care, a number that grew rapidly thereafter; by 1995, 70 percent of enrollees were in managed care plans (Mayes 2004). As Robert Winters, head of the Business Roundtable's Health Care Task Force from 1988 to 1994, remembered, “What happened in the late 1980s and in the early 1990s, was that health care costs became such a significant part of corporate budgets that they attracted the very significant scrutiny of CEOs… . More and more CEOs [were] saying, ‘Goddammit, this has to stop!’” (Mayes 2004, 162–63).

What stopped it was network-based contracting. The willingness of plans and their employer sponsors to exclude certain hospitals from their networks strengthened plans’ negotiating position. That is, to be accepted into plans’ networks, hospitals had to negotiate with plans on price. In this way, the balance of hospitals’ and plans’ market power shifted, resulting in the downward private payment-to-cost ratio trend between 1992 and 1997 illustrated in Figure 1.

By contrast, public payers’ payment-to-cost ratios rose in the early 1990s. But this is not a (reverse) cost-shifting story because there is no evidence that public payments increased in response to decreasing private payments. Instead, the dynamics are better explained by changes in cost. Guterman, Ashby, and Greene (1996) found that the growth of hospital costs declined dramatically in the early 1990s, from above 8 percent in 1990 to below 2 percent by mid-decade, perhaps because of the pressures of managed care, a point echoed and empirically substantiated by Cutler (1998). The rise of hospital costs continued at low rates through the 1990s, averaging just 1.6 percent per year between 1994 and 1997. By contrast, Medicare payments per beneficiary to hospitals, which had been partially delinked from costs under the PPS, increased by 4.7 percent per year (Mayes and Hurley 2006). Thus, the movements in Figure 1's time series confound the effects of price and cost, which—along with obscuring market power effects—gives a false impression of large, pervasive cost shifting. Put simply, there are many ways for public and private payment-to-cost ratios to change, and the causal connection between prices (cost shifting) is just one of them.

The Managed Care Backlash and the BBA (1997–2008)

With so much room for costs to fall, managed care plans profited relatively easily for several years, negotiating with hospitals to accept lower increases in payments and reducing subscribers’ hospital use (Reinhardt 1999). But plans’ revenues fell throughout the 1990s as price competition squeezed inefficiencies and surplus from the system. In an attempt to maintain their profitability, plans imposed greater restrictions on enrollees, subjecting them to more stringent utilization reviews, tighter networks, elimination of coverage for certain services, and higher cost sharing (Mayes and Hurley 2006; Rice 1999).

These cost-saving measures became increasingly unpopular, and a managed care backlash ensued. In response, the states and the federal government enacted managed care reform and consumer protection laws (Sorian and Feder 1999). By 1997, the era of managed care's strong restraints on cost had ended and, with it, the low premium increases they had delivered earlier in the decade. America entered the current age of health care plans, with less restrictive network contracting embodied in the preferred provider organization (PPO), which became the norm. Although plans and hospitals still negotiate on price, because consumers dislike restrictions on their choice of providers, leverage shifted away from plans and toward hospitals. Reinforcing this shift, the number of hospital mergers rose in the late 1990s (Vogt 2009), and by the turn of the century, private payment-to-cost margins began to climb.

Coincidental with the popular rejection of managed care, Congress turned its attention to the budget deficit and again sought savings from Medicare. In 1997, it passed the Balanced Budget Act (BBA), which promised $115 billion in Medicare savings between 1998 and 2002 by eliminating retrospective cost-reimbursement for postacute care, long-term hospital services, and hospitals’ outpatient departments (Wu 2009). Thus, hospitals’ Medicare payment-to-cost ratios declined as those of private payers rose, but perhaps only coincidentally. The latter was facilitated by a shift in market power; the former by policy change. The extent to which they are causally related cannot be determined from Figure 1 alone.

In summary, Figure 1 reveals a negative correlation between public and private payment-to-cost ratios since 1985. Although this suggests cost shifting, it does not prove it. Other hypotheses are consistent with the evidence. Historical changes in hospital costs and the balance of hospitals’ and plans’ market power may explain all or some of the data. Only careful empirical analysis can reveal the causal effect of public prices on private prices, free of the confounding effects of changes in market power and hospital practices that impact costs.

Methods

To identify those studies providing empirical analyses of cost shifting or theoretical predictions of the phenomenon, I used Google Scholar to search the academic literature from 1996 to the present with the search string: health (payment OR rate) (Medicare OR Medicaid) “cost shift.” More than six hundred documents satisfied these search criteria, from which I selected only those that were not included in Morrisey's 1996 review, appeared in peer-reviewed journals, and either offered theoretical treatment of or attempted to estimate the size of a cost-shifting effect. The list was augmented by relevant papers published in 1996 or later cited by or citing those found in the Google Scholar search and meeting the aforementioned criteria. Although I did include papers pertaining exclusively to nursing homes’ and physicians’ cost shifting, they are not part of this review. They are, however, described in Frakt (2010a).

The final papers pertaining to hospitals’ cost shifting are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 cites those that provide theoretical developments, and Table 2 cites those with empirical findings. Those papers that include both are listed in both tables.

Table 1.

Theoretical Cost-Shift Literature (1996 to present)

| Citation | Assumptions | Predictions | Implications for Empirical Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies Assuming Profit Maximization by Providers | |||

| Rice et al. 1999; Showalter 1997 | Provider profit-maximizing behavior. | Cuts in public payments lead to lower quantity of care supplied to the public, a higher quantity supplied to private payers, and a lower private payer price. | Cost shifting is not expected if providers maximize profit. |

| Glazer and McGuire 2002 | Medicare sets prices independent of quality and must pay any willing qualified provider. Private payers negotiate quality-dependent prices and selectively contract. Provider quality is shared across payer types. | The presence of a private sector dilutes Medicare payment changes and can repair Medicare payment policy errors. Medicare can free-ride on private payers, receiving higher quality than that for which it pays. | A private payer's ability to exclude providers from its contract is a key source of bargaining power. Medicare's payment level may depend on factors (e.g., quality) correlated with private payer levels (i.e., may be endogenous). Public/private payer mix is a determinative factor in the extent that providers respond to Medicare payment changes. |

| Stensland, Gaumer, and Miller 2010 | Hospitals with strong financial resources have a high cost structure. | A high degree of hospital market power leads to high private prices and donations. These strong financial resources are associated with a high cost structure that is responsible for low Medicare margins. | Provider market power and costs are positively correlated with private payments. |

| Studies Assuming Utility Maximization by Providers | |||

| Clement 1997/1998; Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai 2000 | Hospitals maximize a utility function with profit and quantity components. | Cost shifting is possible if hospitals have underexploited their market power. | Measures of public and private payer volume (or one relative to the other) are related to cost-shifting behavior. |

| Cutler 1998 | Hospitals do not maximize profit. | Both cost shifting and cost cutting are expected responses due to public payment reductions. When insurers’ demand elasticity for hospital services is low, more cost shifting can occur. | Since cost cutting is a possible response to public payment reductions, cost-shifting analysis based on margins confounds price and cost effects. |

| Rosenman, Li, and Friesner 2000 | Hospitals maximize prestige (revenue subject to the constraint that it must cover costs). | Cost shifting may occur, depending on the provider's ability to cut costs. A higher number of publicly covered patients relative to privately covered ones increase the degree of cost shifting. | Public/private patient mix and grants are relevant to cost shifting. |

| Friesner and Rosenman 2002 | Hospitals maximize prestige (revenue subject to the constraint that it must cover costs). | Cost shifting and lower service intensity are substitute responses and should occur under similar circumstances. | Service intensity is related to cost shifting. |

Table 2.

Empirical Cost-Shift Literature (1996 to present)

| Citation | Principal Data Source | Unit of Observation and Methods | Dependent Variable(s) | Independent Variables | Cost Shifting Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gowrisankaran and Town 1997 | 1991 Current Population Survey (CPS), Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), and American Hospital Association (AHA) data. | Estimated a dynamic, structural model of the market for inpatient hospital services. Simulated welfare effects of 1984 change to Medicare hospital prospective payment system. | Model included the effects of entry, exit, investment, and multipayer pricing decisions. | Observable parameters include proportion of patients ill by payer, income threshold for free care, copayment, Medicare deductible, Medicare reimbursement rate, corporate tax rates, and discount rate. | Owing to more concentrated hospital markets, private payers experienced a 10% reduction in quality and a 1% decline in price. |

| Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||

| Stensland, Gaumer, and Miller 2010 | 2002–2006 Medicare hospital cost reports and 2005 IRS filings. | Hospital-year level descriptive analysis. | Medicare margins. | Non-Medicare margins. | Hospitals with lower non-Medicare margins had higher Medicare margins. In turn, hospitals with higher Medicare margins had lower costs. Hospitals with higher market power had higher costs, lower Medicare margins, and higher private pay margins. Illuminates factors relevant to price discrimination. |

| Dobson, DaVanzo, and Sen 2006 | 2000 American Hospital Association annual survey data. | State-level OLS. | Private payers’ payment-to-cost ratio. | Medicare, Medicaid, and uncompensated care payment-to-cost ratio and HMO penetration. | Found statistically significant evidence of price discrimination. HMO penetration and private payment-to-cost ratio negatively correlated. |

| Fixed-Effects Studies | |||||

| Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai 2000 | 1983–1991 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development hospital discharge data. | Hospital-year OLS including hospital fixed effects and instrumental variables for costs. | Per-patient private payment. | Per-patient revenue for Medicare and Medicaid, measures of hospital competition, ownership status, average cost (instrumented), case mix, and hospital fixed effects. | Private prices increased in response to reductions in Medicare rates (elasticities from 0.58 to 0.17, depending on hospital market concentration); they had a small and generally insignificant response to changes in Medicaid reimbursement. Inclusion of separate markups for Medicare and Medicaid across multiple years complicates interpretation of a dynamic cost-shift rate. |

| Zwanziger and Bamezai 2006 | 1993–2001 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development hospital discharge data. | Hospital-year level OLS with hospital fixed effects and instrumental variables for cost. | Per-patient private revenue. | Per-patient Medicare and Medicaid revenue, average costs, level of hospital market competition (HHI), and HHI-year interactions. | A 1% decrease in Medicare (Medicaid) prices caused a 0.17% (0.04%) private price increase. Between 1997 and 2001, 12.3% of the total increase in private prices was caused by public payment decreases. |

| Difference Model Studies | |||||

| Clement 1997/1998 | 1982–1983, 1985–1986, 1988–1989, 1991–1992 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development hospital discharge data. | Hospital-level OLS. | Change in logarithm of private revenue-cost margins. | Change in Medicare and Medicaid margins, total margin, other revenue, assets, hospital competition, HMO market strength, private occupancy rate, service mix, profit and ownership status, and other measures of case mix and hospital characteristics. | Negative correlations between public and private margins. Inclusion of separate margins for Medicare and Medicaid across multiple years complicates interpretation of a cost-shift rate. HMO market strength is negatively correlated with private prices. |

| Dranove and White 1998 | 1983, 1992 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development hospital discharge data. | Hospital-level OLS, SUR, and logit (for closings). | Changes in (1) private price/cost margin, (2) service levels, and (3) closings. | Public-payer caseload, hospital competition, hospital size, a high-tech hospital indicator, profit status, and drivers of demand. | Found no evidence of cost shifting. Service levels fell at Medicaid-dependent hospitals, and such hospitals were more likely to go out of business. Service level per admission positively correlated with hospital market concentration. |

| Friesner and Rosenman 2002 | 1995, 1998 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development hospital discharge data. | Hospital-level OLS. | Change in (1) private prices and (2) public and private-service intensity (length of stay). | Changes in Medicare or Medicaid charges and proportion unpaid, changes in number of beds, race, ethnicity, outpatient prices, and income. | Nonprofits cost shift, and for-profits do not. Both types lower service intensity for public payers. |

| Cutler 1998 | 1985–1995 data from Medicare cost reports and Interstudy. | Hospital-level OLS and logit (for closure and technology models). | (1) Changes in per-patient non-Medicare (includes Medicaid) private revenue, (2) hospital closure, (3) logarithm of number of hospital beds, (4) change in logarithm of FTE of nurses, and (5) indicators of acquisition of particular technologies. | Per-patient “Medicare bite”—growth difference between hospital market basket and Medicare payments—changes in cost, managed care enrollment, for-profit and ownership status, number of beds, and MSA size. | 1985–1990: at least a dollar-for-dollar cost shift, no evidence of an effect on hospital closure; 1990–1995: no evidence of cost shifting, a small effect indicating increased closures. In both periods, nursing input was reduced. Little evidence that payment changes affected hospital size or diffusion of technology. Rise in managed care explains differences over two time periods. |

| Wu 2009 | 1996, 2000 Medicare hospital cost reports. | Hospital-level OLS with hospital fixed effects and instrumental variables for Medicare price and HMO market penetration. | Change in non-Medicare price. | Change in Medicare price and revenue (instrumented), private/public payer mix, hospital ownership type, level and change in HMO market penetration (instrumented), change in case mix, hospital occupancy rate, level and change in Medicaid-to-Medicare physician fee ratio, share of for-profit hospitals, and hospital market concentration. | On average, about 20% of Medicare payment reductions are shifted to private payers. Degree of cost shifting is lower for hospitals in more competitive markets or markets with a higher share of for-profit hospitals. |

Note: Excludes any literature reviewed in Morrisey 1996.

Cost-Shifting Theory

My purpose in reviewing cost-shifting theory is to identify nonprice factors that may be relevant to the phenomenon. Such factors should be considered in empirical studies if they are to provide an unbiased estimate of cost shifting. I also describe the role of hospitals’ and plans’ market power and the implications of assuming that hospitals engage in profit-maximizing behavior regarding costs and prices. Finally, I consider what can happen when hospitals maximize something other than profit (generically termed utility maximization).

Market Power and Profit Maximization

One formalization of cost-shifting theory is concerned with a health care provider that treats both “public” and “private” patients. Public payers set provider payments by fiat and accept any willing provider. Traditional Medicare is the prototypical public payer, although state Medicaid programs have similar characteristics. In contrast, private payers negotiate payments with providers using their ability to selectively contract (through contracting networks) with a subset of them, which provides a source of negotiating power. Managed care companies are the prototypical private payers (Glazer and McGuire 2002).

This distinction highlights the role of “excludability” in hospital price setting. That is, hospitals in markets in which other hospitals offer the same services are subject to exclusion from private payers’ contracting networks. This is one source of leverage for health plans and drives private prices downward. In contrast, those hospitals that plans hesitate to exclude from their networks because of prestige or another distinctive characteristic may be able to extract high prices from plans. Similarly, a hospital with a local monopoly (perhaps because of a great distance to the closest competitor) cannot be excluded from plans’ networks, thus driving that hospital's prices upward. Hospitals operating near full capacity also can demand higher prices (Ho 2009).

The market power of firms that offer insurance and/or administer self-insured employer plans also affects private prices. For example, a firm with a large share of the market also has considerable power in negotiating the price of health care services. Even a relatively large hospital cannot afford to be excluded from a dominant plan's network, a phenomenon that pushes down the prices paid to hospitals. In such cases, if there is some competition among hospitals, there is little to no room to raise prices charged to a dominant plan. The reason is that such a plan would walk away from a hospital trying to do so and contract with a competing hospital instead (Morrisey 1996). The ability to price discriminate (charge one payer more than another) depends on a hospital's market power relative to that of each of its payers.

Hospital prices are thus set through a bargaining process between hospitals and plans (Ho 2009; Moriya, Vogt, and Gaynor 2010). Although the market power of these two entities is relevant to the price-setting process, the precise relationships between plans’ and hospitals’ market power, on the one hand, and price discrimination by hospitals across payers and its consequence for commercial premiums, on the other, are complex and not fully understood. The health economics community does generally agree, though, on the key principles and qualitative relationships among relevant factors (Frakt 2010b).

One such principle, explained earlier, is that the ability to price discriminate is necessary but not sufficient for cost shifting. Since price discrimination is driven by market power, a necessary but not sufficient condition for hospitals to shift costs from public to private payers is that hospitals have market power relative to plans. Market power cannot be profitably wielded indefinitely, however. Once a hospital has fully exploited its market power, it has exhausted its ability to extract additional revenue from further price increases. That is, an even higher price would drive away enough customers (plans) that revenue would decrease, not increase.

Cost shifting thus requires a change in the degree to which hospitals exercise their market power. To shift costs, a hospital must have untapped market power. That is, it must have an ability to price discriminate to an extent not fully exercised. If it then exploits more of its market power in response to a shortfall in payments from public programs, it will have shifted its costs. But once it has exploited all its market power, a hospital cannot shift costs further because it cannot price discriminate further. This is why an assumption of hospital profit maximization leaves no room for them to shift costs. If profits are at a maximum, they can only drop if prices go up and patients begin going elsewhere in response (Morrisey 1996).

Most economists reject the possibility of cost shifting by appealing to a profit maximization assumption (Morrisey and Cawley 2008). Using a multipayer model of prices and quantities (number of patients served or units of health care sold), Showalter (1997) showed the consequences of such an assumption. When public payers cut the price per patient to a hospital, that hospital recomputes what it charges each payer, in order to maximize its profit. The new set of prices is one for which quantity supplied to the public payer is lower, a simple result of supply and demand: a shift downward in price offered translates into lower number of patients served. A greater capacity is then available to serve more private patients. To fill that capacity (i.e., attract more patients from health plans), the hospital must lower its per-patient private price, again a simple consequence of supply and demand. Thus, in response to lower public payments, profit maximization predicts a volume shift (lower public volume leads to higher private volume) and a price spillover (lower private payments as well). This is the antithesis of the cost-shifting theory (McGuire and Pauly 1991; Rice et al. 1999). Morrisey (1993, 1994, 1996) pointed out that such a response also is expected for nonprofit hospitals that seek to maximize their revenue for charitable services.

So far I have considered the theoretical response of private prices and volumes to a change in public prices. Causality may run the other way, however: public prices respond to private prices. Glazer and McGuire (2002) imagined that all payers shared the same level of quality from each provider, which was assumed to be profit maximizing. Knowing this, public payers would benefit from the quality that private payers demand. By strategically underpaying, public programs would “free-ride” on private payers, getting more quality than they paid for. For example, high private prices fund the quality from which Medicare patients also benefit. In turn, Medicare pays rates that do not support the level of quality its beneficiaries receive. In this way, higher private rates can lead to lower Medicare rates, a cost shift but in the opposite direction normally assumed.

Another result of Glazer and McGuire's (2002) model is that the degree to which a profit-maximizing provider responds to changes in Medicare payments is a function of its public/private payer mix. A greater share of private payments dilutes whatever effect on quality the policy shift in public payments might have. The greater a hospital's share of public patients, the more leverage that the changes in public payment policy will have.

Wu (2009) terms Glazer and McGuire's “reverse causality” story (that public prices respond to private prices) a “strategy” hypothesis in the sense that public payers behave strategically in setting prices. In contrast, she labels the more standard story—that hospitals with unexploited market power can raise prices—as the “market power” hypothesis. These two hypotheses suggest a different consequence of payer mix. According to the market power hypothesis, hospitals with a larger share of private patients would cost shift more because of their greater bargaining power. Conversely, the strategy hypothesis proposes that hospitals with a larger share of private patients would cost shift less because they are less sensitive to (less reliant on) public payments.

Stensland, Gaumer, and Miller (2010) provided another mechanism by which public payer–based hospital margins respond to private payer–based revenue. They imagined a hospital with large market power that commands high markups over marginal costs. This permits a relaxed attitude toward cost, allowing them to rise. (Alternatively, the high cost structure itself could be a factor in large market power, perhaps due to high quality.) High costs cause Medicare margins to be negative.

In conclusion, the literature on cost-shifting theory based on profit maximization is clear. Cost shifting cannot exist if hospitals already maximize profit. However, if they do not fully exploit their market power, the theory suggests that the scope for cost shifting is still related to their degree of market power, as well as costs and quality, public/private payer mix, and plans’ market power. In addition, there are reasons to think that private payment levels influence public payments. Together, these theories suggest that causality could run both ways, that shifts in public payments could cause shifts in private payments and vice versa.

Though I have already touched on the implications for cost shifting if hospitals do not maximize profit, I next look at theories that attempt to explain what they may be maximizing instead.

Utility Maximization

Eighty-five percent of beds in community hospitals are in nonprofit or public institutions (Ginsburg 2003). There is no reason that nonprofit hospitals cannot charge profit-maximizing prices to some payers. For example, they may do so in order to maximize resources for charitable purposes. In such cases, there is no room for cost shifting (Morrisey 1993, 1994, 1996). Conversely, nonprofit hospitals can be guided by vague missions and influenced by stakeholders with different objectives. Consequently, they may not consistently maximize anything (Ginsburg 2003). Next I consider the case in which hospitals do not maximize profit but do maximize a combination of other well-defined factors (generically termed a utility function).

First, note that nonprofit and for-profit hospitals compete. In competition, the presence of for-profit hospitals may encourage nonprofits to become more efficient and cut costs. Likewise, the presence of nonprofits may induce for-profits to enhance their trustworthiness or quality (Kessler and McClellan 2001; Schlesinger et al. 2005). Competition, however, does not fully eliminate the differences between for-profits and nonprofits in their provision of uncompensated care, accessibility, quality, and trustworthiness (Schlesinger and Gray 2006).

Clement (1997/1998), citing earlier work on agency theory, argued that both nonprofit and for-profit hospitals maximize utility functions with both profit and quantity components. She therefore assumes a hospital strategy governed by a model developed by Dranove (1988) for which a hospital maximizes utility with both quantity and profit components over two payers. Such a model allows for cost shifting, provided that the hospital has underutilized its market power and sets prices commensurately lower than the market can profitably bear. Since volume is a component of the utility function, this result is intuitive: lower prices lead to higher volume so a hospital can maximize its utility without fully exploiting its market power and maximizing its profit. Like Clement (1997/1998), Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai (2000) also developed a theoretical model similar to Dranove's (1988), one assuming that hospitals maximize utility that depends on profits and volume. They also showed that cost shifting is possible. The theoretical work beginning with Dranove and further developed by Clement, Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai shows that measures of patient volume should be considered as independent variables in the specification of an empirical model of hospital prices.

Rosenman, Li, and Friesner (2000) hypothesized that nonprofit hospitals maximize their prestige by maximizing their revenue subject to the constraint that it must cover costs. The authors showed that doing so can lead to either cost shifting (higher private prices and lower private volume) or the opposite (lower private prices and higher private volume) in response to lower public payments. Which will result depends partly on the provider's ability to cut costs. The theory also predicts that payer mix is important. More public payer patients relative to private payer patients can increase the degree of cost shifting. Friesner and Rosenman (2002) offered a similar model of hospital prestige maximization stating that cost shifting and less intensive service provision are substitute responses and should result under similar circumstances.

Cutler (1998) provided an intuitive, graphical depiction of a theory of nonprofit hospital price setting under utility maximization, which shows that both cost shifting and cost cutting are expected when public payments to hospitals are reduced. The extent of each depends on the plans’ power to exclude hospitals from their networks. Cost shifting requires a private sector with a relatively low ability to do so (inelastic demand). As the ability to exclude hospitals increases (demand becomes more elastic), hospitals respond with more cost cutting than cost shifting. Hence, cost-shifting analysis based on margin (revenue divided by cost) can confound changes in price with changes in cost.

In summary, the literature on cost shifting assuming hospitals’ utility- (not merely profit-) maximizing behavior suggests that cost shifting is possible. The degree to which it occurs is expected to be related to public/private patient mix, changes in costs, and service intensity. One implication is that there are theoretical reasons to expect a hospital can cost shift if it does not maximize its profit or revenue from private payers.

Review of the Empirical Literature

The empirical literature identifies many possible hospital responses to decreases in public payments, including (1) a reduction in staff or wages, (2) a reduction in (underutilized) capacity, (3) changes in quality, (4) a reduction in services (trauma center, emergency rooms), (5) a lower diffusion rate of technology, (6) closure, (7) an upcoding of diagnostic information in order to get higher payments from Medicare, (8) volume shifting, and (9) cost shifting (Cutler 1998; Dafny 2005; Dranove and White 1998; Tai-Seale, Rice, and Stearns 1998). Given all these possible responses and in light of the relatively narrow range of circumstances in which cost shifting can theoretically occur, it is not surprising that the empirical literature shows that cost shifting usually does not completely offset shortfalls in public payments. With one exception, all the studies found no cost shifting or an amount far below dollar-for-dollar. The exception is Cutler (1998), who found dollar-for-dollar cost shifting between 1985 and 1990. But between 1990 and 1995, he found no evidence of cost shifting. The strongest study relevant to today's health care markets (Wu 2009) found an average 21 percent rate of cost shifting between 1996 and 2000.

Table 2's review of empirical literature is organized as follows. First, I examined studies that measure prices across hospitals but not over time. The results from these cross-sectional studies are often taken as evidence of cost shifting, but because they are a snapshot in time, they really are studies of price discrimination, a static phenomenon. Cost shifting is a dynamic relationship between prices, so they must be studied using data that include variations over time, not just across institutions. Next, I looked at two types of dynamic studies that exploit temporal as well as cross-sectional variation in prices. One type, fixed-effects specifications, measures price changes relative to an overall hospital-specific average. The other, difference models, measures price changes relative to a baseline year or a prior year. Both fixed-effects and difference models use hospitals as their own controls and are distinct and equally valid approaches (Wooldridge 2002).

One study (Gowrisankaran and Town 1997) estimates a model that is outside the typology of studies just explained. Using Current Population Survey data, hospital cost report data from the Health Care Financing Administration (now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services), and American Hospital Association data (all from 1991), the authors estimated a detailed (structural) model of the inpatient hospital market. The model captures the dynamics of a hospital industry in which for-profits and nonprofits compete and maximize different utility functions, have different preferences for investment, and face different levels of taxation. For-profits maximize profits, while nonprofits maximize a mix of profits and quality. The model includes the effects of hospital entry, exit, investment, and multipayers’ pricing decisions, as well as patients’ preferences for hospitals. Observable input parameters included proportion of patients requiring hospital services by payer, income threshold for free care, copayments, Medicare deductibles, Medicare reimbursement rates, corporate tax rates, and the discount rate.

The model is used to simulate the effects of Medicare's 1984 switch from a retrospective, cost-based system to a prospective payment system for hospital services. The authors found that the new payment system resulted in a 10 percent reduction in quality and a 1 percent decline in private price owing to the more concentrated hospital markets. The authors characterized this as a cost shift in that the price per unit of quality increased.

Cross-Sectional Studies

The most recent study of cost shifting is that by Stensland, Gaumer, and Miller (2010), in which they describe two hypotheses to explain the descriptive evidence that is frequently considered the signature of cost shifting. One hypothesis, promoted by the hospital and insurance industries or consulting firms on their behalf (Fox and Pickering 2008; PWC 2009; see also Dobson et al. 2009), is that costs are not influenced by Medicare payments (i.e., are exogenous) and that lower Medicare payment-to-cost margins induce hospitals to seek higher payments from private sources. The alternative dynamic, described earlier, is that hospitals with strong market power and a profitable payer mix have strong financial resources, high costs, and therefore low Medicare margins.

Although these are, strictly speaking, dynamic cost-shifting hypotheses, Stensland, Gaumer, and Miller test only static versions of them. That is, they examine only price discrimination. Pooling across years, the authors illustrate how margins correlate across payers and how they relate to costs and market power. Their descriptive findings are based on Medicare hospitals’ cost reports between 2002 and 2006. Because they stratify their analysis by degree of Medicare margin, it is (weakly) cross-sectional. This analysis is supplemented with two case studies of Chicago-area and Boston-area hospitals based on 2005 IRS filings and newspaper accounts to characterize qualitative differences in market power across hospitals. They discovered that hospitals with lower non-Medicare margins had higher Medicare margins. In turn, hospitals with higher Medicare margins had lower costs. Finally, hospitals with higher market power had higher costs, lower Medicare margins, and higher private pay margins. This descriptive analysis does not support causal inference, however. Thus, Stensland, Gaumer, and Miller did not find evidence of cost shifting. Indeed, they never tested for it (though, to be fair, neither did the industry-funded studies the authors tried to refute).

Dobson, DaVanzo, and Sen (2006) used a cross-sectional analysis of static public and private margins, which is more appropriate for the study of price discrimination than for cost shifting. Using American Hospital Association survey data, they used year 2000 state variations in payment-to-cost margins for private payers, relating them to variations in Medicare, Medicaid, and uncompensated care margins and controlling for HMO penetration rates. Although they found statistically significant evidence of price discrimination, their analysis did not control for costs. Since costs are in the denominator of the dependent and independent margin variables, the results confound price with cost effects, another reason why their findings do not provide evidence of cost shifting.

Fixed-Effects Specifications

Owing to the abundance of hospital payment and discharge data available from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD), many cost-shifting studies focused on the California market, spanning different methodologies and time periods. I review them in succession, beginning with Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai's study (2000), which considered the California market from 1983 through 1991. A year earlier, 1982, California enacted legislation that permitted establishment of selective contracting insurance products. By the end of the study period (1990), more than 80 percent of privately insured persons in California were enrolled in such plans. Thus, the period of study represents one of increasing price competition for hospitals due to the growing collective market share of network-based plans. In addition, during the 1980s Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements to California hospitals fell relative to costs (Dranove and White 1998).

Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai (2000) estimated a hospital-year level ordinary least squares (OLS) model of per-patient private payments with hospital and year fixed effects (meaning that the model controlled separately for each hospital's overall payment level, as well as yearly payment changes affecting all hospitals equally). Independent variables include per-patient Medicare and Medicaid revenue, measures of hospital competition, ownership status, average cost, and case mix. Costs and private payment levels are determined simultaneously because both are affected by quality (formally, costs are endogenous). To untangle the simultaneity and obtain unbiased estimates, costs were modeled with an instrumental variables (IV) technique.3 A large number of interactions were used to allow for the heterogeneity of public price variables by level of hospital competition, profit status, and time period (1983–1985, 1986–1988, 1989–1991). The study window was broken into three equal-size periods to test the hypothesis that cost shifting would be less feasible as managed care plans captured more of the market in later years.

The results indicate that hospitals—both for-profit and nonprofit—shifted costs in response to reductions in Medicare rates. The percentage increase in private payments in response to a 1 percent decrease in Medicare revenue varied across time period and hospital market concentration, from a low of 0.17 percent to a high of 0.59 percent. Nonprofit hospitals in less competitive markets tended to have lower rates of cost shifting than did those in more competitive markets. Responses to Medicaid cuts were an order of magnitude smaller and generally statistically insignificant. The results were consistent over time, despite the increasingly competitive market. This result is puzzling and not consistent with the findings of other studies, reviewed next. One possible explanation is that the instruments for cost (each hospital's cost relative to average hospital costs computed over the state and over the hospital's market) may be correlated with the dependent variable (private payments), which violates an assumption of the IV technique.

Zwanziger and Bamezei (2006) conducted a follow-up study in which they implemented a similar fixed-effects specification, focusing on the same dependent and key independent public payment variables from the same data source. The principal difference is that the study window, 1993 to 2001, was later than that considered in Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai's 2000 study. They also used a slightly different set of controls: average costs (instrumented), level of hospital competition (the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index [HHI]),4 and HHI-year interactions. The justification for returning to the cost-shifting question with a very similar model and the same data source but at a later time was twofold: (1) California hospitals’ price competition increased over the 1990s, and (2) the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 reduced the growth rate of Medicare hospital reimbursements. That the study window straddles the 1997 passage of the BBA is a particular strength, especially if one believes that its provisions for Medicare payment changes are a source of exogenous variation in Medicare prices.

Zwanziger and Bamezai's results (2006) were similar to those of their earlier study. They found no statistically significant difference in cost-shifting relationships between for-profit and nonprofit hospitals, no difference before and after the BBA, and no evidence of influence by the intensity of hospital competition. Their main finding is that a 1 percent decrease in Medicare (Medicaid) prices caused a 0.17 percent (0.04%) increase in private prices. Put another way, from 1997 to 2001, 12.3 percent of the total increase in private prices was caused by decreases in public payments.

Difference Models

Clement (1997/1998) examined the relationship between private revenue-cost margins and Medicare and Medicaid margins in California during three fiscal years (1985/1986, 1988/1989, 1991/1992) relative to a baseline year (1982/1983). Using OSHPD hospital discharge data, she estimated a hospital-level OLS with a dependent variable change in log of the private revenue-to-cost margin. Changes in Medicare's and Medicaid's payment-to-cost ratios (margins) were entered linearly and squared (not logarithmically) and interacted with year dummies. Control variables included the hospital's total margin, a measure of other revenue, a historical average of asset value, hospital competition, HMO market strength, private occupancy rate, service mix, profit and ownership status, and other measures of case mix and hospital characteristics. Clement found negative correlations between public and private margins, which could be evidence of cost shifting. However, because the model is of margins and not payment, one cannot separate the effects of payment and costs. In addition, the inclusion of separate margins for Medicare and Medicaid across multiple years complicates the calculation of a cost-shift rate.

Dranove and White (1998) also examined changes in private price-cost margins, as well as in service levels and hospital closings, in the California hospital market during the 1980s and early 1990s. Their approach was based on the notion that if hospitals can shift costs, they will do so at a greater rate if their public caseload is larger.5 Furthermore, hospitals with larger public caseloads may reduce quality to a greater extent than those with smaller public caseloads as public reimbursements decline. Dranove and White used service intensity (number of services per day, controlling for DRG) as a proxy for quality. With 1983 and 1992 California OSHPD hospital discharge data, they estimated hospital-level OLS, seemingly unrelated regression (SUR), and logit (for closings) models of the effect of Medicare and Medicaid caseloads (proportions of billed charges) on changes in private margins; service levels to Medicare, Medicaid, or private patients (three different equations); and hospital closings, controlling for hospital competition, hospital size, a high-tech hospital indicator,6 profit status, and drivers of demand. They tested different specifications with the independent variables entered as levels, changes, or both.

Dranove and White detected no evidence of cost shifting. Private margins decreased in hospitals with larger Medicare or Medicaid caseloads. But because margin, not price, was the dependent variable, one cannot say whether prices fell or costs rose. The intensity of services provided for all payer types was negatively associated with Medicare and Medicaid caseload sizes, although the results were not statistically significant for private payers. Dranove and White interpreted this negative intensity-caseload correlation across payers as support for the hypothesis that quality (as proxied by intensity) is a public good. Finally, they discovered evidence that Medicaid-dependent hospitals are more likely to go out of business. Taken together, the results indicate that the burden of public payer reductions is borne by public patients. Hospitals with higher public payer caseloads reduced quality and were more likely to close.

Friesner and Rosenman's study (2002) is the final one based on California OSHPD hospital discharge data (from 1995 and 1998). The authors distinguished between charges and payments. Charges are what is billed, and payments are what the hospital actually receives. Their models include measures of charges and the proportion of them not paid (i.e., 1-payments/charges). Using hospital-level OLS models, Friesner and Rosenman estimated the effects of changes in Medicare or Medicaid charges and the proportion unpaid on changes in private prices and public and private service intensity (length of stay), controlling for changes in number of beds, race, ethnicity, outpatient prices, and income. They estimated three models separately by profit status: one for private price changes, one for public service intensity changes, and one for private service intensity changes.

For the private price model, Friesner and Rosenman found a statistically significant and positive coefficient on the change in proportion of unpaid public charges for nonprofit hospitals but no statistically significant coefficient for for-profit hospitals. They interpreted this result as evidence that the former cost shifted and the latter did not. But they also found that the change in public charges was positively correlated with changes in private charges, which is not what hospitals actually receive in payments. For these reasons, their model did not support their conclusion of nonprofit hospitals’ cost shifting. That a decrease in the proportion of unpaid public charges was associated with an increase in private charges (not all of which were paid) is not evidence that lower public payments lead to higher private payments.

Cutler (1998) looked at the extent to which lower Medicare payments led to cost cutting (provision of fewer services and lower quality) versus cost shifting. His conclusions depended partly on the nature of the private market, which varied considerably over the two time periods he examined: 1985 to 1990 and 1990 to 1995. The time periods of study overlapped with a series of Medicare hospital payment reductions, including those established by the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985; the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Acts of 1987, 1989, 1990, and 1993; and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. For the key independent variable, Cutler constructed a measure of Medicare payment reduction he calls the “Medicare bite.” He noted that Medicare's hospital prospective payment system had been designed to increase with the costs of medical inputs. Reductions of the update factors, however, drove a wedge between the originally designed increases and the actual increases. The Medicare bite is the difference between the growth of the hospital market basket and the actual growth of Medicare payments multiplied by the number of Medicare patients served by the hospital.

Using data from Medicare cost reports and Interstudy, Cutler estimated by OLS the effect of the Medicare bite on hospital's changes in per-patient non-Medicare private revenue, hospital closures, number of hospital beds, changes in nurse staffing levels, and the diffusion of technology, controlling for changes in cost, managed care enrollment, profit and ownership status, number of beds, and metropolitan statistical area (MSA) size, but not, notably, hospital market structure. He found that between 1980 and 1985, hospitals shifted their costs dollar-for-dollar, a much greater cost shift rate than that found by Clement (1997/1998) and Zwanziger, Melnick, and Bamezai (2000), who studied the same time period (although those two studies were of California only). From 1990 to 1995, Cutler detected no evidence of cost shifting. Also, in the earlier period, there was no evidence that the lower Medicare payments affected hospital closures, but in the later period, there was a small effect indicating a greater number of closures. In both periods, nursing input was reduced as Medicare payments declined. There was little evidence that payment changes affected hospital size or diffusion of technology. Cutler's interpretation is clear. In the late 1980s, Medicare payment cuts were financed by shifting costs to the private sector. But with the rise of managed care in the early 1990s, cost shifting was no longer feasible, and cost cutting was the dominant response to lower Medicare payments.

Wu (2009) provided what may be the most careful study of the cost-shifting hypothesis relevant to today's health care markets. With a long difference model using 1996 and 2000 Medicare hospital cost report data, she examined the effect on private prices of reductions in Medicare payments to hospitals as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. She also looked at the heterogeneity of that effect across private-public payer mix (a test of the “market” versus “strategy” hypotheses), levels of hospital competition, and share of for-profit hospitals in the market. Of all studies reviewed, Wu's provides the strongest mitigation against and test of the potential endogeneity of Medicare payment (that both Medicare and private prices are driven by unobserved factors), thereby producing the most plausible estimate of its causal effect.

Wu constructed two instruments for changes in Medicare revenue: a “BBA bite” (similar to Cutler's “Medicare bite”) and a 1996 ratio of Medicare to non-Medicare discharges. The first of these, but not the second, is also used as an instrument for changes in Medicare price.7 The dependent variable was the change in the per-patient non-Medicare price, again similar to Cutler's. Two types of models were used, one with instrumented Medicare price changes as the key independent variable and the other with instrumented Medicare revenue changes as the key independent variable. Other independent variables included a bargaining-power measure (the share of private pay discharges less that for Medicare patients),8 hospital ownership type, level and change in HMO market penetration (also instrumented), change in case mix, hospital occupancy rate, level and change in Medicaid-to-Medicare physicians’ fee ratio, share of for-profit hospitals, and hospital market concentration.

Wu estimated a variety of OLS models with hospital fixed effects. In some models, the key independent Medicare price or revenue change variables were interacted with the bargaining-power variable (to test the market power versus the strategy hypothesis). In other models, the Medicare revenue change also was interacted with the hospital's characteristics (profit status, teaching hospital indicator, public hospital indicator, HMO market penetration level and change, and level and change in proportion of discharges in the market represented by for-profit hospitals). She discovered that on average, hospitals shifted twenty-one cents of each Medicare dollar lost to private payers. The degree of cost shifting varied by the hospitals’ bargaining power: a one standard deviation increase in such power increased the cost shifting rate to thirty-three cents on the dollar. There was no statistically significant evidence of heterogeneity in cost shifting by for-profit, teaching, or public hospital status. Nor did it vary by HMO market penetration or any change in it. There was less cost shifting in markets with a higher share of discharges from for-profit hospitals.

Discussion

From my analysis of all the cost-shifting literature since 1996, I am able to draw a number of important qualitative conclusions. First, if the time series of hospital margins by payer shown in Figure 1 is the signature of cost shifting, one would expect that careful studies of the phenomenon would find consistent, strong evidence of it. In fact, as a whole, the evidence does not support the notion that cost shifting is both large and pervasive. Instead, it reveals that cost shifting can occur but may not always do so. When it has occurred, it has generally been measured at a rate far below dollar-for-dollar (the sole exception being Cutler's 1998 measurement of dollar-for-dollar cost shifting between 1985 and 1990).

Taken together, these results strongly suggest that interpretations of the descriptive data in Figure 1 that go beyond an assumption of cost shifting are warranted. That is, cost shifting is just one of many possible responses to shortfalls in public payments to hospitals (another is cost cutting). Moreover, private payment-to-cost margins change for many reasons other than cost shifting (another is changes in the balance between hospitals’ and health plans’ market power). Indeed, the theoretical literature on the subject shows that cost shifting can take place only if hospitals both possess market power and have not fully exploited it. This limits both the conditions under which cost shifting is possible and its extent. Once market power is fully exploited, as it would be by a profit-maximizing firm, there is no more room for cost shifting. The theoretical literature also reveals the potential endogeneity of public prices in models of private ones, the role of costs and that of hospitals’ and plans’ market power.

Given these findings, what can be said about the likelihood of cost shifting in the future? Relative to the period in which cost shifting is most likely to have occurred at a relatively high rate (when indemnity plans were the norm, from 1987 to 1992), plans now are better able to resist price increases due to network-based contracting. Conversely, relative to the period in which there was likely no cost shifting (when tightly managed care dominated in the mid-1990s), price competition is now weaker because consumers are less accepting of networks with the same level of restrictions as existed then. To the extent that hospitals still have some unexploited market power, perhaps some cost shifting is possible, but given the results of papers I reviewed, it is likely to be at a rate closer to twenty cents on the dollar than the dollar-for-dollar rate suggested by industry-funded reports (PWC 2009) and by Cutler's (1998) estimate using data from 1985 to 1990, when the health care market was very different than the one that exists today.

The finding by Wu (2009), Cutler (1998), and others that hospitals’ and plans’ market power are relevant to cost shifting is not controversial. A large body of work relates plan market concentration (Dafny, Duggan, and Ramanarayanan 2009; Morrisey 2001; Robinson 2004; Wholey, Feldman, and Christianson 1995) and hospital market concentration (Bamezai et al. 1999; Berenson, Ginsburg, and Kemper 2010; Capps, Dranove, and Satterthwaite 2003; Robinson 2004; Robinson and Luft 1988; Vogt and Town 2006) to premiums and health care prices (Frakt 2010b). Therefore, cost shifting is not the only, and may not even be the most important, factor in the dynamics of private hospital prices.

The exploitation of market power is the privilege of private industry, subject to antitrust regulation, from which our market-based health system is not immune. Plans’ and hospitals’ market power may shift again with the new health reform law. The PPACA calls for pilot programs of the accountable care organization (ACO) payment model, which will compensate integrated groups of providers on a capitated basis for all the care for a population (Gold 2010). This will encourage providers to integrate, possibly increasing their market power (Frakt 2010b; Reinhardt 2010). If plans’ market power holds constant or is weakened, it is likely that private prices will increase, even without changes in public payments.

The PPACA also, however, includes provisions to expand public coverage via Medicaid and to reduce Medicare hospital payments relative to cost. Medicaid reimburses hospitals at rates far below those of private plans. Thus, if the crowd-out of private coverage encouraged by Medicaid expansion dominates the extent to which it eliminates what would otherwise be uncompensated care, it would create an incentive for cost shifting (Pizer, Frakt, and Iezzoni 2011). Furthermore, the law calls for reductions in annual updates in payments for hospital services, payments based on quality performance, and lower payments for preventable hospital readmissions and hospital-acquired infections, among others (Davis et al. 2010; Kaiser Family Foundation 2010).

If these changes cause public payments to fall further behind hospital costs as private payments go up at the same time, this will resemble cost shifting. However, judging from the literature on the subject just reviewed, it is unlikely that all or even most of the increase in private payments could be attributed to shortfalls in public ones. Cost shifting would be only part of the explanation; simultaneous changes in market power will likely explain the rest.