Abstract

Objectives

This study examined psychosocial characteristics of students who had used a cochlear implant (CI) since preschool and were evaluated when they were in elementary grades and again in high school. The study had four goals: (1) to determine the extent to which psychosocial skills documented in elementary grades were maintained into high school; (2) to assess the extent to which long-term CI users identified with the Deaf community or the hearing world or both; (3) to examine the association between group identification and the student’s sense of self-esteem, preferred communication mode, and spoken language skills; and (4) to describe the extracurricular world of the teenagers who were mainstreamed with hearing age-mates for most of their academic experience.

Design

As part of a larger study, 112 CI students (aged 15.0 to 18.6 yrs) or their parents completed questionnaires describing their social skills, and a subsample of 107 CI students completed group identification and self-esteem questionnaires. Results were compared with either a control group of hearing teenagers (N = 46) or age-appropriate hearing norms provided by the assessment developer.

Results

Average psychosocial ratings from both parents and students at both elementary grades and high school indicated a positive self-image throughout the school years. Seventy percent of the adolescents expressed either strong identification with the hearing community (32%) or mixed identification with both deaf and hearing communities (38%). Almost all CI students (95%) were mainstreamed for more than half of the day, and the majority of students (85%) were in the appropriate grade for their age. Virtually all CI students (98%) reported having hearing friends, and a majority reported having deaf friends. More than 75% of CI students reported that they used primarily spoken language to communicate and that good spoken language skills enabled them to participate more fully in all aspects of their lives. Identification with the hearing world was not associated with personal or social adjustment problems but was associated with better speech perception and English language skill. Ninety-four percent were active participants in high school activities and sports, and 50% held part-time jobs (a rate similar to that documented for hearing teens).

Conclusions

The majority of these early-implanted adolescents reported strong social skills, high self-esteem, and at least mixed identification with the hearing world. However, these results must be viewed in light of possible sources of sample selection bias and may not represent the psychosocial characteristics of the entire population of children receiving CIs.

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence poses challenges for all children, with its rapid physiological, psychological, and social development (Harter & Pike 1984). However, adolescence constitutes an even greater hurdle for those teenagers with severe-profound sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) who confront challenges of being deaf in a sound-dominated world—a world not always aware of their needs and challenges–especially in school settings (Leigh et al. 2009). The current investigation provides an opportunity to examine social skills and cultural identification of a large sample of adolescents who used a cochlear implant (CI) from a young age and were educated in a mainstream educational setting for most of their academic years. While other articles in this issue document their development of auditory, speech, language, and academic skills, we now turn to the social impact of long-term CI use on adaptation to the hearing world during high school.

Social Skills and Self-Esteem in Adolescents With SNHL

Difficulties with spoken communication imposed on individuals by severe-profound SNHL affect interactions with hearing peers and incidental learning of social behaviors in the hearing world. Appropriate social interactions typically are not directly taught but rather are learned by passive exposure to events witnessed or overheard in incidental situations (Calderon & Greenberg 2003). Deaf children who are raised by deaf parents may acquire social skills naturally in an environment where communication is dependent on visual and not on oral cues (Schirmer 2001). However, deaf children who are raised in hearing families may not acquire an understanding of the subtleties of social language. They may feel uncomfortable in social situations and/or may not be accepted by their hearing peers because they cannot pick up on important social-verbal behaviors (Marschark et al. 1993). Deficiencies in vocabulary and other aspects of English language affect the child’s ability to express his or her needs, thoughts, and feelings in the hearing world—and to understand the feelings expressed through spoken language.

Identification with Deaf Culture has been deemed one of the most important factors leading to positive self-esteem among deaf people (Schirmer 2001). By contrast, it has been reported that those with prelingual SNHL who attempt to fit into the hearing world are more likely to have poor self-esteem. A recent study measured factors associated with self-esteem among deaf students enrolled at California University at Northridge in a program specialized for deaf students (Jambor & Elliott 2005). They found that students with more profound deafness, those who used sign language at home and those who identified with a Deaf community, had higher self-esteem than those with less severe hearing loss who identified with the hearing world. However, some of the highest self-esteem ratings were observed in those who were able to get along well in both the Deaf and the hearing worlds, i.e., those who functioned well with both spoken and signed communication.

Use of CIs provides greater access to spoken language than was available previously to children with severe-profound hearing loss. Improved auditory access to speech may lead to improved social relationships with hearing peers (Bat-Chava & Deignan 2001; Bat-Chava et al. 2005). Adolescents with CIs tend to have hearing parents and therefore have greater social identification with the hearing than the Deaf community. Although CIs help deaf students to access the hearing world, they may not improve hearing sufficiently for these students to fit into the hearing world on an equal footing with hearing peers (Jambor & Elliott 2005). Although some studies warn of adverse consequences of early cochlear implantation on cultural identity (Kluwin & Stewart 2000), Wald and Knutson (2000) found that hearing identity of deaf individuals with CI is not associated with problems in either social adjustment or behavior.

Psychosocial Adjustment and Mainstreaming

Mainstreaming refers to educational placement of the child with special needs in regular classrooms with typically developing peers. Mainstreaming is favorably associated with academic and communication skill development in students with SNHL (Geers 1990), but some studies suggest that these advantages may be achieved at the cost of a negative self-image and social isolation. Students with hearing loss mainstreamed in the 1980s and early 1990s tended to be socially isolated, to feel lonely, to report lower self-esteem, and to be less well adjusted than those children in segregated settings (i.e., in nonmainstream environments) (Antia 1982; Charlson et al. 1992; Musselman et al. 1996). A preponderance of evidence from these studies supported segregated educational placements for fostering socioemotional growth, although there were a few studies with more positive findings for mainstream placements (Schwartz 1990). Parent support, good communication skills (i.e., intelligible speech or skilled interpreters), and participation in extracurricular activities were noted as key ingredients to successful social integration. However, in a sample of 100 mainstreamed adolescents from oral communication (OC) programs and supportive middle-class families, 26% reported that they often or sometimes felt alone in their school (Geers 1990).

Over the past 2 decades, educational settings and school experiences dramatically changed for children with severe-profound SNHL. Early cochlear implantation has become the accepted clinical practice for providing improved auditory access to spoken language. Twenty years ago, many children with severe-profound SNHL were enrolled in residential schools with other deaf children. Often these children remained in schools for the deaf or classrooms for the deaf through high school or at least through elementary grades. Today, most children who receive CIs at an early age are mainstreamed into classrooms with hearing age-mates in their neighborhood schools at younger ages than ever before. Many of these children are entering kindergarten or first grade at 5 or 6 yrs of age with language skills commensurate with hearing peers (Nicholas & Geers 2007; Geers et al. 2009). In general, parents observe greater self-esteem, confidence, and outgoing behavior in their children after implantation than before they received their CI (Bat-Chava & Deignan 2001; Bat-Chava et al. 2005; Leigh et al. 2009). However, parent report may lack veridicality for assessing psychosocial characteristics (Knutson & Stika 2009). Results obtained through a direct observation technique with a small sample of children with CIs indicated that their interaction with hearing peers tended to be unsuccessful (Boyd et al. 2000). Another study used direct observation to quantify the amount of success experienced in conversational interchanges between children with CIs and a hearing adult (Tye-Murray 2003). As a group, these children did not achieve conversational fluency on par with a matched group of hearing age-mates, experiencing significantly more communication breakdowns. Children who spent less time in communication breakdown were rated more favorably in terms of sociability, self-sufficiency, and cooperativeness than children with excessive communication breakdowns.

Previous studies of the psychosocial adjustment of deaf children focused on assessing children before adolescence, children without CIs, or children who received a CI during adolescence. The status of social skills and cultural identification in teenagers who have used a CI since preschool and have been enrolled primarily in a mainstream setting is not extensively documented and is the focus of the current investigation.

Assessment of Psychosocial Skills in Elementary Grades

Social skills of the participants in the current study were evaluated when they were 8 or 9 yrs old and in early elementary grades (CI-E) (Nicholas & Geers 2003). This group of individuals is particularly interesting because in preschool about half (52%) of the children were enrolled primarily in classrooms that used only OC and half (48%) were enrolled in classrooms that used sign to supplement spoken communication. None of the families reported enrolling their CI child in programs that used American Sign Language exclusively. At the time of the CI-E data collection, 83% of the children were either partially or fully mainstreamed with hearing age-mates in elementary grades (Geers & Brenner 2003). A self-report instrument was administered to directly assess each student’s perceived self-competence, and a rating scale was completed by a parent to assess perception of their child’s personal-social adjustment (Nicholas & Geers 2003). Their responses on the Picture Assessment of Self-Image for Children with Cochlear Implants (PASI), an adaptation of the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children (Harter & Pike 1984), indicated that most of them maintained a good self-image and perceived themselves to be competent socially. Parental responses on the Meadow-Kendall Social Emotional Assessment Inventory for Deaf and Hearing Impaired Students (Meadow-Orlans 1983) indicated that the children were emotionally and socially well adjusted. Data indicated no greater adjustment difficulties in children who spent more time in mainstream classrooms than in those children who were in special education classrooms and no difference between children who relied on speech exclusively for communication and those who used both speech and sign to communicate. Children who were in classrooms that emphasized OC had more intelligible speech (Tobey et al. 2003) and fewer communication breakdowns (Tye-Murray 2003) than those placed in classrooms that used both speech and sign.

The relatively good psychosocial adjustment of this group must be considered in light of possible sources of sample selection bias. All families whose child met the criteria were invited to participate in the study, and the sample was large and geographically diverse. However, only those families who volunteered to participate could be included, and volunteers may not be as representative a sample as might be achieved through random assignment. Although all expenses were paid to attend the testing sessions, less affluent families and those children who are poor performers or exhibit adjustment problems may be less likely to assent to testing. In addition, most of the participating children came from two-parent families with well-educated and informed parents, as these parents were among the first in North America to seek out cochlear implantation when their children were very young. These parents were likely to be supportive of their child’s personal and social development. Children with additional significant disabilities were not included in the sample. Any or all of these factors could result in better psychosocial skills than might be measured in the general population of children with hearing loss. However, all studies of this type that rely on subjects to volunteer for participation include children and families who self-select to some degree.

Aims of This Study

The primary aims are to (1) determine the extent to which the strong psychosocial skills documented for this group in elementary grades were maintained into high school; (2) assess the extent to which long-term CI users identified with the Deaf community or the hearing world or both; (3) examine the association between group identification and the student’s sense of self-esteem, preferred communication mode, and spoken language skills; and (4) describe the extracurricular world of the teenagers who were mainstreamed with hearing age-mates for most of their academic experience, by documenting their participation in clubs, activities, and jobs outside of the school day.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Participants

High school students with long-term CI use (CI-HS) were recruited for this study from a larger sample of 181 participants in a previous research study conducted between 1996 and 2000 when they were in early elementary grades (CI-E). A total of 112 teenagers from the previous study returned for testing between 2004 and 2008, and 21 teenagers who did not return completed questionnaires for the study. The 112 adolescents who returned for follow-up testing had significantly higher speech perception, speech intelligibility, and reading scores when they were in elementary grades than those 72 students who did not return. However, follow-up participants did not differ from nonparticipants in family socioeconomic status (SES) (an SES value was derived by combining highest parent education level with family income category), Performance Intelligence Quotient on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-III (Wechsler 1991), or parent ratings from the Meadow-Kendall Social-Emotional Assessment Inventory for Deaf and Hearing-Impaired Students (Meadow-Orlans 1983) at the CI-E test session. A detailed comparison of the characteristics of those who did and did not return for follow-up testing as teenagers is presented elsewhere in this issue (Geers et al. in press).

Different subgroups were included for the various questionnaires presented in this article. Background information for each subgroup and the mean scores obtained at the CI-E evaluation are summarized in Table 1 to establish the comparability of these samples. Available characteristics are also presented for a normal-hearing control group. The subgroups of respondents consist of the following:

On-site participants—full CI-HS sample: This sample of 112 high school students traveled to St. Louis to participate in a comprehensive battery of tests (Geers et al. in press). They ranged in age from 15.0 to 18.5 yrs at the time of testing. Grade placement of the CI-HS group ranged from 9th to 12th grades, with the majority of the participants enrolled in 10th and 11th grades. Thirty of the CI-HS students (26%) reported using speech and sign to communicate, and 82 students (73%) reported that they seldom or never used sign.

On-site participants—partial CI-HS sample: Of the 112 on-site CI-HS participants described above, a partial sample consisting of 86 completed two of the questionnaires that were added to the test battery in 2005. Comparison of characteristics of the partial sample with those of the full sample at CI-E indicates striking similarity. The proportion of students reporting using speech and sign for communicating (26%) was also similar to that reported for the entire sample of 112.

Off-Site: Seventy-two subjects from the original CI-E sample did not participate in on-site testing. Twenty-three of these had moved without providing a forwarding address. Questionnaires were mailed to the 49 nonparticipants for whom current addresses were available, and $50 was offered for completing and returning the questionnaire packet. Sample characteristics reported in Table 1 indicate that nonparticipants were older than the CI-HS participants, because the mailing did not take place until the end of the study. Twenty-one of these students responded (off-site participants). Six of these off-site participants reported using speech and sign to communicate, and one student reported using only sign, so sign use was somewhat higher in the off-site group (33%) than in either on-site group. Mean data for the 28 students who did not return a questionnaire are presented in Table 1 for purpose of comparison. Nonresponders at CI-HS tended to have lower intelligence quotient, speech perception, and language scores at the CI-E test session than both on-site and off-site participants.

Normal-hearing controls: A control group of 46 high school students from the St. Louis metropolitan area who had normal hearing (NHC-HS) were recruited by distributing flyers at church and neighborhood functions. Students were offered $50 for participating in a 3-hr battery of tests and questionnaires. They were similar to the CI-HS group (see Table 1) in age at test and highest parent education. Their intelligence level, estimated with the standard score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn 2007), was 109.6, which was significantly higher than the mean Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-III Performance Intelligence Quotient score (103.1) in the CI-HS group (t[1, 155] = −2.4, p < 0.02), suggesting that the NHC-HS group might be more cognitively/developmentally advanced than the CI-HS group. Reading levels were estimated with two subtests of the Test of Reading Comprehension (TORC)-3 (Brown et al. 1995) and General Vocabulary and Paragraph Comprehension. Mean scaled scores were close to the average for the normative group (i.e., 10), indicating that the NHC-HS group was fairly typical academically.

TABLE 1.

Sample demographics

| CI-HS Full Sample (n = 112) |

CI-HS Partial Sample (n = 86) |

Off-Site Response (n = 21) |

Off-Site No Response (n = 28) |

NH Control Group (n = 46) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 16.7 (0.6) | 16.8 (0.7) | 19.6 (1.5) | 20 (1.0) | 16.6 (0.8) |

| Female (%) | 53 | 51 | 48 | 43 | 52 |

| Parent education (yrs) | 15.8 (2.5) | 15.7 (2.5) | 16.5 (2.5) | 15.4 (2.5) | 16.9 (2.3) |

| Age at onset (mos) | 3.8 (8.5) | 2.6 (6.9) | 3.1 (9.1) | 7.7 (10.3) | — |

| Age at CI (yrs) | 3.41 (0.9) | 3.36 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.9) | — |

| PIQ | 103 (14) | 103 (13) | 103 (15) | 99 (16) | — |

| LNT % correct | 51 (25) | 53 (24) | 54 (28) | 30 (29) | — |

| TACL standard score | 85 (19) | 85 (18) | 83 (20) | 74 (23) | — |

LNT, Lexical Neighborhood Test; PIQ, performance intelligent quotient; TACL, Test for Auditory Comprehension of Language.

Materials

Psychosocial function was assessed by asking the participants, and their parents, about the CI-HS student’s social skills, group identification, and self-esteem. For adolescents receiving the entire battery of assessments, the academic vocabulary subtests of the TORC (Brown et al. 1995) provided a measure of how the students were doing in their academic subjects. We describe the questionnaires completed by either the CI-HS participant or their parents in the subsequent section.

Social skills • Standardized norm-referenced questionnaires were completed by the full sample of 112 participants and their parents (The Social Skills Rating System, Gresham & Elliott 1990). These measures provide multirater assessments of student social behaviors. Items sample socially acceptable learned behaviors that enable a person to interact effectively with others and avoid socially unacceptable responses. Sharing, helping, initiating relationships, requesting help, giving compliments, and saying “please” and “thank you” are examples of social skills. The component scales document the student’s development of social competence, peer acceptance, and adaptive functioning at school and at home. Three behavior rating forms are available (teacher, parent, and student). This investigation used two of these forms—parent and student ratings. The forms are appropriate for students in grades 7 through 12. The student rating form includes 39 statements to which students respond: Never, Sometimes, or Very Often. Examples of the items are “I make friends easily.” “I try to understand how my friends feel when they are angry, upset, or sad.” “I accept punishment from adults without getting mad.” “I tell other people when they have done something well.” Gender-specific national norms are provided on a diverse sample (multiracial, handicapped, and nonhandicapped) of >4000 children. The student and the parent rating forms assessed the following common core behaviors:

Cooperation • This scale included compliant behaviors, such as helping others, sharing materials, and following rules and directions.

Assertion • This scale included assertive behaviors like asking others for information, introducing oneself, and responding to the actions of others, such as peer pressure or insults.

Self-Control • This scale included behaviors that emerge in conflict situations (e.g., responding appropriately to teasing) and in nonconflict situations requiring taking turns or compromising.

The Student form also measures empathy for others (e.g., behaviors that show concern and respect for others feelings and viewpoint). The Parent form also measures responsibility (e.g., behaviors that demonstrate ability to communicate with adults and regard for property or work). The Parent form also measured behaviors that might interfere with the acquisition of social skills (i.e., problem behaviors), which are rated according to their perceived frequency. These measures included the following:

Externalizing Problems • Inappropriate behaviors involving verbal or physical aggression toward others, poor control of temper, and arguing.

Internalizing Problems • Behaviors indicating anxiety, sadness, loneliness, and poor self-esteem.

Self-esteem • Questionnaires assessing group identification and self-esteem were introduced during the second year of data collection; thus, they are available for a partial sample of 86 adolescents who participated in the on-site study and 21 CI-HS off-site participants who mailed in their questionnaires. These questions were also completed by the 46 NHC-HS students. The self-esteem scale (jambor & Elliott 2005) consisted of statements that a student rated using a 4-point response format ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Previous studies demonstrated a positive association between self-esteem and overall psychological well-being. Self-esteem has been linked with academic achievement and the ability to cope with stressful life events. Self-esteem also has been shown to have an impact on motivation, emotion, and behavior (Rosenberg 1979; Rosenberg et al. 1995). The 10 self-esteem items included statements such as “I feel that I have a number of good qualities.” “All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure.” “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” The 4-point ratings were rescaled to a consistent direction, where 4 reflected the most positive self-esteem and 1 reflected the most negative self-esteem rating. Median ratings were used to summarize overall self-esteem.

Group identification • The Group Identification Scale (Jambor & Elliott 2005) was administered to 86 of the CI-HS students who participated in the on-site study and 21 CI-HS off-site participants who mailed in their questionnaires. Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with a set of six statements that were indirectly or directly related to their contact with deaf or hearing individuals (e.g., “Relationships with other deaf people are important to me”) on a 4-point scale ranging from “completely untrue” (1) to “completely true” (4). This scale included items such as “I go to events where the majority of people are hearing.” “I am involved in the life of a Deaf community.” “I do not have problems interacting with hearing people.” Group identification ratings were rescaled for the analysis, so that high ratings (i.e., 4) reflected identification with the hearing community and low ratings (i.e., 1) reflected identification with the Deaf community.

Student experiences questionnaire • A student questionnaire was administered to all 112 of the CI-HS students who participated in the on-site study, 21 CI-HS off-site participants who mailed in their questionnaires and 46 NHC-HS students. Questions were designed to assess issues with regard to school and friendships. Students were asked to list extracurricular activities and sports in which they participated outside of the school day and any jobs they had held during the summer or after school. These were summarized in relation to the required communication skills.

Reading comprehension • Three supplementary subtests of The Test of Reading Comprehension (Brown, Hammill & Wiederholt 1995) were administered to the full sample of 112 CI-HS students who participated in the on-site study. These results indicate how CI-HS students compared with hearing age-mates in three content areas: Social Studies, Mathematics, and Science.

RESULTS

The Social Skills Rating System

Standard scores estimate social skills in relation to gender and age-matched students in the normative sample of typically developing adolescents (mean = 100; SD = 15) (Gresham & Elliott 1990). As a group, the CI-HS students scored within 1SD of the mean for normative sample of typically developing students on both the Parent Rating Scale (mean = 105.3; SD = 15.3) and the Student Rating Scale (mean = 104.7; SD = 13.9). The Problem Behavior mean score also was within the average range (mean = 98.5; SD = 12.8).

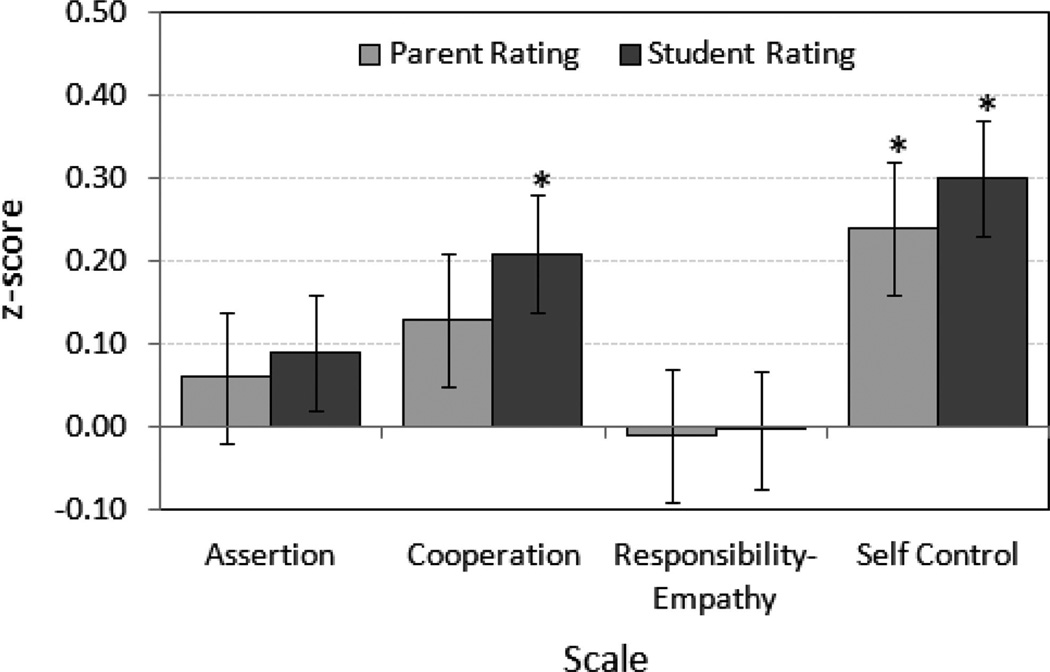

Standard scores are not provided for individual subscale scores; therefore, raw scores on each subscale were converted to z scores based on raw data provided in the test manual for the appropriate age-gender normative group. A z score of 0 corresponds to the mean of the comparison normative group; positive z scores indicate that the CI students exhibit more social skills than the average for the standardization sample, and negative z scores indicate fewer social skills than the average. Figure 1 depicts average ratings for the CI group on the three social skills assessed on both Parent and Student Rating Scales, as well as the separate scores on the Responsibility scale (parent rating) and Empathy scale (student rating). On the parent rating form, average ratings for Assertion, Responsibility, and Empathy were similar to the age and gender-matched normative sample (i.e., mean scores did not differ significantly from zero). Student ratings indicated significantly greater cooperation behaviors than in the normative sample (girls: t[58] = 2.2, p < 0.03; boys: t[52] = 2.4, p < 0.02). In addition, significantly more self-control behaviors were noted in the CI-HS sample than the normative sample, an observation evident in the parent rating form (girls: t[56] = 2.1, p < 0.04; boys: t[52] = 2.3, p < 0.03) and the student rating form (girls: t[52] = 2.6, p < 0.01). When parent and student ratings were compared for the three core scales (cooperation, assertion, and self-control), there was no significant difference between z scores obtained from parent and student raters. According to their parents, CI-HS students exhibited social skills that were similar to or better than their age-mates in the standardization sample. These positive findings were replicated in the students’ assessments of their own social behaviors; students rated themselves as being more cooperative and self-controlled than age and gender-matched adolescents in the normative sample. Analysis of Problem Behaviors ratings indicated that female CI adolescents reported significantly fewer internalizing problems than the normative sample (t[58] = −2.7; p < 0.01), and male adolescents reported significantly fewer externalizing problems than the normative sample (t[52] = −4.27, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

Mean ratings of 112 CI-HS students on the parent rating form and the student rating form of the Social Skills Rating Scale converted to a z score based on norms for typically developing (NS-TD) age mates. Error bars indicate SDs, and asterisks indicate means that are significantly higher (indicating better social skills) than the NS-TD: cooperation student rating (t[1,111] = 3.25; p < 0.002); self-control parent rating (t[1,108] = 3.09; p < 0.003); student rating (t[1,111] = 4.03; p < 0.0001).

Parent ratings on the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) were consistent with ratings obtained from these parents on the social skills subtest of the Meadow-Kendall Social-Emotional Adjustment Inventory (Meadow-Orlans 1983) some 8 yrs earlier when their children were 8 or 9 yrs old (Nicholas & Geers 2003). At that time, the average parent rating for the 112 on-site follow-up participants was 3.26 points (SD = 0.41), where 4.0 is the most well adjusted and 1.0 is the least well adjusted. The correlation between parent ratings on the Meadow-Kendall Social-Emotional Adjustment Inventory at CI-E and those obtained on the SSRS at CI-HS was 0.44, which was statistically significant (z[1,106] = 4.85; p < 0.001).

Self-Esteem

Twenty-five percent of the CI-HS on-site participants (N = 22) assigned themselves the highest rating (i.e., 4) on all 10 self-esteem items. Sixty-two percent (N = 53) assigned a median rating between 3 and 3.5. The remaining 13% (N = 11) had median ratings of 2 or 2.5, reflecting lower self-esteem. More of the CI-HS on-site participants reported low self-esteem than in the NHC-HS group, where only 2 of the 46 students (4%) assigned median ratings of 2 or 2.5. Thirty-two of the NHC-HS group (70%) assigned themselves the highest rating (i.e., 4) on all 10 items (compared with 25% of the CI-HS sample). One hundred percent of the 21 CI-HS off-site participants who did not attend a research camp and mailed in their questionnaires assigned themselves a median rating of ≥3.

Self-esteem ratings were compared with self-ratings obtained from these same students at the CI-E evaluation when they were 8 or 9 yrs old on the PASI (Nicholas & Geers 2003). At that time, their average self-rating ranged from 3.47 (SD = 0.41) on the school self-image scale to 3.65 (SD = 0.39) on the physical self-image scale (with 1.0 = the poorest self-image and 4.0 = highest self-image).

Group Identification

The group of CI-HS students was evenly divided between hearing, deaf, and mixed identification. Twenty-six of the 86 CI-HS students (30%) provided median ratings <3 and were categorized as identifying with the Deaf community. Twenty-eight of the 86 CI-HS students (33%) provided median ratings of ≥3.5 and were categorized as identifying with the hearing community. For 32 of the 86 CI-HS students (37%), median ratings between 3.0 and 3.4 indicated mixed identification with both the Deaf and hearing communities. The group of CI-HS students who completed questionnaires off-site and did not participate in the research camp experience showed a higher proportion who identified with the hearing community: deaf identification (29%), hearing identification (43%), and mixed identification (29%). When the on-site and off-site respondents are combined, 70% expressed identification ratings of ≥3.0, indicating either mixed or hearing group identification.

Table 2 summarizes the average speech perception, speech production, language, and self-esteem scores of CI-HS on-site participants in each group-identification category. There was a significant effect of group identification for speech perception scores (F[2,83] = 4.22, p < 0.02). Fisher’s Protected Least Significance Difference (PLSD) revealed one significant pairwise comparison; teenagers who identified with the hearing identification group were significantly more accurate on the Lexical Neighborhood Test (Kirk et al. 1995) presented at a soft level of 50 dB than the deaf identification group (p < 0.01). A significant effect of group identification was also observed for language scores (F[2,83] = 3.23, p < 0.05). Fisher’s Protected Least Significance Difference post hoc analyses indicated one significant pairwise comparison between the hearing and deaf identification groups. Teenagers who identified with the hearing community had significantly higher Language Content Index scores on the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals - CELF (Semel-Mintz, Wiig & Secord 2003) than the deaf identification group (p = 0.01). There were no significant differences based on group identification for self-esteem ratings. Differences in speech intelligibility scores on the McGarr sentences (Tobey et al. 2010) did not reach statistical significance.

TABLE 2.

Group identification and mean outcome values

| Measure | Deaf Identification |

Mixed Identification |

Hearing Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students | 26 | 32 | 28 |

| Speech perception* | 43.8 | 54.6 | 60.4* |

| Speech intelligibility† | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| Language‡ | 86.4 | 91.4 | 98.9** |

| Self-esteem§ | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

Lexical Neighborhood Test (Kirk et al. 1995): percent correct at 50 dB HL.

McGarr sentences (McGarr 1983): percent intelligible in quiet.

Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (Wigg 2004): Language Content Index.

Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg et al. 1995); rating on a 1 (low) to 4 (high) scale.

Student Experiences

In response to the Student Experiences Questionnaire, 95% of the students reported that they were mainstreamed for more than half of the school day. The majority of CI-HS students (85%) were placed in the appropriate grade for their age. Further analysis of academic vocabulary suggests that this placement was not just “social mainstreaming”—a practice in which students are placed with others of their own age for social reasons. In fact, most teenagers exhibited grade-appropriate knowledge of academic vocabulary as evidenced by their scores on supplementary subtests of the TORC. Table 3 summarizes vocabulary standard scores in terms of current grade placement. More than 80% of the CI-HS students scored within the average range for hearing students in the same grade.

TABLE 3.

TORC academic vocabulary subtests: average standard score by grade

| Content Area | Grades 9–10 (N = 34) |

Grade 11 (N = 54) |

Grade 12 (N = 24) |

All Students (N = 112) |

Percent WNL* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social studies | 9.5 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 92 |

| Mathematics | 8.8 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 91 |

| Science | 8.1 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 81 |

Within normal limits: percentage of students scoring within 1SD (i.e., 2) of the mean score (i.e., 10) of the normative sample of grade-matched students on the Test of Reading Comprehension (TORC) (Brown et al. 1995).

Almost all students (98%) reported having hearing friends, and a majority (79%) of the respondents reported having deaf friends. More than 75% of the teenagers reported that they use spoken language with the general public, with little or no difficulty either in understanding what is said to them or in being understood. Many of these students stated good spoken language skills enabled them to participate with their high school classmates in activities in their schools and communities and that being able to communicate using spoken language was valuable for academic work in school and for their after-school jobs.

Understanding spoken language also contributes to interaction with hearing students. A majority (72%) of students reported that they conversed on the telephone, at least with familiar people; 55% of the teenagers reported understanding much of what is said on television without captioning; 47% of the students reported that they did not use speaking or signing interpreters or captioning in their classes, and 64% of the group reported using primarily speech (without sign) to communicate. These findings are similar to those reported by Wheeler et al. (2007) in which 69% of adolescents with CIs used spoken language as their preferred mode of communication and to those reported by Uziel et al. (2007) in which 79% of children with >10 yrs of CI experience reported using the telephone.

Extracurricular Activities, Sports, and Jobs

Almost all of the students (94%) were active participants in high school activities and sports. Half of the teenagers held jobs. Only 4% of the CI-HS on-site participants failed to identify an activity, sport, or job with which they were involved during the school day or after school hours. Teens reported a wide range of extracurricular activities, sports, and jobs that would be typical of most high school students. Examples of the most frequent activities, sports, and jobs reported by CI-HS participants are provided in Table 4. Table 5 compares the percentage of students responding in each category in the NHC-HS group with the two CI-HS groups (on-site participants and off-site participants). The activities, sports, and jobs in which the 46 normal-hearing participants were involved resembled those reported by the CI-HS participants. There was no significant difference in family SES ratings for students who held jobs and students who did not hold jobs in either the CI-HS or the NHC-HS groups. There was no significant difference in Lexical Neighborhood Test speech perception scores for CI-HS students who held jobs (mean = 58% correct; SD = 24) and those who did not hold a job (mean = 62% correct; SD = 23).

TABLE 4.

Sports, activities, and jobs of CI participants

| Individual Sports | Team Sports | Clubs/Activities | Clubs/Activities | Jobs | Jobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowling | Baseball | Band | Peer ministry | Art shop worker | Landscaping |

| Cycling | Basketball | Boys and girls club | SADD | Baby sitter | Library |

| Dance | Cheerleading | Chess club | Science club | Camp counselor | Lifeguard |

| Figure skating | Cricket | Deaf club | Scouts | Cashier | Mowing yards |

| Golf | Curling | Drama club | Sign language club | Child care | Pizza Pub |

| Marshall arts | Field Hockey | FAA | Space camp | Cleaner | Photography production assistant |

| Motocross racing | Football | 4-H club | Spanish club | Cook | Ranch hand |

| Skiing | Hockey | French club | Student council | Data entry | Retail sales |

| Surfing | Lacrosse | Girl guides of Canada | West Point Youth Council | Dishwasher | Scorekeeper |

| Tennis | Polo Cross | Habitat for humanity | Yearbook | Factory worker—chocolate | |

| Track | Rugby | International club | Young democrats | Farm hand | Theater group |

| Weight training | Soccer | Key club | Young republicans | Fast food restaurant | Teacher assistant summer school |

| Wrestling | Volleyball | Journalism club | Youth group | Figure skating teacher | Tutoring |

| Magic club | Zoology club | Grocery-bag, stock, register | Warehouse worker | ||

| Laborer | Veterinarian clinic |

TABLE 5.

Extracurricular activities: percentage of students with jobs, hobbies, and playing sports

| Group | Jobs | Sports | Hobbies |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHC-HS (n = 46) | 48 | 91 | 89 |

| CI-HS on-site participants (n = 112) | 54 | 81 | 91 |

| CI-HS off-site participants (n = 21) | 65 | 80 | 90 |

DISCUSSION

Results are discussed as they address the primary aims listed in the Introduction section:

Objective 1: Determine the Extent to Which the Strong Psychosocial Skills Documented in Elementary Grades Were Maintained into High School

Parent ratings of their children’s social adjustment were stable over time, with a significant correlation between Meadow-Kendall ratings at CI-E and SSRS ratings at CI-HS. Average ratings were close to the ceiling at both sessions, indicating that, in general, parents perceived that their children were socially well adjusted. There was also a lack of correspondence between self-ratings and parent ratings of psychosocial adjustment when the students were in elementary grades (Nicholas & Geers 2003). Nevertheless, average self-ratings within this group were high at both the CI-E and CI-HS test sessions, indicating a positive self-image throughout the school years.

Objective 2: Assess the Extent to Which Long-Term CI Users Identified With the Deaf Community or the Hearing World or Both

Seventy percent of the CI-HS students who responded to questions regarding their group identification expressed either strong identification with the hearing community (32%) or mixed identification with both deaf and hearing communities (38%). These results are consistent with earlier findings that adolescents with CIs exhibited a greater hearing identity than those without implants (Wald & Knutson 2000). These CI students interacted with hearing individuals for the bulk of their time in high school, both in school and out of school. Long-term experience in a mainstream setting throughout most of their elementary and high school years likely contributed to their perceptions of becoming comfortable in the hearing world. Feelings of isolation, with accompanying loneliness and lower self-esteem, experienced by previous generations of deaf individuals, was not prevalent in this group.

Objective 3: Examine the Association Between Group Identification and the Student’s Sense of Self-Esteem, Preferred Communication Mode, and Spoken Language Skills

Responses from this group of students represent a significant change from previous reports describing how teens with SNHL viewed themselves and their comfort in the hearing world before the advent of CIs. Previous reports maintain use of sign language and identification with the Deaf community significantly contributes to positive self-esteem in children with severe-profound SNHL (Jambor & Elliott 2005). However, in the current sample, the majority of the CI-HS students used spoken language as their primary means of communicating but exhibited high levels of self-esteem. Results are consistent with other studies of CI adolescents, indicating that an increase in hearing identity was not associated with personal or social adjustment problems (Wald & Knutson 2000). Those CI-HS students who achieved higher speech perception scores and language scores closest to those of hearing age-mates were most likely to identify strongly with the hearing world. It is likely that strong OC skills facilitated identification with a hearing peer group.

Objective 4: Describe the Extracurricular World of the Teenagers Who Were Mainstreamed for Most of Their Academic Experience, by Documenting Their Participation in Clubs, Activities, and Jobs Outside of the School Day

These CI students for the most part were full participants in their high schools, academically and socially. Involvement in extracurricular activities is an important part of the high school experience and provides opportunities for socialization and independence. CI-HS teens were involved in after-school and summer jobs that were similar to those reported by the control group of normal-hearing teenagers. Part-time jobs provide adolescents with experiences to help them acquire self-confidence and develop self-reliance. CI-HS students capitalized on these opportunities to the same extent as their hearing peers. Students with CIs held jobs that required communicating with the public as well as jobs that posed limited communication demands. Their employment rate was also similar to that reported nationwide for teenagers. Previous data from 2004 to 2007 from the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor indicate the percentage of 16- to 19-yr-olds holding jobs in the U.S. ranged from 41.3 to 43.9% (data.bls.gov/PDQ/servlet/SurveyOutputServlet) compared with 50% for the CI-HS group. There was no difference in family SES for employed versus unemployed students in either the CI-HS sample or the hearing control group.

CONCLUSIONS

Data reported elsewhere in this issue indicated prelingually deaf children who received a CI at an early age achieved greatly improved speech intelligibility (Tobey et al. in press) and English language competence (Geers & Sedey in press) between elementary grades and high school, with many reaching age-appropriate language levels compared with hearing teenagers. These achievements exceeded spoken language skills in comparable groups of students documented before the advent of CIs (Geers & Moog 1989) and likely influenced the lives and attitudes of these CI teens who at high school age demonstrated strong social skills, high self-esteem, and strong identification with the hearing world. However, the individuals in this study had some characteristics that may not be representative of the entire population of children receiving CIs, and our conclusions are tempered by these considerations.

From the beginning, these hearing families were highly motivated for their child to use speech to communicate. In fact, 96% of the parents of children in the larger CI-E sample stated that they chose an implant for their child so that she or he would have a chance to become part of the hearing world (Nicholas & Geers 2003). This characteristic differentiates the sample from a more general population of children with SNHL, particularly families with deaf parents, and certainly could have contributed to the large proportion identifying with the hearing rather than the Deaf community. In addition, the 112 students who returned for follow-up testing outperformed the 72 students who did not return for follow-up on some outcome measures at CI-E (Geers et al. in press). Some of the teenagers who declined to participate may have done so because they either were no longer using the CI or did not achieve the level of outcomes they or their family had hoped. Among those students who did not return for testing at CI-HS, those completing a mailed packet of questionnaires exhibited higher scores at the CI-E test session than those who failed to complete the questionnaires. These sample selection factors may have skewed our results. We are therefore cautious about overestimating the impact of long-term use of CIs on the psychosocial development of deaf individuals and overgeneralizing these results to the general population.

On the other hand, these results may underestimate the potential effects of early cochlear implantation on psychosocial function in current CI users. Advances in implant technology, along with revised candidate selection guidelines that include children younger than 2 yrs and those with greater amounts of preimplant residual hearing, have been associated with even larger numbers of children achieving age-appropriate spoken language skills as early as kindergarten (Nicholas & Geers 2007; Geers et al. 2009). As the current population of CI children with these advantages reaches adolescence, even more of them may find a sense of acceptance, belonging, and high self-esteem in the hearing world.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the grant RO1 DC000581 from National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

REFERENCES

- Antia SD. Social interaction of partially mainstreamed hearing-impaired children. Am Ann Deaf. 1982;127:18–25. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bat-Chava Y, Deignan E. Peer relationships of children with cochlear implants. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2001;6:186–199. doi: 10.1093/deafed/6.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bat-Chava Y, Martin D, Kosciw JG. Longitudinal improvements in communication and socialization of deaf children with cochlear implants and hearing aids: Evidence from parental reports. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:1287–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R, Knutson J, Dahlstrom A. Social interaction of pediatric cochlear implant recipients with age-matched peers. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:105–109. doi: 10.1177/0003489400109s1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VL, Hammill DD, Wiederholt JL. Test of Reading Comprehension. 3rd ed. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon R, Greenberg M. Social and Emotional Development of Deaf Children. In: Marschark M, Spencer P, editors. Deaf Studies, Language and Education. Washington DC: Gallaudet University; 2003. pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson E, Strong M, Gold R. How successful deaf teenagers experience and cope with isolation. Am Ann Deaf. 1992;137:261–270. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Dunn L. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 4th ed. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geers A. Performance Aspects of Mainstreaming. In: Ross M, editor. Hearing Impaired Children in the Mainstream. Parkton, MD: York Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Brenner C. Background and educational characteristics of prelingually deaf children implanted by five years of age. Ear Hear. 2003;24:2S–14S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051685.19171.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Brenner C, Tobey E. Long-term outcomes of cochlear implantation in early childhood: Sample characteristics and data collection methods. Ear Hear. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182014c53. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Moog JS. Factors predictive of the development of literacy in hearing-impaired adolescents. Volta Rev. 1989;91:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Moog JS, Biedenstein J, et al. Spoken language scores of children using cochlear implants compared to hearing age-mates at school entry. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2009;14:371–385. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enn046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Sedey A. Language and verbal reasoning skills in adolescents with 10 or more years of cochlear implant experience. Ear Hear. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181fa41dc. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Pike R. The pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance for young children. Child Dev. 1984;55:1969–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambor E, Elliott M. Self-esteem and Coping Strategies Among Deaf Students. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2005;10:63–81. doi: 10.1093/deafed/eni004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk K, Pisoni D, Osberger M. Lexical effects of spoken word recognition by pediatric cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 1995;16:225–259. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199510000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluwin T, Stewart D. Cochlear implants for younger children: A preliminary description of the parental decision and outcomes. Am Ann Deaf. 2000;145:26–32. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson JF, Stika CJ. Psychological Consideration in Pediatric Cochlear Implantation. In: Eisenberg LS, editor. Clinical Management of Children with Cochlear Implants. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; 2009. pp. 367–411. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh I, Maxwell-McCaw D, Bat-Chava Y, et al. Correlates of psychosocial adjustment in deaf adolescents with and without cochlear implants: A preliminary investigation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2009;14:244–259. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enn038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschark M, De BR, Polazzo MG, et al. Deaf and hard of hearing adolescents’ memory for concrete and abstract prose. Effects of relational and distinctive information. Am Ann Deaf. 1993;138:31–39. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarr NS. The effect of context on the intelligibility of hearing and deaf children's speech. Lang.Speech. 1981;24:255–264. doi: 10.1177/002383098102400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadow-Orlans K. Meadow-Kendall Social Emotional Assessment Inventory for Deaf and Hearing Impaired Students. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University; 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman C, Mootilal A, Mackay S. The social adjustment of deaf adolescents in segregated partially integrated and mainstreamed settings. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 1996;1:52–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas J, Geers A. Personal, social, and family adjustment in children with early cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 2003;24:69S–81S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051750.31186.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas J, Geers A. Will they catch up? The role of age at cochlear implantation in the spoken language development of children with severe-profound hearing loss. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50:1048–1062. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/073). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M, Schooler C, Schoenbach C, et al. Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, different outcomes. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer B. Psychological, Social and Educational Dimensions of Deafness. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. Psycho-Social Aspects of Mainstreaming. In: Ross M, editor. Hearing-Impaired Children in the Mainstream. Parkton, MD: York Press; 1990. pp. 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tobey E, Geers A, Brenner C, et al. Factors associated with development of speech production skills in children implanted by age five. Ear Hear. 2003;24:36S–45S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051688.48224.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobey E, Geers A, Sundarrajan M, et al. Factors influencing speech production in elementary and high-school aged cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181fa41bb. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye-Murray N. Conversational fluency of children who use cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2003;24:82S–89S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051691.33869.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uziel AS, Sillon M, Vieu A, et al. Ten-year follow-up of a consecutive series of children with multichannel cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:615–628. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000281802.59444.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald R, Knutson J. Deaf cultural identity of adolescents with and without cochlear implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:87–89. doi: 10.1177/0003489400109s1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler A, Archbold S, Gregory S, et al. Cochlear implants: The young people’s perspective. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12:303–316. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]