Abstract

Purpose

To delineate the effect of COPD on a broad range of valued life activities (VLAs), compared to effects of other airways conditions.

Methods

We used cross-sectional data from a population-based, longitudinal study of U.S. adults with airways disease. Data are collected by telephone interview. VLA disability was compared among 3 groups defined by reported physicians’ diagnoses: COPD/emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to identify independent predictors of VLA disability.

Results

About half of individuals with COPD were unable to perform at least one VLA; almost all reported at least one VLA affected. The impact among individuals with chronic bronchitis and asthma was less, but still notable: 74–84% reported at least one activity affected, and about 15% were unable to perform at least one activity. In general, obligatory activities were the least affected. Symptom measures and functional limitations were the strongest predictors of disability, independent of respiratory condition.

Conclusion

VLA disability is common among individuals with COPD. Obligatory activities are less affected than committed and discretionary activities. A focus on obligatory activities, as is common in disability studies, would miss a great deal of the impact of these conditions. Because individuals are often referred to pulmonary rehabilitation as a result of dissatisfaction with ability to perform daily activities, VLA disability may be an especially relevant outcome for rehabilitation.

Keywords: disability, functioning, COPD, asthma, valued life activities

Much research has focused on disability in COPD, particularly in basic activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and work, or on specific physical functions, such as walking and stair climbing.1–5 However, as opposed to this relatively narrow spectrum, COPD often intrudes on abilities to perform a wide range of activities.6, 7 This study aimed to delineate effects of COPD on a broad range of life activities, compared to the effects of other respiratory conditions representing a gradient of severity.

Assessments that focus on ADLs, IADLs, and mobility ignore much of daily life, yet the ability to perform a wide range of life activities is important to individuals. In a qualitative study, individuals with COPD consistently acknowledged disappointment in the need to give up valued activities, particularly when replacing active leisure activities with passive ones and reducing their overall level of activity.8 Consistent with this, compared to basic ADL-type activities, functioning in valued life activities (VLAs) appears to be more strongly linked to satisfaction with function, psychological well-being, and quality of life.9–15 The American Thoracic Society recommends ability to perform daily activities as an important outcome for pulmonary rehabilitation because individuals are often referred to rehabilitation because they are dissatisfied with those abilities16. Thus, a brief assessment focusing on functioning in a wide range of life activities relevant to individuals with COPD and other respiratory conditions could provide much needed information on disability and may also provide a more sensitive gauge of the true impact of respiratory disease on daily life.

This paper presents an assessment of disability in a wide range of VLAs among individuals with COPD and other respiratory conditions – chronic bronchitis and asthma – and identifies factors associated with such disability. We hypothesized that VLA disability would be greatest among individuals with COPD.

Verbrugge’s model of the “disablement process” provides the theoretical underpinning for measurement of VLA disability.17–19. This model distinguishes between functional limitations, defined as restrictions in performing generic, fundamental physical and mental actions used in daily life in many circumstances (e.g., limitations in walking speed), and disability, defined as difficulty performing activities of daily life (e.g., difficulty in shopping that may result from a limitation in walking speed). The model also recognizes the wide spectrum of life activities, and proposes three categories of activities -- obligatory, committed, and discretionary. Obligatory activities are required for survival and self-sufficiency, including ADL-type activities such as hygiene and self-care, walking inside, walking outside, and using transportation or driving. Committed activities are associated with one’s principal productive social roles, such as paid work, household responsibilities, and child and family care. Discretionary activities include socializing, leisure time activities and pastimes, or other activities that individuals engage in for relaxation and pleasure. We expected that disability would be greater in discretionary and committed activities than in obligatory activities because the former are often more physically demanding and can also be relinquished in order to preserve strength or energy to perform obligatory activities associated with independent functioning.20

METHODS

Sample

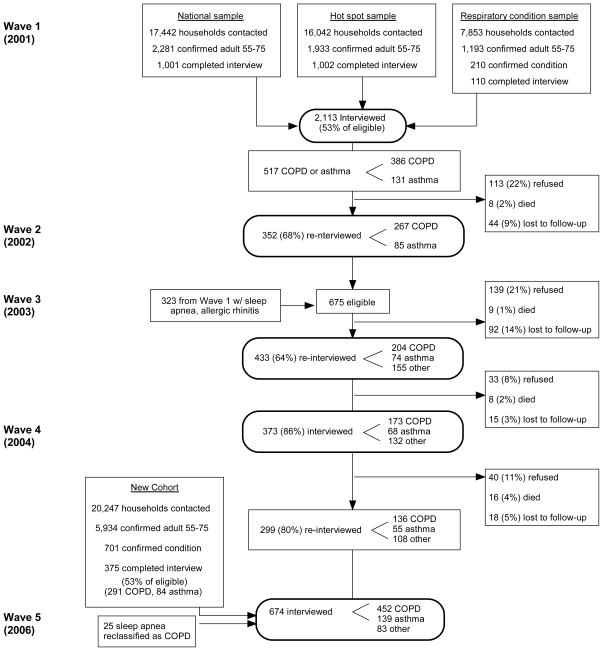

We used cross-sectional data from a single wave of a population-based, longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults with various airways diseases.21 During recruitment, subjects were asked if they had ever been diagnosed with chronic bronchitis, emphysema, COPD or asthma by a medical doctor; if so, they were included in the airways disease cohort. Annual retention among the original sample has averaged approximately 80% through 2006, over five telephone interviews approximately 18 months apart. (See Figure 1.) In 2006, another 375 individuals were recruited from northern California using the original recruitment method, for a total sample size of 675 in 2006. Of the total, 243 reported either COPD or emphysema, 209 reported chronic bronchitis without concomitant COPD or emphysema, and 139 reported asthma only. We defined three non-overlapping respiratory condition groups – COPD/emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma -- based on these self-reported physician diagnoses. The study was approved by the University’s Committee on Human Research.

Figure 1. Recruitment and retention of airways disease cohort.

Recruitment and retention of airways disease cohort through Wave 5 (2006; data used for current study).

Variables

Valued life activity (VLA) disability

The VLA scale originated from a study to determine the impact of arthritis.22 Over the past decade, the VLA scale has been modified and refined, first focusing on rheumatoid arthritis,23 and more recently on respiratory conditions.13, 14 Respondents have been asked over multiple interview waves to identify activities in addition to those queried that are affected by their condition. Revisions have been made based on those accumulated responses as well as analysis of previous versions of the scale.

The VLA scale used in these analyses includes 28 activity domains covering obligatory, committed, and discretionary activities.17–19 Text of the VLA items is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Valued Life Activity Scale Items

| Subscale* | Item |

|---|---|

| O | 1. Taking care of your basic needs, such as bathing, washing, getting dress, or taking care of personal hygiene. |

| O | 2. Walking or getting around inside your home. |

| O | 3. Walking outside, just to get around, in the area around your home or other places you need to go on a regular basis. (This does not include walking for exercise.) |

| O | 4. Getting around your community by car or public transportation. |

| O | 5. Talking on the telephone or in person |

| O | 6. Sleeping. |

| C | 7. Preparing meals and cooking. |

| C | 8. Light housework, such as dusting or laundry. |

| C | 9. Heavier housework, such as vacuuming, changing sheets, or cleaning floors. |

| C | 10. Other work around the house, such as making minor home repairs or working in the garage fixing things. |

| C | 11. Shopping and doing errands. |

| C | 12. Taking care of your children/grandchildren or doing things for them. |

| C | 13. Taking care of other family members, such as your spouse or parent, or other people close to you. |

| C | 14. Household business |

| C | 15. Working at a job for pay |

| D | 16. Gardening or working in your yard. |

| D | 17. Visiting with friends or family members in their home. |

| D | 18. Going to parties, celebrations, or other social events. |

| D | 19. Having friends and family members visit you in your home. |

| D | 20. Participating in leisure activities in your home, such as reading, watching television, or listening to music. |

| D | 21. Participating in leisure activities OUTSIDE your home, such as playing cards or bingo, or going to movies/restaurants. |

| D | 22. Working on hobbies or crafts or creative activities, such as sewing, woodwork, or painting. |

| D | 23. Participating in moderate physical recreational activities, such as dancing, playing golf, or bowling. |

| D | 24. Participating in vigorous physical recreational activities, such as walking for exercise, jogging, bicycling, swimming, or water aerobics. |

| D | 25. Traveling out of town. |

| D | 26. Participating in religious or spiritual activities. |

| D | 27. Doing volunteer work. |

| D | 28. Intimate relations with partner |

O=Obligatory, C=Committed, D=Discretionary

Note: items are not administered in this order.

Assessment of disability with the VLA scale differs from other functional assessments commonly used in COPD. First, measurement focuses only on disability rather than a combination of disability and functional limitations. Second, a wide spectrum of activities is included, based on the underlying theoretical model. Third, the VLA scale takes personal value into account. Activities that are not applicable to an individual (e.g., “taking care of children” if the individual has no children) or not important to the individual (e.g., “cooking” if the spouse does all of the cooking) are not included in scoring the scale. Finally, the VLA scale asks respondents to attribute performance difficulties to the health condition under study. While self-report assessments used in COPD often ask individuals to identify functional problems caused by dyspnea, other disease-related factors, such as systemic symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness that can also contribute to functional difficulties, are typically not assessed.

Respondents rate the difficulty caused by their condition for each of the 28 life activities, (0=no difficulty, 1=a little difficulty, 2=a lot of difficulty, and 3=unable to perform). Activities that participants deem unimportant to them, or that they do not perform for reasons unrelated to their respiratory condition, are not rated or included in scoring. Summary measure scores calculated for the total VLA scale, and for the Obligatory, Committed, and Discretionary subscales include: proportion of activities unable to perform, proportion of activities affected (unable to perform or able to perform but with any level of difficulty), and average difficulty score. Use of proportional measures and mean scores based only on activities that are relevant to an individual permit comparisons among individuals who rated different numbers of activities.

Predictors of VLA disability

Sociodemographic characteristics and measures of disease and health status were examined as potential independent variables associated cross-sectionally with VLA disability. Each of these is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Predictors of VLA Disability

| Variables | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |

| Age | 55–60 years, 61–65 years, 66+ years |

| Sex | |

| Educational level | Less than high school, high school graduation or higher |

| Marital status | Married or living with partner, all other |

| Health behaviors and health status measures | |

| Smoking | Current, former |

| Body mass index (BMI) | Obese (BMI ≥ 30), all other |

| Fatigue | Rating of 0 (no fatigue) to 10 (extremely fatigued) |

| Number of days with respiratory symptoms | Over past 14 days. Responses range from 0 to 14. |

| Number of nights with respiratory symptoms | Over past 14 days. Responses range from 0 to 14. |

| Functional limitations | Difficulty ratings for 10 physical actions such as stooping, getting up from a stooping position, lifting or carrying items, standing in place, standing up after sitting, and walking up and down stairs.29 Items are rated on the same 4-point scale as VLA disability; possible scores range from 0 to 3. |

Analysis

Differences in potential predictor variables among the self-reported respiratory condition groups were tested with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square analyses. Difficulty ratings for each VLA were tabulated by respiratory condition group; means and standard deviations of scale scores were calculated for each group. The proportion of activities that individuals reported affected (or unable) was calculated (e.g., number of obligatory activities affected/total number of obligatory activities rated). Bivariate differences between condition groups were tested with ANOVAs or chi-square analyses. Within the COPD and chronic bronchitis groups, differences in VLA disability by severity were examined. COPD severity was estimated with the COPD severity scale, a validated measure that takes into account symptoms, prior systemic corticosteroid use, other COPD medications, history of intubation and hospitalization, and home oxygen use 24. This severity scale does not include pulmonary function, but has been shown to have good correspondence with forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Each of the 2 groups was divided by its median score on the COPD severity scale, and VLA disability scores compared between the high and low severity groups using t-tests.

Factors independently associated with VLA disability were identified using multiple linear regression analyses including sociodemographic characteristics, health status measures, functional limitations, and respiratory condition (with COPD/emphysema group as the reference). Only results from analyses using the proportion of VLAs affected as dependent variables are shown; other disability scores yielded similar results. For the total VLA difficulty score, four regression models were computed to examine the incremental effects of adding groups of variables. The first model included only sociodemographic variables, the second added health status measures, the third added the functional limitations score, and the fourth added indicator variables for the self-reported respiratory condition. Predictors of Obligatory, Committed, and Discretionary subscale scores were identified in separate analyses.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

The majority of subjects (61.9%) were female and white non-Hispanic (89.7%) (Table 3). Additional characteristics and differences among the conditions groups are shown in Table 3. Most notably, symptom ratings and functional limitations were significantly more pronounced in the COPD group.

Table 3.

Subject Characteristics

| Total (n=591) | COPD, emphysema (n=243) | Chronic bronchitis (n=209) | Asthma (n=139) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | |||||

| Age category, % (n) | .01 | ||||

| •55–60 | 19.1 (113) | 15.6 (38) | 23.0 (48) | 19.4 (27) | |

| •61–65 | 28.8 (170) | 23.5 (57) | 32.1 (67) | 33.1 (46) | |

| •66–80 | 52.1 (308) | 60.9 (148) | 45.0 (94) | 47.5 (66) | |

| Female, % (n) | 61.4 (366) | 57.6 (140) | 65.6 (137) | 64.0 (89) | .19 |

| Married/partner, % (n) | 60.9 (354) | 53.5 (130) | 61.5 (128) | 69.1 (98) | .01 |

| Ethnicity (white, non- Hispanic), % (n) | 89.7 (514) | 91.1 (216) | 90.7 (185) | 85.6 (113) | .21 |

| Less than high school education, % (n) | 8.8 (52) | 11.9 (29) | 6.7 (14) | 6.5 (9) | .08 |

| Health status factors | |||||

| Current smoker, % (n) | 18.1 (107) | ||||

| Former smoker, % (n) | 52.8 (312) | 27.6 (67) | 14.4 (30) | 7.2 (10) | <.0001 |

| 62.1 (151) | 47.4 (99) | 44.6 (62) | |||

| Body mass index | .32 | ||||

| Underweight | 2.5 (15) | 3.7 (9) | 1.4 (3) | 2.2 (3) | |

| Normal weight | 27.8 (164) | 31.3 (76) | 23.0 (48) | 28.8 (40) | |

| Overweight | 35.2 (208) | 32.1 (78) | 40.2 (84) | 33.1 (46) | |

| Obese | 34.5 (204) | 32.9 (80) | 35.4 (74) | 36.0 (50) | |

| Comorbidities, % (n) | .20 | ||||

| 0 | 20.8 (123) | 16.9 (41) | 23.0 (48) | 24.5 (34) | |

| 1 | 32.2 (190) | 30.9 (75) | 32.5 (68) | 33.8 (47) | |

| 2 or more | 47.0 (278) | 52.3 (127) | 44.5 (93) | 41.7 (58) | |

| Fatigue rating, mean (SD) (0 = no fatigue, 10 = very severe fatigue) | 4.5 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.5) | 4.3 (2.5) | 3.9 (2.5) | <.0001 |

| Days with respiratory symptoms in past 2 weeks | 5.4 (5.5) | 7.7 (5.8) | 3.9 (4.6) | 3.6 (4.8) | <.0001 |

| Nights with respiratory symptoms in past two weeks | 2.7 (4.7) | 3.4 (5.4) | 2.5 (4.4) | 1.6 (3.5) | .002 |

| Functional limitations | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.6) | <.0001 |

Prevalence of disability in valued life activities

Activities that individuals perceived as not important or that they did not perform for reasons other than health (e.g., no yard work or gardening because respondent does not have a yard) were not rated. There were no significant differences among the groups in the number of VLAs rated. In each group, an average of 25 VLAs were rated. (See Appendix.)

Appendix.

Percent Affected, Percent Unable, and Mean Difficulty Ratings for Individual Valued Life Activities

| % affected | % unable | Mean (SD) difficulty rating | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. resps* | COPD/emph | Chron bronc | Asth | COPD/emph | Chron bronc | Asth | COPD/emph | Chron bronc | Asthma | |

| Obligatory | ||||||||||

| Car/transit | 579 | 28.4 | 15.6 | 13.3 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.40 (0.73) | 0.20 (0.52) | 0.18 (0.52) |

| Basic needs/self-care | 582 | 30.5 | 15.5 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.43 (0.70) | 0.19 (0.48) | 0.15 (0.44) |

| Talk | 583 | 34.3 | 21.3 | 16.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.41 (0.61) | 0.26 (0.53) | 0.17 (0.40) |

| Walk inside | 581 | 44.4 | 22.3 | 21.3 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.56 (0.70) | 0.26 (0.51) | 0.26 (0.55) |

| Sleep | 581 | 52.3 | 50.7 | 37.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.70 (0.76) | 0.60 (0.65) | 0.47 (0.67) |

| Walk outside | 578 | 58.4 | 36.8 | 30.9 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 0.83 (0.85) | 0.50 (0.74) | 0.42 (0.72) |

| Committed | ||||||||||

| Household business | 569 | 22.3 | 12.9 | 18.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.31 (0.64) | 0.16 (0.48) | 0.23 (0.53) |

| Meals/cook | 564 | 35.8 | 16.3 | 15.9 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.54 (0.83) | 0.23 (0.59) | 0.23 (0.57) |

| Other family care | 503 | 45.0 | 26.9 | 23.5 | 7.9 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 0.77 (0.99) | 0.37 (0.71) | 0.34 (0.68) |

| Light housework | 563 | 49.6 | 29.3 | 25.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.71 (0.83) | 0.42 (0.75) | 0.34 (0.65) |

| Shopping/errands | 580 | 57.6 | 30.6 | 26.5 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.87 (0.88) | 0.39 (0.65) | 0.37 (0.68) |

| Child care | 397 | 59.2 | 32.3 | 31.6 | 10.6 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 1.05 (1.03) | 0.53 (0.82) | 0.50 (0.83) |

| Paid work | 327 | 62.8 | 32.5 | 35.8 | 41.9 | 13.7 | 12.4 | 1.57 (1.36) | 0.66 (1.08) | 0.68 (1.06) |

| Heavy housework | 553 | 68.4 | 51.3 | 44.4 | 11.1 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 1.22 (1.02) | 0.76 (0.87) | 0.64 (0.83) |

| Minor repairs | 462 | 71.3 | 45.6 | 43.6 | 18.8 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 1.30 (1.08) | 0.70 (0.94) | 0.72 (0.97) |

| Discretionary | ||||||||||

| Leisure in | 583 | 10.7 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 (0.38) | 0.06 (0.25) | 0.09 (0.31) |

| Religious/spiritual activities | 525 | 28.1 | 14.2 | 21.6 | 5.7 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.46 (0.85) | 0.18 (0.52) | 0.26 (0.56) |

| Having others visit | 572 | 31.5 | 17.7 | 23.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.40 (0.65) | 0.22 (0.51) | 0.32 (0.64) |

| Hobbies | 511 | 34.1 | 18.0 | 18.3 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.55 (0.89) | 0.27 (0.67) | 0.23 (0.55) |

| Leisure out | 552 | 40.0 | 18.5 | 19.7 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.57 (0.82) | 0.26 (0.61) | 0.27 (0.59) |

| Visiting others | 565 | 41.1 | 22.4 | 25.9 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.58 (0.80) | 0.29 (0.62) | 0.37 (0.70) |

| Travel | 558 | 41.7 | 22.9 | 25.4 | 6.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.65 (0.91) | 0.31 (66.1) | 0.35 (0.69) |

| Volunteer work | 458 | 46.8 | 23.7 | 22.4 | 19.7 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 0.97 (1.20) | 0.38 (0.79) | 0.37 (0.81) |

| Parties/events | 534 | 47.1 | 29.7 | 30.0 | 7.0 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 0.79 (0.97) | 0.38 (0.65) | 0.45 (0.80) |

| Intimate relations | 399 | 54.5 | 26.0 | 25.2 | 15.6 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.98 (1.10) | 0.39 (0.75) | 0.38 (0.75) |

| Gardening | 494 | 75.4 | 52.5 | 51.6 | 18.0 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 1.46 (1.04) | 0.76 (0.89) | 0.78 (0.91) |

| Moderate physical activities | 407 | 69.6 | 43.7 | 41.8 | 28.7 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 1.46 (1.20) | 0.75 (1.01) | 0.77(1.07) |

| Vigorous physical activities | 506 | 85.2 | 59.1 | 61.5 | 31.0 | 10.5 | 6.6 | 1.75 (1.05) | 1.08 (0.95) | 0.95 (0.93) |

Response frequencies vary as a function of the number of participants reporting that the activity either was not important to them or not applicable to them

Affected activity

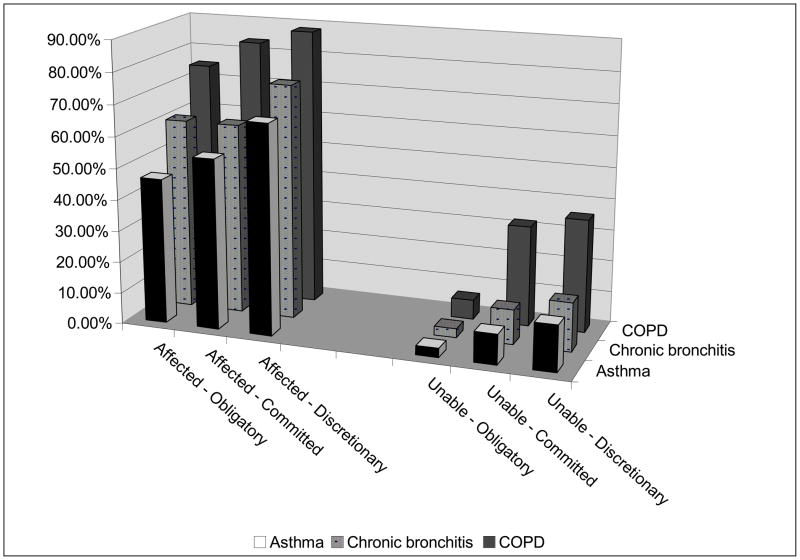

Ninety-four percent of the COPD group reported at least one VLA affected. Smaller proportions of the other groups reported at least one VLA affected (chronic bronchitis, 84%; asthma, 74%), although in each case, the proportion was substantial. For the VLA categories, a significantly greater percentage of the COPD group also reported at least one VLA affected (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of each condition group with at least one VLA affected and proportion unable to perform at least one VLA.

Proportion of the COPD, chronic bronchitis, and asthma groups who reported at least one VLA affected by their condition, and proportion of each group who reported being unable to perform at least one VLA because of their condition.

Except for “Unable, Obligatory,” all differences between groups are statistically significant (p<.0001) by χ2 analysis.

On average, individuals with COPD reported that 46% of the activities important to them were affected by COPD, compared to 28% for those with chronic bronchitis, and 27% for asthma (Table 4). Regardless of which summary score for activities affected was calculated or for which type of activities, individuals with COPD reported significantly greater disability than individuals in the other two groups. Within the COPD and chronic bronchitis groups, individuals with high severity reported a significantly greater proportion of activities affected than individuals with low severity.

Table 4.

Valued Life Activity Summary Scores

| Disability scores | COPD/emphysema | Chronic bronchitis | Asthma (n = 139) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 243) | Low severity†† (n = 123) | High severity (n = 119) | All (n = 209) | Low severity (n = 117) | High severity (n = 90) | ||

| AFFECTED* | |||||||

| Mean proportion of activities affected† | |||||||

| All activities | 45.9% | 30.0% | 62.3% | 28.4% | 15.1% | 45.7% | 27.3% |

| Obligatory | 41.3% | 24.9% | 58.3% | 27.1% | 13.3% | 45.0% | 21.9% |

| Committed | 50.4% | 33.0% | 68.3% | 30.6% | 17.2% | 47.9% | 28.9% |

| Discretionary | 44.9% | 30.3% | 59.5% | 27.3% | 14.4% | 44.1% | 28.9% |

| DIFFICULTY§ | |||||||

| All activities | 0.75 (0.67) | 0.43 | 1.08 | 0.40 (0.52) | 0.18 | 0.69 | 0.39 (0.55) |

| Obligatory | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.28 |

| Committed | 0.85 | 0.48 | 1.22 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.75 | 0.43 |

| Discretionary | 0.78 | 0.46 | 1.11 | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.43 |

| UNABLE** | |||||||

| Mean proportion of activities unable to perform | |||||||

| All activities | 7.8% | 3.8% | 11.9% | 3.0% | 0.7% | 6.0% | 2.4% |

| Obligatory | 1.4% | 1.0% | 1.8% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 1.1% | 0.6% |

| Committed | 8.7% | 4.5% | 13.1% | 3.8% | 1.1% | 7.3% | 2.8% |

| Discretionary | 10.3% | 4.7% | 16.1% | 3.6% | 0.5% | 7.5% | 3.1% |

Affected = any amount of difficulty or unable to perform

Proportion = (number of activities affected/number of activities rated)

Mean (standard deviation) difficulty rating

Unable is a subset of Affected.

Severity groups are defined using the median from the COPD Severity Score.24

Note: All means between groups are significantly different (p<.0001) by analysis of variance (between respiratory group) or t-test (between severity groups within respiratory groups), except for Unable, Obligatory. In each case, using post-hoc means comparisons for the ANOVAs, the COPD group was significantly different from the other two groups.

Difficulty level

Mean VLA difficulty followed the same pattern as the “affected” scores. Individuals with COPD had significantly higher difficulty scores than individuals with chronic bronchitis and asthma, whose scores were similar. Likewise, individuals in the high severity COPD and chronic bronchitis groups had significantly higher difficulty scores than individuals in the low severity groups.

Unable to perform

Individuals with COPD were more likely to be completely unable to perform activities than individuals in the other groups. Forty-two percent of the COPD group was unable to perform at least one VLA, compared to 17% of chronic bronchitis and 15% of asthma (p<.0001). Inability to perform activities was particularly notable in the COPD group for committed and discretionary activities (32% and 36%, respectively; Figure 2).

With the exception of obligatory activities, individuals with COPD were unable to perform significantly (p<.0001) more VLAs than individuals in the other two groups (Table 4). Within the COPD and chronic bronchitis groups, individuals with high severity were unable to perform significantly more VLAs than individuals with low severity.

Type of activity

In all cases, the least disability was noted in obligatory activities. Using the scores reflecting inability to perform activities, there was a clear gradient of disability, with the least disability seen in obligatory activities and the most in discretionary activities. This was particularly striking when considering the proportion who were unable to perform at least one VLA (Figure 2). For example, among the COPD group, 6%, 32%, and 36% were unable to perform at least one obligatory, committed, and discretionary activity, respectively. Similarly, in the chronic bronchitis group, 3%, 11% and 16% were unable to perform at least one obligatory, committed, and discretionary activity, respectively. In contrast using the proportion affected and mean difficulty, the greatest disability scores were noted in committed activities (Table 4).

Predictors of VLA disability

Results of multiple regression analyses to identify independent predictors of VLA disability are shown in Table 5. Sociodemographic variables as a group explained only 5% of the variance in the proportion of VLAs affected. Adding health status measures significantly increased the model R2 from 0.06 to 0.55. Greater fatigue and symptom ratings were strongly associated with greater VLA impact. Adding functional limitations produced a further significant increase in the model R2, from 0.55 to 0.66. In the final model, condition variables were added, using COPD as the reference group, but their addition did not change the model R2. Results of other regression models revealed similar findings for each of the three VLA subscales.

Table 5.

Predictors of Proportion of VLAs Affected

| Total | Obligatory | Committed | Discretionary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age 55–60 years | −5.1 a | −6.9 b | −6.5 b | −3.6 |

| Age 61−65 years | ||||

| Age 66+ years (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female | −2.8 | 2.9 | −3.2 | |

| White, non-Hispanic | −4.7 a | −6.3 a | −6.1 a | |

| Education < HS | ||||

| Unmarried/no partner | ||||

| Model R2 | .05 | .06 | .07 | .04 |

| Health status | ||||

| Ever smoker | ||||

| Obese | ||||

| Comorbid conditions: | ||||

| 1 | −3.8 a | −4.2 a | −3.8 | |

| 2 | ||||

| Fatigue rating | 2.7 d | 2.0 c | 2.8 d | 2.9 d |

| Symptom days | 1.1 d | 1.0 d | 1.3 d | 1.0 d |

| Symptoms nights | 0.7 c | 1.1 d | 0.9 c | |

| Model R2 | .55 | .51 | .51 | .49 |

| Functional limitations | ||||

| Functional limitations score | 21.3 d | 23.9 d | 23.3 d | 18.4 d |

| Model R2 | .66 | .64 | .61 | .57 |

| Condition | ||||

| COPD (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Chronic bronchitis | −3.0 | −3.8 | −4.4 | |

| Asthma | ||||

| Model R2 | .66 | .64 | .62 | .57 |

Note: Only predictors significant at p<.20 shown. Regression parameters from final model are shown. Letters indicate significance level of variable in multiple regression models:

= p<.05.

=p<.01.

=p<.001.

=p<.0001

DISCUSSION

VLA disability is common among individuals with respiratory conditions, particularly those with COPD, which we considered a priori to be more severe – an assumption borne out by comparisons of symptoms and functional limitations among the groups. Almost all reported at least one VLA affected (performed with difficulty or unable to perform) by COPD, and about half of this sample with COPD was unable to perform at least one VLA. The impact among individuals with chronic bronchitis and asthma was less marked, but still notable, with 74–84% reporting at least one activity affected, and about 15% unable to perform at least one activity.

In general, obligatory VLAs were least affected. A focus on obligatory activities, as is common in disability studies, would therefore miss a great deal of disability. When examining the proportion of activities affected, committed and discretionary activities evidenced more disability, but there was no clear pattern of which showed the greater impact. For inability to perform activities, however, there was a clear pattern. Likelihood of being unable to perform at least one VLA increased from a very small percentage for obligatory activities to about 10-fold for committed activities, and even more for discretionary activities, suggesting that discretionary, and then committed, activities, are the activities most commonly given up. This pattern is similar to that seen in other conditions.23, 25 Whether this is a voluntary relinquishment, to allow time and/or energy for other activities, or whether these activities are lost because of functional limitations and the increased physical demands of these activities requires further examination. Higher difficulty ratings seen for committed activities may be an indication that these activities, necessary for meeting life roles, require more effort and thus leave less time and effort for more discretionary activities. This hypothesis is consistent with previous reports that when dealing with disability, people may give up some activities in order to have time and energy for others.20,22, 26

Fatigue, symptom measures, and functional limitations were the strongest predictors of VLA disability. These measures were also significantly different across condition groups, with severity of VLA disability mirroring severity of symptoms across condition groups. After taking fatigue, symptom measures, and functional limitations into account, there were no significant differences in VLA disability among condition groups, suggesting that differences among these groups could be attributed largely to differences in symptoms and limitations. The role of severity was also clear when looking at differences in disability between individuals with high and low severity within the COPD and chronic bronchitis groups. In these analyses, individuals in the chronic bronchitis group with low severity reported the least disability, followed by individuals in the COPD group with low severity. The greatest disability was seen among individuals in the COPD group with high severity.

When considered from the disablement model perspective, many scales commonly used in COPD consist only of items assessing functional limitations (e.g., walking speed, ability to climb stairs) or obligatory activities (e.g., self-care). Few scales include items assessing the full spectrum of activities, and no scales focus clearly on disability rather than a mix of functional limitations and disability. Other scales have been developed that attempt to assess the broad range of activities affected by COPD. Leidy’s Functional Performance Inventory (FPI) covers six domains (body care, household maintenance, physical exercise, recreation, spiritual activities, and social activities)1, but has 65 items – more than twice as many items as the VLA scale, increasing the time needed for administration and scoring. Lareau’s 164-item Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspea Questionnaire (PFSDQ) assesses levels of dyspnea intensity with activities and changes that have occurred as a result of COPD in 79 activities.4 A modified PFSDQ has only 40 items and queries fatigue and dyspnea with ten activities, but all ten activities are related to self-care, walking, and climbing stairs.27 In addition to advantages due to length and focus compared with these other scales, the VLA disability scale has been used in a variety of chronic illnesses and, in the current study, a range of respiratory conditions, making it useful in studies of different illness groups.

Why is it important to consider disability in valued life activities? Performance of VLAs has been linked to psychological well-being more strongly than limitations in general functioning.9–11 Persons with rheumatoid arthritis who report high levels of depressive symptoms performed fewer VLAs than those who did not report depressive symptoms,28 and performance of VLAs was more closely related to quality of life among individuals with asthma than functional limitations.13 In COPD, VLA difficulty was predictive of psychological distress, whereas general physical functioning was not.15 In addition, loss of VLAs has been shown to be a stronger predictor of subsequent onset of new depressive symptoms than decline in general function.9, 10 Disability in certain types of activities, specifically recreational and social activities, appears to be especially linked to the onset of depressive symptoms.10 Performance of VLAs also appears to be more closely linked to individuals’ satisfaction with their abilities than other type of functioning.12 Given that many individuals are referred to pulmonary rehabilitation because they are dissatisfied with their ability to perform daily activities16, a measure that focuses on a wide range of daily life activities may be the most appropriate way to assess the outcomes of rehabilitation. Another consideration is that as more effective treatments become available, patient goals will likely expand beyond simple preservation of ADLs. Measurement of a wider range of life activities coincides with these new expectations.

There are potential limitations to this study. Our assessment of VLAs may have been incomplete. While the addition of activities may produce a more sensitive instrument, there is no reason to believe that the overall tenor of these results would change as a result. Factors other than those included here may affect VLA disability. For example, cognitive function may be an important determinant of VLA disability. Unfortunately, an adequate measure of cognitive function was not available for this cohort, although such data are currently being collected on a portion of this sample, enabling examination of this association at a later time. The airways cohort may be unrepresentative of individuals with these conditions. However, because participants were recruited from the community rather than through an academic medical center or tertiary care center, it is probable that the distribution of disease severity and other relevant characteristics is more similar to the population of individuals with these conditions. Because we did not have results of pulmonary function testing or medical records and we relied on self-reports of physicians’ diagnoses, some individuals may have been classified into the wrong disease group. It is likely, though, that such misclassification would tend to attenuate differences among the groups, biasing our results toward null findings.

In summary, disability in valued life activities is very common among individuals with COPD and other airways conditions, and more common in committed and discretionary activities than in obligatory activities. A focus on obligatory activities, as is common in disability measures, would therefore miss a great deal of the impact of these conditions. VLA disability appears to play a substantial role in individuals’ psychological status and satisfaction with functioning.9, 10, 12, 14, 16 Future research should identify factors associated with the development and progression of VLA disability, as well as factors that may protect against or ameliorate such disability. The latter is especially important, since these may represent potential targets for intervention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant number R01 HL067438 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

References

- 1.Leidy N, Knebel A. Clinical validation of the functional performance inventory in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care. 1999;44:932–939. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leidy N. Psychometric properties of the Functional Performance Inventory in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nurs Res. 1999;48:20–28. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones P, Quirk F, Baveystock C. The St George’s respiratory questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lareau S, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Janson-Bjerklie S, Roos P. Development and testing of the pulmonary functional status and dyspnea questionnaire (PFSDQ) Heart Lung. 1994;23:242–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yohannes A, Roomi J, Winn S, Hons B, Connolly M. The Manchester Respiratory Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to pulmonary rehabilitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1496–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leidy N, Haase J. Functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative analysis. Adv Nurs Sci. 1996;18:77–89. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leidy N. Subjective measurement of activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2007;4:243–249. doi: 10.1080/15412550701480414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicutto L, Brooks D, Henderson K. Self-care issues from the perspective of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz P, Yelin E. The development of depressive symptoms among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:49–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz P, Yelin E. Activity loss and the onset of depressive symptoms: Do some activities matter more than others? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1194–1202. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1194::AID-ANR203>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz P. Function, disability, and psychological well-being. Adv Psychosom Med. 2004;25:41–62. doi: 10.1159/000079057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz P, Yelin E, Lubeck D, Buatti M, Wanke L. Satisfaction with function: What type of function do rheumatoid arthritis patients value most? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:S185. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz P, Yelin E, Eisner M, Earnest G, Blanc P. Performance of valued life activities reflected asthma-specfiic quality of life more than general physical function. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz P, Yelin E, Eisner M, Chen H, Blanc P. Prevalence and psychological impact of disability in valued life activities in COPD and related airways conditions. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:A519. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz P, Eisner M, Yelin E, et al. Functioning and psychological status among individuals with COPD. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1835–1843. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-5693-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, et al. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1390–1413. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1211ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verbrugge L. Disability. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16:741–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verbrugge L, Jette A. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbrugge L, Gruber-Baldini A, Fozard J. Age differences and age changes in activities: Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 1996;51B:S30–S41. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.1.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badley E, Rothman L, Wang P. Modeling physical dependence in arthritis: the relative contribution of specific disabilities and environmental factors. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:335–345. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanc P, Eisner M, Trupin L, Yelin E, Katz P, Balmes J. The association between occupational factors and adverse health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:661–667. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.010058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yelin E, Lubeck D, Holman H, Epstein W. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: The activities of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis compared to controls. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz P, Morris A, Yelin E. Prevalence and predictors of disability in valued life activities among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:763–769. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisner M, Trupin L, Katz P, et al. Development and validation of a survey-based COPD severity score. Chest. 2005;127:1890–1897. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz P, Morris A, Trupin L, Yazdany J, Julian L, Yelin E. Disability in valued life activities among individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum (Arthritis Care Res) 2008;59:465–473. doi: 10.1002/art.23536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gignac M, Cott C, Badley E. Adaptation to chronic illness and disability and its relationship to perceptions of independence and dependence. J Gerontol: Psychol Sci. 2000;55B:362–372. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.p362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lareau S, Meek P, Roos P. Development and testing of the modified version of the pulmonary functional status and dyspnea questionnaire (PFSDQ-M) Heart Lung. 1998;27:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(98)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz P, Yelin E. Life activities of persons with rheumatoid arthritis with and without depressive symptoms. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7:69–77. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health and Retirement Survey. website:. http://www.umich.edu/~hrswww/docs/qnaires/online.html.