Abstract

The Mycosphaerella complex is both poly- and paraphyletic, containing several different families and genera. The genus Mycosphaerella is restricted to species with Ramularia anamorphs, while Septoria is restricted to taxa that cluster with the type species of Septoria, S. cytisi, being closely related to Cercospora in the Mycosphaerellaceae. Species that occur on graminicolous hosts represent an as yet undescribed genus, for which the name Zymoseptoria is proposed. Based on the 28S nrDNA phylogeny derived in this study, Zymoseptoria is shown to cluster apart from Septoria. Morphologically species of Zymoseptoria can also be distinguished by their yeast-like growth in culture, and the formation of different conidial types that are absent in Septoria s.str. Other than the well-known pathogens such as Z. tritici, the causal agent of septoria tritici blotch on wheat, and Z. passerinii, the causal agent of septoria speckled leaf blotch of barley, both for which epitypes are designated, two leaf blotch pathogens are also described on graminicolous hosts from Iran. Zymoseptoria brevis sp. nov. is described from Phalaris minor, and Z. halophila comb. nov. from leaves of Hordeum glaucum. Further collections are now required to elucidate the relative importance, host range and distribution of these species.

Keywords: Hordeum vulgare, ITS, LSU, multilocus sequence typing, Mycosphaerella, Septoria, systematics, Triticum aestivum

INTRODUCTION

More than 10 000 names have been described in the genus Mycosphaerella (Capnodiales, Dothideomycetes) and its associated anamorph genera (Cercospora, Pseudocercospora, Septoria, Ramularia, etc.) (Crous et al. 2009a), making it one of the largest genera of plant pathogenic Ascomycetes known to date (Crous 2009). However, in contrast to earlier phylogenetic studies based on the ITS region (Stewart et al. 1999, Crous et al. 1999, 2000, 2001, Goodwin et al. 2001), more robust multi-gene phylogenies have revealed Mycosphaerella to be polyphyletic (Crous et al. 2007, 2009b, Schoch et al. 2009a, b), suggesting that Mycosphaerella s.l. should be subdivided to reflect natural groups (genera) as defined by their anamorphs.

The genus Mycosphaerella is typified by M. punctiformis, which has a Ramularia anamorph, R. endophylla (Verkley et al. 2004a). Ever since it was established, the name Mycosphaerella has been used to describe related and unrelated, small loculoascomycetes (in some cases even asexual coelomycetes) (Aptroot 2006), prompting Crous et al. (2009b), to suggest that the older generic name Ramularia (1833), rather than the confused name Mycosphaerella (1884) should be used for this well-defined morphologic (Braun 1998) and phylogenetic clade of fungi (Crous et al. 2009b, Kirschner 2009).

The genus Septoria Sacc. (1884) currently contains almost 3 000 species (Verkley & Priest 2000, Verkley et al. 2004b), several of which have Mycosphaerella-like teleomorphs. The type species is Septoria cytisi (Fig. 1), a pathogen of Cytisus laburnum (= Laburnum anagyroides). Septoria represents a polyphyletic assembly of anamorph genera that cluster mostly in the Mycosphaerellaceae (a family incorporating many plant pathogenic coelomycetes), although Septoria-like anamorphs have also evolved outside this family (Crous et al. 2009b). In this regard some Septoria species on graminicolous hosts (e.g. S. passerinii and S. tritici) have a distinct dimorphic lifestyle. Besides their mycelial state, they can exhibit a yeast-like growth in culture via microcyclic conidiation, distinguishing them from Septoria s.str. Furthermore, phylogenetically the Septoria-like species occurring on graminicolous hosts have also been found to cluster apart from Septoria species occurring on other hosts (Crous et al. 2001, Verkley et al. 2004b). This clear phylogenetic separation, together with the unique yeast-like growth for S. tritici and S. passerinii, led to the hypothesis that the S. tritici clade did not belong to Septoria s.str., but should be classified as a separate genus. In order to prove this hypothesis, the phylogenetic relationship of the type species of the genus Septoria (S. cytisi) needs to be determined. However these data are not currently available, as other than herbarium material, we have not been able to recollect or locate any living strains of S. cytisi.

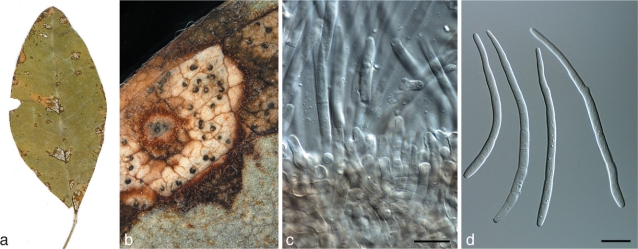

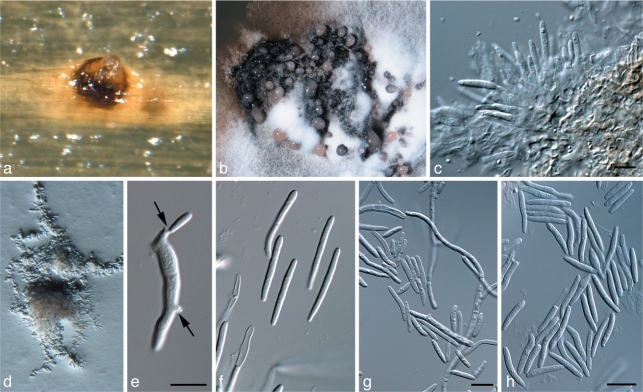

Fig. 1.

Septoria cytisi (BPI 378994). a. Leaf with leaf spots; b. lesion with pycnidia oozing conidial cirrhi; c. conidiogenous cells showing sympodial and percurrent proliferation; d. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

The aims of this study were thus to isolate and sequence part of the nuclear ribosomal DNA operon from S. cytisi herbarium material, and to test the hypothesis whether the S. tritici clade can represent a new genus of fungi. A further aim was to resolve the identity of Septoria-like species occurring on graminicolous hosts. To this end partial gene sequences of five loci viz. actin (ACT), calmodulin (CAL), β-tubulin (TUB), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) and 28S nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (LSU) were generated and analysed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates

Symptomatic leaves were collected from several localities (Table 1), and leaves with visible asexual fruiting bodies were immediately subjected to direct fungal isolation, or alternatively were first incubated in moist chambers to stimulate sporulation. Single-conidial isolates were established on malt extract agar (MEA; 20 g/L Biolab malt extract, 15 g/L Biolab agar) using the previously described procedure (Crous et al. 2009c). Cultures were later plated on fresh MEA, 2 % tap water agar supplemented with green, sterile barley leaves (WAB), 2 % potato-dextrose agar (PDA), and oatmeal agar (OA) (Crous et al. 2009c), and subsequently incubated at 25 °C under near-ultraviolet light to promote sporulation. Reference strains are maintained in the culture collection of the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands, the Plant Research Institute, Wageningen, the Netherlands, and the Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection, Tehran, Iran (Table 1), and supplemented with other relevant isolates present in the CBS collection. Descriptions, nomenclature, and illustrations were deposited in MycoBank (www.mycobank.org, Crous et al. 2004).

Table 1.

Details of cultures subjected to DNA sequencing.

| Species | Isolate no 1 | Host | Location | Collected by | GenBank Accession no

2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | CAL | ITS | TUB | RPB2 | LSU | |||||

| Cercospora apii | CBS 118712 | – | Fiji | P. Tyler | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852583 |

| C. ariminensis | CBS 137.56 | Hedysarum coronarium | Italy | M. Ribaldi | – | – | – | – | – | JF700933 |

| C. beticola | CBS 124.31 | Beta vulgaris | Romania | – | – | – | – | – | – | JF700934 |

| Cladosporium bruhnei | CBS 188.54 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | JF700935 |

| CBS 115683 | Douglas-fir pole | USA | – | – | – | – | – | – | JF700936 | |

| Dissoconium australiensis | CBS 120729 | Eucalyptus platyphylla | Australia | P.W. Crous | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852588 |

| D. commune | CPC 12397 | Eucalyptus globulus | Australia | I.W. Smith | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852591 |

| D. dekkeri | CPC 13479 | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Thailand | W. Himaman | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852595 |

| Dothistroma pini | CBS 116484 | Pinus nigra | USA | G. Adams | – | – | – | – | – | JF700937 |

| D. septosporum | CPC 16799 | Pinus mugo uncinata | The Netherlands | W. Quaedvlieg | – | – | – | – | – | JF700938 |

| CPC 3779 (= 112498) | Pinus radiata | Ecuador | – | – | – | – | – | – | JF700939 | |

| Lecanosticta acicola | CBS 871.95 | Pinus radiata | France | M. Morelet | – | – | – | – | – | GU214663 |

| CPC 17940 | Pinus sp. | Mexico | M. de Jesus Yanez Morales | – | – | – | – | – | JF700940 | |

| IMI 281598 | Pinus oocarpa | Guatemala | H.C. Evans | – | – | – | – | – | JF700941 | |

| Mycosphaerella ellipsoidea | CBS 111167 | Eucalyptus cladocalyx | South Africa | A.R. Wood | – | – | – | – | – | GU214450 |

| M. elongata | CBS 120735 | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Venezuela | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | JF700942 |

| M. marksii | CBS 110981 | Eucalyptus sp. | Tanzania | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | JF700943 |

| Mycosphaerella sp. | CBS 110843 | Eucalyptus cladocalyx | South Africa | P.W. Crous | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852602 |

| M. vietnamensis | CBS 119974 | Eucalyptus grandis | Vietnam | T.I. Burgess | – | – | – | – | – | JF700944 |

| Passalora eucalypti | CBS 111318 | Eucalyptus saligna | Brazil | P.W. Crous | – | – | – | – | – | GU214458 |

| Phaeophleospora eugeniae | CPC 15143 | Eugenia uniflora | Brazil | A.C. Alfenas | – | – | – | – | – | FJ493206 |

| P. eugeniicola | CPC 2557 | Eugenia sp. | Brazil | A.C. Alfenas | – | – | – | – | – | JF700945 |

| Pseudocercospora gracilis | CPC 11144 | Eucalyptus sp. | Indonesia | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | JF700946 |

| P. heimii | CPC 11716 | – | Brazil | A.C. Alfenas | – | – | – | – | – | JF700947 |

| P. heimioides | CBS 111190 | Eucalyptus sp. | Indonesia | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | GU214439 |

| P. irregulariramosa | CBS 111211 | Eucalyptus saligna | South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852609 |

| P. pseudoeucalyptorum | CPC 13769 | Eucalyptus punctata | South Africa | P.W. Crous | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852642 |

| P. robusta | CBS 111175 | Eucalyptus robur | Malaysia | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | JF700948 |

| P. stromatosa | CBS 101953 | Protea sp. | South Africa | S. Denman | – | – | – | – | – | EU167598 |

| Ramularia endophylla | CBS 113265 | Quercus robur | The Netherlands | G. Verkley | – | – | – | – | – | DQ470968 |

| R. eucalypti | CBS 120726 | Corymbia grandifolia | Italy | W. Gams | – | – | – | – | – | JF700949 |

| R. lamii | CPC 11312 | Leonurus sibiricus | Korea | H.D. Shin | – | – | – | – | – | JF700950 |

| Ramulispora sorghi | CBS 110578 | Sorghum sp. | South Africa | D. Nowell | – | – | – | – | – | JF700951 |

| CBS 110579 | Sorghum sp. | South Africa | D. Nowell | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852654 | |

| Septoria azaleae | CBS 352.49 | Rhododendron sp. | Belgium | J. van Holder | – | – | – | – | – | JF700952 |

| S. betulae | CBS 116724 | Betula pubescens | Scotland | S. Green | – | – | – | – | – | JF700953 |

| S. cytisi | USO 378994 (Herbarium specimen) | Laburnum anagyroides | ‘Czechoslovakia’ | J. A. Baumler | – | – | JF700932 | – | – | JF700954 |

| S. gerberae | CBS 410.61 | Gerbera jamesonii | Italy | W. Gerlach | – | – | – | – | – | JF700955 |

| S. menthae | CBS 404.34 | – | Japan | T. Hemmi | – | – | – | – | – | JF700956 |

| S. rosae | CBS 355.58 | Rosa sp. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | JF700957 |

| S. rubi | CBS 102327 | Rubus sp. | The Netherlands | G. Verkley | – | – | – | – | – | JF700958 |

| S. verbenae | CBS 113481 | Septoria sp. | New Zealand | G. Verkley | – | – | – | – | – | JF700959 |

| Teratosphaeria fibrillosa | CBS 121707 | Protea sp. | South Africa | P.W. Crous & L. Mostert | – | – | – | – | – | GU323213 |

| T. molleriana | CBS 117926 | Eucalyptus globulus | Australia | – | – | – | – | – | – | JF700960 |

| T. nubilosa | CPC 12830 | Eucalyptus globulus | Portugal | A. Philips | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852697 |

| T. pseudocryptica | CPC 11264 | Eucalyptus sp. | New Zealand | J. Stalpers | – | – | – | – | – | JF700961 |

| T. secundaria | CBS 115608 | Eucalyptus grandis | Brazil | A.C. Alfenas | – | – | – | – | – | JF700962 |

| T. suberosa | CPC 13090 | Eucalyptus agglomerata | Australia | A.J. Cargenie | – | – | – | – | – | JF700963 |

| Verrucisporota daviesiae | CBS 116002 | Daviesia latifolia | Australia | V. beilhartz | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852730 |

| V. proteacearum | CBS 116003 | Grevillea sp. | Australia | J.L. Alcorn | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852731 |

| Zasmidium anthuriicola | CBS 118742 | Anthurium sp. | Thailand | C.F. Hill | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852732 |

| Z. citri-grisea | CPC 13467 | Eucalyptus sp. | Thailand | W. Himaman | – | – | – | – | – | GQ852733 |

| Z. nabiacense | CBS 125010 | Eucalyptus sp. | Australia | A.J. Cargenie | – | – | – | – | – | JF700964 |

| Z. pseudoparkii | CBS 110999 | Eucalyptus grandis | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | JF700965 |

| Z. xenoparkii | CBS 111185 | Eucalyptus sp. | Indonesia | M.J. Wingfield | – | – | – | – | – | JF700966 |

| Zymoseptoria brevis | IRAN1485C (= CPC 18102) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701035 | JF701103 | JF700866 | JF700967 | JF700798 | – |

| CPC 18106 (= 8S) = CBS 128853 | Phalaris minor | Iran | – | JF701036 | JF701104 | JF700867 | JF700968 | JF700799 | – | |

| IRAN1486C (= CPC 18107) | Phalaris minor | Iran | – | JF701037 | JF701105 | JF700868 | JF700969 | JF700800 | – | |

| CPC 18109 (= 81) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701038 | JF701106 | JF700869 | JF700970 | JF700801 | – | |

| CPC 18110 (= 83) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701039 | JF701107 | JF700870 | JF700971 | JF700802 | – | |

| CPC 18111 (= 84) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701040 | JF701108 | JF700871 | JF700972 | JF700803 | – | |

| CPC 18112 (= 85) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701041 | JF701109 | JF700872 | JF700973 | JF700804 | – | |

| CPC 18113 (= 86) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701042 | JF701110 | JF700873 | JF700974 | JF700805 | – | |

| CPC 18114 (= 87) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701043 | JF701111 | JF700874 | JF700975 | JF700806 | – | |

| CPC 18115 (= 88) | Phalaris paradoxa | Iran | – | JF701044 | JF701112 | JF700875 | JF700976 | JF700807 | – | |

| Zymoseptoria halophila | IRAN1483C (= CPC 18105) = CBS 128854 | Hordeum glaucum | Iran | – | JF701045 | JF701113 | JF700876 | JF700977 | JF700808 | – |

| CBS 120382 | Hordeum vulgare | USA | S. Goodwin | JF701046 | JF701114 | JF700877 | JF700978 | JF700809 | – | |

| Z. passerinii | CBS 120384 | Hordeum vulgare | P71 × P83A, USA | S. Ware | JF701047 | JF701115 | JF700878 | JF700979 | JF700810 | – |

| CBS 120385 | Hordeum vulgare | P71 × P83B, USA | S. Ware | JF701048 | JF701116 | JF700879 | JF700980 | JF700811 | – | |

| IRAN1489C (= CPC 18099) | Aegilops tauschii | Iran | – | JF701049 | JF701117 | JF700880 | JF700981 | JF700812 | – | |

| CPC 18100 | Aegilops tauschii | Iran | – | JF701050 | JF701118 | JF700881 | JF700982 | JF700813 | – | |

| CPC 18101 | Aegilops tauschii | Iran | – | JF701051 | JF701119 | JF700882 | JF700983 | JF700814 | – | |

| IRAN1484C (= CPC 18103) | Calamagrostis sp. | Iran | – | JF701052 | JF701120 | JF700883 | JF700984 | JF700815 | – | |

| CPC 18116 | Avena sp. | Iran | – | JF701053 | JF701121 | JF700884 | JF700985 | JF700816 | – | |

| CPC 18117 | Avena sp. | Iran | – | JF701054 | JF701122 | JF700885 | JF700986 | JF700817 | – | |

| Z. tritici | CBS 392.59 | Triticum aestivum | – | E. Becker | JF701055 | JF701123 | AY152603 | JF700987 | JF700818 | – |

| CBS 398.52 | Triticum aestivum | Switzerland | E. Muller | JF701056 | JF701124 | JF700886 | JF700988 | JF700819 | – | |

| IPO 01001 | Triticum aestivum | New Zeeland | – | JF701057 | JF701125 | JF700887 | JF700989 | JF700820 | – | |

| IPO 02158 | Triticum aestivum | Iran | – | JF701058 | JF701126 | JF700888 | JF700990 | JF700821 | – | |

| IPO 03008 | Triticum aestivum | Germany | – | JF701059 | JF701127 | JF700889 | JF700991 | JF700822 | – | |

| IPO 320 | Triticum aestivum | Romania | – | JF701060 | JF701128 | JF700890 | JF700992 | JF700823 | – | |

| IPO 323 | Triticum aestivum | The Netherlands | – | JF701061 | JF701129 | AF181692 | JF700993 | JF700824 | – | |

| IPO 86013 | Triticum aestivum | Turkey | – | JF701062 | JF701130 | JF700891 | JF700994 | JF700825 | – | |

| IPO 86015 | Triticum aestivum | Morocco | – | JF701063 | JF701131 | JF700892 | JF700995 | JF700826 | – | |

| IPO 86036 | Triticum aestivum | Israel | – | JF701064 | JF701132 | JF700893 | JF700996 | JF700827 | – | |

| IPO 87016 | Triticum aestivum | Uruguay | – | JF701065 | JF701133 | JF700894 | JF700997 | JF700828 | – | |

| IPO 88004 | Triticum aestivum | Ethiopia | – | JF701066 | JF701134 | JF700895 | JF700998 | JF700829 | – | |

| IPO 90012 | Triticum aestivum | Mexico | – | JF701067 | JF701135 | JF700896 | JF700999 | JF700830 | – | |

| IPO 90015 | Triticum aestivum | Peru | – | JF701068 | JF701136 | JF700897 | JF701000 | JF700831 | – | |

| IPO 91009 | Triticum durum | Tunisia | – | JF701069 | JF701137 | JF700898 | JF701001 | JF700832 | – | |

| IPO 91010 | Triticum aestivum | Tunisia | – | JF701070 | JF701138 | JF700899 | JF701002 | JF700833 | – | |

| IPO 91012 | Triticum durum | Tunisia | – | JF701071 | JF701139 | JF700900 | JF701003 | JF700834 | – | |

| IPO 91014 | Triticum durum | Tunisia | – | JF701072 | JF701140 | JF700901 | JF701004 | JF700835 | – | |

| IPO 91016 | Triticum durum | Tunisia | – | JF701073 | JF701141 | JF700902 | JF701005 | JF700836 | – | |

| IPO 91020 | Triticum durum | Morocco | – | JF701074 | JF701142 | JF700903 | JF701006 | JF700837 | – | |

| IPO 92002 | Triticum aestivum | Portugal | – | JF701075 | JF701143 | JF700904 | JF701007 | JF700838 | – | |

| IPO 92003 | Triticum aestivum | Portugal | – | JF701076 | JF701144 | JF700905 | JF701008 | JF700839 | – | |

| IPO 92005 | Triticale sp. | Portugal | – | JF701077 | JF701145 | JF700906 | JF701009 | JF700840 | – | |

| IPO 92032 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701078 | JF701146 | JF700907 | JF701010 | JF700841 | – | |

| IPO 92050 | Triticum aestivum | Kenya | – | JF701079 | JF701147 | JF700908 | JF701011 | JF700842 | – | |

| IPO 94231 | Triticum aestivum | USA | – | JF701080 | JF701148 | JF700909 | JF701012 | JF700843 | – | |

| IPO 94236 | Triticum aestivum | USA | – | JF701081 | JF701149 | JF700910 | JF701013 | JF700844 | – | |

| IPO 95001 | Triticum aestivum | Switzerland | – | JF701082 | JF701150 | JF700911 | JF701014 | JF700845 | – | |

| IPO 95006 | Triticum durum | Syria | – | JF701083 | JF701151 | JF700912 | JF701015 | JF700846 | – | |

| IPO 95013 | Triticum aestivum | Syria | – | JF701084 | JF701152 | JF700913 | JF701016 | JF700847 | – | |

| IPO 95025 | Triticum durum | Syria | – | JF701085 | JF701153 | JF700914 | JF701017 | JF700848 | – | |

| IPO 95026 | Triticum durum | Syria | – | JF701086 | JF701154 | JF700915 | JF701018 | JF700849 | – | |

| IPO 95027 | Triticum durum | Syria | – | JF701087 | JF701155 | JF700916 | JF701019 | JF700850 | – | |

| IPO 95028 | Triticum aestivum | Syria | – | JF701088 | JF701156 | JF700917 | JF701020 | JF700851 | – | |

| IPO 95031 | Triticum durum | Syria | – | JF701089 | JF701157 | JF700918 | JF701021 | JF700852 | – | |

| IPO 95046 | Triticum durum | Syria | – | JF701090 | JF701158 | JF700919 | JF701022 | JF700853 | – | |

| IPO 95047 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701091 | JF701159 | JF700920 | JF701023 | JF700854 | – | |

| IPO 95050 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701092 | JF701160 | JF700921 | JF701024 | JF700855 | – | |

| IPO 95052 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701093 | JF701161 | JF700922 | JF701025 | JF700856 | – | |

| IPO 95054 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701094 | JF701162 | JF700923 | JF701026 | JF700857 | – | |

| IPO 95062 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701095 | JF701163 | JF700924 | JF701027 | JF700858 | – | |

| IPO 95071 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701096 | JF701164 | JF700925 | JF701028 | JF700859 | – | |

| IPO 95072 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701097 | JF701165 | JF700926 | JF701029 | JF700860 | – | |

| IPO 95073 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701098 | JF701166 | JF700927 | JF701030 | JF700861 | – | |

| IPO 95074 | Triticum aestivum | Algeria | – | JF701099 | JF701167 | JF700928 | JF701031 | JF700862 | – | |

| IPO 97016 | Triticum aestivum | Italy | – | JF701100 | JF701168 | JF700929 | JF701032 | JF700863 | – | |

| IPO 98115 | Triticum aestivum | Hungary | – | JF701101 | JF701169 | JF700930 | JF701033 | JF700864 | – | |

| IPO 99048 | Triticum aestivum | France | – | JF701102 | JF701170 | JF700931 | JF701034 | JF700865 | – | |

1 CBS: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CPC: Pedro Crous working collection housed at CBS; IMI: International Mycological Institute; USO: United States Department of Agriculture, National Fungus Collections (BPI); IPO: Research Institute for Plant Protection, Wageningen (IRAN); Iranian Fungal Culture Collection, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection.

2 ACT = Actin, TUB = β-tubulin, CAL = Calmodulin, LSU = 28S large subunit of the nrRNA gene, RPB2= RNA polymerase II second largest subunit.

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

Herbarium specimens

Ten S. cytisi herbarium specimens occurring on Cytisus laburnum (= Laburnum anagyroides), were obtained from the U.S. National Fungus Collections (BPI) in Beltsville, Maryland, USA (Table 2). After microscopic inspection, the five specimens with the least amount of surface contamination (yeast and saprobes) where selected for DNA extraction (Table 2). Using a stereo microscope, ± 25 pycnidia, including their dried conidial cirrhi, where excised from each respective herbarium specimen, and suspended in tubes with 20 μL STL buffer from an E.Z.N.A. ® Forensic DNA Kit (Omegabiotek, Norcross). Special care was taken to keep the amount of contaminant leaf material, excised together with the fungal tissue, as low as possible. The fungal material was kept in STL buffer to rehydrate for 24 h at 4 °C, after which the fungal cell walls were degraded by two cycles of freezing with liquid nitrogen and immediate re-heating to 99 °C. The genomic DNA extraction was performed using the ‘Isolation of DNA from dried blood’ protocol available in the E.Z.N.A. ® Forensic DNA Kit with one modification: in order to increase the final DNA concentration, only 50 μL of preheated (70 °C) elution buffer was used to elude the DNA from the column.

Table 2.

Herbarium specimens of Laburnum anagyroides infected with Septoria cytisi, obtained from the U.S. National Fungus Collections (BPI), Maryland, USA. Specimens marked with an asterisk were selected for DNA extraction.

| BPI accession number | Host | Year collected | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0378986 | Laburnum anagyroides | 1913 | France |

| 0378987 | Laburnum anagyroides | 1933 | Romania |

| 0378988 | Laburnum anagyroides | 1893 | Italy |

| 0378989* | Laburnum anagyroides | 1929 | ‘Czechoslovakia’ |

| 0378990* | Laburnum anagyroides | 1874 | Italy |

| 0378991* | Laburnum anagyroides | 1885 | ‘Czechoslovakia’ |

| 0378992 | Laburnum anagyroides | 1903 | Italy |

| 0378993* | Laburnum anagyroides | 1929 | Austria |

| 0378994* | Laburnum anagyroides | 1884 | ‘Czechoslovakia’ |

| 0378995 | Laburnum anagyroides | 1876 | Italy |

Genus-specific primers had to be designed because the use of generic fungal ITS and LSU primers only generated sequences of contaminants (mostly yeasts). For the amplification reactions concerning the herbarium specimens, the Verbatim High Fidelity DNA Polymerase Kit (Thermo Scientific) was used in combination with the Septoria-specific S18S-2 forward primer (annealing to the nuclear rDNA operon at the 3′-end of the 18S nrRNA gene (SSU); Table 2), together with the Septoria-specific SITS2_Fd reverse primer (annealing to the nuclear rDNA operon at the 5′-end of the 28S nrRNA gene (LSU); Table 2), in order to amplify a region spanning the 5.8S nrRNA gene and the first and second internal transcribed spacer regions (Fig. 2). This amplification reaction was set up in a volume of 12.5 μL using 5× High Fidelity buffer (with MgCl2), 0.8 μM of each primer, 2 μL of gDNA, 150 μM dNTP mix and 0.1 unit of Verbatim polymerase using a MyCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). PCR amplification conditions were set as follows: an initial denaturation temperature at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation temperature at 98 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 52 °C for 30 s, primer extension at 72 °C for 30 s and final extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The resulting PCR products were then size-fractionated on a 3 % (w/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide, excised from the gel and subsequently sequenced as described by Cheewangkoon et al. (2008).

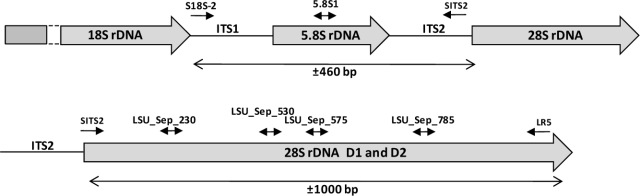

Fig. 2.

A diagrammatic representation of part of the nrDNA operon indicating the positions of the Septoria-specific primers used to generate ITS and LSU sequences of S. cytisi.

Degradation and shearing of the S. cytisi herbarium gDNA made it impossible to directly amplify and sequence the approximate 1 300 bp needed to cover both the ITS and D1–D3 domains of the 28S nrDNA in a single reaction. Therefore, specific primers were developed from the obtained S. cytisi ITS1 sequence, spaced about 300 bp apart (Table 2, Fig. 2), which made it possible to sequentially amplify and sequence the entire regions of both the ITS, and the D1–D3 domains of the LSU of S. cytisi sequentially, and later to sequence it as described by Cheewangkoon et al. (2008).

Fungal cultures

Genomic DNA was extracted from mycelium growing on MEA (Table 1), using the UltraClean® Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Solana Beach, CA, USA). These strains were screened for five loci, namely ITS, Actin (ACT), calmodulin (CAL), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) and β-tubulin (TUB) (Table 3). DNA amplification and sequencing reactions were performed as described by Cheewangkoon et al. (2008).

Table 3.

Primer combinations used during this study for generic amplification and sequencing.

| Locus | Primer | Primer sequence 5′ to 3′ | Orientation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | ACT-512F | ATGTGCAAGGCCGGTTTCGC | Forward | Carbone & Kohn (1999) |

| Actin | ACT2Rd | ARRTCRCGDCCRGCCATGTC | Reverse | Groenewald, unpubl. data |

| Calmodulin | CAL-228F | GAGTTCAAGGAGGCCTTCTCCC | Forward | Carbone & Kohn (1999) |

| Calmodulin | CAL2Rd | TGRTCNGCCTCDCGGATCATCTC | Reverse | Groenewald, unpubl. data |

| β-tubulin | TUB2Fd | GTBCACCTYCARACCGGYCARTG | Forward | Aveskamp et al. (2009) |

| β-tubulin | TUB4Rd | CCRGAYTGRCCRAARACRAAGTTGTC | Reverse | Aveskamp et al. (2009) |

| RPB2 | fRPB2-5F | GAYGAYMGWGATCAYTTYGG | Forward | Liu et al. (1999) |

| RPB2 | fRPB2-5F+414R | ACMANNCCCCARTGNGWRTTRTG | Reverse | Present study |

| LSU | LSU1Fd | GRATCAGGTAGGRATACCCG | Forward | Crous et al. (2009a) |

| LSU | LR5 | TCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG | Reverse | Vilgalys & Hester (1990) |

Phylogenetic analysis

To determine whether the multi-locus DNA sequence datasets were congruent, a partition homogeneity test (Farris et al. 1994) of all possible combinations was performed in PAUP v4.0b10 (Swofford 2003) with 1 000 replications. Parallel to this, a 70 % Neighbour-Joining (NJ) reciprocal bootstrap method with Maximum Likelihood distance (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996, Lombard et al. 2010) was also employed to check congruency. The models of evolution for the NJ tree were estimated with Modeltest v3.7 (Posada & Crandall 1998) and bootstrap analyses (10 000 replicates) were performed in PAUP. Resulting NJ tree topologies were visually compared for conflicts between the individual gene regions. Maximum-parsimony genealogies for individual datasets and the combined dataset were estimated in PAUP using heuristic searches based on 1 000 random taxon addition sequences and the best trees were saved. All characters were weighted equally and alignment gaps were treated as missing data. Branches of zero length were collapsed and all multiple, equally most parsimonious trees were saved. Tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and the rescaled consistency index (RC) were calculated in PAUP for the equally most parsimonious trees and the resulting trees were printed with TreeView (Page 1996) and the alignments and phylogenetic trees were lodged in TreeBASE (www.treebase.org). All novel sequences derived from this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 1). Trees were either rooted to Cladosporium bruhnei for the LSU tree, or to Mycosphaerella punctiformis for the multigene tree.

Morphology

Descriptions were based on fungal cultures sporulating in vitro on WAB, incubated under continuous near-ultraviolet light for 2–4 wk. Wherever possible, 30 measurements (×1 000 magnification) were made of structures mounted in lactic acid, with the extremes of spore measurements given in parentheses. Colony colours (surface and reverse) were assessed after 1 mo on MEA, PDA and OA at 25 °C in the dark, using the colour charts of Rayner (1970).

RESULTS

ITS and LSU amplification and sequencing of S. cytisi

The gDNA extractions from the S. cytisi herbarium samples were performed on the herbarium specimens indicated in Table 2, and both the ITS and a partial LSU regions where targeted for these isolates using Septoria-specific primers (Table 4). An ITS amplicon length of 486 bp was achieved from herbarium sample US0378993 while the other samples yielded only partial ITS amplicons varying in length from 440 bp in sample US0378994 to ± 200 bp in sample US0378990; amplicons of sample US0378991 only yielded contamination sequences with general primers and did not amplify with either Septoria- or S. cytisi-specific primers.

Table 4.

Septoria cytisi-specific ITS and LSU primers used for amplification and sequencing. Nucleotide positions were determined relative to the ITS/LSU sequence of Zymoseptoria tritici (GenBank accession FN428877).

| Primer name | Primer sequence 5′ to 3′ | Orientation | Relative position |

|---|---|---|---|

| S18S-2 | CGTAGGTGAACYTGCGRAGGGATCATTACYGAGTGA | Forward | 7 |

| 5.8S1Fd | CTCTTGGTTCBVGCATCG | Forward | 240 |

| SITS2_Fwd | CCGCCCGCACTCCGAAGCGATTAATGAAATC | Forward | 459 |

| SITS2_Rev | GATTTCATTAATCGCTTCGGAGTGCGGGCGG | Reverse | 459 |

| LSU_Sep_230_Fwd | TATGTGACCGGCCCGCACCCTTTAC | Forward | 710 |

| LSU_Sep_230_Rev | GTAAAGGGTGCGGGCCGGTCACATA | Reverse | 710 |

| LSU_Sep_530_Fwd | AAGACCTTAGGAATGTAGCTCACCT | Forward | 999 |

| LSU_Sep_530_Rev | AGGTGAGCTACATTCCTAAGGTCTT | Reverse | 999 |

| LSU_Sep_575_Fwd | CTTGGGCGAGGTCCGCGCT | Forward | 1059 |

| LSU_Sep_575_Rev | AGCGCGGACCTCGCCCAAG | Reverse | 1059 |

| LSU_Sep_785_Rev | AGGACATCAGGATCGGTCGAT | Reverse | 1225 |

Annotation: ITS1 = 1–172 bp, 5.8S = 173–330 bp, ITS2 = 331–525 bp, LSU D1 & D2 domain = 525–1110 bp.

A comparison between the full-length S. cytisi ITS sequence and 287 other Septoria ITS sequences that were generated as part of a larger unpublished study, broadly linked S. cytisi to a distinct ITS clade containing S. astralagi and S. hippocastani, basal to a clade consisting of the majority of sequenced Septoria species (data not shown). Interspecific variation in the S. cytisi ITS sequences were present; however, it was limited to a few nucleotides per isolate sequenced (Table 5).

Table 5.

Polymorphisms found in the ITS and LSU sequence between the S. cytisi herbarium specimens. Data marked with – are not available.

| BPI specimen | Collection year | ITS position (bp) |

LSU position (bp) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93 | 219 | 411 | 176 | 377 | 446 | 536 | 561 | 563 | ||

| USO 378989 | 1929 | A | – | – | T | T | G | T | T | C |

| USO 378993 | 1929 | A | C | C | C | C | C | A | G | – |

| USO 378994 | 1884 | C | G | T | C | C | G | A | G | G |

| USO 378990 | 1874 | A | G | C | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Amplification of the D1–D3 domains of the LSU region was attempted on the same S. cytisi gDNA extracts as mentioned before. A full-length sequence read of the S. cytisi D1–D3 domains (the first ± 900 bp of the 28S nrRNA gene) was only obtained from a single sample (US0378994). The four remaining herbarium specimens only yielded LSU sequences varying in length from 500–800 bp. Interspecific variation in the LSU nucleotide sequences was limited to a few nucleotides per sequenced isolate (Table 5).

Phylogenetic analyses

LSU dataset

During phylogenetic analyses, the S. cytisi LSU sequence was aligned with LSU sequence data of 64 Capnodiales taxa, including 19 representative Septoria taxa, in order to determine which of these Septoria isolates belonged to Septoria s.str. (i.e. high association with S. cytisi) and to establish how this clade is related to other well-established genera within the Capnodiales. For the LSU tree, ± 759 characters were determined for 64 Capnodiales taxa, including 19 Septoria taxa as well as the two Cladosporium bruhnei isolates that were used as outgroups (CPC 5101 and CBS 188.54). The phylogenetic analysis showed that 164 characters were parsimony-informative, 38 were variable and parsimony-uninformative and 557 were constant. Thirty-two equally most parsimonious trees were obtained from the heuristic search, the first of which is shown in Fig. 3 (TL = 574, CI = 0.495, RI = 0.848, RC = 0.419). The phylogenetic analysis of the Capnodiales LSU dataset, including S. cytisi, showed this species clustering in a well-defined clade incorporating the majority of the Septoria spp. used in this analysis, clearly delineating this clade as Septoria s.str. These results also show a distinct monophyletic clade that are referred to as Zymoseptoria gen. nov. below, which contains S. tritici and S. passerinii together with two other species in this genus.

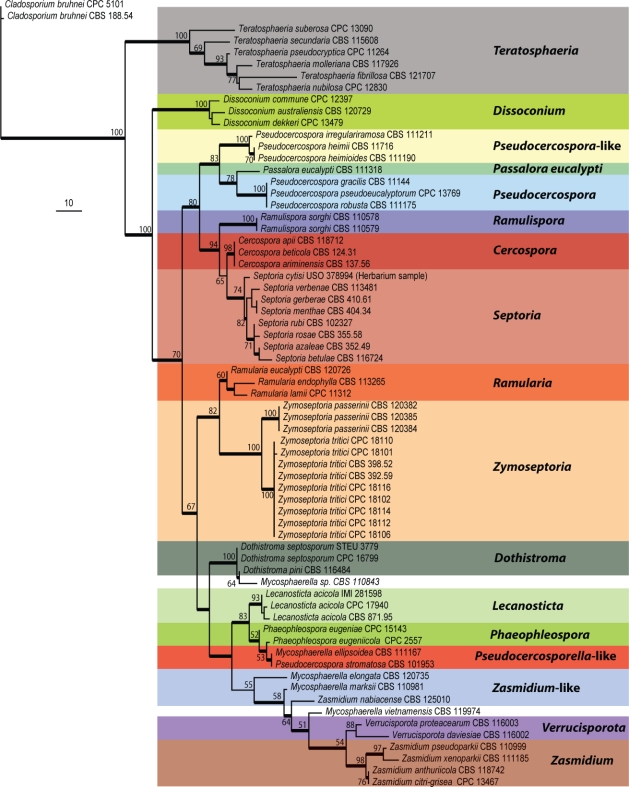

Fig. 3.

The first of 32 equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search with 1 000 random taxon additions of the LSU alignment containing representative species that currently form well-supported clades within the Capnodiales. The scale bar indicates 10 changes and bootstrap support values from 1 000 replicates are indicated at the nodes. Thickened lines indicate conserved branches present in the strict consensus tree.

Multi-locus dataset

For the multi-locus phylogenetic analyses of the graminicolous isolates, ± 220 nucleotides where determined for ACT, 345 for CAL, 513 for ITS, 350 for TUB, and 305 for RPB2 (see Table 3 for detailed primer description). The adjusted sequence alignment for each locus consisted of 69 ingroup taxa with Ramularia endophylla (Mycosphaerella punctiformis; strain CBS 113265) as outgroup.

The strict consensus tree (Fig. 4) based on the multi-locus maximum-parsimony analysis had an identical topology to those of the strict consensus trees obtained for the individual loci. The partition homogeneity tests for all of the possible combinations of the five gene regions consistently yielded a P-value of 0.001, and were therefore incongruent. However, the 70 % reciprocal bootstrap trees of the individual gene regions showed no conflicting tree topologies between the separate datasets. Based on the result of the 70 % reciprocal bootstrap trees (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996, Cunningham 1997), the DNA sequences of the five gene regions (ACT, CAL, RPB2, TUB and ITS) were concatenated for the phylogenetic analyses.

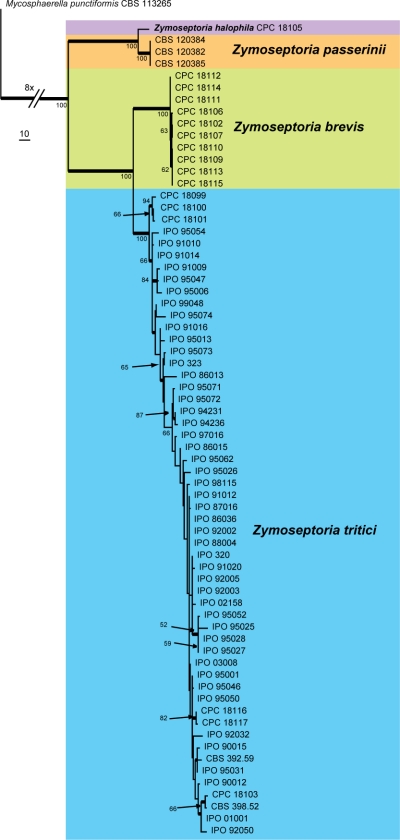

Fig. 4.

The first of 810 equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search with 1 000 random taxon additions of the combined ACT, CAL, TUB, RPB2 and ITS sequence alignment of Zymoseptoria spp. The scale bar indicates 10 changes and bootstrap support values from 1 000 replicates are indicated at the nodes. Thickened lines indicate conserved branches present in the strict consensus tree.

The concatenated and manually aligned multi-locus alignment contained 70 taxa (including the outgroup sequence) and, out of the 1 723 characters used in the phylogenetic analysis, 233 were parsimony-informative, 291 were variable and parsimony-uninformative and 1 199 were constant. 810 equally parsimonious trees were obtained from the heuristic search, the first of which is shown in Fig. 4 (TL = 768, CI = 0.815, RI = 0.922, RC = 0.751). Phylogenetic results showed two well-supported new species emerging besides the conserved S. tritici and S. passerinii clades, with a significant amount of genetic variation within the S. tritici clade as previously found by Goodwin et al. (2007). This intraspecific variation is most likely the cause of the partition homogeneity test failure.

The overall genetic diversity of S. tritici, examined over five loci, was found to be quite significant within the 54 global isolates of S. tritici used for this study. Most of the existing phylogenetic variation observed between the S. tritici isolates used in the combined tree (Fig. 4) was caused by single insertion and deletion events of triplets within tandem repeats inside the ACT and RPB2 intron sequences of these isolates. The most significant impact of these indel events can be seen in the phylogenetic cluster containing CPC 18099–18101 (on Aegilops tauschii, Iran), that arises in the S. tritici clade of the combined tree (Fig. 4). This small clade has a bootstrap support value of 94 %, suggesting that it could represent a cryptic or ancestral lineage of what is currently considered to be S. tritici. Further study using more isolates would be required to address this issue.

Taxonomy

Based on the LSU dataset (Fig. 3), S. cytisi was shown to cluster within the major Septoria clade, while the taxa occurring on graminicolous hosts clustered in a separate clade, distinct from Septoria (S. cytisi) and Mycosphaerella (M. punctiformis, represented by R. endophylla), suggesting that they represented a distinct genus in the Mycosphaerellaceae. Morphologically these phylogenetic differences were supported by the distinct yeast-like growth exhibited in culture by the graminicolous species, as well as their mode of conidiogenesis, e.g. phialidic, with periclinal thickening and occasional inconspicuous percurrent proliferation(s), but lacking blastic sympodial proliferation which occurs in many species of Septoria s.str. Based on these differences in culture, morphology and phylogeny, a new genus is hereby introduced for the taxa occurring on graminicolous hosts.

Zymoseptoria Quaedvlieg & Crous, gen. nov. — MycoBank MB517922

Septoriae similis, sed adaucto fermentoide, sine formatione blastica-sympodiali conidiorum, in cultura typis conidiorum usque ad 3.

Type species. Zymoseptoria tritici (Desm.) Quaedvlieg & Crous.

Etymology. Zymo = yeast-like growth; Septoria = Septoria-like in morphology.

Conidiomata pycnidial, semi-immersed to erumpent, dark brown to black, subglobose, with central ostiole; wall of 3–4 layers of brown textura angularis. Conidiophores hyaline, smooth, 1–2-septate, or reduced to conidiogenous cells, lining the inner cavity. Conidiogenous cells tightly aggregated, ampulliform to doliiform or subcylindrical, phialidic with periclinal thickening, or with 2–3 inconspicuous, percurrent proliferations at apex. Type I conidia solitary, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, narrowly cylindrical to subulate, tapering towards acutely rounded apex, with bluntly rounded to truncate base, transversely euseptate; hila not thickened nor darkened. On OA and PDA aerial hyphae disarticulate into phragmospores (Type II conidia), that again give rise to Type I conidia via microcyclic conidiation; yeast-like growth and microcyclic conidiation (Type III conidia) common on agar media.

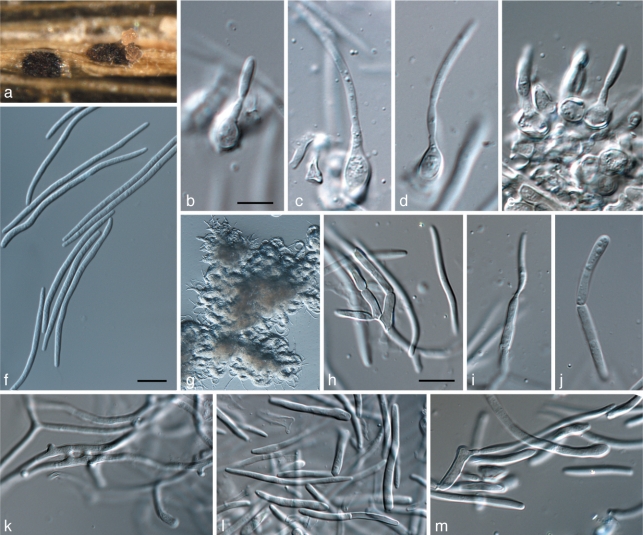

Zymoseptoria brevis M. Razavi, Quaedvlieg & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB517923; Fig. 5

Fig. 5.

Zymoseptoria brevis (CPC 18106) a. Pycnidium forming on barley leaves in vitro; b. colony sporulation on potato-dextrose agar; c. conidiogenous cells; d. colony on synthetic nutrient-poor agar, showing yeast-like growth; e. conidium undergoing microcyclic conidiation (arrows; Type III); f–h. pycnidiospores (Type I). — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Zymoseptoriae passerinii similis, sed conidiis minoribus, (12–)13–16(–17) × 2(–2.5) μm.

Etymology. Named after its conidia, which are shorter (brevis) than those of the other species.

On sterile barley leaves on WA: Conidiomata pycnidial, substomatal, immersed to erumpent, globose, dark brown, up to 200 μm diam, with central ostiole, 5–10 μm diam; wall of 3–4 layers of brown textura angularis. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells, or with one supporting cell, lining the inner cavity. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, tightly aggregated, subcylindrical to ampulliform, straight to curved, 7–15 × 2–4 μm, with 1–2 inconspicuous, percurrent proliferations at apex, 1–1.5 μm diam. Type I conidia solitary, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, subcylindrical to subulate, tapering towards bluntly rounded apex, with truncate base, 0–1-septate, (12–)13–16(–17) × 2(–2.5) μm; on PDA, 9–21 × 2–3.5 μm; hila not thickened nor darkened, 1–2 μm. On OA and PDA yeast-like growth and microcyclic conidiation (Type III conidia) common, also forming on aerial hyphae via solitary conidiogenous loci.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA flat, spreading, with moderate aerial mycelium and feathery, lobate margins; surface olivaceous-grey, outer region dirty white, reverse iron-grey; on MEA more erumpent, with less aerial mycelium; surface iron-grey with patches of white, reverse greenish black; on OA somewhat fluffy with dirty white to pale olivaceous aerial mycelium, and submerged, olivaceous-grey margin; reaching 15 mm diam after 1 mo at 25 °C; fertile.

Specimen examined. Iran, Ilam province, Dehloran, on living leaves of Phalaris minor, M. Razavi, holotype CBS H-20542, cultures ex-type No 8S = CPC 18106 = CBS 128853.

Notes — Zymoseptoria brevis can easily be distinguished from the other taxa presently known within the genus based on its shorter conidia.

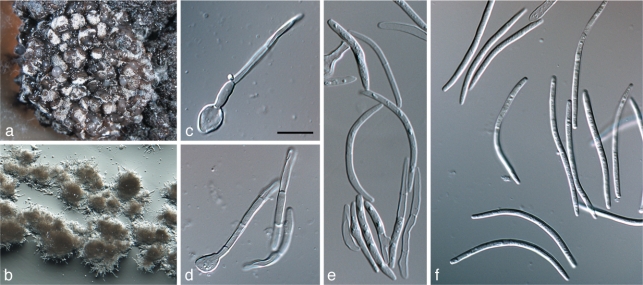

Zymoseptoria halophila (Speg.) M. Razavi, Quaedvlieg & Crous, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB517924; Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

Zymoseptoria halophila (CPC 18105). a. Pycnidia forming on barley leaves in vitro, with oozing conidia cirrhus; b–e. conidiogenous cells formed in pycnidia; f. conidia (Type I); g. colony with yeast-like growth on synthetic nutrient-poor agar; h, j–l. conidia formed as phragmospores in aerial hyphae (Type II); i, m. conidia formed via microcyclic conidiation (Type III). — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Basionym: Septoria halophila Speg., Anales Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Buenos Aires, Ser. 3, 13: 382. 1910.

Initial symptoms of the disease were dark-brown lesions which soon became pale buff in the centre. The leaves were heavily mottled later, and the solitary, sometimes aggregated pycnidia formed on the lesions. The disease was more severe on the lower leaves. Pycnidia were observed on adaxial surface of the infected leaves, and were dark-brown, globose, measuring 90–150 μm, with an ostiole ± 10 μm diam. On sterile barley leaves on WA: Conidiomata pycnidial, semi-immersed to erumpent, dark brown to black, subglobose, up to 300 μm diam, with central ostiole, up to 30 μm diam; wall of 3–4 layers of brown textura angularis. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells, lining the inner cavity. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, tightly aggregated, ampulliform to doliiform, 10–15 × 4–7 μm, with 2–3 inconspicuous, percurrent proliferations at apex, 1–2 μm diam. Type I conidia solitary, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, narrowly cylindrical to subulate, tapering towards acutely rounded apex, with bluntly rounded to truncate base; basal cell long obconically truncate, 1(–3)-septate, (30–)33–38(–50) × 2(–3) μm; conidia in vivo 1–2-septate, 36–45 × 1.5–2 μm; hila not thickened nor darkened, 1–2 μm. On OA and PDA conidia can be up to 62 μm long, and aerial hyphae disarticulate into phragmospores (Type II conidia), that again give rise to type I conidia via microcyclic conidiation; yeast-like growth and microcyclic conidiation (Type III conidia) common on agar media.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA flat, spreading, with sparse aerial mycelium and feathery, lobate margins; centre olivaceous-grey, outer region iron-grey; reverse iron-grey; on MEA surface and reverse greenish black; on OA iron-grey, reaching 20 mm diam after 1 mo at 25 °C; fertile.

Specimen examined. Iran, Ilam province, Dehloran, on living leaves of Hordeum glaucum, 25 Apr. 2007, M. Razavi, specimens IRAN12892F, CBS H-20543, cultures ex-type GLS1 = IRAN1483C = CPC 18105 = CBS 128854.

Notes — The present collection of Z. halophila was initially reported from Iran as S. halophila by Seifbarghi et al. (2009) (GenBank HM100267, HM100266), based on the description of S. halophila provided by Priest (2006). Zymoseptoria halophila was originally described from Hordeum halophilum collected in Argentina, with conidia being (0–)1(–2)-septate, 36–58 × 1.5(–2) μm, and conidiogenous cells being 8–10 × 2.5–3.5 μm. It is likely that the various collections on Hordeum and Poa spp. from Australia listed by Priest (2006) could represent different species, but this can only be resolved once additional collections and cultures have been obtained to facilitate further molecular comparisons.

Zymoseptoria halophila is closely related to Z. passerinii, which is also reflected in its conidial size, which overlaps in length, but can only be distinguished based on their difference in width. It is possible that some published records of Z. passerinii could in fact represent Z. halophila, but more collections would be required to resolve its host range and geographic distribution.

Zymoseptoria passerinii (Sacc.) Quaedvlieg & Crous, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB517925; Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Zymoseptoria passerinii (CBS 120382). a. Colony sporulating on potato-dextrose agar; b. colony sporulating on synthetic nutrient-poor agar; c. conidiogenous cells formed inside pycnidia; e, f. conidia from pycnidia (Type I). — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Basionym: Septoria passerinii Sacc., Syll. Fung. (Abellini) 3: 560. 1884.

Specimens examined. Italy, Vigheffio, near Parma, on Hordeum murinum, June 1879 (F. von Thümen, Mycotheca Univ. No. 1997, isotype in MEL, see Priest 2006, f. 107). – USA, North Dakota, Foster county, on Hordeum vulgare, coll. S. Goodwin, isol. D. Long, epitype designated here CBS H-20544, culture ex-epitype P83 = CBS 120382.

Notes — Priest (2006) reported Z. passerinii from several Hordeum species collected in Western Australia and deposited them at IMI (now in Kew), and found them to be identical to type material examined, suggesting that this pathogen is widely distributed along with its host. Ware et al. (2007) reported a Mycosphaerella-like teleomorph from a heterothallic mating of isolates of Z. passerinii. Single ascospore isolates have been deposited as CBS 120384 (P71 × P83A) and CBS 120385 (P71 × P83B). Isolate P63, which is genetically similar to P83 on the loci sequenced in this study, has been used for whole genome analysis of Z. passerinii (E.H. Stukenbrock, pers. comm.).

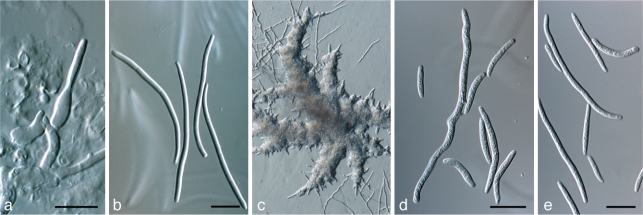

Zymoseptoria tritici (Desm.) Quaedvlieg & Crous, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB517926; Fig. 8

Fig. 8.

Zymoseptoria tritici (CBS 115943). a. Conidiogenous cells formed inside pycnidia; b. conidia from pycnidia (Type I); colony sporulating on synthetic nutrient-poor agar, showing yeast-like growth; d, e. conidia formed via microcyclic conidiation (Type III). — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Basionym: Septoria tritici Desm., Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 2, 17: 107 (1842).

Teleomorph: ‘Mycosphaerella’ graminicola (Fuckel) J. Schröt., in Cohn, Krypt.-Fl. Schlesien 3, 2: 340. 1894 (‘1893’).

Basionym: Sphaeria graminicola Fuckel, Fungi Rhenani Exsicc.: no. 1578. 1865.

≡ Sphaerella graminicola (Fuckel) Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 23–24: 101. 1870.

Specimens examined. France, on Triticum sp. (holotype of Septoria tritici; PC). – Germany, Oestrich, on Triticum repens, Fuckel, Fungi Rhenani Exsiccati no. 1578 (L, isotype of Mycosphaerella graminicola). – Netherlands, Brabant West, on Triticum aestivum, coll. R. Daamen, 6 May 1981, isol. as single conidium, W. Veenbaas, 810507/1, 7 May 1981, epitype designated here CBS H-20545, including teleomorph material on Triticum leaf of heterothallic mating IPO 323 (MAT 1-1) × IPO 94269 (MAT 1-2), culture ex-epitype IPO 323 = CBS 115943.

Notes — The isolate designated here as ex-epitype (IPO 323 = CBS 115943) is also the strain used in the whole genome amplification and sequencing of this species (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycgr3/Mycgr3.download.html).

DISCUSSION

For many years the genus Mycosphaerella has been treated as a wide general concept to accommodate a range of related and unrelated species and genera that have small ascomata, and hyaline, 1-septate ascospores, without pseudoparaphyses (Aptroot 2006). The observation that Mycosphaerella-like teleomorphs were linked to more than 40 different anamorphs (Crous 2009) was thus seen as rather odd, though acceptable within this wider concept used to accommodate these thousands of mostly phytopathogenic fungi. It was only in recent years when the higher order phylogenetic relationships of Mycosphaerella was addressed as part of the Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life initiative (Schoch et al. 2006), that Mycosphaerella was shown to be polyphyletic (Crous et al. 2007), even containing different families within the Dothideomycetes (Crous et al. 2009a, b, Schoch et al. 2009a, b).

The fact that Septoria also contains significant morphological variation was commented on by Sutton (1980), who stated that the genus is heterogeneous, and should be revised, containing conidiomata that ranged from acervuli to pycnidia, and conidiogenesis that ranged from blastic sympodial to annellidic (percurrent proliferation) or phialidic (with periclinal thickening). As can be seen with the taxa treated to date, however, these characters alone are also insufficient to delineate all natural genera, as several modes of conidiogenesis or conidiomatal types occur within the same genus in the Septoria-like complex. Part of the reason for the confusion surrounding the genus Septoria is based on the fact that until now no DNA sequence data were available for the type species, S. cytisi. Due to the lack of cultures of this species, DNA was subsequently extracted from several herbarium specimens. Using this technique, however, some intraspecific variation was observed in both the LSU and ITS sequences of S. cytisi. This could possibly be explained by geographical and temporal spread in the sampling sites, spanning 54 years from a region encompassing South and Central Europe, making some sequence variation within these specimens probable. Even if one or two nucleotides might actually be scored wrong in the US0378994-derived LSU sequence for S. cytisi, this would not have any impact on the phylogenetic position of S. cytisi within the Septoria s.str. clade, its nearest sister genus being Cercospora in the Mycosphaerellaceae (Groenewald et al. 2006).

As shown in the present study (Fig. 2), the genus Mycosphaerella is unavailable to accommodate the taxa occurring on graminicolous hosts, as Mycosphaerella is restricted to species with Ramularia anamorphs (Verkley et al. 2004a, Crous et al. 2009b). Furthermore, Septoria s.str. also clusters apart from the species on cereals (Fig. 3), making the name Septoria unavailable for these pathogens.

In the present study we introduce a novel genus Zymoseptoria to accommodate the Septoria-like species occurring on graminicolous hosts. Although species of Zymoseptoria tend to have phialides with apical periclinal thickening, this mode of conidiogenesis has also evolved in Septoria s.str. (e.g. S. apiicola), and is not restricted to Zymoseptoria. More importantly, species of Zymoseptoria exhibit a yeast-like growth in culture, and have up to three different conidial types that can be observed, namely Type I (pycnidial conidia), Type II (phragmospores on aerial hyphae), and Type III (yeast-like growth proliferating via microcyclic conidiation). Introducing a novel genus for this group of important plant pathogens was not taken lightly, as Z. passerinii causes septoria speckled leaf blotch (SSLB) on barley (Hordeum vulgare), and has been reported around the globe on this crop (Mathre 1997, Cunfer & Ueng 1999, Goodwin & Zismann 2001, Ware et al. 2007). Septoria tritici blotch (STB) is caused by Z. tritici (teleomorph ‘Mycosphaerella’ graminicola), and is currently present in all major wheat growing areas. This disease is consistently ranked amongst the most damaging wheat diseases in Australia, Europe, North and South America, and in Europe more than 70 % of all the fungicides applied to wheat are to control STB (Eyal et al. 1987). Wheat, together with maize and rice directly contribute 47 % to global human consumption (Tweeten & Thompson 2009). Since 1961, wheat production has increased globally with almost 300 % on a virtually stable cultivation area of 200 M ha. This progress was largely achieved by increased average yields (FAO 2010). However, the annual growth rate of global wheat production cannot meet the global market requirements in the coming four decades (Fischer et al. 2009, Fischer & Edmeades 2010).

Although Z. passerinii and Z. tritici share many similarities (Goodwin et al. 2001) (Fig. 3, 4), both pathogens having a dimorphic lifestyle (Mehrabi et al. 2006); one major difference between them is that Z. tritici has a year-round and very active sexual cycle (Shaw & Royle 1993, Kema et al. 1996, Zhan et al. 2003), whereas there have been no reports of a sexual cycle for S. passerinii observed in nature, despite isolates of S. passerinii having opposite mating types being commonly found in natural populations, even on the same leaf (Goodwin et al. 2003), suggesting cryptic sex does exist for Z. passerinii (Ware et al. 2007). With respect to the two additional species treated in the present study, Z. brevis and Z. halophila, almost nothing is known about their relative importance, geographical distribution, host range or sexual behaviour. Given the importance of their known host crops, however, this complex is in dire need of further study.

Acknowledgments

The curator of the US National Fungus Collection in Beltsville, Maryland USA (BPI) is gratefully acknowledged for permission to extract DNA from the herbarium specimens of S. cytisi, without which this study would not have been possible. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/grant agreement no. 226482 (Project: QBOL - Development of a new diagnostic tool using DNA barcoding to identify quarantine organisms in support of plant health) by the European Commission under the theme ‘Development of new diagnostic methods in support of Plant Health policy’ (no. KBBE-2008-1-4-01). Drs M. Abbasi, R. Zare and Mr M. Aminirad helped us in providing herbarium and fungal culture collection numbers, and identifying plant species at the Department of Botany, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection.

REFERENCES

- Aptroot A.2006. Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs: 2. Conspectus of Mycosphaerella. CBS Biodiversity Series 5: 1 – 231 [Google Scholar]

- Aveskamp MM, Verkley GJM, Gruyter J de, Murace MA, Perello A, et al. 2009. DNA phylogeny reveals polyphyly of Phoma section Peyronellaea and multiple taxonomic novelties. Mycologia 101: 363 – 382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun U.1998. A monograph of Cercosporella, Ramularia and allied genera (Phytopathogenic Hyphomycetes). Vol. 2 IHW-Verlag, Eching: [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM.1999. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91: 553 – 556 [Google Scholar]

- Cheewangkoon R, Crous PW, Hyde KD, Groenewald JZ, Toanan C.2008. Species of Mycosphaerella and related anamorphs on Eucalyptus leaves from Thailand. Persoonia 21: 77 – 91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW.2009. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the genus Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs. Fungal Diversity 38: 1 – 24 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Aptroot A, Kang J-C, Braun U, Wingfield MJ.2000. The genus Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs. Studies in Mycology 45: 107 – 121 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Braun U, Groenewald JZ.2007. Mycosphaerella is polyphyletic. Studies in Mycology 58: 1 – 32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Gams W, Stalpers JA, Robert V, Stegehuis G.2004. MycoBank: an online initiative to launch mycology into the 21st century. Studies in Mycology 50: 19 – 22 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Hong L, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD, Kang J.1999. Uwebraunia and Dissoconium, two morphologically similar anamorph genera with distinct teleomorph affinity. Sydowia 52: 155 – 166 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Kang JC, Braun U.2001. A phylogenetic redefinition of anamorph genera in Mycosphaerella based on ITS rDNA sequence and morphology. Mycologia 93: 1081 – 1101 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Schoch CL, Hyde KD, Wood AR, Gueidan C, et al. 2009a. Phylogenetic lineages in the Capnodiales. Studies in Mycology 64: 17 – 47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Summerell BA, Carnegie AJ, Wingfield MJ, Hunter GC, et al. 2009b. Unravelling Mycosphaerella: do you believe in genera? Persoonia 23: 99 – 118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Verkley GJM, Groenewald JZ, Samson RA. (eds). 2009c. Fungal Biodiversity. CBS Laboratory Manual Series 1: 1–269. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, Netherlands: [Google Scholar]

- Cunfer BM, Ueng PP.1999. Taxonomy and identification of Septoria and Stagonospora species on small grain cereals. Annual Review of Phytopathology 37: 267 – 284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CW.1997. Can three incongruence tests predict when data should be combined? Molecular Biology and Evolution 14: 733 – 740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal Z, Sharen AL, Prescott JM, Ginkel M van.1987. The Septoria diseases of wheat: concepts and methods of disease management. Mexico, DF, CIMMYT; [Google Scholar]

- FAO 2010 http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor

- Farris JS, Källersjö M, Kluge AG, Bult C.1994. Testing significance of incongruence. Cladistics 10: 315 – 319 [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RA, Byerlee D, Edmeades GO.2009. Can technology deliver on the yield challenge to 2050? Prepared for UN FAO Expert Meeting on How to Feed the World in 2050 Rome, 24–26 June 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RA, Edmeades GO.2010. Breeding and cereal yield progress. Crop Science 50: S85 – S98 [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SB, Dunkle LD, Zismann VL.2001. Phylogenetic analysis of Cercospora and Mycosphaerella based on the internal transcribed spacer region of ribosomal DNA. Phytopathology 91: 648 – 658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SB, Lee TAJ van der, Cavaletto JR, Hekkert BTL, Crane CF, Kema GHJ.2007. Identification and genetic mapping of highly polymorphic microsatellite loci from an EST database of the septoria tritici blotch pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Fungal Genetics and Biology 44: 398 – 414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SB, Waalwijk C, Kema GHJ, Cavaletto JR, Zhang G.2003. Cloning and analysis of the mating-type idiomorphs from the barley pathogen Septoria passerinii. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 269: 1 – 12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SB, Zismann VL.2001. Phylogenetic analyses of the ITS region of ribosomal DNA reveal that Septoria passerinii from barley is closely related to the wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Mycologia 93: 934 – 946 [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald M, Groenewald JZ, Braun U, Crous PW.2006. Host range of Cercospora apii and C. beticola, and description of C. apiicola, a novel species from celery. Mycologia 98: 275 – 285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kema GHJ, Verstappen ECP, Todorova M, Waalwijk C.1996. Successful crosses and molecular tetrad progeny analyses demonstrate heterothallism in Mycosphaerella graminicola. Current Genetics 30: 251 – 258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner R.2009. Cercosporella and Ramularia. Mycologia 101: 110 – 119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Whelen S, Hall B.1999. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Molecular Biology and Evolution 16: 1799 – 1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard L, Crous PW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ.2010. Multigene phylogeny and mating tests reveal three cryptic species related to Calonectria pauciramosa. Studies in Mycology 66: 15 – 30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason-Gamer RJ, Kellogg EA.1996. Testing for phylogenetic conflict among molecular data sets in the tribe Triticeae (Gramineae). Systematic Biology 45: 524 – 545 [Google Scholar]

- Mathre DE.1997. Compendium of barley diseases. Second edn American Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi R, Zwiers LH, Waard M de, Kema GHJ.2006. MgHog1 regulates dimorphism and pathogenicity in the fungal wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 19: 1262 – 1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RDM.1996. TREEVIEW: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Computer Applications in the Biosciences 12: 357 – 358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA.1998. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14: 817 – 818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest MJ.2006. Septoria. Fungi of Australia. ABRS, Canberra: CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia: [Google Scholar]

- Rayner RW.1970. A mycological colour chart. CMI and British Mycological Society; Kew, Surrey, England: [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Boehm EWA, Burgess TI, et al. 2009a. A class-wide phylogenetic assessment of Dothideomycetes. Studies in Mycology 64: 1 – 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Shoemaker RA, Seifert KA, Hambleton S, Spatafora JW, Crous PW.2006. A multigene phylogeny of the Dothideomycetes using four nuclear loci. Mycologia 98: 1041 – 1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Sung GH, López-Giráldez F, Townsend JP, Miadlikowska J, et al. 2009b. The Ascomycota tree of life: a phylum wide phylogeny clarifies the origin and evolution of fundamental reproductive and ecological traits. Systematic Biology 58: 224 – 239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifbarghi S, Razavi M, Aminian H, Zare R, Etebarian H.2009. Studies on the host range of Septoria species on cereals and some wild grasses in Iran. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 48: 422 – 429 [Google Scholar]

- Shaw MW, Royle DJ.1993. Factors determining the severity of epidemics of Mycosphaerella graminicola (Septoria tritici) on winter wheat in the UK. Plant Pathology 42: 882 – 899 [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EL, Liu Z, Crous PW, Szabo L.1999. Phylogenetic relationships among some cercosporoid anamorphs of Mycosphaerella based on rDNA sequence analysis. Mycological Research 103: 1491 – 1499 [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC.1980. The coelomycetes. Fungi imperfecti with Pycnidia, Acervuli and Stromata. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surrey, England: [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL.2003. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Tweeten L, Thompson S.2009. Long-term global agricultural output supply-demand balance and real farm and food prices. Farm Policy Journal 6 [Google Scholar]

- Verkley GJM, Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Braun U, Aptroot A.2004a. Mycosphaerella punctiformis revisited: morphology, phylogeny, and epitypification of the type species of the genus Mycosphaerella (Dothideales, Ascomycota). Mycological Research 108: 1271 – 1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkley GJM, Priest MJ.2000. Septoria and similar coelomycetous anamorphs of Mycosphaerella. Studies in Mycology 45: 123 – 128 [Google Scholar]

- Verkley GJM, Starink-Willemse M, Iperen A van, Abeln ECA.2004b. Phylogenetic analyses of Septoria species based on the ITS and LSU-D2 regions of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Mycologia 96: 558 – 571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M.1990. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172: 4238 – 4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware SB, Verstappen ECP, Breeden J, Cavaletto JR, Goodwin SB, et al. 2007. Discovery of a functional Mycosphaerella teleomorph in the presumed asexual barley pathogen Septoria passerinii. Fungal Genetics and Biology 44: 389 – 397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan J, Pettway RE, McDonald BA.2003. The global genetic structure of the wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola is characterized by high nuclear diversity, low mitochondrial diversity, regular recombination, and gene flow. Fungal Genetics and Biology 38: 286 – 297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]