Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Emerging epidemiological evidence suggests that higher magnesium intake may reduce diabetes incidence. We aimed to examine the association between magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes by conducting a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We conducted a PubMed database search through January 2011 to identify prospective cohort studies of magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also reviewed. A random-effects model was used to compute the summary risk estimates.

RESULTS

Meta-analysis of 13 prospective cohort studies involving 536,318 participants and 24,516 cases detected a significant inverse association between magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes (relative risk [RR] 0.78 [95% CI 0.73–0.84]). This association was not substantially modified by geographic region, follow-up length, sex, or family history of type 2 diabetes. A significant inverse association was observed in overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) but not in normal-weight individuals (BMI <25 kg/m2), although test for interaction was not statistically significant (Pinteraction = 0.13). In the dose-response analysis, the summary RR of type 2 diabetes for every 100 mg/day increment in magnesium intake was 0.86 (95% CI 0.82–0.89). Sensitivity analyses restricted to studies with adjustment for cereal fiber intake yielded similar results. Little evidence of publication bias was observed.

CONCLUSIONS

This meta-analysis provides further evidence supporting that magnesium intake is significantly inversely associated with risk of type 2 diabetes in a dose-response manner.

Type 2 diabetes has been a growing public health burden across the world, particularly in the developing countries (1). In China, for instance, diabetes has reached epidemic proportions, affecting ∼92.4 million people aged ≥20 years (9.7% of the adult population) (2). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop primary prevention strategies aimed at controlling this epidemic.

Diet is widely believed to play an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes (3,4). Magnesium, an important component of many foods, such as whole grains, nuts, and green leafy vegetables, is an essential cofactor for enzymes involved in glucose metabolism (5). Magnesium has received considerable interest for its potential in improving insulin sensitivity and preventing diabetes (6,7). A number of prospective cohort studies (8–19) of magnesium intake and diabetes incidence have been conducted, but the results are inconsistent. One previous meta-analysis (14) of eight studies reported a significant inverse association between magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. Another meta-analysis (20) of seven studies quantified a dose-response relationship for this association. However, it remains unclear whether overweight, an established risk factor of type 2 diabetes (21,22), affects the association and whether other factors highly correlated to magnesium intake, such as cereal fiber (14) and calcium (23), are responsible for the observed association.

During the past few years, the number of subsequent primary studies on this topic has nearly doubled. With mounting evidence, we conducted a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies for the following purposes: 1) to update the epidemiologic evidence on the association between magnesium intake and type 2 diabetes; 2) to examine this association according to characteristics of study designs and populations; and 3) to quantify a dose-response pattern of magnesium intake on diabetes risk.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Literature search

We attempted to report this study in accordance with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (24) for meta-analyses of observational studies. We searched the PubMed database through January 2011, using the key word magnesium in combination with diabetes, and examined the reference lists of the obtained articles. No restriction was imposed. When necessary, we contacted authors of original studies for additional data.

Study selection

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: the study design was a prospective cohort study; the exposure of interest was intake of dietary magnesium or total magnesium (dietary and supplemental); the outcome of interest was incidence of type 2 diabetes; and the risk estimate of type 2 diabetes related to magnesium intake and associated 95% CI were reported.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We used a standardized data collection form to extract the following information: author name; publication year; study population, location, and length of follow-up; number of cases and participants; assessment of exposure and outcome; most fully adjusted risk estimate from multivariable model for the highest versus the lowest category of magnesium intake with corresponding 95% CI; and statistical adjustment for the main confounding factors of interest. In one study (8), we used data from the multivariable model with full control for potential confounders but not for insulin and glucose because magnesium plays an important role in insulin action and glucose homeostasis (5), and adjustment for insulin and glucose, therefore, could represent overadjustment for variables on the causal pathway. Two authors (J.-Y.D. and L.-Q.Q.) independently performed the literature search, study selection, and data extraction. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

The relative risk (RR) was used as the common measure of association across studies, and the hazard ratio and incidence rate ratio were considered directly as RR. Homogeneity test was performed with the use of Q statistic at the P < 0.10 level of significance. We also calculated the I2 statistic, a quantitative measure of inconsistency across studies (25). Because of the presence of heterogeneity across studies, a random-effects model, which considered both within- and between-study variation, was used to compute the summary risk estimate.

Prespecified subgroup analyses according to geographic region, length of follow-up, sex, family history of diabetes, and BMI were performed to examine the impacts of these factors on the association. To test the robustness of the association, we also performed sensitivity analyses restricted to studies on dietary magnesium only and studies with further adjustment for cereal fiber intake. In addition, we examined the influence of a single study on the summary risk estimate by omitting one study in each turn.

We next quantified a potential linear dose-response relationship of magnesium intake to diabetes risk because most individual studies have detected a significant linear trend. We first calculated an RR for every 100 mg/day increment in magnesium intake for each study based on the method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker (26). These RRs across studies were then combined to obtain a summary estimate.

Potential publication bias was assessed by Begg rank correlation test and Egger linear regression test (27,28). All analyses were performed using STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All statistical tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, except where otherwise specified.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

We identified 13 prospective cohort studies (8–19) of magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes—one article (11) included two separate cohort studies—involving 536,318 participants and 24,516 incident cases. All studies reported type 2 diabetes as the primary outcome except one study (17) that did not specify diabetes type (the great majority of participants had type 2 diabetes). Characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Table 1. The 13 prospective cohort studies were published between 1999 and 2010. Of them, eight studies were conducted in the United States, three in Asia, one in Europe, and one in Australia. The number of cases diagnosed in the primary studies ranged from 330 to 8,587, and the number of participants ranged from 4,497 to 85,060. Both men and women were included in seven studies, one study consisted of men only, and five studies consisted of women only. Of the studies, nine reported results on dietary magnesium intake, two (11) on total (dietary and supplemental) magnesium intake, and two (12,17) on both dietary and total magnesium intake. Intake of supplemental magnesium was assessed from use of magnesium or multivitamin supplements; however, dietary magnesium accounted for the majority of total magnesium intake.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 13 prospective cohort studies of magnesium and type 2 diabetes

| Study | Population (cases) | Duration (years) | Dietary assessment method | Case ascertainment | Magnesium intake (highest vs. lowest, mg/day) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjustment for potential confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kao et al., 1999 (8) | 11,896 adults aged 45–64 years, U.S. (1,106) | 6 | Validated FFQ | Glucose levels, use of diabetic medication, and self-report | 361 vs. 154 | White: 1.08 (0.78–1.49); black: 0.98 (0.57–1.72) | Age, BMI, sex, education, family history, WHR, sports index, diuretic use, and intakes of alcohol, calcium, and potassium |

| Meyer et al., 2000 (9) | 35,988 women aged 55–69 years, U.S. (1,141) | 6 | Validated FFQ | Self-report | 362 vs. 220 | 0.67 (0.55–0.82) | Age, BMI, education, smoking, WHR, physical activity, intakes of total energy, alcohol, whole grains, and cereal fiber |

| Hodge et al., 2004 (10) | 34,641 adults aged 40–69 years, Australia (365) | 4 | FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 773 vs. 230 | 0.55 (0.32–0.97) | Age, BMI, sex, education, country of birth, family history, WHR, weight change, physical activity, and intakes of total energy and alcohol |

| Lopez-Ridaura et al., 2004 (11) | 42,872 men aged 40–75 years, U.S. (1,333) | 11 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 457 vs. 270 | 0.72 (0.58–0.89) | Age, BMI, family history, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, physical activity, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, glycemic load, PUFA, TFA, processed meat, and cereal fiber |

| Lopez-Ridaura et al., 2004 (11) | 85,060 women aged 30–55 years, U.S. (4,085) | 17 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 374 vs. 222 | 0.73 (0.65–0.82) | Age, BMI, family history, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, physical activity, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, glycemic load, PUFA, TFA, processed meat, and cereal fiber |

| Song et al., 2004 (12) | 38,025 women aged ≥45 years, U.S. (918) | 6 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 399 vs. 252 | 0.89 (0.71–1.10) | Age, BMI, family history, smoking, physical activity, and intakes of total energy and alcohol |

| van Dam et al., 2006 (13) | 41,186 women aged 21–69 years, U.S. (1,964) | 6 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 244 vs. 115 | 0.65 (0.54–0.78) | Age, BMI, education, family history, smoking, physical activity, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, coffee, sugar-sweetened drinks, red meat, processed meat, and calcium |

| Schulze et al., 2007 (14) | 25,067 adults aged 35–65 years, Germany (844) | 7 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 377 vs. 268 | 0.99 (0.78–1.26) | Age, BMI, sex, education, sports activity, cycling, occupational activity, smoking, WC, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, carbohydrate, PUFA-to-SFA ratio, MUFA-to-SFA ratio, and cereal fiber |

| Villegas et al., 2009 (15) | 64,191 women aged 40–70 years, China (2,270) | 6.9 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 318 vs. 214 | 0.80 (0.68–0.93) | Age, BMI, WHR, smoking, physical activity, income, education, occupation, hypertension, and intakes of total energy and alcohol |

| Hopping et al., 2010 (16) | 75,512 men aged 45–75 years, U.S. (8,587) | 14 | FFQ | Glucose levels, use of diabetic medication, and self-report | 370 vs. 260 | Men: 0.77 (0.70–0.85); women: 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | BMI, physical activity, education, ethnicity, and total energy intake |

| Kim et al., 2010 (17) | 4,497 adults aged 18–30 years, U.S. (330) | 20 | Validated diet history questionnaire | Glucose levels and use of diabetic medication | 403 vs. 200 | 0.53 (0.32–0.86) | Age, BMI, sex, ethnicity, study center, education, smoking, physical activity, family history, systolic blood pressure, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, saturated fat, and crude fiber |

| Kirii et al., 2010 (18) | 17,592 adults aged 40–65 years, Japan (459) | 5 | Validated dietary questionnaire | Confirmed self-report | 303 vs. 158 | 0.64 (0.44–0.94) | Age, BMI, family history, smoking, hours of walking and sports participation, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, green tea, and coffee |

| Nanri et al., 2010 (19) | 59,791 men aged 45–75 years, Japan (1,114) | 5 | Validated FFQ | Confirmed self-report | 348 vs. 213 | Men: 0.86 (0.63–1.16); women 0.92 (0.66–1.28) | Age, BMI, study area, smoking, family history, leisure time physical activity, hypertension, and intakes of total energy, alcohol, coffee, and calcium |

FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SFA, saturated fatty acid; TFA, trans fatty acid; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

The mean length of follow-up ranged from 4 to 20 years. Most studies used validated food-frequency questionnaires in dietary assessment. Diabetes ascertainment was largely based on self-reports of physician diagnosis, but the majority of cases were confirmed in validation studies. The major adjusted confounders included age, BMI, physical activity, total energy intake, alcohol consumption, smoking, education, and family history of diabetes. Adjusted dietary confounders were varied across individual studies, whereas cereal fiber intake was adjusted for in five studies (9,11,14,17).

Main analysis

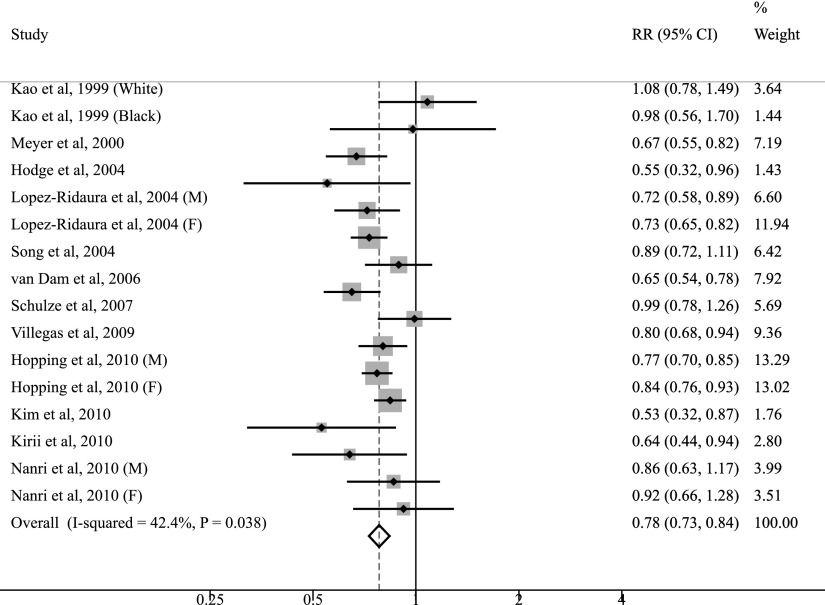

The multivariable-adjusted RRs of type 2 diabetes for each study and all studies combined for the highest versus the lowest category of magnesium intake are shown in Figure 1. Of the 13 selected studies, 9 found a statistically significant inverse association between magnesium intake and diabetes risk. The summary RR of type 2 diabetes was 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.84), comparing the highest with the lowest category of magnesium intake. Substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies (Pheterogeneity = 0.04, I2 = 42.4%).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of prospective cohort studies examining magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. M, male; F, female.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Table 2 presents the results of subgroup analyses stratified by characteristics of study designs and populations. Overall, the inverse association between magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes was not substantially modified by geographic region, follow-up length, sex, or family history of diabetes. Notably, the observed inverse association was more pronounced among participants with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (RR 0.73 [95% CI 0.66–0.81]), and there was little evidence of heterogeneity (Pheterogeneity = 0.21, I2 = 28.1%). However, no association was observed among those with BMI <25 kg/m2 (RR 1.09 [0.76–1.56]).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses relating magnesium to type 2 diabetes by characteristics of study designs and populations

| Group | Number of studies | RR (95% CI) | P | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) | Pinteraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 13 | 0.78 (0.73–0.84) | <0.001 | 0.04 | 42.4 | |

| Geographic area | 0.64 | |||||

| U.S. | 8 | 0.77 (0.71–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.04 | 49.9 | |

| Asia | 3 | 0.81 (0.71–0.91) | 0.001 | 0.53 | 0 | |

| Duration (years) | 0.93 | |||||

| ≤6 | 7 | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.05 | 48.9 | |

| >6 | 6 | 0.78 (0.75–0.82) | <0.001 | 0.12 | 40.2 | |

| Sex | 0.95 | |||||

| Men | 5 | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0 | |

| Women | 9 | 0.76 (0.70–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.06 | 47.1 | |

| Family history of diabetes | 0.83 | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0 | |

| No | 4 | 0.71 (0.62–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.31 | 15.7 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.13 | |||||

| <25 | 3 | 1.09 (0.76–1.56) | 0.76 | 0.12 | 52.9 | |

| ≥25 | 6 | 0.73 (0.66–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.21 | 28.1 |

To test the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses. Restricting analysis to studies of dietary magnesium intake yielded an RR of 0.80 (95% CI 0.70–0.86; n = 11). Restricting analysis to studies that controlled for cereal fiber yielded an RR of 0.74 (0.68–0.80; n = 5). Further analyses investigating the influence of a single study on the overall risk estimate by omitting one study at each turn yielded a narrow range of RRs from 0.77 (0.72–0.82) to 0.79 (0.74–0.85). In addition, no single study substantially contributed to the heterogeneity across studies.

Dose-response analysis

In the dose-response analysis of the 13 primary studies, the summary RR of type 2 diabetes for every 100 mg/day increment in magnesium intake was 0.86 (95% CI 0.82–0.89), with evidence of heterogeneity among studies (Pheterogeneity = 0.02, I2 = 48.4%).

Publication bias

There was little evidence of publication bias with regard to magnesium intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes, as indicated by Begg rank correlation test (P = 0.99) and Egger linear regression test (P = 0.95).

CONCLUSIONS

In the past decade, the role of magnesium in development of type 2 diabetes has been increasingly recognized. The present updated meta-analysis of 13 prospective cohort studies involving 536,318 participants and 24,516 cases determined a significant inverse association between magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in a dose-response manner.

Substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies, which was expected given the between-study variation, such as inconsistent data collecting methods, various nutrient databases, and different ethnic populations. In our subgroup analyses, the results were not substantially affected by geographic region, follow-up length, sex, or family history of diabetes, whereas the association tended to be stronger in overweight than in normal-weight individuals. The absence of heterogeneity in the stratified analyses by BMI indicated that BMI may, at least partially, contribute to the overall between-study variation. More important, BMI may serve as an effect modifier of the magnesium and diabetes association. All included cohort studies have adjusted for BMI, but only six studies (11,12,17–19) have assessed the impacts of BMI on the association between magnesium intake and diabetes risk. Among them, three studies (12,17,18) found more pronounced associations in overweight individuals than in normal-weight ones, yet only one (12) reached statistical significance in interaction tests. In our stratified analyses, the effect of BMI on the association was apparent, although the test for interaction was not statistically significant (Pinteraction = 0.13), which was likely the result of insufficient statistical power. Of note, it is plausible that high magnesium intake may have greater effects on improving insulin sensitivity in overweight individuals who are prone to insulin resistance (12). In this regard, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio, which are suggested to be better predictors of insulin resistance than BMI (29), may have more pronounced effects on the magnesium and diabetes association.

Because magnesium intake highly correlated to other healthy lifestyle and dietary factors, such as cereal fiber and calcium intakes, it is difficult to isolate the effect of magnesium intake on diabetes risk from other factors. Consequently, the potential influences of these factors deserve consideration while interpreting the results. Higher cereal fiber intake has been shown to be associated with a reduced diabetes risk (14). In our analysis restricted to five studies (9,11,14,17) with control for cereal fiber intake, the inverse association between magnesium intake and diabetes risk persisted and remained statistically significant. In addition, limited evidence suggests calcium intake may play a role in preventing diabetes (23). However, in the Black Women’s Health Study (13) that mutually adjusted for magnesium and calcium, the association between calcium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes disappeared, whereas an inverse association with magnesium intake remained. Moreover, physical activity (11,15) and smoking (15,18), two important and modifiable risk factors for diabetes (30,31), appeared not to have appreciable impacts on the association. Taken together, existing evidence to date from observational cohort studies supports an independent, protective role of magnesium intake against type 2 diabetes.

Indeed, experimental and metabolic studies have provided convincing evidence in support of direct effects of magnesium intake on insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Intracellular magnesium deficiency may result in disorders of tyrosine kinase activity during insulin signaling and glucose-induced insulin secretion, leading to impaired insulin sensitivity in muscle cells and adipocytes (32,33). In animal studies, magnesium supplementation has been shown to protect against fructose-induced insulin resistance (6) and reduce the development of diabetes in rat models (7). Furthermore, evidence from randomized controlled studies suggests that magnesium supplementation may exert beneficial effects on glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes (34) and improve insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic subjects (35–37).

Our findings confirmed results from previous meta-analyses (14,20). With the accumulative evidence, we were able to enhance the precision of the risk estimates and perform subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity, thereby increasing the clinical relevance of our findings (38). Also, all included studies used a prospective cohort design, which minimized the likelihood of recall and selection biases. In addition, the presence of dose-response relationship strengthened the association of magnesium intake with risk of type 2 diabetes.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, observational studies cannot establish causal association, and residual confounding remains a concern. A wide range of potential confounders, including demographic and lifestyle factors, were adjusted for in the primary studies, whereas dietary factors were not sufficiently considered. Therefore, we could not fully exclude the possibility that unmeasured or inaccurately measured dietary factors are responsible for the observed association. Second, misclassification bias may have weakened the strength of the association. Because dietary assessment was based on self-administered questionnaires, misclassification of dietary magnesium intake is inevitable. Misclassification of diabetes cases is also likely to occur given that diabetes ascertainments in most studies were based on self-reports. Few studies (11,15,17,19) repeated dietary assessment during the follow-up period, which may also result in misclassification. Third, we could not completely rule out the influences of changes in diet on the risk estimate in those with subclinical diabetes at baseline. Sensitivity analyses that excluded cases diagnosed within the initial several years of follow-up would help examine these influences and achieve more reliable results, but they were performed in few studies (15). Finally, publication bias could affect results of meta-analyses. However, minimal evidence of this bias was detected in our meta-analysis.

Our findings have implications for further research and are of public health significance. Apart from adequate control for potential confounders, particularly dietary factors, subsequent cohort studies of magnesium intake and type 2 diabetes should take the potential effect modification by BMI into consideration. Individual-level meta-analyses (39) with more power to detect effect modification than study-level meta-analyses may also be pursued. To date, large scale, randomized, placebo-controlled trials, which provide the strongest evidence for establishing a causal relation (40), have not been carried out to directly evaluate the effect of magnesium on diabetes incidence. Given the compelling evidence from the observational studies, such trials are anticipated to draw definitive conclusions. As for public health, increased consumption of magnesium-rich foods, such as whole grains, nuts, and green leafy vegetables, may bring considerable benefits in diabetes prevention, especially in those at high risk.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies provides further evidence in support of a significant inverse association between magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes, consistent with a dose-response relationship.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30771808).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

J.-Y.D. researched data, contributed to discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. P.X., K.H., and L.-Q.Q. contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. ; China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study Group. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1090–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Willett WC, Speizer FE. Diet and risk of clinical diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:1018–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belin RJ, He K. Magnesium physiology and pathogenic mechanisms that contribute to the development of the metabolic syndrome. Magnes Res 2007;20:107–129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balon TW, Jasman A, Scott S, Meehan WP, Rude RK, Nadler JL. Dietary magnesium prevents fructose-induced insulin insensitivity in rats. Hypertension 1994;23:1036–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balon TW, Gu JL, Tokuyama Y, Jasman AP, Nadler JL. Magnesium supplementation reduces development of diabetes in a rat model of spontaneous NIDDM. Am J Physiol 1995;269:E745–E752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao WH, Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, Mo JP, Watson RL, Brancati FL. Serum and dietary magnesium and the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2151–2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer KA, Kushi LH, Jacobs DR, Jr, Slavin J, Sellers TA, Folsom AR. Carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and incident type 2 diabetes in older women. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:921–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodge AM, English DR, O’Dea K, Giles GG. Glycemic index and dietary fiber and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2701–2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Ridaura R, Willett WC, Rimm EB, et al. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 2004;27:134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, Liu S. Dietary magnesium intake in relation to plasma insulin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2004;27:59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dam RM, Hu FB, Rosenberg L, Krishnan S, Palmer JR. Dietary calcium and magnesium, major food sources, and risk of type 2 diabetes in U.S. black women. Diabetes Care 2006;29:2238–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulze MB, Schulz M, Heidemann C, Schienkiewitz A, Hoffmann K, Boeing H. Fiber and magnesium intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:956–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villegas R, Gao YT, Dai Q, et al. Dietary calcium and magnesium intakes and the risk of type 2 diabetes: the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1059–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopping BN, Erber E, Grandinetti A, Verheus M, Kolonel LN, Maskarinec G. Dietary fiber, magnesium, and glycemic load alter risk of type 2 diabetes in a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii. J Nutr 2010;140:68–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DJ, Xun P, Liu K, et al. Magnesium intake in relation to systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and the incidence of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2604–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirii K, Iso H, Date C, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A; JACC Study Group. Magnesium intake and risk of self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese. J Am Coll Nutr 2010;29:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nanri A, Mizoue T, Noda M, et al. ; Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group. Magnesium intake and type II diabetes in Japanese men and women: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010;64:1244–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Intern Med 2007;262:208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 1994;17:961–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:481–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB, Dawson-Hughes B. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2017–2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1301–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–1101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racette SB, Evans EM, Weiss EP, Hagberg JM, Holloszy JO. Abdominal adiposity is a stronger predictor of insulin resistance than fitness among 50-95 year olds. Diabetes Care 2006;29:673–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon CY, Lokken RP, Hu FB, van Dam RM. Physical activity of moderate intensity and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2007;30:744–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007;298:2654–2664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suárez A, Pulido N, Casla A, Casanova B, Arrieta FJ, Rovira A. Impaired tyrosine-kinase activity of muscle insulin receptors from hypomagnesaemic rats. Diabetologia 1995;38:1262–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandeel FR, Balon E, Scott S, Nadler JL. Magnesium deficiency and glucose metabolism in rat adipocytes. Metabolism 1996;45:838–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, Manson JE, Liu S. Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled trials. Diabet Med 2006;23:1050–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerrero-Romero F, Tamez-Perez HE, González-González G, et al. Oral magnesium supplementation improves insulin sensitivity in non-diabetic subjects with insulin resistance. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Diabetes Metab 2004;30:253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chacko SA, Sul J, Song Y, et al. Magnesium supplementation, metabolic and inflammatory markers, and global genomic and proteomic profiling: a randomized, double-blind, controlled, crossover trial in overweight individuals. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:463–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mooren FC, Krüger K, Völker K, Golf SW, Wadepuhl M, Kraus A. Oral magnesium supplementation reduces insulin resistance in non-diabetic subjects - a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011;13:281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson SG. Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. BMJ 1994;309:1351–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart LA, Tierney JF. To IPD or not to IPD? Advantages and disadvantages of systematic reviews using individual patient data. Eval Health Prof 2002;25:76–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1887–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]