Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Insulin secretion is often diminished in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes. We examined whether chronic basal insulin treatment with insulin glargine improves glucose-induced insulin secretion.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Fourteen patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin monotherapy received an add-on therapy with insulin glargine over 8 weeks. Intravenous glucose tolerance tests (IVGTTs) were performed before and after the intervention, with and without previous adjustment of fasting glucose levels using a 3-h intravenous insulin infusion.

RESULTS

Fasting glycemia was lowered from 179.6 ± 7.5 to 117.6 ± 6.5 mg/dL (P < 0.001), and HbA1c levels declined from 8.4 ± 0.5 to 7.1 ± 0.2% (P = 0.0046). The final insulin dose was 59.3 ± 10.2 IU. Acute normalization of fasting glycemia by intravenous insulin reduced C-peptide levels during the IVGTT (P < 0.0001). In contrast, insulin and C-peptide responses to intravenous glucose administration were significantly greater after the glargine treatment period (P < 0.0001, respectively). Both first- and second-phase insulin secretion increased significantly after the glargine treatment period (P < 0.05, respectively). These improvements in insulin secretion were observed during both the experiments with and without acute adjustment of fasting glycemia.

CONCLUSIONS

Chronic supplementation of long-acting basal insulin improves glucose-induced insulin secretion in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes, whereas acute exogenous insulin administration reduces the β-cell response to glucose administration. These data provide a rationale for basal insulin treatment regiments to improve postprandial endogenous insulin secretion in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes.

Insulin secretion in response to glucose stimulation is often markedly diminished in patients with type 2 diabetes (1,2). This has been largely attributed to a deficit in β-cell mass ranging from ∼40 to 65% compared with nondiabetic individuals (3). However, the functional impairment in insulin secretion often exceeds the extent of the β-cell deficit (1), suggesting additional impairments in β-cell function. A number of functional abnormalities, including abnormal proinsulin processing or disturbances in the entero-insular axis have been suggested to contribute to the dysfunctional regulation of insulin release in patients with type 2 diabetes (4). In addition to these factors, there is good evidence for a reduction of glucose-induced insulin secretion with chronic hyperglycemia (5). Thus, when glucose-induced insulin secretion was determined in a large number of individuals presenting with different ranges of fasting glycemia, the early response was largely diminished at glucose levels >115 mg/dL (6). Furthermore, inducing chronic hyperglycemia in nondiabetic individuals by means of exogenous glucose infusion has led to a depletion of insulin secretion after ∼3 days (7), and insulin secretion from isolated human islets was found to be markedly diminished after chronic exposure to high glucose concentrations (8). On that basis, induction of β-cell rest by temporary inhibition of insulin exocytosis has been suggested as a therapeutic concept to restore glucose-induced insulin secretion (9). In line with such reasoning, temporary inhibition of insulin exocytosis using potassium-channel openers has normalized the subsequent glucose-induced insulin secretion in diabetic animals as well as in humans (10), and exogenous insulin supplementation has led to improvements in endogenous insulin secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes (11). Furthermore, a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion regimen in overtly hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes has led to marked improvements in glucose-induced insulin secretion, whereas the insulin response to glucagon stimulation was unchanged by the intervention (12). It is noteworthy that a large study using a transient period of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion or multiple daily insulin injections in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes has demonstrated persistent improvements in the acute insulin response to glucose even 1 year after the short-term intervention (13). However, because in most previous studies insulin secretion before and after the respective interventions was determined at different glucose levels, it is difficult to distinguish whether the observed improvements in insulin secretion were primarily the result of the chronic reduction in hyperglycemia or of the acute differences in glycemia at the time of the experiments. In addition, the effects of long-acting insulin analogs on endogenous insulin secretion have not yet been specifically examined.

Therefore, the current study was designed to examine 1) whether basal insulin treatment of hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes improves first- and second-phase insulin secretion in response to glucose, and if so, 2) whether this was attributable to the chronic improvements in glycemia or the acute differences in fasting glucose levels during the experiments.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study protocol

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of Ruhr University Bochum before the experiments (registration no. 3231-FF) as well as the German federal regulatory authorities (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte [BfArm]). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patients

Patients with type 2 diabetes (World Health Organization criteria) who presented with fasting glucose levels >126 mg/dL on metformin monotherapy were included. A total of 19 patients with type 2 diabetes were initially screened. Among those, 14 (12 male and 2 female) were eligible for the study. Their mean age was 55.7 ± 9.8 years, the weight was 105.3 ± 16.1 kg, and the BMI was 34.4 ± 5.4 kg/m2. The mean diabetes duration was 4.6 ± 3.0 years. Detailed characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and laboratory values of patients with type 2 diabetes before and after 8 weeks of basal insulin treatment

| Parameter (unit) | Before treatment | After treatment | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | 105.3 ± 16.1 | 106.4 ± 16.2 | 0.13 |

| Insulin units/day (IU) | — | 59.3 ± 38.0 | — |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 179.6 ± 28.0 | 117.6 ± 24.2 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.4 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 0.0046 |

| AST (units/L) | 43.6 ± 45.7 | 32.1 ± 20.2 | 0.21 |

| ALT (units/L) | 40.3 ± 28.8 | 32.1 ± 24.7 | 0.001 |

| GGT (units/L) | 57.1 ± 43.6 | 44.7 ± 9.4 | 0.013 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.94 ± 0.22 | 0.90 ± 0.19 | 0.26 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 206.6 ± 58.5 | 187.8 ± 49.3 | 0.01 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 42.0 ± 19.5 | 43.3 ± 14.9 | 0.98 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 119.5 ± 47.2 | 121.1 ± 47.1 | 0.99 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 338.4 ± 240.2 | 224.5 ± 147.8 | 0.004 |

Data are means ± SD. Statistics: paired Student t test. GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Study design

At a screening visit, blood was drawn from all participants in the fasting state for measurements of standard hematological and clinical chemistry parameters, and a general clinical examination was performed. Subjects with anemia (hemoglobin <12 g/dL), elevation in liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and γ-glutamyl transferase) to higher activities than double the respective normal value, or elevated creatinine concentrations (>1.5 mg/dL) were excluded. Body height and weight were determined and waist and hip circumference were measured to calculate BMI and the waist-to-hip ratio, respectively. Blood pressure was determined according to the Riva-Rocci method. If subjects met the inclusion criteria, they were studied on two occasions: 1) an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) after acute glucose normalization and 2) an IVGTT without acute glucose normalization.

Subsequently, all patients were assigned to a basal insulin regimen with the subcutaneous administration of insulin glargine at bedtime over 8 weeks. The respective insulin dose was estimated according to standard treatment recommendations and up-titrated according to a forced titration schedule (14), seeking a target fasting glucose level of <100 mg/dL. All patients were instructed by a specialized team of physicians and nurse instructors and encouraged to self-monitor their fasting blood glucose levels every morning. Patients were contacted at 2-day intervals via phone by the study physician to discuss the latest glucose measurements. If necessary, the respective daily insulin dose was up-titrated every 2 days to meet the desired fasting glucose levels. After the 8-week treatment period, the IVGTTs with and without acute glucose normalization were repeated.

The two experiments before and after the treatment period were carried out in randomized order on 2 subsequent days. Insulin glargine was withheld for 48 h preceding the tests, and metformin was paused on the morning of the experiments. By these means, the fasting glucose levels on the experimental days were typically higher than during the preceding treatment period.

Experimental procedures

All tests were performed in the morning after an overnight fast with subjects in a supine position throughout the experiments. Two forearm veins were punctured with a teflon cannula (Moskito 123, 18 gauge; Vygon, Aachen, Germany) and were kept open using 0.9% NaCl (for blood sampling and for glucose and insulin administration, respectively). Both ear lobes were made hyperemic using Finalgon (Nonivamid, 4 mg/g; Nicoboxil, 25 mg/g).

An intravenous glucose bolus (0.3 mg/kg body weight of a 50% glucose solution) was administered at t = 0 min, and venous blood samples were drawn at t = −5, 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min. In addition, capillary blood samples (∼20 μl) were collected for the immediate measurement of glucose (Glucocapil; Hitado Diagnostics, Delecke, Germany).

Acute glucose normalization protocol.

To examine the effects of acute versus chronic normalization of fasting glycemia, and to examine glucose-induced insulin secretion at comparable baseline glucose levels, an intravenous insulin infusion regimen was applied on 1 experimental day before and after the treatment period. The insulin infusion was varied as needed to reach a fasting plasma glucose concentration of 90–100 mg/dL within 3 h and to maintain this glucose concentration for the duration of the insulin infusion. After 180 min, the infusion of insulin was stopped 30 min before giving the intravenous glucose bolus. Subsequently, the glucose bolus was administered over 30 s.

Blood specimens

Venous blood was drawn into chilled tubes containing EDTA, aprotinin (Trasylol; 20,000 KIU/mL, 200 µL per 10 mL blood; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany), and specific dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor (valine-pyrrolidide, final concentration of 0.01 mmol/L; a gift from R.D. Carr, Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) and kept on ice. After centrifugation at 4°C, plasma for hormone analyses was kept frozen at −28°C.

Laboratory determinations

Insulin was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay from a Modular Analytics E 170 module on a Modular analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Cross-reactivity with human proinsulin was 0.05%. This assay has been shown not to cross-react with insulin glargine at concentrations from 30 to 1000 mU/L (also no cross-reactivity with insulin lispro and insulin aspart).

C-peptide was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay from a Modular Analytics E 170 module on a Modular analyzer. Cross-reactivity with human proinsulin was 32.5%.

Calculations and statistical analyses

Insulin secretion rates were calculated from C-peptide concentrations as previously described (15) using the software ISEC version 3.4a, supplied by R. Hovorka (City University, London, U.K.).

First-phase insulin response was assessed from the mean insulin secretion rates during the first 10 min after the glucose bolus subtracted by the basal secretion rates, and second-phase insulin secretion was determined as the mean insulin secretion rates from 10 to 120 min after glucose administration subtracted by basal levels.

Patient characteristics are presented as mean ± SD; results are reported as mean ± SEM. All statistical calculations were carried out using repeated-measures ANOVA using Statistica version 5.0 (Statsoft Europe, Hamburg, Germany). Values at single time points were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan`s post hoc test. A two-sided P value <0.05 was taken to indicate significant differences.

RESULTS

Fasting glucose concentrations were 179.6 ± 7.5 mg/dL before the insulin treatment and 117.6 ± 6.5 mg/dL after the 8-week basal insulin treatment period (P < 0.001), thus resulting in a mean treatment difference of 62.1 ± 6.9 mg/dL. HbA1c levels declined from 8.4 ± 0.5 to 7.1 ± 0.2% (P = 0.0046). The mean insulin dose at the end of the insulin treatment period was 59.3 ± 10.2 IU. Body weight did not change significantly during the 8-week study period (105.3 ± 4.3 vs. 106.4 ± 4.3 kg, respectively; P = 0.13). No minor or major hypoglycemic events occurred during the trial.

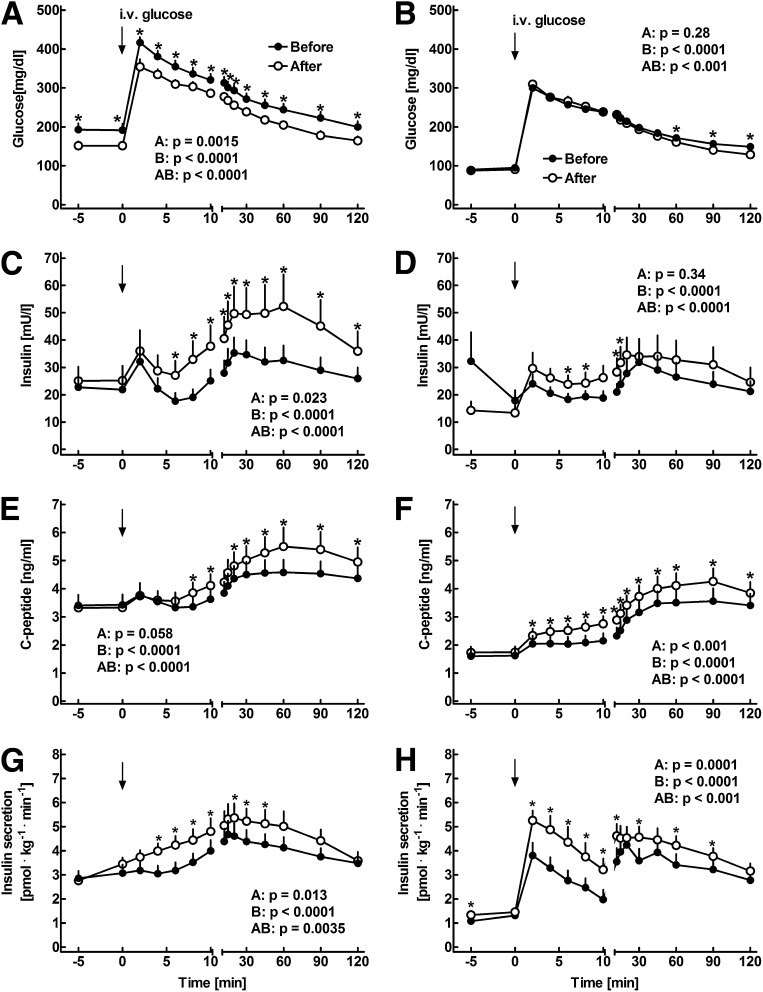

Acute normalization of fasting glucose concentrations by intravenous insulin infusion led to a significant reduction in C-peptide concentrations during the IVGTT compared with the experiments without prior glucose adjustment (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma concentrations of glucose (A and B), insulin (C and D), and C-peptide (E and F) as well as insulin secretion rates (G and H) in 14 patients with type 2 diabetes before (filled symbols) and after (open symbols) 8 weeks of insulin glargine treatment. Intravenous glucose was administered at 0 min. The experiments were performed without (A, C, E, and G) and with (B, D, F, and H) prior adjustment of fasting glycemia using a 3-h intravenous insulin infusion. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistics were carried out using paired repeated-measures ANOVA and denote (A) differences between the experiments, (B) differences over the time course, and (AB) differences due to the interaction of experiment and time. Asterisks indicate significant differences at individual time points (P < 0.05).

During the experiments without prior adjustment of glucose concentrations, plasma glucose levels before the glargine treatment were higher at baseline and after intravenous glucose administration compared with the post-treatment values (P < 0.001). There were no differences in fasting insulin or C-peptide concentrations between the experiments before and after glargine treatment (Fig. 1). Intravenous glucose administration led to an increase in insulin and C-peptide concentrations (P < 0.05). After 8 weeks of glargine treatment, insulin and C-peptide concentrations were significantly higher between 6 and 120 min and between 8 and 120 min after glucose administration, respectively (P < 0.0001). In addition, insulin secretion rates were significantly higher after the glargine treatment period (P = 0.0035).

During the experiments with prior adjustment of glycemia, fasting glucose concentrations were similar after the acute insulin infusion (Fig. 1). The total amount of intravenous insulin required to reach normoglycemia was 17.9 ± 3.6 IU before and 10.6 ± 1.7 IU after the intervention (P = 0.0041). Intravenous glucose administration led to an immediate rise in glycemia, with slightly higher glucose levels between t = 60 and 120 min in the experiments before glargine treatment (P < 0.05). Insulin and C-peptide levels were not significantly different before intravenous glucose administration, but the postchallenge concentrations were higher in the experiments after glargine treatment (P < 0.0001, respectively). Calculation of the insulin secretion rates identified a biphasic insulin release pattern both before and after the glargine treatment (Fig. 1). However, the insulin secretion rates were significantly higher after the treatment period during the early and late phase of insulin secretion (P < 0.001).

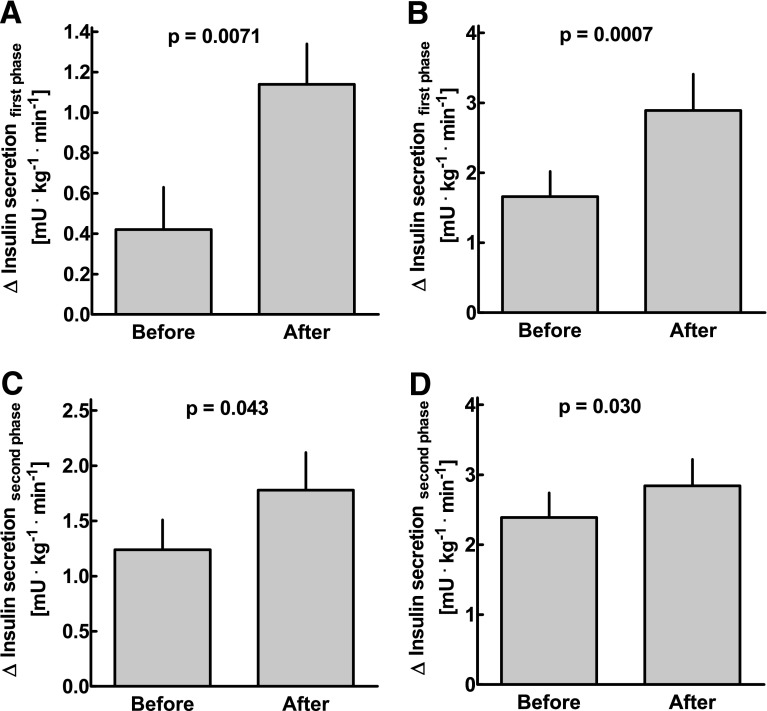

In the experiments without acute glucose adjustment, first-phase insulin secretion was 0.42 ± 0.21 pmol ⋅ kg−1 ⋅ min−1 before and 1.14 ± 0.20 pmol ⋅ kg−1 ⋅ min−1 after glargine treatment (P = 0.0071; Fig. 2), and second-phase insulin secretion was 1.24 ± 0.27 vs. 1.78 ± 0.34 pmol ⋅ kg−1 ⋅ min−1 (P = 0.043). The respective changes in the experiments with acute glucose adjustment were 1.66 ± 0.36 vs. 2.89 ± 0.52 pmol ⋅ kg−1 ⋅ min−1 for the changes in first-phase secretion (P < 0.001) and 2.39 ± 0.39 vs. 2.84 ± 0.38 pmol ⋅ kg−1 ⋅ min−1 for the changes in second-phase secretion (P = 0.030; Fig. 2). There was no significant association between the amount of intravenous insulin required to achieve normoglycemia on the day of the experiments and either first- or second-phase insulin secretion after intravenous glucose administration (r2 = 0.14, P = 0.052, and r2 = 0.11, P = 0.085, respectively; details not shown).

Figure 2.

First-phase insulin secretion (A and B; insulin secretion rates at t = 0–10 min minus basal levels) and second-phase insulin secretion (C and D; insulin secretion rates from t = 10 to 120 min minus basal levels) in response to intravenous glucose administration in 14 patients with type 2 diabetes before and after 8 weeks of insulin glargine treatment. The experiments were performed without (A and C) and with (B and D) prior adjustment of fasting glycemia using a 3-h intravenous insulin infusion. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistics were carried out using paired t tests.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study was designed to examine the effects of chronic versus acute insulin treatment on endogenous β-cell function in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes. We report that chronic administration of basal insulin over 8 weeks results in improvements in first- and second-phase insulin secretion, even under conditions of identical fasting glucose levels. In contrast, acute normalization of fasting glycemia by a 3-h intravenous insulin infusion reduced C-peptide levels during an IVGTT.

The effects of exogenous insulin treatment on endogenous insulin secretion have previously been examined under various conditions (11,16). However, in most of these studies, continuous intravenous or subcutanoues insulin administration regiments have been applied, and the treatment duration was typically rather short. Furthermore, in the current study, glucose-induced insulin secretion has for the first time been examined with and without prior adjustment of fasting glycemia. By these means, it was possible to examine the effects of chronic insulin replacement on β-cell function independent of differences in baseline glucose levels. It is arguable that an oral glucose challenge would have represented a more physiological challenge than intravenous glucose administration. However, insulin secretion after oral glucose ingestion is also largely affected by changes in gastric emptying, intestinal glucose absorption, and incretin hormone secretion. Therefore, in the current study, intravenous glucose administration was chosen.

It is noteworthy that acute normalization of first- and second-phase insulin secretion has previously been reported after an overnight infusion of the incretin mimetic exenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (17). The current study now demonstrates that improvements in insulin secretion can also be elicited with a basal insulin treatment regimen, even in the absence of a direct insulin secretagog.

The present findings are consistent with the concept that chronic hyperglycemia leads to a functional reduction of insulin secretion via depletion of insulin secretory granules. Indeed, a number of studies have demonstrated a gradual reduction of insulin secretion with increasing fasting glucose levels (5,6), and mechanistic studies have suggested a replenishment of the insulin granule stores, leading to an improvement of glucose-induced insulin secretion after reduction of hyperglycemia (9). Consistent with this, exposure of isolated human islets to chronic hyperglycemia has led to a reduction in the mean islet insulin content and a loss of first-phase insulin secretion, and these defects could be restored by temporarily inhibiting insulin exocytosis using a potassium channel opener (8). In a similar fashion, overnight inhibition of insulin secretion using somatostatin has caused marked improvements in subsequent insulin secretory responses to glucose stimulation in patients with type 2 diabetes (18). The present as well as some previous studies extend this concept by demonstrating that a functional β-cell rest cannot only be induced by direct inhibition of insulin exocytosis but also by reducing the secretory demand on the β cells through chronic insulin supplementation. Another important mechanism that might have contributed to the improvements in insulin secretion in this study is a reduction of gluco- and potentially lipotoxicity. Along these lines, a number of studies have provided compelling evidence that chronically elevated concentrations of glucose or free fatty acids can impair β-cell function through the generation of reactive oxygen species (19). In turn, exogenous administration of antioxidant drugs and overexpression of antioxidant enzymes in β cells have led to significant improvements in β-cell function (20,21). Therefore, it appears likely that the insulin treatment intervention in this has also reduced the detrimental effect of gluco- and lipotoxicity on β-cell function.

The improvements in endogenous insulin secretion after 8 weeks of glargine therapy provide a rationale for the use of basal insulin treatment regiments in patients with type 2 diabetes. Thus, whereas exogenously administered insulin acts primarily at the peripheral tissue level, the improvements in endogenous insulin release increase postprandial insulin secretion. Furthermore, because endogenous insulin is secreted directly from the islets into the portal venous circulation, the improvements in β-cell function are likely to result in additional improvements in α-cell function and hepatic glucose production (22). In line with such reasoning, Linn et al. (23) have recently demonstrated reductions in glucagon secretion as well as hepatic glucose release after a single dose administration of two different basal insulins at bedtime. These findings may explain why basal insulin treatment regimens often lower not only fasting but also postprandial glycemia.

The current study may also be interpreted in support of the postulate that the impairments in glucose-induced insulin secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes result from a combination of defects in β-cell mass and function. In fact, it is very unlikely that β-cell mass changes significantly over an 8-week study period, suggesting that the abnormalities in glucose-induced insulin release are at least partly attributable to the detrimental effects of chronic hyperglycemia on β-cell function.

Even though a forced insulin titration regimen was used in this study, the majority of patients failed to achieve the desired fasting glucose concentration range of <100 mg/dL. This might be partly explained by the large day-by-day fluctuations in fasting glycemia, partly caused by the lack of accuracy of finger-stick glucose measurements, which have prevented further up-titration of the insulin dose in a large number of patients. Thus, all 14 patients had reached fasting glucose levels of 100 mg/dL or less at least once during the insulin treatment period, but only one patient presented with glucose levels within the target range at the final day of the insulin treatment period. Furthermore, the presently examined group of patients with type 2 diabetes was rather obese and presumably insulin-resistant. As a consequence, a mean insulin dose of 59 IU per day was necessary to reduce fasting glycemia from 180 to 118 mg/dL. However, the failure to completely normalize fasting hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes appears to be consistent with both clinical practice and previous clinical studies (14) and provides a rationale for adding complimentary treatment options, such as short-acting insulin (24) or incretin-based therapies (25), if normoglycemia cannot be achieved with basal insulin alone. The improvement in β-cell function through the normalization of fasting hyperglycemia might particularly favor the combination of basal insulin with glucagon-like peptide-1–based drugs, which act by glucose dependently activating endogenous insulin release.

In conclusion, chronic supplementation of long-acting basal insulin improves glucose-induced endogenous insulin secretion in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes, whereas acute exogenous insulin administration lowers the β-cell response to glucose administration. These data provide a rationale for basal insulin treatment regiments in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from sanofi-aventis. The preparation of the article was independent of the company. J.J.M. and M.A.N. have received advisory board fees and speaker honoraria from sanofi-aventis. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

C.P. researched data and contributed to the discussion. N.S. researched data and contributed to the discussion. B.A.M. contributed to the data analysis and discussion. W.E.S. contributed to the discussion. M.A.N. contributed to the study design and data analysis and edited the manuscript. J.J.M. designed the study, contributed to data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

The excellent technical assistance of Birgit Baller, Mechthild Schweinsberg, and Kirsten Mros (Department of Medicine, St. Josef Hospital) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are indebted to Tim Heise and Christoph Kapitza (Profil Institute for Metabolic Research, Neuss, Germany) for their help with protocol preparation and patient recruitment.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT01249677, clinicaltrials.gov.

References

- 1.Pfeifer MA, Halter JB, Porte D, Jr. Insulin secretion in diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 1981;70:579–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward WK, Bolgiano DC, McKnight B, Halter JB, Porte D, Jr. Diminished B cell secretory capacity in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1984;74:1318–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003;52:102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull RL, Westermark GT, Westermark P, Kahn SE. Islet amyloid: a critical entity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:3629–3643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godsland IF, Jeffs JA, Johnston DG. Loss of beta cell function as fasting glucose increases in the non-diabetic range. Diabetologia 2004;47:1157–1166 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Brunzell JD, Robertson RP, Lerner RL, et al. Relationships between fasting plasma glucose levels and insulin secretion during intravenous glucose tolerance tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976;42:222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boden G, Ruiz J, Kim CJ, Chen X. Effects of prolonged glucose infusion on insulin secretion, clearance, and action in normal subjects. Am J Physiol 1996;270:E251–E258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritzel RA, Hansen JB, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Induction of beta-cell rest by a Kir6.2/SUR1-selective K(ATP)-channel opener preserves beta-cell insulin stores and insulin secretion in human islets cultured at high (11 mM) glucose. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:795–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown RJ, Rother KI. Effects of beta-cell rest on beta-cell function: a review of clinical and preclinical data. Pediatr Diabetes 2008;9:14–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Carr RD, Brand CL, Bodvarsdottir TB, Hansen JB, Sturis J. NN414, a SUR1/Kir6.2-selective potassium channel opener, reduces blood glucose and improves glucose tolerance in the VDF Zucker rat. Diabetes 2003;52:2513–2518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cusi K, Cunningham GR, Comstock JP. Safety and efficacy of normalizing fasting glucose with bedtime NPH insulin alone in NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1995;18:843–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Griffin J, Hamman RF, Kolterman OG. The effect of insulin treatment on insulin secretion and insulin action in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1985;34:222–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng J, Li Y, Xu W, et al. Effect of intensive insulin therapy on beta-cell function and glycaemic control in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a multicentre randomised parallel-group trial. Lancet 2008;371:1753–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003;26:3080–3086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hovorka R, Soons PA, Young MA. ISEC: a program to calculate insulin secretion. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1996;50:253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner RC, McCarthy ST, Holman RR, Harris E. Beta-cell function improved by supplementing basal insulin secretion in mild diabetes. BMJ 1976;1:1252–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehse F, Trautmann M, Holst JJ, et al. Exenatide augments first- and second-phase insulin secretion in response to intravenous glucose in subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:5991–5997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laedtke T, Kjems L, Pørksen N, et al. Overnight inhibition of insulin secretion restores pulsatility and proinsulin/insulin ratio in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2000;279:E520–E528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson RP, Harmon J, Tran PO, Poitout V. Beta-cell glucose toxicity, lipotoxicity, and chronic oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2004;53(Suppl. 1):S119–S124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho E, Chen G, Bray TM. Supplementation of N-acetylcysteine inhibits NFkappaB activation and protects against alloxan-induced diabetes in CD-1 mice. FASEB J 1999;13:1845–1854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubisch HM, Wang J, Bray TM, Phillips JP. Targeted overexpression of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase protects pancreatic beta-cells against oxidative stress. Diabetes 1997;46:1563–1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier JJ, Kjems LL, Veldhuis JD, Lefèbvre P, Butler PC. Postprandial suppression of glucagon secretion depends on intact pulsatile insulin secretion: further evidence for the intraislet insulin hypothesis. Diabetes 2006;55:1051–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linn T, Fischer B, Soydan N, Eckhard M, Ehl J, Kunz C, Bretzel RG. Nocturnal glucose metabolism after bedtime injection of insulin glargine or neutral protamine hagedorn insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:3839–3846 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lankisch MR, Ferlinz KC, Leahy JL, Scherbaum WA; Orals Plus Apidra and LANTUS (OPAL) study group. Introducing a simplified approach to insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a comparison of two single-dose regimens of insulin glulisine plus insulin glargine and oral antidiabetic drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10:1178–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnolds S, Dellweg S, Clair J, et al. Further improvement in postprandial glucose control with addition of exenatide or sitagliptin to combination therapy with insulin glargine and metformin: a proof-of-concept study. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1509–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]