Abstract

Background:

An important requirement during functional endoscopic sinus surgery is to maintain a clear operative field to improve visualization during surgery and to minimize complications.

Materials and Methods:

We compared total intravenous anesthesia using propofol with inhalational anesthesia using isoflurane for controlled hypotension in functional endoscopic sinus surgery. It was a prospective study in a tertiary hospital in India. Forty ASA physical status I and II adult patients (16–60 years) were randomly allocated to one of two parallel groups (isoflurane group, n = 20; propofol group, n = 20). The primary outcome was to know whether total intravenous anesthesia using propofol was superior to inhalational anesthesia using isoflurane for controlled hypotension. The secondary outcomes measured were intraoperative blood loss, duration of surgery, surgeon's opinion regarding the surgical field and the incidence of complications.

Results:

The mean (±SD) time to achieve the target mean blood pressure was 18 (±8) minutes in the isoflurane group and 16 (±7) minutes in the propofol group (P = 0.66). There was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.402) between these two groups in terms of intraoperative blood loss and operative field conditions (P = 0.34).

Conclusions:

Controlled hypotension can be achieved equally and effectively with both propofol and isoflurane. Total intravenous anesthesia using propofol offers no significant advantage over isoflurane-based anesthetic technique in terms of operative conditions and blood loss.

Keywords: Anesthetic techniques, hypotensive, isoflurane, otolaryngological surgeries, propofol

Introduction

The aim of functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is to restore the drainage and aeration of the paranasal sinuses, while maintaining the natural mucociliary clearance mechanism and seeking to preserve the normal anatomic structures.[1,2] However, this surgery can lead to complications such as orbital cellulitis, rhino-oral fistulas and damage to the optic nerve.[2–4] It is important to have a clear surgical field to minimize the complications. General anesthesia is often preferred over topical anesthesia because of the discomfort, and because incomplete block may be associated with topical anesthesia. Moreover, general anesthesia allows achieving hypotensive anesthesia.[4] Controlled hypotension is required in FESS procedures for better visualization and to minimize operative time and blood loss. Various agents like beta-blockers, alpha and beta blockers, alpha agonists, vasodilators, magnesium sulfate have been used to achieve controlled hypotension.[5,6] Isoflurane-based inhalational anesthetic technique for achieving controlled hypotension has gained wide popularity. Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) using propofol and remifentanil is a common practice in Western countries. Remifentanil is not freely available in India. This study was designed to evaluate TIVA with propofol and fentanyl and to determine whether controlled hypotension and better operative conditions can be achieved when compared to conventional isoflurane-based inhalational anesthetic technique.

Materials and Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional research and ethics committee and patients gave written informed consent. Sample size was calculated by a statistician as 20 in each group, based on previous studies to achieve a power of 80% and an alpha error of 0.05. Forty patients admitted during the one-year period to a tertiary care teaching hospital in India, belonging to ASA physical status I, aged 16–60 years, undergoing FESS were randomly allocated as per the computer-generated simple randomization code to one of the two parallel groups (isoflurane group, n = 20; propofol group, n = 20). Patients with bleeding disorders, major hepatic, renal or cardiovascular dysfunction, recurrent endoscopic sinus surgeries and anticoagulation therapy were excluded. The primary outcome was to know whether TIVA using propofol was superior to inhalational anesthesia using isoflurane for controlled hypotension. The secondary outcomes measured were intraoperative blood loss, duration of surgery, surgeon's opinion regarding the surgical field and the incidence of complications.

The allocation sequence was generated by the statistician. Allocation concealment was ensured with the use of sealed envelopes. The principal investigator enrolled the patients and following recruitment, the allocation was revealed in the operating room to the anesthesiologist anesthetizing the patients. Double blinding was not possible because of the nature of the study. The anesthesiologist was not blinded to the study drug but the anesthesiologist assessing the blood loss was blinded to the study drug.

The study patients were kept fasted as per the standard guidelines and premedicated with oral diazepam 0.2 mg kg–1 one hour prior to the induction of anesthesia. On arrival to the operating room, an intravenous (IV) line was sited and monitoring that included pulse oximetry (SpO2), noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP), electrocardiogram (ECG), end tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) and end tidal isoflurane agent analyzer was established. Neuromuscular blockade was monitored with a nerve stimulator.

Heart rate with ST segment analysis, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded before induction of anesthesia. After preoxygenation, induction of anesthesia was done with midazolam (2 mg), fentanyl (2 μg kg–1) and propofol (2 mg kg–1) IV. After ensuring adequate ventilation, vecuronium (0.1 mg kg–1) was administered via a fast-flowing IV infusion over five seconds. Orotracheal intubation was performed and the lungs were ventilated. Oropharynx was packed with a saline-soaked throat pack. An infusion of fentanyl was started at the rate of 2 μg kg–1h–1 following intubation in both groups.

Group 1 (Inhalational anesthesia)

Induction of anesthesia was done and maintained with 50% oxygen in air, and isoflurane. The concentration of isoflurane was adjusted using agent analyzer according to the patient's response and to achieve a mean arterial pressure between 60 and 70 mmHg. However, it was decided not to exceed the end tidal concentration of isoflurane above 2%.

Group 2 (TIVA)

Induction of anesthesia was done and maintained with 50% oxygen in air, propofol infusion started at 12 mg kg–1 h–1 for 10 min following intubation, then 10 mg kg–1 h–1 for next 10 min and continued at 8 mg kg–1 h–1. The infusion rate was increased according to the patient's response and to achieve a mean arterial pressure between 60 and 70 mmHg. However, it was decided not to exceed the maximal rate of propofol infusion above 12 mg kg–1 h–1.

During the perioperative period, both groups received IV normal saline at 4 ml kg–1 h–1. Neuromuscular blockade was achieved with an intermittent boluses of vecuronium adjusted to provide complete depression of the first twitch after TOF stimulation. Normothermia was maintained during the whole procedure. The volume of blood which was sucked and collected in the bottle was measured to assess the amount of blood loss. The second anesthesiologist who was not involved in the study made visual assessment of blood-soaked gauze pieces used during the surgery. This was added to the amount of blood loss. The infusion of fentanyl was stopped 30 min before the completion of the surgical procedure in all the patients. Ondansetron 4 mg IV was given at the end of the surgery. The throat pack was removed at the end of the endoscopic procedure. The residual neuromuscular blockade was reversed with 0.05 mg kg–1 of neostigmine and 0.02 mg kg–1 atropine IV.

Patients were followed up and monitored for pain, sedation score, nausea and vomiting in the post-operative period for 48 h. For evaluation of the visibility of the operative field during surgery, the quality scale proposed by Fromm and Boezaart[4] was used. The operative field conditions were assessed by the same operating surgeon as:

Grade 0: No bleeding.

Grade 1: Slight bleeding – No suctioning of blood required.

Grade 2: Slight bleeding – Occasional suctioning required. Surgical field not threatened.

Grade 3: Slight bleeding – Frequent suctioning required. Bleeding threatens surgical field a few seconds after suction is removed.

Grade 4: Moderate bleeding – Frequent suctioning required. Bleeding threatens surgical field directly after suction is removed.

Grade 5: Severe bleeding – Constant suctioning required. Bleeding appears faster than can be removed by suction. Surgical field severely threatened and surgery impossible.

The data were entered into a Microsoft Excel Computer Programme. Data were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 13.0). Descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies, median and means, standard deviations were calculated. The variations in the HR, MAP within each group were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA and compared between the groups using Student's t test. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

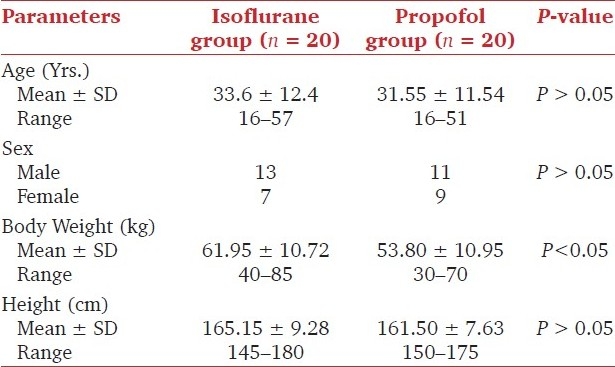

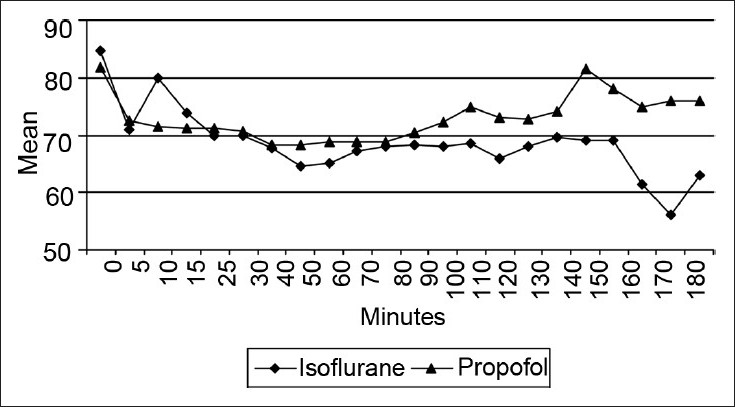

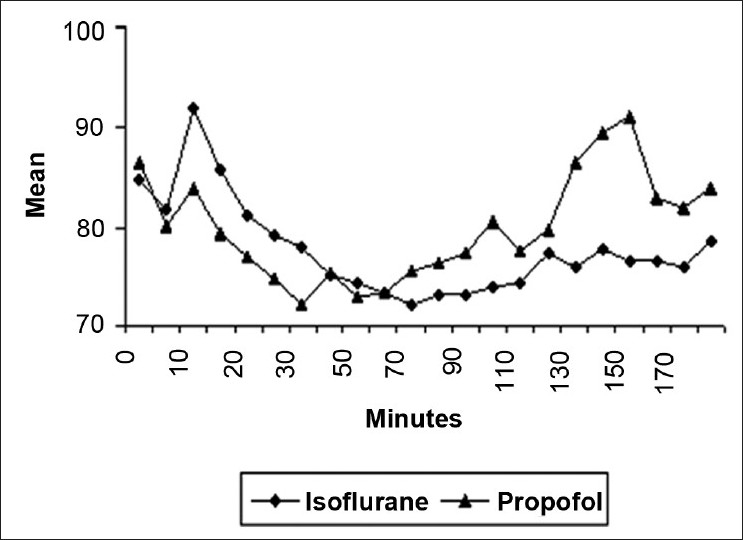

Forty ASA physical status I and II patients undergoing FESS were studied (isoflurane group, n = 20; propofol group, n = 20). Patients of both groups were comparable in relation to age and height but varied in their weight [61.95(±10.72) vs. 53.80(±10.95), P = 0.023] [Table 1]. The mean (±SD) time to achieve the target blood pressure in isoflurane groups was 18(±8) minutes and 16(±7) minutes in the propofol group. There was no statistical difference (P = 0.66) between the two groups with regard to median time in achieving target blood pressure (18–28) min [Figure 1]. When compared to the baseline, there was no significant difference between the two groups with regards to heart rate at different time intervals [Figure 2]. There was no significant difference between these two groups in terms of intraoperative blood loss [Table 2].

Table 1.

Demographic data

Figure 1.

Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) in the two groups at different time intervals

Figure 2.

Mean heart rate (beats min-1) in the two groups at different time intervals

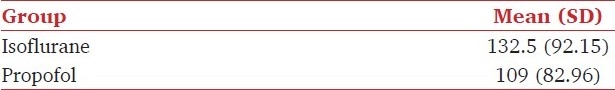

Table 2.

Intraoperative blood loss (ml) in the two groups

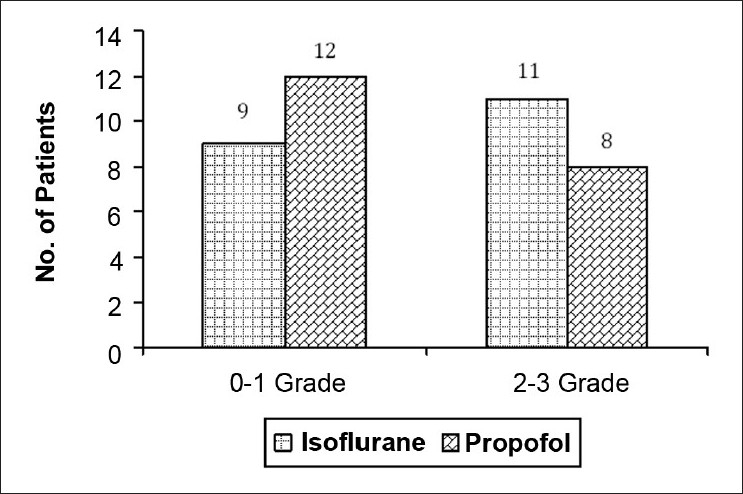

The operative field conditions assessed by the same surgeon were grade 3 and less in both the groups (P = 0.34) [Figure 3]. The duration of surgery was less with propofol group when compared to isoflurane group [131(±36) vs. 98(±41) min, P = 0.01]. The mean fentanyl requirement was greater with isoflurane group [4.68 (±1) μg/kg vs. 3.94(±0.96) μg/kg, P = 0.026] when compared to propofol group. There was no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of sedation score, pain, nausea, vomiting and hospital-stay. None of them had intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Figure 3.

Operative field conditions based on Fromm and Boezaart Scale in the two groups

Discussion

Isoflurane-based inhalational anesthetic technique can be practiced wherever a general anesthetic is given. However, there is always a need to explore newer techniques and drugs to try and achieve better results and conditions for surgeries like FESS. One such technique that is gaining tremendous popularity for controlled hypotension is TIVA with propofol and remifentanil. It is not freely available and the cost of remifentanil in India would also be prohibitive for routine use. This study was designed to evaluate TIVA with propofol and fentanyl and to determine whether better results and operative conditions can be achieved when compared to conventional isoflurane-based inhalational anesthetic technique for controlled hypotension.

The goal of a target mean blood pressure of 60-70 mmHg was achieved in the groups in a mean time of 18(±8) min in isoflurane group and 16(±7) min in the propofol group and median time of 10 min in both the groups. Both isoflurane- and propofol-based techniques were equally capable of producing controlled hypotension. The highest concentration used in isoflurane group to achieve target blood pressure was an inspired concentration of 2.5% and end tidal concentration of 2%.

In a study by Tirelli et al., mean arterial pressure of 60–70 mmHg was aimed for in FESS. A concentration of 1–2% of isoflurane was used in the isoflurane group for the maintenance, which is almost similar to our study. In the TIVA group, hypotensive anesthesia was achieved using propofol and remifentanil.[7] Rate of propofol used was 35–45 ml hr–1 whereas in our study, we used the infusion rate based on the patient's body weight and hemodynamic response. Other factors which influence the propofol dosage requirement include age, weight, preexisting medical condition, type of surgical procedure and concomitant medical therapy.[8] In our study, maintenance of target blood pressure within the 60–70 mmHg range was more consistent with isoflurane group when compared to the propofol group and this was particularly appreciable when observing the graph [Figure 1], whereas there were several departures away from the target zone in the propofol group.

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of heart rate measured at different time intervals. The absence of tachycardia suggests that both the groups experienced adequate depth of anesthesia and analgesia because of the concomitant use of fentanyl. None of the patients had intraoperative awareness which was enquired in postoperative follow-up. There was no significant difference in the intraoperative blood loss between two groups. The reduced blood loss in both the groups reflects effective controlled hypotension by both the techniques.

Nair et al. described that patients on beta-blockers undergoing FESS had better surgical field with the heart rate less than 60 beats min–1.[9] We achieved acceptable surgical conditions even though the heart rate in both the groups of our study was more than 60 beats min–1. Mandal observed less bleeding with hypotensive anesthesia using isoflurane in FESS as compared to normotensive anesthesia provided by isoflurane. There were no postoperative complications due to intraoperative hypotension.[10]

Elsharnouby and Elsharnouby used magnesium sulfate for hypotensive anesthesia and observed a significant reduction in surgical time, blood loss, mean arterial blood pressure (P < 0.005) and heart rate (P < 0.005) in the magnesium group when compared to placebo group.[11] In our study, the operative field assessed by Fromme-Boezzart scale was similar in both the groups. All patients in both the groups belonged to grade 3 and below, which denotes highly acceptable surgical field as far as the surgeon was concerned. However, in the study by Tirelli, surgical field grading was better with propofol group when compared to isoflurane group. They also postulated that increased oozing in the isoflurane group could be due to the vasodilating property of isoflurane.[7] In our study, the mean fentanyl requirement was greater with isoflurane group when compared to the propofol group. This could be due to the longer surgery time in the isoflurane group when compared to propofol group. None of the patients in two groups had postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). This could be due to prophylactic administration of ondansetron and avoidance of nitrous oxide in both the groups. The use of propofol can be associated with less PONV or decreased requirements for antiemetic medication.[12] Antagonism of the dopamine D2 receptor by propofol has recently been suggested as a possible mechanism for this effect.[13] Visser et al. observed that TIVA using propofol results in a clinically relevant reduction of PONV compared with isoflurane-nitrous oxide anesthesia.[14] If this study had eliminated nitrous oxide in the inhalational group, as we did, they might have found lesser incidence of PONV in the inhalational group too.

Conclusions

Controlled hypotension can be achieved equally and effectively by both isoflurane-based inhalational anesthetic technique and TIVA using propofol and fentanyl. TIVA using propofol offers no significant advantage over isoflurane-based inhalational anesthetic technique in terms of operative conditions and blood loss.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the fluid research committee, Christian Medical College, Vellore for funding the study and the otolaryngological surgeons for their immense co-operation during the performance of study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Fluid Research Committee, Christian Medical College, Vellore

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Stammberger H, Posawetz W. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery.Concept, indications and results of the Messerklinger technique. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1990;247:63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00183169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stankiewicz JA. Complications of endoscopic intranasal ethmoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:1270–3. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198711000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maniglia AJ. Fatal and other major complications of endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:349–54. doi: 10.1002/lary.1991.101.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boezaart AP, van der Merwe J, Coetzee A. Comparison of sodium nitroprusside- and esmolol-induced controlled hypotension for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:373–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03015479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryu JH, Sohn IS, Do SH. Controlled hypotension for middle ear surgery: A comparison between remifentanil and magnesium sulphate. Br J Anaesth. 2009;229:1–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray M, Bhattacharjee DP, Hajra B, Pal R, Chatterjee N. Effect of clonidine and magnesium sulphate on anaesthetic consumption, haemodynamics and postoperative recovery: A comparative study. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:137–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.63659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tirelli G, Bigarini S, Russolo M, Lucangelo U, Gullo A. Total intravenous anaesthesia in endoscopic sinus-nasal surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004;24:137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith I, White PF, Nathanson M, Gouldson R. Propofol: An update on its clinical use. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:1005–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair S, Collins M, Hung P, Rees G, Close D, Wormald PJ. The effect of beta-blocker premedication on the surgical field during endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1042–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200406000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandal P. Isoflurane anesthesia for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsharnouby NM, Elsharnouby MM. Magnesium sulphate as a technique of hypotensive anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:727–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price ML, Walmsley A, Swaine C, Ponte J. Comparison of total intravenous anaesthetic technique using a propofol infusion, with an inhalational technique using enflurane for day case surgery. Anaesthesia. 1998;43:84–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb09081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiFlorio T. Is propofol a dopamine antagonist? Anesth Analg. 1993;77:200–1. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199307000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visser K, Hassink EA, Bonsel GJ, Moen J, Kalkman CJ. Randomized controlled trial of total intravenous anesthesia with propofol versus inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane-nitrous oxide: Postoperative nausea with vomiting and economic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:616–26. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]