Abstract

Aerobic respiration in bacteria, Archaea, and mitochondria is performed by oxygen reductase members of the heme-copper oxidoreductase superfamily. These enzymes are redox-driven proton pumps which conserve part of the free energy released from oxygen reduction to generate a proton motive force. The oxygen reductases can be divided into three main families based on evolutionary and structural analyses (A-, B- and C-families), with the B- and C-families evolving after the A-family. The A-family utilizes two proton input channels to transfer protons for pumping and chemistry, whereas the B- and C-families require only one. Generally, the B- and C-families also have higher apparent oxygen affinities than the A-family. Here we use whole cell proton pumping measurements to demonstrate differential proton pumping efficiencies between representatives of the A-, B-, and C-oxygen reductase families. The A-family has a coupling stoichiometry of 1 H+/e-, whereas the B- and C-families have coupling stoichiometries of 0.5 H+/e-. The differential proton pumping stoichiometries, along with differences in the structures of the proton-conducting channels, place critical constraints on models of the mechanism of proton pumping. Most significantly, it is proposed that the adaptation of aerobic respiration to low oxygen environments resulted in a concomitant reduction in energy conservation efficiency, with important physiological and ecological consequences.

Keywords: cytochrome oxidase, evolution

Aerobic respiration is the most exergonic metabolic process known. It plays a central role in the biogeochemical cycles of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur and is important in determining the structure of many microbial ecosystems (1). Many bacteria and Archaea, along with the vast majority of eukaryotes, are able to perform aerobic respiration, coupling the reduction of O2 to the conservation of free energy in a proton electrochemical gradient (2, 3). There are currently two known groups of respiratory oxygen reductases, (i) the bd family of oxygen reductases and (ii) oxygen reductase members of the heme-copper oxidoreductase superfamily. These enzymes utilize two distinct mechanisms to generate and maintain a steady-state proton motive force: charge separation and proton pumping (4).

Charge separation by “vectorial chemistry” is a common mechanism that contributes to the transmembrane electric potential (ΔΨ) in many bioenergetic redox processes (5). Both the bd and heme-copper oxygen reductases utilize electrons from the periplasm and protons from the cytoplasm to catalyze the reduction of O2 to two H2O, assuring that the chemistry of oxygen reduction is coupled to charge separation across the membrane (6). For each electron transferred to the active site for chemistry, one charge crosses the membrane.

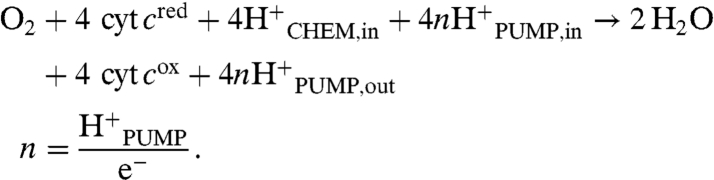

In proton pumping, protons are taken from the bacterial cytoplasm, actively transported across the membrane and released on the outside. The heme-copper oxygen reductases are the only known oxygen reductases that pump protons. The stoichiometry of proton pumping (n) is one measure of the efficiency of energy conservation, where n is the number of protons pumped per electron consumed during the reaction (four electrons per O2). The overall chemical reaction catalyzed by the cytochrome c oxidases (i.e., oxygen reductases utilizing cytochrome c as reductant) can be written as

|

The heme-copper oxygen reductases have been classified into three major families (A-, B-, and C-families) based on structural and phylogenetic analysis (7, 8). Phylogenetic analysis indicates that the A-family is the most ancient and that both the B- and C-families evolved later. The oxygen reductases from the B- and C-families have higher apparent oxygen affinities than the A-family and are physiologically expressed under low O2 or microaerobic conditions, suggesting that they are adapted to function in these environments.

The heme-copper oxygen reductase families all share a homologous core subunit (subunit I) which contains all of the components required for oxygen reduction and proton pumping. All of the families appear to utilize a similar reaction mechanism for oxygen reduction, which is catalyzed at an active site that contains a five-coordinate high spin heme, a copper ion (CuB), and a unique cross-linked tyrosine-histidine cofactor (9).

The protons required for active-site chemistry and proton pumping are delivered by proton conducting channels. These channels contain hydrophilic amino acid residues, which, with internal water molecules, provide continuous hydrogen bond pathways that facilitate rapid proton diffusion from the bulk solution (e.g., bacterial cytoplasm) to the active site and proton loading site. The residues forming the proton channels are conserved within each family but vary between the different families. The A-family oxygen reductases contain two proton channels, the D- and K-channels. The K-channel transports two protons to the active site for chemistry, whereas the D-channel transports the remaining two chemical protons along with all four of the pumped protons (per O2). The B- and C-family oxygen reductases each contain an analogue of the K-channel, located in the same structural position as in the A-family (10, 11). Remarkably, the B- and C-family oxygen reductases are missing the D-channel and require only one proton input channel, the K-channel analogue, to transfer all of the protons required for both chemistry and proton pumping. Because the B- and C-family oxygen reductases lack the proton channel that is essential for transferring all of the pumped protons in the A-family enzymes, it is important to understand how this missing D-channel influences proton pumping in the B- and C-family enzymes.

Most previous proton pumping measurements have been performed with purified oxygen reductases reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Based on these measurements, it has been demonstrated that the A-family oxygen reductases pump one proton per electron (n = 1). Measurements on two different B-family enzymes (Thermus thermophilus and Geobacillus stearothermophilus) indicated a proton pumping stoichiometry of about 0.4 to 0.5 H+/e- (12, 13), whereas that from an enzyme related to the B-family (Acidianus ambivalens) suggested a value of closer to 0.75 (14). Proton pumping measurements on C-family oxygen reductases have provided no consensus, with values of n ranging from 0.1 to 1, using both reconstituted enzymes and whole cell measurements. Pumping measurements with whole cells of Paracoccus denitrificans and Rhodobacter sphaeroides showed that the C-family oxygen reductase pumps 1 H+/e- (15, 16). There is only one report using purified enzyme (Bradyrhizobium japonicum) reconstituted in proteoliposomes in which significant pumping was observed, with n values between 0.2 and 0.4 H+/e- (17). The proton pumping stoichiometry of the C-family remains an important open question.

In the current work, we use whole cell measurements to directly compare the proton pumping stoichiometries of the different heme-copper oxygen reductase families. The expected value of n = 1 was obtained for the A-family caa3 oxygen reductase from T. thermophilus. We also confirmed the value of n = 0.5 for the B-family ba3 oxygen reductase from T. thermophilus. C-family cbb3 oxygen reductases from three different bacteria were examined: Rhodobacter capsulatus, Helicobacter pylori, and R. sphaeroides. In each case, the proton pumping stoichiometry was about 0.5 H+/e-.

Results

Each of the five strains used in this work were selected or genetically engineered to express only one respiratory oxygen reductase (Table 1). In all cases, an artificial electron donor, N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD), was used rather than the endogenous substrates. Because TMPD provides electrons at the level of cytochrome c in the respiratory chain, only oxygen reductases that are able to receive electrons from cytochrome c are functional during the measurements. Inhibitors of the bc1 complex assured no oxidation of endogenous substrates. Furthermore, because the one-electron oxidation of TMPD above pH 7 results in the formation of a radical cation without the release of a proton from the substrate, all protons that appear in the external solution can be attributed to cellular processes.

Table 1.

Bacteria strains used in this study

| Strains |

Relevant characteristics |

Source |

| Rhodobacter capsulatus (SB1003) | ||

| WT | Wild-type | * |

| GK32 | Δcbb3 (C-family) | |

| KZ1 | Δqox (bd family) | * |

| Thermus thermophilus (HB8) | ||

| WT | Wild-type | † |

| YC1001 | Δba3 (B-family) | |

| KG100 | Δcaa3 (A-family) | ‡ |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides (2.4.1) | ||

| WT | Wild-type | |

| JR1000 | Δaa3 (A-family), Δcbb3 (C-family) | § |

| Helicobacter pylori (700392) | ||

| WT | Wild-type | ¶ |

*Fevzi Daldal, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

†James Fee, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA

‡Krithika Ganesan, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL

§Jung Hyeob Roh, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX

¶Vijay Gupta, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL

After washing fresh cultures with buffer it was found that neither T. thermophilus nor H. pylori exhibited oxygen reductase activity when suspended in oxygenated buffer. Upon adding substrate, such as succinate, oxygen reduction was observed confirming that the previous lack of oxygen reductase activity was due to rapid depletion of the endogenous substrates. All oxygen reductase activity was eliminated upon the addition of 10 μM myxothiazol, a bc1 complex inhibitor, or 100 μM potassium cyanide (KCN), which inhibits the oxygen reductases. The same treatment did not deplete either R. sphaeroides or R. capsulatus of endogenous substrates, as evidenced by robust oxygen reductase activity in the absence of any added substrate. Incubation of the fresh cultures at 30 °C for various times (several hours) also failed to eliminate the endogenous substrates, and after long periods of time (overnight), some cell death and other irreversible damage made the preparations unsuitable for use. However, in fresh cultures of R. sphaeroides or R. capsulatus it was found that 10 μM myxothiazol eliminated all oxygen reductase activity, blocking any reduction of the oxygen reductase from endogenous sources. The addition of 100 μM KCN also eliminated all respiration in both the R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus strains that were utilized. To validate these results the same procedure was performed on the R. capsulatus (GK32) strain, in which the cbb3 oxygen reductase has been eliminated by mutagenesis and only the bd-type oxygen reductase is expressed. In this case, because the bd-type oxygen reductase takes electrons directly from the quinol pool and is KCN resistant, neither myxothiazol nor KCN (up to 1 mM) inhibited oxygen respiration.

Having blocked oxygen respiration from endogenous sources, all pumping measurements were performed using TMPD as the exogenously added reductant. Ascorbate is often used in combination with TMPD to maintain the TMPD pool in a reduced state. However, it was observed that the presence of ascorbate resulted in apparent oxygen respiration that was not inhibited by either myxothiazol or by KCN (tested up to 1 mM) (Fig. 1A). This artifact is observed with whole cells, but not with isolated oxygen reductases. Because ascorbate was not utilized, TMPD, once oxidized, is not recycled. Upon oxidation TMPD forms a radical cation, Würster’s blue, which is readily observed as the solution turns a deep blue color. Direct oxidation of TMPD by O2 is sufficiently slow that it does not interfere with the pumping measurements.

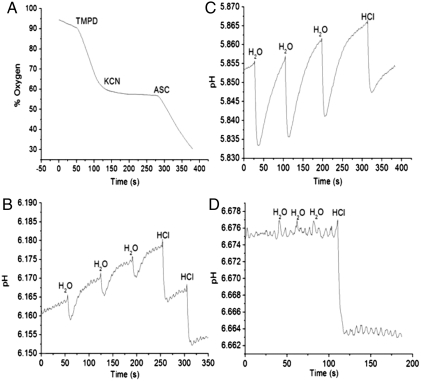

Fig. 1.

(A) Oxygen respiration by R. capsulatus (KZ1). TMPD (1 mM) was added to the cell suspension to initiate the reaction, 100 μM KCN was added to stop the reaction. The addition of 10 mM ascorbate results in the apparent resumption of oxygen respiration that does not respond to inhibitors of the respiratory chain. Hence, ascorbate was omitted from all solutions to avoid this artifact. (B and C) pH changes observed with O2 pulses to anaerobic suspensions of (B) T. thermophilus (YC 1001) and (C) R. capsulatus (KZ1) in the presence of myxothiazol. Air-saturated water (10 μL) was injected into the suspension three consecutive times followed by two injections of 10 μL of anaerobic 1 mM HCl. (D) The pH changes observed as in C for R. capsulatus except that the 100 μM KCN was present. Respiration-dependent proton pumping is blocked, but the addition of HCl generates the same drop in pH as in the absence of KCN.

Proton pumping measurements were performed with fresh cultures that were depleted (T. thermophilus and H. pylori) or partially depleted (R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus) of endogenous substrates. In all cases, 10 μM myxothiazol was utilized to block any endogenous source of electrons. Oxygen was partially eliminated by blowing Ar or N2 over the sealed sample compartment, after the addition of an anaerobic solution of reduced TMPD to a final concentration of 1 mM. Residual oxygen was eliminated by respiration at the expense of TMPD. After all the oxygen was eliminated, proton pumping was measured by the injection of air-saturated water and monitoring the change in pH. Fig. 1 B and C shows representative data for the transient pH changes observed with T. thermophilus (YC1001) and R. capsulatus (KZ1) which, respectively, encode an A-family (caa3) and C-family (cbb3) oxygen reductase. After several injections of air-saturated water, the system was calibrated by the addition of aliquots of 1 mM HCl. Fig. 1D shows that the addition of 100 μM KCN eliminates the proton release due to respiration. In the presence of ascorbate KCN did not stop proton release, therefore the elimination of the pumping signal by KCN serves as an important control to ensure that the activity measured is entirely due to the operation of the proton pumping oxygen reductase.

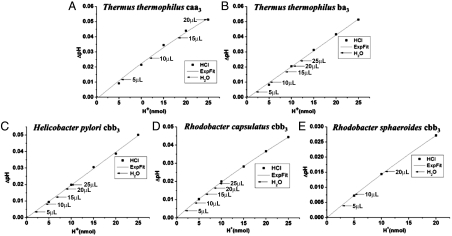

Fig. 2 shows the results obtained for each of the strains examined. The calibration curves show the change in pH (ΔpH) as a function of the amount of HCl added to the cell suspension, expressed as nanomoles of protons added to the solution. The horizontal lines indicate the values obtained upon the addition of different volumes of air-saturated water to the same cell suspension. The HCl-based calibration curve allows one to convert into the number of protons released from the cells due to the oxygen pulse. Because the amount of oxygen added to the solution is known, and all of it is reduced to water, the proton pumping stoichiometry is easily calculated. The results are summarized in Table 2. The pumping stoichiometry of the A-family caa3 oxygen reductase from T. thermophilus is close to the expected value of 1 H+/e-, matching previous measurements determined with the isolated enzyme (18). The pumping stoichiometry of the B-family ba3 oxygen reductase is approximately 0.5 H+/e-, confirming measurements with the isolated enzymes (12, 13). Most important, all three of the C-family cbb3 oxygen reductases clearly pump protons with a stoichiometry in the range of 0.4–0.5 H+/e-. Assuming that these values are likely to apply to other oxygen reductases within the same families, we conclude that both the B- and C-family oxygen reductases pump half the number of protons as the A-family enzymes.

Fig. 2.

Change in pH in a suspension of the indicated bacterial cells. The calibration curves (nmol H+ vs. ΔpH) were determined by adding aliquots of 1 mM HCl to the cell suspensions. To the same cell suspensions, aliquots of air-saturated water (25 °C) were added and the change in pH noted. The horizontal arrows each represent the addition of the indicated volume of air-saturated water. The calibration curve can be used to convert the measured ΔpH to nmol H+ injected into the solution. (A) T. thermophilus (YC1001). (B) T. thermophilus (KG100). (C) H. pylori (700392). (D) R. capsulatus (KZ1). (E) R. sphaeroides (JR1000).

Table 2.

Whole cell proton pumping measurements

| Oxygen reductase |

Family |

Source strain |

n (H+/e-) |

| caa3 | A-family | T. thermophilus (HB8) | 1.14 ± 0.12 |

| ba3 | B-family | T. thermophilus (HB8) | 0.52 ± 0.07 |

| cbb3 | C-family | H. pylori (700392) | 0.44 ± 0.05 |

| C-family | R. capsulatus (SB1003) | 0.41 ± 0.04 | |

| C-family | R. sphaeroides (2.4.1) | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

H+/e- ratios are averages ± standard deviation (n = 10). The exogenous substrate was TMPD. Anaerobic suspensions were pulsed with air-saturated H2O. Cells were cultivated as described in text.

Discussion

Aerobic respiration is one of the most important metabolisms to evolve on Earth, so it is imperative to understand the mechanism and evolution of the enzymes which perform this function. The different proton pumping efficiencies of the oxygen reductase families measured in this work has important implications for the mechanism of proton pumping, the adaptation of aerobic respiration to low oxygen environments, and the microbial ecology of aerobic respiration.

Implications for the Proton Pumping Mechanism.

The basic mechanism of O2 reduction appears to be essentially the same in the A-, B-, and C-families, with a unique active-site, cross-linked cofactor donating an electron and proton to break the O2 bond (9). All of the heme-copper oxygen reductase families are evolutionarily related, and the extant families appear to have evolved from a common ancestor (7). Phylogenetic and genomic analysis show that the B- and C-families evolved after the A-family, and evolutionary intermediates between the A-family and other families have been identified. As an example, the oxygen reductase from Nitrosopumilus maritimus has properties which suggest that it is an extant intermediate between the A- and B-families. It phylogenetically branches between the A- and B-families (19), and structurally has a D-channel identical to the A-family and a K-channel analogue closely related to that of the B-family. It is also missing subunit III, which is found in all other A-family members, but is absent from B-family members. These features provide evidence for the continuity of function during the evolutionary transitions between families, making it highly likely that all of the heme-copper oxygen reductase families share an evolutionarily conserved, universal mechanism for proton pumping.

Most models of proton pumping are based on an electrostatic coupling between electron and proton transfer in which a proton loading site alternates its protonation state during the catalytic cycle, coupled to the redox states of the metal cofactors or the net charge at the heme-copper active site. To ensure unidirectional proton pumping, the proton loading site can only be accessible from the cytoplasmic side during the loading phase, and during the unloading phase the protons must be released only to the periplasmic side. A number of models of the proton pumping mechanism have been proposed for the oxygen reductases in either the A- or B-families, but all of these models contain features which are unique to the individual oxygen reductase families studied (3, 20–26). One model proposes a unique mechanism specifically for A-family oxygen reductases found in Metazoan mitochondria (27).

A general model of proton pumping should be applicable to all of the heme-copper oxygen reductase families and include the following elements: (i) details of how the chemistry of oxygen reduction is coupled to proton pumping, (ii) the molecular mechanism of the differential coupling stoichiometries, (iii) a proton loading site that alternates between protonated (high-pKa) and deprotonated (low-pKa) states, and (iv) kinetic gates which assure that the protons arriving at the proton loading site in the deprotonated state come from the inside aqueous phase (cytoplasm/matrix) and protons ejected from the proton loading site in the protonated state are released to the outside aqueous phase (periplasm/intermembrane space).

The key elements, i.e., the proton loading site and kinetic gating mechanism(s), are likely to be structurally conserved and the same for all families (10, 28). Electrometric measurements (29), computational studies (30), and comparative structural analyses (10) have led to the proposal that the A-propionate of the active site heme may be the universal proton loading site (10). A recently published structure of a C-family member (31) verified that the A-propionate region of the active site heme is one of the few structural elements that is shared by all of the heme-copper oxygen reductase families, supporting its proposed role.

A general model of proton pumping has to explain the differential coupling stoichiometries between the oxygen reductase families. Detailed spectroscopic studies have identified the steps of the catalytic cycle coupled to proton pumping in a number of members of the A-family. Similar studies on a member of the B-family has demonstrated that proton pumping is not associated with the PR → F transition (32–34), partially explaining the decreased proton pumping coupling stoichiometry of the B-family when compared to the A-family. It is unknown why proton pumping is associated with only two of the four electron transfer reactions in the B- and C-families.

The current work shows that the channel properties of the A-, B-, and C-family enzymes correlate with the coupling stoichiometries. Perhaps the structural details of the channels and/or the kinetics of proton transfer through the different channels play important roles in determining the coupling stoichiometry. Further studies will be required to determine the detailed mechanism of decreased coupling stoichiometry in the B- and C-families.

Adaptation of Aerobic Respiration to Low Oxygen Environments.

Members of the B- and C-families have high apparent affinities for O2 and are usually expressed in organisms under low O2 or microaerobic conditions, such as at high temperatures, oxic/anoxic interfaces, or in suboxic hypersaline mats. However, the lowered proton pumping stoichiometry in the B- and C-families is energetically disadvantageous compared to the A-family, requiring more O2 (the limiting substrate in microaerobic environments) to be consumed to generate an equivalent membrane potential. In the context of a complete respiratory chain from NADH to O2, changing the pumping stoichiometry of the oxygen reductase from 1.0 to 0.5 H+/e- would result in the expected number of charges driven across the membrane to drop from 20 charges per O2 to 18 charges per O2, a decrease of 10%. The decrease in energy conservation per O2 will be substantially larger when the electrons enter further downstream in the respiratory chain, such as in sulfur or iron oxidation.

It is not clear why nature would select for a less efficient enzyme in environments in which oxygen is limiting, unless it is the result of either physical or evolutionary constraints. At ambient temperature, the dissolved O2 concentration in water is on the order of 250 μM. Microbes that grow microaerobically may be challenged to survive at concentrations of dissolved O2 in the nanomolar range or below (35). It is possible that either the thermodynamic or kinetic consequences of operating at nanomolar oxygen levels might have been the driving force behind the loss of the D-channel and the lower proton pumping stoichiometries in the B- and C-families.

Thermodynamics.

The low concentration of O2 reduces the magnitude of the reaction free energy of oxygen reduction by mass action. The reduction potential of the O2/H2O redox pair changes from the standard state value (298 K) of about 815 mV to 680 mV at 10-9 M O2 (15 mV per 10-fold decrease in O2 concentration because oxygen reduction is a four electron reaction). Thermodynamics would require a lower proton pumping stoichiometry only if the oxygen reductase could not drive eight charges per O2 across the membrane against the minimum value of ΔΨ required for ATP synthesis. However, the reduction of O2 is so exergonic that even at 10-9 M O2 there is sufficient available free energy to transfer eight charges and power the cellular processes without compromise. Thus, the reduced proton pumping stoichiometry of the B- and C-families is not required by thermodynamic constraints.

Kinetics.

The maximum turnover of the oxygen reductases is typically in the range of 100–1,000 electrons/s. If the second order rate constant for the initial reaction of O2 with the enzyme is 108 M-1 s-1 [the value measured for the A-family (36)], then at 10-9 M O2 the formation of the initial complex between the enzyme and oxygen will be rate limiting at about 10-1 s-1. Even though the O2 concentration within the hydrophobic lipid membrane is higher than in water, the rate of respiration might be too slow to maintain the necessary membrane potential.

At very low oxygen concentrations, the overall rate of the oxygen reduction reaction will be determined by the rate of O2 diffusion into the active site. Therefore, it is plausible that in the B- and C-families evolution has selected for structural features which increase the rate of O2 diffusion within the protein. O2 is nonpolar and is transported to the active site via channels lined with hydrophobic residues. In the A-family, site-directed mutagenesis and noble gas pressurized crystallography, which identifies hydrophobic cavities within proteins, delineated a likely oxygen channel which has a single entrance within the lipid bilayer and runs along the edge of the D-channel to the active site (37). However, noble gas pressurized crystallography on the ba3 oxygen reductase from T. thermophilus demonstrated that the oxygen input channel in the B-family has two openings and, most importantly, runs through the center of the pore where the D-channel analogue would be located (38). Analysis of the C-family also identified a large pore with two openings structurally very similar to that in the B-family (31). The second order rate constant for the initial reaction of O2 with the T. thermophilus B-family oxygen reductase is 109 M-1 s-1 (36), 10 times higher than in the A-family (39), providing support for the hypothesis that the larger oxygen channels in the B- and C-families are evolutionary adaptations to increase the O2 diffusion rate to the active site. The higher diffusion rate would allow the B- and C-families to maintain physiologically relevant reaction rates in low O2 environments.

The hydrophobic nature of the oxygen channel precludes the simultaneous presence of a hydrophilic proton channel in the same physical region of the protein. We propose that this incompatability is the driving force for the evolutionary loss of the D-channel in the B- and C-families. For unknown reasons, the lack of a D-channel results in a lower proton pumping stoichiometry for the B- and C-family enzymes. It is interesting to note that the adaptation to low O2 environments may not necessarily require a loss of proton pumping efficiency, but may be the result of evolutionary constraints on the protein structure.

Implications for the Microbial Ecology of Oxygen Utilization.

The majority of sequenced microbes (57%) capable of performing aerobic respiration encode multiple heme-copper oxygen reductases within their genomes, with some having as many as eight. This level of diversity clearly suggests that all of the heme-copper oxygen reductases, though biochemically redundant, are not physiologically redundant. Furthermore, many organisms differentially regulate expression of their heme-copper oxygen reductases depending on the environmental conditions (40, 41), suggesting that differences in oxygen affinity, proton pumping efficiency, and availability of electron donors play important roles in determining when individual oxygen reductases are useful for the organism. Organisms encoding members of the B- or C-families likely can either tolerate, or adapt to, low oxygen environments, thereby partially determining the organisms ecological niche. Neutrophilic iron oxidation is an example of a metabolism which requires low oxygen environments. To compete with abiological iron oxidation these organisms are forced to grow at submicromolar O2 levels (42). Prokaryotic A-family oxygen reductases apparently cannot function at such low oxygen concentrations, however B- and C-family members can. All of the currently sequenced neutrophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria encode C-family oxygen reductases, with all but one encoding only C-family members.

The evolution of aerobic respiration provided life with access to many redox-coupled reactions that were previously unavailable, significantly increasing the number of available ecological niches. The eventual adaptation of aerobic respiration to low O2 environments extended the number of available ecological niches, further expanding the diversity of microbial life.

Materials and Methods

More details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Bacterial Strains.

The properties of the six strains used in this work are described in Table 1. When necessary the strains were engineered to contain only one oxygen reductase.

Bacterial Growth Conditions.

The strains were grown as previously described.

Whole Cell Oxygen Reductase Activity Measurements.

The steady-state oxygen reductase activity was measured at 25 °C with a YSI model 53 oxygen monitor. The endogenous substrates were eliminated by the addition of either 10 μM myxothiazol, which inhibits the bc1 complex (ubiquinol∶cytochrome c oxidoreductase), or 100 μM KCN, which inhibits the heme-copper oxygen reductases. After obtaining a baseline of oxygen consumption, TMPD was added to a final concentration of 1 mM to initiate the oxygen reduction reaction. 100 μM KCN was used to stop the reaction, assuring that the reaction was catalyzed by the respiratory oxygen reductase.

Whole Cell Proton Pumping Measurements.

Whole cell pumping experiments were performed using a pH meter. The washed, intact cells were suspended in a gas-tight vessel in 0.5 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM KCl, 100 mM potassium thiocyanate and 10 μM myxothiazol. After the pH of the solution reached a constant value and was equilibrated, various amounts of air-saturated water (5–25 μL), equilibrated at 25 °C, were added to the solution and the change in pH was monitored. The pH changes were calibrated by the addition of various amounts (5–25 μL) of a 1 mM solution of HCl. The procedure was repeated after the addition of KCN to a final concentration of 100 μM to verify that the measured proton pumping was due to the heme-copper oxygen reductase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL16101 (to R.B.G.), AI0045928 (to S.R.B.), and GM38237 (to F.D.); and Department of Energy Grant 91ER20052 (to F.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1018958108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Falkowski PG, Fenchel T, Delong EF. The microbial engines that drive Earth’s biogeochemical cycles. Science. 2008;320:1034–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1153213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosler JP, Ferguson-Miller S, Mills DA. Energy transduction: Proton transfer through the respiratory complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:165–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.062003.101730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Mechanism and energetics of proton translocation by the respiratory heme-copper oxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:1200–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ. Bioenergetics 3. 3rd Ed. London: Academic; 2002. pp. 89–156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon J, van Spanning RJ, Richardson DJ. The organization of proton motive and non-proton motive redox loops in prokaryotic respiratory systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1480–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gennis RB. Coupled proton and electron transfer reactions in cytochrome oxidase. Front Biosci. 2004;9:581–591. doi: 10.2741/1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemp J, Gennis RB. Diversity of the heme-copper superfamily in Archaea: Insights from genomics and structural modeling. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2008;45:1–31. doi: 10.1007/400_2007_046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira MM, Santana M, Teixeira M. A novel scenario for the evolution of heme-copper oxygen reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1505:185–208. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemp J, et al. Evolutionary migration of a post-translationally modified active-site residue in the proton-pumping heme-copper oxygen reductases. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15405–15410. doi: 10.1021/bi062026u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang HY, Hemp J, Chen Y, Fee JA, Gennis RB. The cytochrome ba3 oxygen reductase from Thermus thermophilus uses a single input channel for proton delivery to the active site and for proton pumping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16169–16173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905264106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemp J, et al. Comparative genomics and site-directed mutagenesis support the existence of only one input channel for protons in the C-family (cbb3 oxidase) of heme-copper oxygen reductases. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9963–9972. doi: 10.1021/bi700659y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kannt A, et al. Electrical current generation and proton pumping catalyzed by the ba3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. FEBS Lett. 1998;434:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00942-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikaido K, Sakamoto J, Noguchi S, Sone N. Over-expression of cbaAB genes of Bacillus stearothermophilus produces a two-subunit SoxB-type cytochrome c oxidase with proton pumping activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1456:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes CM, et al. Heme-copper oxidases with modified D- and K-pathways are yet efficient proton pumps. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:159–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Gier JW, et al. The terminal oxidases of Paracoccus denitrificans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toledo-Cuevas M, Barquera B, Gennis RB, Wikstrom M, Garcia-Horsman JA. The cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, a proton-pumping heme-copper oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:421–434. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arslan E, Kannt A, Thony-Meyer L, Hennecke H. The symbiotically essential cbb3-type oxidase of Bradyrhizobium japonicum is a proton pump. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hon-Nami K, Oshima T. Purification and some properties of cytochrome c-552 from an extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus HB8. J Biochem. 1977;82:769–776. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker CB, et al. Nitrosopumilus maritimus genome reveals unique mechanisms for nitrification and autotrophy in globally distributed marine crenarchaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8818–8823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913533107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fadda E, Yu CH, Pomes R. Electrostatic control of proton pumping in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fee JA, Case DA, Noodleman L. Toward a chemical mechanism of proton pumping by the B-type cytochrome c oxidases: Application of density functional theory to cytochrome ba3 of Thermus thermophilus. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15002–15021. doi: 10.1021/ja803112w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsson MH, Sharma PK, Warshel A. Simulating redox coupled proton transfer in cytochrome c oxidase: Looking for the proton bottleneck. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2026–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popovic DM, Stuchebrukhov AA. Proton pumping mechanism and catalytic cycle of cytochrome c oxidase: Coulomb pump model with kinetic gating. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quenneville J, Popovic DM, Stuchebrukhov AA. Combined DFT and electrostatics study of the proton pumping mechanism in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharpe MA, Ferguson-Miller S. A chemically explicit model for the mechanism of proton pumping in heme-copper oxidases. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9182-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegbahn PE, Blomberg MR. Proton pumping mechanism in cytochrome c oxidase. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:12772–12780. doi: 10.1021/jp801635c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimokata K, et al. The proton pumping pathway of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4200–4205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611627104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira MM, Sousa FL, Verissimo AF, Teixeira M. Looking for the minimum common denominator in heme-copper oxygen reductases: Towards a unified catalytic mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:929–934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belevich I, Bloch DA, Belevich N, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Exploring the proton pump mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase in real time. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2685–2690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608794104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaila VR, Sharma V, Wikstrom M. The identity of the transient proton loading site of the proton-pumping mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buschmann S, et al. The structure of cbb3 cytochrome oxidase provides insights into proton pumping. Science. 2010;329:327–330. doi: 10.1126/science.1187303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siletsky SA, et al. Time-resolved single-turnover of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siletsky SA, Belevich I, Wikstrom M, Soulimane T, Verkhovsky MI. Time-resolved OH → EH transition of the aberrant ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smirnova IA, Zaslavsky D, Fee JA, Gennis RB, Brzezinski P. Electron and proton transfer in the ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:281–287. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9157-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolper DA, Revsbech NP, Canfield DE. Aerobic growth at nanomolar oxygen concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18755–18760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013435107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szundi I, Funatogawa C, Fee JA, Soulimane T, Einarsdottir O. CO impedes superfast O2 binding in ba3 cytochrome oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21010–21015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008603107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svensson-Ek M, et al. The X-ray crystal structures of wild-type and EQ(I-286) mutant cytochrome c oxidases from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luna VM, Chen Y, Fee JA, Stout CD. Crystallographic studies of Xe and Kr binding within the large internal cavity of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: Structural analysis and role of oxygen transport channels in the heme-Cu oxidases. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4657–4665. doi: 10.1021/bi800045y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verkhovsky MI, Morgan JE, Wikstrom M. Oxygen binding and activation: Early steps in the reaction of oxygen with cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3079–3086. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Auernik KS, Kelly RM. Identification of components of electron transport chains in the extremely thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon Metallosphaera sedula through iron and sulfur compound oxidation transcriptomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7723–7732. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01545-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackenzie C, et al. Postgenomic adventures with Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:283–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emerson D, Fleming EJ, McBeth JM. Iron-oxidizing bacteria: An environmental and genomic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:561–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.