Abstract

Objective To determine the prevalence, impact, and stability of different subtypes of headache in a 30 year prospective follow-up study of a general population sample.

Design Prospective cohort study.

Setting Canton of Zurich, Switzerland.

Participants 591 people aged 19-20 from a cohort of 4547 residents of Zurich, Switzerland, interviewed seven times across 30 years of follow-up.

Main outcome measures Prevalence of headache; stability of the predominant subtype of headache over time; and age of onset, severity, impact, family history, use of healthcare services, and drugs for headache subtypes.

Results The average one year prevalences of subtypes of headache were 0.9% (female:male ratio of 2.8) for migraine with aura, 10.9% (female:male ratio of 2.2) for migraine without aura, and 11.5% (female:male ratio of 1.2) for tension-type headache. Cumulative 30 year prevalences of headache subtypes were 3.0% for migraine with aura, 36.0% for migraine without aura, and 29.3% for tension-type headache. Despite the high prevalence of migraine without aura, most cases were transient and only about 20% continued to have migraine for more than half of the follow-up period. 69% of participants with migraine and 58% of those with tension-type headache manifested the same predominant subtype over time. However, the prospective stability of the predominant headache subtypes was quite low, with substantial crossover among the subtypes and no specific ordinal pattern of progression. A gradient of severity of clinical correlates and service use was present across headache subtypes; the greatest effect was for migraine with aura followed by migraine without aura, and then tension-type headache and unclassified headaches.

Conclusions These findings highlight the importance of prospective follow-up of people with headache. The substantial longitudinal overlap among subtypes of headache shows the developmental heterogeneity of headache syndromes. Studies of the causes of headache that apply diagnostic nomenclature based on distinctions between discrete headache subtypes may not capture the true nature of headache in the general population.

Introduction

A substantial body of international research documents the high prevalence and serious functional impairment associated with migraine.1 The rates of migraine and other subtypes of headache are remarkably similar across the world, with aggregate one year prevalence estimates of 10% for migraine and 38% for tension-type headache in adults.2 Migraine with aura is less common, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.0-2.3%.3 4 Severe headaches and migraine not only have a substantial effect on the affected person but also have major economic impact as a result of medical expenses and employers’ costs.5 For example, the annual direct medical cost attributable to migraine in the United States was estimated at $1bn (£0.61bn; €0.7bn) in 1999.6

Despite the large body of cross sectional studies on the prevalence and correlates of migraine, prospective research from community samples that provides information on the incidence, stability, and course of migraine in adults is lacking. Three prospective community surveys of adults and one of children have reported incidence data,7 8 9 10 but the longitudinal course of specific headache subtypes in adults has been studied in only one 12 year prospective study of a community sample with a single follow-up interview of adults ages 25-64 in Denmark.11 This study reported substantial longitudinal overlap between migraine and tension-type headache and worse long term outcome in terms of severity and recurrence among people with coexisting migraine and tension-type headache.11 In contrast to the limited number of prospective studies of adults with migraine, several long term follow-up studies of school based and clinical samples of specific childhood headache subtypes have been done.12 13 14 In a 40 year follow-up of a sample of Swedish schoolchildren with headache, Bille found that about 30% of those with childhood headaches developed chronic headache in adulthood, 20% had intermittent attacks, and 50% no longer reported headaches in adulthood.14 Similar proportions have been found in follow-up studies of adults with migraine.11

Our study provides the first long term prospective study of ICHD-2 (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) defined subtypes of headache in a community sample with multiple in-person interviews over a 30 year follow-up period. The objectives of this paper are to present estimates of the prevalence of common headache subtypes in young adults as they progress through early to middle adulthood; to examine the stability of the predominant headache subtypes over time; and to evaluate the course, impact, use of healthcare services, and severity of common headache subtypes.

Methods

Setting and participants

The Zurich Cohort Study comprises a cohort of 4547 people (2201 men; 2346 women) representative of the canton of Zurich in Switzerland in 1978. At that time, the male participants were 19 years old (at mandatory conscription) and the female participants were 20 years old (complete electoral register). The response rate for men was 99.7%. Women were identified at the age of 20 by the complete electoral register; half of the women chosen randomly received mailed questionnaires, and 75% of them responded. Binder and colleagues have presented details of the original study aims and sampling procedures.15 Briefly, the goal of the study was to examine the prevalence, course and outcome, impairment, and overlap among minor psychological disturbances and somatic syndromes in a sample from the general population. A screening scale for physical and emotional symptoms, the Symptom Checklist 90-R,16 was administered to prospective study participants. To enrich the probability of psychiatric syndromes, a stratification procedure based on over-sampling of those whose score exceeded the 85th centile of the Symptom Checklist 90-R global severity index score was applied as described by Dunn.17 In total, 591 participants (292 men, 299 women) were selected for interview. Two thirds of the interview sample comprised high scorers and one third were randomly selected from the remainder of the initial sample (global severity index scores below the 85th centile). The prevalence estimates reported at each wave of the study were weighted to yield unbiased population estimates, as described by Eich and Rössler.18 19

The interview sample had face to face interviews at ages 21, 23, 28, 30, 35, 41, and 50 years for women; men were one year younger at all interviews (fig 1). The entire cohort was contacted at each wave irrespective of participation at the previous interview wave. Over 30 years, 43% of the cohort participated in all seven interviews, 55% in six interviews, 66% in five interviews, 75% in four interviews, 83% in three interviews, and 91% in at least two interviews. On average, about 10% of the participants dropped out at each interview wave. Previous analyses showed that those who dropped out did not differ significantly from those who continued to participate with respect to psychiatrically relevant demographic characteristics.18 We further analysed differences in participation rates by sampling group (high v low global severity index scorers), sex, and headache status at study entry by subgroups used in longitudinal analyses. We found no significant differences by risk group, sex, or headache status in these subgroups.

Fig 1 Sample and design of Zurich Cohort Study, 1978-2008

Measures

Medical residents and clinical psychologists with extensive clinical training administered the Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of the Social Consequences for Epidemiology (SPIKE), with modules for psychiatric and somatic disorders, in the participants’ homes.20 Screening probes based solely on the major phenomenological features of each syndrome (such as depressed, irritable, sad mood) were administered for each diagnostic category. Separate modules covered the descriptive phenomenology of psychiatric syndromes including depression, fears/phobias, panic attacks, generalised anxiety, hypomania, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating behaviours, post-traumatic stress, behaviour problems, suicidality, and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use. The successive versions of SPIKE have enabled application of the diagnostic criteria for DSM-III (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition), DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV.21 22 23 Interviews included many demographic and social status measures, some at only one interview and others at multiple interviews. Other measures such as personality traits, social supports, life events, and quality of life were also included.

Headache symptoms and disorders

The interview also assesses several somatic syndromes, including insomnia, headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, cardiovascular symptoms, respiratory symptoms, menstrual symptoms, and sexual syndromes. The entry question for the headache section inquired about whether the participant had had headaches or migraine during the previous 12 months (“Have you suffered from headaches or migraine during the past 12 months?” or, in German, “Haben Sie in den letzten 12 Monaten Kopfschmerzen oder Migräne gehabt?”). If the answer was positive, the entire headache module was administered. The key phenomena included symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhoea, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to noise, sensitivity to smell, difficulty thinking, fatigue); prodrome (13 features of aura, then the timing and duration with respect to headache); characteristics of headache (quality and location of the pain); severity (from mild to extreme); effect on work; location (unilateral, moving from one side to the other); precipitating factors (12 situations, triggers); frequency/duration/number and timing of headaches and headache episodes during previous year; work/social impairment (analogue and categorical ratings); and treatment (type of specialist, specific drug(s), over the counter drugs). These questions were then followed by a section that was completed by all participants, including those with headache during the previous 12 months, about 12 symptoms of headaches during the interim period and treatment for headaches in each of the years since the previous interview.

We assessed the impact of headache with dimensional analogue measures of distress and work impairment and the number of days in the previous year with headaches. We also examined treatment contacts and prescribed and non-prescribed drug use. Irrespective of whether the respondent confirmed the presence of headaches during the previous year, we collected a history of headaches and treatment for headache in the years between the interviews. We also created a cumulative variable for the number of years of the 30 year study period that the person experienced headaches, as well as treatment for headaches. The family history of headache and treatment for headache among parents and siblings enumerated individually was collected at two of the interviews.

Sufficient information on symptoms was available for us to ascertain the criteria of the ICHD-2 for migraine with aura, migraine without aura, and tension-type headache from the last five waves of the study. Most of the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine without aura were also collected at the first two study interviews, but the interview did not include all of the criteria for aura. However, this community survey included no physical or neurological examination as required by the ICHD-2. Experienced neurologists (HI and SK) reviewed the diagnostic criteria for the specific subtypes of headache across all the study interviews.24 25 Merikangas et al have reported previous findings on headache in the Zurich Study.24 Because many of the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine and tension-type headache are mutually exclusive, participants could have only one specific subtype at each time point.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence

The analysis includes both 12 month and cumulative prevalence rates. Cumulative rates are based on the 12 month prevalences across the seven interviews as the cohort progressed from ages 20 to 50. We used the Kaplan-Meier product limit method to calculate non-parametric estimates of the cumulative incidence of migraine.

Impact and clinical correlates

We used analysis of variance to compare the means of severity, work impairment, and duration of headache/treatment among headache subtypes. We used Duncan’s test to evaluate multiple comparisons. We used logistic regression to investigate the associations between consultation/treatment/drug and headache groups while controlling for sex.

Stability and crossover

To examine the stability, or extent to which participants manifest the same predominant headache subtype over time, we examined the proportions of participants who met the criteria for the same predominant subtype of headache and those who manifested combinations of the three major subtypes. For these analyses, we included a subset of people who had participated in at least four interviews and who had a diagnosis of one of the primary headache subtypes in at least one interview. We also evaluated the longitudinal stability of the predominant headache subtypes across 30 years by selecting people with migraine and tension-type headache in at least one of the first three waves and assessed the proportion who met all combinations of subtypes across the 30 year follow-up. We used SAS 9.2 for all the analyses. We included all available information in the analyses, so participants with partial data were included. We did not impute missing values.

Results

Prevalence

Table 1 shows the total and sex specific weighted rates of headache subtypes across 30 years. The average one year prevalence of migraine with aura was 0.9%, with a total prevalence of 3.0% (3.9% in women; 2.1% in men). The weighted prevalences of migraine without aura ranged from 8.3% to 14.8% with a median of 10.1%. The total prevalence of migraine without aura was 36.0%, with a female specific rate of 50.7% and a male specific rate of 20.7%. The cumulative lifetime prevalence of tension-type headache was 29.3%; one year prevalences ranged from 5.7% to 19.4 % across the 30 year follow-up, with a median of rate of 8.5%. The average prevalence of daily headache was about 1%. The prevalence of migraine without aura tended to decrease over time, whereas the prevalence of tension-type headache tended to increase in the 20s and 30s, peaking at age 40. Men had greater cumulative prevalences of tension-type headache, whereas women had greater rates of migraine with and without aura.

Table 1.

Sex specific one year weighted rates (percentages) of mutually exclusive headache subtypes across 30 years (n=591)

| Year and sex | Migraine with aura | Migraine without aura | Tension-type headache | Other headache | No headache |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979: | |||||

| Male | – | 10.6 | 5.4 | 43.2 | 40.8 |

| Female | – | 18.8 | 11.6 | 46.8 | 22.8 |

| Total | – | 14.8 | 8.5 | 45.0 | 31.7 |

| 1981: | |||||

| Male | – | 4.8 | 6.2 | 24.5 | 64.5 |

| Female | – | 19.5 | 5.2 | 34.6 | 40.7 |

| Total | – | 12.3 | 5.7 | 29.6 | 52.4 |

| 1986: | |||||

| Male | 0.9 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 22.4 | 65.5 |

| Female | 1.5 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 28.0 | 48.3 |

| Total | 1.2 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 25.3 | 56.7 |

| 1988: | |||||

| Male | 1.0 | 5.1 | 8.4 | 19.2 | 66.3 |

| Female | 2.0 | 15.0 | 8.5 | 23.1 | 51.4 |

| Total | 1.5 | 10.1 | 8.4 | 21.2 | 58.8 |

| 1993: | |||||

| Male | 0.2 | 6.9 | 21.3 | 10.1 | 61.5 |

| Female | 1.3 | 16.6 | 14.7 | 15.4 | 52.0 |

| Total | 0.8 | 11.8 | 18.0 | 12.8 | 56.6 |

| 1999: | |||||

| Male | 0.1 | 7.2 | 16.0 | 12.9 | 63.8 |

| Female | 1.9 | 12.9 | 22.8 | 15.6 | 46.8 |

| Total | 1.0 | 10.1 | 19.4 | 14.3 | 55.2 |

| 2008: | |||||

| Male | 0.1 | 7.6 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 74.3 |

| Female | 0.3 | 10.4 | 13.8 | 16.5 | 59.0 |

| Total | 0.2 | 9.0 | 11.7 | 12.6 | 66.5 |

| Cumulative: | |||||

| Male | 2.1 | 20.7 | 34.1 | 26.8 | 16.3 |

| Female | 3.9 | 50.7 | 24.6 | 14.2 | 6.6 |

| Total | 3.0 | 36.0 | 29.3 | 20.4 | 11.3 |

| Average 1 year: | |||||

| Male | 0.5 | 6.8 | 10.4 | 20.1 | 62.2 |

| Female | 1.4 | 15.1 | 12.5 | 25.5 | 45.5 |

| Total | 0.9 | 10.9 | 11.5 | 23.0 | 53.7 |

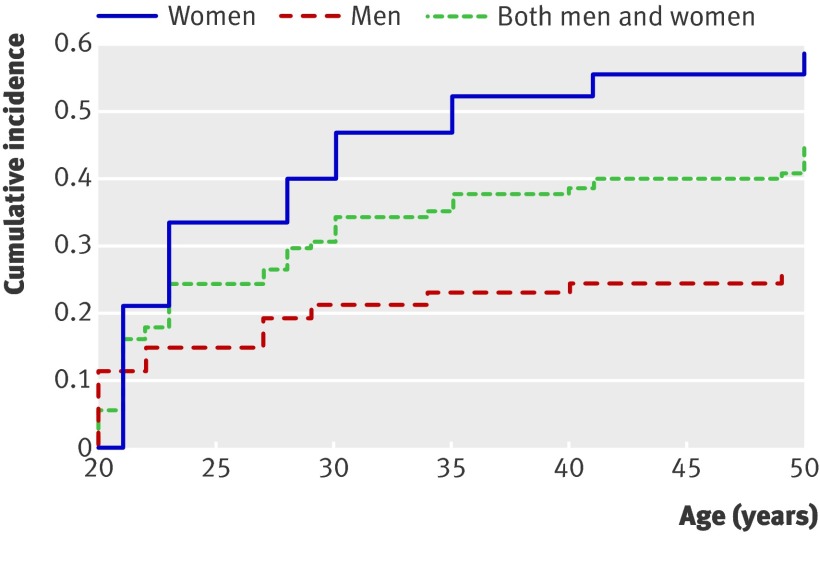

Figure 2 shows the sex specific cumulative survival analysis of the incidence of migraine across the 30 year study. Women had higher incidences and a steeper increase in onset of migraine than did men across the entire follow-up period. Incidence in men levelled off at age 35, whereas that in women continued to increase to age 50.

Fig 2 Cumulative incidence of migraine across 30 years (n=591)

Impact and clinical correlates

Table 2 shows the clinical correlates and impact associated with the various subtypes of headache. A decreasing gradient of levels of distress, impairment, and duration by severity of headache subtype can be seen. People with migraine with aura had the greatest level of distress (81.1), followed by 70.0 for migraine without aura, 47.4 for tension-type headache, and 45.4 for other headache. A similar decreasing gradient emerged for the analogue rating of work impairment: 65.9 for migraine with aura, 60.8 for migraine without aura, 39.5 for tension-type headache, and 29.1 for other headache. Participants with migraine with aura had significantly greater numbers of years with migraine than did those without aura, but they had comparable levels of distress, work impairment, number of days a year with headache, and proportion of years treated. Migraine was associated with greater levels of severity and treatment indicators than was tension-type headache.

Table 2.

Clinical correlates and impact by mutually exclusive headache subtypes. Values are weighted mean (SE, range) unless stated otherwise

| Impact/correlates | No | Total (n=532) | Migraine with aura (n=26) | Migraine without aura (n=224) | Tension-type headache (n=153) | Other headache (n=129) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distress (0-100) | 462 | 58.9 (1.4, 0-100) | 81.1 (4.1, 40-100)‡ | 70.0 (1.8, 0-100)‡ | 47.4 (2.2, 0-100)§ | 45.4 (4.4, 0-100)§ |

| Work impairment (0-100) | 391* | 49.4 (1.7, 0-100) | 65.9 (5.1, 10-100)‡ | 60.8 (2.3, 0-100)‡ | 39.5 (2.6, 0-100)§ | 29.1 (4.6, 0-100)§ |

| Years with symptoms 1978-2008 (%) | 532 | 59.6 (1.3, 3.2-100) | 86.7 (3.8, 48.4-100)‡ | 75.6 (1.5, 9.7-100)§ | 55.6 (2.3, 3.2-100)¶ | 33.9 (2.1, 3.2-100) |

| Years treated 1978-2008 (%) | 532 | 5.8 (0.6, 0-100) | 9.3 (2.5, 0-58.1)‡ | 11.4 (1.2, 0-100)‡ | 1.9 (0.4, 0-35.5)§ | 1.2 (0.4, 0-50)§ |

| Days/year with headache (1993, 1999, and 2008) | 345† | 24.8 (2.1, 0-300) | 27.4 (6.7, 2-200)‡§ | 33.7 (3.7, 2-300)‡ | 15.5 (1.8, 1-200)‡§ | 12.1 (3.6, 0-60)§ |

| Family history (% (SE)): | ||||||

| Parents | 428 | 71.6 (2.2) | 93.5 (4.9)‡ | 75.1 (3.1)§ | 72.4 (4.0)§ | 54.5 (5.6)¶ |

| Siblings | 428 | 36.6 (2.3) | 69.9 (9.2)‡ | 34.0 (3.4)§ | 35.6 (4.3)§ | 36.7 (5.4)§ |

| Either | 480 | 80.6 (1.8) | 96.1 (3.9)‡ | 84.5 (2.5)‡ | 86.7 (2.9)‡ | 58.7 (4.8)§ |

*Some female participants did not work.

†Based on information from 1993, 1999, and 2008 interviews.

दMeans/rates with same symbol are not significantly different (Duncan test).

Table 2 also shows the percentage of years from the start of the study in which the respondents had headaches. These ratings comprise a combination of the prospective interviews and retrospective inter-interview intervals. The average proportion of time that participants with the various subtypes of headache reported that they had symptoms was 86.7% (SE 3.8%) for migraine with aura, 75.6% (1.5%) for migraine without aura, 55.6% (2.3%) for tension-type headache, and 33.9% (2.1%) for other headache. Estimates of the number of days a year with headache collected at the last three interviews were higher for migraine with and without aura (27.4 (6.7) and 33.7 (3.7)) than for tension-type headache (15.5 (1.8)) and other headache (12.1 (3.6)). A similar gradient across headache subtypes emerged for family history of headaches. Ninety-four per cent of participants with migraine with aura, 75% of those with migraine without aura, and 72% of those with tension-type headache reported a parental history of headaches, and 70%, 34%, and 36% reported a history of headaches in their siblings.

Table 3 shows the patterns of treatment and drug use by subtypes of headache. A similar decreasing gradient with decreasing severity of headache subtype emerged for all of the service measures including treatment, consultation with a physician, and prescribed and non-prescribed drug use. Sixty-six per cent of participants with migraine with aura reported any treatment, and 43% had consulted a physician, compared with 57% and 36% among those with migraine without aura. Only a minority of people with tension-type headache or unclassified headache reported treatment or medical consultation.

Table 3.

Weighted rates of treatment and drug use by mutually exclusive headache subtypes

| Treatment/drugs | Weighted rate (% (No)) | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=532) | Migraine with aura (n=26) | Migraine without aura (n=224) | Tension-type headache (n=153) | Other headache (n=129) | Migraine with aura v migraine without aura | Migraine v tension-type headache | Tension-type headache v other headache | ||

| Consulted doctor | 23.0 (118) | 43.4 (13) | 36.3 (77) | 12.9 (17) | 6.0 (11) | 1.6 (0.99 to 2.5) | 3.0 (2.3 to 3.8)† | 2.5 (1.7 to 3.8)† | |

| Treatment | 36.6 (205) | 65.7 (20) | 57.4 (128) | 28.0 (41) | 8.8 (16) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.5)† | 3.9 (2.8 to 5.5)† | |

| Drug: | |||||||||

| Prescribed | 15.1 (81) | 39.5 (10) | 27.3 (56) | 8.5 (14) | 0.2 (1) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9)† | 3.8 (2.8 to 5.1)† | –‡ | |

| Non-prescribed | 54.5 (298) | 81.6 (22) | 72.6 (165) | 58.5 (92) | 13.3 (19) | 1.6 (0.9 to 3.0) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6)† | 9.5 (7.1 to 12.7)† | |

| Either | 57.1 (305) | 81.6 (22) | 77.6 (170) | 60.0 (93) | 13.5 (20) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 2.4 (1.9 to 3.0)† | 9.7 (7.3 to 12.9)† | |

*From logistic regression.

†Significant at P<0.05.

‡Only one participant in “other headache” group.

Most participants with any of the headache subtypes used drugs (82% for migraine with aura, 78% for migraine without aura, 60% for tension-type headache, and 14% for other headache). We also found a significant difference between headache subtypes in the proportion of people who had used prescription drugs, which ranged from 40% of those with migraine with aura to less than 1% of those with other headache.

Stability and crossover

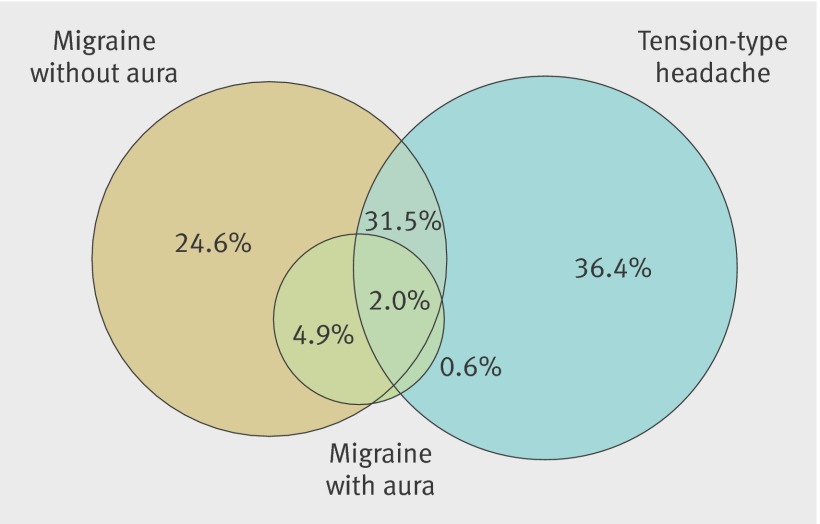

Figure 3 shows the longitudinal stability of the predominant headache subtype for participants who met criteria for either migraine or tension-type headache at least once and participated in four or more interviews across the study period. Of those with migraine or tension-type headache at any interview, 0.6% had migraine with aura and tension-type headache, 24.6% had migraine without aura only, and 36.4% had tension-type headache only as the predominant headache subtype across the entire study period. About 7% met criteria for migraine both with and without aura, and 31.5% had both migraine and tension-type headache.

Fig 3 Combinations of headache subtypes across 30 years among participants who met criteria for migraine (with or without aura) or tension-type headache at ≥1 interview and were interviewed ≥4 times across follow-up (n=346)

Table 4 shows the number of interviews at which participants with either migraine or tension-type headache met criteria for that same predominant subtype across 30 years of follow-up. We did these analyses in those who had participated in four or more interviews across the follow-up period to enable analysis of stability of subtype. Forty-nine per cent of those with migraine (with or without aura) met criteria for migraine only once, 16% continued to meet criteria twice, 15% met criteria at three interviews, and only 21% met criteria at four or more interviews. Most people with migraine with aura (62%) met criteria at only one interview, 20% met them twice, and only 17% met criteria at three interviews. The stability of tension-type headache also tended to diminish over time: 23%, 15%, and 7% met criteria at two, three, and four or more subsequent interviews.

Table 4.

Number of interviews by headache subtypes across 30 years

| Headache subtypes across 30 years | No (%) of interviews with same headache | Total No | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ≥4 | ||

| Migraine with or without aura* | 93 (49.3) | 44 (15.6) | 36 (14.6) | 47 (20.5) | 220 |

| Migraine with aura† | 17 (61.8) | 5 (19.7) | 3 (17.2) | 1(1.3) | 26 |

| Tension-type headache‡ | 130 (55.3) | 65 (23.0) | 32 (14.7) | 17 (7.0) | 244 |

*Respondents with ≥4 interviews who had migraine with or without aura at ≥1 interview (n=220).

†Respondents with ≥4 interviews who had migraine with aura at ≥1 interview (n=26).

‡Respondents with ≥4 interviews who had tension-type headache at ≥1 interview (n=244).

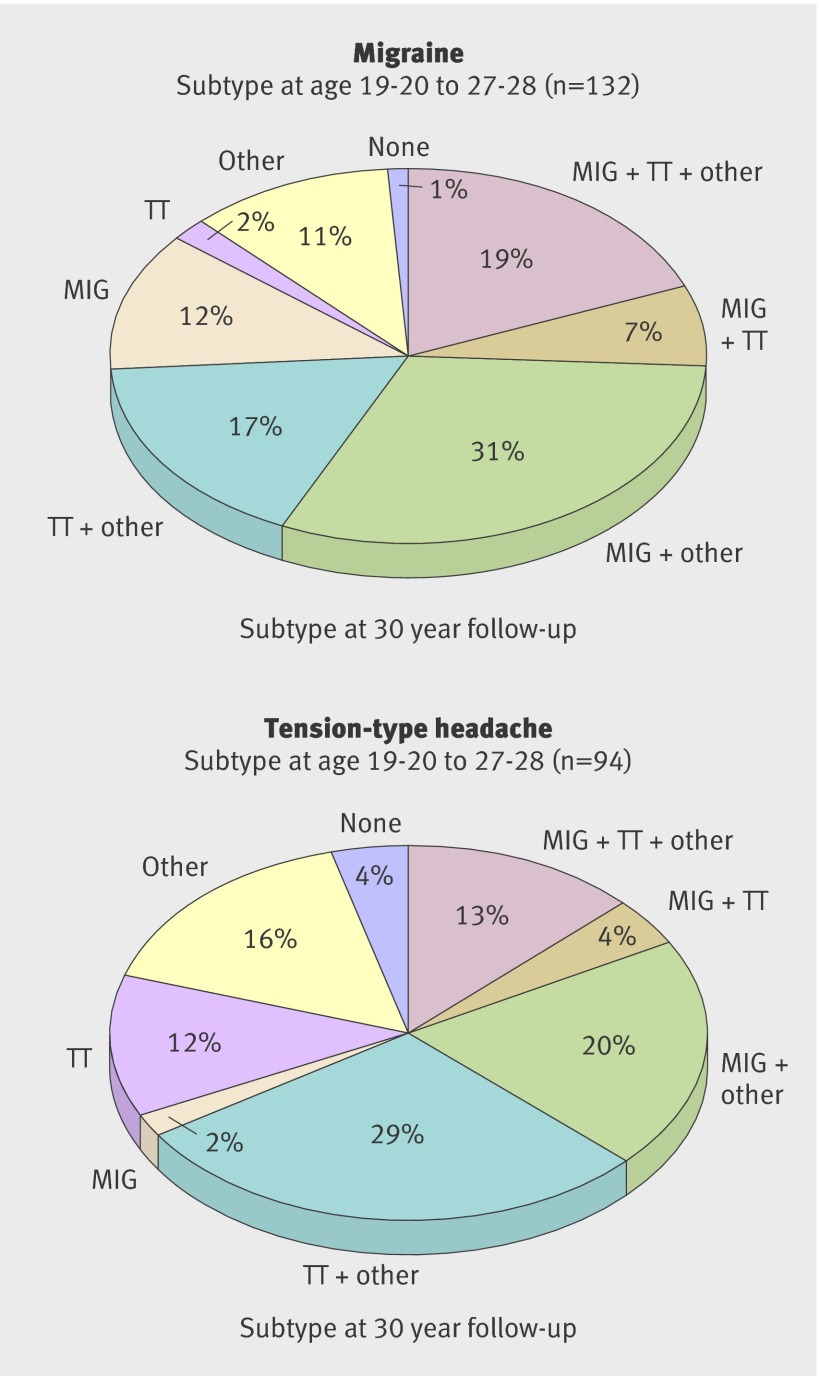

Figure 4 shows the longitudinal stability of migraine and tension-type headache by the predominant headache subtype among participants with either headache subtype at any of the first three interviews (1979, 1981, or 1986) across the 30 year follow-up. Sixty-nine per cent of those with migraine continued to have migraine either alone or in combination with another subtype of headache across the follow-up, whereas 58% of those with tension-type headache continued to manifest that subtype. Twelve per cent of people with migraine and 12% of those with tension-type headache manifested only that subtype. Approximately 19% of those with migraine developed tension-type headache without migraine across the follow-up, and 22% of those with tension-type headache developed migraine alone across the follow-up. Nearly twice as many people with tension-type headache (20%) as with migraine (12%) by the age of 28 ceased to meet criteria for a specific headache subtype during the remainder of the follow-up.

Fig 4 Prospective stability of predominant headache subtype across 30 years among participants who met criteria for migraine (with or without aura; top) or tension-type headache (bottom) at ages 19-20 to 27-28 and were interviewed ≥4 times across follow-up. MIG=migraine with or without aura; TT=tension-type headache

Discussion

The main findings of this prospective follow-up study of a community sample are that, firstly, the cumulative 30 year prevalence rates of subtypes of headache are substantially greater than those derived from cross sectional and retrospective studies of headache; however, most cases were transient and only about 20% continued to have migraine for more than half of the follow-up period. Secondly, the high levels of subjective distress, work impairment, and disability due to headache among people with migraine confirm retrospective research on the dramatic impact of migraine on people’s lives. On average, people with migraine had headaches for one month a year for 24 of the 30 years of the follow-up period. Thirdly, most people tended to have multiple headache subtypes across the lifespan, with no pattern of temporal order of progression. Most (87%) of those with migraine during the first decade of the study met criteria for another subtype or no specific subtype (with or without migraine) during the 20 years of follow-up. Likewise, 84% of those with tension-type headache presented with migraine or another or no specific headache subtype across the follow-up. In fact, only two people manifested migraine with aura alone across the entire follow-up period. Fourthly, we found increasing levels of clinical severity and consequences of headaches across headache subtypes ranging from undiagnosed headache through tension-type headache and migraine without aura to migraine with aura, suggesting an underlying continuum of severity of headache subtypes.

Comparison with other studies

Prevalence

The cumulative rates of migraine and tension-type headache among young adults in this study of 36.0% for migraine without aura, 29.3% for tension-type headache, and 3% for migraine with aura were similar to aggregated international estimates from previous population based studies of headache subtypes.2 4 However, the higher cumulative incidence of migraine from our prospective data compared with previous estimates based on retrospective data highlights the serious problem of under-reporting at follow-up of people with a history of migraine without persistence and the particularly poor retrospective recall of aura.11 14 Finally, the prevalence of migraine tended to peak somewhat earlier in men than in women, with increasing incidence throughout early adult life, confirming the results of prospective studies of children.10 12 14

Impact and clinical correlates

The high levels of subjective distress, work impairment, and disability due to headache among people with migraine support the international evidence that migraine is one of the top 10 leading causes of disability worldwide.26 27 Irrespective of subtype of headache, we found that people with migraine reported an average of 25 days a year with migraine, indicating that they spend nearly one month a year with symptoms of headache. These findings reinforce recent calls for increased support for research on migraine to identify potential targets for prevention and intervention.28

Stability and crossover

One of the most important findings from this study was the substantial magnitude of overlap between the predominant subtypes of headache that occurred at each interview. Nearly all (84%) of the participants with migraine with aura at one or more interviews also reported migraine without aura at another interview, and nearly half of those with migraine without aura or with tension-type headache also had the other subtype longitudinally. Patterns of overlap in headache subtypes were quite similar to the findings of follow-up studies of clinical and population based samples of children and adults.11 12 13 14 A nearly identical pattern of bi-directional crossover between migraine and tension-type headache of 20-25% was reported in a seven year follow-up study of a clinical sample of children and adolescents.13 However, our study is the first to do simultaneous follow-up of all three common subtypes of headache.

Despite the lack of longitudinal stability of the predominant headache subtype and the large proportion of people in whom migraine is time limited, about 21% of those with migraine (with or without aura) and 7% of those with tension-type headache continued to have headaches for more than half of the follow-up period. These findings are remarkably similar to those of the Danish follow-up study that reported remission in about 40-45% of people with previous headaches, intermittent headache in 38%, and chronic severe headache in 20%.11

The substantial overlap across headache subtypes coupled with the gradient of the magnitude of distress, impairment, family history, and service use across the subtypes suggests that migraine and tension-type headache may share some common causative factors. However, evidence for a spectrum of subtypes of headache has been inconsistent.29 30 31 Although some evidence exists for specificity of familial transmission of migraine with and without aura and tension-type headache,32 33 the results of several twin studies show equal heritability of combinations of headache subtypes and symptoms,34 35 36 and others support an underlying continuum of features of headache with different subtypes distinguished by severity rather than by qualitative features.37 38 A clear-cut gradient of severity exists across headache subtypes from migraine with aura to tension-type headache in terms of clinical correlates, severity, treatment, and impact. However, the lack of a unidirectional pattern of onset of tension-type headache and migraine among people who exhibited both subtypes over time suggests that tension-type headache and migraine do not represent progressively more severe manifestations of the same underlying continuum of severity.31

Strengths and limitations

This study is the longest prospective follow-up to date of the major subtypes of headache in a population based sample of young adults as they pass through the peak period of onset and progression of headaches. Other strengths include the use of direct in-person interviews that approximated ICHD-2 criteria for headache syndromes; inclusion of extensive information about non-criterial symptoms, clinical correlates, and impact of headaches; and multiple assessments across the follow-up period rather than only one baseline and one follow-up assessment as used in previous studies.

This study also has several limitations. Firstly, despite the prospective design, we could not capture incident cases that occurred before the age of 18. Secondly, the findings may not be generalisable to other countries owing to the restricted ethnicity and age of this cohort, as well as unique treatment patterns in Switzerland.5 Thirdly, we had to approximate the ICHD-2 criteria at the first two interviews because we included the full criteria only at the last five interviews of the study and no physical or neurological examinations were done in this population based study. Fourthly, we did not classify more than one headache subtype at each interview, so the lack of stability may have been overestimated among people who simultaneously met criteria for both migraine and tension-type headache at several interviews.

Conclusions and implications

This study highlights the importance of prospective research in studying the developmental course and consequences of headache syndromes. The findings have important implications for health policy and for the clinical care, classification, and study of migraine and other headaches. Firstly, our findings clearly show the high prevalence and magnitude of disability associated with these headache syndromes across young to middle adulthood in the general population. Secondly, clinical evaluation and treatment of headache necessarily relies on retrospective recall that has been shown to be highly unreliable. Clinicians should attempt to obtain maximal information on the history, including ancillary information where possible, rather than relying on the clinical presentation in treatment decision making.39 A “person based” rather than a “headache based” approach may provide a more valid depiction of headache for both treatment and studies of the causes of headache. Thirdly, the high frequency of longitudinal crossover of the predominant subtype of headache suggests that the distinction between discrete headache subtypes in the ICHD-2 may not provide an accurate representation of the developmental manifestations of headache in general population samples. The lifetime heterogeneity of expression of headache subtypes is an important impediment to research into the causes of headaches, such as genetic studies that rely on lifetime categorical classification of affected status. Similar to the emerging trend in the classification of mood disorders,40 our data provide evidence for a spectrum of expression of headache characterised by a cluster of core symptoms independent of recurrence, duration, and severity. Research into causes of headache may benefit from a more descriptive empirical approach that captures the protean manifestations of headache across life’s developmental stages.41

What is already known on this topic

Many cross sectional studies have examined the prevalence and correlates of migraine

Few prospective studies of community samples have provided information on the incidence, stability, and course of migraine in adults

What this study adds

Prospective follow-up showed that about 20% of people with migraine develop a chronic course, whereas migraine is time limited in about half of those with migraine in any given year

Substantial longitudinal crossover of the predominant headache subtype occurs across the life course

A gradient of severity across headache subtypes ranges from tension-type headache to migraine with aura in terms of clinical correlates, symptom severity, impairment, family history, and treatment patterns

Contributors: KRM and JA designed the questions covered in the publication and wrote the manuscript. HI, SK, EN, and LC created and reviewed the diagnostic algorithms for headache syndromes. JA and WR designed and supervised the Zurich Cohort Study. HI and KRM developed the questions for the headache section of the interview. LC did the primary statistical analyses. VA-G and AG developed the diagnostic algorithms for many of the diagnostic sections of the interview. AKR, VA-G, AG, and FL contributed to the interpretation of the statistical analyses. All authors have reviewed, edited, and approved the final version. KRM and JA are the guarantors.

Funding: This work was supported by grant 3200-050881.97/1 of the Swiss National Science Foundation and National Institute of Mental Health, Intramural Research Program grant No ZIAMH002807-07 for collaborative analyses of the Zurich Cohort Study. FL is supported by a Rubicon fellowship from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organisations, agencies, or US government.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The Zurich Cohort Study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Zurich.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d5076

References

- 1.Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007;27:193-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:354-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. The epidemiology of migraine. Am J Med 2005;118(suppl 1):3-10S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD, Reed ML. Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States: relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors. JAMA 1992;267:64-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stang P, Von Korff M, Galer BS. Reduced labor force participation among primary care patients with headache. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:296-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:646-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslau N, Davis GC. Migraine, physical health and psychiatric disorder: a prospective epidemiologic study in young adults. J Psychiatr Res 1993;27:211-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jorgensen T, Jensen R. Incidence of primary headache: a Danish epidemiologic follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:1066-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swartz KL, Pratt LA, Armenian HK, Lee LC, Eaton WW. Mental disorders and the incidence of migraine headaches in a community sample: results from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:945-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anttila P, Metsahonkala L, Sillanpaa M. Long-term trends in the incidence of headache in Finnish schoolchildren. Pediatrics 2006;117:e1197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jorgensen T, Jensen R. Prognosis of migraine and tension-type headache: a population-based follow-up study. Neurology 2005;65:580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidetti V, Galli F. Evolution of headache in childhood and adolescence: an 8-year follow-up. Cephalalgia 1998;18:449-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kienbacher C, Wober C, Zesch HE, Hafferl-Gattermayer A, Posch M, Karwautz A, et al. Clinical features, classification and prognosis of migraine and tension-type headache in children and adolescents: a long-term follow-up study. Cephalalgia 2006;26:820-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bille B. A 40-year follow-up of school children with migraine. Cephalalgia 1997;17:488-91, discussion 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder J, Dobler-Mikola A, Angst J. A prospective epidemiological study of psychosomatic and psychiatric syndromes in young adults. Psychother Psychosom 1982;38:128-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derogatis LR. SCL-90: administration, scoring, and procedures manual-1 for the R (revised) version and other instruments of the psychopathology rating scale series. [No publisher listed], 1977.

- 17.Dunn G, Pickles A, Tansella M, Vázquez-Barquero JL. Two-phase epidemiological surveys in psychiatric research. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eich D, Ajdacic-Gross V, Condrau M, Huber H, Gamma A, Angst J, et al. The Zurich Study: participation patterns and Symptom Checklist 90-R scores in six interviews, 1979-99. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2003;418:11-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rössler W, Angst J, Gamma A, Haker H, Stulz N, Merikangas KR, et al. Reappraisal of the interplay between psychosis and depression symptoms in the pathogenesis of psychotic syndromes: results from a twenty-year prospective community study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;261:11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angst J, Gamma A, Neuenschwander M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Eich D, Rössler W, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in the Zurich Cohort Study: a twenty year prospective study. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2005;14:68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual III. American Psychiatric Association Press, 1980.

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders III-R. American Psychiatric Association Press, 1987.

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders IV. American Psychiatric Association Press, 1994.

- 24.Merikangas KR, Angst J, Isler H. Migraine and psychopathology: results of the Zurich cohort study of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990;47:849-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merikangas KR, Whitaker AE, Isler H, Angst J. The Zurich Study: XXIII. Epidemiology of headache syndromes in the Zurich cohort study of young adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994;244:145-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart WF, Wood GC, Razzaghi H, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Work impact of migraine headaches. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:736-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders K, Merikangas K, Low NC, Von Korff M, Kessler RC. Impact of comorbidity on headache-related disability. Neurology 2008;70:538-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro RE, Goadsby PJ. The long drought: the dearth of public funding for headache research. Cephalalgia 2007;27:991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen BK, Olesen J. Epidemiology of migraine and tension-type headache. Curr Opin Neurol 1994;7:264-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipton RB, Cady RK, Stewart WF, Wilks K, Hall C. Diagnostic lessons from the spectrum study. Neurology 2002;58(suppl 6):S27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cady R, Schreiber C, Farmer K, Sheftell F. Primary headaches: a convergence hypothesis. Headache 2002;42:204-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell MB, Ulrich V, Gervil M, Olesen J. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are distinct disorders: a population-based twin survey. Headache 2002;42:332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell MB, Levi N, Kaprio J. Genetics of tension-type headache: a population based twin study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2007;144B:982-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Larsson B, Bille B, Pedersen NL. Genetic influence in headaches: a Swedish twin study. Headache 1995;35:513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ligthart L, Boomsma DI, Martin NG, Stubbe JH, Nyholt DR. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura are not distinct entities: further evidence from a large Dutch population study. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:54-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jorgensen T, Jensen R. Secular changes in health care utilization and work absence for migraine and tension-type headache: a population based study. Eur J Epidemiol 2005;20:1007-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kallela M, Wessman M, Farkkila M, Palotie A, Koskenvuo M, Honkasalo ML, et al. Clinical characteristics of migraine in a population-based twin sample: similarities and differences between migraine with and without aura. Cephalalgia 1999;19:151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honkasalo ML, Kaprio J, Winter T, Heikkila K, Sillanpaa M, Koskenvuo M. Migraine and concomitant symptoms among 8167 adult twin pairs. Headache 1995;35:70-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manzoni GC, Torelli P. Headache classification: criticism and suggestions. Neurol Sci 2004;25(suppl 3):S67-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angst J, Cui L, Swendsen J, Rothen S, Cravchik A, Kessler RC, et al. Major depressive disorder with subthreshold bipolarity in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:1194-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wessman M, Terwindt GM, Kaunisto MA, Palotie A, Ophoff RA. Migraine: a complex genetic disorder. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:521-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]