Abstract

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most frequent biliary tract malignancy. Wide variations in GBC incidence and familial and epidemiological data suggest involvement of a genetic component in its etiopathogenesis. A systematic review of genetic association studies in GBC was performed by applying a meta-analysis approach and systematically reviewing PubMed database using appropriate terms. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were appropriately derived for each gene–disease association using fixed and random effect models. Meta-regression with population size and genotyping method was also performed. Study quality was assessed using a 10-point scoring system designed from published guidelines. Following a review of 44 published manuscripts and one unpublished report, 80 candidate gene variants and 173 polymorphisms were analysed among 1046 cases and 2310 controls. Majority of studies were of intermediate quality. Four polymorphisms with > 3 separate studies were included in the meta-analysis [OGG1 (rs1052133), TP53 (rs1042522), CYP1A1 (rs1048943) and GSTM1 Null polymorphism]. The meta-analysis demonstrated no significant associations of any of the above polymorphisms with GBC susceptibility. To conclude, existing candidate gene studies in GBC susceptibility have so far been insufficient to confirm any association. Future research should focus on a more comprehensive approach utilizing potential gene–gene, gene–environment interactions and high-risk haplotypes.

Keywords: Gallbladder cancer, Polymorphism, Review, Cancer, Meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most frequent biliary tract malignancy and the fifth most common malignant neoplasm of the digestive tract [1]. Despite recent advances in the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal cancers, GBC remains a challenging tumour with a poor overall prognosis. Many of these tumors are not resectable at the time of presentation, and the 5-year survival rate is < 10% in most of the reported series [2]. GBC incidence varies greatly throughout the world, highest being in Native American and South American populations, and people from Poland and Northern India. Between 17000 and 18000 new cases of GBC are diagnosed in India each year, and the annual death rate is almost comparable [3]. The frequency increases with age and reaches to peak during the seventh and eighth decades of life [4]. GBC incidence also shows striking gender bias and affect females 2–3 times more frequently than males [4].

Several epidemiological studies have been conducted to estimate the effects of environmental factors on GBC risk to elucidate the large ethnic variations in risk [5-6]. Yet, no single environmental factor has persistently been linked with GBC risk. It has been observed that Indian migrants to different countries have a higher risk of acquiring GBC as compared to the respective native populations [7]. Thus, the wide geographical, ethnic and interindividual variations observed in the incidence of GBC suggest the involvement of a genetic component in its etiopathogenesis.

The discovery of common genetic polymorphisms in human DNA has led to the publication of a large number of association studies in GBC [8-30]. However, a number of contradictory findings have been reported, and in several cases it has proved difficult to reproduce initial results. Also due to the high false positive associations, the possibility of a true association is well dependent on the quality of the studies concerned [31]. The major flaw with the individual studies is small sample sizes and therefore insufficient statistical power to detect positive associations and incapability to demonstrate the absence of an association. This necessitates the use of meta-analysis to provide an integrative approach by pooling the results of independent analyzes, thereby increasing statistical power and resolution [32-35]. Thus, to get a better insight in the GBC pathogenesis, the present study was undertaken to explore the role of candidate gene polymorphisms in GBC susceptibility by applying a meta-analytical approach and systematically reviewing the available data.

Moreover, to draw a preliminary conclusion, we also carried out a systematic quality review of the published literature on genetic association studies in GBC. This was accomplished by strictly following the various guidelines and checklists that have been published on the conduct of genetic association studies in complex diseases [36-39]. Using the criteria as described by Clark et al [40], we analyzed each publication to highlight the quality issues in the conduct and interpretation of these studies and also to establish if the existing data supports any polymorphism to be conclusively associated with GBC.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Literature Search

Studies were selected by searching PubMed for articles listed from 2000 until March 2011 using the strategy outlined below:

Restriction fragment length polymorphism/ OR genetic polymorphism/ OR single nucleotide polymorphism/ OR DNA polymorphism/ OR genetic variation

Genetic Association/

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism/ OR SNP

Gallbladder cancer/ OR carcinoma of gallbladder/ OR GBC

1 OR 2 OR 3

4 AND 5

Limit 6 to (Human and English language)

Titles and abstracts of articles found were screened, and full texts of articles of interest were evaluated. In addition, articles and bibliographies were hand searched for further suitable papers. We included only original articles that reported associations between GBC and a particular human gene polymorphisms or variability in a case-control or population-based study and were available in English. Case reports and series, reviews and other publications, such as editorials and animal studies were excluded from the analysis.

2.2 Data extraction

From each study, information like: author, year of publication, country of origin, cancer type, ethnicity, number of cases and controls, source of control groups (study design) and genotyping method, was extracted. Ethnic groups were categorized as Asian, European and Mixed. We also checked for HWE in control subjects among all publications.

2.3 Scoring Analysis

The analysis was based on a 10-point scoring sheet adapted from Clark et al [40] which is based on the criteria implemented from published recommendations on the evaluation of the quality of genetic association studies [36-39]. The categories in scoring system used for assessing study quality are summarized in Table 1. The criteria were scored as 1 if present or 0 if absent. Studies were scored as “good” if the score was 8 to 10, “fair” if the score was 5 to 7 and “poor” if the score was <4.

Table 1.

Scoring system for study quality assessment

| Components | Quality Criterion | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | ≥case group, ethnicity matched to cases |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium |

Whether control groups were in HWE |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Case group | Inclusion and exclusion criteria defined, adequate definition of GBC included |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Primer | Primer sequence or a reference provided |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Reproducibility | Described genotyping method to allow replication, validated the accuracy of genotyping |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Blinding | Performed the genotyping whilst blind to case/control status |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Power calculation | Performed a power calculation | Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Statistics | Presented major findings with well described tests of significance |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Corrected statistics | Correction for the false-positive (type I) error |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

| Independent replication | Performed a second, confirmatory study |

Yes = 1 No = 0 |

In some cases, same data was reported in more than one publication, in which case these secondary studies were not included in the meta-analysis. In some studies part of the data had already been reported elsewhere, therefore, only the novel data were included.

2.4 Meta analysis

In the present meta-analysis, we investigated the potential association between those polymorphisms for which there were atleast 3 studies in gallbladder cancer risk. A χ2 test with one degree of freedom was performed in controls to examine deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Analysis between the heterozygote versus wild homozygote, the variant homozygote versus wild homozygote and also in dominant and recessive models was done to estimate cancer risk. For each statistically significant association observed, we estimated the false positive report probability (FPRP) as described by Wacholder et al [41]. Meta-regression analyses were performed by ethnicity, population size, minor allele frequency and genotyping method. A multivariate analysis was performed using the mixed model framework to handle heterogeneity in risks across studies and to adjust genotypic estimates for the effects of ethnicity. This approach can include study effects as either being fixed or random. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated with a χ2-based Q-test among the studies. Heterogeneity was considered significant when p < 0.05. In case of no significant heterogeneity, point estimates and 95% CI (confidence interval) were estimated using the fixed effect model (Mantel-Haenszel), otherwise, random effects model (DerSimonian Laird) was employed. The significance of overall odds ratio (OR) was determined by the Z-test. Publication bias was assessed by Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s linear regression test with p < 0.05 being considered statistically significant [42]. In order to assess the stability of the results, sensitivity analyses were performed. Each study in turn was removed from the total, and the remaining were reanalyzed. Moreover, analysis was also performed, excluding studies whose allele frequencies in controls exhibited significant deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), given that the deviation may denote bias [43]. The type I error rate was set at 0.05. All the p values were two sided and all the statistical tests were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (Version 2.0, BIOSTAT, Englewood, NJ).

2.5 Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium correction

For evaluating impact of HWE-deviated studies on point estimates in genotype-based contrasts, ORs were corrected by using the HWE-predicted genotype counts in the control instead of the observed counts, as suggested by Trikalinos et al [44]; thereafter, they were included in the sensitivity analysis.

2.6 Assessment of cumulative evidence

To each nominally statistically significant association in meta-analysis, we applied the “Venice criteria” [45] to assess the credibility of the evidence. According to this criterion, each meta-analyzed association was graded based on the basis of amount of evidence, extent of replication and protection from bias. Grades of A, B, or C were assigned for each of the above-mentioned criteria. Associations with three A grades assigned were considered to have strong epidemiological credibility; associations with a grade of B but for which all other grades were B or greater were considered to have moderate credibility; any association that received a grade of C were considered to have weak credibility.

3. Results

The PubMed search returned 52 unique articles of which 44 articles met the established inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Overall, these 44 articles investigated 80 candidate genes and 173 different polymorphisms in association with GBC. Fourteen studies investigated the role of gene-gene interactions in GBC susceptibility. Of the 80 genes studied, twenty five were involved in inflammatory pathway, eleven in DNA repair, twenty three in metabolic pathway, fifteen in hormonal pathway, two in signalling pathway and angiogenesis and one each in apoptosis and DNA methylation. One study was on miRNA and GBC association. Thirteen studies reported combination genotypes of polymorphisms and their association with GBC. One unpublished report from our lab analyzed three polymorphisms of ESR1 and one polymorphism of PROGINS.

Validated genotyping methods were used in all studies, which were TaqMan assay (in ten studies), restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP, in thirty three studies) and automated fragment analysis in one study (Table 2). However, blinding of investigators involved in genotyping on the case/control status of the participants was reported in only fourteen studies. Moreover, performing a random double check to detect potential genotyping errors was mentioned in thirty eight studies. Four of the studies did not report information on genotyping [25, 30, 46-47]. Genotype frequencies were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in all of the studies except one [47]. Some studies/polymorphisms were not included in meta-analysis due to redundant information or missing data. All study populations were of mixed gender except in one study, Tsuchiya et al. [48]. All studies were retrospective case-control studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies examining genetic risk factors for GBC susceptibility

| S. No. | Article (author, year) |

Type of study | Gene Polymorphism(s) studied | # of controls |

# of cases |

Ethnicity | Quality Score |

Genotyping method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pramanik, 2011 | Retrospective case control |

KRAS Gln25His | 90 | 60 | Asian | 8 | Sequencing |

| 2 | Xu, 2011 | Retrospective case control |

ABCG8 (rs4148217, rs11887534), CETP (rs708272, rs1800775) and LRPAP1 rs11267919 |

422 | 253 | Asian | 6 | TaqMan |

| 3 | Isomura, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

CYP2C19 (rs4244285, rs4986893) | 566 | 15 | Asian | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 4 | Jiao, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

XPC (rs2228000, rs2228001) | 329 | 334 | Asian | 8 | PCR-RFLP |

| 5 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

ERCC2 (rs1799793, rs13181); MSH2 (rs2303426, rs2303425); OGG1 (rs1052133, rs2072668) |

230 | 230 | Asian | 8 | PCR-RFLP |

| 6 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

CASP8 (rs3834129, rs1045485, rs3769818) | 230 | 230 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 7 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

DNMT3B rs1569686 | 219 | 212 | Asian | 8 | PCR-RFLP |

| 8 | Tsuchiya, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

CYP1A1 (rs4646903, rs1048943); TP53 rs1042522; GSTM1 homozygous null deletion polymorphism |

70 | 57 | Mixed | 6 | TaqMan |

| 9 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

pre-miRNA rs2910164, rs11614913 and rs3746444 |

230 | 230 | Asian | 9 | PCR-RFLP |

| 10 | Meyer, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

AR CAG repeat length [(CAG)n] | 704 | 215 | Asian | 5 | Automated fragment analysis |

| 11 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

TLR2 (Δ22); TLR4 rs4986791 | 257 | 233 | Asian | 9 | PCR-RFLP |

| 12 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

ACE I/D rs4646994 | 260 | 233 | Asian | 9 | PCR-RFLP |

| 13 | Park, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

ESR1 (rs2234693, rs3841686, rs2228480, rs1801132), ESR2 (rs1256049, rs4986938) |

737 | 237 | Asian | 7 | TaqMan |

| 14 | Báez, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

ApoB rs693, ApoE (rs7412, rs429358), CETP rs708272, CYP2C9 (rs1057910, rs1799853), CYP3A4 rs12721627, CYP2E1 (rs2031920, rs6413432) |

70 | 57 | Mixed | 6 | TaqMan |

| 15 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

CYP7A1 (rs3808607, rs3824260) | 200 | 185 | Asian | 9 | PCR-RFLP |

| 16 | Srivastava, 2010 | Retrospective case control |

CR1 (rs2274567, rs12144461) | 200 | 185 | Asian | 9 | PCR-RFLP |

| 17 | Srivastava, 2009 | Retrospective case control |

PTGS2 (rs689466, rs20417, rs5275) | 184 | 167 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 18 | Srivastava, 2009 | Retrospective case control |

OGG1 rs1052133, XRCC1 (rs25487, rs1799782) |

204 | 173 | Asian | 8 | PCR-RFLP |

| 19 | Park, 2009 | Retrospective case control |

COMT (rs4633, rs4818), CYP1A1 (rs2606345, rs1048943), CYP1B1(rs10012, rs1056836), CYP19A1 (rs1065778, rs700518, rs2304463, rs700519, rs1065779, rs4646), HSD3B2 (rs1819698, rs1361530), HSD17B3 (rs2066479), HSD17B1 (rs2830), SHBG (rs6259), SRD5A2 (rs523349) |

737 | 237 | Asian | 8 | TaqMan |

| 20 | Srivastava, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

ABCG8 rs11887534 | 221 | 171 | Asian | 9 | PCR-RFLP |

| 21 | Kimura, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

CYP1A1 (rs4646903, rs1048943), GSTM1 del polymorphism, TP53 rs1042522 |

100 | 43 | European | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 22 | Vishnoi, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

IL1RN 86-bp VNTR and IL1B rs16944 | 166 | 124 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 23 | Zhang, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

MGMT rs12917, RAD23B rs1805335, rs1805329, CCNH rs2266690, XRCC3 rs861539 |

737 | 236 | Asian | 7 | TaqMan |

| 24 | Hsing, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

IL1A (rs17561, rs2856841, rs2071374, rs1800587), IL1B (rs16944, rs1143634, rs1143627), IL4 (rs2243250, rs2243248, rs2070874, rs2243267, rs2243268, rs2243290), IL5 (rs2069812, rs2069807, rs2069818), IL6 (rs1800795, rs1800796, rs1800797), IL8 (rs4073, rs2227307, rs2227306), IL10 (rs3024496, rs3024491, rs1800871, rs1800872, rs1800896), IL13 (rs1800925, rs1295686, rs20541), IL16 (rs859, rs11325), IL8RA (rs2234671), IL8RB (rs1126579, rs1126580, rs2230054), PPARD (rs2016520), PPARG (rs2938392, rs3856806), RNASEL (rs486907, rs11072), SOD2 rs4880, MPO (rs2333227, rs2243828), NOS2 (rs944722, rs2297518), NOS3 (rs1799983, rs1007311), TGFB1 (rs1800469, rs1982073), TNF (rs1799964, rs1800630, rs1799724, rs1800750, rs1800629, rs361525, rs1800610), VCAM1 (rs1041163, rs3176878, rs3176879), VEGF rs3025039 |

737 | 237 | Asian | 8 | TaqMan |

| 25 | Vishnoi, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

EGF rs4444903, TGFB1 rs1800469 | 190 | 126 | Asian | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 26 | Srivastava, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

CCR5 rs333 | 210 | 144 | Asian | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 27 | Chang, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

PPARG rs3856806, PPARD rs2016520, RXRA (rs1536475, rs1805343), RXRB (rs2744537, rs2076310) and INS rs689 |

737 | 237 | Asian | 8 | TaqMan |

| 28 | Andreotti, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

ApoB (rs676210, rs673548, rs520354, rs1367117), ApoE rs440446, LDLR (rs1003723, rs5930, rs5927, rs6413504, rs14158), LPL rs263, ALOX5 rs2029253 |

730 | 235 | Asian | 7 | TaqMan |

| 29 | Pandey, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

CYP1A1 rs4646903 | 171 | 142 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 30 | Srivastava, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

CYP7A1 rs3808607 | 200 | 141 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 31 | Huang, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

XRCC1 (rs1799782, rs25489, rs25487), APEX1 rs3136820, OGG1 rs1052133 |

737 | 237 | Asian | 8 | TaqMan |

| 32 | Srivastava, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

MTHFR rs1801133 | 210 | 146 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 33 | Srivastava, 2008 | Retrospective case control |

CCKAR rs1800857 | 190 | 139 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 34 | Vishnoi, 2007 | Retrospective case control |

TNFA rs1800629, IL6 rs1800795 | 200 | 124 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 35 | Pandey, 2007 | Retrospective case control |

ApoB rs693 and rs17240441 | 232 | 123 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 36 | Tsuchiya, 2007 | Retrospective case control |

CYP1A1 (rs4646903, rs1048943), GSTM1 homozygous null deletion polymorphism, TP53 rs1042522 |

178 | 54 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 37 | Jiao, 2007 | Retrospective case control |

OGG1 rs1052133 | 209 | 204 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 38 | Pandey, 2007 | Retrospective case control |

NAT2 (rs1799929, rs1799930, rs1799931) | 147 | 124 | Asian | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 39 | Pandey, 2006 | Retrospective case control |

LRPAP1 rs11267919 | 208 | 129 | Asian | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 40 | Pandey, 2006 | Retrospective case control |

GSTM1 and GSTT1 homozygous null deletion polymorphism, GSTP1 rs1695, GSTM3 rs1799735 |

201 | 106 | Asian | 6 | PCR-RFLP |

| 41 | Hou, 2006 | Retrospective case control |

CYP17 rs743572 | 818 | 254 | Asian | 7 | PCR-RFLP |

| 42 | Sakoda, 2006 | Retrospective case control |

PTGS2 (rs20420, rs5277, rs20432, rs4648276, rs5273, rs4648291, rs5275, rs689470) |

737 | 237 | Asian | 8 | TaqMan |

| 43 | Singh, 2004 | Retrospective case control |

ApoB rs693 | 137 | 153 | Asian | 4 | PCR-RFLP |

| 44 | Tsuchiya, 2002 | Retrospective case control |

CYP1A1 (rs4646903, rs1048943) | 104 | 52 | Asian | 5 | PCR-RFLP |

| 45 | Unpublished report |

Retrospective case control |

ESR1 (rs2234693, rs9340799, rs1801132), PROGINS 306 bp insertion (rs10428388) |

220 | 243 | Asian | - | PCR-RFLP |

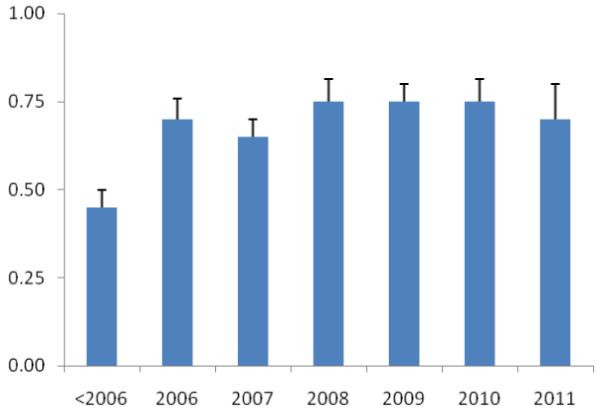

The quality of studies was generally mediocre; mean quality score was 7.11/10 (range 4 to 9). Sixteen studies were scored as “good”, 27 were “mediocre,” while only one was of “poor” quality. Primarily, studies were deficient in the areas of blinding, reproducibility, power calculations and independent replication. The studies were also divided into year of publication. The average score of genetic association studies in GBC, expressed as a percentage of total possible scores from 0 to 1, with standard error of the mean was plotted against the year of publication. There was an evidence of a trend towards improvement over time with R2=0.69 (logarithmic trendline).

3.1 Meta-analysis of the association between the studied polymorphisms and GBC

The summary of meta-analysis for the candidate gene polymorphisms with GBC is shown in Table 3. Some of the studies were excluded from analysis due to limited available data (Table S1). The overall OR of the association between the variant allele of all the polymorphisms analyzed and GBC was 1.14 (95% CI = 1.06–1.24, P = 0.001). Among the candidate gene studies, XPC (rs2228000), ERCC2 (rs1799793), MSH2 (rs2303426), OGG1 (rs2072668), XRCC1 (rs25487), CR1 (rs2274567), IL-1RN, PTGS2 (rs689466), IL1B (rs16944), EGF (rs4444903), KRAS Gln25His, NAT2, GSTT1, ESR1 (rs9340799) and CYP7A1 (rs3808607) showed significant association with GBC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association studies of candidate gene polymorphisms and GBC risk

| Article (author, year) |

Gene | Variant | Risk allele |

Gene Polymorphism(s) studied |

Total cases |

Total controls |

OR (95% CI)a |

No of studies |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA repair pathway genes | |||||||||

| Jiao, 2010 | XPC | rs2228000 | T | Ala499Val | 334 | 329 | 1.93 (1.04-3.55) |

1 | [54] |

| Jiao, 2010 | XPC | rs2228001 | C | Lys939Gln | 334 | 329 | 1.41 (0.85-2.36) |

1 | [54] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

ERCC2 | rs1799793 | A | Asp312Asn | 230 | 230 | 2.10 (1.10-4.01) |

1 | [49] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

ERCC2 | rs13181 | T | Lys751Gln | 230 | 230 | 1.50 (0.85-2.64) |

1 | [49] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

MSH2 | rs2303426 | C | IVS1+9G>C | 230 | 230 | 1.80 (1.07-3.04) |

1 | [49] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

MSH2 | rs2303425 | C | −118T>C | 230 | 230 | 1.40 (0.49-3.96) |

1 | [49] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

OGG1 | rs2072668 | G | 748−15C>G | 230 | 230 | 2.00 (1.17-3.48) |

1 | [49] |

| Srivastava, 2010, Huang, 2008, Jiao 2007 |

OGG1 | rs1052133 | G | Ser326Cys | 671 | 1176 | 1.76 (0.63-4.91) |

3 | [49-51] |

| Tsuchiya, 2010, Kimura, 2008, Tsuchiya, 2007 |

TP53 | rs1042522 | G | Pro72Arg | 154 | 348 | 1.28 (0.68-2.42) |

3 | [48, 52-53] |

| Srivastava, 2009, Huang, 2008 |

XRCC1 | rs1799782 | T | Arg194Trp | 410 | 941 | 0.94 (0.58-1.54) |

2 | [14, 50] |

| Srivastava, 2009, Huang, 2008 |

XRCC1 | rs25487 | A | Arg399Gln | 410 | 941 | 0.59 (0.38-0.93) |

2 | [14, 50] |

| Huang, 2008 | APEX1 | rs3136820 | T | Asp148Glu | 237 | 737 | 0.79 (0.51-1.22) |

1 | [50] |

| Zhang, 2008 | RAD23B | rs1805335 | G | IVS5−15A>G | 236 | 737 | 1.40 (0.71-2.76) |

1 | [83] |

| Zhang, 2008 | RAD23B | rs1805329 | T | EX7+65C>T | 236 | 737 | 0.97 (0.41-2.30) |

1 | [83] |

| Hormone pathway genes | |||||||||

| Srivastava, 2008 |

CCKAR | rs1800857 | C | IVS1−5T>C | 139 | 190 | 1.05 (0.55-2.01) |

1 | [12] |

| Park, 2010, unpublished report |

ESR1 | rs2234693 | T | IVS1−397T>C | 480 | 957 | 1.46 (1.00-2.12) |

2 | [55] |

| Park, 2010 | ESR1 | rs3841686 | T | IVS5−34−>T | 237 | 737 | 0.80 (0.49-1.29) |

1 | [55] |

| Park, 2010 | ESR1 | rs2228480 | G | Ex8+229G>A | 237 | 737 | 0.70 (0.32-1.54) |

1 | [55] |

| Park, 2010, unpublished report |

ESR1 | rs1801132 | G | Ex4−122G>C | 480 | 957 | 0.88 (0.60-1.29) |

2 | [55] |

| unpublished report |

ESR1 | rs9340799 | G | IVS1−351A>G | 243 | 220 | 2.50 (1.29-4.85) |

1 | - |

| Park, 2010 | ESR2 | rs1256049 | A | Val328Val | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.61-1.63) |

1 | [55] |

| Meyer, 2010 | AR | - | - | (CAG)n | 215 | 704 | 0.99 (0.68-1.43) |

1 | [84] |

| Park, 2009 | COMT | rs4633 | T | His62His | 237 | 737 | 0.90 (0.49-1.66) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | COMT | rs4818 | C | Leu136Leu | 237 | 737 | 1.20 (0.74-1.95) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP1A1 | rs2606345 | T | IVS1+606G>T | 237 | 737 | 2.00 (1.29-3.09) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP1B1 | rs10012 | C | Arg48Gly | 237 | 737 | 0.90 (0.41-1.96) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP19A1 | rs1065778 | G | IVS4−76A>G | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.65-1.54) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP19A1 | rs700518 | A | Val80Val | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.67-1.49) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP19A1 | rs2304463 | T | IVS7−106T>G | 237 | 737 | 0.90 (0.59-1.37) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP19A1 | rs700519 | T | Arg264Cys | 237 | 737 | 1.10 (0.48-2.51) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP19A1 | rs1065779 | T | IVS9−53G>T | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.65-1.54) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | CYP19A1 | rs4646 | T | Ex11+410G>T | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.59-1.68) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | HSD3B2 | rs1819698 | T | Ex4−133C>T | 237 | 737 | 1.40 (0.79-2.47) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | HSD3B2 | rs1361530 | G | Ex4−88C>G | 237 | 737 | 1.50 (0.82-2.76) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | HSD17B3 | rs2066479 | A | Gly289Arg | 237 | 737 | 0.60 (0.32-1.13) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | HSD17B1 | rs2830 | A | Ex1−486G>A | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.69-1.58) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | SHBG | rs6259 | A | Ex8+6G>A | 237 | 737 | 1.900 (0.80-4.51) |

1 | [18] |

| Park, 2009 | SRD5A2 | rs523349 | G | Ex1−17G>C | 237 | 737 | 1.00 (0.69-1.45) |

1 | [18] |

| Chang, 2008 | RXR-α | rs1536475 | A | IVS6+70A>G | 237 | 737 | 0.65 (0.32-1.32) |

1 | [85] |

| Chang, 2008 | RXR-α | rs1805343 | A | IVS1−27A>G | 237 | 737 | 0.80 (0.49-1.31) |

1 | [85] |

| Chang, 2008 | RXR-β | rs2744537 | T | G392T | 237 | 737 | 0.82 (0.45-1.51) |

1 | [85] |

| Chang, 2008 | RXR-β | rs2076310 | C | C51T | 237 | 737 | 1.30 (0.83-2.04) |

1 | [85] |

| Chang, 2008 | INS | rs689 | A | A-6T | 237 | 737 | 0.96 (0.57-1.62) |

1 | [85] |

| Chang, 2008b |

PPARD | rs2016520 | A | Ex4+15C>T | 237 | 737 | 1.09 (0.63-1.89) |

1 | [85] |

| Chang, 2008b |

PPARG | rs3856806 | T | His477His | 237 | 737 | 1.25 (0.67-2.33) |

1 | [85] |

| Inflammatory pathway genes | |||||||||

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CR1 | rs2274567 | G | His1208Arg | 185 | 200 | 1.94 (1.10-3.41) |

1 | [9] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CR1 | rs12144461 | T | Intron 27, HindIII | 185 | 200 | 1.27 (0.75-2.14) |

1 | [9] |

| Vishnoi, 2008 |

IL1RN | - | - | 86-bp VNTR | 124 | 166 | 3.25 (1.23-8.58) |

1 | [26] |

| Srivastava, 2009 |

PTGS2 | rs689466 | A | −1195G>A | 167 | 184 | 2.98 (1.00-8.89) |

1 | [17] |

| Srivastava, 2009 |

PTGS2 | rs20417 | C | −765G>C | 167 | 184 | 1.06 (0.39-2.85) |

1 | [17] |

| Srivastava, 2009, Sakoda, 2006 |

PTGS2 | rs5275 | C | +8473T>C | 404 | 921 | 1.28 (0.78-2.14) |

2 | [17, 86] |

| Hsing, 2008, Vishnoi, 2008 |

IL1B | rs16944 | C | −1060T>C | 361 | 903 | 3.36 (1.52-7.43) |

2 | [20, 26] |

| Hsing, 2008 | IL10 | rs1800871 | T | −7334T>C | 237 | 737 | 0.74 (0.44-1.24) |

1 | [20] |

| Hsing, 2008 | IL10 | rs1800872 | A | −6653A>C | 237 | 737 | 0.76 (0.45-1.27) |

1 | [20] |

| Vishnoi, 2008 |

EGF | rs4444903 | A | +61A>G | 126 | 190 | 2.22 (1.19-4.15) |

1 | [28] |

| Vishnoi, 2008, Hsing, 2008 |

TGFβ1 | rs1800469 | T | −509C>T | 361 | 937 | 1.47 (0.72-3.01) |

2 | [20, 28] |

| Vishnoi, 2007, Hsing, 2008 |

TNFα | rs1800629 | A | −308G>A | 361 | 937 | 1.47 (0.41-5.28) |

2 | [20, 27] |

| Vishnoi, 2007, Hsing, 2008 |

IL6 | rs1800795 | C | −236C>G | 361 | 937 | 0.60 (0.06-5.95) |

2 | [20, 27] |

| Metabolic pathway genes | |||||||||

| Srivastava, 2008 |

MTHFR | rs1801133 | T | Ala222Val | 146 | 210 | 1.08 (0.32-3.69) |

1 | [13] |

| Pandey, 2007 |

APOB | rs17240441 | - | 35_43del9 | 123 | 232 | 3.30 (0.81-13.51) |

1 | [25] |

| Pandey, 2007 |

NAT2 | rs1799929, rs1799930, rs1799931 |

T, A, A |

NAT2*5A, NAT2*6B, NAT2*7A |

124 | 147 | 3.40 (1.98-5.84) |

1 | [24] |

| Pandey, 2006 |

GSTT1 | - | - | null polymorphism |

106 | 201 | 0.24 (0.1-0.59) |

1 | [23] |

| Pandey, 2006 |

GSTP1 | rs1695 | A | Ile105Val | 106 | 201 | 2.10 (0.83-5.30) |

1 | [23] |

| Hou, 2006 | CYP17 | rs743572 | A | Ex1+27T>C | 254 | 818 | 1.40 (0.92-2.14) |

1 | [78] |

| Tsuchiya, 2010, Kimura, 2008, Pandey, 2006, Tsuchiya, 2007 |

GSTM1 | - | - | null polymorphism |

260 | 549 | 1.08 (0.73-1.60) |

4 | [23, 48, 52-53] |

| Tsuchiya, 2010, Kimura, 2008, Pandey, 2008, Tsuchiya, 2007 |

CYP1A1 | rs4646903 | C | CYP1A1*2A | 296 | 519 | 1.28 (0.49-3.38) |

4 | [21, 48, 52-53] |

| Tsuchiya, 2010, Park, 2009, Kimura, 2008, Tsuchiya, 2007 |

CYP1A1 | rs1048943 | G | Ile462Val (*2C) | 391 | 1085 | 0.72 (0.42-1.22) |

4 | [18, 48, 52-53] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

LDLR | rs5930 | A | EX10+55G>A | 235 | 730 | 1.10 (0.70-1.73) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

LDLR | rs6413504 | G | IVS17−42A>G | 235 | 730 | 0.81 (0.45-1.46) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

LDLR | rs14158 | A | EX18+88G>A | 235 | 730 | 1.12 (0.72-1.74) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

LPL | rs263 | T | IVS5−540C>T | 235 | 730 | 0.69 (0.31-1.53) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

ALOX5 | rs2029253 | A | IVS3+100G>A | 235 | 730 | 1.16 (0.74-1.83) |

1 | [66] |

| Pandey, 2007, Báez, 2010 |

ApoB | rs693 | T | Thr2515Thr | 180 | 302 | 0.37 (0.15-0.89) |

2 | [25, 64] |

| Xu, 2011, Srivastava, 2008 |

ABCG8 | rs11887534 | C | Asp19His | 424 | 643 | 1.63 (0.10-26.53) |

2 | [15, 65] |

| Xu, 2011, Báez, 2010 |

CETP | rs708272 | T | TaqIB | 310 | 492 | 1.06 (0.55-2.04) |

2 | [64-65] |

| Xu, 2011 | CETP | rs1800775 | C | −629C>A | 253 | 422 | 1.17 (0.75-1.83) |

1 | [65] |

| Xu, 2011, Pandey, 2006 |

LRPAP1 | rs11267919 | - | 752-177_752- 176ins37 |

382 | 630 | 1.08 (0.71-1.66) |

2 | [22, 65] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CYP7A1 | rs3808607 | A | −204 A>C | 185 | 200 | 2.05 (1.12-3.76) |

1 | [56] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CYP7A1 | rs3824260 | C | −469 T>C | 185 | 200 | 0.86 (0.49-1.54) |

1 | [56] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

ApoB | rs676210 | C | Pro2739Leu | 235 | 730 | 1.15 (0.64-2.07) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

ApoB | rs673548 | C | IVS23−79T>C | 235 | 730 | 0.97 (0.52-1.81) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

ApoB | rs520354 | T | IVS6+360C>T | 235 | 730 | 1.51 (0.63-3.61) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

ApoB | rs1367117 | T | Thr98Ile | 235 | 730 | 2.54 (0.97-6.68) |

1 | [66] |

| Andreotti, 2008 |

ApoE | rs440446 | G | IVS1+69C>G | 235 | 730 | 1.32 (0.83-2.10) |

1 | [66] |

| Isomura, 2010 |

CYP2C19 | rs4244285, rs4986893 |

A, A | CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3 |

15 | 566 | 1.16 (0.39-3.51) |

1 | [30] |

| Other genes | |||||||||

| Pramanik, 2011 |

KRAS | - | T | Gln25His | 90 | 60 | 2.81 (1.42-5.56) |

1 | [57] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

hsa-miR-

146a |

rs2910164 | C | G>C | 230 | 230 | 2.40 (0.81-7.10) |

1 | [60] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

hsa-mir-

196a2 |

rs11614913 | T | C>T | 230 | 230 | 0.94 (0.46-1.91) |

1 | [60] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

hsa-mir-

499 |

rs3746444 | C | T>C | 230 | 230 | 1.50 (0.71-3.16) |

1 | [60] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

ACE I/D | rs4646994 | - | 289 bp del polymorphism |

233 | 260 | 1.38 (0.73-2.60) |

1 | [62] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

DNMT3B | rs1569686 | G | −579 G>T | 212 | 219 | 1.56 (0.84-2.90) |

1 | [61] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

TLR2 | - | - | −196_174del | 233 | 257 | 2.14 (0.56-8.14) |

1 | [58] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

TLR4 | rs4986791 | T | Thr399Ile | 233 | 257 | 7.57 (0.83-69.16) |

1 | [58] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CASP8 | rs3834129 | N/A | −652 6N ins/del | 230 | 230 | 0.42 (0.20-0.89) |

1 | [59] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CASP8 | rs1045485 | C | Asp302His | 230 | 230 | 0.95 (0.06-15.27) |

1 | [59] |

| Srivastava, 2010 |

CASP8 | rs3769818 | A | IVS12−19 G > A | 230 | 230 | 0.83 (0.18-3.86) |

1 | [59] |

homozygous variant genotype vs. homozygous wild genotype.

reported by Hsing et al [20] also in same set of samples.

3.2.1 DNA repair pathway genes

The OGG1 Ser326Cys polymorphism was analyzed in 3 studies [49-51] with 671 cases and 1176 controls and was found to be associated with increased risk of GBC although the association was not statistically significant (OR=1.76, 95% CI=0.63-4.91, CysCys vs. SerSer; Table 4). Significant heterogeneity was observed (Q=8.748, P=0.013, I2=77.14%, CC vs. SS; Table 4). Three studies comprising 154 cases and 348 controls evaluated a possible association between TP53 rs1042522 polymorphism and risk of GBC [48, 52-53]. No association was observed (OR=1.28, 95% CI=0.68-2.42, P=0.441; Table 4) and there was no heterogeneity (Q=0.623, P=0.732, I2=0%). In a study of 334 GBC cases, Jiao et al. [54] examined the association of polymorphisms in XPC gene, involved in nucleotide excision repair pathway (NER). Individuals with the T allele of XPC Ala499Val polymorphism possessed greater risk of GBC (OR=1.40). Srivastava et al. [49] found significant association with the variant alleles of ERCC2, MSH2 and OGG1 gene polymorphisms. No significant associations were found with other genes involved with DNA repair pathway.

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of candidate gene polymorphisms in different genotype models and GBC association

| Gene & rs number | Polymorphism | No. of studies |

Test of association | Test of heterogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | Model | Q | Phet | I2 | |||

| OGG1 (rs1052133) | C vs. S | 3 | 0.87 | 0.53-1.44 | 0.600 | Random | 21.791 | <0.001 | 90.822 |

| CC+CS vs. SS | 3 | 0.97 | 0.68-1.39 | 0.891 | Random | 6.413 | 0.046 | 67.442 | |

| CC vs. CS+SS | 3 | 1.62 | 0.80-3.30 | 0.180 | Random | 9.185 | 0.010 | 78.226 | |

| CC v. SS | 3 | 1.76 | 0.63-4.91 | 0.277 | Random | 8.748 | 0.013 | 77.139 | |

| TP53 (rs1042522) | R vs. P | 3 | 1.38 | 1.02-1.87 | 0.035 | Fixed | 5.268 | 0.072 | 62.037 |

| RR+RP vs. PP | 3 | 1.65 | 0.74-3.72 | 0.223 | Random | 7.822 | 0.020 | 74.432 | |

| RR vs. RP+PP | 3 | 1.27 | 0.71-2.72 | 0.423 | Fixed | 0.921 | 0.64 | 0 | |

| RR vs. PP | 3 | 1.28 | 0.68-2.42 | 0.441 | Fixed | 0.623 | 0.732 | 0 | |

| GSTM1 a | Null vs. non null | 3 | 1.08 | 0.73-1.60 | 0.697 | Fixed | 0.369 | 0.831 | 0 |

| CYP1A1 (rs1048943)a | V vs. I | 3 | 0.89 | 0.73-1.10 | 0.279 | Fixed | 4.311 | 0.116 | 53.605 |

| VV+VI vs. II | 3 | 0.89 | 0.69-1.15 | 0.366 | Fixed | 5.237 | 0.073 | 61.814 | |

| VV vs. VI+II | 3 | 0.78 | 0.46-1.32 | 0.359 | Fixed | 0.267 | 0.875 | 0 | |

| VV vs. II | 3 | 0.72 | 0.42-1.22 | 0.221 | Fixed | 1.009 | 0.604 | 0 | |

data from Kimura et al [52] not available.

In the case of significant heterogeneity (Phet<0.05), ORs were calculated using random effect model, otherwise fixed-effects model was used.

3.2.2 Hormone pathway genes

Five polymorphisms of ESR1 gene have been investigated relative to the risk of GBC. Two of the studies, including one unpublished report from our lab, looked at ESR1 IVS1-397T>C and Ex4-122G>C polymorphisms using 480 cases and 957 controls [55]. They found no significant association of these polymorphisms with GBC risk (OR=1.46, 95% CI=1.00-2.12 and OR=0.88, 95% CI=0.60-1.29, respectively; Table 3). However, one unpublished report from our lab analyzing potential association of ESR1 IVS1-351A>G polymorphism and GBC risk found 2.5 fold increased risk of GBC in multivariable analysis (95% CI=1.29-4.85; Table 3). None of the polymorphisms in other genes analyzed in hormone pathway were found to be significantly associated with GBC risk in published reports (Table 3).

3.2.3 Inflammatory pathway genes

Eight different studies examined a total of 73 polymorphisms in twenty five genes involved in inflammatory pathways. Due to limited information, we were able to incorporate only 18 polymorphisms in our analysis. The IL1B rs16944 polymorphism was investigated in two studies, of which only Vishnoi et al. [26] found a significant association. Srivastava et al. [17] found GA+AA carriers of PTGS2 −1195G>A polymorphism were significantly associated with increased risk of GBC (OR=2.12). Other polymorphisms of inflammatory pathway which were found to be associated with GBC were CR1 His1208Arg, IL1RN 86-bp VNTR and EGF +61A>G. Hsing et al. [20], in a population of 237 GBC patients found that the T allele (CT+TT genotype) of the VEGF rs3025039 polymorphism conferred 0.70 fold reduced risk of GBC (95%, CI= 0.50–0.97). This remained true after adjustment for smoking, drinking, BMI, gallstones, as well as correction for multiple comparisons. Also IL10 TC genotype of −7334T>C polymorphism was found to be associated with a reduced risk of gallbladder cancer (OR=0.69) [20].

3.2.4 Metabolic pathway genes

Only two polymorphisms reported by Pandey et al. [24] (NAT2) and Srivastava et al. [56] (CYP7A1 −204 A>C) reported significant association with GBC in multivariable analysis (OR= 3.40 and 2.05, respectively). The association of CYP1A1 rs1048943 polymorphism and GBC risk was evaluated in 4 studies that comprised 391 cases and 1085 controls [18, 48, 52-53]. No association between the risk for GBC and CYP1A1 rs1048943 polymorphism was observed (OR=0.72, 95% CI=0.42-1.22, P=0.221; Table 4). There was no heterogeneity observed among the studies (Q=4.311, P=0.116, I2=53.6%). Four studies examined the relationship between GSTM1 polymorphisms and risk of GBC in 260 cases and 549 controls [23, 48, 52-53]. Null allele of GSTM1 did not cause any increase in the risk for GBC (OR=1.08, 95% CI=0.73-1.60,; Table 4). No heterogeneity was found (Q=0.369, P=0.831, I2=0%). Four studies evaluated the relationship between CYP1A1 rs4646903 polymorphism and GBC risk [21, 48, 52-53]. But due to limited data availability, meta-analysis could not be performed. None of the remaining polymorphisms investigated were found to be significantly associated with GBC.

3.2.5 Other genes

The angiogenesis pathway gene KRAS Gln25His polymorphism was significantly associated with GBC risk (OR= 2.81; P=0.003) in a multivariable study from Eastern India [57]. The polymorphisms in other genes such as angiogenesis pathway (ACE), signaling (TLR), miRNA, apoptosis (CASP8) or methylation (DNMT3B) pathway were significantly associated with GBC (additive model) [58-62].

3.3 Gene-Gene Interactions

There were fourteen studies that investigated gene-gene interactions and their association with GBC. The combinations studied were mostly between genes of metabolic, DNA repair, inflammatory and hormone pathways. Srivastava et al. [63] performed Classification and Regression Tree Analysis (CART) and Grade of Membership (GoM) analysis on 16 polymorphisms in 8 genes involved in DNA repair, apoptotic and inflammatory pathways to identify combinations of alleles contributing to GBC risk. The CART analysis revealed OGG1 Ser326Cys, and OGG1 IVS4-15C>G polymorphisms as the best polymorphic signature for discriminating between cases and controls. GoM analysis categorized the data into low risk (controls) and high risk groups (patients) on the basis of risk alleles. Baez et al. [64] investigated the combination of “at-risk” genotypes of the APOB rs693 and CETP rs708272 polymorphisms with GBC risk. They found that compared with all remaining combinations, patients with [C/C (apoB) +T/T (CETP)] genotypes had an elevated risk for GBC (age adjusted OR= 4.75; 95% CI= 1.16 -19.4). Xu et al. [65] found that the carriers of the ABCG8 (rs4148217 and rs11887534) C-C haplotype had >4 fold greater risk of GBC (95% CI=1.71-10.1). Srivastava et al. [56] found that the C-T and C-C haplotype frequencies of the CYP7A1 gene were significantly higher in GBC group compared to healthy controls and imposed higher risk for the disease (ORs= 1.84 and 3.10, respectively). They hypothesized that the altered gallbladder bile composition to lithogenic profile due to CYP7A1 −204 A>C and −469 T>C promoter polymorphisms may impair fatty acid metabolism and decrease hepatic canalicular bile acid transport, causing accumulation of free radicals and other toxic products by lipid peroxidation, leading to GBC susceptibility. Srivastava et al. [17] found that compared with the most common haplotype of the PTGS2 gene, G−1195G−765T+8473, the A−1195G−765T+8473 haplotype was associated with a significantly increased risk of GBC (OR= 2.20; 95%CI= 1.1–4.4). Srivastava et al. [49] performed a correlation and regression tree analysis (CART) to identify risk sets of polymorphisms in OGG1, MSH2 and ERCC2 genes. Compared with the low-risk group combining terminal nodes with a case ratio <45%, the medium-risk (case ratio between 45%and 55%) and high-risk groups (case ratio >55%) were both associated with a significantly increased GBC risk (ORs = 7.6 and 1.7, respectively; Ptrend <0.001). Hsing et al. [20] found that none of the 5 inferred haplotypes involving three separate SNPs in the IL8RB gene (Ex3+811C>T, Ex3+1235T>C, Ex3−1010G>A) were associated with GBC risk. None of the haplotypes for LDLR IVS9−30C>T-EX10+55G>A-EX15−80G>A-IVS17−42A>G-EX18+88G>A, APOB IVS6+360C>T-EX4+56C>T and APOB EX26-3573T>C-IVS23-79T>C were found to be significantly associated with GBC risk in a study by Andreotti et al. [66]. Also, no associations for any of six major haplotypes for ESR1 gene were found relative to the most common haplotype with GBC risk in a study by Park et al [55].

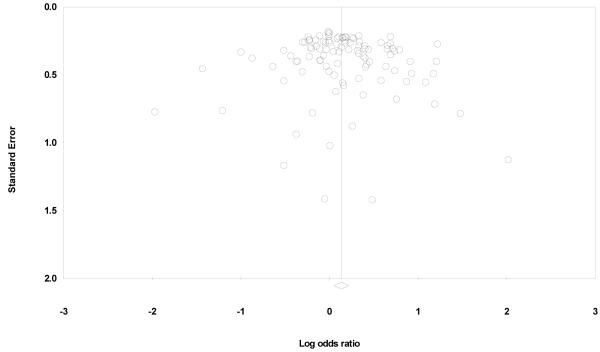

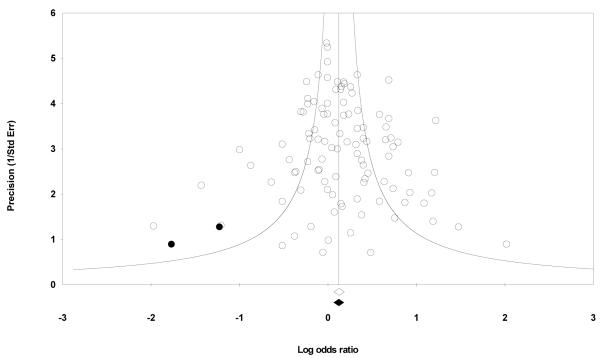

Meta-analysis was also performed for polymorphisms with more than 2 studies which involved the OGG1 Ser326Cys, TP53 Pro72Arg, GSTM1 null and CYP1A1 Ile462val polymorphisms (Table 4 and Fig. 2). Meta-analysis of TP53 Pro72Arg polymorphism showed significant association at the allelic level (OR= 1.38). Based on Venice criteria, for “amount of evidence”, this association was graded as C (n<100 variant Pro allele in cases and controls combined), grade C for “replication consistency” due to high between-study inconsistency (I2 >50%) and grade C for “protection from bias”. Thus, TP53 Pro72Arg polymorphism would be graded as having weak credibility according to the Venice criteria. Rest of the studied polymorphisms revealed no association with GBC at genotypic level and allelic level or under recessive model and dominant models (Table 4; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ORs and 95% CIs of individual studies for the association between the OGG1 (rs1052133) polymorphism Cys allele, TP53 (rs1042522) polymorphism Arg allele, GSTM1 null polymorphism and CYP1A1 (rs1048943) Val allele and GBC. The size of the box is proportional to the weight of the study. CI, confidence interval

3.4 Meta-regression

We performed the regression analysis for three predefined potential sources of heterogeneity, the ethnic background, study size, and also genotyping methods adding single covariates at a time in a series of univariate models. Dummy variables were created for sample size (0 for < 200 cases) vs. (1 for >200 cases) and for genotyping methods as TaqMan (1), otherwise (0); and PCR-RFLP (1), otherwise (0). Univariate regression analyses showed study size (PHet< 0.01) as the source of heterogeneity. TaqMan genotyping method emerged as significant source of heterogeneity but not PCR-RFLP (PHet = < 0.001 and 0.569, respectively, for Taqman and PCR-RFLP methods).

3.5 Sensitivity Analysis

A single study involved in the meta-analysis was removed each time to reflect the influence of the individual data set to the pooled ORs, and the corresponding pooled ORs were not significantly altered (Fixed effect OR range= 1.12-1.14; Random effect OR range= 1.13-1.15).

3.6 Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

Begger’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were performed to assess the publication bias. Review of funnel plot could not completely rule out the potential for publication bias at allelic level but Egger’s test result did not reveal publication bias (Y axle intercept = 0.31, (95%CI) = −0.39-1.01; t = 0.878, p = 0.382 for allelic model, Fig. 3). Also, Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test also indicated absence of publication bias (P2tailed=0.162) However, the fail-safe number was large enough to provide credence to our findings (Nfs0.05=417). Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method showed that, if the publication bias was the only source of the funnel plot asymmetry, it needed two more studies to be symmetrical. The value of Log OR did not change too much after the adjustment (Fig. 4). A cumulative meta-analysis was also done by sorting the studies in the sequence of largest to smallest, and analysis performed with the addition of each study. The point estimate of the study did not deviate with the addition of smaller studies, ruling out the possibility of publication bias.

Fig 3.

Funnel plot analysis to detect publication bias for the analyzed polymorphisms in GBC. Each dot represents an individual study for the indicated association. Log [OR], natural logarithm of odds ratio

Fig 4.

Funnel plot of Precision by Log odds ratio. The filled circles are missed studies due to publication bias. The bottom diamonds show summary effect estimates before (open) and after (filled) publication bias adjustment.

4. Discussion

Although there have been several descriptive reviews on this topic, to the best of authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review analyzing the effect of genetic determinants in GBC. In summary, we reviewed the available literature on genetic studies of GBC and conducted four independent meta-analyses for association between GBC and OGG1 rs1052133, TP53 rs1042522, GSTM1 and CYP1A1 rs1048943 polymorphisms. There was minimal evidence for a probable overall association between the studied polymorphisms and increased odds of GBC. However, due to small number of studies with an overall mediocre quality and lack of confirmatory studies, it is very difficult to draw any definitive conclusions.

There are two different classes of genes, mutations in which may give rise to cancer; high penetrance genes and low penetrance genes. Most of the cancer susceptibility alleles identified so far are rare and highly penetrant (for example, APC, BRCA1, BRCA2, MSH2, LMH1, PTEN, CDNK2A). Although these genes are directly involved in pathogenesis of various cancers, but their effect on all cancers is relatively small. The low penetrance genes show marked locus and allelic heterogeneity with multiple alleles of individual gene influencing cancer.

The pathophysiology of gallbladder carcinogenesis is still obscure and a combination of various factors including gallstones, infection, environmental carcinogens, diet and genetic variations might be involved (Table 5). Various evidences suggest that the causal pathway for GBC pathogenesis involves chronic inflammation of the biliary epithelium, which may be either due to mechanical irritation by gallstones or by bacterial infection [67-68]. A study from Utah Cancer Registry (UCR) estimated that 26% of all gallbladder cancers are familial [69].The Swedish Family-Cancer Database from the Swedish Cancer Registry also reported high risk for familial gallbladder cancer [70]. Genetic susceptibility to developing GBC requires an association between different polymorphic genes and a patient’s ability to respond to an environmental insult. Although a number of studies have reported positive associations between genetic polymorphisms and GBC, most of them are inconsistent and have not been replicated. Moreover, gallbladder cancer being multigenic and multifactorial, the prior probability of a particular genetic variation increasing the risk of gallbladder cancer is miniscule even with very significant p-values. Thus, in the present meta-analysis, we incorporated data from 1046 cases and 2310 controls retrieved from forty five studies to evaluate the association of various SNPs in GBC pathogenesis. Overall, the evidence in this review supports a modest involvement of inflammatory and DNA repair pathway genes in GBC susceptibility.

Table 5.

Factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis of gallbladder cancer

| Independent / Established/Major | Dependent / Emerging/Novel |

|---|---|

|

NON MODIFIABLE Age [87] Gender [87] Family history [69, 88] |

Tobacco [89-90] |

|

MODIFIABLE Gallstone disease [87, 91-94] Chronic cholecystitis [77, 95] Chronic infection [87, 96-97] Obesity [98] High parity [93, 99-101] Anomalous pancreatobiliary duct junction [102] Porcelain gallbladder [103] |

Chemical carcinogenesis [104-105] |

| Mustard oil [106] | |

| Early age at first pregnancy [93, 99-101] | |

| Oral contraceptive use [89, 99, 107] | |

| Red chili pepper [64, 108] | |

| Occupational exposure [77] | |

| Secondary bile acids [109] | |

| Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis [110- 111] | |

| Heavy metals [5, 112] | |

| Genetic factors | |

| Increased oxidative stress | |

| Ethnic and geographic variation [87] |

To identify heterogeneity among studies due to genotyping methods used, we did metaregression analysis which revealed significant difference between TaqMan genotyping and PCR-RFLP based genotyping, indicating potential misclassification It should be noted that although TaqMan is a better genotyping method than PCR-RFLP, it is not immune to errors [71]. Meta regression also showed study size to be a potential source of between-study heterogeneity.

One of the important issues in every meta-analysis is publication bias. Since meta-analysis summarizes quantitative evidence from multiple studies, the publication bias effect of the literature included in the analysis can bias the meta-analytic results, potentially generating overstated conclusions. In the present study, the funnel plot for overall results was symmetrical, suggestive of a small probability of publication bias. The Egger’s test and Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test also did not indicate statistically significant potential for publication bias. However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of publication bias as the significance of these tests and the typical funnel plot have been questioned [72]. We also performed sensitivity analyses by using HWE-adjusted ORs and corresponding variances. The results did not modify the risks of development of GBC.

One other factor that we examined was the timing of publication. We were interested to know whether the average scores observed in each year improved over time or not. We did observe an improvement in the quality score of published studies with respect to time.

Although we have only analyzed the effect of polymorphisms on GBC risk, the polymorphisms may interact with environmental exposures which might act as modifiers of gallbladder carcinogenesis. However, interactions between environmental factors and genetic factors have not yet been evaluated completely. A prospective study by Yagyu et al [73] evaluated the association of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption with the risk of GBC death. The study associated smoking with an elevated risk of death from GBC. Drinking posed an elevated risk only among males. Another study by Shukla et al [74] associated tobacco chewing with an increased risk of GBC. A study by Pandey et al [21] looked at a possible association between CYP1A1 rs4646903 polymorphism and tobacco status. In the case-only analysis, they found an elevated GBC risk with TC genotype (OR 4.1, 95% CI=1.3–11.9). Srivastava et al analyzed the interaction of CCR5 Δ32 and OGG1 and XRCC1 polymorphisms with tobacco usage in 2 separate studies [10, 75] but the authors did not find any associated significantly increased risk with GBC.

About 40%–100% cases of GBC have been found to be associated with gallstones [76-77]. Many studies have evaluated a potential interaction between polymorphisms and gallstones on GBC risk. Srivastava et al [75] looked for a relationship between polymorphisms of DNA repair pathway genes and modulation of GBC risk in presence of gallstones. The frequency distribution of OGG1 Cys/Cys genotype in GBC patients with gallstone was significantly higher and conferred high risk for GBC (OR=5.50). This result is consistent with an earlier study, in which Jiao et al [51] showed a near-significant increase in risk for gallbladder cancer for gallstone presence with the OGG1 Ser/Cys and Cys/Cys genotypes (OR=2.2 and OR=6.1, respectively). Patients with the Cys allele at codon 326 have a lower DNA-repair activity, and this decreased activity might be expected to increase GBC risk, especially among those who are exposed to high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by gallstones. On the other hand, significant negative association was also observed for XRCC1 Arg399Gln Gln/Gln genotype in GBC patients without gallstones compared with controls (OR = 0.27). Another study by the same authors observed difference in frequency of CCR5 Δ32 allele in GBC patients without gallstones when compared with healthy controls conferring high GBC risk (OR = 3.21) [10]. Hou et al [78] reported, for CYP17 rs743572 polymorphism, that relative to individuals with the A2/A2 genotype, those with the A1 allele and having a history of diabetes along with biliary stones had a 3-fold risk of gallbladder cancer.

Obesity and use of oral contraceptives are important risk factors for gallbladder cancer exerting their effect via increased estrogen levels [79]. Park et al [18] found a statistically significant interaction between BMI and the CYP1A1 rs2606345 SNP on GBC risk, with non-obese (BMI<23 kg/m2) carriers of the T allele having a 3.3-fold risk (95% CI=1.8–6.1). The possible reason for this association was not apparent since higher levels of bioavailable estradiol and adipokines which are linked to GBC have been observed in obese subjects [80]. The authors also found female carriers of the SHBG rs6259 variant genotype to be at 3.2-fold increased risk of gallbladder cancer (95% CI=1.1–9.1).

There are various limitations in our study the first being the vulnerability to several types of bias, primarily the publication bias. The proportion of published literature with positive result surpasses the one with negative results resulting in an inherent bias toward the publication with positive results. Another potential limitation is analysis reporting bias caused by researchers who report only a portion of their analyses. There was no access to the unpublished data of many association studies in GBC. Inclusion of data from all the available studies could have improved our power, but attempts for unpublished allele frequency data by directly contacting the authors unfortunately remained futile. All this suggests that in spite of following a systematic methodology, the included samples may not be the true representative of present genetic association studies of GBC. Since meta-analysis is a retrospective research, it cannot avoid the influence of methodological shortcomings.

Also, the present meta-analysis included only case–control studies in GBC which are prone to confounding and selection bias particularly due to the complex aetiology of the disease. Moreover, due to small numbers of studies for OGG1 rs1052133, TP53 rs1042522, GSTM1 and CYP1A1 rs1048943 polymorphisms, we were unable to construct funnel plots and perform Egger’s test distorting the results due to potential publication bias. We also could not perform the ethnic-specific meta-analysis to detect associations in ethnic groups due to limited data. Also, considering the close association of GBC and gallstone, it would have been interesting to examine the candidate gene polymorphisms with gallstone status which could have provided a clue for GBC susceptible individuals at an earlier stage. However, such analysis was not feasible due to limited availability of data on gallstone status.

Our results need to be interpreted with caution as they are based on unadjusted estimates. A more precise analysis stratified by age, sex, and gallstone status could not be performed due to limitation of data which also restricted our ability for detecting possibility sources of heterogeneity.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, although some genes show promise, the existing candidate gene studies in GBC susceptibility have so far been insufficient to confirm any association. The small number of studies decrease the potential generalization of results and also the statistical power [81-82]. Thus, only preliminary conclusions can be drawn at this stage. Owing to its complex aetiology, it is extremely implausible that any single SNP or risk factor contributes significantly to the development of GBC in a large fraction of patients. Therefore, future research should focus on other low penetrance gene polymorphisms with more comprehensive approaches utilizing complex hypotheses for identification of potential gene–gene, gene–environment interactions and high-risk haplotypes. DNA copy number variations (CNVs) are also an important component of genetic variation covering at least 10% of the human genome. It is assumed that CNVs along with SNPs can explain a large portion of the genetic basis of cancer. Whole exome sequencing (WES) and expression microarray might also help to identify new mutations that may contribute in a significant way to gallbladder cancer pathogenesis. Moreover, genome-wide association (GWA) studies using multistage design might be more fruitful to investigate the role of genetic components in complex diseases such as gallbladder cancer. Understanding the intricate mechanisms of genetic pathways involved in GBC etiopathogenesis would be helpful to better identify subjects at high risk.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 1.

The average score of published genetic association studies in GBC, expressed as a percentage of total possible scores from 0 to 1, with standard error of the mean. Studies were divided into year of publication. There was an evidence of a trend towards improvement over time (R2=0.69; logarithmic trendline).

Acknowledgement

This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (USA), Indian council of Medical Research (ICMR), DST and CSIR Government of India.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Pitt HA, Dooley WC, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Malignancies of the biliary tree. Curr Probl Surg. 1995;32:1–90. doi: 10.1016/s0011-3840(05)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nagorney DM, McPherson GA. Carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. Semin Oncol. 1988;15:106–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dhir V, Mohandas KM. Epidemiology of digestive tract cancers in India IV. Gall bladder and pancreas. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lazcano-Ponce EC, Miquel JF, Muñoz N, Herrero R, Ferrecio C, Wistuba II, Alonso de Ruiz P, Aristi Urista G, Nervi F. Epidemiology and molecular pathology of gallbladder cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:349–364. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.6.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pandey M. Environmental pollutants in gallbladder carcinogenesis. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:640–643. doi: 10.1002/jso.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pandey M, Shukla VK. Diet and gallbladder cancer: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:365–368. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kapoor VK, McMichael AJ. Gallbladder cancer: an ‘Indian’ disease. Natl Med J India. 2003;16:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Srivastava A, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. CYP7A1 (−204 A>C; rs3808607 and −469 T>C; rs3824260) promoter polymorphisms and risk of gallbladder cancer in North Indian population. Metabolism. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.021. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Srivastava A, Mittal B. Complement Receptor 1(A3650G RsaI and Intron 27 HindIII) Polymorphisms and Risk of Gallbladder Cancer in North Indian Population. Scand J Immunol. 2009;70:614–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Srivastava A, Pandey SN, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. CCR5 Delta32 polymorphism: associated with gallbladder cancer susceptibility. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67:516–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Srivastava A, Pandey SN, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Role of genetic variant A-204C of cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) in susceptibility to gallbladder cancer. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Srivastava A, Pandey SN, Dixit M, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Cholecystokinin receptor A gene polymorphism in gallstone disease and gallbladder cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:970–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Srivastava A, Pandey SN, Pandey P, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. No association of Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism in susceptibility to gallbladder cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2008;27:127–132. doi: 10.1089/dna.2007.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Srivastava A, Srivastava K, Pandey S, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms of DNA Repair Genes OGG1 and XRCC1: Association with Gallbladder Cancer in North Indian Population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1695–1703. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Srivastava A, Tulsyan S, Pandey SN, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the ABCG8 transporter gene is associated with gallbladder cancer susceptibility. Liver Int. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Polymorphisms in ERCC2, MSH2, and OGG1 DNA Repair Genes and Gallbladder Cancer Risk in a Population of Northern India. Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/cncr.25063. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Pandey S, Kumar A, Mittal B. Functional polymorphisms of the cyclooxygenase (PTGS2) gene and risk for gallbladder cancer in a North Indian population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:774–780. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Park SK, Andreotti G, Sakoda LC, Gao YT, Rashid A, Chen J, Chen BE, Rosenberg PS, Shen MC, Wang BS, Han TQ, Zhang BH, Yeager M, Chanock S, Hsing AW. Variants in hormone-related genes and the risk of biliary tract cancers and stones: a population-based study in China. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:606–614. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Wang BS, Shen MC, Zhang BH, Niwa S, Chen J, Fraumeni JF., Jr. Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1577–1582. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hsing AW, Sakoda LC, Rashid A, Andreotti G, Chen J, Wang BS, Shen MC, Chen BE, Rosenberg PS, Zhang M, Niwa S, Chu L, Welch R, Yeager M, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Gao YT, Chanock SJ. Variants in inflammation genes and the risk of biliary tract cancers and stones: a population-based study in China. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6442–6452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pandey SN, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Association of CYP1A1 Msp1 polymorphism with tobacco-related risk of gallbladder cancer in a north Indian population. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:77–81. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282b6fdd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pandey SN, Dixit M, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Lipoprotein receptor associated protein (LRPAP1) insertion/deletion polymorphism: association with gallbladder cancer susceptibility. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37:124–128. doi: 10.1007/s12029-007-9002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pandey SN, Jain M, Nigam P, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Genetic polymorphisms in GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, GSTM3 and the susceptibility to gallbladder cancer in North India. Biomarkers. 2006;11:250–261. doi: 10.1080/13547500600648697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pandey SN, Modi DR, Choudhuri G, Mittall B. Slow acetylator genotype of N-acetyl transferase2 (NAT2) is associated with increased susceptibility to gallbladder cancer: the cancer risk not modulated by gallstone disease. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:91–96. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.1.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pandey SN, Srivastava A, Dixit M, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Haplotype analysis of signal peptide (insertion/deletion) and XbaI polymorphisms of the APOB gene in gallbladder cancer. Liver Int. 2007;27:1008–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vishnoi M, Pandey SN, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. IL-1 gene polymorphisms and genetic susceptibility of gallbladder cancer in a north Indian population. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;186:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vishnoi M, Pandey SN, Choudhury G, Kumar A, Modi DR, Mittal B. Do TNFA −308 G/A and IL6 −174 G/C gene polymorphisms modulate risk of gallbladder cancer in the north Indian population? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vishnoi M, Pandey SN, Modi DR, Kumar A, Mittal B. Genetic susceptibility of epidermal growth factor +61A>G and transforming growth factor beta1 −509C>T gene polymorphisms with gallbladder cancer. Hum Immunol. 2008;69:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Abbate A, Scarpa S, Santini D, Palleiro J, Vasaturo F, Miller J, Morales C, Vetrovec GW, Baldi A. Myocardial expression of survivin, an apoptosis inhibitor, in aging and heart failure. An experimental study in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Int J Cardiol. 2006;111:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Isomura Y, Yamaji Y, Ohta M, Seto M, Asaoka Y, Tanaka Y, Sasaki T, Nakai Y, Sasahira N, Isayama H, Tada M, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M, Koike K. A genetic polymorphism of CYP2C19 is associated with susceptibility to biliary tract cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1045–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Hunter DJ, Thomas G, Hirschhorn JN, Abecasis G, Altshuler D, Bailey-Wilson JE, Brooks LD, Cardon LR, Daly M, Donnelly P, Fraumeni JF, Jr., Freimer NB, Gerhard DS, Gunter C, Guttmacher AE, Guyer MS, Harris EL, Hoh J, Hoover R, Kong CA, Merikangas KR, Morton CC, Palmer LJ, Phimister EG, Rice JP, Roberts J, Rotimi C, Tucker MA, Vogan KJ, Wacholder S, Wijsman EM, Winn DM, Collins FS. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ioannidis JP, Lau J. Pooling research results: benefits and limitations of meta-analysis. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1999;25:462–469. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cohn LD, Becker BJ. How Meta-Analysis Increases Statistical Power. Psychol Methods. 2003;8:243–253. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ. 1997;315:1533–1537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hunter JE, Schmidt FL. Methods of metaanalysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Anonymous Freely associating. Nat Genet. 1999;22:1–2. doi: 10.1038/8702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bogardus STJ, Concato J, Feinstein AR. Clinical epidemiological quality in molecular genetic research: the need for methodological standards. JAMA. 1999;281:1919–1926. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.20.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Romero R, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, Olson J. The design, execution, and interpretation of genetic association studies to decipher complex diseases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1299–1312. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.128319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cooper DN, Nussbaum RL, Krawczak M. Proposed guidelines for papers describing DNA polymorphism-disease associations. Hum Genet. 2002;110:207–208. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Clark M, Baudouin S. A systematic review of the quality of genetic association studies in human sepsis. Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32:1706–1712. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0327-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, El Ghormli L, Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:434–442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1955;19:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Thakkinstian A, McElduff P, D’Este C, Duffy D, Attia J. A method for meta-analysis of molecular association studies. Stat Med. 2005;24:1291–1306. doi: 10.1002/sim.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Trikalinos TA, Salanti G, Khoury MJ, Ioannidis JP. Impact of violations and deviations in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium on postulated gene-disease associations. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:300–309. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ioannidis JP, Boffetta P, Little J, O’Brien TR, Uitterlinden AG, Vineis P, Balding DJ, Chokkalingam A, Dolan SM, Flanders WD, Higgins JP, McCarthy MI, McDermott DH, Page GP, Rebbeck TR, Seminara D, Khoury MJ. Assessment of cumulative evidence on genetic associations: interim guidelines. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:120–132. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tsuchiya Y, Sato T, Kiyohara C, Yoshida K, Ogoshi K, Nakamura K, Yamamoto M. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 1A1 and risk of gallbladder cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2002;21:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Singh MK, Pandey UB, Ghoshal UC, Srivenu I, Kapoor VK, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Apolipoprotein B-100 XbaI gene polymorphism in gallbladder cancer. Hum Genet. 2004;114:280–283. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tsuchiya Y, Baez S, Calvo A, Pruyas M, Nakamura K, Kiyohara C, Oyama M, Ikegami K, Yamamoto M. Evidence that genetic variants of metabolic detoxication and cell cycle control are not related to gallbladder cancer risk in Chilean women. Int J Biol Markers. 2010;25:75–78. doi: 10.1177/172460081002500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Polymorphisms in ERCC2, MSH2, and OGG1 DNA repair genes and gallbladder cancer risk in a population of Northern India. Cancer. 2010;116:3160–3169. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Huang WY, Gao YT, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Deng J, Shen MC, Wang BS, Han TQ, Zhang BH, Chen BE, Rosenberg PS, Chanock SJ, Hsing AW. Selected base excision repair gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to biliary tract cancer and biliary stones: a population-based case-control study in China. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:100–105. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jiao X, Huang J, Wu S, Lv M, Hu Y, Jianfu, Su X, Luo C, Ce B. hOGG1 Ser326Cys polymorphism and susceptibility to gallbladder cancer in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:501–505. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kimura A, Tsuchiya Y, Lang I, Zoltan S, Nakadaira H, Ajioka Y, Kiyohara C, Oyama M, Nakamura K. Effect of genetic predisposition on the risk of gallbladder cancer in Hungary. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tsuchiya Y, Kiyohara C, Sato T, Nakamura K, Kimura A, Yamamoto M. Polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 1A1, glutathione S-transferase class mu, and tumour protein p53 genes and the risk of developing gallbladder cancer in Japanese. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:881–886. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Jiao X, Ren J, Chen H, Ma J, Rao S, Huang K, Wu S, Fu J, Su X, Luo C, Shi J, Broelsch CE. Ala499Val (C > T) and Lys939Gln (A > C) polymorphisms of the XPC gene: their correlation with the risk of primary gallbladder adenocarcinoma : a case-control study in China. Carcinogenesis. 2010 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Park SK, Andreotti G, Rashid A, Chen J, Rosenberg PS, Yu K, Olsen J, Gao YT, Deng J, Sakoda LC, Zhang M, Shen MC, Wang BS, Han TQ, Zhang BH, Yeager M, Chanock SJ, Hsing AW. Polymorphisms of estrogen receptors and risk of biliary tract cancers and gallstones: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:842–846. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Srivastava A, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. CYP7A1 (−204 A>C; rs3808607 and −469 T>C; rs3824260) promoter polymorphisms and risk of gallbladder cancer in North Indian population. Metabolism. 2010;59:767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Pramanik V, Sarkar BN, Kar M, Das G, Malay BK, Sufia KK, Lakkakula BV, Vadlamudi RR. A Novel Polymorphism in Codon 25 of the KRAS Gene Associated with Gallbladder Carcinoma Patients of the Eastern Part of India. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011 doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Kumar A, Mittal B. Significant association between toll-like receptor gene polymorphisms and gallbladder cancer. Liver Int. 2010;30:1067–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Caspase-8 polymorphisms and risk of gallbladder cancer in a northern Indian population. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:684–692. doi: 10.1002/mc.20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Common genetic variants in pre-microRNAs and risk of gallbladder cancer in North Indian population. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:495–499. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. DNMT3B −579 G>T promoter polymorphism and risk of gallbladder carcinoma in North Indian population. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41:248–253. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism and increased risk of gall bladder cancer in women. DNA Cell Biol. 2010;29:417–422. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Kumar A, Mittal B. Gallbladder cancer predisposition: a multigenic approach to DNA-repair, apoptotic and inflammatory pathway genes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Baez S, Tsuchiya Y, Calvo A, Pruyas M, Nakamura K, Kiyohara C, Oyama M, Yamamoto M. Genetic variants involved in gallstone formation and capsaicin metabolism, and the risk of gallbladder cancer in Chilean women. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:372–378. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Xu HL, Cheng JR, Andreotti G, Gao YT, Rashid A, Wang BS, Shen MC, Chu LW, Yu K, Hsing AW. Cholesterol metabolism gene polymorphisms and the risk of biliary tract cancers and stones: a population-based case-control study in Shanghai, China. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:58–62. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]