Abstract

Monogenic diabetes caused by mutations in the glucokinase gene (GCK-MODY) is usually characterized by a mild clinical phenotype. The clinical course of diabetes may be, however, highly variable. The authors present a child with diabetes manifesting with ketoacidosis during the neonatal period, born in a large family with ten members bearing a heterozygous p.Gly223Ser mutation in GCK. DNA sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification were used to confirm GCK mutation and exclude other de novo mutations in other known genes associated with monogenic diabetes. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was used to assess daily glycemic profiles. At the onset of diabetes the child had hyperglycemia 765 mg/dl with pH 7.09. Her glycated hemoglobin level was 8.6% (70.5 mmol/mol). The C-peptide level was below normal range (<0.5 pmol/ml) at onset, and the three- and 6-month follow-up examinations. Current evaluation at age 3 still showed unsatisfactory metabolic control with HbA1c level equal to 8.1% (65.0 mmol/mol). CGM data showed glucose concentrations profile similar to poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. The patient was confirmed to be heterozygous for the p.Gly223Ser mutation and did not show any point mutations or deletions within other monogenic diabetes genes. Other family members with p.Gly223Ser mutation had retained C-peptide levels and mild diabetes manageable with diet (five individuals), oral hypoglycemizing agents (five patients), or insulin (one patient). This mutation was absent within all healthy family members. Heterozygous mutations of the GCK gene may result in neonatal diabetes similar to type 1 diabetes, the cause of such phenotype variety is still unknown. The possibility of other additional, unknown mutations seems to be the most likely explanation for the unusual presentation of GCK-MODY.

Keywords: Glucokinase, Neonatal diabetes, Monogenic diabetes, MODY diabetes

Introduction

Glucokinase (GCK) plays a crucial role in regulation and integration of glucose metabolism in beta cells and hepatocytes. Enzymatic activity of GCK is directly associated with insulin secretion which results in glucokinase acting as the main glucosensor for the beta cells [1–3].

Heterozygous GCK mutations result in diabetes following a dominant mode of inheritance (GCK-MODY) which in some cases may be misdiagnosed as idiopathic type 1 diabetes [4]. The clinical picture usually encompasses moderately elevated fasting hyperglycemia with mildly increased glycated hemoglobin levels. Ketoacidosis in patients with GCK-MODY is rarely observed, as are chronic complications of diabetes [5, 6].

Clinical presentation of diabetes among patients with biallelic (homozygous or compound heterozygous) mutations of the GCK gene is dramatically different, e.g., diabetes that develop during the initial days of life is difficult to control and generally unresponsive to treatment other than with insulin. Such a defect is detected in 5–10% of patients with persistent neonatal diabetes (PND) [7, 8]. Symptoms of PND with biallelic GCK mutations manifest during the initial days of life, with pronounced hyperglycemia, ketoacidosis, and severe clinical condition [9, 10]. Insulin-based treatment is ubiquitous, but achievement of optimal metabolic control may be difficult possibly due to the mixed pancreato-hepatic origin of the disorder. This report presents a large GCK-MODY family with broad spectrum of clinical diabetic phenotype among affected family members.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000 and accepted by the Institutional Bioethics Committee. Participants expressed their informed consent for participation in the study.

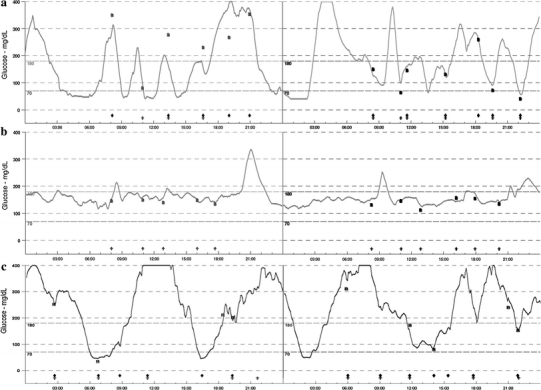

The authors sought to evaluate the clinical and genetic characteristics of a large family with GCK-MODY with one individual manifesting severe symptoms of diabetes during the neonatal period. For further evaluation, the patient, her sister, and two additional family members with diabetes were subjected to continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) examination, by means of Medtronic Diabetes CGMS (Medtronic, Northridge, CA, USA). Registered data from the CGMS Digital Recorder and the blood glucose meter were downloaded and analyzed with the appropriate dedicated software.

Genetic analysis

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood cells drawn into EDTA-coated vials. Isolation was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using QiaAmp DNA mini kits from Qiagen (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR amplification and DNA purification were carried out using standard methods [11, 12]. DNA sequencing was performed using BigDye Seq kit v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and pairs of specific oligonucleotide primers spanning the coding and promoter sequence of the GCK gene. Identification of mutations was performed by direct sequencing using the ABI 3130 genetic analyzer and DNA Sequencing Analysis Software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). For the comparative analysis of evaluated sequences, human genome reference using Sequencher software v4.1.4 (GeneCodes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used. DNA was also subjected to multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) testing according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a commercially available set MODY-P241 (MRC-Holland, Netherlands) to search for deletions in known monogenic diabetes genes including GCK. The same approach was implemented for mutation detection in coding and promoter regions (approximately 1,000 bp upstream from the first exon) of HNF1A, HNF4A, PDX1, HNF1B, NEUROD1, KCNJ11, ABCC8, and INS gene in the patient with onset of diabetes during the neonatal period. All genetic analysis was performed in the Immunopathology and Genetics Laboratory at the Department of Pediatrics, Oncology, Hematology, and Diabetology in Lodz, which is reference ISO9001 certified laboratory with European Molecular Genetics Quality Network (EMQN) collaboration.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as medians and 25–75% or as means with standard deviation depending on distribution. Normalization was performed against region-specific means and standard deviation with values presented as standard deviation scores (SDS). Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups were made using the Mann–Whitney’s U test. Statistical significance was declared when a P value 0.05 was observed. Statistica 8.0 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) statistical software was used to perform these analyses.

Subjects studied

Based on the above criteria, the authors found one child positive for a heterozygous GCK mutation who was diagnosed with PND (denoted as No5109 in the Nationwide Registry of Monogenic Diabetes). The patient, a female infant, presented with severe hyperglycemia (765 mg/dl), dehydration, glucosuria, and ketoacidosis (pH 7.09, BE 14 mM) on the day after her birth. The child was delivered by natural means from a second, uneventful pregnancy during the 36th week of gestation. Her birth weight equaled 1,760 g (<2 SDS), body length—46.3 cm (SDS −1.73), head circumference—30 cm (SDS −2.23), thorax circumference—26 cm (SDS −3.17), Apgar score equaled 7 on the first and 9 on the third minute of life.

For the first 72-h after diagnosis, she was treated with intravenous insulin (dose range: 0.1–0.3 units/kg/h) due to persistent hyperglycemia (mean value from that period equaled 340 mg/dl). On the 4th day of life, the girl was transferred from the Neonatal Care Unit to the Diabetes Unit. Subsequently, she was given insulin in multiple daily injections (mean daily dose equaled 0.9 U/kg). In the 7th week of life, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) therapy using a personal insulin pump was started. The insulin dose was reduced to 0.4 units/kg per day, and the blood glucose levels gradually normalized.

Follow-up visits after three and 6 months of treatment showed that fasting and glucagon stimulated C-peptide level was <0.5 ng/ml and HbA1c levels 6.5% (47.5 mmol/mol) and 8.3% (67.2 mmol/mol), respectively. No islet cell, anti-GAD65, anti-insulinoma-associated antigen-2, and anti-insulin autoantibodies were detected. At the age of 6 months, the girl weighted 6,400 g (SDS −1.37) and achieved all the psychomotor milestones adequate for that age.

Currently, at the age of 3 years, the child remains treated with CSII. Her daily insulin dose ranges between 0.6 and 0.8 units/kg per day, but metabolic control of diabetes is still not satisfactory (median HbA1c level equaled 8.1% (65.0 mmol/mol)), whereas psychomotor development was adequate for her age.

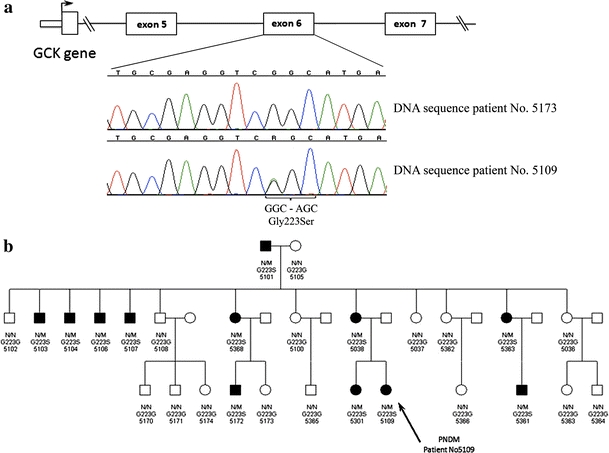

DNA sequencing revealed that the proband had heterozygous missense mutation C.667G > A in the GCK gene, which resulted in the amino acid substitution of glycine to serine at the 223rd position (p.Gly223Ser) (Fig. 1). Severe diabetes presentation, which is unusual among the carriers of heterozygous GCK mutation, suggested a possible biallelic genetic background (compound heterozygous or homozygous). Since only one heterozygous mutation in GCK locus was found, the authors decided to perform genetic screening for mutation in other known monogenic diabetes genes using both DNA sequencing (for point mutation detection) and MLPA techniques (for deletions/amplifications). These analyses did not reveal any other potentially causative lesions except the original one—the p.Gly223Ser in GCK.

Fig. 1.

a DNA sequencing results confirming the p.Gly223Ser mutation in a healthy family member (top chromatogram) and patient No5109 (bottom chromatogram); b full pedigree of the presented GCK-MODY family. Patient No5109—marked with an arrow—was diagnosed with neonatal diabetes. All patients marked as affected had diabetes or impaired fasting glucose and were heterozygous with the same p.Gly223Ser mutation located in the exon 6 of the GCK. N wild type, M p.Gly223Ser mutation

Mother of the presented patient (aged 21) was diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus that persisted after delivery. At the moment of evaluation, the state of her diabetes remained well controlled (HbA1c 5.8% (39.9 mmol/mol)) and she was able to maintain near-normoglycemic levels using diet only. Her fasting C-peptide level was well within the normal range (1.42 pmol/ml) and suggested retained beta cell function. Her siblings: one sister and one brother have been diagnosed initially with type 1 diabetes mellitus, which upon later verification turned out to be GCK-MODY. In depth evaluation of the presented family revealed that eleven out of 27 available family members had diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). This observation gave strong evidence toward a dominant mode of inheritance. Complete pedigree analysis of the described family and DNA sequencing results are depicted on Fig. 1 (a–b). Analysis of GCK gene showed that all subjects with diabetes (n = 9) or IGT (n = 2) were heterozygous carriers of the p.Gly223Ser substitution, and this mutation was absent in healthy family members. Interestingly, all affected family members but patient No5109, had mild clinical presentation of the disease, retained C-peptide levels, and in all cases but one did not require insulin treatment (Table 1). The CGM examination performed in patient No5109 showed 24-h glucose variability that was markedly different from typical GCK-MODY and similar to that observed among patients with type 1 diabetes (Fig. 2 a–c).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the presented family

| Characteristic | Patient No5109 | Other family members with diabetes or IGT | Healthy family members | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1 | 11 | 15 | – |

| % male | Female | 64% | 40% | – |

| Ketoacidosis at diagnosis |

pH 7.09 BE 14 mM |

None | NA | – |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 2nd day after birth | 17.5 (9.2–20.7) | NA | – |

| Fasting glucose at diagnosis (mg/dl) | 765 | 126 (115–132) | 90 (79–102) | <10−5 |

| HbA1c at diagnosis (%) (mmol/mol) |

8.6 70.5 |

6.2 (5.5–6.9) 44.3 (36.6–51.9) |

NA | – |

| Treatment | Insulin |

Insulin-1 Oral agents-5 Diet-5 |

NA | – |

| Median HbAc (%) |

8.1 (7.2–8.4) 65 (55.2–68.3) |

6.1 (5.5–6.4) 43.2 (36.6–46.5) |

5.4 (5.1–5.6) 35.5 (32.2–37.7) |

0.002 |

| Fasting C-peptide (pmol/ml) | <0.5 | 1.17 (0.7–1.5) | 1.01 (0.5–1.4) | 0.53 |

P values are given for comparisons between the healthy family members and the p.Gly223Ser mutation carriers. Data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges unless noted otherwise

NA not applicable, IGT impaired glucose tolerance

Fig. 2.

Continuous glucose monitoring results of patient No5109 with a phenotype of neonatal diabetes and heterozygous p.Gly223Ser mutation in glucokinase (a), her sister with mild phenotype and the same heterozygous p.Gly223Ser mutation (b) and a 3-year-old patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus (c)

Discussion

The majority of patients with heterozygous mutations of the glucokinase gene (GCK-MODY) may be diagnosed on clinical features. Symptoms of this form of diabetes are usually: fasting hyperglycemia >100 mg/dl, HbA1c levels elevated above normal limit but rarely exceeding 7.5% (58.5 mmol/mol), and small incremental rise of glycemia in oral glucose tolerance test [13]. The diagnosis is most often stated during the initial two decades of life [14]. The p.Gly223Ser mutation known to cause GCK-MODY in the proband’s family segregated with disease status in all individuals of the family, and thus a diagnosis of GCK-MODY was confirmed in 12 out of 27 individuals. The p.Gly223Ser mutation is a known defect of GCK leading to the development of typical MODY diabetes, which affects glucokinase activity in functional studies [15–17].

The observed low fasting C-peptide level—a trait generally attributed to homozygous GCK mutations [9, 10]—was the main feature confirming severe beta cell insufficiency in the presented individual. In her family, however, the level of C-peptide did not differ significantly upon the dependency of mutation carriage. This observation suggested the potential for an additional de novo mutation or a strong modulating effect of other genetic factors being active in the proband with neonatal diabetes.

GCK-MODY may be diagnosed in the neonatal period, but the clinical phenotype is most often mild with fasting plasma glucose within 6.0–7.6 mmol/l range [18, 19]. Thus, the authors were surprised to observe neonatal diabetes with such acute onset as mentioned earlier. Reports showed signs of ketoacidosis and significant hyperglycemia at onset to be extremely rare. Identification of a heterozygous mutation in GCK during the neonatal period is still a rare occurrence and, as was the case in the presented individual, may be a direct consequence of known GCK-MODY familial background, which guides the physician to proper diagnosis and rapid deployment of genetic diagnostics methods. A similar phenotype occurring in a non-familial setting would most likely result primarily in sequencing of KCNJ11, ABCC8, and INS genes as the most common causes of non-consanguineous cases of neonatal diabetes [20]. The relatively severe clinical course of diabetes with ketoacidosis and low birth weight suggested that the disease might have been actually caused by an additional de novo mutation in one of those genes exacerbating the effect of GCK mutations.

Coexistence of mutations in two separate genes causative of monogenic diabetes has been reported in several reports and different combinations. Cervin et al. [21] described the coexistence of HNF1A mutation with mitochondrial diabetes. Coexistence of KCNJ11 with GCK mutations has been described among Italian patients with monogenic diabetes [22]. Combinations of HNF1A and HNF4A mutations were also reported in patients with monogenic diabetes [23, 24]. A report by Odem et al. [25] suggested that coexistence of benign mutations in GCK and PDX1 could potentially lead to diabetes due to the joint effect of both defects, although this conclusion was not supported by any functional studies. Attempts to detect coexisting mutations in other MODY genes were therefore made, but no mutations were found in any of known MODY or PND genes. Similarly, no clinical features suggesting the presence of defects in genes associated with syndromic diabetes were found. Nevertheless, the possibility that patient No5109 had a de novo mutation in a yet undiscovered gene resulting in monogenic diabetes in addition to the p.Gly223Ser mutation of GCK remains the most likely explanation of the described phenotype discrepancy. This will necessitate reevaluation as new genes responsible for this disease are discovered and defined similarly to other patients with PND of unknown etiology.

The matter of increased “diabetes awareness” of the mother could contribute toward earlier diagnosis of diabetes in her second child if hyperglycemia was the only symptom at presentation, but cannot possibly explain the acute onset of symptoms. Finally, a plausible explanation for the observed phenotype is a modulating effect of common polymorphisms increasing the risk for developing diabetes. Potential candidates could include polymorphisms or mutations in genes participating in determining insulin secretion, insulin resistance, or beta cell apoptosis [26–30]. However, as the question which loci would be the most likely to exert such effect is unresolved, this hypothesis is purely speculative.

In conclusion, a heterozygous GCK mutation is a factor leading to monogenic diabetes with very discrepant phenotypes of the disease. Even within a single family the clinical presentation may range from severe diabetes manifesting in infancy to mild hyperglycemia detected accidentally during later stages of life. The possibility of additional, unknown genetic defects also seems to be the most likely explanation for the above-stated unusual presentation of GCK-MODY.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded from the Innovative Economy Operational Programme—Activity 1.2 (TEAM Program coordinated by the Foundation for Polish Science) and grants number: N402 478137 and N407 022535 of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

M. Borowiec and M. Mysliwiec are contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Fajans SS, Bell GI, Polonsky KS. Molecular mechanisms and clinical pathophysiology of maturity-onset diabetes of the young. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:971–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iynedjian PB, Mobius G, Seitz HJ, Wollheim CB, Renold AE. Tissue-specific expression of glucokinase: identification of the gene product in liver and pancreatic islets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1998–2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.7.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy MI, Froguel P. Genetic approaches to the molecular understanding of type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E217–E225. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00099.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polak M, Shield J. Neonatal and very-early-onset diabetes mellitus. Semin Neonatol. 2004;9:59–65. doi: 10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Froguel P, Zouali H, Vionnet N, et al. Familial hyperglycemia due to mutations in glucokinase. Definition of a subtype of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:697–702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303113281005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorini R, Klersy C, d’Annunzio G, et al. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young in children with incidental hyperglycemia: a multicenter Italian study of 172 families. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1864–1866. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huopio H, Otonkoski T, Vauhkonen I, et al. A new subtype of autosomal dominant diabetes attributable to a mutation in the gene for sulfonylurea receptor 1. Lancet. 2003;361:301–307. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skupien J, Malecki MT, Mlynarski W, et al. Assessment of insulin sensitivity in adults with permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus due to mutations in the KCNJ11 gene encoding Kir6.2. Rev Diabet Stud. 2006;3:17–20. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2006.3.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Njolstad PR, Sovik O, Cuesta-Munoz A, et al. Neonatal diabetes mellitus due to complete glucokinase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1588–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Njolstad PR, Sagen JV, Bjorkhaug L, et al. Permanent neonatal diabetes caused by glucokinase deficiency: inborn error of the glucose-insulin signaling pathway. Diabetes. 2003;52:2854–2860. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borowiec M, Fendler W, Antosik K, et al. Optimization of monogenic diabetes screening programme–initial report on recruitment efficacy of the TEAM project. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2010;16:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borowiec M, Antosik K, Fendler W et al (2011) Novel glucokinase mutations in patients with monogenic diabetes–clinical outline of GCK-MD and potential for founder effect in slavic population. Clin Genet. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01656.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hattersley AT. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young: clinical heterogeneity explained by genetic heterogeneity. Diabet Med. 1998;15:15–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199801)15:1<15::AID-DIA562>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields BM, Hicks S, Shepherd MH, et al. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY): how many cases are we missing? Diabetologia. 2010;53:2504–2508. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1799-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Herrero CM, Galan M, Vincent O, et al. Functional analysis of human glucokinase gene mutations causing MODY2: exploring the regulatory mechanisms of glucokinase activity. Diabetologia. 2007;50:325–333. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomson KL, Gloyn AL, Colclough K, et al. Identification of 21 novel glucokinase (GCK) mutations in UK and European Caucasians with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) Hum Mutat. 2003;22:417. doi: 10.1002/humu.9186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massa O, Meschi F, Cuesta-Munoz A, et al. High prevalence of glucokinase mutations in Italian children with MODY. Influence on glucose tolerance, first-phase insulin response, insulin sensitivity and BMI. Diabetes Study Group of the Italian Society of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (SIEDP) Diabetologia. 2001;44:898–905. doi: 10.1007/s001250100530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuesta-Munoz AL, Tuomi T, Cobo-Vuilleumier N, et al. Clinical heterogeneity in monogenic diabetes caused by mutations in the glucokinase gene (GCK-MODY) Diabetes Care. 2010;33:290–292. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prisco F, Iafusco D, Franzese A, Sulli N, Barbetti F. MODY 2 presenting as neonatal hyperglycaemia: a need to reshape the definition of “neonatal diabetes”? Diabetologia. 2000;43:1331–1332. doi: 10.1007/s001250051531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Patch AM, et al. Insulin mutation screening in 1, 044 patients with diabetes: mutations in the INS gene are a common cause of neonatal diabetes but a rare cause of diabetes diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2008;57:1034–1042. doi: 10.2337/db07-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cervin C, Liljestrom B, Tuomi T, et al. Cosegregation of MIDD and MODY in a pedigree: functional and clinical consequences. Diabetes. 2004;53:1894–1899. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massa O, Iafusco D, D’Amato E, et al. KCNJ11 activating mutations in Italian patients with permanent neonatal diabetes. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:22–27. doi: 10.1002/humu.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beijers HJ, Losekoot M, Odink RJ, Bravenboer B. Hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)1A and HNF4A substitution occurring simultaneously in a family with maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Diabet Med. 2009;26:1172–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forlani G, Zucchini S, Di RA, et al. Double heterozygous mutations involving both HNF1A/MODY3 and HNF4A/MODY1 genes: a case report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2336–2338. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odem J, Munzinger E, Violand S, et al. An infant with combination gene mutations for monogenic diabetes of youth (MODY) 2 and 4, presenting with diabetes mellitus requiring insulin (DMRI) at 8 months of age. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:550–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prudente S, Morini E, Trischitta V. The emerging role of TRIB3 as a gene affecting human insulin resistance and related clinical outcomes. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00592-008-0087-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szepietowska B, Moczulski D, Wawrusiewicz-Kurylonek N, et al. Transcription factor 7-like 2-gene polymorphism is related to fasting C peptide in latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:83–86. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen Y, Lu P, Dai L (2010) Association between resistin gene −420 C/G polymorphism and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Feng R, Li Y, Zhao D, et al. Lack of association between TNF 238 G/A polymorphism and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46:339–343. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edghill EL, Minton JA, Groves CJ, et al. Sequencing of candidate genes selected by beta cell experts in monogenic diabetes of unknown aetiology. JOP. 2010;11:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]