INTRODUCTION

Topical steroids are invaluable in controlling numerous inflammatory skin conditions. However, they can produce significant adverse effects if used inappropriately and without supervision as illustrated in the case below.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old male attended the ophthalmology department with a 2-week history of painless reduction in vision in his left eye. Past ophthalmic history included bilateral allergic conjunctivitis, primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) right eye, and ocular hypertension left eye, diagnosed on his first visit 18 months ago. Systemic enquiry revealed a history of asthma, hypertension, obesity, epilepsy, and atopic eczema. Current ophthalmic treatments included nedocromil sodium and latanoprost to both eyes. His only previous exposure to ophthalmic steroids was a 4-week course of dexamethasone 0.1% q.i.d. (standard practice) following uncomplicated left cataract surgery 8 months ago. Intraocular pressures (IOP) 6 weeks post-surgery were 23 and 18 mmHg right and left eye respectively.

Ocular findings were as follows: Snellen acuity 6/9; hand movement with IOP of 46 and 56 mmHg in the right eye and left eye respectively (upper limit of normal IOP is 21 mmHg). Both eyes were quiet with some evidence of corneal scarring and grade 4 open anterior chamber drainage angles. Fundus examination revealed bilateral optic disc cupping.

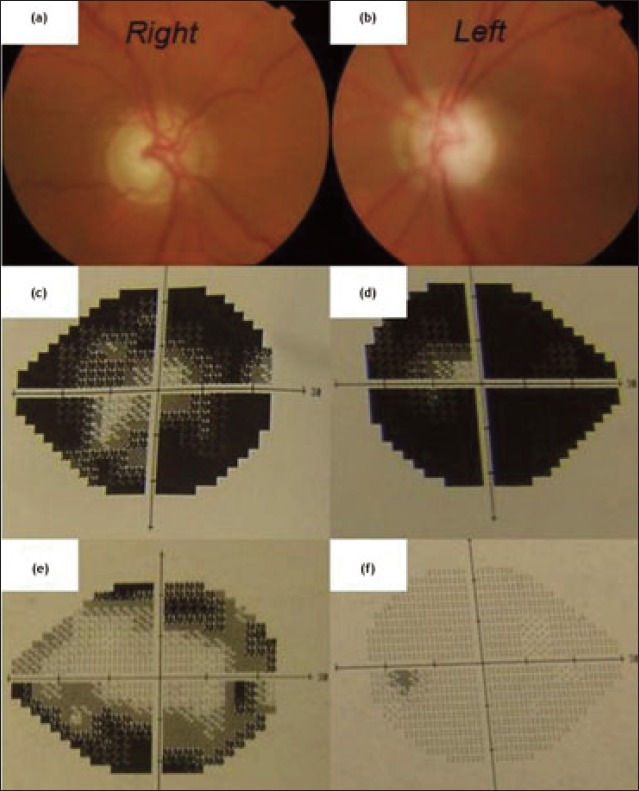

Treatment with systemic acetazolamide and topical ocular antihypertensives initially successfully normalised IOP in both eyes with slight improvement in visual acuity. On further questioning the patient revealed that as his eczema had flared up, and he had been applying 100 grams of Diprosone® (Schering-Plough) ointment each week continuously for the past 8 months to his sideburns, neck, and body, although he denied applying any near his eyes. A diagnosis of steroid-induced glaucoma was made. Subsequent follow-up examinations showed labile IOP levels (despite maximal topical antihypertensive treatment and withdrawal of cutaneous steroids) and marked deterioration in optic disc cupping and visual fields (Figure 1). He subsequently underwent trabeculectomy.

Figure 1.

Extensive optic disc cupping (a) & (b) with visual field loss after 8 months of excessive Diprosone® use (c) & (d); visual fields 6 months before diprosone use (e) & (f).

DISCUSSION

The link between a rise in IOP and corticosteroid use (by any route) is well established. However, the exact pathophysiology of steroid-induced glaucoma is unclear Suggested mechanisms include inhibition of degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the trabecular meshwork1 (TM); increased deposition of ECM in the TM; and cytoskeletal changes that inhibit the phagocytic clearance of debris.2 This leads to accumulation of glycoaminoglycans in the TM, thus increasing resistance to aqueous outflow. Furthermore, patients with POAG may exhibit increased peripheral vascular sensitivity to glucocorticoids resulting in enhanced local adverse effect in the eye.3

Adverse effects of facial steroids on the eye have been reported.4 Risk factors5 for developing IOP rise include: pre-existing history or family history of POAG, type 1 diabetes, connective tissue disorder such as rheumatoid arthritis, or high myopia. The elevation in IOP typically occurs within a few weeks of starting steroids and normalises a few weeks after cessation, although IOP may sometimes remain elevated, depending on potency and routes of steroid administration. Because of the insidious nature of the IOP rise, patients may remain asymptomatic until significant irreversible optic nerve glaucomatous damage has occurred. An estimated 75% of those receiving topical dexamethasone for 4weeks will develop a marked rise in IOP However, the likelihood of steroid-induced glaucoma or ocular hypertension in patients receiving non-ophthalmic steroids is unknown because it has not been studied systematically.6

The aim of this report is to reiterate awareness of the potentially blinding consequences of cutaneous corticosteroids that are largely preventable. Many topical steroid preparations are available over the counter in the UK and patients may erroneously perceive all topical treatments as innocuous. Therefore, it is vital that patients (and clinicians) are educated about side effects, the importance of adherence to treatment, and close monitoring for complications. The patient continuously used Diprosone for 8 months without adequate supervision with rapid marked visual deterioration as evidently illustrated on visual fields testing. The authors' recommendations are to use steroids cautiously, recognise individuals at risk of developing steroid-induced glaucoma, and ensure IOP is adequately monitored.

LEARNING POINTS

Topical steroids used via any route may cause a rise in IOP that usually normalises upon withdrawal of the offending agent.

Patient education on compliance with treatment and regular follow-up is essential, especially for those on potent topical steroids. The British National Formulary suggests that 15-30 grams of topical steroid for face and neck are usually suitable per fortnight for an adult on single daily application.

Chronic IOP rise may remain asymptomatic until extensive, irreversible damage to the optic nerves and visual fields has occurred. In particular, generalists should be discouraged from initiating topical ophthalmic steroid treatment without specialist input. IOP monitoring is important 2-4 weeks after initiation of ophthalmic steroids.

Patients with known glaucoma should avoid prolonged use of potent topical steroids on their face but if such treatment is clinically indicated, they may require closer IOP monitoring at the optician or ophthalmology unit. Individual cases should be discussed with the specialist in charge.

Consent

The patient has provided written consent for this article to be published.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Renfro L, Snow JS. Ocular effects of topical and systemic steroids. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10(3):505–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wordinger RJ, Clark AF. Effects of glucocorticoids on the trabecular meshwork: towards a better understanding of glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18(5):629–667. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stokes J, Walker BR, Campbell JC, et al. Altered peripheral sensitivity to glucocorticoids in primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol VISSCI. 2003;44(12):5163–5167. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross JJ, Jacob A, Batterbury M. Facial eczema and sight-threatening glaucoma. JR Soc Med. 2004;97(10):485–486. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.97.10.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kersey JP, Broadway DC. Corticosteroid-induced glaucoma: a review of literature. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(4):407–416. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spaeth GL, Monteiro de Barros DS, Fudemberg SJ. Visual loss caused by corticosteroid-induced glaucoma: how to avoid it. Retina. 2009;29(8):1057–1061. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181b32cfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]