Abstract

The aim of the study is to assess QoL depending on the choice of therapeutic regimen. From a total of 200 patients, half (n = 100) were treated with insulin (66% were females, age 52.1 ± 7.4—group A), the remaining 100 received oral treatment (74% females, age 63.3 ± 8.3—group B). For self-assessment of QoL, the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire was used. In group A, we found a negative influence of increased level of glycemia and occurrence of coexisting diseases in the somatic domain . In the psychological domain, frequent checkups showed a positive influence while circulatory failure produced negative results. For social domain, disobeying of recommended diet was strongly negative as well as increased levels of glycemia and coexisting disease for environmental domain. In group B, for somatic domain, correct values of glycemia and place of residence had positive influence. Incorrect values of BMI, WHR, and co-existing disease influenced the same domain negatively. In the psychological domain, a positive influence had place of residence but a negative BMI, ischemic heart disease, clinical complications. For environmental domain, a positive influence had correct values of glycemia but a negative BMI, ischemic heart disease and clinical complications. Finally, the social domain for group B was negatively influenced by BMI, ischemic heart disease, clinical complications, and lack of regular supervisions of glycemia level. A higher assessment of quality of life was found in the group of patients treated with oral hypoglycemic medicines in somatic and environmental domains, and in the group of patients treated with insulin in psychological domain.

Keywords: Diabetes, QoL, Treatment

Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic disease, leading to many complications and, as a result, to disability. Recently, a significant increase in the incidence of diabetes, especially type 2, can be observed. World Health Organization (WHO) anticipates that until 2025 the number of patients suffering from diabetes will increase from 380 million in 2007 to 418 million by 2025. This prevalence is influenced by the population aging, as well as changes in the way of living lead to in an increase in body mass and a decrease in physical activity [1].

Major clinical problems in diabetes include microangiopathies (nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy) and macroangiopathies (ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetic foot). Diabetic patients with microvascular complications show the strongest association between diabetes and cardiomyopathy—an association that parallels the duration and severity of hyperglycemia [2].

Co-existence of cardiovascular disease leads to a significant increase in clinical complications and thus to a substantial decrease in the patients’ quality of life (QoL). QoL of patients with diabetes is an important factor in analyzing the effectiveness of medical and other care. It results from a holistic need for approach to treatment and necessity of monitoring in the field of mental, physical, and social functioning (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

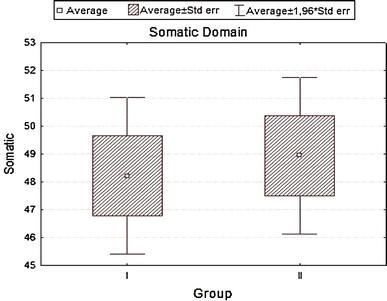

Somatic domain

Except for physical discomfort resulting from disease symptoms, patients also bear mental stress as well as family, professional, social, and financial costs. Therefore, in diabetic patients there is a bigger risk of psychopathologic disorders including depression [3, 4], anxiety [5, 6], and nutritional disorders [7]. There are several available publications concerning influence of the therapy on mortality, patient’s satisfaction, and his/her biomedical parameters, but only few publications concern influence of therapy on QoL (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

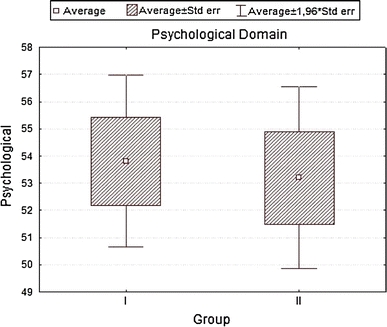

Psychological domain

Quality of life in relation to health status is a multidimensional notion covering physical, psychological, and social functioning which is affected by the disease and its treatment. It can be seen as a subjective sense of life satisfaction in basic fields of human functioning, i.e. physical condition, mental state, family, and beyond family relations, home, and life or professional activities, hobbies, sexual activity, material, and living conditions as well as spiritual/religious life [Text of the Constitution of The World Health Organization. Off. Rec. WHO 1948]. Any assessment of advantages and disadvantages of any therapy should include evaluation of its impact on patient’s QoL (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

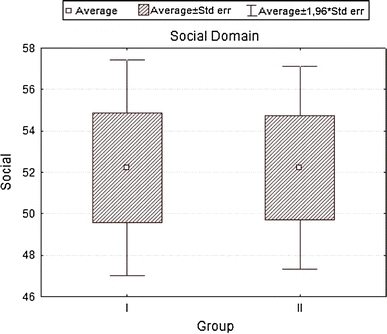

Social domain

The main goal of this study was to assess differences in QoL depending on the type of treatment chosen for diabetic type 2 patients (oral vs insulin). We also decided to analyze the influence of socio-demographic and clinical factors on quality of life measured by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) form in the same group of patients (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

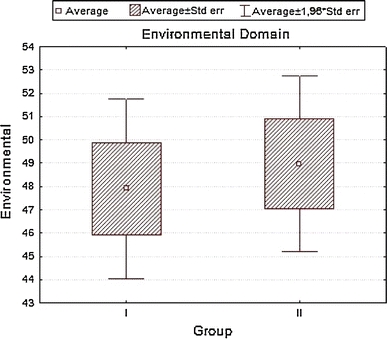

Environmental domain

Methods

Two hundred patients suffering from type 2 diabetes entered the study. Patients were assigned to two study groups. The first one consisted of insulin-treated patients (group A), while the second of patients treated with an oral hypoglycemic medication (group B). Group A patients had their diabetes recognized at least 5 years prior to inclusion and for at least two last years were on insulin. Also, group B patients had at least a 5-year history of diabetes, but they have never been insulin treated. All patients were included during their hospitalization due to diabetes exacerbation. Those who at the same time had an exacerbation of other (concomitant) chronic diseases or for any reasons were not able to participate and were excluded from the study. All patients gave their informed consent; none of those invited to participate refused.

The research was conducted at the Department of Internal Diseases and Allergology of the University Hospital in Wroclaw between October, 2008, and March, 2009. Every included patient was tested for the QoL in four domains: psychological, somatic, social, and environmental with use of general WHOQOL-BREF survey form. The WHO Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL) is a generic quality-of-life instrument that has been designed to be applicable to people living in different conditions or cultures. The WHOQOL is based on the patients subjective assessment of the perceived quality of life and in this way differs from many other instruments. WHOQOL also approaches the quality of life as a multidimensional concept. Further, it is being suggested that the WHOQOL-BREF provides a valid and reliable alternative to the assessment of domain profiles with WHOQOL-100 and is especially sensitive to the health-related quality-of-life status of those with chronic diseases. We have chosen the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire because it has been validated for the Polish population.

Further, the influence of independent variables on the QoL has been analyzed in multiple regression analysis. Predictors of quality of life considered in this study are the following: social and demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, education, place of residence); clinical factors (disease duration, physical activity, coexisting diseases, BMI & WHR); and laboratory values (glycemia and total cholesterol concentration in blood serum).

Physical activity was defined according to the British Regional Heart Study Questionnaire, on the basis of frequency and intensity of physical exercise, which assigned every patient to one of three groups: little active—less than three walks or bicycle rides a week; moderately active—walks or bicycle rides 3–4 times a week; highly active—walks or bicycle rides more than 4 times a week. The choice of the protocol resulted from the similarity of the patients’ profile.

STATISTICA 7.0 was used for statistical analysis. The distribution type for all variables was determined. The Shapiro–Wilk test was carried out. The critical level of significance was assumed at P < 0.05. For measurable (quantitative) variables, arithmetic means, standard deviations, medians, as well as the range of variability (extremes) were calculated, while for qualitative variables, the frequency (percentage) was determined. The analysis of qualitative variable was based on contingency tables and χ2 test. To compare quantitative variables in two non-related and related groups, the Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used, respectively. The Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted for means of variables, which did not meet criteria of variance analysis. Spearman rank correlation test was used out to check the relations between variables (QoL vs. clinical and laboratory factors). For each variable pair, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated, and the level P < 0.05 was assumed as statistically significant. Both answers to questions of the WHOQOL-BREF and overall results did not have normal distribution, which was confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. The impact of socio-demographic factors, clinical indexes, and risk factors on subjective evaluation of quality of life expressed by the WHOQOL-BREF score was determined based on the analysis of multiple regression.

Results

Group A consisted of 100 patients, including 66% of women and 34% of men aged 25–78 (mean ± SD; 52.1 ± 7.4 years). Group B—n = 100; 74% of women and 26% of men; aged 32–80 (63.3 ± 8.3 years). (Chi2 = 14.8186, P = 0.0006).

Patients in group A had a longer disease duration time. In group A, 50% of respondents suffered from diabetes for 1–5 years, 34%—5–10 years, and 16%—more than 10 years. In the group B, 20% of respondents were in the first year of disease duration, 76%—1 and 5 years; 4%—5–10 years (Chi2 = 20.1491, P = 0.0002).

Diabetic complications distribution differed among the two groups: retinopathies were diagnosed in 26% group A patients vs. 16% in group B; nephropathies 8% in group A and 5% in group B, neuropathies—4% in group A and 4% in group B; (Chi2 = 29.9745, P = 0.00001) The next analyzed factor was the presence of coexisting diseases. In group A, 84% of patients were also treated for arterial hypertension vs. 70% in group B, 24 vs. 8%—for circulatory failure, 10 vs. 14%—for ischemic heart disease, and 30 vs. 44%—for rheumatic disease (Chi2 = 3.268, ns).

Considering the available evidence, it seems that physical training (activity) can be an effective intervention helping to control glycemia, comparable with planed aerobic exercise [8]. For this reason, we looked at the physical activity of patients from both groups. In group A, 30% were found a little active patients (vs. 26% in B group); 54%—moderately active (vs. 66%); and 16%—highly active (vs. 8%). Calculated BMI value in group A was 28.63 ± 3.22 while in group B—26.73 ± 1.2, average WHR values were (0.83 ± 0.09) and (0.86 ± 0.13) (Chi2 = 7.8395, P = 0.0051), respectively.

Comparative analysis of quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF form) revealed some trends differentiating the both studied groups; however, they have not reached statistical significance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of domains with WHOQOL-BREF survey in both treated groups

| Group A | Group B | t | P | SD A | SD B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic | 48.21429 | 48.94841 | −0.362166 | 0.718544 | 7.83304 | 7.86834 |

| Psychological | 53.80556 | 53.19444 | 0.260331 | 0.795531 | 8.84813 | 9.32872 |

| Social | 52.22222 | 52.22222 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 14.50547 | 13.65512 |

| Environment | 47.90179 | 48.95833 | −0.382797 | 0.703270 | 10.82541 | 10.55228 |

Analyzing the impact of socio-demographic and clinical factors on QoL of patients in group A, we found a negative influence of increased level of glycemia (β = 0.43; SD = −5.35; P = 0.01) and occurrence of coexisting diseases—particularly circulatory failure (β = −0.39; SD = −6.63; P = 0.002) on QoL values in the somatic domain. In the psychological domain, frequent checkups in diabetic clinic showed a positive influence (β = 0.41; SD = 4.67; P = 0.01), while circulatory failure produced negative results (β = −0.38; SD = −8.22; P = 0.04). For social domain disobeying of recommended diabetic diet was strongly negative (β = −0.37; SD = −10.70; P = 0.003), while for environmental domain increased levels of glycemia (β = −0.39; SD = −6.93; P = 0.039) and coexisting circulatory failure (β = −0.40; SD = −9.85; P = 0.029) were again negative. In group B, for somatic domain, both correct values of glycemia (β = 0.36; SD = 7.05; P = 0.0005) and the place of residence (city) (β = 0.20; SD = 3.24; P = 0.036) had positive influence. Incorrect values of BMI (β = −0.49; SD = −3.27; P = 0.000004), WHR (β = −0.21; SD = −13.14; P = 0.04), coexisting ischemic heart disease (β = −0.33; SD = −7.73; P = 0.0006) influenced the same domain strongly negative. In the psychological domain, a positive influence had the place of residence (β = 0.24; SD = 4.61; P = 0.02), while a negative—incorrect values of BMI (β = −0.37; SD = −2.94; P = 0.0005), co-existing ischemic heart disease (β = −0.40; SD = −10.91; P = 0.0003), clinical complications of diabetes (β = −0.27; SD = −5.30; P = 0.008) and a long disease duration (β = −0.29; SD = −5.87; P = 0.007). For environmental domain, a positive influence had correct values of glycemia (β = 0.29; SD = 7.63; P = 0.0002), whereas a negative—incorrect values of BMI (β = −0.51; SD = −4.52; P = 0.00001), co-existing ischemic heart disease (β = −0.43; SD = −13.36; P = 0.000003), and clinical complications of diabetes (β = −0.38; SD = −8.24; P = 0.000009). Finally, the social domain for group B patients was negatively influenced by incorrect values of BMI (β = −0.41; SD = −4.68; P = 0.001), co-existing ischemic heart disease (β = −0.45; SD = −17.8; P = 0.0001), clinical complications of diabetes (β = −0.27; SD = −7.79; P = 0.01), and lack of regular supervisions of glycemia level (β = −0.24; SD = −3.52; P = 0.03), R 2 = 0.441.

Discussion

When designing our study to investigate QoL in diabetic patients, we had taken into account determinants’ division suggested by Rubin and Peyrot and had chosen two categories of determinants influencing QoL: socio-demographic (S-D) analysis and clinical variables. In our hands, S-D results do not show any significant influence on the QoL what is similar to the report of Wändell, who also proves that age, sex, and education level are poor predictors of QoL in diabetes [9]. There are data from other studies showing that some S-D parameters (age, education) correlate with QoL, however. For instance, Akinici demonstrated a higher QoL of married people with a lower educational level [10]. This may reflect the specificity of QoL-measurement-tool used, which again underlines the need to use only well-standardized and comparable questionnaires.

Age and sex distribution if subjects enrolled in our study were similar to those of the patients examined by Chaveepojnkamjorn [11]. Other demographic parameters, including city vs noncity resident status, were in concordance with group presented by Papadopoulos [12]. We failed, like several other investigators [13], to demonstrate an influence of disease duration on the quality of life of patients with diabetes. Most of our respondents have been diagnosed with diabetes less than 5 years prior to the study (group A:50%; group B: 76). This is consistent with Chaveepojnkamjorn study [11], while in Papadopoulos study the dominant group suffered from diabetes for over 10 years [12].

We have demonstrated a significant impact of both co-existing diseases (arterial hypertension, rheumatic disease, heart failure) and chronic complications of diabetes (sight deterioration, kidney failure, chronic myalgia, diabetic foot) on the QoL, similar to other investigators, such as Lloyd [14] and Jacobson [13], while Wändell [9] regards angiopathies and resulting conditions as poor predictors of the QoL [9].

While some studies looking into the relationship between the level of diabetes control and the QoL report low correlations, if any [15–18], in our research regular checkups as well as patients awareness of correct levels of glycemia correlated with the QoL, however. Also, overweight and obesity (BMI > 25 and >30, respectively) have been found both by us and other researchers [10] as important negative factors in determining the QoL.

Our QoL-WHOQOL-BREF-based-survey revealed a higher QoL assessment in the psychological domain for group A (insulin treatment), and a positive effects had regular control visits while negative had coexisting diseases (heart failure). Similar results were obtained by Nadeau et al., and regular control of glucose concentration, patient’s education, and regular visits to diabetologic clinic correlated positively with the QoL [19]. In group B, the low values in psychological domain were driven by high BMI values, WHR, and co-existing diseases (particularly ischemic heart disease), while positive trends were generated by the place of residence, reducing alcohol consumption, but negative had BMI values, disease duration, complications connected with diabetes and coexisting diseases (ischemic heart disease).

To the contrary, a higher assessment in the somatic and environmental domains for group B (oral treatment). Similarly, Redekop [20] and Brown [21] presented a lower QoL estimation by insulin-treated patients. In concordance with this, Stewart et al. demonstrated that patients not taking medication have higher QoL [22]. In patients intensely treated, this can result from the possible side effects of drugs as well as their influence on every day’s schedule (especially for insulin treated). This also confirms a study where type 2 diabetes patients reported worsening of QoL after treatment intensification (adding of oral agents or insulin) [23]. Social domain scored equally in both of our study groups.

Interestingly enough, we noted a higher assessment of QoL in all domains in women treated with insulin, while a significantly higher assessment of the QoL has been found in men treated with oral medicines. But this observation has to be further elucidated, and this research has to be continued to confirm. However, there are publications proving that there is a negative impact of the female sex on HRQoL, but the authors do not analyze the influence of treatment regimens or other disease-related factors [24].

Since patient’s QoL assessment is an important measure of a successful disease treatment, our study gives an important tool in terms of doctors’ attitude to diabetic patients depending on their sex, treatment regimen, co-existing diseases, or place of habitation. Especially, the QoL changes due to the treatment regimen seem to be important, since they can be taken as an additional advice for a physician choosing the regimen for the first time. Further research is needed, however, in order to precisely determine the role of some other demographic data, including education, disease duration, etc.

Conclusions

A higher assessment of quality of life was found in the group of patients treated with oral hypoglycemic medicines in somatic and environmental domains, and in the group of patients treated with insulin in psychological domain. On the assessment of the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes, in group A, a negative influence had co-morbidity especially heart failure, increased values of glycemia, and poor diabetes control, while a positive impact had a frequent diabetes checkups in a diabetic clinic. In group B, negative impact on the QoL had values of BMI & WHR as well as co-morbidity—particularly ischemic heart disease, occurrence of complications connected with diabetes and lack of regular control visits. Positive impact had good diabetes control.

Patients treated with insulin seem to be more stable as far as the quality of life is concerned; they are less susceptible to most disease-related factors (co-morbidity, overweight etc.) when compared to patients on oral hypoglycemic drugs. Irrespective of the treatment regimen, frequent checkups are an important positive factor for diabetic patients.

In our opinion, this study increases the chance to individualize doctors’ attitude to diabetic patients based on the treatment they are on. Further study is needed to prepare and assess such an individualized attitude in clinical practice.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Atkins RC, Zimmet P. Diabetic kidney disease: act now or pay later. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00592-010-0175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarquini R, Lazzeri C, Pala L, Rotella CM, Gensini GF (2010) The diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Diabetol. doi:10.1007/s00592-010-0180 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;16:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engum A, Mykletun A, Midthjell K, et al. Depression and diabetes: a large population-based study of sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical factors associated with depression in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabet Care. 2005;28:1904–1909. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovacs M, Goldston D, Obrosky DS, et al. Psychiatric disorders in youths with IDDM: rates and risk factors. Diabet Care. 1997;20:36–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyrot M, Rubin R. Levels and risks of depression and anxiety symptomatology among diabetic adults. Diabet Care. 1997;20:585–590. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly SD, Howe CJ, Hendle PJ, et al. Disordered eating behaviors in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Educator. 2005;31(4):572–583. doi: 10.1177/0145721705279049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanuso S, Jimenez A, Pugliese G, Corigliano G, Balducci S. Exercise for the management of type 2 diabetes: a review of the evidence. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wändell PE. Quality of life of patients with diabetes mellitus. An overview of research in primary health care in the Nordic countries. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23(2):68–74. doi: 10.1080/02813430510015296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinci F, Yildirim A, Gozu H, et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with type 2 diabetes in Turkey. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2008;79:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaveepojnkamjorn W, Pichainarong N, Schelp F et al (2008) Quality of life and compliance among type 2 diabetic patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 39(2):328–334 [PubMed]

- 12.Papadopoulos A, Kontodimopoulos N, Frydas A, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in type II diabetic patients in Greece. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson AM, de Groot M, Samson JA. The evaluation of two measures of quality of life in patients with type I and type II diabetes. Diabet Care. 1994;17(4):267–274. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.4.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd A, Sawyer W, Hopkinson P. Impact of long-term complications on quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes not using insulin. Value Health. 2001;4:392–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2001.45029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melidonis AM, Tournis SM, Kompoti MK, et al. Increased prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a rural Greek population. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6:534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nerenz DR, Repasky D, Whitehouse FW, et al. Ongoing assessment of health status in patients with diabetes mellitus. Med Care. 1992;5:MS112–MS124. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199205001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonnaville JJ, Snoek FJ, Colly LP, et al. Well-being and symptoms in relation to insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Care. 1998;6:919–924. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinberger M, Kirkman S, Samsa GP, et al. The relationship between glycemic control and health-related quality of life in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Med Care. 1994;12:1173–1181. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadeau J, Koski K, Strychar I, et al. Teaching subject with type 2 diabetes how to incorporate sugar choices into their daily meal plan promotes dietary compliance and does not deteriorate metabolic profile. Diabet Care. 2001;24:222–227. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redekop WK, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk RP, et al. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Dutch patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Care. 2002;25(3):458–463. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. Quality of life associated with diabetes mellitus in an adult population. J Diabet Popul. 2002;14:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(00)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart ST, Woodward RM, Rosen AB et al (2005) A proposed method for monitoring U.S. population health ratings. In: NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

- 23.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabet Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–218. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::AID-DMRR29>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eljedi A, Mikolajczyk RT, Kraemer RS, et al. Health-related quality of life in diabetic patients and controls without diabetes in refugee camps in the Gaza strip: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:268. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]