Abstract

The specific dermatoses of pregnancy represent a heterogeneous group of pruritic skin diseases that have been recently reclassified and include pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (syn. pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy), intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and atopic eruption of pregnancy. They are associated with severe pruritus that should never be neglected in pregnancy but always lead to an exact work-up of the patient. Clinical characteristics, in particular timing of onset, morphology and localization of skin lesions are crucial for diagnosis which, in case of pemphigoid gestationis and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, will be confirmed by specific immunofluorescence and laboratory findings. While polymorphic and atopic eruptions of pregnancy are distressing only to the mother because of pruritus, pemphigoid gestationis may be associated with prematurity and small-for-date babies and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy poses an increased risk for fetal distress, prematurity, and stillbirth. Corticosteroids and antihistamines control pemphigoid gestationis, polymorphic and atopic eruptions of pregnancy; intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, in contrast, should be treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. This review will focus on the new classification of pregnancy dermatoses, discuss them in detail, and present a practical algorithm to facilitate the management of the pregnant patient with skin lesions.

Keywords: Atopic eruption of pregnancy, Dermatoses of pregnancy, Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, Pemphigoid gestationis, Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, Pruritus

INTRODUCTION

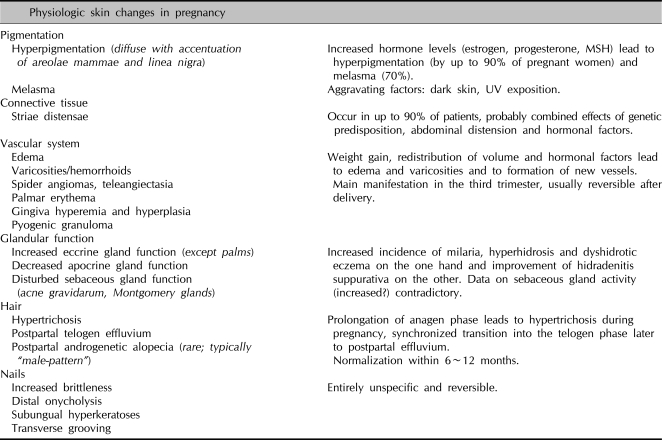

Complex endocrinologic, immunologic, metabolic and vascular changes associated with pregnancy may influence the skin in various ways. Skin findings in pregnancy can roughly be classified as physiologic skin changes, alterations in pre-existing skin diseases, and the specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Physiologic skin changes in pregnancy include changes in pigmentation, alterations of the connective tissue, vascular system, and endocrine function as well as changes in hair and nails (Table 1)1. Pregnancy is also known to influence the course of pre-existing skin diseases in both positive and negative ways2. A typical example is psoriasis, a classical Th1-associated disease, which often improves in pregnancy, only to worsen after delivery. A special case in this context is impetigo herpetiformis, which today is regarded as a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis presenting in pregnancy, accompanied by systemic signs such as fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea and tetanic seizures due to hypocalcemia. Diseases primarily associated with a Th2-immune response, such as lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune dermatoses, in contrast, characteristically deteriorate during pregnancy and improve after delivery. This is thought to be due to a temporary imbalance that develops between the differential cytokine secretion profiles and the preferential cellular or humoral dominated Th1 and Th2 mediated immune responses in order to prevent rejection of the fetus. Another disease typically affected in its course by pregnancy is acne, which most often improves, but can also be quite tenacious ("acne gravidarum"). Nevi tend to darken and enlarge, especially on the abdomen and breasts. The assumption that pregnancy has deleterious effects on the course of melanoma has not been substantiated; however, diagnostic and therapeutic decisions are often delayed in pregnancy leading to a more advanced tumor stage and hence worse prognosis.

Table 1.

Physiologic skin changes in pregnancy1

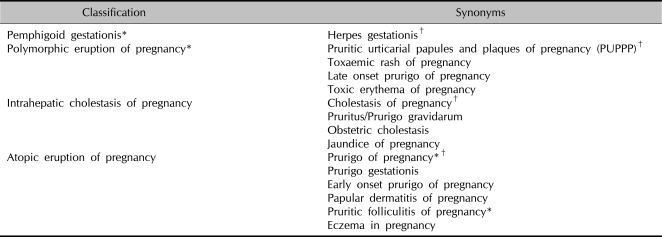

The specific dermatoses of pregnancy represent a heterogeneous group of severely pruritic inflammatory dermatoses associated exclusively with pregnancy and/or the immediate postpartum period. The rarity of these diseases, their variable clinical morphology, the lack of unequivocal diagnostic tests (with the exception of immunofluorescence in pemphigoid gestationis) as well as limited treatment options have led to confusing terminologies and have made their management difficult over decades. This article addresses the specific dermatoses of pregnancy in particular as a new classification has been recently established based on the results of a retrospective two-centre study on more than 500 pregnant patients3.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The first specific dermatosis of pregnancy reported was pemphigoid gestationis, which Milton described in 1872 under the name herpes gestationis4. The term "herpes" referred to the characteristic "creeping" blister formation. Only after the introduction of immunofluorescence microscopy and the discovery of specific linear complement deposition along the dermo-epidermal junction zone (DEJ) in 1973 could this disease entity be differentiated from the other dermatoses of pregnancy. In 1904 Besnier described another pregnancy-related disease which he termed prurigo gestationis5. The original description as well as illustration resemble today's picture of atopic dermatitis; of interest, at that time, what we define today as atopic dermatitis was known as prurigo. Costello (1941) employed this term and designated all pregnancy-related dermatoses which were not herpes gestationis as prurigo gestationis of Besnier and reported an incidence of 2%6. In the further course of time the disease was also referred to as early onset prurigo of pregnancy or prurigo of pregnancy7. Bourne (1962) described a further pregnancy-related dermatosis under the name toxemic rash of pregnancy, which appears on the abdomen often of small women with excessive weight gain and prominent striae, corresponding to today's polymorphic eruption of pregnancy8. Other synonyms followed such as late onset prurigo of pregnancy, toxic erythema of pregnancy and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP)7,9,10. Also in 1962, Spangler et al. described an entity whose existence is rightly questioned today. He differentiated a papular dermatitis from prurigo gestationis, which is clinically similar, on the grounds of biochemical alterations (raised levels of β-HCG in urine, lowered plasma cortisol levels) and reported a dramatically increased fetal death rate (early miscarriage and miscarriage in previous pregnancies were included!)11. In over 40 years, with the exception of one further case report by the same authors, no further case corresponding to the original description has surfaced. Even a recent large prospective study with extensive laboratory analyses could not detect a manifestation corresponding to "papular dermatitis"12. The first simplified classification of dermatoses of pregnancy was presented by Holmes et al. in 1982 and included pemphigoid gestationis, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and prurigo of pregnancy9. One year later they added a further dermatosis, pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy13,14. Whereas in the USA the terms herpes gestationis and PUPPP are still preferred, in Europe the names pemphigoid gestationis (points to the autoimmune pathogenesis and avoids association with herpes virus) and polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (points to the morphological spectrum) are widely accepted. The classification of Holmes and Black stood the test of time for two decades; in 1998 Shornick proposed a further adaptation15. He postulated that folliculitis of pregnancy was not an entity on its own but belonged to the spectrum of prurigo of pregnancy. He further introduced intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy into the classification of specific dermatoses of pregnancy. This disease had previously not appeared in the classification, as it displays only secondary skin changes. It seems sensible to include it in such as classification, as it is an important differential diagnostic consideration associated with potential fetal risk which can increase if the diagnosis is delayed or overlooked. Whereas pemphigoid gestationis, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy are accepted as independent entities, prurigo of pregnancy according to Holmes and Black as well as to Shornick is included only as a questionable independent entity. Even though it has been repeatedly suggested since the first description by Besnier that there might be a link to atopy, Holmes and Black were the first to postulate that it might merely be the result of pruritus in atopic pregnant women13. In a recent retrospective study on over 500 pregnant patients with pruritus, we were able to demonstrate conspicuous overlaps in clinical presentation and histopathology between female patients with atopic dermatitis, prurigo of pregnancy and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy (together 50% of our patient collective), thus leading us to group them together under the term atopic eruption of pregnancy3. This results in a new classification of specific dermatoses of pregnancy as follows: pemphigoid gestationis, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and atopic eruption of pregnancy (Table 2, 3).

Table 2.

Classification of the specific dermatoses of pregnancy3

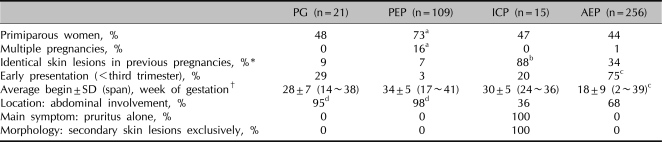

Table 3.

Significant differences in the clinical characteristics among the various pregnancy dermatoses in a retrospective two-center study (n=401)3

PG: pemphigoid gestationis, PEP: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, ICP: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, AEP: atopic eruption of pregnancy, SD: standard deviation.

PEMPHIGOID GESTATIONIS (SYNONYM: HERPES GESTATIONIS)

Pemphigoid gestationis is a rare, self-limited autoimmune bullous disorder that presents mainly in late pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period but can appear in any of the three trimesters. Beyond pregnancy it can also very rarely occur in association with trophoblastic tumors (choriocarcinoma, hydatidiform mole). Its incidence varies from 1:2.000 to 1:50.000~60.000 pregnancies depending on the prevalence of the HLA-haplotypes DR3 and DR416. There is also an increased risk to develop other autoimmune diseases, in particular Grave's disease. Pemphigoid gestationis tends to recur in subsequent pregnancies, with usually earlier onset and increasing severity. Only very rarely (5%) a pregnancy may be passed over ("skip pregnancies").

Pathogenetically, circulating complement fixing IgG antibodies of the subclass IgG1 (formerly known as "herpes gestationis factor") bind to a 180-kDa protein, BP-180 or bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 in the hemidesmosomes of the DEJ, leading to tissue damage and blister formation17. The immune response is even more highly restricted to the NC16A domain as it is in bullous pemphigoid. Of interest, the primary site of autoimmunity seems not to be the skin, but the placenta, as antibodies bind not only to the BMZ of the epidermis, but also to that of chorionic and amniotic epithelia, both equally of ectodermal origin. Aberrant expression of MHC class II molecules on the chorionic villi suggests an allogenic immune reaction to a placental matrix antigen, thought to be of paternal origin.

Clinical presentation

Pemphigoid gestationis presents with intense pruritus that occasionally may precede the manifestation of skin lesions. Initially, erythematous urticarial papules and plaques typically develop on the abdomen, characteristically involving the umbilical region, but may spread to the entire skin surface. In this so-called pre-bullous stage, differentiation between pemphigoid gestationis and polymorphic eruption of pregnancy is almost impossible, both clinically and histopathologically. Diagnosis becomes clear when lesions progress to tense blisters which resemble those in bullous pemphigoid. Facial and mucous membranes are usually spared16.

Diagnostic tests

Histopathological findings from lesional skin depend on the stage and severity of the disease. While the prebullous stage is characterized by edema of the upper and middle dermis accompanied by a predominantly perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and a variable number of eosinophils, the bullous stage reveals subepidermal blistering that, ultra structurally, may be located to the lamina lucida of the DEJ16.

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin, the gold standard in the diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis, shows linear C3 deposition along the DEJ in 100% of cases and additional IgG deposition in 30%. Depending on the technique applied, circulating IgG antibodies in the patient's serum may be detected by indirect immunofluorescence in 30~100% of cases, binding to the roof of the artificial cleft on salt-split skin. Antibody levels may also be monitored using modern ELISA and immunoblot techniques and show a good correlation with disease activity16,17.

Course and fetal prognosis

The natural course of pemphigoid gestationis is characterized by exacerbations and remissions during pregnancy, with frequent improvement in late pregnancy followed by a flare-up at the time of delivery (75% of patients). After delivery, the lesions usually resolve within weeks to months but may recur with menstruation and hormonal contraception. Rarely, severe courses with persistence of skin lesions over several years may occur. Fetal prognosis is generally good but there is an increase in prematurity and small-for-date babies. Only recently, it could be shown that this risk correlates with disease severity, as represented by early onset and blister formation, and not with corticosteroid treatment, as has been repeatedly speculated before18. Due to a passive transfer of antibodies from the mother to the fetus, about 10% of newborns may develop mild skin lesions which resolve spontaneously within days to weeks16.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the stage and severity of the disease and aims to control pruritus and to prevent blister formation. Only in cases of mild pre-blistering pemphigoid, topical corticosteroids with or without oral antihistamines may be sufficient16. All other cases require systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone, usually started at a dose of 0.5~1 mg/kg/day) which are considered safe in pregnancy19,20. When the disease improves, the dose can usually be reduced, but should be increased in time to prevent the common flare at delivery. Cases unresponsive to systemic corticosteroid treatment may benefit from immunoapheresis21. After delivery, if necessary, the full range of immunosuppressive treatment may be administered.

POLYMORPHIC ERUPTION OF PREGNANCY (SYNONYMS: PRURITIC URTICARIAL PAPULES AND PLAQUES OF PREGNANCY (PUPPP), TOXAEMIC RASH OF PREGNANCY, TOXIC ERYTHEMA OF PREGNANCY, LATE-ONSET PRURIGO OF PREGNANCY)

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy is a benign, self-limited pruritic inflammatory disorder that usually affects primigravidae in the last weeks of pregnancy or immediately postpartum (15%)22. Its incidence is about 1:160 pregnancies and the condition is associated with excessive maternal weight gain and multiple pregnancies22,23.

The pathogenesis of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy remains unclear. The main theories proposed by now focus on abdominal distension, hormonal and immunological factors24. The fact that polymorphic eruption of pregnancy starts within striae distensae at the time of greatest abdominal distension favors connective tissue damage due to overstretching to play a central role. The increase of CD1a cells in the inflammatory infiltrate could confirm the theory that previously inert structures develop antigenic character, thus triggering the inflammatory process. Hormonal and immunological changes have not definitively been shown to play a role; nor has an association with increased birth weight or male sex of the newborn been confirmed12,22.

Clinical presentation

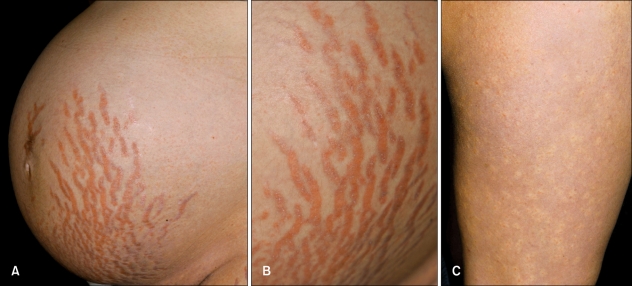

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy typically starts on the abdomen, within the striae distensae, with severely pruritic urticarial papules that coalesce into plaques, spreading to the buttocks and proximal thighs (Fig. 1). Often the eruption remains located to these sites but can quickly generalize in severe cases. In contrast to pemphigoid gestationis, the sparing of the umbilical region is a characteristic finding. Later-on, morphology becomes more polymorphic, and vesicles (1~2 mm in size; never bullae), widespread non-urticated erythema, targetoid and eczematous lesions develop in half of patients. The rash usually resolves within 4~6 weeks, independent of delivery22.

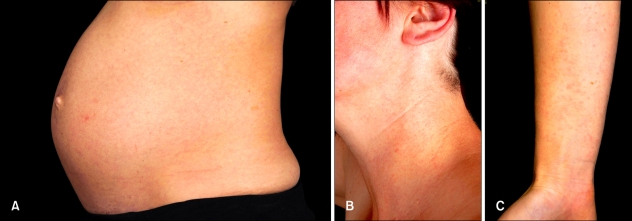

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the two most common dermatoses of pregnancy: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and atopic eruption of pregnancy. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy in a primigravida at 40 weeks gestation: Severely itchy, dark red, urticated striae distensae are present on the abdomen, typically sparing the umbilical region (A, B). Small urticated papules with a perilesional vasospastic halo also spread to the adjacent thighs (C).

Diagnostic tests

Histopathology is non-specific and varies with the stage of disease. Besides of a superficial to mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate intermingled with eosinophils, early biopsies show a prominent dermal edema, while later biopsies reveal frequent epidermal changes including spongiosis, hyper- and parakeratosis. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence investigations are essentially negative in polymorphic eruption of pregnancy.

Course and fetal prognosis

Maternal and fetal prognosis is unimpaired and there is no cutaneous involvement of the newborn23. Lesions are self-limited and the disease tends not to recur; the exception being multiple pregnancies, when both earlier presentation and manifestation in a subsequent pregnancy may occur.

Treatment

Symptomatic treatment with topical corticosteroids with or without antihistamines is usually sufficient to control pruritus and skin lesions. In severe generalized cases, a short course of systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone, 40~60 mg/day, for a few days in tapering doses) may be necessary and is usually very effective23.

INTRAHEPATIC CHOLESTASIS OF PREGNANCY (SYNONYMS: OBSTETRIC CHOLESTASIS, CHOLESTASIS OF PREGNANCY, JAUNDICE OF PREGNANCY, PRURITUS/PRURIGO GRAVIDARUM)

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is a reversible form of hormonally triggered cholestasis that typically develops in genetically predisposed individuals in late pregnancy. In contrast to the other dermatoses of pregnancy, it presents with pruritus and exclusively secondary skin lesions due to scratching. The incidence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy shows a striking geographical pattern; while its prevalence in Middle Europe is around 0.2~2.4%, it is particularly frequent in Scandinavia and South America, with highest rates in Chile (15~28%)25. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy runs in families and tends to recur in subsequent pregnancies (45~70%)25,26.

Pathogenetically, there is a defect in the excretion of bile salts resulting in elevated bile acids in the serum. This leads to severe pruritus in the mother, and, as toxic bile acids can pass into fetal circulation, may have deleterious effects on the fetus due to acute placental anoxia and cardiac depression. The reason for this defect seems to be multifactorial with genetic, hormonal, and exogenous factors being involved25. Endemic clustering and familial occurrence has pointed towards a genetic background; recently, mutations of certain genes encoding for transport proteins necessary for bile excretion (e.g., the ABCB4 [MDR 3] gene) have been identified in some intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy patients27. With normal hormone levels, this defect has no clinical implications; it only becomes evident with highest concentrations as in late pregnancy and/or with hormonal contraception. Furthermore, estrogen and progesterone metabolites have been seen to be cholestatic themselves28. Some authors also discuss additional environmental and dietary factors influencing the manifestation of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy such as decreased serum selenium levels, for instance29.

Clinical presentation

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy typically presents with sudden onset of severe pruritus that may start on palms and soles but quickly becomes generalized. It persists throughout pregnancy and may be tormenting. Of importance, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is not associated with primary skin lesions. Clinical features correlate with disease duration30. When pruritus starts, the skin usually is completely unaffected; later-on, secondary skin lesions develop due to scratching and range from subtle excoriations to severe prurigo nodules as pruritus persists. Skin lesions usually involve the extensor surfaces of the extremities, but may also affect other sites of the body such as buttocks and the abdomen. Jaundice, due to concomitant extrahepatic cholestasis, occurs in about 10% of patients, usually after 2~4 weeks, complicating the most severe and prolonged episodes31. These patients are at risk to develop steatorrhea with malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins including vitamin K and potential bleeding complications, as well as cholelithiasis25.

Diagnostic tests

Histopathology is non-specific; direct and indirect immunofluorescence are negative. The most sensitive indicator for the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is a rise of serum bile acid levels while routine liver function tests (including transaminases) may be normal in up to 30%25,30. In healthy pregnancies, total serum bile acid levels are slightly higher than in non-pregnant women and levels up to 11.0µmol/l (normal range, 0~6µmol/l) are accepted as normal in late gestation32,33. Hyperbilirubinemia is noted in only 10~20%; it should always lead to close surveillance of prothrombin time and an ultrasound examination of the liver may be necessary to exclude cholelithiasis in such cases.

Course and fetal prognosis

The prognosis for the mother is generally good. After delivery, pruritus disappears spontaneously within days to weeks but may recur with subsequent pregnancies and oral contraception25. In cases of jaundice and vitamin K deficiency, there is an increased risk for intra- and postpartum hemorrhage in both mother and child25. However, the key consideration in this disease is not maternal pruritus but the significantly impaired fetal prognosis. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for prematurity (19~60%), intrapartal fetal distress (22~33%) and stillbirths (1~2%) which correlates with higher bile acid levels, in particular if exceeding 40µmol/l25,34. Therefore, prompt diagnosis, specific therapy, and close obstetric monitoring as well as maternal counseling, in particular on the expected recurrence in subsequent pregnancies, are essential.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is the reduction of serum bile acid levels in order to prolong pregnancy and reduce both fetal risks and maternal symptoms. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the only treatment that has been shown not only to reduce maternal pruritus but to also improve fetal prognosis25,30,35-38. It is a naturally occurring, hydrophilic, non-toxic bile acid that has been successfully employed in Chinese medicine for over 5,000 years in treating various liver diseases and plays nowadays a key-role in treating hepatobiliary disorders. In intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, a dose of 15 mg/kg/day or, independent of body weight, 1 g/day is administered either as single dose or divided into 2~3 doses until delivery, when it usually can be stopped. With the exception of occasional mild diarrhea, there are no adverse effects. However, UDCA is not licensed for use in pregnancy, and thus requires special patient information ("off-label use"). Other drugs including antihistamines, S-adenosyl-L-methionine, dexamethasone, and cholestyramine could not improve fetal prognosis25. Of note, cholestyramine and other bile acid exchange resins may contribute to malabsorption of vitamin K with possible consecutive bleeding complications and should therefore be avoided39. In addition to UDCA treatment, close obstetric surveillance is indicated and includes weekly fetal cardiotocographic (CTG) registration at least from 34 weeks gestation on; early delivery as soon as lung maturity is achieved (36~37 weeks) is recommended by some authors40. An interdisciplinary management of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy by dermatologists, hepatologists, gynecologists, and pediatricians is absolutely mandatory.

ATOPIC ERUPTION OF PREGNANCY (SYNONYMS: PRURIGO OF PREGNANCY, PRURIGO GESTATIONIS, EARLY-ONSET PRURIGO OF PREGNANCY, PRURITIC FOLLICULITIS OF PREGNANCY, ECZEMA IN PREGNANCY)

Atopic eruption of pregnancy is a benign pruritic disorder of pregnancy which includes eczematous and/or papular lesions in patients with an atopic diathesis after exclusion of the other dermatoses of pregnancy. It is the most common dermatosis in pregnancy, accounting for 50% of patients, starts usually early, in 75% before the third trimester, and tends to recur in subsequent pregnancies due to the atopic background3.

The pathogenesis of AEP is thought to be triggered by pregnancy-specific immunological changes; a reduced cellular immunity and reduced production of Th1 cytokines (IL-2, interferon gamma, IL-12) stands in contrast to the dominant humoral immunity and increased secretion of Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10)41. Thus, the exacerbation of pre-existing atopic dermatitis as well as the first manifestation of atopic skin changes can be explained by a dominant Th2 immune response that is typical for pregnancy.

Clinical presentation

20% of patients suffer from an exacerbation of pre-existing atopic dermatitis with a typical clinical picture. The remaining 80% experience atopic skin changes for the first time ever or after a long remission (for example, since childhood). Of these, two-thirds present with widespread eczematous changes (so-called E-type AEP) often affecting typical atopic sites such as face, neck, décolleté, and the flexural surfaces of the extremities, while one-third have papular lesions (P-type AEP)3. The latter include small erythematous papules disseminated on trunk and limbs (Fig. 2), as well as typical prurigo nodules, mostly located on the shins and arms. A key-finding is the often severe dryness of the skin and frequent atopic "minor features" according to Hanifin and Rajka42.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the two most common dermatoses of pregnancy: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and atopic eruption of pregnancy. Atopic eruption of pregnancy in a primigravida at 22 weeks gestation: A discrete small papular rash involves the abdomen (A) as well as other common atopic sites such as the neck (B) and the flexural aspects of the upper extremities (C). Presence of severe xerosis and other atopic minor features as well as absence of striae distensae are clues to diagnosis.

Diagnostic tests

Histopathology is non-specific and varies with the clinical type and stage of the disease. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence are negative. Laboratory tests may reveal elevated serum IgE levels in 20~70%3.

Course and prognosis

Maternal prognosis is good even in severe cases as skin lesions usually respond quickly to therapy; recurrence in subsequent pregnancies is common. Fetal prognosis is unaffected, but there might be a risk of developing atopic skin changes in the infant, later-on.

Treatment

Basic treatment together with topical corticosteroids for several days will usually lead to quick improvement of skin lesions. Severe cases may require a short course of systemic corticosteroids and antihistamines; phototherapy (UVB) is a safe additional tool, particularly for severe cases in early pregnancy.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR TREATMENT DURING PREGNANCY

Topical treatment

Basic therapy using emollients adapted to the skin's state is essential and may contain urea (3~10%) and antipruritic additives such as menthol and polidocanol that are considered safe in pregnancy. Additional drying of the skin from washing, bathing or showering can be avoided by using mild, non-alkaline synthetic detergents capable of replacing lipids as well as showering or bath oils. During pregnancy, mild (face, intertriginous areas) or moderate (rest of body) topical corticosteroids may be applied, preferably the new, substituted products including methylprednisolone aceponate and mometasone furoate. Potent corticosteroids and uncontrolled long-term use should be avoided43.

Systemic treatment

When systemic corticosteroid treatment is necessary in pregnancy, also non-halogenated corticosteroids should be administered. In the placenta, cortisol, prednisone and prednisolone are inactivated enzymatically (mother:child=10:1), but not betamethasone and dexamethasone. Prednisolone is the corticosteroid of choice in pregnancy. The usual initial dose is 0.5~2 mg/kg/day depending on nature and severity of the disease. A maintenance dose should not exceed 10~15 mg/day in the first trimester, as a slightly increased risk for cleft lips/cleft palates can otherwise not be excluded. In treating dermatoses of pregnancy corticosteroids are usually used only as a short-time therapy (<4 weeks), so that side effects need not be expected. In rare cases with high-dose therapy over many weeks, fetal growth should be monitored by ultrasound. Should this therapy be continued up to delivery, possible adrenal insufficiency of the newborn must be kept in mind and treated accordingly. If systemic antihistamines are needed during pregnancy, older substances (dimethindene, clemastine, pheniramine) are preferable due to the greater experience with their use. This is especially valid for the first trimester. If a non-sedating antihistamine is required, loratadine and cetirizine can be administered in the second and third trimester19,20.

Algorithmic approach to the pregnant patient with pruritus

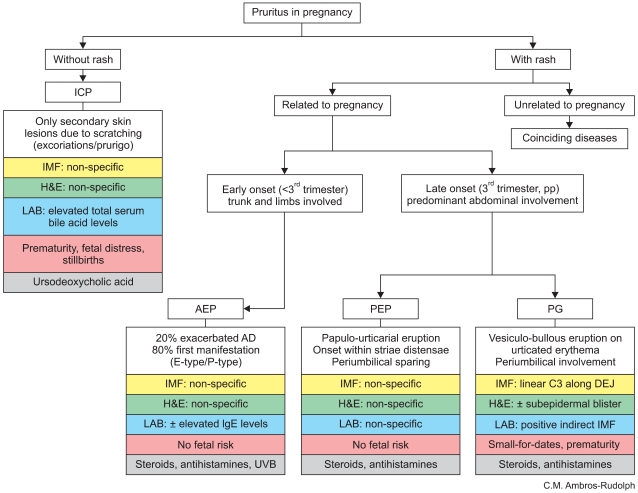

Pruritus in pregnancy should never be neglected and always lead to an exact work-up of the patient. Pruritus is the leading symptom of the specific dermatoses of pregnancy, but may also be associated with dermatoses that coincide by chance with pregnancy (e.g., pityriasis rosea, cutaneous infections, urticaria) and, in a first step, must be ruled out. In a second step, the four specific dermatoses of pregnancy need to be discriminated. A retrospective analysis of a large patient collective revealed the following significant differences helpful in differential diagnosis (Table 3)3. Primigravidae and multiple gestation pregnancies were particularly frequent in patients with polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and a history of previous pregnancies affected with similar skin changes was typically given in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. While pemphigoid gestationis, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy characteristically presented in late pregnancy, atopic eruption or pregnancy started significantly earlier, and onset before the third trimester occurred in 75% of patients. Abdominal involvement of skin lesions was stereotypical for pemphigoid gestationis and polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, whereas predominant affection of the extremities was observed in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, compared to equal involvement of trunk and limbs in patients with atopic eruption of pregnancy. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy was the only disease in that pruritus was the sole presenting symptom, followed by exclusively secondary skin lesions in all patients. Based on these findings, an algorithm (Fig. 3) was developed that may facilitate discrimination of the various pruritic dermatoses in pregnancy and points to appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures.

Fig. 3.

Algorithm for the management of pruritus in pregnancy3. ICP: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, AEP: atopic eruption of pregnancy, PEP: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, PG: pemphigoid gestationis, AD: atopic dermatitis, IMF: immunofluorescence, H&E: histopathology, LAB: laboratory findings, DEJ: dermo-epidermal junction.

References

- 1.Shornick JK. Pregnancy dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, Horn TD, Mancini AJ, Mascaro JM, editors. Dermatology. London, Edinburgh, New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Sydney, Toronto: Mosby; 2003. pp. 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambros-Rudolph CM. Disorders of pregnancy. In: Burgdorf WHC, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Landthaler M, editors. Braun-Falco's dermatology. 3rd ed. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag; 2009. pp. 1160–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambros-Rudolph CM, Müllegger RR, Vaughan-Jones SA, Kerl H, Black MM. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milton JL. The pathology and treatment of diseases of the skin. London: Robert Hardwicke; 1872. p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besnier E. Prurigo of pregnancy. In: Besnier E, Brocq L, Jacquet L, editors. La pratique dermatologique. Paris, France: Masson et Cie; 1904. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costello MJ. Eruptions of pregnancy. NY State J Med. 1941;41:849–855. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurse DS. Prurigo of pregnancy. Australas J Dermatol. 1968;9:258–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1968.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourne G. Toxaemic rash of pregnancy. Proc R Soc Med. 1962;55:462–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes RC, Black MM, Dann J, James DC, Bhogal B. A comparative study of toxic erythema of pregnancy and herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawley TJ, Hertz KC, Wade TR, Ackerman AB, Katz SI. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. JAMA. 1979;241:1696–1699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spangler AS, Reddy W, Bardawil WA, Roby CC, Emerson K. Papular dermatitis of pregnancy. A new clinical entity? JAMA. 1962;181:577–581. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050330007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughan Jones SA, Hern S, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Black MM. A prospective study of 200 women with dermatoses of pregnancy correlating clinical findings with hormonal and immunopathological profiles. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:71–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes RC, Black MM. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoberman E, Farmer ER. Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172–181. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins RE, Black MM. Pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis. In: Black MM, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, editors. Obstetric and gynecologic dermatology. 3rd ed. London: Elsevier Limited; 2008. pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zilikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: recent advances. JEADV. 2003;17(Suppl. 3):7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chi CC, Wang SH, Charles-Holmes R, Ambros-Rudolph C, Powell J, Jenkins R, et al. Pemphigoid gestationis: early onset and blister formation are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1222–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaefer C, Spielmann H, Vetter K. Arzneiverordnung in Schwangerschaft und Stillzeit, 7. Auflage. München: Urban & Fischer Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wöhrl S, Geusau A, Karlhofer F, Derfler K, Stingl G, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: treatment with immunoapheresis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2003;1:126–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1610-0387.2003.t01-1-03509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, Müllegger RR, Kerl H, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambros-Rudolph CM, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. In: Black MM, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, editors. Obstetric and gynecologic dermatology. 3rd ed. London: Elsevier Limit; 2008. pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmadi S, Powell F. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: current status. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lammert F, Marschall HU, Glantz A, Matern S. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2000;33:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reyes H. The spectrum of liver and gastrointestinal disease seen in cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992;21:905–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ropponen A, Sund R, Riikonen S, Ylikorkala O, Aittomäki K. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy as an indicator of liver and biliary diseases: a population-based study. Hepatology. 2006;43:723–728. doi: 10.1002/hep.21111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reyes H, Sjövall J. Bile acids and progesterone metabolites in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Ann Med. 2000;32:94–106. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes H, Báez ME, González MC, Hernández I, Palma J, Ribalta J, et al. Selenium, zinc and copper plasma levels in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, in normal pregnancies and in healthy individuals, in Chile. J Hepatol. 2000;32:542–549. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambros-Rudolph CM, Glatz M, Trauner M, Kerl H, Müllegger RR. The importance of serum bile acid level analysis and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a case series from central Europe. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:757–762. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rioseco AJ, Ivankovic MB, Manzur A, Hamed F, Kato SR, Parer JT, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a retrospective case-control study of perinatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:890–895. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brites D, Rodrigues CM, Oliveira N, Cardoso M, Graça LM. Correction of maternal serum bile acid profile during ursodeoxycholic acid therapy in cholestasis of pregnancy. J Hepatol. 1998;28:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carter J. Serum bile acids in normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:540–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2004;40:467–474. doi: 10.1002/hep.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zapata R, Sandoval L, Palma J, Hernández I, Ribalta J, Reyes H, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. A 12-year experience. Liver Int. 2005;25:548–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson C, Hems LM, Goulis DG, Walker I, Chambers J, Donaldson O, et al. Clinical outcome in a series of cases of obstetric cholestasis identified via a patient support group. BJOG. 2004;111:676–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palma J, Reyes H, Ribalta J, Hernández I, Sandoval L, Almuna R, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of cholestasis of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind study controlled with placebo. J Hepatol. 1997;27:1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kondrackiene J, Beuers U, Kupcinskas L. Efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid versus cholestyramine in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:894–901. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadler LC, Lane M, North R. Severe fetal intracranial haemorrhage during treatment with cholestyramine for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:169–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roncaglia N, Arreghini A, Locatelli A, Bellini P, Andreotti C, Ghidini A. Obstetric cholestasis: outcome with active management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;100:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.García-González E, Ahued-Ahued R, Arroyo E, Montes-De-Oca D, Granados J. Immunology of the cutaneous disorders of pregnancy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:721–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1980;92:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chi CC, Wang SH, Kirtschig G, Wojnarowska F. Systematic review of the safety of topical corticosteroids in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]