Abstract

Objectives

The Institute of Medicine has called for more coordinated cancer care models that correspond to initiatives led by cancer providers and professional organizations. These initiatives parallel those underway to integrate the management of patients with chronic conditions.

Methods

We developed five breast cancer patient and practice management process measures based on the Chronic Care Model. We then performed a survey to evaluate patterns and correlates of these measures among attending surgeons of a population-based sample of patients diagnosed with breast cancer between June 2005 and February 2007 in Los Angeles and Detroit (N=312, response rate 75.9%).

Results

Surgeon practice specialization varied markedly with about half of the surgeons devoting 15% or less of their total practice to breast cancer, while 16.2% of surgeons devoted 50% or more. There was also large variation in the extent of the use of patient and practice management processes with most surgeons reporting low use. Patient and practice management process measures were positively associated with greater levels of surgeon specialization and the presence of a teaching program. Cancer program status was weakly associated with patient and practice management processes.

Conclusion

Low uptake of patient and practice management processes among surgeons who treat breast cancer patients may indicate that surgeons are not convinced that these processes matter, or that there are logistical and cost barriers to implementation. More research is needed to understand how large variations in patient and practice management processes might affect the quality of care for patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: surgeons, breast cancer, care coordination

Introduction

The increasing complexity of cancer treatment decision-making and delivery is a challenge to patients and their physicians. Physicians must consider and select from a growing array of multimodal approaches to treatment and management. Patients face the daunting task of making many treatment decisions over a short period of time with input from different specialists generally consulted for the first time. This context has motivated interest in improving the organization of cancer care delivery from a variety of stakeholders.1-5 A review by the Institute of Medicine highlighted several potential physician and practice attributes that may be associated with better cancer treatment outcomes, including: physicians experience caring for patients with specific cancer conditions, the specialization of their clinical practice, institutional cancer case volume, or the presence of a teaching program.6 Some studies have demonstrated an association between physician specialization or institutional experience and better outcomes for patients with cancer.6-8

A growing literature describes recent efforts directed by providers to improve the delivery of cancer care. 3, 5, 9-13, 14, 15 Advances in research about chronic disease management provide an opportunity to inform these efforts. The chronic disease research agenda promotes change in provider groups to support evidence-based clinical and quality improvement in patient management across health care settings.16 The Chronic Care Model anchors this research and summarizes basic elements for improving care in health systems including multidisciplinary care teams, patient decision and care support, clinical information system and decision support, and performance measurement and feedback.17, 18 The model has been applied to research addressing the quality of care of patients with diabetes, heart disease, pulmonary disease and depression. Despite the many aspects of cancer that are shared with chronic diseases, there have been no large studies that have incorporated this potentially useful framework to evaluate quality of cancer care.

The treatment of breast cancer embodies many of the challenges patients and physicians face in the complex context of cancer care. Surgeons, in particular, have a primary role in clinical decision-making and treatment. All patients consult with and are treated by a surgeon at initial diagnosis and during initial phase of treatment.8, 19, 20 Some studies have shown that there is large variation in surgeon specialization in the treatment of breast cancer,6, 19, 21, 22 yet none have addressed variation in patient and practice management processes that may be associated with better outcomes. Given their primary role in treatment decision-making and delivery, surgeons can provide key insight about how care is organized for patients with breast cancer.

In this study, we developed a set of patient and practice management process measures for patients with breast cancer based on the Chronic Care Model, and a more specific framework for the development of cancer care quality measures23. Three measures related to patient management (multidisciplinary clinician communication, availability of clinical information, and patient decision support), and two measures related to practice management (access to information technology and practice feedback initiatives). We then evaluated patterns and correlates of these measures in a sample of attending surgeons who treated a large population-based sample of patients diagnosed with breast cancer between July 2005 through February 2007 in the metropolitan areas of Detroit and Los Angeles. We addressed two questions: (1) What is the distribution of patient and practice management process measures across surgeons? (2) What surgeon practice characteristics are associated with these measures? We hypothesized that surgeon with more experience and those practicing in more specialized settings would report higher scores on the patient and practice management process measures after controlling for other factors.

Methods

Details of the patient study have been published elsewhere. 24-27 In brief, we enrolled a population-based sample of 3133 women in the metropolitan areas of Los Angeles and Detroit, aged 20-79 years recently diagnosed with breast cancer during a period from June 2005 through February 2007. We excluded patients with Stage 4 breast cancer, those who died prior to the survey, those who could not complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish, and Asian women in Los Angeles (because of enrollment in other studies). Latinas (in Los Angeles) and African-Americans (in both Los Angeles and Detroit) were over-sampled. Eligible patients were accrued from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program registries of both regions. The Dillman survey method was employed to encourage survey response.28 Patients completed a survey approximately 9 months after diagnosis (96.5% by mail and 3.5% by phone), and this information was merged to SEER clinical data. The response rate was 72.1% (n=2268). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan, University of Southern California and Wayne State University.

An attending surgeon was identified for 98.9% of the patient sample using information from patient reports, pathology reports, and SEER. Surgeons were mailed a packet containing a letter of introduction, a survey, and a $40 subject fee approximately 14 months after the start of patient survey. We used a modified version of the Dillman method to optimize response.28 We identified 419 surgeons, of whom 318 returned completed questionnaires (response rate 75.9%).

Surgeon survey

The surgeon survey measures were developed based on the literature, our prior research, and the Chronic Care Model. First, we developed items for the five scales tailored to the breast cancer treatment context addressing the domains of patient and practice management; second, we pretested the items and response scales in a convenience sample of 10 surgeons; and third, we estimated scale reliability. The penultimate scales were piloted in a convenience sample of 34 surgeons at a national conference. The scales based on the final item sets were created by averaging the sum score of the responses across the scale items. A Cronbach's alpha was calculated and was above .9 for all scales. Confirmatory factor analysis with all of the patient management domain items confirmed the predominant loading of the items on their hypothesized sub-domains.

Table 1 describes the items in each scale. For each item in the three patient management sub-domains (multidisciplinary clinician communication, availability of clinical information, and patient decision support), surgeons were asked for what share of the patients they treated in the prior 12 months did the particular activity occur. We used a five-point Likert response category indicating the share of patients who received the particular practice process item (from none or very few to almost all). Two sub domains were developed that measured availability of aspects of practice management: access to information technology and practice feedback initiatives. The response category for each sub domain item was yes/no and questions were directed at the prior year of practice. Scales were calculated by adding the number of affirmative responses (from 0 to 3 items each).

Table 1. Distribution of surgeon responses to each item related to the patient management process measures (N=318).

| Share of patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient management process measures | Few or almost none | 1/3 to 1/2 | 2/3 or more |

| Multidisciplinary physician communication | |||

| Share of patients for whom you discussed treatment plan with a… | |||

| Medical oncologist prior to surgery | 31.4 | 35.3 | 33.3 |

| radiation oncologist prior to surgery | 43.4 | 31.4 | 24.2 |

| plastic surgeon prior to surgery | 43.8 | 43.2 | 13.0 |

| Availability of clinical information | |||

| Share of patients who came for second opinion for whom you… | |||

| had specimens that were collected by another provider reviewed again by your pathologist | 53.3 | 14.5 | 32.2 |

| had mammogram images that were taken at another institution reviewed again by your radiologist | 26.3 | 25.7 | 48.0 |

| repeated mammogram images that were brought from another institution | 58.0 | 32.1 | 9.8 |

| Patient decision support | |||

| Share of patients who… | |||

| attended presentation about breast cancer organized by your practice | 71.0 | 10.8 | 18.2 |

| viewed video about tx issues made available through your practice | 77.4 | 7.4 | 15.2 |

| were referred to website tailored to your practice | 75.3 | 18.5 | 6.2 |

| attended a patient support group organized by your practice | 72.2 | 14.2 | 13.6 |

| talked to other patients arranged by your practice | 69.0 | 24.8 | 6.2 |

Additional questions in the survey included surgeons' professional and personal characteristics (years in practice and gender); practice characteristics including the level of specialization (% of total practice devoted to breast cancer), teaching status (presence of surgical residents or surgical oncology fellow in the practice), and practice program affiliation (National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center, American College of Surgeons Cancer Program, or neither).

Analysis

We first described characteristics of the surgeon study sample. Next, we described the distribution of responses to the individual items within each scale and the distribution of the scale scores. We then evaluated the validity of a scale score by comparing surgeons' responses to the items pertaining to multidisciplinary physician communication to their patients' report of their experiences. For this component of the analysis only, we used a dataset containing information from patient surveys described above that was matched and merged to attending surgeon respondents. The merged dataset contained 1764 respondent patients nested within 290 respondent surgeons. Finally, we used the surgeon dataset to evaluate correlates of patient and practice management processes. We used separate models to regress the three continuous measures of patient management processes using OLS regression. We used ordinal logistic regression to evaluate the association of the two ordinal measures of practice management with selected surgeon and practice characteristics. All models contained the same covariates: number of years in practice (continuous), gender, practice specialization (% of total practice devoted to breast cancer- ≤ 15%, 15%-49%, 50% or greater), cancer program affiliation (none, ACoS Cancer Program, NCI center), and teaching program status. One model (for the dependent variable availability of clinical information) also included an ordinal covariate that measured the surgeon's report of the percent of newly-diagnosed patients with breast cancer in the prior year that came for a second opinion.

Results

Surgeon characteristics

Surgeons practiced an average of 18.5 years since completing training. About one-fifth of the surgeons (17.5%) were female. About half of the surgeons (46.1%) devoted less than or equal to 15% of their total practice to breast cancer, 16.2% of surgeons devoted 50% or more, and 37.7% devoted between 15%-50%. About one-third (29.2%) worked in a practice affiliated with an NCI comprehensive cancer center, 40.1% were affiliated with a program approved by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, and 30.8% were in practices not affiliated with either of these programs. Finally, 48.1% were practicing in teaching programs.

Distribution of item responses for each patient and practice management process measure

Table 1 shows the distribution of surgeon responses to each item related to the patient management process measures. There was a fairly large distribution of responses which were skewed towards the lower end of the response category representing a lower share of patients. For example, for items pertaining to multidisciplinary physician communication, about a quarter to one-third of surgeons reported that they discussed the treatment plan with medical and radiation oncologists prior to surgery for a majority of their patients treated in the prior 12 months. Communication with plastic surgeons prior to surgery was much less common. For the scale pertaining to the availability of clinical information at the time of consultation, a substantial proportion of surgeons reported that they frequently had outside pathology or imaging studies reviewed again by their colleagues (two-thirds or more of their patients). About two-thirds of surgeons reported that few or almost none of their patients participated in patient decision support activities arranged by the practice such as attending a practice-based presentation, viewing web based materials, or peer support programs.

Table 2 shows surgeon responses to each item related to the two practice management process measures: access to clinical information system and practice feedback. About three-quarters of surgeons had access to an online medical record system for clinical results, 55.5% had access to online physician notes, and 39.2% had access to an order entry system. About half of surgeons were in a practice that collected information and provided feedback about clinical management and quality issues. About one-third were in practices that were involved in a regional network.

Table 2. Surgeon responses to each item relate to the practice management process measures (N=318).

| %1 | |

|---|---|

|

Clinical Information Systems In the past 12 months did you have access to… |

|

| an online medical record system for clinical test results? | 76.6 |

| an online medical record system for physician notes? | 55.5 |

| an online orders entry system? | 39.2 |

|

Practice Feedback Does your practice… |

|

| collect information about patients for purposes of quality of care? | 45.7 |

| provide feedback to its clinicians about meeting clinical management standards? | 55.0 |

| participate in a practice network that is used to examine variations in treatment? | 32.2 |

Percent of respondents who endorsed the given item

Distribution of patient and practice management process measure scores

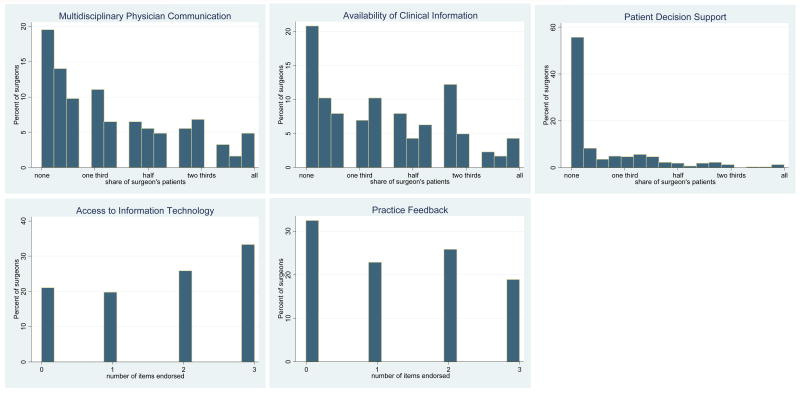

Figure 1 shows the percent distribution of the patient and practice process scores for each measure. For example, the first exhibit in the top row shows that about 40% of surgeons had scores less than 2 on the five-point scale, indicating that a low proportion of their patients were exposed to multidisciplinary physician communication prior to surgery. Only about 10% of surgeons scored higher than 4, indicating that a high proportion of patients were exposed to this communication process. Access to clinical information scores were similarly skewed towards the low end of the scale: 44.2% of surgeons had scores below 2, while 9.0% had scores above 4. Patient decision and care support was the least frequently endorsed practice process measure. Over half of the surgeons reported that few of their patients received these services while only 5% had scores above 3, indicating that half of their patients were provided these services. The distribution of access to information technology and practice feedback score measures was quite uniform. About one-third of surgeons reported access to all elements of online medical record data, and about one-fifth of surgeons reported that their practice had practice feedback and participated in regional networks.

Figure 1.

The figures show the distribution of surgeon scores for each of the five patient and practice management measures. The x-axis scale values for the communication, information, and support variables are the share of individual surgeon's patients (averaged across the items in each scale) who received the given practice process (interval measure from 1 none or very few patients to 5 almost all patients); the x-axis values for the information technology and feedback variables indicate the number of items in each scale endorsed by surgeons (totaling up to 3).

Validation of surgeon report of multidisciplinary physician communication

Table 3 shows the association of surgeon report of multidisciplinary physician communication prior to surgery with patient report of whether they consulted with a given specialist prior to surgery. Surgeon report of more multidisciplinary physician communication was strongly and positively correlated with patient report of consulting these physicians prior to surgery. For example, only 22.9% of patients consulted with a radiation oncologist before surgery in practices where surgeons reported that generally they have a pre-operative consult with radiation oncologists for few or none of their patients; while 71.9% of patients reported a consult with a radiation oncologist prior to surgery in practices where surgeons reported that they generally have a pre-operative consult with a radiation oncologist for more than half of their patients.

Table 3. Distribution Of Patient Responses By Items In The Multidisciplinary Physician Communication Scale.

| Surgeon survey items | % of patients who reported that they consulted with given specialist prior to surgery | |

|---|---|---|

| For how many patients did you consult with… | ||

|

| ||

| a medical oncologist prior to surgery2 | ||

| few or none | 21.0 | |

| 1/3 to ½ | 54.3 | |

| 2/3 or more | 72.4 | p<.001 |

|

| ||

| a radiation oncologist prior to surgery | ||

| few or none | 22.9 | |

| 1/3 to ½ | 40.1 | |

| 2/3 or more | 71.9 | p<.001 |

|

| ||

| a plastic surgeon prior to surgery3 | ||

| few or none | 28.4 | |

| 1/3 to ½ | 62.8 | |

| 2/3 or more | 77.0 | p<.001 |

N=1764 respondent patients merged with 290 respondent surgeons

For patients with invasive disease

For patients who received initial mastectomy

Correlates of patient and practice management process measures

Table 4 shows adjusted correlates of the patient and practice management process scales with selected surgeon characteristics. Columns 2-4 show OLS regression results for three continuous dependent variables that are based on the patient process measures with a range from 1 to 5. Columns 5 and 6 show ordinal logistic regression results for two dependent variables that are based on the two practice management process measures. These two variables are counts (endorsements of none, 1, 2, or 3 of the items for each delivery system factor). Teaching status was the most consistent correlate across the set of practice management process measures. The adjusted coefficient between teaching and non-teaching practices ranged from 1.61 (on a five-point scale) for the availability of clinical information to .46 for multidisciplinary physician communication. The adjusted odds ratios of higher counts of practice feedback and information support for teaching settings were 2.0 (95%CI 1.3, 3.0) and 2.1 (95%CI 1.4, 3.2), respectively. Greater surgeon specialization was positively associated with four of five patient and practice management process measures. By contrast, practice program affiliation was quite weakly associated with these measures.

Table 4. Correlates of Patient and Practice Management Process Scores.

| Characteristics | Md physician communication2 | Availability of clinical info2 | Patient Support2 | Practice feedback3 | Access to Info tech3,5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff (se) | Coeff (se) | Coeff (se) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

|

| |||||

| Specialization | |||||

| ≤15% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 15-49% | -.04 (.16) | .46 (.143) | .321 (.110) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.3) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) |

| ≥50% | .19 (.23) | 1.11 (.219) | .642 (.166) | 4.4 (2.2, 9.0) | 1.8 (0.9, 3.5) |

| F/Wald test, p value | .52, .596 | 13.69, p<.001 | 8.70, <.001 | 19.18, p<.001 | 5.58, p=.061 |

|

| |||||

| Cancer program | |||||

| None | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| ACoS | .19 (.166) | .02 (.154) | -.09 (.119) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) |

| NCI | .43 (.183) | .11 (.169) | -.25 (.131) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.1) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.2) |

| F/Wald test, p value | 3.0, .041 | .22, .806 | 1.89, .153 | 6.00, .049 | 0.94, .626 |

|

| |||||

| Teaching program | .46 (.140)* | 1.61 (.20)* | .29 (.10)* | 2.0 (1.3, 3.0) | 2.1 (1.4, 3.2) |

all values are adjusted for variables in the table, surgeon gender, and years in practice

interval dependent variable range 1.0 to 5.0

ordinal count range 0-3

p<.001

also controls for proportion of newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer seen for second opinion

To put these results in perspective, about one-third of surgeons (32.9%) in a practice with a teaching program reported that the majority of their patients received multidisciplinary physician communication vs. 16.5% of surgeon in non-teaching programs. About one-third of highest specialized surgeons practicing in teaching program (33.7%) reported that the majority of their patients received formal decision and care support vs. 5.4% of lowest specialized surgeons working in non-teaching settings; 85% of highest specialized surgeons working in practices with teaching programs reported that clinical information from other hospitals was reviewed in their institution for the majority of their patients vs. 13.7% of lowest specialized surgeons in practices without a teaching program.

Discussion

The Institute of Medicine has called for more coordinated cancer care models led by experienced professionals.1 These recommendations correspond to efforts by providers and professional organizations to improve cancer treatment decision making and delivery.2-5 These efforts parallel those underway to integrate the management of patients with chronic disorders based on the Chronic Care Model approach to reorganizing care.17, 18, 29 Informed by this Model, and the findings of our research team and others, we developed a set of breast cancer patient and practice management process measures. We then evaluated patterns and correlates of these measures in a sample of attending surgeons who treated a large population-based sample of patients recently diagnosed with breast cancer in the metropolitan areas of Detroit and Los Angeles. We found large variation in surgeon characteristics related to breast cancer practice specialization. There was also large variation in the extent of the use of patient and practice management processes with most surgeons reporting low use. For example, only about a third of surgeons reported a majority of their patients consulted with a multidisciplinary group of physicians prior to surgery. Only 9% reported that the majority of their patients received explicit decision and care support such as a formal presentation, audiovisual materials, or a patient support group. Patient and practice management process measures were moderately correlated with surgeon specialization and the presence of a teaching program. Cancer program affiliation was weakly associated with patient and practice management processes.

The low diffusion of these practice processes in breast cancer care may indicate that surgeons are not convinced that the activities included in these measures directly improve the quality of care. Indeed, none of the evidence currently demonstrating the effectiveness of these patient and practice management processes for improving quality care is from cancer care settings. Most review articles focused on cancer care have primarily presented reasons to support the use of these processes justified on conceptual and policy grounds.5, 11-13 The few published empirical studies have largely focused on the most easily measured attributes of physician practice such as patient volume or teaching status.6, 7 An extensive review of these studies in 2001 concluded that that there was reasonable evidence for a volume-health outcome relationship for high risk cancer surgery, but little evidence for such a relationship for lower risk surgery such as breast cancer.6 One breast cancer specific study showed that surgeon experience was associated with higher patient satisfaction with treatment decision making.21 Several studies suggested that preoperative consultation with specialists influences treatment decisions. 22, 30, 31 However, no rigorous studies have evaluated the potential impact of multidisciplinary care models on other cancer patient outcomes.9, 10 Thus, there may be little consensus among surgeons about the utility of preoperative consultation by different specialists for patients with breast cancer.

Another possible explanation for low uptake of patient and practice management processes is that logistical and cost barriers inhibit collaborative care models or patient decision and care support initiatives. Most surgeons in the sample devoted a low proportion of their practice to breast cancer. We found that surgeons in more specialized practices reported more collaborative communication and patient decision support. These surgeons may be more willing or have more opportunities to invest in infrastructure such as same day appointments, weekly tumor board and decision support activities. The many surgeons that devote a small proportion of their total practice to breast cancer may not feel that a large investment in infrastructure targeting patients with breast cancer is justified. Another possible explanation is that there is low demand for these practice initiatives by patients, especially those treated by less specialized surgeons. The presence of a teaching program also appears to be associated with collaborative communication and patient decision and care support initiatives independent of surgeon practice specialization. Practices that participate in surgical teaching programs may be more motivated to initiate innovations in practice, or these features may evolve more naturally due to the structure of teaching programs.

There are several strengths to the study. Attending surgeons were identified precisely using complementary data sources from a population-based sample of patients diagnosed in two large diverse urban areas. The surgeon and patient survey response rates were high. Validity of self-report in prior studies by our team show strong validity of surgeon report of their experience and specialization in breast cancer.19 In this study, we found that surgeon report of the extent of multidisciplinary physician communication was strongly correlated with patient report of their experiences. However, there are some limitations. We cannot generalize our findings to rural areas. Surgeon report of institutional program affiliation was problematic: about one third of respondents did not know whether their practice was affiliated with an institution designated as an NCI comprehensive cancer center, and 15% did not know whether their practice was approved by ACoS Commission on Cancer. Furthermore, these designations are made to hospitals and surgeons may practice in more than one facility. Misclassification may have minimized the observed association of cancer program status with practice process variables.

Implications for patient care

The results of the study should be cautiously interpreted with regard to patient care. One important caveat is that we do not know yet whether patients who received treatment from more experienced surgeons using more patient and practice management processes actually received better quality of care. More research is needed to understand if and how the large variation in patient and practice management processes we observed in this study affects the quality of care for patients with breast cancer including treatments received, patient satisfaction with decision and care issues, and quality of life. However, patients may not want to wait for the additional studies. Patients could target referral to surgeons specializing in breast cancer working in teaching settings if they wish to optimize the probability of being treated in a practice utilizing these management processes. Surgeons with fewer breast cancer cases may find it particularly challenging to adopt the patient and practice management processes we described in this study. These surgeons may benefit from more virtual approaches to decision support and communication such as computer-based decision and care support tools or internet-based methods for between-physician communication to facilitate their practice in breast cancer treatment. This is another promising area of research that may improve the quality of care for women with breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was funded by grants R01 CA109696 and R01 CA088370 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the University of Michigan. Dr. Katz was supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral, and Population Sciences Research from the NCI (K05CA111340). We thank the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons (Connie Bura and David Winchester M.D.) for their support of the study. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Health Services as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930 awarded to the Public Health Institute.

The collection of metropolitan Detroit cancer incidence data was supported by the NCI SEER Program contract N01-PC-35145. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Report. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. In: Hewitt M, Simone JV, editors. National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine Report and National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. p. 97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Accessed 2008];Quality of Care and Survivorship Issues. 2007 at http://ncccp.cancer.gov/Resources/QualityCare.htm.

- 3. [Accessed November, 2008];The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. 2008 2008, at http://qopi.asco.org.

- 4. [Accessed November, 2008];National Quality Forum Endorsed Commission on Cancer Measures for Quality of Cancer Care for Breast and Colorectal Cancers. 2007 2008, at http://www.facs.org/cancer/qualitymeasures.html.

- 5.Tripathy D. Multidisciplinary care for breast cancer: barriers and solutions. The Breast Journal. 2003;9:60–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillner BE, Smith RJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: Importance in quality of cancer care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:2327–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkmeyer JD. Undertanding Surgeon Performance and Improving Patient Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:2765–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waljee JF, Hawley ST, Alderman AK, Morrow M, Katz SJ. Patient satisfaction with the treatment of breast cancer: does surgeon specialization matter? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:3694–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houssami N, Sainsbury R. Breast cancer: multidisciplinary care and clinical outcomes. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42:2480–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Fallowfield L. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncology. 2006;7:935–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright FC, DeVito C, Langer B, Hunter A, et al. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: a systematic review and development of practice standards. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:1002–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim R, Toge T. Multidisciplinary approach to cancer treatment: a model for breast treatment at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9:356–63. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabinowitz B. Interdisciplinary breast cancer care: declaring and improving the standard. Oncology. 2004;18:1263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Accessed November, 2008];Cancer Program Approval. 1998 2008, at http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/whatis.html.

- 15.Kahn KL, Malin JL, Adams J, Ganz PA. Developing a reliable, valid and feasible plan for quality of care measurement for cancer. How should we measure? Med Care. 2002;40(Suppl):III-73–III-85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. [Accessed November, 2008];Improving Chronic Illness Care website. 1998 2008, at http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.html.

- 17.Casalino LP. Disease management and the organization of physician practice. JAMA. 2005;293:485–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner EH, Austin BT, VK M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. 1996;74:511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz SJ, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, Lantz PM, Janz NK, et al. Patterns and correlates of patient referral to surgeons for treatment of breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:271–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz SJ, Hawley S. From policy to patients and back: surgical treatment decision-making for patients with breast cancer. Hlth Affairs. 2007;26:761–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waljee JF, Hawley S, Alderman AK, Morrow M, Katz M. Surgeon specialization and patient satisfaction with breast cancer treatment. 2007 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9272. http://wwwascoorg/portal/site/ASCO/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hawley ST, Hofer TP, Janz NK, et al. Correlates of between-surgeon variation in breast cancer treatments. Medical Care. 2006;44:609–16. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215893.01968.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn KL, Malin JL, Adams J, Ganz PA. Developing a reliable, valid and feasible plan for quality of care measurement for cancer. How should we measure? Med Care. 2002;40(Suppl):III-73–III-85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton A, Hofer T, Hawley S, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population-based sampling, ethnic identity and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mujahid M, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, K SJ. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0389-y. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janz N, Mujahid M, Hawley S, Hamilton A, Katz S. Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:1058–67. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawley S, Hamilton A, Janz N, et al. Latina patient perspectives about informed decision making for surgical breast cancer treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 29. [Accessed November, 2008];Chronic Care Model Changes. 1998 2008, at http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/ChronicConditions/AllConditions/Changes.

- 30.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Winer EP, Guadagnoli E. Consultation with a medical oncologist before surgery and type of surgery among elderly women with early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:4532–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldwin LM, Taplin SH, Friedman H, Moe R. Access to multidisciplinary cancer care: is it linked to the use of breast-conserving surgery with radiation for early-stage breast carcinoma? Cancer. 2004;100:701–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]