Abstract

Survivin is a cancer-associated gene that functions to promote cell survival, cell division, and angiogenesis and is a marker of poor prognosis. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce apoptosis and re-expression of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells. In association with increased expression of the tumor suppressor gene transforming growth factor β receptor II (TGFβRII) induced by the histone deacetylase inhibitor belinostat, we observed repressed survivin expression. We investigated the molecular mechanisms involved in survivin down-regulation by belinostat downstream of reactivation of TGFβ signaling. We identified two mechanisms. At early time points, survivin protein half-life was decreased with its proteasomal degradation. We observed that belinostat activated protein kinase A at early time points in a TGFβ signaling-dependent mechanism. After longer times (48 h), survivin mRNA was also decreased by belinostat. We made the novel observation that belinostat mediated cell death through the TGFβ/protein kinase A signaling pathway. Induction of TGFβRII with concomitant survivin repression may represent a significant mechanism in the anticancer effects of this drug. Therefore, patient populations exhibiting high survivin expression with epigenetically silenced TGFβRII might potentially benefit from the use of this histone deacetylase inhibitor.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Histone Deacetylase, Proteasome, Protein Kinase A (PKA), Transforming Growth Factor β (TGFβ), Cell Death, Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors, Survivin, TGFβ Receptor Type II

Introduction

The mutational events involved in the initiation and progression of colorectal cancer have been well documented (1). However, it is now recognized that in addition to these alterations in DNA sequence epigenetic modifications of the genome play a major role in contributing to the malignant phenotype (1, 2). The critical balance between histone acetylation by histone acetyltransferases and deacetylation by histone deacetylases (HDACs)3 represents a key epigenetic layer involved in gene regulation (3). The class I HDACs are overexpressed in many tumor types compared with normal tissues (4), and this overexpression is generally associated with poor prognosis (5, 6). These findings have resulted in the development of drugs that target HDACs. The second generation HDAC inhibitors (HDACis) target class I and II HDACs. These drugs induce differentiation, cell growth arrest, and apoptosis in cell lines in vitro and in vivo indicating that the increased activity of these enzymes in cancer contributes to tumor progression (7–9). However, the key mechanisms and pathways through which HDAC inhibition leads to tumor cell apoptosis have not been well defined.

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling has been shown to contribute to a variety of cellular functions including growth inhibition and induction of differentiation and apoptosis as well as cell motility and adhesion (10). It has been demonstrated that transcriptional loss of TGFβ receptor expression leading to attenuation of TGFβ signaling is a frequent occurrence in a wide range of cancers in vitro and in vivo and is associated with poor patient prognosis (11–22).

We demonstrated that the HDACi suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) restored TGFβ signaling in breast cancer cell lines through induction of the TGFβ receptor type I (TGFβRI; Ref. 16). The HDACi trichostatin A (TSA) activated TGFβRII promoter activity of epigenetically silenced TGFβRII (23). Furthermore, we reported that TGFβ signaling decreases survivin expression in colon cancer cells in response to stress (24).

Belinostat is a member of the hydroxamate class of HDACis with reported activity against a variety of human cell lines in vitro and in vivo (25). It is in clinical trials against both hematological and solid tumors. Therefore, we determined whether the drug induces re-expression of TGFβRII with concurrent restoration of the downstream effects of TGFβ signaling in colon, breast, and pancreatic cancer cells with epigenetically silenced TGFβ receptor. Furthermore, we examined the mechanism by which belinostat-mediated reactivation of TGFβ signaling leads to cancer cell death.

We report the identification of belinostat-mediated induction of a novel TGFβ/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway leading to survivin down-regulation. Additionally, we report the identification of dual mechanisms involved in this TGFβ-dependent down-regulation of survivin induced by belinostat. The early repression of survivin is mediated by proteasomal degradation, whereas the late suppression involves transcriptional repression of survivin expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

The FET, CBS, and GEO colon carcinoma cells were cultured in a serum-free medium as described previously (26). The FET dominant negative TGFβRII (designated FETDNRII) cells were obtained by stable transfection of a TGFβRII construct lacking the serine/threonine kinase domain and most of the carboxyl terminus (the cytoplasmic domain) into FET colon carcinoma cells as described previously (24). The MCF-7L breast cancer cell line was maintained in supplemented McCoy's 5A supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cellgro, Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA; Ref. 27). The MiaPaCa2 pancreatic cancer cell line was obtained from Dr. Jim Freeman (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX). It was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cellgro, Mediatech, Inc.).

Pharmacological Inhibitors

Belinostat and TSA were obtained from Topotarget and Sigma, respectively. The TGFβRI kinase inhibitor ALK5 inhibitor I (ALK5i) was obtained from Calbiochem.

Antibodies

Survivin, TGFβRII, p21, p15, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The phospho-Smad2 (Ser465/467) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Cleaved caspase 9 was purchased from Millipore. Anti-actin was purchased from Sigma.

shRNA Knockdown Studies

Smad2 shRNA (catalogue number sc-38378-SH) and PKA Catα shRNA (catalogue number sc-36240-SH) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. FET cells were seeded into 10-cm dishes. At about 40% confluence, the serum-free medium was replaced with Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). The cells were transfected with a pool of three shRNAs targeted against the human PKA Catα subunit or Smad2 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Control shRNA plasmid A (catalogue number sc-108060) was used as a negative control. Three stable clones were selected for the study. Representative data are shown here.

siRNA Knockdown Studies

Individual Smad2 siRNAs A and B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. catalogue numbers sc-38374A and sc-38374B) were transiently transfected in FET cells at 40% confluence. Control siRNA plasmid A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. catalogue number sc-37007) was used as a negative control. Transient transfections were done according to the manufacturer's protocol.

PKA Catalytic α Plasmid for Restoration Studies

The PKA catalytic α subunit plasmid construct was obtained from Susan Taylor's laboratory at University of California, San Francisco (supplied by Addgene; plasmid 14921, pET15b PKA Catα). The plasmid was transiently transfected into FETPKACatα KD cells using FuGENE HD transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Western Blots

Cells were lysed with TNESV lysis buffer (50 mmol/liter Tris (ph 7.5), 150 mmol/liter NaCl, 1% NP40, 50 mmol/liter NaF, 1 mmol/liter Na3VO4, 25 μg/ml β-glycerophosphate, 1 mmol/liter phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN)), as described previously (28). Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). Protein (30–100 μg) was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences) by electroblotting. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST according to the antibody data sheets. After washing with TBST for 10 min, the membrane was incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies, and proteins were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real Time PCR

RNA was collected from treated cells using the High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The two-step quantitative PCR using TaqMan reagents was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems). The mRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH.

DNA Fragmentation Assay

The DNA fragmentation assay was performed using a cell death ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The plate was read at 405 nm. Another set of treated cells was stained with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma) as described previously (28) for measuring the inhibition of cell proliferation. The plate was read at 570 nm.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were grown on poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips suitable for immunofluorescence microscopy as described previously (29). The cell staining was visualized with a Leica DMRIE microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzler, Germany) equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu City, Japan). The cell images were collected and analyzed using the image-processing software Openlab 4.0 (Improvision, Boston, MA).

Proteasomal Activity Assay

FET cells were plated at 800,000 cells/10-cm dish in serum-free medium (26). On day 5, cells were treated with belinostat (500 nm) for different time points and harvested for proteasomal activity assay in proteasomal assay buffer (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100 containing 2 mm ATP). The fluorometric proteasome substrate III for chymotrypsin (succinyl-LLVY-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin) was obtained from Calbiochem. After quantification of protein concentration, cell lysates were incubated with the chymotrypsin substrate for 1 h at 37 °C, and the amount of chymotrypsin substrate cleavage was quantified fluorometrically (30).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. Differences between groups were tested for statistical significance by using one-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism 4 software. Only p values <0.05 were considered significant. All experiments were repeated three times independently.

RESULTS

TGFβRII Induction in Belinostat-treated Cells

We first assessed the ability of belinostat to regulate TGFβRII expression in the TGFβ-sensitive FET colon carcinoma cell line, which expresses type II TGFβ receptor and retains the tumor suppressor effects of TGFβ (24). As shown in Fig. 1A, belinostat treatment increased both TGFβRII mRNA and protein expression at 48 h in a concentration-dependent manner. Having established that belinostat treatment is functionally effective in regulating TGFβRII expression in TGFβ-sensitive cells, we next assessed the effect of belinostat on different cancer cell lines with known epigenetic silencing of TGFβRII. Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated TGFβRII epigenetic silencing in MCF-7L and the MiaPaCa2 pancreatic cell line (13, 17). Belinostat treatment reactivated TGFβRII mRNA and protein expression in both of these cell lines (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1A). We determined whether belinostat treatment can alter TGFβRII levels in cancer cell lines in which TGFβRII is not known to be epigenetically regulated and does not respond to HDAC inhibitors (63). We used the Panc1 pancreatic cancer cell line in these experiments. Panc1 cells showed no protein expression of TGFβRII, and treatment with belinostat was unable to increase its protein expression (supplemental Fig. S1C). To confirm that this reactivation was an effect of HDAC inhibition, we tested the effect of TSA on TGFβRII expression in these cell lines. Indeed, TSA treatment of MCF-7L cells resulted in re-expression of TGFβRII mRNA and protein (Fig. 1C). We also confirmed that belinostat reconstituted TGFβRII protein expression in a colon cancer cell line, CBS, that has been demonstrated to have attenuated TGFβ signaling (26). Belinostat treatment of TGFβRII-deficient CBS colon cancer cells again resulted in the induction of TGFβRII mRNA and protein expression (supplemental Fig. S1B). These data demonstrate that belinostat treatment is able to restore TGFβRII transcription, which results in reconstitution of the TGFβRII receptor protein.

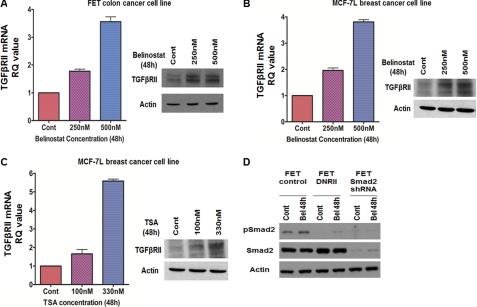

FIGURE 1.

TGFβRII induction in belinostat-treated cells. Concentration-dependent induction of TGFβRII mRNA and protein expression in FET (A) and MCF-7L (B) cells treated with belinostat for 48 h is shown. Concentration-dependent induction of TGFβRII mRNA and protein expression in MCF-7L cells treated with TSA for 48 h (C) is shown. The mRNA results are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Error bars indicate S.E. Belinostat treatment for 48 h induced phospho-Smad2 (pSmad2) in FET cells (D). No phospho-Smad2 induction was observed in FET Smad2KD and FETDNRII cells. Actin was used as loading control for Western blots. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cont, control; RQ, relative quantity; Bel, belinostat.

TGFβ Signaling-dependent Cell Cycle Arrest in Belinostat-treated Cells

The ability of HDACi to inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis indicates the critical role of HDACs in these processes (31, 32). Although TGFβRII epigenetic silencing has been extensively characterized and the reversion of transcriptional silencing by HDACi has been documented, its involvement in HDACi-mediated cell death has not been tested. We hypothesized that belinostat treatment mediates cell death through the TGFβ pathway. We reasoned that belinostat-mediated induction of TGFβRII might reactivate the TGFβ signaling pathway leading to the restoration of the growth-inhibitory and cell death effects of TGFβ signaling on inappropriate cell survival pathways. To test whether belinostat restores TGFβ signaling, we first investigated the ability of belinostat to induce Smad activation, which is a hallmark of canonical TGFβ-Smad signaling downstream of TGFβ receptor activation (33). Belinostat treatment resulted in phosphorylation of Smad2 in FET cells (Fig. 1D). To evaluate the dependence of TGFβ receptor signaling on Smad activation, we utilized the FETDNRII cells with abrogated TGFβ signaling due to transfection of a dominant negative TGFβRII vector construct (24). Belinostat-mediated activation of Smad2 was completely abrogated in the FETDNRII cell line indicating that Smad activation is downstream of belinostat-mediated TGFβRII induction (Fig. 1D).

Having established that belinostat mediates restoration of TGFβ receptor signaling leading to Smad activation, we investigated the role of this reconstituted TGFβ signaling in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Although HDACi-mediated restoration of transcription of epigenetically silenced TGFβRII has been well documented, the specific contribution of the ensuing TGFβ-Smad signaling to the HDACi-mediated cell cycle arrest and/or apoptotic cell death has not been demonstrated. We first tested the potential role of belinostat-mediated restoration of TGFβ signaling in the induction of cell cycle arrest by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 2A). We observed a TGFβ signaling-dependent increase in the G2-M phase following belinostat treatment. The expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) p21WAF1/CIP1 has been shown to be induced in transformed cells by the HDACis phenylbutyrate, SAHA, and TSA and is associated with G1 phase cell cycle arrest (9, 34). Furthermore, it has also been reported that another CDKI, p15(INK4b), is induced by the HDACis TSA and sodium butyrate in colon cancer cells (35). Previous work from our laboratory has shown that MCF-7L cells stably transfected with TGFβRII show inhibition of xenograft growth in association with the enhanced growth arrest resulting from p21WAF1/CIP1 induced by endogenous TGFβ signaling (27). The reconstitution of TGFβ signaling in the highly tumorigenic GEO cell line by stable transfection of TGFβRI also results in cell cycle arrest mediated by p21WAF1/CIP1 induction (36). The TGFβ signaling pathway also mediates induction of p15(INK4b) as another growth arrest mechanism (37). Therefore, we determined whether belinostat induced expression of these CDKIs and whether this effect was downstream of reconstitution of TGFβ signaling. Immunohistochemical and Western blot analyses revealed that belinostat induced increased expression of both p21WAF1/CIP1 and p15(INK4b) in MCF-7L cells (Fig. 2, B and C) in line with previous reports on the effects of HDACis. To test whether TGFβ signaling was involved in this belinostat-mediated effect on CDKIs, MCF-7L cells were pretreated with the TGFβRI inhibitor ALK5i prior to treatment with the HDACi. Inhibition of the TGFβ signaling pathway partially attenuated the induction of both p21WAF1/CIP1 and p15(INK4b) supporting the hypothesis that belinostat mediates cell cycle arrest through reconstitution of TGFβ signaling. To independently validate these results, we confirmed that belinostat treatment induced p21WAF1/CIP1 induction in the TGFβ-sensitive FET cells (Fig. 1D). It has been reported that TGFβ up-regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 leading to cell cycle arrest is mediated by Smad activation. There are Smad binding sites within the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter (38). To determine whether the Smads mediated belinostat-induced cell cycle arrest through TGFβ signaling restoration, we utilized Smad2 knockdown in the FET cell line (designated FETSmad2 KD cells). Belinostat treatment of these Smad2 KD cells did not lead to p21WAF1/CIP1 induction (Fig. 1D) confirming the signaling intermediate role of the Smads in belinostat induction of cell cycle arrest. Therefore, HDACi belinostat-mediated induction of CDKIs is linked to TGFβ signaling.

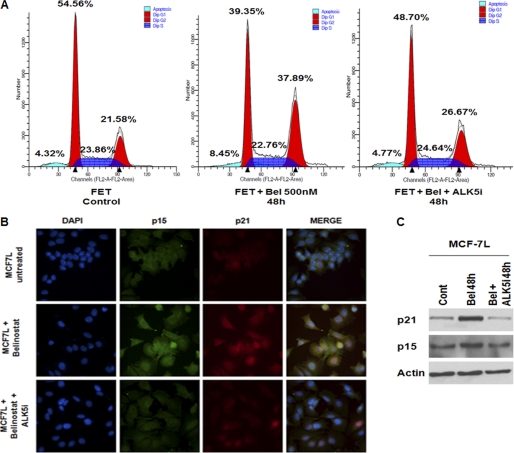

FIGURE 2.

TGFβ signaling-dependent cell cycle arrest in belinostat-treated cells. Cell cycle analysis of FET cells treated with belinostat (500 nm) ± ALK5i for 48 h by FACS (A) is shown. MC7–7L cells were treated with belinostat (500 nm) ± ALK5i for 48 h to determine effects on cell cycle arrest. Immunofluorescence imaging using confocal microscopy and immunoblotting of p21 and p15 were performed to show the induction of cell cycle inhibitors (B and C). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cont, control; Bel, belinostat.

Role of TGFβ in Belinostat-mediated Apoptosis

We next determined whether the apoptotic response to belinostat was mediated through induction of TGFβ signaling. HDACi treatment has been shown to selectively induce tumor cell death along with cell cycle arrest (7). As shown in Fig. 3A, belinostat treatment showed a time-dependent increase in apoptotic cell death in all cancer cell lines tested. To begin to study the role of reactivation of TGFβ signaling in belinostat-induced apoptosis, we first studied the effect of belinostat in the FET colon carcinoma cell line FETDNRII. Abrogation of TGFβ signaling resulted in a decreased apoptotic response in these cells compared with the parental cell line (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained from using ALK5i pretreatment prior to belinostat treatment of FET cells as well as belinostat treatment of FETSmad2 KD cells (supplemental Fig. S2A). We performed flow cytometry analysis and stained for Annexin V (Fig. 3, D and E). We observed an increase in apoptosis with belinostat treatment. These data provide evidence that TGFβ signaling contributes to the apoptotic response induced by belinostat. It has been reported that the apoptotic response to HDACi is accompanied by the cleavage of PARP and procaspases 3 and 9 (39–41). Therefore, we determined whether abrogation of TGFβ signaling would affect the cleavage of these apoptotic markers in response to belinostat. As shown in Fig. 3C, belinostat treatment induced cleavage of procaspase 9 in a concentration-dependent manner in FET cells. However, this effect was abrogated in FETDNRII cells providing further evidence that the apoptotic response to belinostat is mediated by TGFβ signaling.

FIGURE 3.

TGFβ signaling-dependent apoptosis in belinostat-treated cells. DNA fragmentation assays of different cell lines treated with belinostat (500 nm) for 24–48 h (A and B) are shown. The results are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Error bars indicate S.E. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the concentration dependence of belinostat (48 h) on caspase 9 cleavage in FET and FETDNRII cells (C). Actin was used as a loading control for Western blots. Cell apoptosis was determined by Annexin V staining and measured by flow cytometry analysis in FET and MCF-7L cells treated with belinostat ± ALK5i for 48 h (D and E). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cont, control; Cl., cleaved; Bel, belinostat.

As reported above, FET cells retain a low level of TGFβ signaling and therefore would be expected to be sensitive to the apoptotic effect of TGFβ. Therefore, we examined whether this TGFβ signaling had a role in the apoptotic response to belinostat in the cell lines in which the HDACi reactivated expression of epigenetically silenced TGFβRII. PARP is a substrate for caspases activated during early stages of apoptosis and serves as an early marker of apoptosis (42). We observed induction of both cleaved caspase 9 and PARP by immunochemistry in belinostat-treated MCF-7L cells (supplemental Fig. S2B). Furthermore, pretreatment with the ALK5i prior to belinostat treatment repressed the induction of both cleaved caspase 9 and PARP by belinostat again establishing a role of TGFβ signaling in the belinostat treatment-mediated apoptotic cell death response following induction of expression of the TGFβRII tumor suppressor gene.

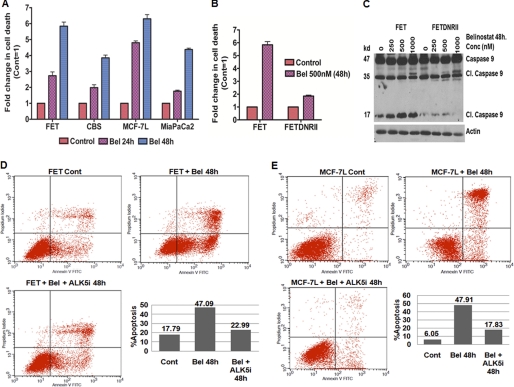

Belinostat Treatment Induces TGFβ Signaling-dependent Survivin Down-regulation

To gain further insight into the mechanisms relevant for belinostat treatment-induced cell death, we focused our attention on the expression of the IAP protein survivin (43). Previous work from our laboratory has shown that TGFβ signaling leads to cell death in colon cancer cells in vitro in response to stress in association with inhibition of survivin (24). A previous report has also implicated HDACi in survivin down-regulation (44). Given the widespread role of survivin in cell survival and cancer progression (24, 43, 45–47), we hypothesized that belinostat down-regulates the expression of survivin leading to the inhibition of aberrant cell survival. As shown in Fig. 4A, belinostat treatment decreased survivin mRNA and protein levels thus confirming the hypothesis. A similar response was obtained with belinostat treatment on several other cancer cell lines (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. S3, B and C). Furthermore, another HDACi, TSA, also repressed survivin expression in a manner similar to that of belinostat (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S3A). Interestingly, belinostat treatment of Panc1 cells (without TGFβRII up-regulation) was unable to induce survivin down-regulation as shown in supplemental Fig. S1C.

FIGURE 4.

Belinostat treatment induces TGFβ signaling-dependent survivin down-regulation. Concentration-dependent degradation of survivin mRNA and protein expression in FET (A) and MCF-7L (B) cells treated with belinostat for 48 h is shown. Concentration-dependent inhibition of survivin mRNA and protein expression in MCF-7L cells treated with TSA for 48 h (C) is shown. The mRNA results are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Error bars indicate S.E. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the concentration-dependent effects of belinostat (48 h) on survivin in FET and FETDNRII cells (D). Two independent FET cell lines in which Smad2 was knocked down by siRNAs (FETSmad2 siRNA A and B cells, respectively) were treated with belinostat and probed for survivin expression by Western blot (E). Actin was used as a loading control for Western blots. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cont, control; RQ, relative quantity; Bel, belinostat; pSmad2, phospho-Smad2.

These results implicated the TGFβ pathway in survivin repression. We hypothesized that belinostat acts through the TGFβ pathway in inducing survivin down-regulation. We confirmed the dependence on TGFβ signaling in the belinostat-mediated survivin down-regulation using FETDNRII cells. As shown in Fig. 4D and supplemental Fig. S3D, belinostat treatment of these cells had minimal effect on the survivin mRNA and protein levels indicating that belinostat regulates survivin through the TGFβ pathway. Furthermore, ALK5i pretreatment also rescued belinostat-mediated survivin loss (supplemental Fig. S3, E and F). Additionally, belinostat-mediated survivin down-regulation was completely abrogated in Smad2 KD cells (Fig. 4E). Individual Smad2 siRNAs were used for this knockdown study. Both Smad2 siRNAs A and B were able to abrogate the belinostat-mediated survivin degradation in these cell lines. These lines of evidence strongly support the hypothesis that belinostat treatment down-regulates survivin through the TGFβ signaling downstream of TGFβ receptor restoration.

Belinostat Treatment Decreases Survivin Protein Half-life

Earlier reports have shown that cycloheximide (CHX) degrades survivin protein in 293 cells within 3 h (48). We hypothesized that belinostat treatment alters the stability of survivin protein in mediating the early response. We tested the survivin protein half-life in FET cells with CHX treatment, and as shown in Fig. 5A (upper panel), survivin protein half-life was ∼2 h. Earlier reports have shown that in normal rat gastric mucosal RGM-1 cells survivin half-life is ∼1.5 h (48) confirming the short half-life of survivin protein. It has been shown that indomethacin treatment in RGM-1 cells prior to CHX treatment alters the survivin half-life in these cells. Based on this background, FET cells pretreated with belinostat for 1 h prior to CHX treatment showed a decrease in survivin protein half-life to ∼1 h (Fig. 5A, lower panel) indicating that survivin protein degradation is enhanced following belinostat treatment possibly by the accelerated degradation through the proteasome.

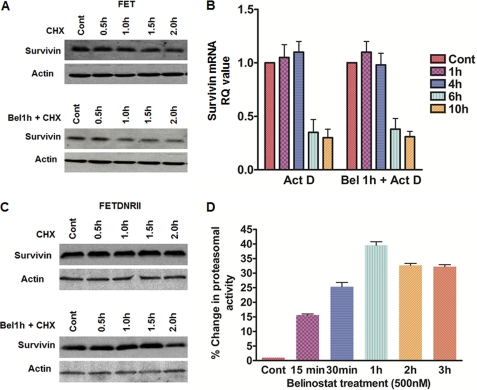

FIGURE 5.

Belinostat treatment decreases survivin protein half-life. FET cells were treated with 100 μg/ml CHX or pretreated with 500 nm belinostat 1 h prior to CHX treatment for the indicated times followed by determination of survivin protein levels (A). FET cells were treated with 10 μg/ml actinomycin D (Act D) or pretreated with 500 nm belinostat prior to actinomycin D treatment for the indicated times followed by determination of survivin mRNA levels (B). FETDNRII cells with abrogated TGFβ signaling were treated with 100 μg/ml CHX or pretreated with 500 nm belinostat prior to CHX treatment for the indicated times, and survivin protein levels were determined to show TGFβ signaling-dependent belinostat-induced changes in survivin half-life (C). Actin was used as a loading control for Western blots. FET cells were treated with belinostat (500 nm) for the indicated times, and proteasomal activity assays were performed (as described under “Experimental Procedures”) to determine the chymotrypsin activity of the proteasome following belinostat treatment (D). Error bars indicate S.E. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cont, control; RQ, relative quantity; Bel, belinostat.

The current study as well as other reports indicated that treatments directed toward survivin degradation at early time points (0–6 h) specifically alter survivin protein (48, 49). We hypothesized that the survivin transcript half-life is not altered following belinostat treatment at early time points. Actinomycin D treatment to stop transcription (50) in FET cells showed the survivin mRNA half-life to be ∼6 h (Fig. 5B). However, survivin mRNA half-life remained unchanged with belinostat pretreatment prior to actinomycin D treatment in these cells confirming the hypothesis that survivin mRNA is very stable at these time points. These lines of evidence indicate that belinostat treatment mediates post-translational control of survivin expression at early times after exposure to drug and transcriptional control at late times in the induction of survivin down-regulation.

Based on the dependence of TGFβ signaling on belinostat-mediated survivin down-regulation, we hypothesized that the belinostat treatment-mediated alteration of survivin half-life is dependent on the TGFβ signaling. To that end, FETDNRII cells in which survivin protein was stable up to 2 h following CHX treatment did not show a robust change in stability when pretreated with belinostat (Fig. 5C) confirming the hypothesis that belinostat mediates its effects through the TGFβ signaling-dependent mechanism.

Although our data supported the notion that belinostat accelerated the degradation of survivin protein, the mechanism by which survivin protein degradation through the proteasome is enhanced remained unclear. We hypothesized that belinostat increases intrinsic proteasomal activity and thereby accelerates survivin degradation. The proteasome is a proteolytic complex that degrades intracellular ubiquitinated proteins involved in apoptosis and cell cycle regulation. Heider et al. (30) demonstrated that treatment with a combination of SAHA and bortezomib (a proteasome inhibitor in clinical trial) for 24 h resulted in a stronger inhibition of proteasomal activity than with bortezomib alone. We tested the effect of belinostat treatment on proteasomal activity at 24 h in FET cells and found responses similar to those observed by Heider et al. (30) (data not shown). As belinostat treatment alters survivin protein half-life from ∼2 to 1 h at early time points, we hypothesized that belinostat alters the intrinsic proteasomal activity at these early time points to accelerate survivin degradation. Interestingly, belinostat treatment increased the proteasomal activity by ∼40% after 1 h of treatment (Fig. 5D). This increase in proteasome activity correlates with the accelerated degradation of survivin and its change in half-life by ∼1 h. We speculate that this increase in proteasomal activity might contribute to the belinostat-mediated survivin loss at early times. Taken together, we observed that belinostat was able to modulate both the survivin protein and the proteasome at early times.

Proteasomal Degradation of Survivin as Early Response to Belinostat Treatment

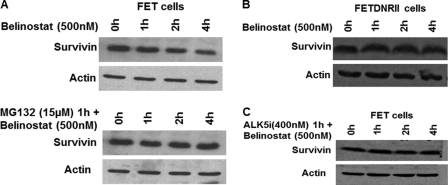

Chiou and Mandayam (48) showed that treatment with indomethacin alters survivin protein at early times without affecting the mRNA expression. Based on that background, we tested the effect of belinostat on survivin expression at early time points. It was observed that survivin protein was down-regulated as early as 4 h following belinostat treatment of the cells (Fig. 6A, upper panel). However, at early time points following belinostat treatment, mRNA expression was not repressed (data not shown) indicating that the belinostat treatment-mediated early effects on survivin are possibly due to post-translational mechanisms. The loss of the survivin mRNA at 24–48 h provides evidence that repression of transcription accounts for the late repression of the survivin response to belinostat. This indicates dual mechanisms of survivin down-regulation involving the survivin protein and RNA at different time points.

FIGURE 6.

Proteasomal degradation of survivin as early response to belinostat treatment. FET cells were treated with belinostat (500 nm) for the indicated times or pretreated with proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (15 μm) for 1 h prior to belinostat (500 nm) treatment, and survivin protein levels were determined (A). FETDNRII cells were treated with belinostat (500 nm) for the indicated times, and survivin protein levels were determined (B). Early loss of survivin by belinostat treatment was mediated through the proteasome in a TGFβ signaling-dependent manner. FET cells were treated with belinostat (500 nm) for the indicated times or pretreated with TGFβRI inhibitor ALK5i (400 nm) for 1 h prior to belinostat (500 nm) treatment, and survivin protein levels were determined (C). Abrogation of TGFβ signaling inhibits belinostat-mediated proteasomal degradation of survivin at early time points. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Previous reports have indicated that cell cycle effects on survivin degradation are mediated through the ubiquitin proteasomal pathway in a cell cycle-dependent manner (48). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that belinostat treatment at early time points mediates survivin protein degradation through the proteasome. To test whether proteasomal degradation was involved in the early repression of survivin, we treated FET cells with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 for 1 h prior to belinostat. Pretreatment with MG132 completely abrogated the belinostat-mediated survivin degradation at early times (Fig. 6A, lower panel).

Previous work from Brattain and co-workers (24) has shown that TGFβ signaling mediates survivin loss at late times. We next examined whether TGFβ signaling played a role in the early effect of Belinostat treatment on cancer cells. Belinostat treatment for short times had no effect on survivin protein levels in FETDNRII cells (Fig. 6B). Additionally, pretreatment of FET cells with ALK5i abrogated belinostat-mediated survivin degradation at early times confirming that belinostat exerts its early effects on survivin through the TGFβ signaling pathway (Fig. 6C).

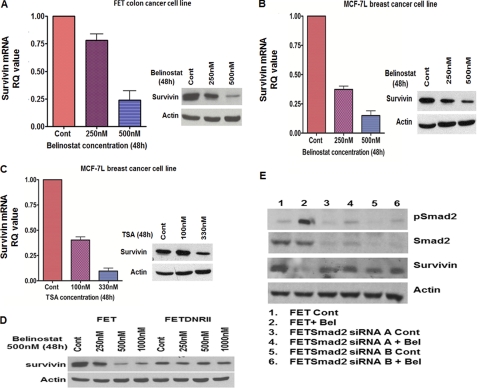

Novel Role of PKA in Belinostat Treatment-mediated Cellular Effects

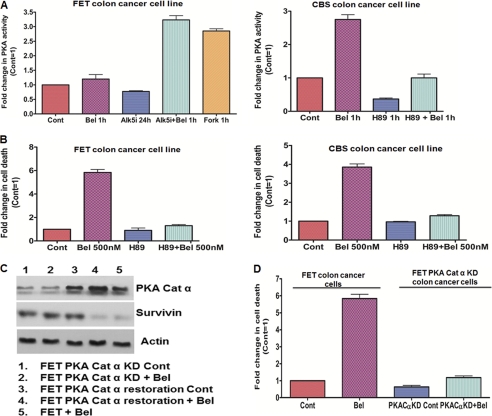

Previously, Zhang et al. (10) made the novel observation that TGFβ activated PKA in Mv1Lu cells. It was shown that PKA was able to regulate the TGFβ-mediated p21WAF1/CIP1 induction and growth inhibition. Furthermore, Dohi et al. (51) showed that PKA activation leads to phosphorylation of survivin on Ser20 leading to its degradation. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that belinostat activates PKA downstream of TGFβ-Smad activation leading to survivin down-regulation and apoptotic cell death. To this end, FET cells were treated with belinostat for 1 h and tested for PKA activation. We observed no change in PKA activity (data not shown). However, it was possible that as FET cells retain functional TGFβ signaling the high basal PKA activity due to autocrine TGFβ activity in the cells might make it difficult to observe any activation effects. To test whether belinostat treatment is able to increase the PKA activity in these cells, they were pretreated with ALK5i for 24 h to inhibit the autocrine TGFβ signaling. Following the removal of medium containing the ALK5i, belinostat was added to the cells with fresh serum-free medium. As shown in Fig. 7A (left panel), belinostat treatment was able to robustly activate PKA in the FET cells through reactivation of TGFβ-Smad signaling. The cAMP analog forskolin was used as a positive control to elevate PKA activity in the cells. We used PKA inhibitor H89 (15 μm) and found that the PKA activity following belinostat treatment was completely abrogated in FET cells (data not shown). The TGFβRII-deficient CBS colon cancer cells showed a robust belinostat-mediated PKA activation within 1 h (Fig. 7A, right panel) that was blocked by H89 treatment. A similar response was observed in TGFβRI-deficient GEO colon cancer cells following belinostat treatment (supplemental Fig. S4A). We determined the role of PKA in belinostat treatment-mediated cell death in the colon cancer cell lines. Low dose H89 (1 μm) pretreatment for 1 h followed by belinostat treatment in the same medium for 48 h significantly reduced the belinostat-mediated cell death in FET, CBS, and GEO cells (Fig. 7B, left and right panels, and supplemental Fig. S4B). We also performed Annexin V staining (supplemental Fig. S4D) and observed an abrogation of apoptosis with H89 pretreatment prior to belinostat treatment. To test the dependence on PKA in this response, we performed stable knockdown of PKA catalytic α subunit using shRNA (designated FETPKACatα KD cells). We observed that belinostat treatment-mediated cell death was significantly reduced in FETPKACatα KD cells indicating that PKA activation is at least partially required for belinostat-mediated cell death (Fig. 7D). As belinostat mediates down-regulation of survivin, we hypothesized that belinostat partially acts through PKA in controlling survivin expression. Indeed, pretreatment of FET cells with H89 partially abrogated the belinostat-mediated survivin loss at 48 h (supplemental Fig. S4C). Similar results were obtained using FETPKACatα KD cells as belinostat treatment was unable to cause survivin down-regulation in these cells at 48 h (Fig. 7C). We further performed a PKA restoration experiment in these knockdown cells to test whether restoration of PKA catalytic α subunit in these FETPKACatα knockdown cell lines leads to belinostat-mediated survivin down-regulation. As shown in Fig. 7C, treatment with belinostat down-regulated survivin in the FETPKACatα cells in which the PKA catalytic α has been restored. Taken together, these data suggest that belinostat-mediated control of aberrant cell survival by restoration of TGFβ signaling partially converges on the TGFβ/PKA signaling and thereby leads to IAP regulation and apoptotic cell death.

FIGURE 7.

Role of PKA in belinostat treatment-mediated cellular effects. Belinostat activated PKA in FET and CBS colon cancer cells dependent on TGFβ signaling (A, left and right panels). Forskolin (10 μm) was used as a positive control. PKA inhibitor H89 (10 μm) was used as a negative control in these experiments. A DNA fragmentation assay was performed after belinostat (500 nm) treatment of FET and CBS cells for 48 h. Pretreatment with a low concentration of PKA inhibitor H89 (1 μm) 1 h prior to belinostat treatment for 48 h abrogated belinostat-mediated cell death (B, left and right panels). Survivin loss by belinostat (500 nm) at 48 h was abrogated in FETPKACatα KD cells. Restoration of the PKA catalytic α subunit in these knockdown cells caused belinostat-mediated survivin down-regulation (C). Belinostat-mediated cell death was dependent on functional TGFβ/PKA signaling. Belinostat (500 nm) treatment of FETPKACatα KD cells for 48 h was unable to induce cell death as measured by DNA fragmentation assay (D). The DNA fragmentation assay results are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Error bars indicate S.E. Actin was used as a loading control for Western blots. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cont, control; Bel, belinostat.

DISCUSSION

It has been shown that epigenetic silencing of the TGFβ receptors plays a major role in suppressing TGFβ tumor suppressor activity in many tumor types including colon, breast, and pancreatic cancer (12, 13). Furthermore, the clinical data are consistent with the prevalence of transcriptional repression as opposed to mutational inactivation as a common mechanism by which TGFβ receptor expression is lost (20, 52–54). Loss of TGFβ receptor expression is associated with poor prognosis in these patients. We have observed that treatment with HDACi leads to restoration of TGFβRI expression as well as increased transcriptional activity of the epigenetically silenced TGFβRII promoter in breast and colon cancer cell lines (16, 23). Given the importance of the tumor suppressor effects of the TGFβ signaling pathway, we studied whether the restoration of TGFβRII expression and therefore TGFβ responsiveness played a role in the antitumor effects of the HDACi belinostat. Additionally, we focused on the mechanisms underpinning the TGFβ-mediated effects of the HDACi belinostat.

Based on our finding that TGFβ signaling represents a survivin repression mechanism (24), we examined whether the belinostat-induced apoptosis and survivin down-regulation were downstream of the restoration of TGFβ signaling. We demonstrated that both belinostat-induced apoptosis and survivin inhibition are TGFβ-dependent events. Survivin is a short lived, bifunctional nodal protein involved in mitosis, and it exerts antiapoptotic effects. Survivin expression in patient tumors is associated with metastasis and poor prognosis (for a review, see Ref. 46).

In this study, we demonstrated that belinostat treatment of cancer cells in vitro leads to TGFβ-dependent survivin transcript and protein down-regulation through dual mechanisms. The late repression of survivin by belinostat is a transcriptional event. This transcriptional repression of the survivin promoter may be related to cell cycle arrest as survivin is regulated by the cell cycle. Belinostat treatment did induce p21WAF1/CIP1, and induction of this CDKI was required for SAHA-mediated degradation of survivin in colon cancer cells (55). However, Danielpour and co-workers (56) reported that TGFβ-mediated repression of survivin transcription requires Smad interaction with the promoter.

In contrast to the transcription-based late inhibition, the early belinostat-mediated down-regulation of survivin appears to involve decreased stability of the protein as reflected by the decreased half-life. This survivin protein instability may be related to our novel findings that belinostat treatment results in an immediate TGFβ-dependent PKA activation response. Although classical PKA activation is cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent, Zhang et al. (10) made the observation that TGFβ signaling activates PKA in a cAMP-independent, Smad 3-dependent manner that in turn leads to growth inhibition. We now report that the HDACi belinostat induced this PKA activation, and it was required for belinostat-mediated survivin degradation. Use of the PKA inhibitor H89 or stable transfection of shRNA to the PKA catalytic subunit abolished this effect. Dohi et al. (51) reported that survivin contributes to cell survival in response to stress in association with another IAP family member, XIAP. Interestingly, PKA activation was shown to induce phosphorylation of survivin on cytosolic Ser20 that in turn dissociated the survivin-XIAP complex leading to stress-induced loss of cell survival signaling. This raised the possibility that the belinostat-mediated TGFβ-dependent effects on survivin half-life might involve disruption of the survivin-XIAP complex by PKA phosphorylation of survivin, which would then be targeted for degradation. The other component of this early belinostat-mediated degradation of survivin is the novel finding that belinostat mediates an early activation of the chymotrypsin activity of the proteasome. Previous studies have reported that SAHA treatment leads to decreased proteasome activity at 24–48 h post-treatment (30), and this has led to clinical trials of HDACis in combination with proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib (30). In the current study, the belinostat-mediated down-regulation of survivin protein at early time points was shown to be mediated through the proteasome. These data predict that belinostat might be able to regulate the ubiquitination of survivin by an as yet unknown mechanism We have evidence that belinostat treatment induces substantial levels of ubiquitination of a broad number of substrates within the cell at these times (supplemental Fig. S5A). PKA has been shown to be involved in the proteasomal degradation of survivin. It has been shown that activation of PKA leads to phosphorylation of survivin Ser20 leading to its dissociation from XIAP and subsequent proteasomal degradation of this caspase inhibitor. However, whether this Ser20 phosphorylation specifically leads to increased ubiquitination of survivin at a yet undetermined site has not yet been determined. Significantly, PKA has been reported as a major regulator of proteasome activity and co-purifies with the proteasome (57, 58). Furthermore, PKA activation has been shown to enhance the chymotrypsin activity of the proteasome (59) and increase the transport function of the Rpt6 subunit of the 19 S outer ring (60). Although the strategic use of proteasomal inhibitors in combination with HDACis as potential anticancer drugs is in a nascent stage, we made the novel observation that belinostat at early time points significantly increased the chymotrypsin proteasomal activity. This may have implications for the timing of the administration of HDACis in combination with proteasome inhibitors in the clinic.

The HDACis are in clinical trials but have met with limited success in the treatment of solid tumors. The overexpression of class I HDACs in many patient tumor types and their association with poor prognosis point to HDAC inhibition as a potentially useful clinical target. Interestingly, despite the potential for genome wide effects of HDAC inhibitors, studies have shown that up to 22% of genes responded to HDAC inhibitor treatment (61). However, the first generation HDAC inhibitors affect most classes of HDACs with the exception of the sirtuins. Specific inhibition of HDAC enzymes may lead to increased efficacy of this epigenetic drug, and the development of class/isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors is underway. However, another way to increase treatment success may be to identify specific patient populations that might benefit from these drugs. The findings from this report point toward a novel use of the HDAC inhibitor belinostat in the therapeutic context. We identified restoration of TGFβRII with concomitant activation of TGFβ signaling as a major contributor to the cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis mediated by belinostat treatment of cancer cells in vitro. The restoration of TGFβ signaling by belinostat led to the down-regulation of survivin via dual mechanisms. The stability of the survivin protein was decreased at early times after belinostat treatment, whereas transcriptional repression occurred at later times, results that reinforce the TGFβ-dependent inhibition of survivin. Therefore, patient populations exhibiting high survivin expression with epigenetically silenced TGFβRII might potentially benefit from the use of this HDAC inhibitor.

In conclusion, we report that belinostat-mediated activation of PKA led to survivin down-regulation and increased cell death. Using PKA inhibitor H89 or shRNA knockdown of PKA catalytic subunit, we were able to show the dependence of belinostat on TGFβ/PKA function in mediating control of aberrant cell survival and inducing cell death. Furthermore, the apoptotic activities of belinostat were attenuated in cells devoid of functional TGFβRII or its downstream mediators Smad2 and PKA. This is an important linkage in the mechanism of action of HDACis identified for the first time in this work. HDACi-induced cell death has been linked to death receptor up-regulation, blockade of angiogenesis, and cell cycle arrest (62). Although our observations do not exclude other mechanisms and pathways contributing to HDACi-induced cell death, they do strongly implicate TGFβ/PKA signaling as components of a pathway that is involved in the belinostat treatment-mediated control of aberrant cell survival converging on survivin function as a consequence of restoration of TGFβRII tumor suppressor signaling.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA72001 and CA38173 (to M. G. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- HDACi

- histone deacetylase inhibitor

- TGFβRI

- TGFβ receptor type I, TGFβRII, transforming growth factor β receptor II

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- SAHA

- suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- Catα

- catalytic α

- KD

- knockdown

- CDKI

- cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor

- ALK5i

- ALK5 inhibitor I

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- IAP

- inhibitor of apoptosis

- XIAP

- X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis

- CHX

- cycloheximide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Markowitz S. D., Bertagnolli M. M. (2009) N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2449–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grady W. M. (2005) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 684–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ropero S., Esteller M. (2007) Mol. Oncol. 1, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lehmann A., Denkert C., Budczies J., Buckendahl A. C., Darb-Esfahani S., Noske A., Müller B. M., Bahra M., Neuhaus P., Dietel M., Kristiansen G., Weichert W. (2009) BMC Cancer 9, 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones P. A., Baylin S. B. (2002) Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Timmermann S., Lehrmann H., Polesskaya A., Harel-Bellan A. (2001) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 728–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolden J. E., Peart M. J., Johnstone R. W. (2006) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 769–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marks P. A., Jiang X. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, 549–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richon V. M., Sandhoff T. W., Rifkind R. A., Marks P. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10014–10019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang L., Duan C. J., Binkley C., Li G., Uhler M. D., Logsdon C. D., Simeone D. M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2169–2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ammanamanchi S., Brattain M. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3348–3352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Periyasamy S., Ammanamanchi S., Tillekeratne M. P., Brattain M. G. (2000) Oncogene 19, 4660–4667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Venkatasubbarao K., Ammanamanchi S., Brattain M. G., Mimari D., Freeman J. W. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 6239–6247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ammanamanchi S., Kim S. J., Sun L. Z., Brattain M. G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16527–16534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ammanamanchi S., Brattain M. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32854–32859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ammanamanchi S., Brattain M. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32620–32625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ammanamanchi S., Freeman J. W., Brattain M. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35775–35780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li F., Ling X., Huang H., Brattain L., Apontes P., Wu J., Binderup L., Brattain M. G. (2005) Oncogene 24, 1385–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kang S. H., Bang Y. J., Im Y. H., Yang H. K., Lee D. A., Lee H. Y., Lee H. S., Kim N. K., Kim S. J. (1999) Oncogene 18, 7280–7286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsushita M., Matsuzaki K., Date M., Watanabe T., Shibano K., Nakagawa T., Yanagitani S., Amoh Y., Takemoto H., Ogata N., Yamamoto C., Kubota Y., Seki T., Inokuchi H., Nishizawa M., Takada H., Sawamura T., Okamura A., Inoue K. (1999) Br. J. Cancer 80, 194–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Osada H., Tatematsu Y., Masuda A., Saito T., Sugiyama M., Yanagisawa K., Takahashi T. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 8331–8339 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park S. H., Lee S. R., Kim B. C., Cho E. A., Patel S. P., Kang H. B., Sausville E. A., Nakanishi O., Trepel J. B., Lee B. I., Kim S. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5168–5174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang W., Zhao S., Ammanamanchi S., Brattain M., Venkatasubbarao K., Freeman J. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10047–10054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang J., Yang L., Yang J., Kuropatwinski K., Wang W., Liu X. Q., Hauser J., Brattain M. G. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 3152–3160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Monks A., Hose C. D., Pezzoli P., Kondapaka S., Vansant G., Petersen K. D., Sehested M., Monforte J., Shoemaker R. H. (2009) Anticancer Drugs 20, 682–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ye S. C., Foster J. M., Li W., Liang J., Zborowska E., Venkateswarlu S., Gong J., Brattain M. G., Willson J. K. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 4725–4731 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun L., Wu G., Willson J. K., Zborowska E., Yang J., Rajkarunanayake I., Wang J., Gentry L. E., Wang X. F., Brattain M. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26449–26455 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou Y., Brattain M. G. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 5848–5856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maeda M., Johnson K. R., Wheelock M. J. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 873–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heider U., von Metzler I., Kaiser M., Rosche M., Sterz J., Rötzer S., Rademacher J., Jakob C., Fleissner C., Kuckelkorn U., Kloetzel P. M., Sezer O. (2008) Eur. J. Haematol. 80, 133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taghiyev A. F., Guseva N. V., Glover R. A., Rokhlin O. W., Cohen M. B. (2006) Cancer Biol. Ther. 5, 1199–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamamoto S., Tanaka K., Sakimura R., Okada T., Nakamura T., Li Y., Takasaki M., Nakabeppu Y., Iwamoto Y. (2008) Anticancer Res. 28, 1585–1591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Derynck R., Zhang Y. E. (2003) Nature 425, 577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fandy T. E., Shankar S., Ross D. D., Sausville E., Srivastava R. K. (2005) Neoplasia 7, 646–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hitomi T., Matsuzaki Y., Yokota T., Takaoka Y., Sakai T. (2003) FEBS Lett. 554, 347–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang J., Han W., Zborowska E., Liang J., Wang X., Willson J. K., Sun L., Brattain M. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17366–17371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang J., Sergina N., Ko T. C., Gong J., Brattain M. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40237–40244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moustakas A., Kardassis D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6733–6738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiang S., Dowdy S. C., Meng X. W., Wang Z., Jones M. B., Podratz K. C., Jiang S. W. (2007) Gynecol. Oncol. 105, 493–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Okabe S., Tauchi T., Nakajima A., Sashida G., Gotoh A., Broxmeyer H. E., Ohyashiki J. H., Ohyashiki K. (2007) Stem Cells Dev. 16, 503–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dowdy S. C., Jiang S., Zhou X. C., Hou X., Jin F., Podratz K. C., Jiang S. W. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 2767–2776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heeres J. T., Hergenrother P. J. (2007) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11, 644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Altieri D. C. (2010) Biochem. J. 430, 199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marks P. A. (2007) Oncogene 26, 1351–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Altieri D. C. (2008) Oncogene 27, 6276–6284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Altieri D. C. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mehrotra S., Languino L. R., Raskett C. M., Mercurio A. M., Dohi T., Altieri D. C. (2010) Cancer Cell 17, 53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chiou S. K., Mandayam S. (2007) Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 1485–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao J., Tenev T., Martins L. M., Downward J., Lemoine N. R. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 4363–4371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kleeff J., Kornmann M., Sawhney H., Korc M. (2000) Int. J. Cancer 86, 399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dohi T., Xia F., Altieri D. C. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 17–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Borczuk A. C., Kim H. K., Yegen H. A., Friedman R. A., Powell C. A. (2005) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172, 729–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim I. Y., Ahn H. J., Zelner D. J., Shaw J. W., Lang S., Kato M., Oefelein M. G., Miyazono K., Nemeth J. A., Kozlowski J. M., Lee C. (1996) Clin. Cancer Res. 2, 1255–1261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gobbi H., Arteaga C. L., Jensen R. A., Simpson J. F., Dupont W. D., Olson S. J., Schuyler P. A., Plummer W. D., Jr., Page D. L. (2000) Histopathology 36, 168–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nawrocki S. T., Carew J. S., Douglas L., Cleveland J. L., Humphreys R., Houghton J. A. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 6987–6994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang J., Song K., Krebs T. L., Jackson M. W., Danielpour D. (2008) Oncogene 27, 5326–5338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pereira M. E., Wilk S. (1990) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 283, 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zong C., Gomes A. V., Drews O., Li X., Young G. W., Berhane B., Qiao X., French S. W., Bardag-Gorce F., Ping P. (2006) Circ. Res. 99, 372–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang F., Hu Y., Huang P., Toleman C. A., Paterson A. J., Kudlow J. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22460–22471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang F., Paterson A. J., Huang P., Wang K., Kudlow J. E. (2007) Physiology 22, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Peart M. J., Smyth G. K., van Laar R. K., Bowtell D. D., Richon V. M., Marks P. A., Holloway A. J., Johnstone R. W. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3697–3702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fotheringham S., Epping M. T., Stimson L., Khan O., Wood V., Pezzella F., Bernards R., La Thangue N. B. (2009) Cancer Cell 15, 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Arnold N. B., Arkus N., Gunn J., Korc M. (2007) Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.