Abstract

Metabolic engineering of photosynthetic organisms is required for utilization of light energy and for reducing carbon emissions.Control of transcriptional regulators is a powerful approach for changing cellular dynamics, because a set of genes is concomitantly regulated. Here, we show that overexpression of a group 2 σ factor, SigE, enhances the expressions of sugar catabolic genes in the unicellular cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Transcriptome analysis revealed that genes for the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway and glycogen catabolism are induced by overproduction of SigE. Immunoblotting showed that protein levels of sugar catabolic enzymes, such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, glycogen phosphorylase, and isoamylase, are increased. Glycogen levels are reduced in the SigE-overexpressing strain grown under light. Metabolome analysis revealed that metabolite levels of the TCA cycle and acetyl-CoA are significantly altered by SigE overexpression. The SigE-overexpressing strain also exhibited defective growth under mixotrophic or dark conditions. Thus, SigE overexpression changes sugar catabolism at the transcript to phenotype levels, suggesting a σ factor-based engineering method for modifying carbon metabolism in photosynthetic bacteria.

Keywords: Bacterial Metabolism, Bacterial Transcription, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Glycogen, Transcription Regulation, Cyanobacteria

Introduction

Carbon metabolism in photosynthetic organisms has received considerable attention because increasing carbon emission is thought to be the cause of global warming. Primary production is governed not only by land plants but also by ocean-dwelling phytoplanktons, including cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria are widely distributed in diverse ecological niches, and the unicellular cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis 6803) is one of the most widely used species for the study of photosynthetic bacteria. The genome of Synechocystis 6803 was first determined in 1996 (1), and transcriptome and proteome analyses have been performed. Several genes have been identified whose mutations alter the metabolite levels of primary carbon metabolism (2–4).

The engineering of carbon metabolism leads to modified production of various metabolites; however, the robust control of primary metabolism often obstructs such modification. For example, overexpression of the genes of eight enzymes in yeast cells did not increase ethanol formation or key metabolite levels (5). Several researchers have modified genes encoding transcriptional regulators instead of metabolic enzymes. Yanagisawa et al. (6) generated transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants expressing increased levels of the Dof1 transcription factor, which is an activator of gene expression associated with organic acid metabolism, including phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase. Overexpression of Dof1 resulted in increased enzymatic activities of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and pyruvate kinase, increased metabolite levels, such as amino acids (asparagine, glutamine, and glutamate), and better growth under low nitrogen conditions (6). These results indicate that modification of transcriptional regulator(s) is practical for metabolic engineering.

Primary carbon metabolism is divided into anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and gluconeogenesis, and catabolic reactions, such as glycolysis and the oxidative pentose phosphate (OPP)2 pathway (7). Glycogen, the carbon sink of most cyanobacteria, provides carbon sources and reducing power under heterotrophic conditions. Glycogen degradation is catalyzed by glycogen catabolic enzymes, such as glycogen phosphorylase (encoded by glgP) and isoamylase (encoded by glgX). The genome of Synechocystis 6803 contains two glgP (sll1356 and slr1367) and two glgX (slr0237 and slr1857) genes (8). A metabolomic study showed that glucose produced from glycogen is degraded mainly through the OPP pathway under heterotrophic conditions (9). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Glc-6-PD, encoded by zwf) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGD, encoded by gnd) are key enzymes of the OPP pathway, producing NADPH and pentose phosphate for nucleotide biosynthesis. Cyanobacterial Glc-6-PD is up-regulated by OpcA through protein-protein interaction, and opcA is essential for NADPH production during nighttime (10, 11). The transcript levels of genes of the OPP pathway are altered by light-dark transition, circadian cycle, or nitrogen status (12–14). Thus, sugar catabolic enzymes, including Glc-6-PD and 6PGD, are regulated at both the transcriptional and post-translational levels in cyanobacteria.

σ factors, subunits of the bacterial RNA polymerase, are divided into four groups, and cyanobacteria are characterized by possessing multiple group 2 σ factors, whose promoter recognition is similar to group 1 σ factor (15, 16). Transcriptome analysis revealed that the disruption of sigE, one of four group 2 σ factors in Synechocystis, results in decreased transcript levels of three glycolytic genes (pfkA, encoding phosphofructokinase; gap1, encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; and pyk, encoding pyruvate kinase), four OPP pathway genes (zwf, opcA, gnd, and tal (encoding transaldolase)), and two glycogen catabolic genes (glgP (sll1356) and glgX (slr0237)) (12). SigE protein levels and activities are controlled in response to light signals (17). Phenotypic analysis showed that the disruption of sigE results in decreased level of glycogen and reduced viability under dark conditions (12). Thus, transcriptome and phenotypic analyses indicate that SigE is a positive regulator of sugar catabolism, although proteomic and metabolomic analyses have not been performed.

In this study, we generated a SigE-overexpressing strain and measured the transcript, protein, and metabolite levels and the phenotypes associated with sugar catabolism. We revealed that SigE overexpression activates the expressions of sugar catabolic enzymes and modifies the amounts of glycogen, acetyl-CoA, and metabolites of the TCA cycle.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

The glucose-tolerant (GT) strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, isolated by Williams (18), and the SigE-overexpressing strain were grown in BG-110 liquid medium with 5 mm NH4Cl (buffered with 20 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 7.8)), termed modified BG-11 medium. Liquid cultures were bubbled with 1% (v/v) CO2 in air at 30 °C under continuous white light (∼50–70 μmol photons m−2 s−1) (19). For plate cultures, modified BG-110 (the concentration of NH4Cl was 10 mm instead of 5 mm in liquid medium) was solidified using 1.5% (w/v) agar (BD Biosciences) and incubated in air at 30 °C under continuous white light (∼ 50–70 μmol photons m−2 s−1). The null mutant of sigE, named G50, was generated as published previously (12). For the SigE-overexpressing strain and the sigE null mutant, 20 μg/ml kanamycin (Sigma) was supplemented in the modified BG-11 liquid medium. Dark conditions were achieved by wrapping culture plates with aluminum foil. Growth and cell densities were measured at A730 with a Beckman DU640 spectrophotometer.

Construction of SigE-overexpressing Strain

The sigE (sll1689) coding region was amplified by PCR using KOD DNA polymerase (Toyobo), the forward primer 5′-ATTATTCATATGAGCGATATGTCTTCC-3′, and the reverse primer 5′-CCGATATCCTATAACCAACCTTTGAG-3′. The resulting 1.1-kb amplified fragment was digested with NdeI and EcoRV (Takara Bio) and inserted into an NdeI- and HpaI-digested vector constructed by Satoh et al. (20), named pTKP2031V. The sigE gene with the psbAII promoter (spanning −297 to +3 from the initiation codon of psbAII) was introduced into the genomic region between slr2030 and slr2031 together with a kanamycin resistance cassette, because slr2031 was not functional in this strain. Transformation was performed as described previously (12). Briefly, cells of mid-exponential phase cultures of Synechocystis 6803 were suspended in 100–200 μl of BG-11 liquid medium, and 1 μl of plasmid solution (about 250 μg/ml) was mixed in a test tube. The culture was then spread onto a mixed nitrocellulose membrane filter placed on a BG-11 plate. After cultivation at 30 °C under continuous white light for 1 day, the membrane filter was transferred onto a BG-11 plate with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The resultant colonies were replated three times, and the transformation was confirmed by Northern blotting and immunoblotting.

RNA Isolation and Microarray Analysis

Cells of mid-exponential phase cultures of Synechocystis 6803 (A730, 0.5–0.7) grown in modified BG-11 were collected by centrifugation at 9,800 × g for 3 min. RNA was isolated from the cells by the previously described acid phenol/chloroform method (21). Microarray analysis was performed as described previously (12). Signals were quantified using ImaGene software version 4.0 (BioDiscovery).

RT-PCR

RNA was isolated as for the microarray analysis. cDNA was produced with Superscript First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen) with 4 μg of total RNAs. Absence of genomic DNA was checked using samples without reverse transcriptase. The cDNAs were then amplified with GoTaq (Promega) in a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, iCycler). Thermal cycling was programmed as 95 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min for 25–28 cycles, followed by holding at 4 °C. Gene-specific primers used for cDNA amplification are as follows; fbaII forward, 5′-ATGGGATCCCCATGGCTCTTGTACCAATG-3′, and fbaII reverse, 5′-TGAGTCGACCTACACAGCAACGGAGGT-3′; apqZ forward, 5′-ATGAAAAAGTACATTGCTG-3′, and apqZ reverse, 5′-TCACTCTGCTTCGGGTTC-3′; sll0783 forward, 5′-ATGCCAGAGGTAACTAAG-3′, and sll0783 reverse, 5′-TTACATTGTCCAAGTATC-3′; nrtB forward, 5′-ATGGCTAGTTCCACCGCT-3′, and nrtB reverse, 5′-TCACTTTTGCTCCGCTGG-3′; recA forward, 5′-CTTGACCCCGTTTATTCC-3′, and recA reverse, 5′-AGCGGCGATTTCAGGATT-3′.

Northern Blot Analysis

RNA was isolated as for microarray analysis. Northern blot analysis was performed with digoxigenin (DIG) probes according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Applied Science). RNAs were electrophoresed through an agarose gel containing 3% formaldehyde. The RNAs were blotted onto Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare) by capillary blotting with 10× SSC (1.5 m NaCl, 150 mm sodium citrate) and incubated with Hybridization buffer (5× SSC, 50% formamide, 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 2% Blocking Reagent (Roche Applied Science), 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 7% sodium lauryl sulfate, and 50 μg/ml yeast total RNA) for 1 h at 48 °C. One microliter of gene-specific DIG-labeled probe generated as in Ref. 12 was then mixed with a membrane in Hybridization buffer and incubated at 48 °C overnight. The membrane was washed with Wash buffer 1 (2× SSC, 0.1% SDS) for 10 min at room temperature and Wash buffer 2 (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS) for 30 min at 68 °C, followed by washing with Wash buffer 3 (0.1 m maleic acid, 0.15 m NaCl (pH 7.5), and 0.3% Tween 20) for 5 min at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with Blocking buffer (0.1 m maleic acid, 0.15 m NaCl (pH 7.5), and 1% Blocking Reagent) for 1 h at room temperature. Antibodies for DIG (anti-DIG-AP, Fab fragments, Roche Applied Science) were added at a dilution of 1:10,000 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed with Wash buffer 3 for 30 min and equilibrated by Equilibration buffer (0.1 m Tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 0.1 m NaCl, 50 mm MgCl2) for 10 min at room temperature. After adding CDP-Star, Ready-to-Use (Roche Applied Science), and incubating for 15 min under dark conditions, chemiluminescence was detected by a photon counter (Hamamatsu Photonics, ARGUS-20, version 2.0).

Production of Antisera and Immunoblotting

Antisera against Glc-6-PD, 6PGD, GlgX (Slr1793 and Slr0237), GlgP (Slr1367 and Sll1356), Gap2 (one of two glycolaldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases), and FbaII (one of two fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase) were commercially produced by Tampaku Seisei Kogyo Co. Ltd. Peptides of sequence GGKPVPGYREEPGVDPSSTT for Glc-6-PD, SSSLDYFDSYRRAVLPQN for 6PGD, NFALPRFPDENDGSE for GlgX (Slr0237), GTQPNWDDIYQHRGRLS for GlgX (Slr1857), EIIHNEKNQPK for GlgP (Slr1367), EPYTDDQGNYR for GlgP (Sll1356), SDRNPLNLPWAEWN for Gap2, and CHGAYKFTRKPTGEVL for FbaII were synthesized and injected into rabbits. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (15).

Measuring Glycogen Levels

Cells (∼6 × 108) were suspended in 100 μl of 3.5% (v/v) sulfuric acid and boiled for 40 min. After centrifugation for 1 min, the supernatant was mixed with 350 μl of 10% TCA solution (as a blank control, 100 μl water was used), followed by placing for 5 min at room temperature. After centrifugation for 5 min, 150 μl of supernatant and 750 μl of 6% o-toluidine reagent (diluted by acetic acid) were mixed and briefly vortexed. After boiling the mixture for 10 min and cooling with water (room temperature) for 3 min, the amount of glycogen was monitored by the absorbance at 635 nm.

Analysis of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD Activities

Glc-6-PD and 6PGD activities were measured by monitoring the glucose-6-phosphate- or 6-phosphogluconate-dependent increase in NADPH concentration at A340 with a Beckman DU640 spectrophotometer. For assaying Glc-6-PD activity, cells were suspended in 1 ml of buffer A (55 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 3.4 mm MgCl2) and disrupted by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant, containing 90 μg of proteins, was used for the enzyme assay. The reaction was initiated at 25 °C in a mixture containing 45 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2.8 mm MgCl2, 1 mm NADP+, and 10 mm glucose 6-phosphate, and the change in A340 was monitored for 1 min. As a control, the change in A340 in the absence of glucose 6-phosphate was measured and subtracted from the experimental values. For assaying 6PGD activity, cells were suspended in 1 ml of 100 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5) and disrupted by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant, containing 40 μg of proteins, was used for the enzyme assay. The reaction was initiated at 25 °C in a mixture containing 100 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5), 1 mm NADP+, and 10 mm 6-phosphogluconate, and the change in A340 was monitored for 1 min. As a control, the change in A340 in the absence of 6-phosphogluconate was measured and subtracted from the experimental values. One unit of Glc-6-PD or 6PGD activity was defined as the formation of 1 μmol of NADPH per min under the experimental conditions.

Capillary Electrophoresis/Mass Spectrometry (CE/MS) Analysis

Cells of mid-exponential phase cultures of Synechocystis 6803 (A730, 0.5–0.7) grown in modified BG-11 were collected by centrifugation at 9,800 × g for 3 min, followed by freezing in liquid nitrogen. 50–200 mg of cells (fresh weight) were suspended in 600 μl of 60% (v/v) methanol, including 27 μm 10-camphorsulfonic acid as an internal standard, and vortexed by a MicroSmash (Tomy) eight times for 1 min at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 20,400 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. 400 μl of the supernatant was then centrifuged through a Millipore 5-kDa cutoff filter at 10,000 × g for 90 min. 300 μl of the filtrate was dried for 120 min by a centrifugal concentrator. The residue was dissolved in 20 μl of water and used for CE/MS analysis. The CE/MS system and conditions were as described previously (22).

RESULTS

Overexpression of SigE Induces Sugar Catabolic Genes and Genes Related to Energy Metabolism and Signal Transduction

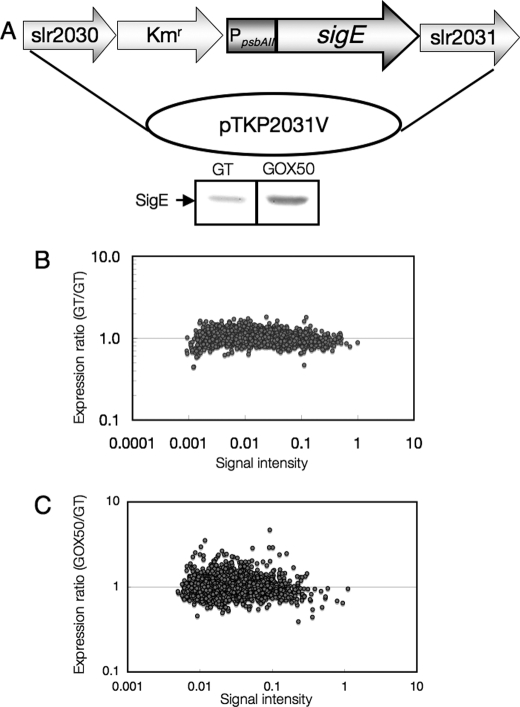

To increase the expression of SigE, the promoter of psbAII, whose full-length gene encodes Photosystem II D1 protein, was fused with the coding region of sigE (Fig. 1A). Immunoblotting showed increased levels of SigE proteins in the recombinant strain, which was named GOX50 (Fig. 1A). We then compared the transcript profiles of the parental glucose-tolerant (GT) strain of Synechocystis 6803 and GOX50 grown under light. First, we performed an internal control experiment in which Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNAs were synthesized from total RNA of GT cells (Fig. 1B). All spots, for which the signals from Cy3-labeled cDNA were divided by signals from Cy5-labeled cDNA, corresponded to expression levels of 1.8 and 0.5 (supplemental Table S1). Total RNA was then extracted from GT and GOX50 cells and used for a microarray experiment with a gene chip, CyanoChip version 1.6 (Takara Bio), containing fragments of 3076 Synechocystis ORFs (Fig. 1C). The top 20 genes whose expression increased in response to SigE overexpression are listed in Table 1. Genes that were previously shown to be SigE regulons, such as tal, gnd, cph1 (encoding cyanobacterial phytochrome 1), glgP (sll1356), and glgX (slr0237) were induced by more than 1.8-fold by SigE overexpression (Table 1 and supplemental Table S2). In addition to sugar catabolic genes, the expression levels of genes encoding bidirectional hydrogenases (sll1220–sll1226), NAD(P) transhydrogenase (pntA;slr1239 and pntB;slr1434), and poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthases (slr1829 and slr1830) were increased in GOX50 (Table 1 and supplemental Table S2). To confirm the microarray analysis, Northern blotting with cph1, pntA, and gnd probes was performed. The result demonstrated that the mRNA levels of the three genes were increased by SigE overexpression (supplemental Fig. S1A). The transcript levels of genes down-regulated by SigE overexpression (fbaII, apqZ, sll0783, and nrtB) were also measured by RT-PCR and were consistent with the microarray analysis (supplemental Fig. S1B).

FIGURE 1.

A, SigE overexpression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. A 1.1-kb fragment of the sigE coding region was ligated with the promoter of psbAII. A kanamycin resistance cassette is located upstream of the psbAII promoter and flanked by slr2030 and slr2031. The lower panel shows the protein levels of SigE in the GT and GOX50 strains. A total of 5 μg of protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and SigE proteins were detected by SigE antiserum (12). B, internal control experiment for the microarray analysis using RNAs from GT cells. Total RNAs isolated from biologically independent GT cells were labeled with either Cy3 or Cy5. Each point represents the GT/GT expression ratio, and the signal intensity of the Cy3-labeled cDNAs for an ORF fragment on the array is shown. C, microarray analysis of gene expression, comparing transcript profiles of the GT and GOX50 cells. Each point represents the GOX50/GT expression ratio, and the signal intensity in the GT strain for an ORF fragment on the array is shown. Experiments were performed three times with biologically independent RNAs. The data from the means of three experiments are shown.

TABLE 1.

Top 20 genes whose expression levels increased by SigE overexpression

Data represent the ratio of transcript level in GOX50 to that in GT. The array included at least two spots for each ORF. Values represent means ± S.D. of data from six spots.

| Gene | ORF No. | Gene function | Ratio (GOX50/GT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sigE | sll1689 | Group 2 σ factor SigE | 4.70 ± 1.15a |

| slr0869 | Hypothetical protein | 3.53 ± 1.22a | |

| slr0870 | Hypothetical protein | 2.98 ± 1.59b | |

| tal | slr1793 | Transaldolase | 2.92 ± 0.13a |

| gnd | sll0329 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 2.91 ± 0.20a |

| slr1240 | Hypothetical protein | 2.86 ± 0.59b | |

| hoxE | sll1220 | Putative diaphorase subunit of the bidirectional hydrogenase | 2.65 ± 0.95a |

| slr0871 | Hypothetical protein | 2.54 ± 1.41 | |

| pntA | slr1239 | Nucleotide transhydrogenase α subunit | 2.48 ± 0.21a |

| slr1437 | Hypothetical protein | 2.44 ± 0.64a | |

| sll0611 | Hypothetical protein | 2.41 ± 0.91b | |

| sll1222 | Hypothetical protein | 2.40 ± 0.29a | |

| cph1 | slr0473 | Cyanobacterial phytochrome 1 | 2.40 ± 0.83b |

| ssl1533 | Hypothetical protein | 2.39 ± 0.88b | |

| slr1241 | Hypothetical protein | 2.34 ± 0.57a | |

| fus | slll0830 | Elongation factor EF-G | 2.31 ± 1.22 |

| phaE | slr1829 | Putative poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthase component | 2.28 ± 0.24a |

| hoxF | sll1221 | Diaphorase subunit of bidirectional hydrogenase | 2.26 ± 0.39a |

| sll1236 | Hypothetical protein | 2.26 ± 0.93b |

a Student's t test was performed with data from six spots (supplemental Table S4), and the genes with differences in expression between GT and GOX50 that were statistically significant are p < 0.005).

b Genes with differences in expression between GT and GOX50 and statistically significant, p < 0.05.

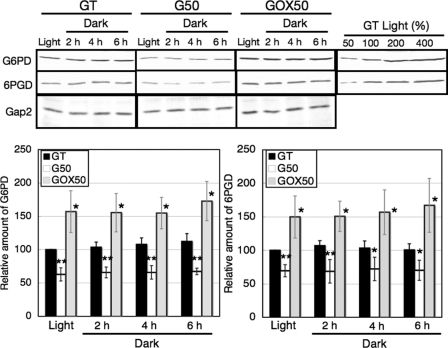

Increased Levels of OPP and Glycogen Catabolic Enzymes and Decreased Glycogen Storage by SigE Overexpression

Northern blotting was then performed with the GT and GOX50 strains grown under light or dark conditions. First, we checked the transcript and protein levels of SigE under light and dark conditions. SigE transcripts and proteins persisted in GOX50 at least 3 days after light-to-dark transition (supplemental Fig. S1, C and D). Northern blotting showed that the transcript levels of four genes of the OPP pathway (zwf, opcA, gnd, and tal) increased by 1.5–4 times in GOX50, compared with the parental GT strain under both light and dark conditions (supplemental Fig. S2). Protein levels of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD were subsequently measured by immunoblotting. A sigE-null mutant, named G50, showed reduced transcript levels of zwf and gnd (12). The protein levels of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD in G50 were decreased under either light or dark conditions (Fig. 2). Conversely, SigE overexpression resulted in 1.5–3-fold increases in Glc-6-PD and 6PGD protein levels (Fig. 2). The protein levels of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD remained relatively constant for 6 h after the transition from light to dark conditions in the GT, G50, and GOX50 strains (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Levels of Glc-6-PD, 6PGD, and Gap2 proteins in the GT, G50, and GOX50 strains under light and dark conditions. Total protein (12 μg for Glc-6-PD (G6PD) and Gap2 or 6 μg for 6PGD) was subjected to immunoblotting. Gap2 protein levels are shown as a control. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from five independent experiments. The levels were calibrated relative to the value obtained in the GT strain under light conditions, which was set at 100%. Differences between GT and G50 or GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005).

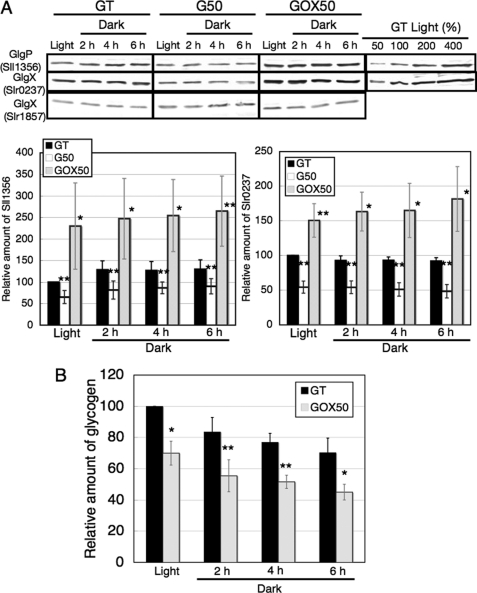

For glycogen catabolic enzymes, we generated antisera against two GlgPs (Sll1356 and Slr1367) and two GlgXs (Slr1857 and Slr0237); however, the antiserum against GlgP (Slr1367) could not detect the protein clearly. The results of immunoblotting showed that the protein levels of GlgP (Sll1356) and GlgX (Slr0237) were decreased by SigE disruption and increased by SigE overexpression, whereas those of GlgX (Slr1857) were unchanged (Fig. 3A). The amount of glycogen in the SigE overexpression strain was about 70% that in GT strain under light conditions (Fig. 3B). The rates of glycogen degradation under dark conditions were similar between the GT and GOX50 strains (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

A, levels of GlgP (Sll1356) and GlgX (Slr0237 and Slr1857) proteins in the GT, G50, and GOX50 strains under light and dark conditions. Total protein (16 μg) was subjected to immunoblotting. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from seven or five independent experiments of immunoblotting with antisera against GlgP (Sll1356) and GlgX (Slr1857), respectively. The levels were calibrated relative to the value obtained in the GT strain under light conditions, which was set at 100%. Differences between GT and G50 or GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005). B, levels of glycogen in the GT and GOX50 strains under light and dark conditions. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from three independent experiments. The levels were calibrated relative to the value obtained in the GT strain under light conditions, which was set at 100%. Differences between GT and GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005).

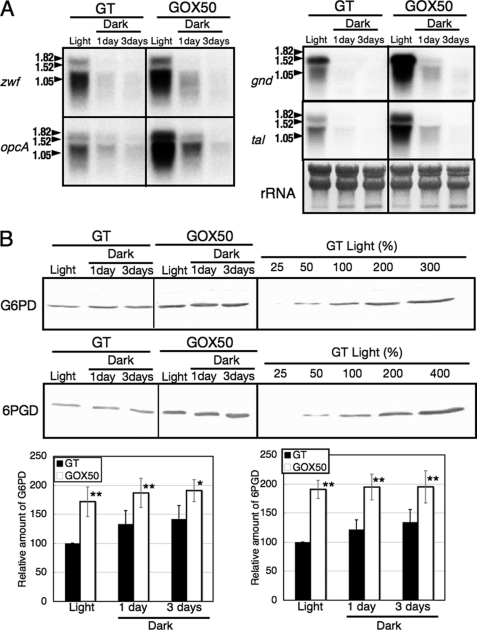

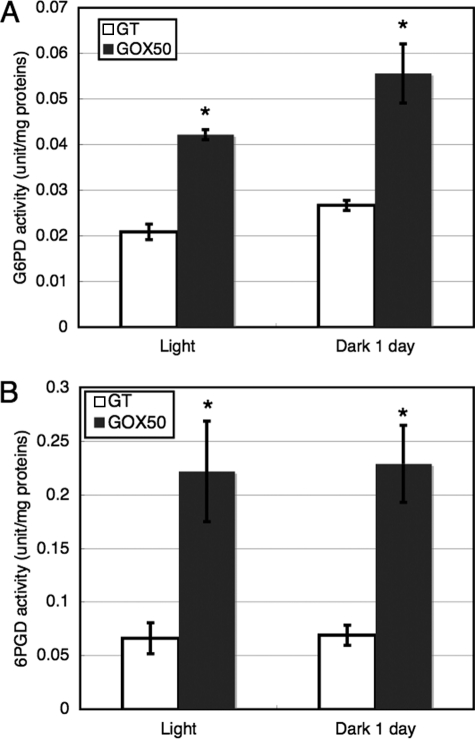

The transcript levels of zwf, opcA, gnd, tal, and protein levels of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD in cells grown under prolonged dark conditions were also measured. The transcripts of four the OPP pathway genes diminished 1 day after light-to-dark conditions in both GT and GOX50 (Fig. 4A). However, the protein levels of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD in both GT and GOX50 were unchanged 3 days after light-to-dark transition (Fig. 4B). The enzyme activities of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD were also measured, and the results showed that both activities were increased by SigE overexpression (Fig. 5). The activities of Glc-6-PD and 6PGD were increased by about two to four times compared with those in GT by SigE overexpression, under both light and dark conditions (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 4.

A, Northern blot analysis of transcripts derived from four genes of the OPP pathway (zwf, opcA, gnd, and tal) under light and dark conditions. The GT and GOX50 strains were grown in modified BG-11 medium, and their RNA was isolated either before or 1 or 3 days after the shift from light to dark. B, levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and 6PGD proteins in the GT and GOX50 strains under light and dark conditions. Proteins were extracted from cells grown under light or dark for 1 or 3 days. Total protein (12 mg for Glc-6-PD or 6 mg for 6PGD) was subjected to immunoblotting. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from five independent experiments. The expression levels were calibrated relative to the value obtained in the GT strain under light conditions, which was set at 100%. Differences between GT and GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005).

FIGURE 5.

Enzyme activities of Glc-6-PD (A) and 6PGD (B) under light and dark conditions. The GT and GOX50 cells grown under light or dark for 1 day were isolated, and the proteins were extracted. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from three independent experiments. Differences between GT and GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05).

In addition to genes induced in GOX50, genes repressed by SigE overexpression were investigated. FbaII, a fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, class II, was the second most down-regulated gene in GOX50 (supplemental Table S2). Antibodies against FbaII were generated, and the protein levels were assessed (supplemental Fig. S3). The results showed that FbaII proteins were decreased by SigE overexpression under light conditions and 1 day after light-to-dark transition (supplemental Fig. S3).

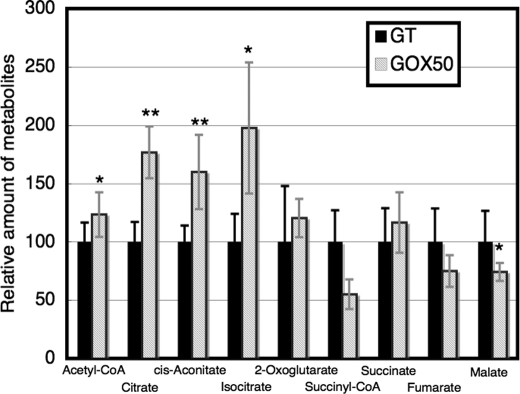

CE/MS Analysis Revealed the Alteration of Metabolite Levels of the TCA Cycle and Acetyl-CoA by SigE Overexpression

Besides the transcript and protein levels of sugar catabolic enzymes, metabolite levels of sugar catabolism were measured. CE/MS analysis detected 67 peaks that were annotated as known metabolites, although several peaks showed large standard deviation values (supplemental Table S3). The metabolome analysis revealed that the levels of metabolites of glycolysis, such as glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate, dihydroxyacetone-phosphate, and phosphoenolpyruvate were similar between the GT and GOX50 strains (supplemental Table S3). In terms of the metabolites of the OPP pathway, the total amounts of ribulose 5-phosphate and ribose 5-phosphate (the analysis could not distinguish the two metabolites) were slightly increased by SigE overexpression, whereas erythrose 4-phosphate did not change (supplemental Table S3). In contrast to metabolites upstream of sugar catabolism, metabolite levels of the TCA cycle and acetyl-CoA were altered by SigE overexpression. Acetyl-CoA, citrate, cis-aconitate, and isocitrate were increased by 1.3–2.0-fold in the GOX50 strain compared with the GT strain (Fig. 6 and supplemental Table S3). Conversely, malate in the GOX50 strain decreased to about 75% of levels of the parental GT strain (Fig. 6 and supplemental Table S3). It was also found that UDP-glucose and several cofactors, such as FAD, GDP, dCTP, or dGTP, were increased by SigE overexpression (supplemental Table S3).

FIGURE 6.

Levels of metabolites of the TCA cycle and acetyl-CoA in the GT and GOX50 strains under light conditions. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from independent experiments (n = 4–8). The levels were calibrated relative to the value obtained in the GT strain under light conditions, which was set at 100%. Differences between GT and GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005).

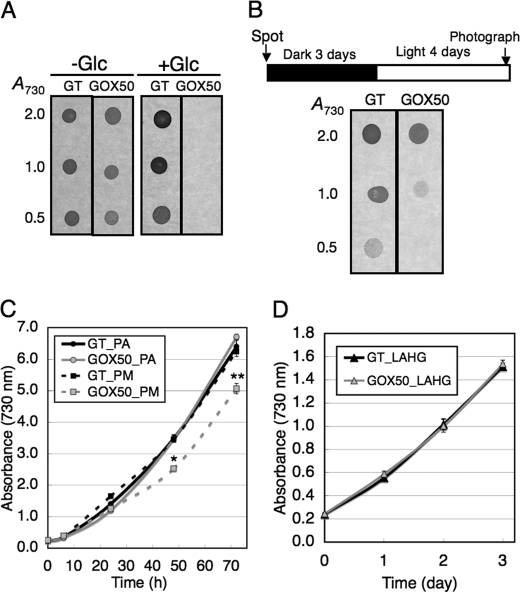

SigE-overexpressing Strain Exhibited Glucose and Dark-sensitive Phenotypes

Following the analyses at the transcript, protein, and metabolite levels, the physiological phenotypes associated with sugar catabolism were analyzed in GOX50. A previous study showed that mutants of glycolytic enzymes could not grow in the presence of glucose (23). The GT and GOX50 strains were cultivated with or without 5 mm glucose on solid medium. The results showed that overexpression of SigE abolished survival in the presence of glucose (Fig. 7A). Viability under dark conditions was also measured, because sugar catabolism is essential for heterotrophic growth. Both the GT and GOX50 strains were spotted onto modified BG-11 plates (without glucose) and cultured under dark conditions for 3 days and then transferred to light growth conditions. The results showed that SigE overexpression reduced viability under dark conditions (Fig. 7B). The growth curves under photoautotrophic, photomixotrophic, and light-activated heterotrophic conditions were generated (Fig. 7, C and D). The results showed that the growth under photomixotrophic conditions was delayed by SigE overexpression, whereas there was no effect under photoautotrophic and light-activated heterotrophic conditions (Fig. 7, C and D).

FIGURE 7.

Phenotypic analysis of the SigE overexpression strain. A, cultures of the GT and GOX50 cells were spotted onto modified BG-11 plates with/without 5 mm glucose. Each spot consisted of 2 μl of culture diluted to an A730 of 2.0, 1.0, or 0.5 as indicated. The plates were incubated in the light and photographed 4 days after inoculation. B, cells were spotted onto plates as in A, incubated in continuous darkness for 3 days, and then transferred to the light. Plates were photographed 4 days after the shift from dark to light. C, growth curves of cells under photoautotrophic (PA) or photomixotrophic (PM) conditions. For photomixotrophic conditions, 1 mm glucose was supplemented in modified BG-11 liquid medium. Data represent means ± S.D. of values from three independent experiments. Differences between GT and GOX50 analyzed using Student's t test were statistically significant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005). D, growth curves of cells under light-activated heterotrophic conditions (LAHG). The cells were grown in modified BG-11 liquid medium with 1 mm glucose. The cells were grown under continuous dark conditions, except for exposure to white light for 15 min per day.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated a strain overexpressing SigE, and the data showed that sugar catabolism is widely regulated by SigE at the transcript, protein, metabolite, and phenotype levels. The results indicate that RNA polymerase σ factor SigE plays pivotal roles in the transcriptional control of genes involved in primary carbon metabolism in this unicellular cyanobacterium.

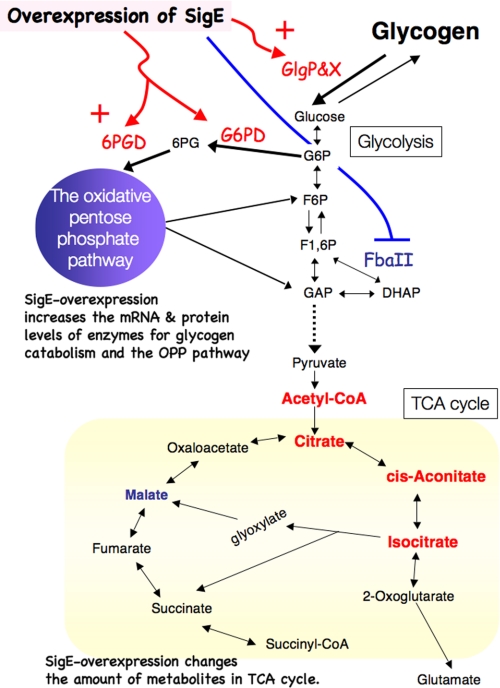

The transcriptome analysis showed that expressions of genes for four of the OPP pathway enzymes and two glycogen catabolism enzymes were increased by SigE overexpression; however, the expressions of three glycolytic genes (pfkA (sll1196), gap1, and pyk1) did not change (Fig. 8 and supplemental Table S2). These results demonstrate the complex regulation of the expressions of glycolytic genes. Recent studies showed that disruption of a histidine kinase, Hik8, or a response regulator, Rre37, resulted in decreased transcript levels of glycolytic genes (24–26), indicating that multiple transcriptional regulators control expressions of glycolytic genes. In contrast to enzymes of the OPP pathway and glycogen catabolism, FbaII was reduced by SigE overexpression (supplemental Fig. S3). Considering the metabolic flux, the down-regulation of FbaII may be favorable for activation of sugar catabolism, especially glucose degradation, through the OPP pathway (Fig. 8). It is noteworthy that Rre37 is a positive regulator for the upper half of glycolysis, including FbaII (25, 26). Thus, the ratio of glucose degradation through glycolysis or the OPP pathway may be determined by a balance between Rre37 and SigE. Summerfield and Sherman (27) also revealed that other group 2 σ factors, SigB and SigD, regulate the expressions of sugar catabolic genes, including fbaII and gnd, in response to light/dark transition. Further analysis is required to unravel the coordinated regulation of sugar catabolic genes and metabolic flux by various transcriptional regulators.

FIGURE 8.

Schematic model for changes of sugar catabolism caused by overexpression of SigE. The transcriptions of genes for glycogen catabolism and the OPP pathway are up-regulated by overexpression of SigE. Increased protein levels of the enzymes of glycogen catabolism and the OPP pathway enhance glycogen degradation. FbaII is down-regulated by SigE overexpression. The up-regulation of sugar catabolism changes metabolite levels in the TCA cycle. Enzymes or metabolites that increase or decrease by the overexpression of SigE are shown in red or blue, respectively. G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; F1,6P, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 6PG, 6-phosphogluconate.

In addition to transcriptional control, post-translational regulation of SigE and enzymes regulated by SigE were controlled by light status. SigE is repressed by ChlH, an H-subunit of magnesium chelatase, by protein-protein interaction under light conditions and is transiently activated under dark conditions (17). Glc-6-PD is up-regulated by OpcA through protein-protein interaction (10), although there have been no reports concerning post-translational control of 6PGD in cyanobacteria. Although the transcript levels of zwf and gnd in the GT strain diminished 1 day after light-to-dark transition, the proteins remained under prolonged dark conditions (Fig. 4), revealing no correlation between the mRNA and protein levels. Our results showing that Glc-6-PD enzymatic activity is increased by light-to-dark transition but that 6PGD activity is not may reflect the difference between their post-translational regulations. OpcA promotes oligomerization of Glc-6-PD (28); thus, the ratio of the oligomeric form of Glc-6-PD may be increased by light-to-dark conditions or by SigE overexpression. Proteomic studies also revealed that glycogen phosphorylase and FbaII of Synechocystis 6803 are targets of thioredoxin, a small protein involved in disulfide/dithiol reactions (29, 30). Disruption of thioredoxin systems in Synechocystis results in defects in adaptation to light and redox changes (30). Thus, integrative analysis of transcriptional to post-translational regulation of sugar catabolic enzymes indicates their significance for light adaptation in cyanobacteria. SigE also has some roles under high salt or heat shock conditions, in concert with other group 2 σ factors (31, 32), suggesting the importance of σ networks to survival during various environmental conditions.

CE/MS analysis revealed that metabolite levels upstream of sugar catabolism were not significantly affected, whereas those downstream of sugar catabolism, the TCA cycle and acetyl-CoA, were changed by SigE overexpression (Fig. 6 and supplemental Table S3). These results suggest that metabolites downstream of sugar catabolism have flexibility in their pool sizes, compared with upstream metabolites. Escherichia coli cells show tolerance to drastic changes in metabolic flux and energy production, because of the considerable elasticity in permitted pool sizes for pyruvate and acetyl-CoA (33). However, elevated sugar phosphates lead to growth inhibition and loss of viability of E. coli cells (34). Thus, metabolite levels of sugar phosphates in cyanobacteria might also be robustly controlled because of their toxicity, similarly to enteric bacteria. A glucose-sensitive mutant lacking pmgA (sll1968), a gene named from its defect in survival under photomixotrophic growth conditions and encoding a functionally unknown protein, showed increased levels of isocitrate under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions (2). Takahashi et al. (2) also found that levels of malate, succinate, and 2-oxoglutarate were increased by pmgA knock-out under photoautotrophic conditions. Combined with our data, these results suggest that an aberrant TCA cycle might cause the defect in glucose resistance observed in Synechocystis 6803 cells, suggesting that the integrity of TCA cycle is significant for mixotrophic growth of unicellular cyanobacteria. In consequence, expansion of cyanobacterial metabolomics will be vital for revealing the causes of phenotypes, providing deeper understanding of the physiology of cyanobacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by Edanz Group Japan (language-editing service) in the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science fellows from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to T. O.), grant-in-aid for scientific research for plant graduate students from the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (to T. O. and M. A.), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and grant-in-aid for CREST (project name “Elucidation of Amino Acid Metabolism in Plants Based on Integrated Omics Analyses”) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (to M. Y. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S4 and Figs. S1–S3.

- OPP

- oxidative pentose phosphate

- CE/MS

- capillary electrophoresis/mass spectrometry

- Glc-6-PD

- glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GT

- glucose-tolerant

- 6PGD

- 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase

- DIG

- digoxigenin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaneko T., Sato S., Kotani H., Tanaka A., Asamizu E., Nakamura Y., Miyajima N., Hirosawa M., Sugiura M., Sasamoto S., Kimura T., Hosouchi T., Matsuno A., Muraki A., Nakazaki N., Naruo K., Okumura S., Shimpo S., Takeuchi C., Wada T., Watanabe A., Yamada M., Yasuda M., Tabata S. (1996) DNA Res. 3, 185–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahashi H., Uchimiya H., Hihara Y. (2008) J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3009–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laurent S., Jang J., Janicki A., Zhang C. C., Bédu S. (2008) Microbiology 154, 2161–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenhut M., Huege J., Schwarz D., Bauwe H., Kopka J., Hagemann M. (2008) Plant Physiol. 148, 2109–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schaaff I., Heinisch J., Zimmermann F. K. (1989) Yeast 5, 285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yanagisawa S., Akiyama A., Kisaka H., Uchimiya H., Miwa T. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7833–7838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osanai T., Azuma M., Tanaka K. (2007) Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fu J., Xu X. (2006) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 260, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang C., Hua Q., Shimizu K. (2002) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58, 813–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hagen K. D., Meeks J. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11477–11486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Min H., Golden S. S. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 6214–6221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Osanai T., Kanesaki Y., Nakano T., Takahashi H., Asayama M., Shirai M., Kanehisa M., Suzuki I., Murata N., Tanaka K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30653–30659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kucho K., Okamoto K., Tsuchiya Y., Nomura S., Nango M., Kanehisa M., Ishiura M. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 2190–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Osanai T., Imamura S., Asayama M., Shirai M., Suzuki I., Murata N., Tanaka K. (2006) DNA Res. 13, 185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka K., Takayanagi Y., Fujita N., Ishihama A., Takahashi H. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3511–3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osanai T., Ikeuchi M., Tanaka K. (2008) Physiol. Plant. 133, 490–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Osanai T., Imashimizu M., Seki A., Sato S., Tabata S., Imamura S., Asayama M., Ikeuchi M., Tanaka K. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6860–6865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams J. G. (1988) Methods Enzymol. 167, 766–778 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rippka R. (1988) Methods Enzymol. 167, 3–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Satoh S., Ikeuchi M., Mimuro M., Tanaka A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4293–4297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Los D. A., Ray M. K., Murata N. (1997) Mol. Microbiol. 25, 1167–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ohkama-Ohtsu N., Oikawa A., Zhao P., Xiang C., Saito K., Oliver D. J. (2008) Plant Physiol. 148, 1603–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koksharova O., Schubert M., Shestakov S., Cerff R. (1998) Plant Mol. Biol. 36, 183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singh A. K., Sherman L. A. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 2368–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tabei Y., Okada K., Tsuzuki M. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355, 1045–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azuma M., Osanai T., Hirai M. Y., Tanaka K. (2011) Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 404–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Summerfield T. C., Sherman L. A. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 7829–7840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sundaram S., Karakaya H., Scanlan D. J., Mann N. H. (1998) Microbiology 144, 1549–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perez-Perez M. E., Florencio F. J., Lindahl M. (2006) Proteomics 1, (suppl.) 186–195 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pérez-Pérez M. E., Martín-Figueroa E., Florencio F. J. (2009) Mol. Plant 2, 270–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singh A. K., Summerfield T. C., Li H., Sherman L. A. (2006) Arch. Microbiol. 186, 273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pollari M., Gunnelius L., Tuominen I., Ruotsalainen V., Tyystjärvi E., Salminen T., Tyystjärvi T. (2008) Plant Physiol. 147, 1994–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Causey T. B., Shanmugam K. T., Yomano L. P., Ingram L. O. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2235–2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kadner R. J., Murphy G. P., Stephens C. M. (1992) J. Gen. Microbiol. 138, 2007–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.