Abstract

Background:

We aimed to investigate neurological outcomes in elderly patients with multiple trauma, and to review their clinical outcomes following neurosurgical operations.

Patients and Methods:

The study was conducted in a regional trauma center in Hong Kong. We collected prospective data on consecutive trauma patients from January 2001 to December 2008. Patients with multiple trauma (as defined by Injury Severity Score of 15 or more), with both head injury and extracranial injury, were included for analysis.

Results:

Age over 65 years, admission Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and Injury Severity Score were significantly poor prognostic factors in logistic regression analysis. Eleven (32%) of the 34 patients aged over 65 who underwent neurosurgical operations attained favorable neurological outcomes (GCS 4-5) at 6 months.

Conclusions:

Age was an important prognostic factor in multiple trauma patients requiring neurosurgical operations. Future randomized controlled clinical trials should be designed to recruit elderly patients (such as age between 65 and 75 years) at clinical equipoise for traumatic hematoma (such as subdural hematoma or traumatic intracerebral hematoma) evacuation and assess the quality of life, neurological, and cognitive outcomes.

Keywords: Elderly, mortality, multiple trauma, neurological outcomes, traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury represents one of the most significant factors for disability (from neurocognitive deficit and behavioral problem) and mortality (from refractory raised intracranial pressure and brain stem failure) in multiple trauma patients. Previous studies of multiple trauma patients associated with head injury have demonstrated that increasing age is an independent predictor of mortality.[1–3] Shackford et al. found that central nervous injury was responsible for 48% of all trauma death.[2] Gennarelli et al. found that 34% of trauma patients sustained concomitant traumatic brain injury and mortality of trauma patients with traumatic brain injury (15%) tripled that of those without traumatic brain injury (5%).[1] Most studies reported neurological outcomes of traumatic brain injury patients with inclusion of multiple trauma as a risk factor and data on neurological outcomes among elderly multiple trauma patients associated with traumatic brain injury were few in the literature.[4–19] In multiple trauma patients, secondary brain injuries were found in two-third of patients dying of traumatic brain injuries despite rapid transport and evacuation of mass lesions. Age has also been established as a prognostic factor for isolated head injury.[4–10] Increasing age is not only a poor prognostic factor in survival, but also an independent predictor of poor outcome after multiple trauma and head injury, through similar mechanisms of decline in physiological reserve, presence of comorbidity, and increased likelihood of developing intracranial hematomas.[11–19] Also, in contrast to younger patients, fall was the commonest cause of injury, rather than vehicle-related. Half of the elderly patients actually suffered from major trauma.

Life expectancy is expected to increase in the coming years with the advance of medical technology. In the United States, it is expected that more than one-fifth of the population will be aged over 65 by the year 2040. In Hong Kong, it is projected that the population aged over 65 will increase from 12% to 26% by 2036.[20] There is a lack of data in the literature on neurological outcomes and disability in Chinese elderly multiple trauma patients with associated head injury. We hypothesized that age over 65 was a poor prognostic factor in Hong Kong Chinese patients with multiple trauma and head injury, and secondarily aimed to assess clinical outcomes following neurosurgical operations.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in a regional trauma center in Hong Kong, which provides emergency neurosurgical care for a quarter of the population of Hong Kong. A trauma database is maintained with comprehensive details of all trauma patients admitted via the Emergency Department (ED) trauma rooms.

We retrospectively reviewed data on trauma patients, collected prospectively between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2008. We included patients aged over 65 years with multiple trauma (as defined by Injury Severity Score [ISS] ≥ 15 with two or more Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] ≥ 2 on admission) and head injury (as defined by head Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] of ≥ 2 on admission) for analysis. In-hospital data relating to the mechanism of injury, sex, age, comorbidity, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score on admission, initial systolic blood pressure (SBP), initial unassisted respiratory rate (RR), Revised Trauma Score (RTS), ISS, AIS of different regions, and computed tomographic findings of intracranial hematoma, were retrieved for analysis.[21–24] Neurosurgical operative records were retrieved and reviewed retrospectively.

The primary outcome was the neurological outcome at 6 months postinjury, as measured by the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS).[25] The GOS measures global functioning as a combination of neurological function and dependence on others, with five outcome categories ranking 1-5: death (1), persistent vegetative state (2), severe disability (conscious but dependent on others for daily activities) (3), moderate disability (disabled but independent in daily activity) (4), and good recovery (5). We completed the outcome measure at discharge and at 6 months, using telephone interviews conducted by trained research assistants. Incomplete data collection or loss of follow-up happened in 16 (6%) patients and they were excluded from further analysis. Favorable outcomes at 6 months included good recovery and moderate disability. Unfavorable outcomes at 6 months included severe disability, persistent vegetative state and death.

The data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data are presented as percentages for categorical data, means with standard deviations for continuous data, and medians with interquartile ranges for ordinal data. Factors considered include male sex, elderly (age ≥ 65 years), admission GCS, admission ISS, admission SBP, admission RR, and the presence of medical comorbidity. Univariate statistical analyses were performed using contingency analysis (the Pearson Chi-square test and the Fisher exact test) for categorical data, and the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous data. The three significant factors (elderly, admission GCS, and admission ISS) were included for subsequent multivariable statistical analyses with multiple logistic regression using the ‘enter’ method, and results are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was taken as a two-tailed P-value of 0.05 or less, and a trend was suggested by a two-tailed P-value between 0.05 and 0.10.

RESULTS

Patients requiring emergency neurosurgical operations

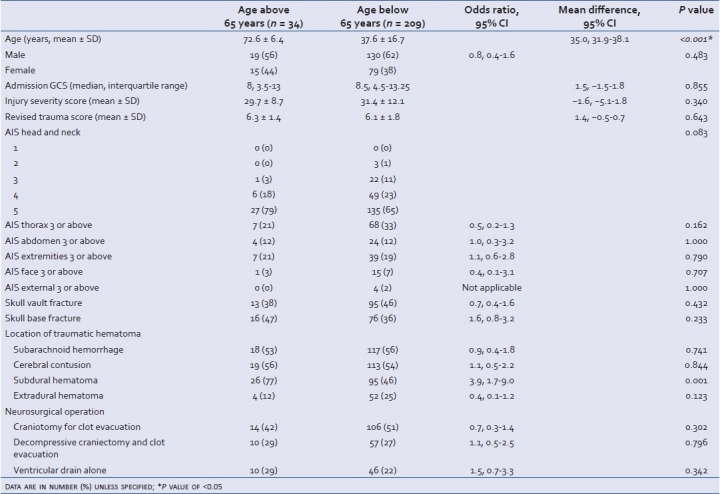

A total of 243 patients underwent emergency neurosurgical operations during the 8-year period. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in admission GCS, ISS, and RTS between patients aged over and below 65 years. The most common associated injuries, other than head and neck, were thoracic injuries.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of multiple trauma patients requiring emergency neurosurgical operations

Six-month neurological outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Age over 65 years was a significantly independent prognostic factor for neurological outcomes (odds ratio 0.21, 95% CI: 0.09-0.52) and mortality (odds ratio 3.9, 95% CI: 1.5-9.7), after multiple logistic regression. Other significant prognostic factors for neurological outcomes were ISS (odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94-0.99) and admission GCS (odds ratio 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1-1.3). Similarly, other significant prognostic factors for mortality were ISS (odds ratio 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02-1.08) and admission GCS (odds ratio 0.89, 95% CI: 0.82-0.97).

Table 2.

Six-month neurological outcomes of multiple trauma patients requiring emergency neurosurgical operations

Emergency neurosurgical operations in patients aged over 65 years

Thirty-four patients were aged over 65 years. Age (mean ± SD) was 72.6 ± 6.4 years and 56% were male. Medical comorbidities were present in 11 (32%) patients. Falls at the ground level or from less than 1 m accounted for 50% of cases, and pedestrian involvement accounted for another 32% of cases. Admission GCS (median, interquartile range) was 8.5, 4.5-13.25, and 17 (50%) patients sustained a coma-producing severe head injury. ISS (mean ± SD) was 29.7 ± 8.7 and RTS (mean ± SD) was 6.3 ± 1.4.

Thirteen (38%) patients had skull vault fractures and 16 (47%) had skull base fractures. Most patients (32, 94%) had combinations of different intracranial hematomas, with subdural hematomas (26, 77%), cerebral contusions (19, 56%), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (18, 53%). No patients aged over 65 suffered from isolated extradural hematoma. Ten (29%) patients had burr hole and ventriculostomy alone, and 24 (71%) patients had craniotomy for clot evacuation. Additional craniectomy was performed on ten (29%) patients to control intracranial hypertension.

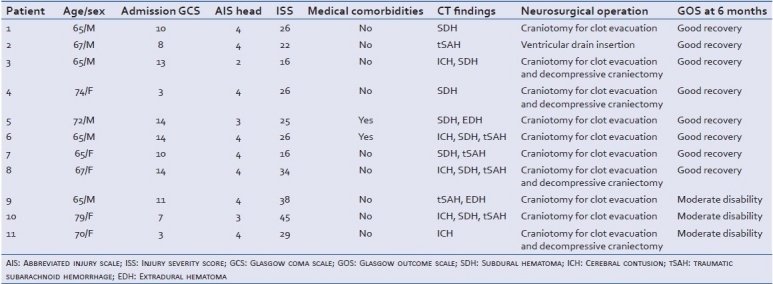

Eleven (32%) patients attained favorable neurological outcomes at 6 months, including two patients with an initial GCS score of 3/15. Clinical profiles are presented in Table 3. Sixteen (47%) patients died or remained in a vegetative state at 6 months.

Table 3.

Profile of elderly multiple trauma patients yielding favorable neurological outcomes at 6 months, following emergency neurosurgical operation

DISCUSSION

In this study, we confirmed that advancing age was a poor prognostic factor in multiple trauma patients who required neurosurgical operations. Nevertheless, one-third of patients aged over 65 regained independence, including patients presenting with coma-producing severe head injury. Thus, long-term favorable neurological outcomes can still be achieved after a course of dedicated neurorehabilitation in selected elderly multiple trauma patients. This was, in contrast to some previous published studies, in which none of the comatose traumatic brain injury patients aged above 70 years achieved good recovery and only 1% achieved independency in activity of daily living.[14,15] Kilaru et al. reported that all traumatic brain injury patients aged 65 years or above with admission GCS 3/15 died.[26] The outcome of a selected group of patients, with severe traumatic brain injury who had GCS scores of 3 or 4 and were over 65 years old, was also reported, in which favorable outcomes could be achieved in some of these patients.[27] With aggressive neurosurgical and neurointensive care, we were able to achieve independency in activity of daily living in two similar patients. More recently, Gan et al. reported that 23% of elderly aged 64 years or above could achieve good outcome after moderate or severe traumatic brain injury,[11] concurring that some of these elderly patients could achieve favorable outcome with active neurosurgical and neurointensive management. Our results also concurred with previous studies that age was a strong prognostic predictor.[12,28]

A recent article from the MRC Corticosteroid Randomization After Significant Head Injury (CRASH) trial collaborators presented the predictive factors for outcomes after traumatic brain injury in a cohort of 10,008 patients.[29] The researchers took the opportunity of the CRASH trial to develop a prognostic model for head injury. They identified age as an independent predictive factor for mortality at 14 days, and death or severe disability at 6 months. This basic model (demographic and clinical variables only) included age, GCS, pupil reactivity, and the presence of extracranial injury. This was the first model to include the presence of extracranial injury in a prognostic model for traumatic brain injury. Moreover, this model pioneered the recognition of a distinct and poorer outcome of traumatic brain injury in multiple trauma elderly patients.

Fall-related injuries are among the most serious, and most common, medical problems experienced by older people.[30,31] Internationally, injuries are a leading cause of death in the elderly, and falls constitute a high proportion of accidental deaths.[29,30] Common underlying causes and risk factors for falls include muscle weakness, gait and balance problems, visual impairment, cognitive impairment, depression, functional decline, and medications.[32] In this study, 50% of multiple trauma patients aged over 65 years required neurosurgical operations due to a fall from less than 1 m or on the level ground. This finding, in association with other injuries caused by falls in the elderly,[19] should highlight the need for community awareness in advancing preventive measures. Current evidences suggested that tai chi group exercise, muscle strengthening and balance retraining, home hazard assessment and modification, withdrawal of psychotrophic medications, and cardiac pacing for patients with cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity were effective to prevent fall and should be considered in the community preventive and education programs.[33,34]

Weakness of this single-center study includes a long study period and the relatively smaller sample of elderly patients. Nevertheless, we were able to confirm the poor prognostic effect of age and describe the management outcome of elderly multiple trauma patients with neurosurgical operations.

CONCLUSION

Age was an important prognostic factor in multiple trauma patients requiring neurosurgical operations. Future randomized controlled clinical trials should be designed to recruit elderly patients (such as age between 65 and 75 years) at clinical equipoise for traumatic hematoma (such as subdural hematoma or traumatic intracerebral hematoma) evacuation and assess the quality of life, neurological, and cognitive outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

G Wong, WS Poon, J Yeung, and T Rainer designed the current study. G Wong, E Ng, and J Yeung were responsible for data acquisition. G Wong performed the data analysis. G Wong, E Ng, and C Graham drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to the critical revision of the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gennarelli TA, Champion HR, Copes WS, Sacco WJ. Comparison of mortality, morbidity, and severity of 59,713 head injured patients with 114,447 patients with extracranial injuries. J Trauma. 1994;37:962–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199412000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shackford SR, Mackersie RC, Davis JW, Wolf PL, Hoyt DB. Epidemiology and pathology of traumatic deaths occurring at a level trauma center in a regionalized system: The importance of secondary brain injury. J Trauma. 1989;29:1392–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198910000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shackford SR, Mackersie RC, Holbrook TL, Davis JW, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, Hoyt DB, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic death. A population-based analysis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:571–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170107016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demetriades D, Sava J, Alo K, Newton E, Velmahos GC, Murray JA, et al. Old age as a criterion for trauma team activation. J Trauma. 2001;51:754–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Habbema JD, Farace E, Marmarou A, Murray GD, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: Development and validation of a prognostic score based on development and validation of a prognostic score based on admission characteristics. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1025–39. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhne CA, Ruchholtz S, Kaiser GM, Nast-Kolb D. Working group on multiple trauma of the German Society of Trauma. Mortality in severely injured elderly trauma patients - when does age become a risk factor? World J Surg. 2005;29:1476–82. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7796-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perdue PW, Watts DD, Kaufmann CR, Trask AL. Differences in mortality between elderly and younger adult trauma patients: Geriatric status increases risk of delayed death. J Trauma. 1998;45:805–10. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perel P, Edwards P, Wentz R, Roberts I. Systematic review of prognostic models in traumatic brain injury. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Signorini DF, Andrews PJ, Jones PA, Wardlaw JM, Miller JD. Predicting survival using simple clinical variables: A case study in traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:20–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Sluis CK, Klasen HJ, Eisma WH, ten Duis HJ. Major trauma in young and old: What is the difference? J Trauma. 1996;40:78–82. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199601000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan BK, Lim JH, Ng IH. Outcome of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury amongst the elderly in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosenthal AC, Lavery RF, Addis M, Kaul S, Ross S, Marburger R, et al. Isolated traumatic brain injury: Age is an independent predictor of mortality and early outcome. J Trauma. 2002;52:907–11. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200205000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munro PT, Smith RD, Parke TR. Effect of patients’ age on management of acute intracranial haematoma: Prospective national study. BMJ. 2002;325:1001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7371.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ushewokunze S, Nannapaneni R, Gregson BA, Stobbart L, Chambers IR, Mendelow AD. Elderly patients with severe head injury in coma from the outset - has anything changed? Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:604–7. doi: 10.1080/02688690400022763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vollmer DG, Torner JC, Jane JA, Sadovnic B, Charlebois D, Eisenberg HM, et al. Age and outcome following traumatic comas: Why do older patients fare worse? J Neurosurg. 1991;5:S37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon WS, Zhu XL, Ng SC, Wong GK. Predicting one year clinical outcome in traumatic brain injury (TBI) at the beginning of rehabilitation. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;83:207–8. doi: 10.1007/3-211-27577-0_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong GK, Hung YW, Chong C, Yeung J, Chi-Ping Ng S, Rainer T, et al. Assessing the neurological outcome of traumatic acute subdural hematoma patients with and without primary decompressive craniectomies. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2010;106:235–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-98811-4_44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong GK, Tang BY, Yeung JH, Collins G, Rainer T, Ng SC, et al. Traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage: Is the CT pattern related to outcome? Br J Neurosurg. 2009;23:601–5. doi: 10.3109/02688690902948184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeung JH, Chang AL, Ho W, So FL, Graham CA, Cheng B, et al. High risk trauma in older adults in Hong Kong: A multicentre study. Injury. 2008;39:1034–41. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong Kong: Hospital Authority Statistics and Health Information Section. Hospital Authority Report (2007-2008); 2008. Hospital Authority. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Des Plaines, IL: American Association for Automotive Medicine (AAAM); 2005. Association for the Advancement of Automobile Medicine. The Abbreviated Injury Scale-2005 Version. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: A method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:181–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Champion HR, Sacco MJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennarelli TA, Flanagan ME. A revision of the trauma score. J Trauma. 1989;29:623–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilaru S, Garb J, Emhoff T, Fiallo V, Simon B, Swiencicki T, et al. Long-term functional status and mortality of elderly patients with severe closed head injuries. J Trauma. 1996;41:957–63. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brazinova A, Mauritz W, Leitgeb J, Wilbacher I, Majdan M, Janciak I, et al. Outcomes of patients with severe traumatic brain injury who have Glasgow Coma Scale of 3 or 4 and are over 65 years old. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1549–55. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhullar IS, Roberts EE, Brown L, Lipei H. The effect of age on blunt traumatic brain-injured patients. Am Surg. 2010;76:966–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perel P, Arango M, Clayton T, Edwards P, Komolafe E, et al. MRC CRASH Trial Collaborators. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: Practical prognostic models based on a large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336:425–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39461.643438.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elkington J. The big fall issue. N S W Public Health Bull. 2002;13:2. doi: 10.1071/nb02002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Sievanen H. Alarming rise in fall-induced severe head injuries among elderly people. Injury. 2007;38:957–63. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubinstein LZ, Josephson KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:141–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. WITHDRAWN: Intervention for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD000340. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000340.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Logan PA, Coupland CA, Gladman JR, Sahota O, Stoner-Hobbs V, Robertson K, et al. Community falls prevention for people who call an emergency ambulance after a fall: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c2102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]