Abstract

Background:

Emergency departments (ED) frequently evaluate patients with probable ectopic pregnancies who go home and may rupture. It would be beneficial to know which patient factors are associated with rupture and which are not.

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to determine which ED patients with ectopic pregnancies are at risk for rupture.

Materials and Methods:

This study was a retrospective chart review of all women aged ≥18 years during a 5-year period who were diagnosed with ectopic pregnancy to a level I ED. Data collected included basic demographic information, medical, surgical, obstetric and gynecologic history, social and sexual history, findings on physical examination, and laboratory values such as urine pregnancy test, β-hCG, and complete blood count.

Results:

There was a significant difference using a multivariate regression analysis with 95% CI in history findings of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and urinary tract symptoms. There was a significant difference in physical examination of pulse, diastolic pressure, abdominal tenderness, peritoneal signs, cervical motion tenderness, and adnexal tenderness. There was also a significant difference in β-hCG, hemoglobin and hematocrit results and ultrasound findings of free peritoneal fluid, intrauterine pregnancy and cardiac findings between those who ruptured and those who did not. None of these tests was able to differentiate those that would go on to rupture.

Conclusion:

The result of the study did not find any single sign, symptom, or test that could reliably differentiate patients who have a ruptured ectopic from those who do not. However, β-hCG over 1500 mIU was the best variable in explaining the variation between those who would or would not go on to rupture after their ED visit.

Keywords: Ectopic, emergency department, rupture

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is 2% of all pregnancies in the United States, and it is one of the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths during first trimester in women of childbearing age.[1–3] During the past few decades, the occurrence of this condition has increased from 4.5 per 1000 pregnancies in 1970 to an estimated 19.7 per 1000 pregnancies in 1992.[4] The increasing occurrence of this condition is concerning because of an associated increase in morbidity and mortality rates. Ectopics cause 13% of all pregnancy-related deaths and are the leading cause of maternal death in African-American women.[5]

In spite of the comparatively high occurrence of ectopic pregnancy, early detection can be difficult. Unless considered in the differential diagnosis, ectopic pregnancy can go unidentified at the initial medical evaluation. While the incidence of ectopic pregnancy in the general population is about 2%, the prevalence among pregnant patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) with first-trimester bleeding, pain or both, is 6-16%.[4]

Studies have found that the historical features, physical examination, and laboratory parameters are of limited values in identifying patients with minimal symptomatology who are at risk for an ectopic pregnancy. However, β-hCG was found to be an essential tool in evaluating potential ectopic pregnancy in these patients.[6] Since most pregnant patients will have a β-hCG < 1500 at some point in their pregnancy, the researchers quantified the increased risk of ectopic pregnancy in patients with β-hCG < 1500 mlU/ml by comparing β-hCG distribution of symptomatic women with ectopic pregnancy, abnormal intrauterine pregnancy, and normal intrauterine pregnancy.[6,7] A below-threshold β-hCG levels < 1500 mlU/ml doubled the pretest odds of ectopic pregnancy and was extremely useful at separating all abnormal pregnancies from normal intrauterine pregnancies.[7–9] A protocol of quantitative hCG levels < 1500 mIU/ml, combined with transvaginal ultrasound, has been proposed in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy with 100% sensitivity and 99.9% specificity.[10–16]

Patients presenting to the ED with abdominal pain and/or vaginal bleeding are more likely to have normal pregnancies than an ectopic pregnancy. Unfortunately, many of these patients are sent home from the ED and may go on to rupture. From a clinical perspective, is there the ability to rely on the results of an ED assessment to tell who is at risk for rupture? The purpose of this study was to evaluate the indicators for rupture for patients who present to the ED with an ectopic pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study using a chart review of all women who had an ectopic pregnancy that presented to a level I, community inner city teaching hospital ED with 60,000 visits per year. The charts were reviewed from 2000 to 2005. The inclusion criteria included women aged ≥18 years old who presented with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding to the ED and who were determined to have an ectopic pregnancy. The exclusion criteria were women aged <18 years old and patients who presented with complaints other than abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding and who were found to have other diagnoses. Women with significant data elements missing from their charts were excluded from the analysis.

The data were collected from the ED, hospitalization records, and outpatient clinics over a 4-year period using a data collection sheet that included basic demographic information, history of the patient (including medical, surgical, obstetric and gynecologic history, as well as social and sexual history), findings on physical examination, and lab values (such as urine pregnancy test, β-hCG values and complete blood count).

The data were entered into SPSS statistical software (version 14) program, and an analysis of frequency distributions and multivariate regression was performed. Ectopic pregnancy patients with and without rupture at presentation or subsequent rupture were compared with respect to demographic, history and physical examination characteristics, and laboratory values (including β-hCG levels) in the ED and at follow-up. The shock index was calculated based on the vital signs upon presentation. The study was approved by the IRB to review only adult cases.

RESULTS

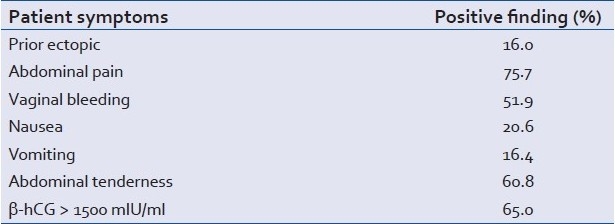

Of the 249 patients who had an ectopic pregnancy, 187 had complete data available for analysis. The demographic distribution of the patients was found to be 50% African-American, 47% Hispanic, 2% Caucasian, and 1% Asian. Most of the patients came from one of three sources: 74% were ED walk-in, 20% were referred from the hospital clinic, and 6% were referred from outside the hospital clinic. Patients had various symptoms [Table 1].

Table 1.

Physical exam results

A total of 49% of those presenting to the ED had a rupture, 26% did not, 4% were not recorded, and 17% were not diagnosed with ectopic at the ED visit [Table 2]. Out of those 154 patients with a β-hCG equal to or more than 1500 mIU/ml, 57% ruptured, 28% did not, and 10% were not diagnosed with ectopic during the ED visit. Further, 41% (29) of those who presented with a β-hCG of less than 1500 mIU/ml had a ruptured ectopic. Of the remaining patients with a β-hCG 1500 or less, 21% (15) did not rupture and 34% (24) were not diagnosed with an ectopic during the ED visit. No patient in this study population died as a result of an ectopic pregnancy; need for blood transfusion was not recorded. Of the patients who ruptured, the highest β-hCG was 146,174 mIU/ml, mean of 14,813 mIU/ml, mean hemoglobin of 11.5 g/dl and mean hematocrit of 34.5%. The ultrasound finding in the ruptured group revealed 76.7% with free peritoneal, 75.6% had adnexal mass, 13.4% had a yolk sac, and 10.1% had cardiac activity.

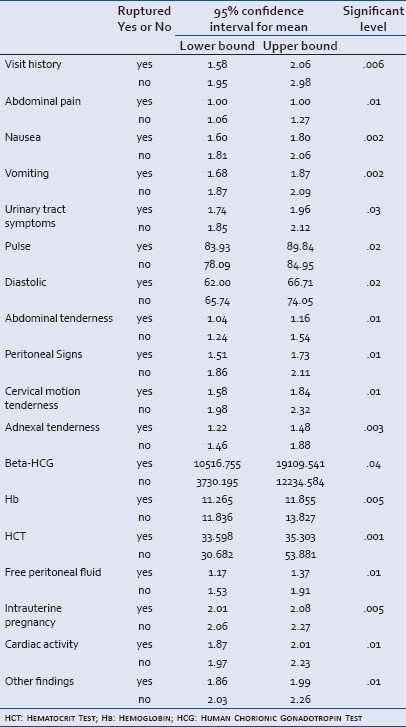

Table 2.

Variables with significance at .05 or less at Confidence Levels (95%) between those that ruptured

A number of factors did not demonstrate any difference between those who ruptured and those who did not at a significance level of 0.05. Prior history of sexually transmitted disease or pelvic inflammatory disease, complaints of syncope or vaginal bleeding and examination findings of systolic blood pressure, pulse and shock index were not found to be significant.

Using a multivariate regression analysis with 95% CI, there was a correlation between those who ruptured and those who did not in terms of patient history, physical exam, testing, and ultrasound findings. Presentation of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and urinary tract symptoms were found to be significant in the history. Pulse rate, diastolic blood pressure, abdominal tenderness, peritoneal signs, cervical motion tenderness, and adnexal tenderness were found to be significant in the physical exam [Table 1]. The testing of the β-hCG, hemoglobin, and hematocrit were significant, as were ultrasound findings of free peritoneal fluid, intrauterine pregnancy, and cardiac activity. Using a general linear regression model to examine which variables indicate the potential for rupture, similar variables were significant with an overall power of 79%. Prior tubular ligation (P=0.01), vaginal bleeding (P=0.01), nausea (P=0.04), systolic blood pressure (P=0.04), and β-hCG (P=0.00) were all significant indicators of potential to rupture. A β-hCG of 1500 mIU/ml or less variable having an R-squared of 67% [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

The study did not find any single sign, symptom, or test that could reliably be used to differentiate patients who have a ruptured ectopic. This was especially true for patients who presented to the ED with abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and a serum β-hCG levels < 1500 mIU/ml. These findings were consistent with those of Bickell and others who found that classic tubal pregnancy signs, and symptoms were not able to differentiate those who ruptured from those who did not.[17] However, they did find that rupture was the highest in patients with the shortest time interval between onset and treatment. On the other hand, Latchaw and others found that patients with a β-hCG of greater than or equal to 5000 mIU/ml with a prior history of ectopic were more likely to rupture.[18] Although the findings of those vital signs alone did not differentiate those who ruptured, we did find a correlation with shock index, as did Birkhahn and others.[19]

Many patients with suspected ectopic pregnancy were sent home from the ED to return in 2 days for a repeat β-hCG. These patients had the potential to rupture during this time. Although a β-hCG below 1500 mIU/ml was associated with rupture, the association was not strong enough to use is as a diagnostic criterion. This raises the question of the safety in sending patients home with a diagnosis of “rule out” ectopic pregnancy. Although we did not find mortality related in these patients, there is always a concern that sending possible ectopic patients home could result in adverse events. Future studies into the outcome of patients who are sent home from the ED with the diagnosis of vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy would be valuable.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study. The reliance on medical records and the information they contained may have affected the depth and type of information included in this study. The study was limited because some patients failed to follow up, some followed up at another institution, the data were not always complete, and some patients did not have the diagnosis of ectopic on the final diagnosis. Some data elements were not ascertained from the chart because they were not obtained or not recorded. The sample in this study had limited scope within the variables related to history and physical at the time of presentation to the ED. A sample with more variation within these factors could have lessened the significance of β levels in determining who would go on to rupture. The study was performed at one medical facility, which serves an inner city population. The results might have been different if conducted in another healthcare facility, such as a suburban ED.

CONCLUSIONS

From a clinical perspective, the results imply that an ED assessment may not be enough to tell which ectopic-presenting patients are at risk for rupture. Although a β-hCG level of 1500 mIU/ml or greater was significant in determining those who ruptured (57%), it did not discriminate among those who will rupture. Without a discriminating test for rupture, there is always a risk in discharging patients with a possible ectopic pregnancy, this study did not find any increase in mortality with the current practice.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Houry DE, Salhi BA. Acute complications of pregnancy. In: Marx JA, editor. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. chap 176. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:379–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0810384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Hospital Discharge Survey. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Jul, National Health Statistics Report, 2006. Report Number 5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray H, Baakdah H, Bardell T, Tulandi T. Diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. CMAJ. 2005;173:905–12. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slaughter JL, Grimes DA. Methotrexate therapy. Nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. West J Med. 1995;162:225–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedger JR, Jaub JJ, Armao JC. Detection of ectopic pregnancy in an outpatient population: The role of the beta-hCG level. J Emerg Med. 1984;2:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(84)90326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohn MA, Jerr K, Malkevich D, O’Neil N, Kerr MJ, Kaplan BC. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin levels and the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy in emergency department patients with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:119–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergner L. Race, health and health services. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:939. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.7.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledger WL, Sweeting VM, Chatterjee S. Rapid diagnosis of early ectopic pregnancy in an emergency gynecology service-are measurements of progesterone, intact and free beta human chorionic gonadotropin helpful? Hum Reprod. 1994;9:157–60. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valley VT, Mateer JR, Aiman EJ, Thoma ME, Phelan MB. Serum progesterone and endovaginal sonography by emergency physicians in the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:309–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnhart K, Mennuti MT, Benjamin I, Jacobson S, Goodman D, Coutifaris C. Prompt diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in an emergency department setting. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:1010–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipscomb GH, Stovall TG, Ling FW. Nonsurgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 343;1325:9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geoffrey G. Emergency medical service health services: The local perspective. Proc Acad Polit Sci. 1977;32:121–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson LS. Health care reform and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1566–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevino FM. Quality of health care for ethnic/racial minority populations. Ethn Health. 1999;4:153–64. doi: 10.1080/13557859998119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Counselman FL, Shaar GS, Heller RA, King DK. Quantitative B-HCG levels less than 1000mIU.mL in patients with ectopic pregnancy: Pelvic ultrasound still useful. J Emerg Med. 1988;16:699–703. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bickell NA, Bodian C, Anderson RM, Kase N. Time and risk of ruptured tubal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:789–94. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139912.65553.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latchaw G, Takacs P, Gaitan L, Geren S, Burzawa J. Risk factors associated with the rupture of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2005;60:177–80. doi: 10.1159/000088032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkhahn RH, Gaeta TJ, Van Deusen SK, Tloczkowski J. The ability of traditional vital signs and shock index to identify ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1293–6. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00663-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]