Abstract

Penetrating brain injury (PBI), though less prevalent than closed head trauma, carries a worse prognosis. The publication of Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury in 2001, attempted to standardize the management of PBI. This paper provides a precise and updated account of the medical and surgical management of these unique injuries which still present a significant challenge to practicing neurosurgeons worldwide. The management algorithms presented in this document are based on Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury and the recommendations are from literature published after 2001. Optimum management of PBI requires adequate comprehension of mechanism and pathophysiology of injury. Based on current evidence, we recommend computed tomography scanning as the neuroradiologic modality of choice for PBI patients. Cerebral angiography is recommended in patients with PBI, where there is a high suspicion of vascular injury. It is still debatable whether craniectomy or craniotomy is the best approach in PBI patients. The recent trend is toward a less aggressive debridement of deep-seated bone and missile fragments and a more aggressive antibiotic prophylaxis in an effort to improve outcomes. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks are common in PBI patients and surgical correction is recommended for those which do not close spontaneously or are refractory to CSF diversion through a ventricular or lumbar drain. The risk of post-traumatic epilepsy after PBI is high, and therefore, the use of prophylactic anticonvulsants is recommended. Advanced age, suicide attempts, associated coagulopathy, Glasgow coma scale score of 3 with bilaterally fixed and dilated pupils, and high initial intracranial pressure have been correlated with worse outcomes in PBI patients.

Keywords: Medical management, penetrating brain injury, surgical management

INTRODUCTION

Penetrating brain injury (PBI) includes all traumatic brain injuries which are not the result of a blunt mechanism.[1] Although less prevalent than closed head trauma, PBI carries a worse prognosis.[2] In civilian populations, PBIs are mostly caused by high velocity objects, which result in more complex injuries and high mortality.[3] PBI caused by non-missile, low-velocity objects represents a rare pathology among civilians, with better outcome because of more localized primary injury,[2,4] and is usually caused by violence, accidents, or even suicide attempts.[3–11]

Despite the efforts of law enforcement agencies, these injuries unfortunately continue to be frequently encountered in large trauma centers as well as in metropolitan and large community emergency departments.[1] The formulation of standard medical and surgical management algorithm for PBI patients is essential. In 1995, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Brain Trauma Foundation collaborated to formulate evidence-based Guidelines for the Management of Severe Head Injury[12] which were periodically revised and last updated as third edition in 2007.[13] However, they did not address the management of patients injured by penetrating objects such as gun shots and stab wounds. In the spring of 1998, the International Brain Injury Association, the Brain Injury Association, USA, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons began work on this task. Thus, Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury[14] was published in 2001, which attempted to standardize both the medical and surgical management of penetrating craniocerebral trauma. These guidelines were based on available literature at that time and have not been revised for almost a decade.

In this paper, we have reviewed the contemporary management guidelines of PBI. For this purpose, the current literature on various parameters related to PBI available on PubMed and MEDLINE was reviewed. The Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury was thoroughly evaluated and compared with literature published after 2001. The objective of this document is to provide a precise and updated account of the medical and surgical management of these unique injuries which still present a significant challenge to practicing neurosurgeons worldwide.

BALLISTIC PRINCIPLES AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PBI

Optimum management of PBI requires a good understanding of the mechanism of injury and its pathophysiology. As most of the PBIs are caused by missiles or projectiles, an understanding of ballistics is imperative. Ballistics is the study of the dynamics of projectiles; wound ballistics is the study of the projectile's action in tissue.[14]

The ability of bullets, shrapnel, and low-velocity objects such as knives and arrows to penetrate the brain is dependent on their energy, shape, the angle of approach, and the characteristics of intervening tissues (skull, muscle, mucosa, etc.).[1,14] Primary injury to the brain is determined by the ballistic properties (kinetic energy, mass, velocity, shape, etc.) of the projectile and any secondary projectiles, such as bone or metallic fragments.[14] The kinetic energy is defined by the relationship: E = 1/2mv2, which implies that the velocity of the projectile has a greater influence than the mass of the projectile alone.[1]

As the projectile travels through the brain parenchyma, it is preceded by a transient sonic wave (2 μs) which appears to have minimal influence on surrounding tissue.[15,16] The projectile itself, however, crushes the soft brain tissue in its path, creating a permanent track of injury. This is in addition to the secondary missiles such as bone and metal fragments created from the impact of projectile on the skull. Higher velocity projectiles will also impart an additional temporary cavitation effect in their wake, which is a velocity-related phenomenon. This results from the transmission of the kinetic energy of the projectile to the surrounding tissue, thus rapidly compressing it tangentially from the primary track. This temporary cavity then collapses upon itself only to re-expand in progressively smaller undulating wave-like patterns. Every cycle of temporary expansion and collapse creates significant surrounding tissue injury to the brain. This can result in shear-like injury of the neurons or can result in epidural hematomas, subdural hematomas, or parenchymal contusions.[17]

An important principle to understand is the influence of air-resistance on the ballistics of a missile. A projectile loses its kinetic energy rapidly as it travels through the air because of its resistance.[17] This loss of kinetic energy is related to the decrement in its velocity which in turn is dependent on the shape of the projectile. The sharper the nose of a bullet, the less the velocity will be decreased by air resistance. The rounder the nose of a bullet or more irregular the shape (as in shrapnel), the quicker the velocity slows and kinetic energy decreases. Projectiles traveling at higher velocities carry more kinetic energy, and thus cause more damage.[1] Additionally, a PBI is expected to be much more severe in case of a close range firearm injury as maximum amount of initial kinetic energy is transferred to the brain tissue.

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OF PBI

Immediately after arrival of the patient in the emergency department, a primary survey and stabilization of the patient with regard to the airway, breathing, cervical spine, and circulation including external hemorrhage should be achieved.[18] After resuscitation, an inspection of the superficial wound should be done. The skin, especially the scalp, must be examined meticulously for wounds as it may be covered by blood-matted hair.[18] An entrance wound should be identified and its location recorded as well as any exit wounds when they exist. The superficial scalp should also be observed for powder burns, which would imply a close range firearm injury.[1] Any CSF, bleeding, or brain parenchyma oozing from the wound should be noted; the size of the deficit should also be documented.[1] To examine the head and neck thoroughly, the cervical collar should be removed, but strict spine precautions must be employed. Hemotympanum suggests a skull base fracture. All orifices must be checked for retention of foreign bodies, the missile, teeth, and bone.[18,19] After careful examination of the wound, a detailed neurological examination should be performed, and the post-resuscitative glasgow coma scale (GCS) of the patients should be documented.[1] Clinical features suggestive of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) must be documented carefully. Neurological examination, which should be followed by a complete examination of other organ systems, is recommended as PBI patients may have multiple organ injuries.[18] A detailed medical history from family or friends and a chronology of the incidence from a witness is warranted. Initial laboratory evaluation must include an arterial blood gas, electrolytes, complete blood count, coagulation profile, type and cross match, and an alcohol and drug screen.[19] Once the initial evaluation is done, the patient should be transferred to radiology for a neuroimaging study as described in the following sections.

NEUROIMAGING IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PBI

The utility of various neuroimaging methods used in patients with PBI lies on the potential management and prognostic implications of these modalities.[20,21] Important findings include: entry and exit sites; intracranial fragments; missile track and its relationship to both blood vessels and air-containing skull-base structures; intracranial air; transventricular injury; basal ganglia and brain stem injury; missile track crossing the midline; multi-lobar injury; basal cisterns effacement; brain parenchymal herniation and associated mass effect.[20,21] Neuroimaging is vital for surgical decision making, the type of surgery, the size and site of craniotomy, the route for extraction of foreign body, etc. as well as the decision to choose non-surgical management, which is also not uncommon in PBI.

Plain films

Plain radiographs of the skull can be of considerable value in identifying the cranial wound(s), the location of missile and bone fragments, and the presence of intracranial air [Figure 1].[20] However, evaluating the projectile trajectory with plain radiographs alone can be misleading in the presence of intracranial ricocheting or fragmentation.[20] Besides, the availability of computed tomography (CT) scanning largely precludes the use of plain radiography, and it is not routinely recommended.

Figure 1.

The skull X - ray (antero - posterior view) is of a neurologically intact, young male patient who presented after a bomb exploded near a political rally. The patient was asymptomatic except for a small puncture wound on scalp, causing minimal bleeding. The skull X - ray was carried out to screen for foreign bodies. The patient was managed conservatively, and at 6 months clinical and radiological follow - up, he remained stable with no displacement of the intracranial shrapnel

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the head is now the primary modality used in the neuroradiologic evaluation of patients with PBI.[20] This is because CT scanning is quick and provides improved identification of in-driven bone and missile fragments, characterization of the missile trajectory, evaluation of the extent of brain injury, and detection of intracranial hematomas and mass effects [Figure 2].[20,22–26] All patients with craniocerebral gunshot injury should be imaged emergently with unenhanced CT regardless of whether or not there is evidence of penetration on clinical examination.[21] In addition to the standard axial views with bone and soft tissue windows, coronal and sagittal sections are also helpful for patients with skull base involvement or high convexity injuries.[20] Postoperatively, CT scan can be helpful in evaluating the development of intracranial hematomas, the presence of residual foreign body, and the extent of cerebral edema.[20,25,26]

Figure 2.

The computed tomography (CT) scan of brain showing left frontal penetrating injury causing multiple fractures and pneumocranium. Multiple bone fragments are displaced within brain parenchyma resulting in contusion and edema. This male patient, a blast victim, at presentation was localizing to pain and had right hemiparesis. He underwent craniotomy, debridement, including removal of superficial intracranial bone fragments, wound refashioning, and primary closure. Post - operative course was unremarkable and at 6 months follow - up, the patient was completely independent, although he had persistent mild hemiparesis

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally not recommended for use in the acute management of PBI, as it is time consuming and can be potentially dangerous when there are retained ferromagnetic objects because of possible movement of the object in response to the magnetic torque.[1,3] However, MRI can be a useful neuroradiologic modality, if the PBI is caused by a wooden object.[20,27]

CEREBRAL ANGIOGRAPHY

Cerebral angiography (either CT or catheter) is recommended in patients with PBI where there is an increased risk of vascular injury. This would include those cases where the wound's trajectory is through or near the Sylvian fissure (location of M1 and M2 segments of the middle cerebral artery), the supraclinoid carotid artery, the vertebrobasilar vessels, the cavernous sinus region or the major dural venous sinuses.[20,21] Peripheral branches of the middle cerebral artery followed by the anterior cerebral artery are more vulnerable in craniocerebral penetrating injury than the internal carotid artery.[21,28] The development of otherwise unexplained subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) or delayed hematoma could also suggest the presence of a vascular injury, and thus warrant angiography.[20,29]

INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE MONITORING

The concept and management of Intracranial pressure (ICP) is based on Monro–Kellie doctrine.[30] According to this doctrine, since the total skull volume is a constant entity, ICP is dependent on the volume of cranial contents. Under physiological conditions, these contents are brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and vasculature (blood volume).[31] Even small increments in volume can lead to larger increases in ICP because of the rigidity of the skull. Following trauma, there may be mass lesions that need to be incorporated into this equation. Brain volume may increase because of edema (predominantly cytotoxic after trauma).[31] Vascular volume can increase if venous outflow is blocked or if there is an increased cerebral blood flow (CBF) because of seizures, pyrexia, or loss of autoregulation.[31] CSF volume may increase because of blockade of outflow tracts or hindrance with reabsorption.[31]

ICP monitoring has been well documented to be an important predictor of prognosis in severe nonpenetrating traumatic brain injury (TBI) as intracranial hypertension (ICH) is clearly associated with worse recovery and optimum control of elevated ICP leads to a better outcome.[12,13] However, very little clinical data are available on the indications and applications of ICP monitoring in PBI patients.[1] The only published studies on the role of ICP monitoring in PBI are from military settings, and there is a lack of literature from centers attending civilian PBI patients. Nonetheless, the available data suggest a higher frequency of raised ICP in PBI patients,[1,25,32–34] and when present, raised ICP is documented to be a predictor of worse prognosis.[26,35] Nagib et al. reported in their series of 13 patients with PBI that outcome was superior in those who never manifested ICH.[26] Crockard recorded ICP in 20 patients very early after PBI and found a very high mortality associated with elevated ICP, and a much better outcome in those in whom ICH never manifested.[32]

Unfortunately, in comparison with the Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury, there is little clinical evidence to evaluate the beneficial effect of management of ICP on outcomes of patients with PBI.[1,36] However, because of this short coming, general guidelines for ICP management in nonpenetrating TBI have been applied to PBI patients as well. In cases, where ICP is monitored and ICH is present, treatment measures are the same, which are used in nonpenetrating TBI, i.e. hyperventilation, mannitol, CSF drainage, high-dose barbiturates, and more recently, decompressive craniectomy.[1,36]

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF PBI

Treatment of small entrance bullet wounds to the head with local wound care and closure in patients whose scalp is not devitalized and have no significant intracranial pathologic findings is recommended in the Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury.[37] More extensive wounds with nonviable scalp, bone, or dura should be debrided more extensively before primary closure or grafting to secure a watertight wound [Figure 3a – c].[37] When there is significant mass effect, necrotic brain tissue should be debrided and safely accessible bone fragments should be removed.[38] Intracranial hematomas with significant mass effect should be evacuated. Routine surgical removal of bone or missile fragments lodged distant from the entry site especially in the eloquent areas of the brain is not recommended. Although removal of these foreign bodies from eloquent cortex may decrease the risk of posttraumatic epilepsy,[39] it has been documented to correlate with worse outcomes and higher morbidity,[1,23,37,40] A conservative approach toward cerebral debridement in general has, thus, been recommended.

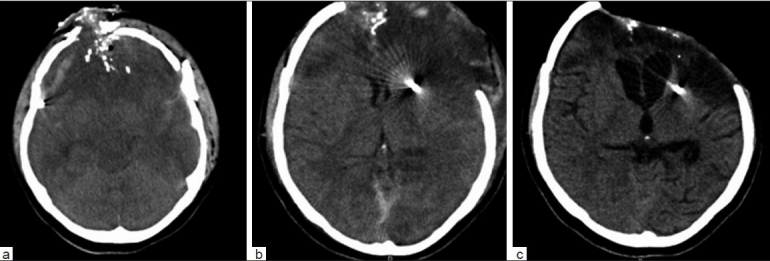

Figure 3.

(a) Axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain showing compound expansile skull fracture with multiple bone fragments along the trajectory and global cerebral edema. Basal cisterns are totally effaced. This 35 - year old patient came to us within 20 mins of gunshot injury. On examination, he had Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 3, with open herniating brain through a complex scalp defect. (b) The patient underwent decompressive craniectomy, repair of superior sagittal sinus, wound debridement, and expansile duroplasty using pericranium and temporalis fascia. Post-operative CT scan of the brain revealed swollen brain herniating through craniectomy defect. (c) Post-operative axial CT scan of the brain (2 months after surgery) showing normal appearance of ventricles and sunken scalp flap. At that time, the patient was electively admitted for cranioplasty. He was awake and alert, speaking spontaneously, following commands, and moving all four limbs

Surgical treatment should be performed within 12 h of the injury to decrease the risk of infectious complications.[24,38] Surgical incision should be done in such a fashion so as to incorporate (if possible) the area that needs debridement and vascular supply of the flap. When the trajectory of the missile violates an open air sinus, a water tight closure of the dura should be done as the literature suggests that it may decrease the risk of abscess formation and CSF fistulas.[1,37,41,42]

It is still debatable that which technique, craniotomy, or craniectomy, is best to achieve the most optimal results. No statistically significant advantage of one technique over the other has been described in reports of morbidity and mortality rates associated with the two procedures.[3,43] A recent large study of military patients suffering from severe PBI reported optimum outcomes with early decompressive craniectomy.[44] In military settings, there has been a recent paradigm shift toward an aggressive approach comprising of rapid, far forward cranial decompression with water-tight dural closure followed by rapid evacuation to a major trauma center. This approach, accompanied by subsequent aggressive critical care, has led to better outcomes in wartime PBI patients.[44] However, the wartime injuries differ considerably from the civilian PBI, and the application of military data to civilian population must be done cautiously.

VASCULAR COMPLICATIONS OF PBI

Vascular complications after PBI range from under 5%–40% in various reports.[3,45,46] Features associated with a higher risk of vascular injuries development in missile wounds include orbitofacial or pterional PBI, presence of intracranial hematoma and injuries with fragments crossing two or more dural compartments.[3,7,20,47] All such missile injuries in which large vessel damage is suspected should be explored with cerebral angiography. A four-vessel angiogram is not needed in all cases; only the pertinent ones need to be explored or a CT angiogram may be done. Angiography is also strongly recommended in the case of delayed and/or unexplained SAH or intracranial hematoma development.[3,28,46,48] The importance of angiography in the diagnosis of vascular complications lies in the bad outcome associated with this pathology when it is not aggressively treated. Sometimes vascular injuries are delayed in onset, appearing even weeks or months after the trauma, and an initial negative angiography is not conclusive. When suspicion is maintained, repeating the test 2–3 weeks after the trauma is recommended.[3,7,28,46]

The common vascular complications after PBI include traumatic intracranial aneurysms (TICAs) or arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs), SAH, and vasospasm.[47] These complications are discussed individually in the following text.

Traumatic intracranial aneurysm

Traumatic intracranial aneurysm formation is the most commonly described vascular injury after PBI.[3,7,28,46,48] Approximately 20% of traumatic aneurysms after TBI are caused by PBI.[47] Damage to an arterial wall by PBI causes a TICA. Although rare cases of partial damage to the arterial wall have been described (true TICA), traumatic intracranial aneurysms caused by PBI are mainly false aneurysms.[49–51] Cerebral angiography (CT or conventional) remains the most optimum modality to detect intracranial aneurysms.[28] Once identified, surgical or endovascular repair are the treatment options.[51]

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

The frequency of SAH in PBI patients ranges from 31% to 78%.[1,28,52,53] The presence of SAH after PBI has been documented to correlate significantly with mortality.[52] Additionally, SAH near large vascular territories and intraventricular hemorrhage may lead to poor outcomes.[54]

Vasospasm

A dreaded complication of SAH is the development of vasospasm which is caused by reactive smooth muscle contraction in the walls of the vasculature.[1,54] The subsequent decreased CBF, if severe, can lead to cerebral ischemia and infarction. However, in a study, no significant difference in outcome (3-month Glasgow outcome scale) was noted when PBI patients with/without vasospasm were compared.[55] Vasospasm may be detected by increased velocities on Doppler ultrasound. Treatment may include medical management and/or endovascular angioplasty. Medical management includes hypertension, hypervolemia, and hemodilution, i.e., the conventional HHH therapy.[56]

MANAGEMENT OF CEREBROSPINAL FLUID LEAK

Cerebrospinal fluid leakage is a common complication of PBI. Arendall and Meirowsky reported a 28% instance of CSF leaks.[57] Cerebrospinal fluid leaks after PBI have been documented to be highly predictive of infectious complications.[58] Meirowsky et al. reported in Vietnam Head Injury Study the incidence of infection as 49.5% versus 4.6% in 1032 casualties with and without CSF leaks, respectively.[59] Gonul et al. in a military series of 148 PBI patients have reported that the variable most highly correlated with intracranial infection was the presence of an acute or delayed CSF leak, which had a 63% infection rate.[41]

Cerebrospinal fluid leak develops because of the dural tear by the missile along with a failure to adequately seal the defect by normal tissue healing processes. CSF leaks can present through the entry or exit sites of the projectile as well as through the ear or nose when the mastoid air cells and the open-air sinuses have been violated, respectively.[1] The Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury recommended the surgical correction for CSF leaks which do not close spontaneously or are refractory to CSF diversion through a ventricular or lumbar drain.[58] The injury wounds associated with CSF leaks need to be extensively explored in order to allow watertight closure, either by direct closure of dural defects or by using grafting materials. Synthetic grafts can, however, by virtue of being a foreign body, become a potential source of infection, and they must be used cautiously especially in grossly contaminated wounds.[60] The management of CSF leaks remote from the point of entry or exit may involve CSF diversion. However, the risk of herniation syndromes because of mass effect and/or midline shift must be carefully evaluated before placing a lumbar drain.[1] In refractory leaks, the possibility of hydrocephalus should be explored and permanent CSF diversion considered.

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR PBI

Infectious complications are not uncommon after PBI, and they are also associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates.[61] The risk of local wound infections, meningitis, ventriculitis, or cerebral abscess are particularly high among PBI patients because of the presence of contaminated foreign objects, skin, hair, and bone fragments driven into the brain tissue along the projectile track.[1,62] Infectious complications are more frequent when cerebrospinal fluid leaks, air sinus wounds, transventricular injuries or those ones crossing the midline occur.[3,61] A higher incidence of intracranial infections after PBI is documented in studies on military PBI (4%–11%) as compared to series on civilian PBI (1%–5%).[61]

Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently associated organism. However, gram negative bacteria also frequently cause intracranial infection after PBI.[61] The administration of broad spectrum antibiotic therapy is deemed necessary in all patients with PBI based on empirical evidence from military series where the rate of infectious complications was as high as 58.8% in the preantibiotic era.[62] In a large retrospective review of civilian PBI data, the rate of infection was documented to be 1%–5% with the use of broad spectrum antibiotics.[63] Based on available literature, it is recommended that broad spectrum antibiotics should be instituted in all PBI cases, and must be started as soon as possible.

There is a considerable variation in the preference for antibiotic regimen for prophylaxis in PBI patients. Cephalosporins, however, are the most preferred antibiotics.[1,3,62,64] Esposito and Walker have recommended the use of intravenous ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and vancomycin for a minimum of 6 weeks for PBI patients.[1]

The “Infection in Neurosurgery” Working Party of British Society for Antimicrobial Therapy recommended the following regimen for PBI: intravenous co-amoxiclav 1.2g q 8h, or intravenous cefuroxime 1.5g, then 750mg q 8 h with intravenous metronidazole 500mg q 8 h (or 1g q 12h per rectum or 400mg q 8h by mouth).[65] It is recommended that this regimen should be started as soon as possible after injury and continued for 5 days postoperatively. Based on the available literature, we recommend that antibiotic prophylaxis must be maintained for at least 7–14 days.

ANTISEIZURE PROPHYLAXIS FOR PBI

The risk of posttraumatic epilepsy after PBI is high probably due to direct traumatic injury to the cerebral cortex with subsequent cerebral scarring. It is reported that the more severe the injury to the brain according to the Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) grade, the higher the risk for the development of posttraumatic epilepsy.[1,66,67] About 30%–50% of patients suffering a PBI will develop seizures.[67] It is estimated that up to 10% of them will appear early (first 7 days after the trauma), and 80% during the first 2 years, but about 18% may not have their first seizure until 5 or more years after injury.[39,68] Although the initial studies did not confirm the beneficial effect of the prophylactic anticonvulsants administration, more recent ones recommend the prophylactic anticonvulsants use (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate, or phenobarbital) in the first week after an injury[66,67] . It is acceptable not to use prophylactic anticonvulsants at all in case of smaller, less serious trauma. Besides, the use of anticonvulsants beyond the first 7 days of injury is generally not recommended.[66,67]

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS IN PBI

Age

Increasing age is correlated with a worse prognosis in PBI.[1,2] Age greater than 50 is documented to be associated with an increased mortality in PBI patients.[2]

Suicide attempt

Suicide attempt is correlated with a higher mortality in PBI when compared to other causes.[2] Suicide is an important cause of PBI in civilian population whereas military PBI is commonly associated with shell and shrapnel wounds. Suicide carries a worse prognosis probably because of close range injury.

Mode of injury

PBIs are differentiated into the following types based on mode of injury: penetrating (a foreign object penetrates skull and dura and remains lodged within the intracranial cavity); tangential (a foreign object glances off the skull, often driving bone fragments into the brain); and perforating (a ‘through-and through’ injury, characterized by entry and exit wounds).[2] Out of these three, perforating brain injuries are associated with a worse outcome.

Hypotension

Hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg) is correlated with high mortality in PBI patients.[53] Hypotension comprises an important complication of traumatic brain injury. The incidence of hypotension in PBI patients varies from 10% to 50%.[2]

Coagulopathy

Coagulopathy in PBI patients is associated with high mortality, however, the evidence is not sufficient.[69] Coagulation studies available include prothrombin time, thrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, fibrin degradation products, and platelet count.[2]

Respiratory distress

Respiratory distress in PBI patients is associated with worse prognosis.[70] Although a consistent definition is lacking, respiratory distress in PBI patients is defined as a respiratory rate of less than 10, apnea, or respiratory depression.[2]

Glasgow coma scale

Low GCS is associated with an unfavorable outcome in both civilian and military PBI.[2] In nonpenetrating TBI, patients with a GCS score <8 are described as having severe injuries, and patients with GCS scores of 9–12 are classified as moderate. In PBI patients, large proportions of civilian patients are admitted with a GCS score of 3–5. However, in military series, patients have a better GCS score, ranging from 13 to 15.[2]

Pupillary size and light reflex

Bilaterally fixed and dilated pupils are highly predictive of mortality in PBI patients.[69] An abnormal pupillary light reflex may be an indirect indicator of cerebral herniation or possible brain stem injury. Measurement of pupillary reactivity includes measurement of the light reflex and size of the pupils.[2]

Intracranial pressure

Raised ICP is predictive of high mortality.[26,35] Brain trauma, whether closed or penetrating, leads to increased ICP. The limited literature available on ICP monitoring in PBI patients suggests that a raised ICP during initial 72 h of injury carries worse prognosis.[2]

CT scan findings

Several CT scan findings have been documented to be associated with worse outcome. These include bihemispheric lesions, multilobar injuries, intraventricular hemorrhage, uncal herniation, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.[1,2]

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The management of PBI differs considerably from nonpenetrating brain injury because of the unique mechanism of injury and pathophysiology involved in this type of trauma. The introduction of Guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brain Injury has revolutionized the medical and surgical management of PBI during the last decade. There has been a paradigm shift toward a less aggressive debridement of deep seated fragments and a more aggressive antibiotic prophylaxis in an effort to improve outcomes. However, there is still a need for large scale multicenter randomized controlled trials to evaluate the current guidelines. Research in this area is highly warranted as PBI patients still present a significant challenge to practicing neurosurgeons worldwide.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Esposito DP, Walker JP. Contemporary management of penetrating brain injury. Neurosurg Q. 2009;19:249–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Part 2. Prognosis in penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S44–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutiérrez-González R, Boto GR, Rivero-Garvía M, Pérez-Zamarrón A, Gómez G. Penetrating brain injury by drill bit. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalil N, Elwany MN, Miller JD. Transcranial stab wounds: Morbidity and medicolegal awareness. Surg Neurol. 1991;35:294–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(91)90008-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad FS, Manktelow AR, Brown MR, Hope PG. Penetrating head injuries: A trap for the unwary. Injury. 1996;27:72–3. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chibbaro S, Tacconi L. Orbito-cranial injuries caused by penetrating non-missile foreign bodies.Experience with eighteen patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:937–41. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-0794-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.du Trevou MD, van Dellen JR. Penetrating stabwounds to the brain: The timing of angiography in patients presenting with the weapon already removed. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:905–11. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costantinides F. A fatal case of accidental cerebral injury due to power drill. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1982;3:241–3. doi: 10.1097/00000433-198209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly AJ, Pople I, Cummins BH. Unusual craniocerebral penetrating injury by a power drill: Case report. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:471–2. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarro-Celma JA, Mir Marin MA, Aso Escario J, Castellano Arroyo M. A report of a suicide by means of an electric drill. Acta Med Leg Soc (Liege) 1989;39:247–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmeling A, Lignitz E, Strauch H. Case reports of suicide with an electric drill. Arch Kriminol. 2003;211:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullock R, Chesnut RM, Clifton G, Ghajar J, Marion DW, Narayan RK, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe head injury.Brain Trauma Foundation. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13:641–734. doi: 10.1097/00063110-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bullock R, Chestnut RM, Clifton G. Guidelines for the management of severe head injury-3rd edition. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:S1–106. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Part 1: Guidelines for the management of penetrating brain injury. Introduction and methodology. J Trauma. 2001;51:S1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barach E, Tomlanovich M, Nowak R. A pathophysiologic examination of the wounding mechanisms of firearms: Part 1. J Trauma. 1986;26:225–35. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey ME. Experimental missile wounding of the brain. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995;6:629–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ordog GJ, Wasserberger J, Balasubramanium S. Wound ballistics: Theory and practice. Am Emerg Med. 1984;13:1113–22. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blissitt PA. Care of the critically ill patient with penetrating head injury. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;18:321–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckstein M. The pre-hospital and emergency department management of penetrating wound injuries. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1995;6:741–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neuroimaging in the management of penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Offiah C, Twigg S. Imaging assessment of penetrating craniocerebral and spinal trauma. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:1146–57. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarabi B. Comparative study of bacteriological contamination between primary and secondary exploration of missile head wounds. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:610–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhri KA, Choudhury AR, al Moutaery KR, Cybulski GR. Penetrating craniocerebral shrapnel injuries during “Operation Desert Storm”: Early results of a conservative surgical treatment. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994;126:120–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01476420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helling TS, McNabney WK, Whittaker CK, Schultz CC, Watkins M. The role of early surgical intervention in civilian gunshot wounds to the head. J Trauma. 1992;32:398–400. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levi L, Borovich B, Guilburd JN, Grushkiewicz I, Lemberger A, Linn S, et al. Wartime neurosurgical experience in Lebanon, 1982-85, I: Penetrating craniocerebral injuries. Isr J Med Sci. 1990;26:548–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagib MG, Rockswold GL, Sherman RS, Lagaard MW. Civilian gunshot wounds to the brain: Prognosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:533–7. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green BF, Kraft SP, Carter KD, Buncic JR, Nerad JA, Armstrong D. Intraorbital wood.Detection by magnetic resonance imaging. Opthalmology. 1990;97:608–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vascular complications of penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S26–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy ML, Rezai A, Masri LS, Litofsky SN, Giannotta SL, Apuzzo ML, et al. The significance of subarachnoid hemorrhage after penetrating craniocerebral injury: Correlations with angiography and outcome in a civilian population. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:532–40. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: Applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology. 2001;56:1746–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chesnut RM. Care of central nervous system injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:119–56. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crockard HA. Early intracranial pressure studies in gunshot wounds of the brain. J Trauma. 1975;15:339–47. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197504000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lillard PL. Five years experience with penetrating craniocerebral gunshot wounds. Surg Neurol. 1978;9:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarnaik AP, Kopec J, Moylan P, Alvarez D, Canady A. Role of aggressive intracranial ressure control in management of pediatric craniocerebral gunshot wounds with unfavorable features. J Trauma. 1989;29:1434–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198910000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miner ME, Ewing-Cobbs L, Kopaniky DR, Cabrera J, Kaufmann P. The results of treatment of gunshot wounds to the brain in children. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:20–5. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Intracranial pressure monitoring in the management of penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Surgical management of penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubschmann O, Shapiro K, Baden M, Shulman K. Craniocerebral gunshot injuries in civilian practice: Prognostic criteria and surgical management experience with 82 cases. J Trauma. 1979;19:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salazar AM, Jabbari B, Vance SC, Grafman J, Amin D, Dillon JD. Epilepsy after penetrating head injury, I.Clinical correlates: A report of the Vietnam Head Injury Study. Neurology. 1985;35:1406–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.10.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammon WM. Analysis of 2187 consecutive penetrating wounds of the brain from Vietnam. J Neurosurg. 1971;34:127–31. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.34.2part1.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gönül E, Baysefer A, Kahraman S, Ciklatekerlioðlu O, Gezen F, Yayla O, et al. Causes of infections and management results in penetrating craniocerebral injuries. Neurosurg Rev. 1997;20:177–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01105561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aarabi B, Taghipour M, Alibaii E, Kamgarpour A. Central nervous system infections after military missile head wounds. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:500–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199803000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rish BL, Dillon D, Caveness WF, Mohr JP, Kistler P, Weiss GH. Evolution of craniotomy as a debridement technique for penetrating craniocerebral injuries. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:772–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.6.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bell RS, Mossop CM, Dirks MS, Stephens FL, Mulligan L, Ecker R, et al. Early decompressive craniectomy for severe penetrating and closed head injury during wartime. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E1. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.FOCUS1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nathoo N, Boodhoo H, Nadvi SS, Naidoo SR, Gouws E. Transcranial brainstem stab injuries: A retrospective analysis of 17 patients. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1117–22. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy ML, Rezai A, Masri LS, Litofsky SN, Giannotta SL, Apuzzo ML, et al. The significance of subarachnoid hemorrhage after penetrating craniocerebral injury: Correlations with angiography and outcome in a civilian population. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:532–40. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao GP, Rao NS, Reddy PK. Technique of removal of an impacted sharp object in a penetrating head injury using the lever principle. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:569–71. doi: 10.1080/02688699844457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kieck CF, de Villiers JC. Vascular lesions due to transcranial stab wounds. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:42–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.1.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aarabi B. Traumatic aneurysms of brain due to high velocity missile head wounds. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:1056–63. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198806010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aarabi B. Management of traumatic aneurysms caused by high velocity missile headwounds. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995;6:775–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haddad FS, Haddad GF, Taha J. Traumatic intracranial aneurysms caused by missiles: Their presentation and management. Neurosurgery. 1997;28:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaufman HH, Makela ME, Lee KF, Haid RW, Jr, Gildenberg PL. Gunshot wounds to the head: A perspective. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:689–95. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aldrich EF, Eisenberg HM, Saydjari C, Foulkes MA, Jane JA, Marshall LF, et al. Predictors of mortality in severely head- injured patients with civilian gunshot wounds: A report from the NIH Traumatic Coma Data Bank. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:418–23. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90109-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimura T, Mukai T, Teramoto A, Toda S, Yamamoto Y, Nakamura T, et al. Clinicopathological studies of craniocerebral gunshot wound injuries. No Shinkei Geka. 1997;25:607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kordestani RK, Counelis GJ, McBride DQ, Martin NA. Cerebral arterial spasm after penetrating craniocerebral gunshot wounds: Transcranial Doppler and cerebral blood flow findings. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:351–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199708000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muench E, Horn P, Bauhuf C, Roth H, Philipps M, Hermann P, et al. Effects of hypervolemia and hypertension on regional cerebral blood flow, intracranial pressure, and brain tissue oxygenation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1844–51. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275392.08410.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arendall RE, Meinowsky AM. Air sinus wounds: An analysis of 163 consecutive cases incurred in the Korean War, 1950-1952. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:377–80. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198310000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. J Trauma. 2001;51:S29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meirowsky AM, Caveness WF, Dillon JD, Rish BL, Mohr JP, Kistler JP, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid fistulas complicating missile wounds of the brain. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:44–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.1.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vrankoviæ D, Heæimoviæ I, Splavski B, Dmitroviæ B. Management of missile wounds of the cerebral dura mater: Experience with 69 cases. Neurochirurgia. 1992;35:150–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Antibiotic prophylaxis for penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitaker R. Gunshot wounds of the cranium: With special reference to those of the brain. Br J Surg. 1916;3:708–35. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benzel EC, Day WT, Kesterson L, Willis BK, Kessler CW, Modling D, et al. Civilian craniocerebral gunshot wounds. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:67–71. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaufman HH, Schwab K, Salazar AM. A national survey of neurosurgical care for penetrating head injury. Surg Neurol. 1991;36:370–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(91)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bayston R, de Louvois J, Brown EM, Johnston RA, Lees P, Pople IK. Use of antibiotics in penetrating craniocerebral injuries. “Infection in Neurosurgery” Working Party of British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Lancet. 2000;355:1813–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aarabi B, Taghipour M, Haghnegahdar A, Farokhi MR, Mobley L. Prognostic factors in the occurrence of posttraumatic epilepsy after penetrating head injury suffered during military service. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;8:e1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.8.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Antiseizure prophylaxis for penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S41–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caveness WF, Meirowsky AM, Rish BL, Mohr JP, Kistler JP, Dillon JD, et al. The nature of posttraumatic epilepsy. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:545–53. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.5.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaffrey ME, Polin RS, Phillips CD, Germanson T, Shaffrey CI, Jane JA. Classification of civilian craniocerebral gunshot wounds: A multivariate analysis predictive of mortality. J Neurotrauma. 1992;9:S279–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobs DG, Brandt CP, Piotrowski JJ, McHenry CR. Transcranial gunshot wounds: Cost and consequences. Am Surg. 1995;61:647–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]