Abstract

The key to successful elimination of tuberculosis (TB) is treatment of cases with optimum chemotherapy. Poor chemotherapy over time has led to drug-resistant disease. Drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis develops by the selective growth of resistant mutants. The incidence of drug-resistant cases depends on the number of bacilli and the drug-resistant mutants in the lesion. The latter is low for individual drugs and even lower for two and three drugs. Therefore, use of combination chemotherapy with three or more drugs results in cure. However, irregular treatment, inadequate drugs, inadequate drug doses or addition of a single drug to a failing regimen allows selective growth of resistant mutants and acquired drug-resistant TB. Contacts of these resistant cases develop primary drug resistant TB. Thus, drug resistance in tuberculosis is a “man-made problem”. Anti-TB chemotherapy must be given optimally by (i) ensuring adequate absorption of drugs, (ii) timely diagnosis and management of drug toxicities and (iii) treatment adherence. New classes of anti-TB drugs are needed; but are unlikely to become available soon. It is vital that the 21st century physicians understand the basic principles of TB chemotherapy to ensure efficient use of available drugs to postpone or even reverse epidemics drug-resistant TB.

Keywords: Extremely drug-resistant (XXDR) TB, extensive drug (XDR) resistant, first-line drugs, multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB, second-line drugs, total drug-resistant (TDR) TB

INTRODUCTION

Failure to eliminate tuberculosis (TB) that is 100% preventable and 100% curable is mankind's worst ongoing blunder.[1] The key to successful elimination of TB is optimum treatment of cases. We have always known that erratic drug supplies and failure of patients to complete treatment lead to even more dangerous forms of TB i.e. drug-resistant disease. Equally important are prescription practices and failure to ensure treatment adherence by the treating physicians. Standard diagnostic and treatment protocols are available using highly effective drugs[2–9] based on sound scientific principles and years of research. However, neglect of these basic principles by large sections of the medical community has contributed to emergence of drug-resistance.

Drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis develops by the selective growth of resistant mutants.[10] The incidence of drug-resistant cases depends on the number of bacilli and the probability of drug-resistant mutants in the lesion. The latter is as low as 10-3–10-8for individual drugs, 10-12–10-14for two drugs and 10-18–10-20for three drugs.[11,12] When three or more drugs are utilized together for treatment of TB, the chances of acquiring drug resistance is negligible.[11,13] Poor chemotherapy however, in the form of inadequate drugs, inadequate drug doses or addition of a single drug to a failing regimen (addition syndrome) results in selective growth of the drug-resistant mutants and consequently acquired drug-resistant TB. Contacts of these resistant cases develop primary drug-resistant TB.[14] Thus, drug resistance in tuberculosis is a “man-made problem”, acquired resistance, a mark of a poor treatment practices in the current time and primary resistance an indicator of treatment practices in the past.[15]

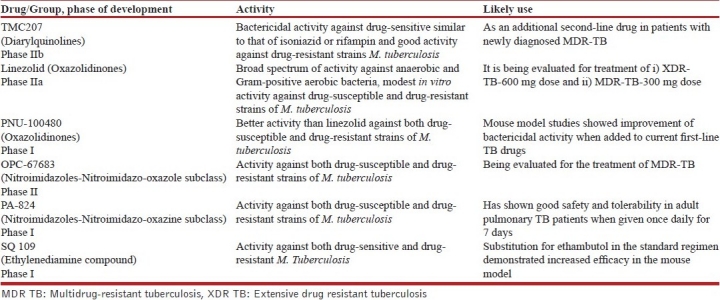

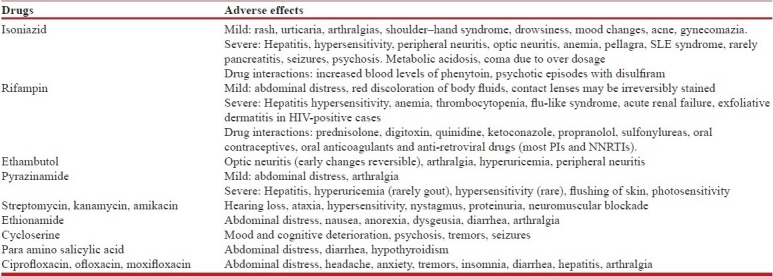

Good treatment is a pre-requisite to the prevention of emergence of resistance. The outcome of “careless care”[16] over time has resulted in emergence of progressive resistance to the anti-TB drugs. Resistance to the main first-line drugs isoniazid and rifampin multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB)[17] was followed by recognition of additional resistance to injectable second-line drugs (kanamycin, amikacin, capreomycin) plus a fluoroquinolone-extensive drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB).[18] “Extremely” drug-resistant (XXDR TB) or total drug-resistant TB (TDR) have now been proposed for cases resistant to all available first- and second-line drugs.[19–21] Although several new agents that may be used as “third-line drugs” are in the preclinical stage of development; presently there are only six drugs with potential activity against TB in the clinical pipeline [Table 1].[22] It is vital that the 21st century physicians understand the basic principles of TB chemotherapy to ensure efficient use of available drugs to postpone or even reverse epidemics of drug-resistant TB.[23]

Table 1.

Newer anti-TB drugs in clinical development

MANAGEMENT OF TB

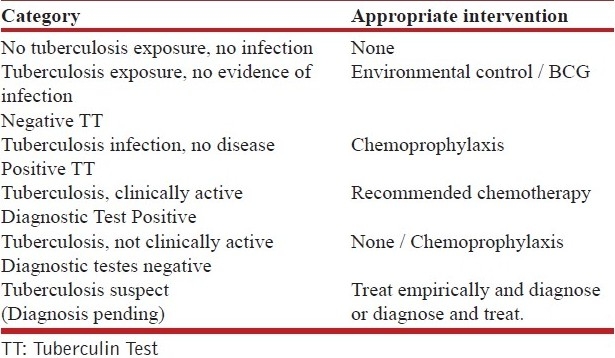

The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have classified persons, exposed to and /or infected with M. tuberculosis. The classification[4] is based on the broad host–parasite relationship as described by exposure history, infection and disease. The suggested intervention required in each of the categories is shown in Table 2. This classification helps us to understand the natural history of TB infection in man and the rationale for intervention required at each stage

Table 2.

The american thoracic society and centers for disease control based categories of persons exposed to and/or infected with M. tuberculosis[4] and appropriate intervention for each category

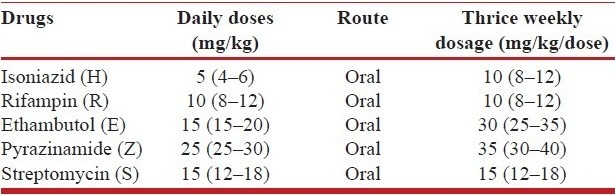

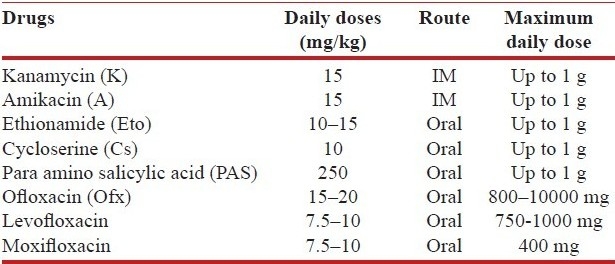

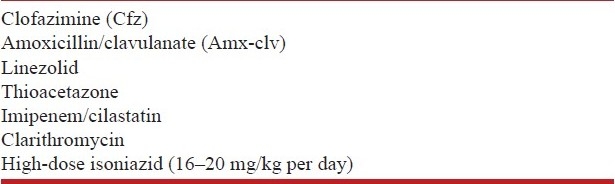

THE ANTI-TUBERCULOSIS DRUGS

Isoniazid (H), rifampin (R), ethambutol (E), pyrazinamide(Z) and streptomycin (S) are the essential first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs.[6] Aminoglycosides (kanamycin, amikacin), quinolones (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin), ethionamide or prothionamide, cycloserine, para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) and polypeptide (capreomycin) are the second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs.[22] The recommended doses of the anti-tuberculosis drugs and their adverse effects[5–9,24–30] are as shown in Tables 3a, b and 4. Table 5 shows drugs which may be used as salvage therapy for XDR TB.[29,30]

Table 3a.

WHO recommended doses of the first-line antituberculosis drugs

Table 3b.

Recommended doses of second-line anti-TB drugs

Table 4.

Adverse effects of the anti-tuberculosis drugs

Table 5.

Other drugs of uncertain efficacy used in treatment of DR-TB[20]

PRINCIPLES OF ANTI-TUBERCULOSIS CHEMOTHERAPY

The anti-tuberculosis therapy is a unique, two-phased chemotherapy consisting of initial intensive phase with multiple drugs (three or more) and continuation phase with two or three drugs. The multidrug initial intensive phase is given to take care of the drug-resistant organisms and to achieve ‘a quick kill’ to reduce the bacillary load, which in turn reduces the number of “persisters’ in the lesions. “Persisters” are drug-sensitive organisms, which become dormant and are later responsible for relapses. The continuation phase of chemotherapy, consisting of two drugs is therefore given to kill the “persisters,” which show intermittent activity.[2,3]

The role of individual drugs in first-line chemotherapy of TB[31] is unique. Isoniazid is responsible for the initial kill of about 95% organisms during the first two days of treatment. Its bactericidal role is then replaced by rifampicin and pyrazinamide during the intensive phase. In the continuation phase, rifampin is the most effective drug against dormant bacilli (persisters), as shown by the similarity of response by patients with initially isoniazid-resistant or sensitive strains. When either rifampin or isoniazid is not used, the duration of chemotherapy is 12 to 18 months. When both isoniazid and rifampin are used in treatment, the optimum duration of chemotherapy is 9 months. Addition of pyrazinamide, but not neither streptomycin nor ethambutol reduces the duration to six months. Prolongation of chemotherapy beyond these periods increases the risk of toxicity while providing no additional benefit. Second-line therapy duration ranges from 18 to 24 months.

TREATMENT GUIDELINES: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

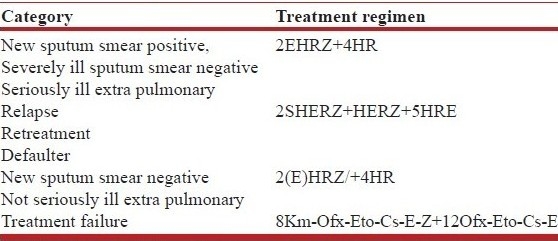

Public health programs in many countries follow guidelines for treatment of TB developed by the World Health Organization (WHO).[6–9,27–29] These guidelines were practiced till 2009 in which the treatment regimes were categorized into four categories [Table 6a]. Categories 1–3 used a combination of first-line drugs for the shortest acceptable period. Category 1 is for treatment of new cases (an initial intensive phase (IIP) of four drugs ethambutol, isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide for 2 months and 4 months of continuation phase (CP) of two drugs isoniazid and rifampicin -2EHRZ/4HR). Category 2 is “retreatment” regimen (8 months of isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, with pyrazinamide, and streptomycin added for the first 2 months—2SHRZE/1HRZE/5HRE) was recommended for relapse and retreatment cases. Category 3 recommended omission of ethambutol for children, patients, with smear-negative pulmonary or extra-pulmonary TB that is fully drug-susceptible and patients negative for Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Category 4 was for treatment of drug-resistant TB using a standard treatment regimen (STR) using combination of second-line drugs; the initial phase five drugs, pyrazinamide (Z), kanamycin (Km), ofloxacin (Ofx), ethionamide (Eto) and cycloserine (CS) for 6-8 months and the continuation phase of three drugs, ofloxacin (Ofx), ethionamide (Eto) and cycloserine (CS) for 12 months. For treatment of XDR-TB, salvage chemotherapy may be considered[29,30] using capreomycin (Cm), moxifloxacin (Mfx), para amino salicylic acid (PAS) +/- cycloserine (Cs) and two or three of additional agents from Table 5.

Table 6a.

Previous World Health Organization (WHO) treatment categories

The category 1 treatment regimen was recommended based on the results of randomized trials. This regimen was found to have good bactericidal property (infectious patients quickly become non-infectious and sputum conversion occurs at two months in more than 90% cases) and good sterilizing property (low relapse rates of 0–2%), is equally efficacious in primary isoniazid resistant cases and has high cure rates even after premature discontinuation. Further it was found suitable for adults and children, for pregnant and lactating women, for cases associated with diabetes mellitus (DM) and HIV infection, for cases with pre-existing liver diseases (but normal liver functions) and mild renal failure.[3] Unlike the category 1, the category 2 retreatment regimen was a product of expert opinion.[32] It was originally designed for resource-poor settings with low prevalence of initial drug resistance, and for patients previously treated with a regimen that used rifampin only for the first two months of therapy.[27] However, this regimen was increasingly criticized[33] because of poor results, particularly in settings where rifampin was used throughout initial therapy or prevalence of initial drug resistance was high.[34,35] When used after failure of category 1 treatment, this regimen effectively allowed addition of SM, addition of one drug to a failing regimen, which was against the basic principle of TB chemotherapy. Similarly, in category 3 ethambutol omission was recommended based on the assumption that lesions in some cases like those negative for HIV, smear-negative pulmonary or extra-pulmonary TB harbour fewer bacilli and hence have little risk of selecting resistant bacilli. However, as initial resistance to isoniazid Is common in many areas; a revised guideline in 2004[36] recommended that ethambutol be included as a fourth drug during the initial phase of treatment even for smear-negative pulmonary or extra-pulmonary TB patients and effectively eliminated category 3.

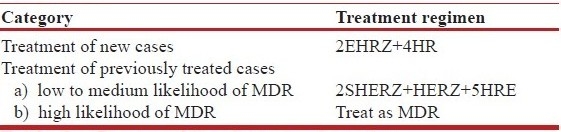

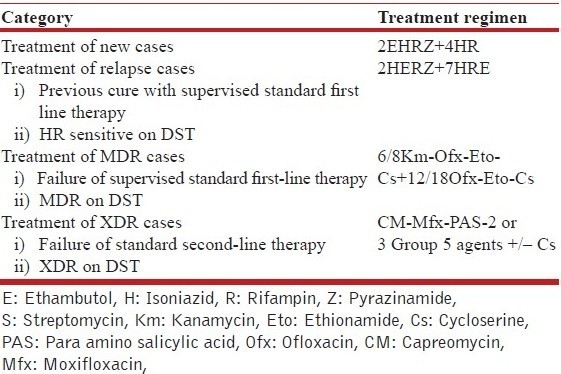

These treatment categories were not only controversial but also created confusion for the treating physician. Therefore the WHO guidelines were revised and updated in 2009 [Table 6b].[37] It remains to be seen if the revised guidelines address deficiencies of the previous guidelines.[38] However, the recommendation to start empiric second-line therapy in previously treated cases with high likelihood of MDR may result in hasty and casual initiation of second-line therapy and create further drug resistance resulting in XDR/XXDR/TDR. It would be reasonable to allocate treatment groups into more definitive categories [Table 6c]. While standard 2EHRZ/4HR should be used for all new cases, in cases where retreatment is required for relapse after first-line therapy, it is prudent to start first-line therapy and order drug susceptibility testing (DST). If DST is not available and the patient shows good response in 2–3 months or DST shows drug-sensitive disease, CP may be commenced and given for 7 months.[3] Cases that show failure of fully supervised first-line therapy or show MDR-TB on DST should be treated with second-line drugs. Cases failed on MDR treatment or showing XDR on DST may be treated with salvage regimens.

Table 6b.

World health organization (WHO) treatment categories[37]

Table 6c.

Proposed treatment categories

CHEMOTHERAPY OF TB IN SPECIAL SITUATIONS[37,39–43]

Pregnancy

Rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide can be used safely during pregnancy. Streptomycin is not given as it can cause ototoxicity to the fetus. Addition of pyridoxine in the dose of 10 mg/day is recommended to prevent isoniazid peripheral neuropathy.

Diabetes mellitus

Standard recommended chemotherapy must be used. Tight glycemic control is desirable. Doses of oral hypoglycemic agents may have to be increased due to drug interaction with rifampin. Prophylactic pyridoxine in the dose of 10 mg/day is recommended to prevent isoniazid peripheral neuropathy.

Renal failure

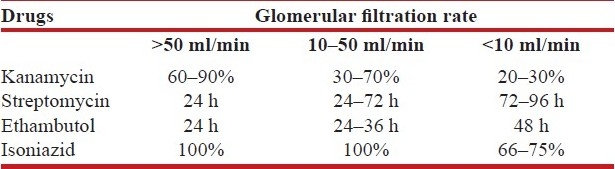

Dosages may have to be adjusted according to the creatinine clearance especially for streptomycin, ethambutol and isoniazid. In acute renal failure, ethambutol should be given 8 hours before hemodialysis. Creatinine clearance should be estimated for adjustment of some of the antituberculosis drugs. The formula, creatinine clearance = (140 - Age) Weight / 72 × serum creatinine, gives a rough estimate of the glomerular filtration rate. According to the creatinine clearance, either the dosage interval is changed or the dose is reduced as a percentage of the normal daily dose [Table 7].

Table 7.

Dose adjustment based on glomerular filtration rate

Post transplant patients and other special situations

Rifampin-containing regimens are avoided as rifampin causes increased clearance of cyclosporin.

Pre-existing liver disease

In stable disease with normal liver enzymes, all anti-tuberculous drugs may be used but frequent monitoring of liver function tests is required.

Treatment in unconscious patient/patients unable to swallow

If patients are fed by nasogastric tube or gastrostomy tube, usual doses and drugs may be powdered and administered avoiding feeds 2–3 hours before and after the dose. In cases where enterostomy has been performed or parenteral nutrition is being used, intramuscular streptomycin and intravenous quinolones may be used and switch to oral therapy once oral feed resume.

TB with HIV co-infection

In early stages, the presentations of TB in TB-HIV co-infection is the same as HIV negative but in late stages extra-pulmonary and dissemination are common. Diagnostic problems arise as other respiratory diseases occur frequently and tuberculin test may be negative. The usual short course chemotherapy as per treatment categories is indicated in HIV-positive patients. The response is usually good but relapse is more frequent.

Seriously Ill Patients with Suspected TB

Use of specific empiric anti-tuberculosis therapy (SEATT)[44] with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide can be used as a method for rapid presumptive diagnosis and treatment of febrile patients with clinical and radiological suspicion of TB, who are seriously ill and where no bacteriological or histological proof is available. Fever is used as guide for response to therapy. Rifampicin and aminoglycosides or quinolones are not used, to ensure that defervescence of fever is due to action of specific anti-TB drugs i.e. isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. Rifampicin may be added as soon as the patient is afebrile.

FOLLOW-UP AND EXPECTED RESPONSE TO ANTI-TB THERAPY

The role of chemotherapy is limited to sterilizing the lesion by killing maximum number of TB bacilli. Evaluation of anti-TB therapy should ideally be bacteriological for example. by appropriate smear and culture in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB. Standard prescribed regimens should be used if follow-up bacteriological evaluation cannot be performed in extra-pulmonary TB. Fever, accurately documented may be used as a guide for response to chemotherapy initially. However, it must be remembered that occasionally fever may take up to several weeks to subside after starting ATT.[45] There may also be secondary rise of fever after initial defervescence particularly in cases of military TB and requires treatment with corticosteroids.[46] Tuberculosis, like leprosy has a spectrum of the disease from reactive type to unreactive type, Lenzini[47] described the spectral concept based on immunology, RR (Reactive) with nodular opacities, RI (reactive intermediate) with nodular opacities and cavitation, UI (unreactive intermediate) with diffuse fibrocavitary lesion and UU (unreactive) with disseminated disease. These stages occur with progressive fall in cell mediated immunity. The differences in immune response result in differences in tissue damage and repair and residual lesions. Hence success of chemotherapy must not be judged by radiology. In fact paradoxical worsening of lesions may occur during successful TB treatment. This phenomenon is called “paradoxical response (PR)” or “immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS)” and is well known with or without HIV co-infection.[48] In TB lymphadenopathy, appearance of new nodes, enlargement of existing nodes, cold abscess formation and sinus formation can occur while on effective chemotherapy. Ten percent of cases may be left with residual nodes at the end of chemotherapy.[49] Similarly, TB meningitis may be complicated by hydrocephalus, tuberculomas and abscess formation that cause clinical deterioration despite effective ATT[50] Tuberculomas may enlarge during chemotherapy probably due to an immunological mechanism.[51] Further, several complications like bronchopleural fistula,[52] empyema and hemoptysis may occur during or after therapy and cause apparent clinical or radiological worsening. Anti-TB chemotherapy cannot prevent or cure persistent residual lesions, paradoxical worsening and complications, which are either immunologically mediated or due to mechanical complications of the disease. Steroids[53] or surgery[54] may be required as appropriate and ATT should not be modified or prolonged.

OPTIMIZING TO ANTI-TB THERAPY

Once prescribed, anti-TB chemotherapy must be given optimally by (i) ensuring adequate absorption of drugs, (ii) timely diagnosis and management of drug toxicities and (iii) treatment adherence.

ENSURING ADEQUATE ABSORPTION OF ANTI-TB THERAPY

Administration of drugs in divided doses, rifampicin after meals and concomitant administration of antacids and prokinetic drugs affect the outcome of therapy. All anti-tuberculosis drugs should be administered preferably in single daily doses to achieve peak serum levels.[55] The greater the ratio between peak serum levels and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the drug, the greater is the drug's bactericidal action. The pharmacokinetics of rifampin and isoniazid are influenced by meals,[56] and 50% of the patients are at risk of having sub-optimal concentration if rifampin is taken with food.[57] Carbohydrates and proteins seem to have virtually no influence, but a fatty meal reduces serum concentrations considerably.[58] Prokinetic drugs and antacids containing aluminum and magnesium reduce the absorption of rifampicin.[59] As anti-TB drugs are preferably administered in fixed dose combinations, ATT must be given on empty stomach followed by meals 1-2 hours after drug intake to ensure absorption.

MANAGING DRUG TOXICITY TO ANTI-TB THERAPY[43]

Gastrointestinal intolerance

Nausea due to gastrointestinal intolerance is usually self-limiting. However if symptoms persist or are intolerable, the patient may be advised to take drugs 2 hours after breakfast or at bedtime, 2–3 hours after dinner, which may help the patient to “sleep off” the side effects. Treatment with H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors may be prescribed in severe cases as they do not affect absorption of ATT unlike prokinetics.

Itching and skin rash

Itching or rash with ATT is a minor side effect provided it is not accompanied with fever or symptoms of hepatitis. In these cases, reassurance, treatment with antihistamines and application of calamine lotion allows ATT to be continued uninterrupted.

Drug hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity reactions can occur with practically all anti-tuberculous drugs. It may present with fever, joint pains, skin reactions, hepatitis, lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. A new fever or increase in fever after starting ATT indicates hypersensitivity. All ATT must be discontinued immediately and if fever subsides within 24 hours, drug hypersensitivity is confirmed. Re-introduction can be attempted with one drug at a time with careful clinical monitoring after initial symptoms subside. If one drug is identified as the causative agent, it may be omitted and a modified regimen should be given.

Hepatotoxicity

Hepatotoxicity with ATT is of three distinct types (i) an asymptomatic increase (up to four-fold elevation) of liver enzymes occur frequently but the enzyme levels revert back to normal despite continuation of chemotherapy; (ii) dose-related derangement in liver function tests may occur frequently if therapy is not given in the recommended doses adjusted for body weight; (iii) idiosyncratic hepatitis secondary to isoniazid and rifampin; although rare may lead to fatal hepatic failure. Drug-induced hepatitis has a clinical syndrome similar to viral hepatitis and usually occurs within 2 months but may occur even later during therapy. If viral etiology is excluded or tests for viral studies are not available, it is wise to presume an idiosyncratic reaction to isoniazid or rifampicin. When there is greater than four-fold rise in liver enzymes of elevated bilirubin, all hepatotoxic drugs must be discontinued immediately. Chemotherapy regimens containing non-hepatotoxic drugs like ethambutol, aminoglycosides and quinolones may be considered until liver functions return to normal; particularly in severe forms of TB. Reintroduction of all drugs in corrected doses is well tolerated once liver functions are normal in cases of dose-related hepatotoxicity or viral hepatitis occurring during anti-TB therapy. However, in case of idiosyncratic hepatitis, re-introduction of these drugs must not be attempted.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia has been reported most commonly with rifampicin. However, a few cases of thrombocytopenia with ethambutol have also been reported. It may present with petechiae or frank bleeding from various sites. Drop in platelet count can be documented when done within 24 hours of the drug intake. Previously it was recommended that after occurrence of thrombocytopenia, rifampicin must not be used again. However, recent reports suggest that re-administration can be attempted under clinical supervision and rifampicin may be tolerated well.

ENSURING ADHERENCE TO ANTI-TB THERAPY

Annik Rouillon, Former Executive Director of International Union Against TB and Lung Diseases (IUATLD) had observed “the person who swallows drugs regularly in the absence of encouragement and help is an abnormal one”.[59] Self-administered therapy (SAT) or directly observed treatment (DOT) are two options for giving anti-TB chemotherapy. SAT must always be prescribed using fixed dose combinations (FDC) as they make monotherapy impossible. However, SAT requires time and effort of healthcare workers involved in the treatment to ensure compliance, which is often lacking. Hence, since 1993, World Health Organization (WHO) recommends DOT as an important component of their five-point program; directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) to tackle the TB “global emergency”. Every effort is being made to optimize DOT. ‘Enhanced DOT’ uses incentives tailored to the target population within the context of DOT, for example incentive of food, housing, clothes and medical care. ‘Expanded DOT’ addresses TB/HIV and MDR and collaborates health programs and general health service such as alcohol de-addiction.[60] DOTS-Plus for treatment of MDR TB using a standardized treatment regimen (STR) is currently being implemented.[22] Direct observation of SLDs will be crucial for compliance of MDR TB therapy under DOTS-Plus. An 18–24-month therapy cannot be supervised using hard-pressed health workers at the DOTS centers and hence it was proposed to use DOT providers. Studies have now shown that family members supervising therapy is as effective[61] and may be a convenient and cost-effective alternative.

Reinforcing adherence to therapy through treatment literacy is important for the successful completion of therapy and cannot be substituted by any other intervention. The final option is to use legal action in the form of compulsory detention when an individual refuses treatment.[62] In practice this is seldom used, though some countries have employed compulsory detention in as many as 1% of cases.[63] However, “it is unethical, illegal, and bad public health policy to detain ‘noncompliant’ persons before making concerted efforts to address the numerous systemic deficiencies that make adherence to treatment virtually impossible.”[64]

CONCLUSION

Dubois and Dubois (1952), in their book “The White Plague-Tuberculosis, Man and Society”[65] cited Machiavelli: “Consumption (TB) in the commencement is easy to cure, and difficult to understand; but when it has neither been discovered in due time, nor treated upon a proper principle, it becomes easy to understand, and difficult to cure”. They also predicted that “drugs, vaccines or other options cannot solve the problem of TB as it is through gross errors in organization and individual life that the problem (of TB) has reached catastrophic levels”. New classes of anti-TB drugs are needed, but are unlikely to become available soon. Even if new drugs are available they may be rapidly “burnt” as a result of clinical and public health malpractices similar to some of the key old drugs.[19] The only option therefore is to use the existing drugs efficiently based on the knowledge of principles of TB chemotherapy.[66] As Mario Raviglione, director of WHO's Stop TB Department aptly puts it: “…if we don’t have the basics in place, then the result is drug resistance”.[67]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reichman LB. Tuberculosis elimination-what's to stop us? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toman K. Tuberculosis case finding and chemotherapy: Questions and answers. Geneva: WHO; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girling DJ, Coolet P. Anti-tuberculosis regimens of chemotherapy.Recommendations from the committee on treatment of International union against tuberculosis and lung disease. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1988;30:296–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American thoracic society diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;192:725–35. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint tuberculosis committee chemotherapy and management of tuberculosis. Thorax. 1990;45:403–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.5.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Tuberculosis Programme: Framework for effective tuberculosis control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. WHO/TB/94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treatment for Tuberculosis. Guidelines for National Programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. WHO/TB/97.220. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treatment of tuberculosis. Guidelines for National Programmes. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003; 2003. p. 313. WHO/CD5/TB. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treatment of tuberculosis: Guidelines for national programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; World Health Organization. WHO/CDS/TB/2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veen J. Drug resistant tuberculosis: Back to sanatoria, surgery and cod-liver oil? Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1073–975. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08071073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimao T. Drug resistance in tuberculosis control. Tubercle. 1987;68:5–15. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(87)90014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rastogi N, David HL. Mode of action of antituberculous drugs and mechanisms of resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:133–43. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vareldzis BP, Grossset J, de Kantor I, Crofton J, Laszlo A, Felten M. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: Laboratory issues.World Health Organization recommendations. Tuber Lung Dis. 1994;75:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambregts-van Weezenbeek CS, Veen J. Control of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76:455–9. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochi A, Vareldzis B, Styblo K. Multidrug resistant tuberculosis and its control. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:104–10. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90023-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raviglione M. XDR-TB: Entering the post-antibiotic era? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1185–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iseman MD. Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:784–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309093291108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs--worldwide, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Migliori GB, Loddenkemper R, Blasi F, Raviglione MC. 125 years after Robert Koch's discovery of the tubercle bacillus: The new XDR-TB threat. Is “science” enough to tackle the epidemic? Eur Respir J. 2007;29:423–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00001307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velayati AA, Masjedi MR, Farnia P, Tabarsi P, Ghanavi J, ZiaZarifi A. Emergence of New Forms of Totally Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Bacilli: Super Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis or Totally Drug-Resistant Strains in Iran. Chest. 2009;136:420–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schluger NW. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: What is to be done? Chest. 2009;136:333–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lienhardt C, Vernon A, Raviglione MC. New drugs and new regimens for the treatment of tuberculosis: Review of the drug development pipeline and implications for national programmes. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:186–93. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328337580c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dye C. Doomsday postponed.Preventing and reversing epidemics of drug-resistant tuberculosis? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:81–7. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davison DT. Le HL Drug treatment of tuberculosis-1992 Drugs. 1992;43:651–73. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199243050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanscoy RE, Wilkowske CJ. Antituberculosis agents. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:179–87. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iseman MD, Youngchaiyud P. Update treatment of multi drug resistant tuberculosis, proceedings of a sponsored symposium to the 29th world conference of the IUATLD/UICTMR. Suppl 2. Vol. 45. Bangkok, Thailand: Chemotherapy S; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crofton J, Chaulet P, Maher D. Guidelines for the management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. WHO/TB/96.210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emergency Update 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008; 2008. Guidelines for programmatic management of drug resistant tuberculosis; p. 402. WHO/HTM/TB. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caminero JA, Sotgiu G, Zumla A, Migliori GB. Best drug treatment for multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:621–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchison DA. Role of individual drug in chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Int J Tuber Lung Dis. 2000;4:790–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouillon A. The mutual assistance programme of the IUATLD. Development, contribution and significance. Bull Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 1991;66:159–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espinal MA. Time to abandon the standard retreatment regimen with first-line drugs for failures of standard treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:607–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quy HT, Lan NT, Borgdorff MW, Grosset J, Linh PD, Tung LB, et al. Drug resistance among failure and relapse cases of tuberculosis: Is the standard retreatment regimen adequate? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:631–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mak A, Thomas A, Del Granado M, Zaleskis R, Mouzafarova N, Menzies D, et al. Influence of multidrug resistance on tuberculosis treatment outcomes with standardized regimens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:306–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-240OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revision approved by STAG. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004. WHO/CDS/TB/2003.313 Treatment of tuberculosis: Guidelines for national programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treatment of tuberculosis: Guidelines. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO; 2009. World Health Organization. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, Royce S, Madhukar P, Burman W, et al. Standardized treatment of active tuberculosis in patients with previous treatment and/or with mono-resistance to isoniazid: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh J, Arora A, Garg PK, Thakur VS, Pande JN, Tandon RK. Antituberculosis treatment - induced hepatotoxicity: Role of predictive factors. Post Grad Med J. 1996;71:359–62. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.71.836.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirchandani LV, Joshi JM. Jaundice due to antituberculosis drugs- a dose related phenomenon. J Assoc Phy India. 1995;43:767–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Management of pulmonary tuberculosis, extra-pulmonary tuberculosis and tuberculosis in special situations: API TB consensus guidelines 2006. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:219–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harries AD, Maher D. TB/HIV: A clinical manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. WHO/TB/96.200. [Google Scholar]

- 43.API TB consensus guidelines 2006: Management of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Extra-pulmonary Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis in Special Situations. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:219–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anglaret X, Saba J, Perronne C, Lacassin F, Longuet P, Leport C. Emperic anti-tuberculosis treatment, benefit for early diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Tuber lung Dis. 1994;75:334–40. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crofton J. Persistent fever in pulmonary tuberculosis. BMJ. 1997;314:1347–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7090.1347b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold JA. Fever Curve as an Indicator for Steroid Therapy in Miliary Tuberculosis. Chest. 1961;40:171–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.40.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lenzini L, Rottoli P, Rottoli L. The spectrum of human tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immonol. 1977;27:230–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breen R, Smith C, Bettinson H, Dart S, Bannister B, Johnson M. Paradoxical reactions during tuberculosis treatment in patients with and without HIV co-infection. Thorax. 2004;59:704–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell IA. Treatment of superficial tuberculosis lymphadenitis. Tubercle. 1990;71:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(90)90052-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Humphries M. The management of tuberculosis meningitis. Editorial Thorax. 1992;47:577–80. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.8.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Culuver J. Paradoxical expansion of intracranial tuberculomas during chemotherapy. Lancet. 1984;1:1971. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunath J, Khan FA. Tuberculous and post tuberculous bronchopleural fistula. Chest. 1984;80:697–703. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allen MB, Cooka NJ. Corticosteroids and tuberculosis. Br Med J. 1991;303:871–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6807.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Treasure RL, Seaworth BJ. Current role of surgery in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1405–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00145-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zent C, Smith P. Study of the effect of concomitant food on the bioavailability of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Tub Lung Dis. 1995;76:109–13. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siegler DI, Burley DM, Bryant M, Citron KM, Standen SM. Effect of meals on rifampicin absorption. Lancet. 1971;2:197–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Purohit SD, Sarkar SK, Gupta ML, Jain DK, Gupta PR, Mehta YR. Dietary constituents and rifampicin absorption. Tubercle. 1987;68:151–2. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(87)90034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peloquin CA, Namdar R, Singleton MD, Nix DE. Pharmacokinetics of rifampin under fasting conditions, with food, and with antacids. Chest. 1999;115:12–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rouillon A. “Defaulters” and “Motivation”. Bull Int Union Tuberc. 1972;47:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nahid P, Pai Mand, Hopewell PC. Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Tuberculosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:103–10. doi: 10.1513/pats.200511-119JH. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright J, Walley J, Philip A, Pushpananthan S, Dlamini E, Newell J, et al. Direct observation of treatment for tuberculosis: A randomized controlled trial of community health workers versus family members. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:559–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gasner MR, Maw KL, Feldman GE, Fujiwara PI, Frieden TR. The use of legal action in New York City to ensure treatment of tuberculosis. New Engl J Med. 1999;340:359–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902043400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coker RJ. From Chaos to Coercion: Detention and the Control of Tuberculosis. London: St Martins Press; 2000. p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Developing a system for tuberculosis prevention and care in New York City. New York: United Hospital Fund; 1992. New York City Tuberculosis Working Group. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubos RJ, Dubos J. The White Plague-Tuberculosis, Man and Society. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Preventing Extremely Drug Resistant Tuberculosis: Directly Observed Treatment Is The Only Answer. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2008;50:183–5. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wise J. Fast action urged to halt deadly TB. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:325–420. doi: 10.2471/07.010507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]