Abstract

The objective of the study was to establish the diagnosis of kernicterus as a cause of seizures and abnormal movements in a 1-year-old child. We performed an MRI of the brain of the child on our 1.5 T scanner. The MRI of the patient showed high signals on T2-weighted images in the globus pallidus bilaterally, with no evidence of mass effect. Because of an increased risk of hearing loss, the brain-stem evoked response examination was also performed. The brain-stem evoked response examination showed bilateral severe sensorineural hearing loss. The presence of isolated hyperintense signals in basal ganglia (globus pallidi) was very useful in the evaluation of the structural changes in posticteric bilirubin encephalopathy.

Keywords: Brain, bilirubin, globus pallidus, infants, metabolism

Introduction

Kernicterus is now a rare disorder; however, we came across this case. Kernicterus is a neurological condition in the neonates characterized by cerebral deposition of unconjugated bilirubin.[1] Also known as bilirubin encephalopathy, it is a rare complication of infantile hyperbilirubinemia which results from preferential deposition of bilirubin in the globus pallidus, subthalamic nuclei, hippocampus, putamen, thalamus, and cranial nerve nuclei (especially III, IV, and VI).[2] We report the magnetic resonance (MR) findings in an infant with clinical and laboratory evidence of bilirubin encephalopathy.

Case Report

This term neonate (normal, spontaneous vaginal delivery, Apgar score of 8 at 1 and 5 minutes) was seen at 7 days of age with irritability, opisthotonus, and severe jaundice 1 year back. The initial total bilirubin level was 40 mg/dL. Immediate exchange transfusions reduced the total bilirubin to 24 mg/ dL. By the 15th day, the bilirubin level had dropped to 5.5 mg/dL. The cause of the hyperbilirubinemia was unknown, but was presumed to be of hemolytic in nature. The child was discharged at that time when bilirubin level reduced to normal. No further investigation was done.

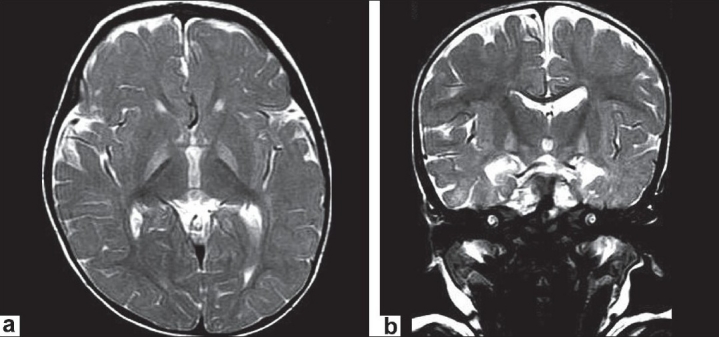

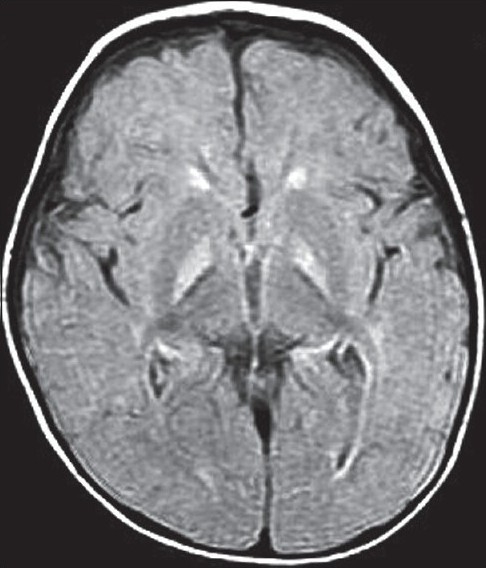

Parents brought the child at the age of 1 year with a complaint of seizures and abnormal movements. The MR examination was performed to detect any neurological abnormality. High signals on T2-weighted images were found in the globus pallidus bilaterally, with no evidence of mass effect [Figures 1a and b]. Similar changes were also noted in FLAIR images in the globus pallidus on both sides [Figure 2].

Figure 1a and b.

Axial T2WIs and coronal T2WIs showing bilateral, symmetrical hyperintense signals in globus pallidi without any mass effect

Figure 2.

Axial FLAIR image showing bilateral, symmetrical hyperintensities in the globus pallidus

The changes in the globus pallidus were consistent with the deposition of unconjugated bilirubin and a complaint of abnormal movements. Because of the increased risk of hearing loss in infants with hyperbilirubinemia, a brain-stem evoked response examination was performed. This examination showed bilateral severe sensorineural hearing loss. The diagnosis of kernicterus was thus made.

Discussion

Kernicterus is a neurological condition resulting from the deposition of unconjugated bilirubin within the brain. The term kernicterus was originally coined by Schmorl in 1903, who reported the postmortem pathologic finding of canary yellow staining of circumscribed areas of the basal ganglia in infants to be associated with neonatal jaundice.[3]

Pathology and pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of kernicterus is not clear; however, factors implicated in concert are hyperbilirubinemia, reduced serum bilirubin binding capacity, opening of the blood brain barrier, and damage to the brain tissue. Hyperbilirubinemia (kernicterus) can be caused by Rh incompatibility, ABO incompatibility, sepsis, or other hemolytic anemias such as glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

There is considerable evidence that hyperbilirubinemia unaccompanied by isomerization cannot cause kernicterus even under extreme conditions. Kernicterus can develop in breast-fed infants in the absence of isoimmune or hemolytic anemias. Kernicterus is rare in adults even with extreme values of bilirubin. The regions most commonly affected are basal ganglia, particularly the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, dentate nucleus, sector H2, H3 of hippocampus, cerebellar vermis, and cranial nerve nuclei, notably the oculomotor, vestibular, and cochlear nuclei. Associated destructive lesions in the white matter, such as periventricular infarcts, have also been reported.[1] The cerebral cortex is spared.[2]

The most accepted theory explaining kernicterus is that kernicterus results from antecedent or concomitant damage to the central nervous system with the breakdown of the blood brain barrier and uptake of albumin-bound bilirubin by the brain.

The microscopic alterations point to the cell membrane as the primary target of injury with secondary involvement of mitochondria. Spongy degeneration and gliosis are most commonly observed anomalies in the bilirubin-stained part of the brain. At autopsy, the most common findings are marked neuronal loss with demyelination and astrocytic replacement.

Plasma albumin normally binds bilirubin rendering it nontoxic; however, free bilirubin is cytotoxic and induces immediate and marked disturbances in brain energy metabolism. Bilirubin can enter the brain, when the serum bilirubin exceeds the normal binding capacity of albumin. In the premature infants, the kernicterus occurs at lower serum bilirubin levels perhaps due to the reduced amount of blood albumin levels.

Disturbed albumin-bilirubin equilibrium results in an increase in the concentration of bilirubin with increased chances of entry of bilirubin in the brain. Greater permeability of the blood brain barrier in patients of asphyxia is another proposed mechanism of entry of bilirubin in the damaged areas of the brain.[1] The role of bilirubin-albumin binding in facilitating the bilirubin entry in the brain is stressed by the fact that kernicterus does not develop in analbuminemic persons.

Clinical features

A neonate with jaundice usually becomes drowsy on the second to fifth day of life. Initial signs may be just fever, monotonus cry and loss of Moro's reflex mimicking sepsis, asphyxia, or hypoglycemia.[1] In approximately 10% of neonates who will develop kernicterus, no signs could be seen. Seizures are uncommon at an early stage. By 2 weeks of age, the infant develops hypertonia with opisthotonus and severe muscle spasm. Later on, hypotonia ensues with the development of syndrome of kernicterus at about 4 years of age.

The posticteric clinical syndrome of kernicterus is related with basal ganglia and consists of an invariable presence of athetosis, often with rigidity and dystonia. Gaze palsy especially involving vertical gaze is another important finding. Auditory problems in the form of hearing loss and receptive aphasia may occur. Vestibular portion of the eighth nerve may also be involved. Severe mental retardation is uncommon; almost 50% of the patients have IQ between 90 and 110 and in approximately 25%, it is between 70 and 90. In about 25% patients, IQ will be less than 70.[4,5]

Brain stem auditory evoked responses are also used for screening in high-risk infants. A correlation can be observed between maximum unbound bilirubin levels and abnormal central conduction times.

The MRI findings in this neonate reflect the typical pathologic findings of kernicterus. In acute hyperbilirubinemia, the findings are hyperintense globus pallidus in T1WIs.[6] Hyperintense signals in T2WIs and FLAIR images in both globus pallidi correspond well with areas of preferential deposition of unconjugated bilirubin in chronic cases of kernicterus. In kernicterus, only subthalamic nuclei are involved with sparing of thalami. This helps to differentiate this condition from ischemic and metabolic disorders.

The important differential diagnoses of acute cases are hypoxia, hypoglycemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, and encephalitis while of chronic cases are dysmyelinating disorders, inborn errors of metabolism, and various degenerative diseases.

Hyperintense signals in the globus pallidus are nonspecific findings; however, along with proper clinical history, examination, and investigation they can establish the diagnosis of kernicterus.

Recently, proton MRS has also been used in the evaluation of kernicterus as a possible metabolic signature.[7] In patients with kernicterus, compared with normal values Tau/Cr, Glx/Cr, and mI/Cr were significantly elevated whereas Cho/Cr was significantly decreased. NAA/Cr was not significantly different from normal values.

Preterm very low weight infants will have low values of blood albumin, and can develop globus pallidal injury which can be confirmed on MRI along with and hearing loss. Serial MRI may be carried out to document a shift from T1W hyperintense signals in acute cases to permanent T2W hyperintense signals in chronic cases.[8]

Two therapeutic modalities, phototherapy and exchange transfusions, have significantly reduced the prevalence of bilirubin encephalopathy.[2]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Friede RL. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. Developmental Neuropathy; pp. 115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turkel SB, Miller CA, Guttenberg ME, Moynes DR, Godgman JE. A clinical pathologic reappraisal of kernicterus. Pediatrics. 1982;69:267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmorl G. Zur Kenntnis des ikterus neonaturum, insbesondere der dabei auftretenden gehirnveranderungen. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1904;6:109–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah Z, Chawla A, Patkar D, Pungaonkar S. MRI in kernicterus. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:55–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2003.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alotaibi SF, Blaser S, MacGregor DL. Neurological complications of kernicterus. Can JNeurol Sci. 2005;32:273–4. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100004182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coskun A, Yikilmaz A, Kumandas S, Karahan OI, Akcakus M, Manav A. Hyperintense globus pallidus on T1-weighted MR imaging in acute kernicterus: Is it common or rare? Eur Radiol. 2005;15:1263–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oakden WK, Moore AM, Blaser S, Noseworthy MD. 1H MR Spectroscopic Characteristics of Kernicterus: A Possible Metabolic Signature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1571–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Govaert P, Lequin M, Swarte R, Robben S, De Coo R, Weisglas-Kuperus N, et al. Changes in Globus Pallidus With (Pre)Term Kernicterus. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6):1256–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]