Sir,

A 7 year old male child presented with a progressive illness characterized by fever (4 months), headache (2 months), vomiting (1 month), altered sensorium (7 days) and generalized tonic clonic seizures for a day. There was a family history of tuberculosis. He had neck rigidity with brisk deep tendon reflexes. CT scan revealed hydrocephalus due to an obstruction between the third and the fourth ventricle with basal exudates. Lumbar CSF showed 120 cells with 90% lymphocytes, proteins of 208 mg% and CSF sugar of 31 mg% against blood sugar of 61 mg%. CSF smears and cultures were negative. On the basis of prolonged history, positive family history and lymphocytic predominance in CSF, a diagnosis of tubercular meningitis was made. The child was started on four-drug anti-tubercular therapy (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) and compliance to drug therapy was ensured. A ventriculo-peritoneal shunt was inserted and it resulted in a significant neurological improvement. He remained well for about 6 months after which he presented with headache for 10 days, difficulty in walking for 7 days and fever for 4 days. The sensorium was normal. There were no signs of meningeal irritation or raised intracranial pressure. There was right-sided ptosis, marked truncal ataxia with some signs of limb ataxia, more so on the right side. The representative sections of MRI of the head are illustrated in the [Figures 1–3].

Figure 1.

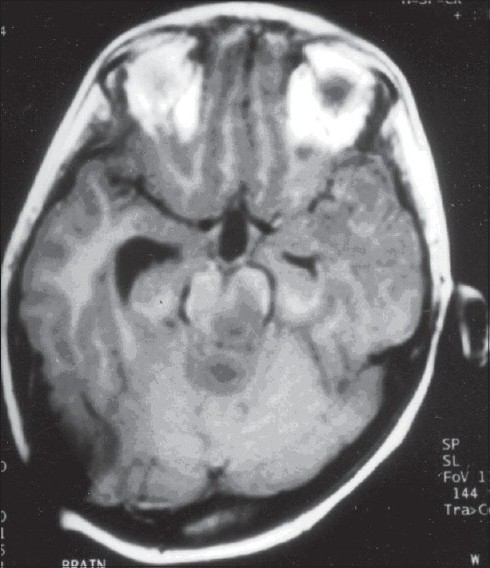

MRI head, T1 weighted axial image

Figure 3.

MRI Head, T2 weighted axial image

The possible reasons for the secondary deterioration were:

Ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunction: Headache and cerebellar signs could be explained due to shunt malfunction but right eye ptosis couldn’t be explained.

Development of stroke in posterior circulation on the top of the basilar artery territory. There was no history of acute onset to suggest stroke. Moreover, the stroke in tuberculous meningitis tends to manifest during the early part of the disease process, whereas the secondary deterioration in the index case occurred after an asymptomatic period of 6 months.

Similarly, secondary resistance of mycobacterium tuberculosis to antitubercular drugs is unlikely as there was an excellent response. There were no signs of meningeal irritation. The child enjoyed an asymptomatic period of 6 months before secondary deterioration. Moreover, the compliance to anti-tubercular therapy was ensured.

The paradoxical appearance of tuberculomas, whilst on antitubercular therapy seems most likely. A greater severity of truncal vis-à-vis limb ataxia denotes vermian or paravermian cerebellar involvement or its connecting pathway.[1] Right eye ptosis without extraoccular muscle paresis or pupillary abnormalities indicates partial third nerve palsy or levator palpebral superioris subnucleus involvement in the high midbrain (intra-axial). Lesion in the supranuclear pathway on the opposite site can also explain predominantly unilateral ptosis.[2]

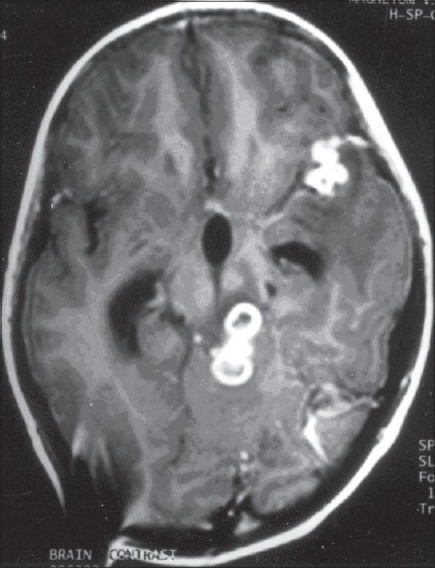

T1 weighted axial section [Figure 1] shows hypo intense lesions in left side of midbrain, cerebellar vermian region and in the anterior part of the left temporal lobe. The right temporal horn of the lateral ventricle is dilated. On gladolinium enhancement [Figure 2], there are conglomerate ring enhancing lesions in the above-mentioned areas. In T2 weighted axial section [Figure 3], there is hyper intensity in the above-mentioned areas and most of the left temporal lobe. In addition, there are a few lesions with a central hyperintensity and a peripheral hypointense ring; these findings are consistent with a radiological diagnosis of multiple tuberculomas.[3]

Figure 2.

MRI Head, T1 weighted postcontrast axial image

The development of tuberculomas in cases of tuberculous meningitis whilst on anti-tubercular therapy, and in spite of satisfactory compliance is designated as paradoxical response or therapeutic paradox. This therapeutic aberration usually occurs in the initial 2-3 months of therapy and generally coincides with the tapering of steroids.[4] However, cases have been reported up to 18 months after starting anti-tubercular therapy.[5] The probable explanation for development of fresh tuberculomas or an increase in size of pre-existing lesions, in spite of effective chemotherapy, is a consequence of interplay between the hosts‘immune responses and the effects of mycobacterial products. Active tuberculosis can result in suppression of delayed type hypersensitivity responses (anergy). Once active TB is under control and immunosuppression is resolved, enhanced delayed type of hypersensitivity can lead to activation and accumulation of lymphocytes and macrophages at the site of bacillary deposition or toxin production when the bacilli die. If the activation occurs at the site of microscopic foci in CNS, tuberculomas appear. If it occurs at the site of macroscopic tuberculomas, they enlarge.[6]

The introduction of oral steroids leads to a very good response. In the index case, the headache became passive within 2 days and the gait abnormalities started improving to become passive over a few days after the addition of steroids to same anti tubercular drug regimen. Right eye ptosis disappeared and truncal and limb ataxia also became passive. There is no evidence that a change in anti-tubercular drug regimen therapy is warranted as exemplified in our case. The anti-inflammatory effects of steroids diminish the neurological symptoms over a short period.[6]

Final Diagnosis

Paradoxical appearance of tuberculomas whilst on antitubercular therapy.

Learning points

Appearance or increase in the size of tuberculomas may occur during therapy.

The phenomenon usually manifests within initial few months, but is known to occur till as late as 18 months after start of anti-tubercular therapy.

The phenomenon has an immunological basis and responds to a short course of steroids.

A change in therapy or a prolonged duration of therapy is not warranted

References

- 1.Patten J, editor. Neurological differential diagnosis. 2nd edn. London: Springer; 2000. The extrapyramidal system and the cerebellum; pp. 178–212. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh FB, editor. Clinical Neuro-Opthalmology. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins company; 1957. The Eyelids and the Extraoccular Muscles; pp. 185–275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katariya S. CNS Infections. In: Berry M, Suri S, Chowdhury V, et al., editors. Diagnostic Radiology, Neuroradiology Including Head and Neck Imaging. 1st edn. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2001. pp. 44–65. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abduljabbar M. Paradoxical response to chemotherapy for intracranial tuberculoma: two case reports from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1991;94:374–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash Rao G, Rajendra Nadh B, Hemaratnam A, et al. Paradoxical progression of tuberculous lesions during chemotherapy of central nervous system tuberculosis. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1995;83:359–362. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afghani B, Lieberman JM. Paradoxical enlargement or development of intracranial tuberculomas during therapy: Case report and review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994;19:1092–1099. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]