Abstract

Background:

Intracranial meningiomas are rare tumors in children accounting for 0.4-4.6% of all primary brain tumors in the age group of 0-18 years.

Objective:

To retrospectively analyze the epidemiological profile, clinical features, radiological findings, type of excision, histopathological findings, and overall management profile of these patients.

Materials and Methods:

Eighteen consecutive cases of meningioma in patients under 18 years of age admitted and operated at our institute between the years 1974-2005 were included in this study.

Results:

The mean age of patient at presentation to our hospital was 12.81 years. The male to female ratio was 1.57:1. The median preoperative duration of symptoms was 1.2 years. An increased incidence was seen in patients with neurofibromatosis. Intraventricular and skull base locations were common. Total tumor excision was achieved in all cases.

Conclusion:

A higher incidence of atypical and aggressive meningiomas is seen in children. Children with complete resection and a typical benign histology have a good prognosis.

Keywords: Meningioma, childhood meningioma, pediatric neoplasms, neurofibromatosis

Introduction

Meningiomas occur most commonly in the fifth decade of life, accounting for approximately 15-20% of primary intracranial tumors.[1] Intracranial meningiomas in children and adolescents are rare tumors. In most large series, the incidence of meningiomas before the age of 16 years ranges from 0.4 to 4.6% of all primary brain tumors in this age group.[2–7] They account for 0.9-3.1% of all intracranial meningiomas.[8–10] The female preponderance found in adult patients is not seen in children, the reported male- to-female ratio in children being 1.2:1.[1,11] Risk factors for the development of meningiomas include the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type two (NF-2) and a history of radiation therapy, the so-called radiation- induced meningiomas.[12] Meningiomas in children have been considered by some to be more aggressive than their adult counterparts.[13–16]

Materials and Methods

Eighteen consecutive cases of meningioma in patients under 18 years of age admitted and operated at Bombay hospital institute of medical sciences, Mumbai, India, by senior author (Dr. SNB) between the years 1974-2005 were included in this study. All cases were confirmed by radiological, operative, and histopathological findings. We have tried to retrospectively analyze the epidemiological profile, clinical features, radiological findings, type of excision, histopathological findings, and overall management profile of these patients. All patients/relatives were called for the follow- up or an attempt was made to at least get an interview on telephone. As and where possible, we have made an attempt to determine the differentiating features between adult and pediatric meningiomas.

Results

Incidence

We operated a total of 934 meningioma cases between the years 1974-2005, of which 18 cases were in the age group of 0-18 years. Thus, childhood meningiomas accounted for 1.92% of total meningiomas in our study.

Sex and Age

Age at diagnosis varied from 9 months to 18 years. We had only one child with presentation under 1 year of age. The maximum incidence of meningiomas was seen in the second decade of life. Thirteen out of 18 cases presented in the second decade. The mean age at presentation was 12.81 years. There were 11 males and 7 females in our series. The male-to-female ratio was 1.57:1.

Presenting symptoms and signs

The most common presenting signs and symptoms were due to raised intracranial pressure or seizure. The main presenting symptoms were seizure (8 patients), headache (6 patients), impairment of vision (2 patients), vomiting (3 patients), proptosis (2 patients), increased head size (1 patient), and occipital swelling (1 patient). The median pre-operative duration of symptoms was 1.2 years.

The most common clinical sign seen was papilledema (7 patients) followed by monoparesis (4 patients), marked impairment of vision (2 patients), proptosis (2 patients), tense anterior fontanelle (1 patient), occipital swelling (1 patient), and neurofibromatosis (2 patients).

Neuro-radiology

Our series includes patients operated between the years 1974 and 2005. Hence, patients were investigated with varied available neuroradiological modalities such as plain X-ray of skull (1 patient with calcified tumor), cerebral angiography (2 patients), CT scan (11 patients), MRI (2 patients), and CT scan + MRI (2 patients).

Location

Seventeen cases were supratentorial and 1 case was infratentorial in location. The tumors were located in the cerebral convexity in six patients, intraventricular in four patients, skull base in three patients, Falcine in two cases, parasellar in one patient, tentorial in one case and in posterior fossa in one patient.

Lesion characteristics

Tumor was homogenous in appearance in most of the cases visualized with CT/MRI. Intra-tumoral calcification was seen in two cases. Intra-tumoral cystic changes were seen in two cases. Hyperostosis was seen in three cases.

Tumor excision

Total excision of tumor was achieved in all cases. In 14 patients, total excision was achieved in one stage. Three patients required two-stage surgeries for total excision and one patient required three-stage surgeries to achieve complete excision.

Peri-operative mortality

One patient expired postoperatively due to brainstem disturbances. He turned out to have malignant meningioma on histopathology. The mean peri-operative mortality was 5.5%.

Histopathology

Histopathology showed fibroblastic meningioma in three patients, meningothelial in one patient, transitional in eight patients, angioblastic in three patients, sarcomatous in one patient, aggressive syncitial in one patient, and malignant meningioma in one patient.

Adjuvant therapy

Postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy was given to four patients; three patients with histopathology suggestive of angioblastic meningioma and one patient with aggressive syncitial meningioma. One patient with sarcomatous meningioma could not be given radiation, as the age at diagnosis was only 9 months. However, patient had no recurrence even at 14 years of follow-up.

Follow up and recurrence

An attempt was made to get follow-up of all patients. The period of follow-up ranged from 1 to 26 years with a mean follow-up of 6.1 years. We documented two recurrences in our series on follow-up. The histopathology in patients with recurrence was aggressive syncytial in one patient and transitional in the other patient. Both the patients had a total excision during their first surgery. The patient with transitional meningioma had a falcine meningioma and may be some microscopic remnant must have been left behind, as falx was not excised. During his redo surgery, we achieved a total excision of falx. In a patient with aggressive syncytial meningioma, recurrence was seen after 2 years and in a patient with transitional meningioma, recurrence was seen after 5 years.[Figure 1,2]

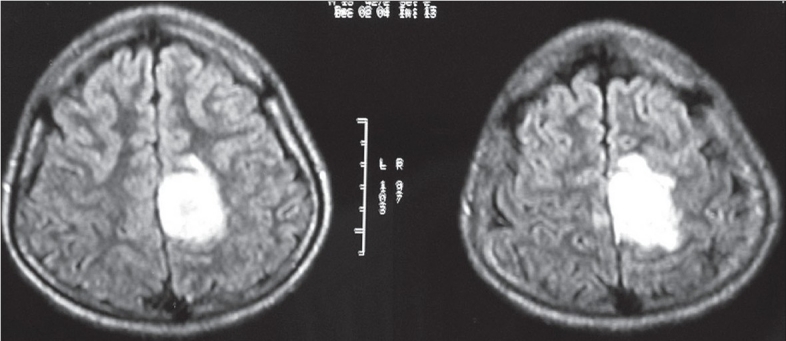

Figure 1.

MRI Brain with Gadolinium: Axial view showing intensely enhancing falcine meningioma

Figure 2.

MRI brain with gadolinium: Coronal view showing the same falcine meningioma

Discussion

Meningiomas are uncommon neoplasms in the pediatric age group and differ in various clinical and biological aspects from meningiomas in the adult population.[17] It was reported that the frequency was less than 5% of all pediatric brain tumors.[12] Its incidence as reported by Mendiratta et al.[7] is 1.5% of total meningiomas seen in the population. In our series of childhood meningiomas, i.e. meningiomas in children under 18 years of age, the incidence was 1.92%.

Children with meningiomas present late in the first decade or early in the second decade of life.[10,11,18,19] In our series, the mean age at presentation was 12.81 years. Infantile meningioma is extremely rare. Less than 30 cases of meningiomas in infants less than 12 months of age have been reported.[10,19,20] The incidence of infantile meningiomas in different series of childhood meningiomas varies from 2.4%[10] to 6.9%[8–10] In our series, only one case (5.5%) of infantile meningioma was seen.

In contrast to adult meningiomas where a female preponderance is seen,[21] childhood meningiomas showed a distinct male predominance.[8,9,10,12,17,22] In our series, there were 11 males and 7 females. The male-to-female ratio was 1.57:1. The greater occurrence of meningiomas in males could be related to an absence of the effect of sex hormones on corticosteroid receptors in meningioma cells for low blood concentrations.[23–25] This suggests that different pathogenic factors might account for the occurrence of meningiomas in children and adults. Some studies on genetic aberrations in meningiomas in children show no differences from meningiomas in adults.[22]

Signs and symptoms related to raised intracranial pressure are most common in childhood meningiomas. Meningiomas in children grow faster and occur more frequently in the ventricles than those in adults; therefore, cerebrospinal fluid circulation can be easily obstructed in the early stage, which results in increased intracranial pressure.[19] The incidence of seizure in childhood meningiomas(25%)[8–10] is lower than that in adult meningiomas (29-40%).[1] In our series, seizure was seen in 44.4% of cases (eight cases), i.e., an incidence similar to adult patients.[21] Focal seizure occurs more commonly in adults, whereas generalized seizure occurs more in children.[26] In our series, six patients presented with generalized seizures and only two patients presented with focal seizure.

In different series in the literature, 0-41% of childhood meningiomas are associated with neurofibromatosis,[8–10] while the Figure is only 0.35% for adult meningiomas.[21] In Erdincler et al. series, 41% of childhood meningiomas were associated with multiple neurofibromatosis, of which 58% were NF-1 and 42% NF-2. In our series, we had one case each with NF-1 and NF-2, i.e. an incidence of 11.11%.

The frequency of intraventricular meningiomas is very high (12%)[22] as compared to 0.5-4.5% in adults.[27,28] The propensity for growth into the ventricular system is explained by the inclusion of arachnoid cells in the choroid plexus and velum interpositum.[29,30]

In our series, 22.22% of cases had an intraventricular meningioma. The lack of dural attachment is another frequent occurrence in pediatric meningiomas (28.5%), whereas it is extremely rare in adult patients.[13,15] This lack of dural attachment is probably due to derivation of the tumor from leptomeningeal elements lodging within the parenchyma or in or near the ventricles rather than from the dura mater.[31]

An important feature distinguishing childhood meningiomas from adult meningiomas is their peculiar location. Convexity meningiomas are most common in adult meningiomas, while childhood meningiomas have other peculiar location that increases complexity in their management.[11,32] In our series of 18 cases, only 6 cases were having convexity meningiomas, 4 skull base, 4 intraventricular, 1 tentorial, 1 posterior fossa, 2 falcine and one case was parasellar in location. In children, meningiomas have also been rarely reported to occur in the third ventricle[33] intraparenchymally[34] and in sylvian fissure.[35]

Various series in the literature have also documented a high incidence of cystic changes in meningiomas in children.[11,36] In our series, we had two patients with cystic changes in meningiomas. In series of Tufan et al., 4 out of 11 meningiomas showed cystic changes.[36]

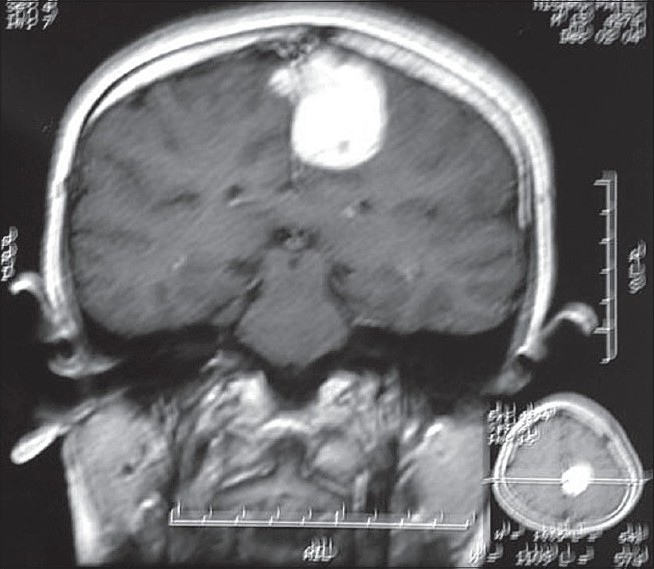

Surgical excision has been the treatment of choice for these tumors. Surgical management poses a formidable challenge considering their peculiar location, larger size at presentation, relatively less blood volume in children, and the risks of prolonged surgery like hypothermia, massive blood transfusion, etc. Nevertheless, with progress in microneurosurgical and anesthesiological techniques and considering the benign nature of disease, surgical excision remains the modality of choice. Also in children with residual tumor or regrowth, the risk of radiation to the developing brain favors redo surgery over radiation therapy. Pre-operative embolization is not routinely practised in children and there are no conclusive data on its benefits in children.[37,38] However, the morbidity of the procedure due to small caliber of vessels in children should be kept in mind. In our series, pre-operative Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) with tumor embolization was done only in one case with skull base meningioma.[Figure 3]

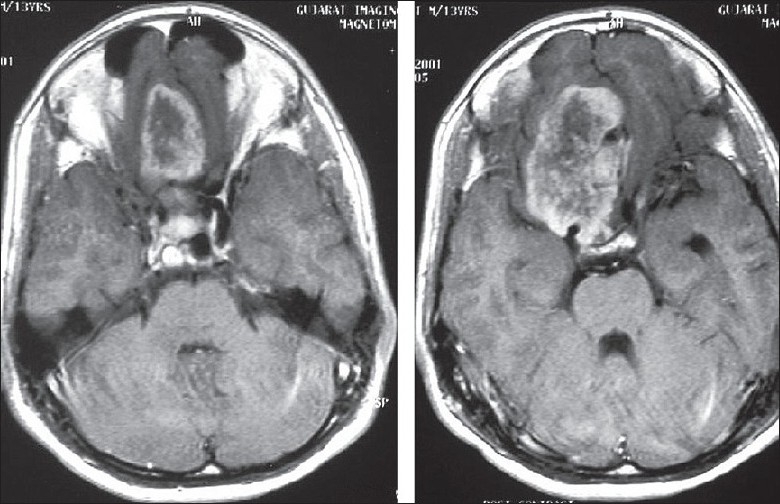

Figure 3.

MRI brain: Axial view showing skull base meningioma

In our series, surgical excision was done in all cases. Gross total excision was achieved in 14 cases (77.78%) in the first attempt. In three patients, the biopsy was done first followed by a second stage complete excision. In one patient, complete excision was done in three stages, i.e. biopsy followed by partial excision followed by complete excision in third stage. We had only one patient with 5.5% peri-operative mortality rate. Various studies in the literature between the years 1970 and 2006 have shown a peri-operative mortality rate of 0.3-10%.[22] Various interventions have been advised in the literature to reduce the peri-operative mortality like pre- operative CSF diversion, anti-edema measures, anti- epileptic prophylaxis, use of postoperative ventilation, etc.[22]

Histopathological examination revealed fibroblastic meningioma in three cases, meningothelial meningioma in one, eight were transitional, three were angioblastic, one was sarcomatous, one was aggressive syncytial meningioma, and one case was malignant type. Histopathology of these tumors in the pediatric population varied from those in the adult population. Overall, most series have shown a high incidence of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas in children as compared to the adult population.[17] In our series, six patients (33.33%) had an atypical or anaplastic histopathology. In the literature, adjuvant therapy has been advised in these patients in the form of radiation therapy.[17] In series of Perry et al., they noted a high frequency of brain invasion in pediatric meningiomas and reported them to be phenotypically and genotypically aggressive as compared to the tumors in adults.[39] Immunohistochemical proliferative markers have been studied by Sandberg et al.[40] They documented higher MIB-1 LI in atypical or malignant tumors as compared to tumors without atypia. On the other hand, median MIB-1 for pediatric meningiomas without histopathological atypia did not differ significantly from that for adult meningiomas without atypia.

In our cases with atypical and aggressive histopathologies, four were given adjuvant radiotherapy. One patient with malignant meningioma expired postoperatively and one patient with sarcomatous meningioma could not be given radiation, as age at the time of surgery was only 9 months. This patient was followed up closely and has not shown any recurrence even after 14 years.

We documented two recurrences in our series during the follow-up. The period of follow-up ranged from 1 to 26 years with a mean follow-up of 6.1 years. Histopathology in patients with recurrence showed aggressive syncytial in one case and transitional in the other case.

Different series in the literature have shown a recurrence rate of approximately 13%.[22] Recurrence seems to be strictly related to incomplete resection and/or histologic subtype of the meningioma. Atypical, aggressive, and meningiomas with cortical invasion show a higher rate of recurrence.

Overall, 16 patients improved neurologically postoperatively, one remained static, and one patient died postoperatively.

Conclusion

Meningiomas in children are rare tumors and account for 1.92% of total meningiomas. Meningiomas in children show some characteristic differences when compared with their adult counterparts. These include slight preponderance in male subjects, higher incidence of intraventricular and skull base location, and frequent cystic changes. Pediatric meningiomas tend to present with features of raised intracranial pressure and seizure. An increased incidence of meningiomas is seen in patients with neurofibromatosis.

Total surgical excision should be performed wherever feasible, even if it requires staged resection. Advances in microneurosurgical and anesthesiological management have considerably reduced the operative morbidity and mortality. There is a higher incidence of atypical and aggressive histological subtypes in the pediatric population. Children with complete resection of meningioma and a typical benign histology have a good prognosis like their adult counterparts.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Germano IM, Edwards MS, Davis RL, Schiffer D. Intracranial meningiomas of the first two decades of life. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:447–53. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.3.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodian M, Lawson D. Intracranial neoplastic diseases of childhood: A description of their natural history based on a clinico-pathological study of 129 cases. Br J Surg. 1953;40:368–92. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004016213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuneo HM, Rand CW. Vol. 15. Springfield IL, Charles C, Thomas: 1952. Brain tumors of childhood. [Google Scholar]

- 4.French L. Intracranial and cranial tumor. In: Jackson P, Thompson F, editors. Pediatric Neurosurgery. Oxford UK: Blackwell; 1959. pp. 226–94. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keith HM, Craig WK, Kernohan JW. Brain tumors in children. Pediatrics. 1949;3:838–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibel SA, Wara WM, Sheline GE, Townsend JJ, Boldrey EB. The treatment of meningiomas in childhood. Cancer. 1976;37:2709–12. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197606)37:6<2709::aid-cncr2820370621>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendiratta SS, Rosenblum JA, Strobos RJ. Congenital meningioma. Neurology. 1967;17:914–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.9.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang K, Chen J, Jiang X. Intracranial meningiomas in children. Chin J Clin Neurosurg. 2000;5:21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang J, Yang H, Huang Q. Diagnosis and treatment of pediatric meningiomas. Chin J Neurosurg. 2002;18:408. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erdinçler P, Lena G, Sarioğlu AC, Kuday C, Choux M. Intracranial meningiomas in children: Review of 29 cases. Surg Neurology. 1998;49:136–41. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrante L, Acqui M, Artico M, Mastronardi L, Rocchi G, Fortuna A. Cerebral meningiomas in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 1989;5:83–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00571115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene S, Nair N, Ojemann JG, Ellenbogen RG, Avellino AM. Meningiomas in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008;44:9–13. doi: 10.1159/000110656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake JM, Hendrick EB, Becker LE, Chuang SH, Hoffman HJ, Humphreys RP. Intracranial meningiomas in children. Pediatr Neurosci. 1985-1986;12:134–9. doi: 10.1159/000120235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odom GL, Davis CH, Wodhall B. Brain tumors in children-Clinical analysis of 164 cases. Pediatrics. 1956;18:856–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crouse SK, Berg BO. Intracranial meningioma in childhood and adolescence. Neurology. 1972;22:135–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.22.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell EJ, George AE, Kricheff II, Budzilovich G. Atypical Computed Tomographic features of intracranial meningioma. Radiology. 1980;135:673–82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.135.3.7384454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arivazhagan A, India Devi B, Kolluri SV, Abraham RG, Sampath S, Chandramouli BA. Pediatric intracranial meningiomas: Do they differ from their counterparts in adults? Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008;44:43–8. doi: 10.1159/000110661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry A, Dehner LP. Meningeal tumors of childhood and infancy: An update and literature review. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:386–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Li F, Zhu S, Liu M, Wu C. Clinical features and treatment of meningiomas in children: Report of 12 cases and Literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008;44:112–7. doi: 10.1159/000113112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molleston MC, Moran CJ, Roth KA. Infantile meningiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21:195. doi: 10.1159/000120835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z. 1st ed. Hubei: Hubei Technology Publishing House; 2005. Zhongcheng's Neurosurgery; pp. 587–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caroli E, Russillo M, Ferrante L. Intracranial meningiomas in children: Report of 27 new cases and critical analysis of 440 cases reported in the literature. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:31–6. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210010801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deen HG, Scheithauer BW, Ebersold MJ. Clinical and pathological study of meningiomas of the first two decades of life. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:317–22. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.3.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markwalder TM, Seiler R, Zava DT. Antiestrogenic therapy of meningiomas: A pilot study. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:245–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(85)90030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donnell MS, Meyer GA, Donegan Wl. Estrogen receptor protein in intracranial meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:499–502. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.4.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Im SH, Wang KC, Kim SK, Oh CW, Kim DG, Hong SK, et al. Children meningioma: Unusual location, atypical radiological findings and favourable treatment outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17:656–62. doi: 10.1007/s003810100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen HJ, Lui CG, Chen L. Meningioma in anterior third ventricle in child. Childs Nerv Syst. 1986;2:160–1. doi: 10.1007/BF00270848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merten DF, Gooding CA, Newton TH, Malamud N. Meningioma of childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr. 1974;84:696–700. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(74)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumgartner JE, Soreson JM. Meningioma in the pediatric population. J Neurooncol. 1996;29:223–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00165652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobata H, Kondo A, Iwasaki K, Kusaka H, Ito H, Sawada S. Chordoid meningioma in a child. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:319–23. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.2.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artico M, Ferrante L, Cervoni L, Colonnese C, Fortuna A. Pediatric cystic meningioma: Report of three cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:137–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00570253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Rocco, Di Renzo A. Meningiomas in childhood. Crit Rev Neurosurg. 1999;9:180–8. doi: 10.1007/s003290050129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang PP, Doyle WK, Abbott IR. Atypical meningioma of the third ventricle in a 6 year old boy. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:312–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199308000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohama I, Sohma T, Nunomura K, Igarashi K, Ishikawa A. Intraparenchymal meningioma in an infant: A case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1996;36:598–601. doi: 10.2176/nmc.36.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan SS, Ojemann JG, Park TS. Pediatric sylvian fissure meningioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;36:275–6. doi: 10.1159/000058433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tufan K, Dogulu F, Kurt G, Emmez H, Ceviker N, Baykaner MK. Intracranial meningiomas of childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000084858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oka H, Kurata A, Kawano N, Saegusa H, Kobayashi I, Ohmomo T, et al. Pre-operative superselective embolisation of meningiomas: Indications and limitations. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:67–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1006196420398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Probst EN, Grzyska U, Westphal M, Zeumer H. Pre operative embolisation of meningiomas with a fibrin glue preparation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1695–702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry A, Giannini C, Raghavan R, Scheithauer BW, Banerjee R, Margraf L, et al. Aggressive phenotypic and genotypic features pediatric and NF-2 associated meningiomas: A clinicopathologic study of 53 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:994–1003. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.10.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandberg DI, Edgar MA, Resch L, Rutka JT, Becker LE, Souweidane MM. MIB-1 staining index of pediatric meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:590–7. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200103000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]