Abstract

Objectives:

This designed was designed to estimate the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in infants of up to 6 months of age and to assess clinical and laboratory indicators as predictors of Chlamydia etiology.

Materials and Methods:

A hospital-based study was conducted in Department of Pediatrics, Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, India, where infants up to 6 months of age (n=50) with features of lower respiratory tract infection of at least 1 week duration and fulfilling the inclusion criteria were assessed clinically and underwent laboratory investigations using hemogram, Chest X-ray, and IgM ELISA.

Results:

Out of 50 infants, 12 (24%) were tested positive by IgM ELISA test for C. trachomatis infection. In age group of up to 2 months 25% positivity was seen whereas it was found to be 31.81% in age group of 2–4 months and 15% in age group 4–6 months. With the ‘P’ value less than 0.05, it was found that there may be an association of seropositivity of C. trachomatis with duration of cough and absolute eosinophil count.

Conclusion:

Chlamydia trachomatis is an important cause of lower respiratory tract infection in infants below six months of age. The prolonged duration of cough and increased absolute eosinophil count may be good indicator of its etiology.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Infants, Seroprevalence

INTRODUCTION

Acute lower respiratory tract infection (ALRI) is the leading cause of death in children.[1,2] In developing countries, it causes 19% of all deaths among children younger than 5 years and 8.2% of all disability. In these countries, it is estimated that ALRI kills 4 million children every year: 3 million of these die from pneumonia.[3]

There is a current widely held belief that the causative organisms vary according to the age of the child, viruses being most common in children under 5 years old. Respiratory syncitial virus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, influenza virus, and more recently metapneumovirus virus[4] have all been identified in this age group. Pneumocystis carinii had been implicated as a causative agent of pneumonia in malnourished and immunodeficient children.

Etiology of pneumonia in younger infants less than 6 months of age is not very well documented. Nearly half of all pneumonia occurring in children less than 5 years age group of children occurs in those less than 6 months of age. Pneumonia in this age group is the leading cause of death, accounting for about 16% of all deaths in the neonatal period. Moreover, pneumonia in this age group may lead to septicemia and meningitis due to physiological and immunological immaturity in these infants. Documentation of the causative agents of the lower respiratory tract infection in this age group is therefore important for therapy of pneumonia. Chlamydia trachomatis has been documented to be pathogen causing lower respiratory tract infection in this age group. Different studies showed that Chlamydia pneumonae is a common respiratory pathogen, responsible for about 10% of community acquired pneumonia (CAP).[5]

In C. trachomatis pneumonia, the illness tends to be of subacute onset. The organism may be causally associated with wheezing, asthmatic bronchitis, and adult onset asthma.[6] Fever is usually absent.

The infant usually acquires the organism during passage through the birth canal from chronically infected mothers. Usual age of presentation is at 3 weeks to 3 months of life, but sometimes patient presents at even younger age. The prevalence of C. trachomatis was reported as 15.8% in infants younger than 3 months of age, who had pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis.[7] Similarly, a different study showed that C. trachomatis is not an infrequent cause of respiratory distress even in early childhood, where 8/103 (7.8%) preterm neonates were positive for C. trachomatis as early as within 24 h of life.[8] Most cases of LRTI respond to conventional antibiotics such as amoxicillin, co-trimaoxazole, or oral cephalosporin within 1 week, but in C. pneumoniae the course of illness is protracted and a specific diagnosis is important because β-lactam antibiotic treatment is ineffective in infections due to Chlamydia.[9] Macrolides are treatment of choice for this type of pneumonia.

Culture of the organism from nasopharyngeal secretions remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of C. trachomatis infection. Ligase chain reaction, direct immunofluorescence test, microimmunofluorescence test, and ELISA are the other tests used for diagnosis of C. trachomatis.[10,11] ELISA test is relatively easier to carry out, less costly, have good sensitivity (75%) and specificity (88%). Other above investigations were not available in our hospital. In developing country like India, cost factor is very important, so we used ELISA method in our study.

This study was conducted to find out the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis infection in young infants up to 6 months of age with lower respiratory tract infection of more than 1 week in Bundelkhand region. These patients were also assessed for clinical indicators (association with conjunctivitis, fever, and cough) and laboratory indicators (absolute eosinophil count and chest X-ray) as predictors of Chlamydial etiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion criteria

Infants up to 6 months of age, attending Pediatric OPD or admitted in Pediatrics ward of Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College, Jhansi.

Cough and tachypnea with or without chest wall retraction for more than 1 week duration despite conventional treatment for pneumonia. Tachypnea was defined as respiratory rate more than 60 per minute in a child less than 2 months or more than 50 per minute in an infant two or more than two months.

Exclusion criteria

Infants with defects known to be associated with prolonged lower respiratory tract infection such as congenital heart disease, congestive heart failure, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, or a history consistent with tracheooesophageal fistula were excluded from study.

Design and sample size

This was a cross-sectional study, where 50 cases were taken to find out the prevalence of C. trachomatis associated pneumonitis in patients with lower respiratory tract infection in the first 6 months of life.

Methodology

This study was conducted in the Department of Pediatrics, Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College, Jhansi. Data were collected over a period of 1 year in active collaboration with Department of Microbiology after taking due clearance from the ethical committee. Infants up to 6 months of age, attending Pediatric OPD or admitted in Pediatrics ward of Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College, Jhansi, who presented with features of lower respiratory tract infection of at least 1 week duration and fulfilling the inclusion criteria were taken as subjects. The subjects were divided into three groups on the basis of age, into less than 2 months, 2–4 months, and 4–6 months. A complete clinical examination was done. In the investigations hemoglobin percent, total leukocyte count, absolute eosinophil count, and chest X-ray were done. Blood samples were withdrawn from a peripheral vein with all precautions and asepsis. Serum was separated by centrifugation and stored in deep freezer at -20°C. Repeated freeze-thawing was avoided. Grossly hemolysed, icteric, or grossly lipemic samples were discarded. Measurement of serum IgM antibody against C. trachomatis was detected using ELISA method, following all the steps given by the manufacturer of ELISA kit (CHLM0070, Novatec, Immundiagnostica, Germany). The gold standard for diagnosis of C. trachomatis pneumonia is isolation by culture of a specimen from the nasopharynx. However, this facility was not available in our hospital and ELISA test is a simple and reliable test which gives rapid results, so we used ELISA method in our study. The association among C. trachomatis and fever, duration of cough, mode of delivery, conjunctivitis, total leukocyte count, and absolute eosinophil count was measured using χ2 test and Fisher's exact test.

Undertaking of consent

During the conduct of study, detailed information about the study was given to the parents to obtain their willingness to participate in the study and for providing sera samples of the infants with informed and written consent of the parents.

RESULTS

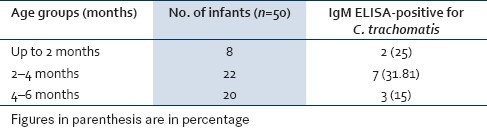

Fifty cases were recruited into the study. There were 8 (16%) infants below 2 months, 22 (44%) between 2 and 4 months, and 20 (40%) between 4 and 6 months of age group [Table 1]. In 50 infants of up to 6 months of age with atypical features of lower respiratory tract infection, the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis was found to be 12 (24%) by ELISA method. Test positivity in three defined age group of less than 2 months, 2–4 months and 4–6 months was 2 (25%), 7 (31.81%), and 3 (15%), respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age wise distribution of cases with positivity for IgM antibodies to C. trachomatis

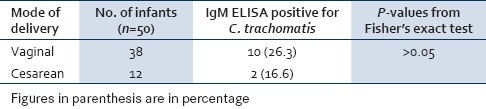

There were 40 (80%) males and 10 (20%) females. Around 38 (76%) infants were born by vaginal delivery and 12 (24%) by cesarean section. Positivity for C. trachomatis was not significantly associated with mode of delivery [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association of C. trachomatis positivity with mode of delivery

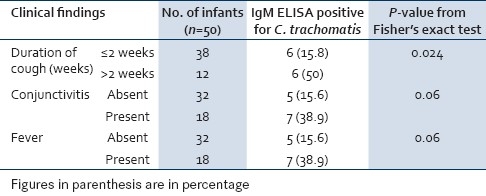

Among 50 infants, duration of cough was prolonged in 38 (76%) infants. Out of these 38 infants, 6 (15.8%) infants were found to be positive for C. trachomatis. In remaining 12/50 (24%) infants where duration of cough was less than 2 weeks, 6/12 (50%) infants were found to be positive for C. trachomatis. Duration of cough and seropositivity of C. trachomatis was found to be statistically significant [Table 3]. Seven (58.3%) patients with C. trachomatis etiology had some elements of conjunctivitis. Thus, while the presence of conjunctivitis was quite reliable as a marker of Chlamydia infection, but the absence of conjunctivitis did not rule out infection with C. trachomatis. Seven (58.3%) infants positive for C. trachomatis were afebrile.

Table 3.

Association of C. trachomatis positivity with clinical features

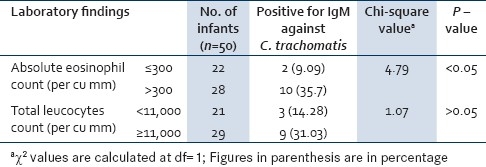

Association of eosinophilia (i.e., absolute eosinophil count more than 300 per cu mm) with positivity of C. trachomatis was found to be statistically significant. A total of 83.3% of infants positive for C. trachomatis had eosinophilia [Table 4].

Table 4.

Association of C. trachomatis positivity with laboratory findings

Among 12 infants, who were positive for C. trachomatis, 75% did not have leucocytosis (i.e., leucocytes count more than 11,000 per cu mm). These results may be due to low antigenicity of C. trachomatis. X-rays of the infants positive for C. trachomatis had variable findings. Most common finding in these X-rays was the patchy infiltrates. Besides that minimal infiltrates and hyperinflation were also found. The classical features of C. pneumoniae as hilar and perihilar infiltrates and reticular parenchymal infiltrates were not found in our study. Thus, X-rays were not found to be much specific for Chlamydial etiology.

Overall among the various clinical and laboratory parameters studied, significant association with disease etiology was seen with prolonged and distressing cough, and increased absolute eosinophil count in blood.

DISCUSSION

Etiology of pneumonia in early infancy is not well described in developing countries, although a number of investigations have focused on later infancy and preschool years. C. trachomatis is responsible for about one-third cases of atypical pneumonia in infants up to 6 months of age.

ELISA test was used to detect the serum IgM antibodies against C. trachomatis. This test is a simple and reliable test, which gives rapid results.

This study showed that seroprevalence of C. trachomatis in infants of up to 6 months of age having lower respiratory tract infection with features of atypical pneumonia was 24%.

Close to the results of this study was a study conducted by Muhe et al. in Ethiopia (1999), in which they reported C. trachomatis in 15.8% infants younger than 3 months of age, who had pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis.[7] In another study conducted at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, India, by Kabra et al., to identify pathogens responsible for ALRI in under 5 children (mean age 11.2 months), they found the seroprevalence of C. trachomatis to be 11%.[12] Wubbel et al. (USA) in 1999 found the seroprevalence of Chlamydia to be 6% in 6 months to 6 years ambulatory children.[13] The low prevalence rate in these studies compared to our study can be attributed to older age group of the study sample and acute symptoms taken in these studies.

This study was conducted at Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College, which comes under Bundelkhand region. Bundelkhand is an area where most of the people are in low socioeconomic group and maternal infection with C. trachomatis is more in this socioeconomic group of patients. Thus, in infants of this area, when taken up to 6 months of age with features of atypical pneumonia, the prevalence rate of C. trachomatis was found to be more. Nonetheless, all these studies show that Chlamydia is an important cause of lower respiratory tract infection with symptoms of atypical pneumonia in children, and it is not a rare cause as previously thought.

On analysis of the prevalence of C. trachomatis in different age groups, we found that 8 (75%) of cases with lower respiratory tract infections positive for C. trachomatis were of below 4 months of age.

Colarizi et al. found in their study that C. trachomatis was also detected within 24 h of life, from preterm infants born by cesarean section without premature rupture of membranes.[8] In a study conducted by Pao et al., they detected C. trachomatis DNA sequences in the amniotic fluid of a substantial proportion of women with uro-genital Chlamydia infection, thus suggesting an in-utero mechanism by which Chlamydia can be transmitted before birth.[14] Thus, while infants born by vaginal route have more chances of Chlamydial infection, infants born by cesarean section are also at risk of getting this infection.

In our study infants having cough of more than 1 week duration were more likely to be ELISA positive for C. trachomatis and it was found to be statistically significant (Fisher's exact test value 0.024). Margaret et al., in their study, found that 59% of Chlamydia positive infants had paroxysm of staccato coughing.[15] Schacter found that distinctive cough was present in many of infants with this type of pneumonia.[16] Beem and Saxon found that a distinctive cough was an important finding in infants having pneumonia due to C. trachomatis.[17] Cough usually occurs as staccato paroxysms that may be followed by periods of vomiting or apnea. Thus, prolonged and distressing cough can give an important clue for the clinical diagnosis of C. trachomatis in these infants.

In our study, out of 12 infants positive for C. trachomatis, 7 (58%) had fever while 5 (42%) did not have fever. This association was not found to be statistically significant (Fisher's exact test value 0.06). The present finding in the study may be because of the fact that infection with C. trachomatis is of low virulence and usually fever is absent in this infection. Schacter et al. in 1978 also found that this pneumonia is characterized by an afebrile course.[16] Salaria and Singh found that in spite of extensive pneumonia, the infant almost always remains afebrile.[18]

An important observation which we found in our study was that positivity of infants for C. trachomatis was more in those having absolute eosinophil count more than 300 per cu mm. A total of 35.7% of cases with absolute eosinophil count more than 300 per cu mm were positive for C. trachomatis whereas only 9.09% cases with absolute eosinophil count less than or equal to 300 per cu mm were positive for C. trachomatis. In our study, 83% of total cases positive for C. trachomatis had absolute eosinophil count more than 300 per cu mm. By application of χ2 test, this association was found to be significant. Margaret et al. found in their study that absolute eosinophil count values were commonly elevated in these infants.[15] A total of 71% of total positive infants had count more than or equal to 300 per cu mm. According to Salaria and Singh blood examination in these children often shows absolute eosinophilia.[18] The eosinophilia found in these infants positive for C. trachomatis could be due to allergic response from C. infection, thus eosinophilia is an important associated finding in infants of lower respiratory tract infection positive for C. trachomatis.

We found in our study that infants positive for C. trachomatis had variable findings on chest X-ray. Most common finding was of patchy infiltrates. Besides that minimal infiltrates and hyperinflation were also found in the chest X-rays. The classical picture of C pneumoniae of hilar and perihilar infiltrates and reticular parenchymal infiltrates was not found in our study. Hence, X-rays were not found to be of much significance for Chlamydial etiology.

Limitations of study

The study used ELISA for establishing the diagnosis of C. trachomatis instead of the gold standard. As the sample size of the study was 50, similar study on larger sample size should be planned for generalizing the results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Department of Microbiology, MLB Medical College, Jhansi, for conducting ELISA test.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children? Lancet. 2005;365:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulholland K. Global burden of acute respiratory infections in children: Implications for interventions. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:469–74. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shann F, Woolcock A, Black R, Cripps A, Foy H, Harris M, et al. Introduction: Acute respiratory tract infection - the forgotten pandemic. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:189–91. doi: 10.1086/515107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams JV, Harris PA, Tollefson SJ, Halburnt-Rush LL, Pingsterhaus JM, Edwards KM, et al. Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise healthy infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:443–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo CC, Jackson LA, Campbell LA, Grayston JT. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:451–61. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn DL, Dodge RW, Golubjatnikov R. Association of Chlamydia pneumoniae (strain TWAR) infection with wheezing, asthmatic bronchitis and adult onset asthma. JAMA. 1991;266:225–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhe L, Tilahun M, Lulseges S, Kebede S, Enaro D, Ringertz S, et al. Etiology of pneu-monia, sepsis and meningitis in infants younger than three months of age in Ethiopia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:S56–61. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199910001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colarizi P, Chiesa C, Pacificol L, Adorisio E, Rossi N, Ranucci A, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis associated respiratory disease in the very early neonatal period. Acta Pediatr. 1996;85:991–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Principi N, Esposito S. Comparative tolerability of erythromycin and newer macrolide antibacterials in pediatric patients. Drug Saf. 1999;20:25–41. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199920010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni AP, Lin GY, Yang L, He HY, Huang CW, Liu ZZ, et al. A seroepidemiologic study of Chlamydia pneumoniae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia psittaci in different populations on the mainland of China. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:553–7. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel Rahman MM, Abdel Dayem SI, Eid SA, Badie OA, Kotb NA. Immunofluorescent diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the respiratory tract and eye. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1993;23:656–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabra SK, Lodha R, Broor S, Chaudhary R, Ghosh M, Maitreyi RS. Etiology of acute lower respiratory tract infection. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:33–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02722742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wubbel L, Muniz L, Ahmed A, Trujillo M, Carubelli C, McCoig C, et al. Etiology and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in ambulatory children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:98–104. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pao CC, Kao SM, Wang HC, Lee CC. Intraamniotic detection of Chlamydia trachomatis deoxyribonucleic acid sequences by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1295–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90702-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipple MA, Beem MO, Saxon EM. Clinical characteristics of the afebrile pneumonia associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection in infants less than 6 months of age. Pediatrics. 1979;63:192–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schacter J. Chlamydia infection. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:540–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803092981005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beem MO, Saxon EM. Respiratory tract colonization and a distinctive pneumonia syndrome in infants infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:306–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197702102960604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salaria M, Singh M. Atypical pneumonia in children. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]