Abstract

Background:

The association of the present Chikungunya pandemic with a mutation in the Chik virus is already established in many parts of the world, including Kerala. Kerala was one of the worst-affected states of India in the Chikungunya epidemic of 2006–2007. It is important to discuss the clinical features of patients affected by Chikungunya fever in the context of this change in the epidemiology of the disease.

Aim:

This study tries to analyze the clinical picture of the Chikungunya patients in Kerala during the epidemic of 2007.

Setting and Design:

A cross-sectional survey was carried out in five of the most affected districts in Kerala, India.

Materials and Methods:

A two-stage cluster sampling technique was used to collect the information. Ten clusters each were selected from all the five districts, and the size of the clusters were 18 houses each. A structured interview schedule was used for data collection. Diagnosis based on clinical signs and symptoms was the major case-finding strategy.

Results and Conclusion:

Of the 3623 residents in the surveyed households, 1913 (52.8%) had Chikungunya clinically. Most of the affected were in the adult age group (73.4%). Swelling of the joints was seen in 69.9% of the patients, followed by headache (64.1%) and itching (50.3%). The knee joint was the most common joint affected (52%). The number of patients with persistence of any of the symptoms even after 1 month of illness was 1388 (72.6%). Taking bed rest till the relief of joint pain was found to be a protective factor for the persistence of the symptoms. Recurrence of symptoms with a period of disease-free interval was complained by 669 (35.0%) people. Older age (>40 years), a presentation of high-grade fever with shivering, involvement of the small joints of the hand, presence of rashes or joint swelling during the first week of fever and fever lasting for more than 1 week were the significant risk factors for recurrence of symptoms predicted by a binary logistic regression model. In conclusion, we found that there is substantial acute and chronic morbidity associated with the Chikungunya epidemic of 2007.

Keywords: Chikungunya, Clinical feature, Epidemic, India, Kerala

INTRODUCTION

Chikungunya is described as an acute illness, with fever, skin rash and incapacitating arthralgia.[1] Arthralgia is the salient feature of Chikungunya that distinguishes it from Dengue, which otherwise shares the same vectors, symptoms and geographical distribution.[2] The disease itself is rarely fatal[3] and is sometimes confused with Dengue, O’nyong-nyong or Sindbis virus infection.[4] Typical features of the disease include abrupt, massive outbreaks with a high attack rate[5,6] followed by slow decline of cases as herd immunity develops.[7–9]

In India, the first Chikungunya outbreak was recorded in Calcutta in1963,[10] followed by multiple epidemics in different parts of the country till 1973.[11–13] Because of its long absence since 1973, it was postulated that the Chikungunya virus had disappeared from the Indian subcontinent and from South-East Asia.[14,15] However, the epidemic resurfaced in December 2005,[16] with several states reporting massive outbreaks during the period 2005–2006. Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines[17–20] also experienced a re-emergence of Chikungunya. Kerala, the southern state of India, was heavily affected by the pandemic during 2006–2007. The viruses isolated in Kerala in the latter part of 2007 were shown to have undergone an A226V mutation.[21] It was postulated that this mutation was associated with the increased virulence of Chikungunya in reunion islands[22,23] and in the Indian subcontinent.[24]

The clinical onset of Chikungunya is abrupt, with high fever, headache, back pain, myalgia and arthralgia after a short incubation period of 2–4 days.[25] The symptoms generally resolve within 7–10 days, except for joint stiffness and pain. Fever and arthralgia have been reported in all patients with Chikungunya in the epidemics reported recently in India and in the reunion islands.[26–28] Erratic, relapsing and incapacitating arthralgia is the hallmark of Chikungunya, affecting the extremities (ankles, wrists, phalanges) mainly but targeting the large joints as well.[25–28] Joints appear normal radiologically, and the biological markers of inflammation are either normal or moderately elevated.[29,30] There are a few precise descriptions of Chikungunya virus-associated joint disorders, and the underlying mechanism is unknown.[29,30] Skin involvement is present in a significant number of cases, and consists of maculopapular rash, facial edema, bullous eruptions with pronounced sloughing, localized petechiae and bleeding gums (mainly in children).[25–27]

The association of the present Chikungunya pandemic with a mutation in the Chik virus is already established in many parts of the world, including Kerala.[21,22] But, the extent of contribution of this mutation to the epidemiology of this Chikungunya outbreak is an issue of debate. This study tries to analyze the clinical picture of the Chikungunya patients in Kerala in the backdrop of the possible presence of the virulent type of virus (A226V mutation).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional survey was conducted during October–November, 2007, in the five districts of Kerala, namely Kollam, Alappuzha, Kottayam, Pathanamthitta and Idukki. These five districts were among the worst hit during the 2007 epidemic. A two-stage sampling technique was used to collect the information. From each district, 10 panchayaths (jurisdiction of Local Self Governments) were selected at random (Lot method). A cluster consisting of 18 houses from each panchayath was selected for the study. The area most heavily affected with Chikungunya fever was found out with the help of the heads of the panchayaths and primary health centers (the Department of Health under the jurisdiction of Local Self Governments). From the area, the first house was selected arbitrarily and the next 17 houses were selected serially based on the distance shortest from the previous house.

The case definition of Chikungunya used for including patients in the study was “an attack of joint pain affecting more than one joint with appearance of fever within a period of two days prior to and two days after the onset of joint pain.” The information about the infants and children was collected from their mothers. The inclusion of patients using a clinical case definition was carried out because of resource constraints. But, the predictive power of clinical diagnosis will be high during an epidemic because of an increased background prevalence of the disease. A study conducted by a multidisciplinary team from Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, revealed that the positive predictive value of this case definition was as high as 82% during the epidemic when compared with IgM ELISA for Chikungunya.

A structured interview schedule was used for data collection. The tool was prepared by a group comprising of epidemiologists, entomologists and sociologists. The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed qualitatively with the help of entomologists, sociologists and epidemiologists in the Department of Community Medicine and the faculty of the Clinical Epidemiology Unit of Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

The data collection was carried out by household visits and by interviewing the patients. The data were collected by volunteers of the Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP) who were trained in administering the questionnaire, selection of clusters and interview techniques. The KSSP volunteers were asked to collect information from 180 houses in each district (an overall sample size of 900). When the patients were not available during the house visit, the information was collected from their family members. The medical records of the patients were also used to ensure the consistency of the data. The questionnaires were collected back after verifying all the entries.

Ethics

The study protocol was submitted to the ethical committee of the KSSP and ethical approval was obtained. The study was carried out in consultation with the local Panchayath heads. The written informed consent of the head of the family was obtained before the commencement of the interview. Consent was obtained from the patient if he/she was available at the time of the interview. Information was collected from children below 12 years of age with the consents of the parents.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and proportions were used to interpret the data. Chi-square test and t-test were used to interpret the statistical significance of associations and Odd's ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence interval (CI) was used to estimate the strength of association between the dichotomous variables. Adjusted OR with 95% CI for the risk factors of recurrence of Chikungunya was obtained by logistic regression.

RESULTS

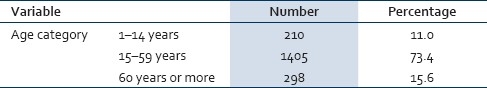

Of the total 900 households from which information was collected, 43 (4.8%) were excluded from the final analysis as the data were incomplete. In the 857 households included in the study, there were 3623 members, with the average family size being 4.23 persons. The number of people affected with Chikungunya fever as per the case definition was 1913 (52.8%). Mean age standard deviation of these patients was 40.25 (18.76) years. Women constituted (50.6%) 969 of these patients. The age distribution of the affected people is shown in Table 1. Most of the affected were in the adult age group (73.4%), and 11% of the cases occurred in persons <15 years of age.

Table 1.

Age distribution of the affected subjects

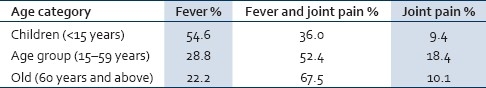

Fifty-two percent of the patients reported fever along with joint pain as the initial symptom. Fever alone (without joint pain) and joint pain alone (without fever) were seen as the initial symptoms in 31.1% and 16.9% of the patients, respectively. Patients having fever alone as the initial symptom were younger (t=6.48, df=1911, P< 0.001) compared with those presenting initially with joint pain alone. The distribution of the first symptom against age is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

First appearance of symptoms with respect to the age categories

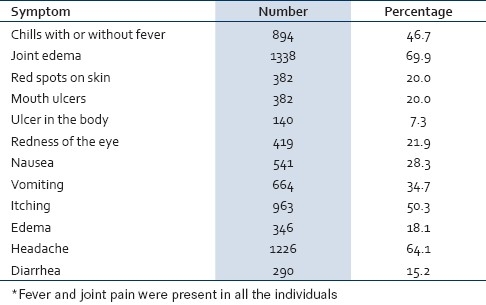

Major symptoms during the first week of the disease are presented in Table 3. Fever and joint pain were seen in all the patients included in the study because these were a part of the case definition. Swelling of joints was seen in 69.9% of the patients, being closely followed by head ache (64.1%) and itching (50.3%). The distribution of symptoms was not significantly different across the gender groups. Persistence of joint pain even after the first week of illness was present in 74.8% of the males and in 70.5% of the females. This difference was found to be statistically significant (P=0.035).

Table 3.

Major symptoms in the first week of illness*

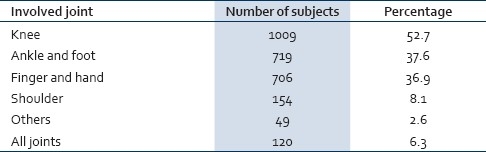

More than 52% of the subjects had involvement of the knee joints, while 8.1% had shoulder joint involvement. The frequency of different joint involvement is shown in Table 4. Shoulder joint was affected in 9.7% of the women compared with 6.4% among the men (P=0.007). There is no significant gender difference in the case of the other joints.

Table 4.

Pattern of joint involvement

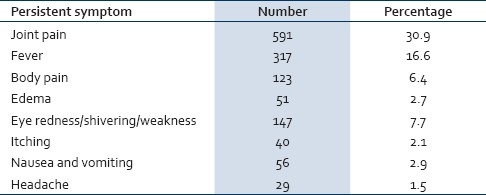

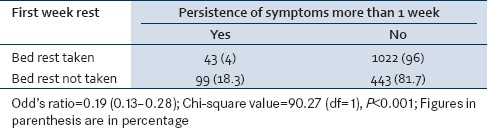

The number of patients with persistence of any of the symptoms even after 1 month of illness was 1388 (72.6%). Persistence of a symptom means that there is no disease-free interval during a period of 1 month from the appearance of the first symptom. Common persistent symptoms after 1 month of illness are shown in Table 5. The persistence of symptoms was an unusual presentation in case of children. Children often presented with fever without joint pain [Table 2], and the joint pain developed was not persistent. Taking bed rest till the joint pain subsided was found to be a protective factor (OR [95% CI=0.19 [0.13–0.28]], P<0.001) from the persistence of the symptoms [Table 6]. People already having any debilitating illness that hindered their ambulation were excluded from this analysis. The data of preschool children (<5 years) were also not included because the interviewers could not document their daily activities, including the hours spent in bed.

Table 5.

Persistent symptoms

Table 6.

Taking rest and persistence of symptoms

Recurrence of symptoms with a period of disease-free interval was complained by 669 (35.0%) people. According to the binary logistic regression, those people with age more than 40 years, those who presented with fever associated with shivering, rashes or joint swelling in the first week of the illness, those who had fever that did not subside within 1 week and those with small joints of hands affected by the illness were found to be prone for recurrence of symptoms [Table 7].

Table 7.

Significant determinants for recurrence of Chikungunya fever

DISCUSSION

It is well documented that the environmental factors of Kerala are still favoring an outbreak of arboviral disease.[31] Because of the lack of specific symptoms, often, Chikungunya infection cannot be differentiated from Dengue fever or Leptospirosis.[32] This study tried to identify the key clinical features and sociodemographic profile of patients affected with Chikungunya in Kerala, South India, along with factors associated with recurrence. The majority of the patients in this study were in the 15–59 year age group. Only 11% of the cases were children below 15 years, which is very low compared with the population proportion (21.4%).[32] More than 15% of the affected people were elderly, with an age of 60 years or above, but the population proportion of this age group is 11%.[33] This difference in the clinical spectrum with respect to the age group has been documented in other studies also.[34] The causal mechanism of this age shift may be immunological or sociocultural. Factors including occupation and clothing habits may have an influence on the disease pattern. The age and gender profile of cases was similar to that reported in other epidemics in India[25,33] and reunion islands.[26] Nearly 2/3rd of the patients were found to spend most of their time indoors – either in their home or workplace – during the daytime. This pattern could be explained by the fact that the breeding places of Aedes mosquitoes are either domestic or peridomestic, and that the flight ranges of these mosquitoes are short.[35]

Unlike many other reported epidemics of Chikungunya in India and in the reunion islands,[25–27] the current study found that fever was the most common initial symptom among children <15 years of age. As age increased, more people presented with joint involvement as the initial symptom. Among the >60 years age category, 77% had joint involvement as the first symptom. Swelling of the joints was very high (69.3%) compared with other epidemics in India.[25,33] The percentage of Chikungunya patients reporting rashes in the current study was similar to those of other Indian epidemics,[23] while it was lower compared with the epidemics in reunion island.[24,27] Headache, vomiting and diarrhea were seen in a higher proportion compared with other epidemics.[22–27] Ulcers in the mouth (20%) or in the body (7.3%) were present in a significant fraction. Approximately 22% of the patients had redness of the eye, which makes Leptospirosis a common differential diagnosis. Unlike the previous reports, 50.3% of the Chikungunya patients in our study reported itching as a predominant symptom in the first week of illness.

Nearly 3/4th of the subjects had recurrence of symptoms after at least 1 week of symptom-free interval thus contributing to the morbidity burden. Prolonged arthralgia was noted in other studies also.[34] Incapacitating joint involvement is considered to be the main culprit contributing to the chronic morbidity associated with Chikungunya.

Limitations of the study

The sampling technique used in this study is a two-stage cluster sampling. But, this may not be the appropriate sampling technique for this study since Chikungunya is a communicable disease that tends to cluster and, thereby, affect the estimation of prevalence. The cases had been included in the study based on a purely clinical definition and confirmation using IgM ELISA was not performed. Information collected could be incomplete because the subjects might have forgotten some details of the disease. This was minimized by correlating the history of the patients with the clinical case records. The case definition may have induced some underreporting of symptoms and signs in case of infants and children. The study includes only cases having newly developed joint pain and fever (case definition), which excludes the preexisting joint pain. But, other co-morbidities like diabetes and their impact on the symptomatic outcome were not quantified in the present study.

The volunteers were advised to collect information either directly from the patients or from the family member if the patient was not available physically. And, they were advised to triangulate the data with the help of medical records. The information collected from the surrogates may have contributed some bias.

CONCLUSION

We found that there is substantial acute and chronic morbidity associated with the present Chikungunya epidemic. It has affected more than half of the population in the epidemic-hit areas. The proportion of patients with persistence of any of the symptoms even after 1 month of illness was 72.6%. Taking bed rest till the joint pain subsided was found to be a protective factor from the persistence of the symptoms. Recurrence of symptoms with a period of disease-free interval was complained by 35% of the people. According to the binary logistic regression, those people with age more than 40 years, those who presented with fever associated with shivering, rashes or joint swelling in the first week of the illness, those who had fever that did not subside within a week and those with small joints of the hands affected by the illness were found to be prone for recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the help rendered by Dr. S. Remadevi, Professor of Medical Sociology and Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram and Dr. P. B. Jayageetha, Assistant Professor, Biostatistics, Department of Community Medicine, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, for their valuable help in preparing the tool and in the statistical analysis. We would like to express our gratitude to the volunteers of the KSSP.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey DE. Chikungunya and dengue: A case of mistaken identity? J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1971;26:243–62. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/xxvi.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields’ Virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harley D, Sleigh A, Ritchie S. Ross River virus transmission, infection, and disease: A cross-disciplinary review. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:909–32. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.909-932.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers AM, Brault AC, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Re-emergence of chikungunya and o’nyong-nyong viruses: Evidence for distinct geographical lineages and distant evolutionary relationships. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:471–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padbidri VS, Gnaneswar TT. Epidemiological investigations of chikungunya epidemic at Barsi, Maharashtra state, India. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1979;23:445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laras K, Sukri NC, Larasati RP, Bangs MJ, Kosim R, Djauzi, et al. Tracking the re-emergence of epidemic chikungunya virus in Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:128–41. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackenzie JS, Chua KB, Daniels PW, Eaton BT, Field HE, Hall RA, et al. Emerging viral diseases of southeast Asia and the western Pacific. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:497–504. doi: 10.3201/eid0707.017703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenzie JS, Smith DW. Mosquito-borne viruses and epidemic polyarthritis. Med J Aust. 1996;164:90–3. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb101357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah KV, Gibbs CJ, Banerjee G. Virological investigation of the epidemic of haemorrhagic fever in Calcutta: Isolation of three strains of Chikungunya virus. Indian J Med Res. 1964;52:676–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao TR. Recent epidemics caused by Chikungunya virus in India, 1963–1965. Sci Cult. 1966;32:215–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigues FM, Patankar MR, Banerjee K, Bhatt PN, Goverdhan MK, Pavri KM, et al. Etiology of the 1965 epidemic of febrile illness in Nagpur city, Maharashtra State, India. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46:173–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mourya DT, Thakare JP, Gokhale MD, Powers AM, Hundekar SL, Jaykumar PC, et al. Isolation of Chikungunya virus from aedes aegypti mosquitoes collected in the town of Yawat, Pune district, Maharashtra state, India. Acta Virol. 2001;45:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavri KM. Disappearance of Chikungunya virus from India and South East Asia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:491. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neogi DK, Bhattacharya N, Mukherjee KK, Chakraborty MS, Banerjee P, Mitra K, et al. Serosurvey of chikungunya antibody in Calcutta metropolis. J Commun Dis. 1995;27:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yergolkar PN, Tandale BV, Arankalle VA, Sathe PS, Sudeep A, Gandhe SS, et al. Chikungunya outbreaks caused by African genotype, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1580–3. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukunaga T, Rojanasuphot S, Pisuthipornkul S, Wungkorbkiat S, Thammanichanon A. Seroepidemiologic study of arbovirus infections in the north-east and south of Thailand. Biken J. 1974;17:169–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thaikruea L, Charearnsook O, Reanphumkarnkit S, Dissomboon P, Phonjan R, Ratchbud S, et al. Chikungunya in Thailand: A re-emerging disease? Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28:359–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter KR, Tan R, Istary Y, Suharyono W, Sutaryo, Widjaja S, et al. A serological study of chikungunya virus transmission in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Evidence for the first outbreak since 1982. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:408–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam SK, Chua KB, Hooi PS, Rahimah MA, Kumari S, Tharmaratnam M, et al. Chikungunya infection–an emerging disease in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:447–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar PN, Joseph R, Kamaraj T, Jambulingam P. A226V mutation in virus during the 2007 chikungunya outbreak in Kerala, India. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1945–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, et al. Genome microevolution of Chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vazeille M, Moutailler S, Coudrier D, Rousseaux C, Khun H, Huerre M, et al. Two Chikungunya isolates from the outbreak of la Reunion (Indian Ocean) exhibit different patterns of infection in the mosquito Aedes albopictus. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santosch SR, Dash PK, Parida MM, Khan M, Tiwari M, Rao Lakshmana PV. Comparative full genome analysis revealed E1: A226V shift in 2007 Indian Chikungunya virus isolates. Virus Res. 2008;135:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakshmi V, Neeraja M, Subbalaxmi MV, Parida MM, Dash PK, Santosh SR. Clinical features and molecular diagnosis of chikungunya fever from South India. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1436–42. doi: 10.1086/529444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pialoux G, Gaüzère BA, Jauréguiberry S, Strobel M. Chikungunya, an epidemic arbovirosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:319–27. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pialoux G, Gaüzère BA, Strobel M. Chikungunya virus infection: Review through an epidemic. Med Mal Infect. 2006;36:253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brighton SW, Prozesky OW, de la Harpe AL. Chikungunya virus infection: A retrospective study of 107 cases. S Afr Med J. 1983;63:313–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy AC, Fleming J, Solomon L. Chikungunya viral arthropathy: A clinical description. J Rheumatol. 1980;7:231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeandel P, Josse R, Durand JP. Exotic viral arthritis: Role of alphavirus. Med Trop. 2004;64:81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vijayakumar K, Anish TS, Sreekala KN, Ramachandran R, Philip RR. Environmental factors of households in five districts of Kerala affected by the epidemic of Chikungunya fever in 2007. Natl Med J India. 2010;23:82–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jupp PG, McIntosh BM. Chikungunya virus disease. In: Monath TP, editor. The arboviruses: Epidemiology and ecology. BocaRaton, FL: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 137–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aravindan KP. Keralan engane chinthikkunnu? 1st ed. Kozhikode, India: Kerala Sastra Sahithya Parishad; 2006. Keralapadanam: Keralam engane jeevikkunnu? [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kannan M, Rajendran R, Sunish IP, Balasubramaniam R, Arunachalam N, Paramasivan R, et al. A study on chikungunya outbreak during 2007 in Kerala, South India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:311–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrington LC, Scott TW, Lerdthusnee K, Coleman RC, Costero A, Clark GG, et al. Dispersal of Dengue vector Aedes aegypti within and between rural commuities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:209–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]