Abstract

Background:

Choroid plexus papilloma (CPP) is a benign neoplasm that arises from the ventricular choroid plexus. The clinical features, radiological characteristics, and treatment have been discussed in this study for a pediatric population.

Methods:

Over an eight-year period, seven pediatric (≤12 years) CPP patients were treated. Tumors were located in the lateral ventricle (n = 4), IVth ventricle (n = 2), and in both the lateral and IIIrd ventricles (n = 1). The patients presented predominantly with features of raised intracranial pressure. Total microsurgical excision was carried out in all cases.

Results:

There was complete relief of symptoms at follow-up in six patients. A 2.5 year-old child with a large trigonal CPP with hydrocephalus leading to complete visual impairment, died due to postoperative hypokalemia that caused ventricular fibrillation. One of our patients required a postoperative, permanent CSF diversion procedure while another required a subduroperitoneal shunt for persisting postoperative subdural CSF collection.

Conclusions:

Coagulation of the tumor under constant irrigation to shrink and excise it in toto, avoids excessive bleeding during surgery. The vascular pedicle supplying the tumor should be adequately dealt with during the last part of tumor removal as retraction of a bleeding pedicle may result in ventricular hemorrhage and brain edema. Following surgery, an external ventricular drain for three days helps in preventing the development of acute hydrocephalus in lateral ventricular lesions, and the color of the drained CSF gives an estimate of the ventricular hemostasis achieved. Total excision is usually possible in these cases with excellent postoperative outcomes.

Keywords: Choroid plexus, intraventricular tumor, tumor

Introduction

Choroid plexus papilloma (CPP) is an uncommon intracranial tumor of neuroepithelial origin. It constitutes about 3 and 0.5% of all intracranial tumors in children and adults respectively.[1] The common sites of these tumors are the lateral ventricles in children and the fourth ventricle in adults.[2,3] The cerebellopontine angle and the third ventricle are extremely rare sites for CPP.[4] Intraparenchymal locations of CPP have also been described. In this paper, we describe a series of seven cases of pediatric CPP and also discuss the clinical features, radiological characteristics, and treatment in the light of available literature.

Materials and Methods

Records of seven patients with choroid plexus papilloma managed at our institute were retrospectively reviewed for their radiological and histological findings [Table 1]

Table 1.

Summary of the seven patients with choroid plexus papilloma

Results

Clinical Findings

Out of the seven patients, two were male and five were female patients and their age ranged from two months to 12 years. Features of raised intracranial pressure in the form of headache, vomiting, progressive head enlargement, and excessive crying were present in all patients in varying combination. One patient had complete visual impairment due to secondary optic atrophy.

Radiological Findings

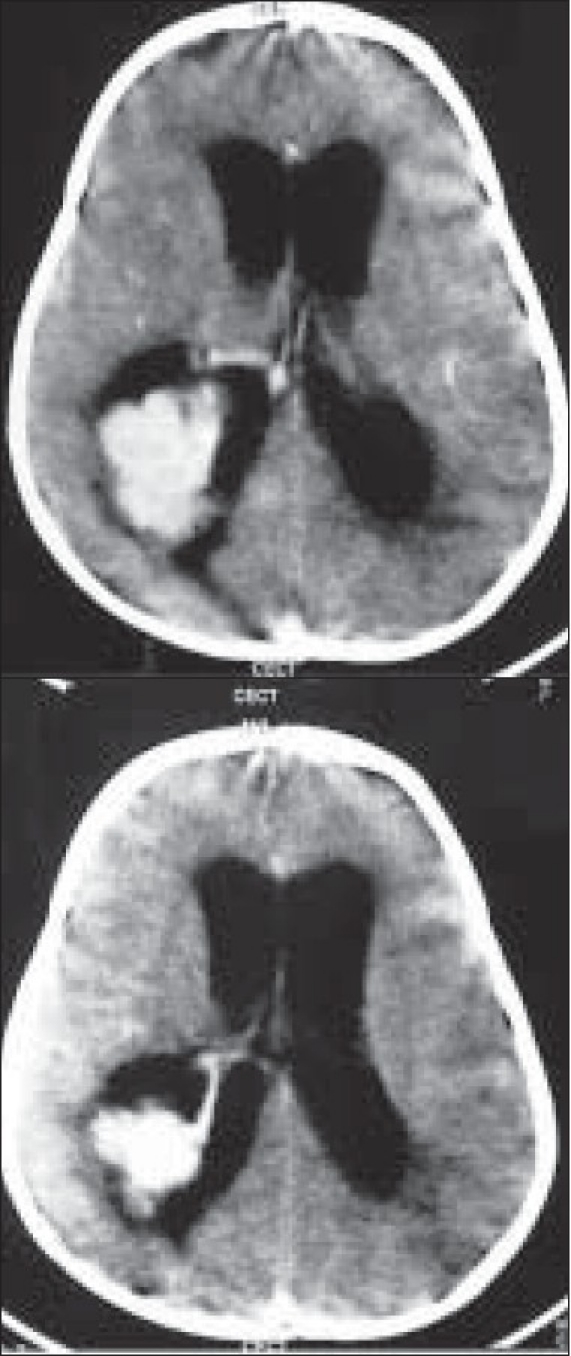

A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the head was performed preoperatively in all patients and an MRI was done in three of them. The tumor was located in the lateral ventricle (n = 4), IVth ventricle (n = 2), and in both the lateral and IIIrd ventricles (n = 1). The CT scans showed a brightly enhancing, lobulated, globular mass in the ventricle [Figures 1a–d]. Calcification was noted in five cases, while all the cases had varying degrees of hydrocephalus. A prominent vascular pedicle connecting the tumor with the choroid plexus was noted in four cases. MRI showed an enhancing mass in the ventricle which was isointense on T1- and hyperintense on T2-weighted images in all three cases where the radiological investigation was carried out.

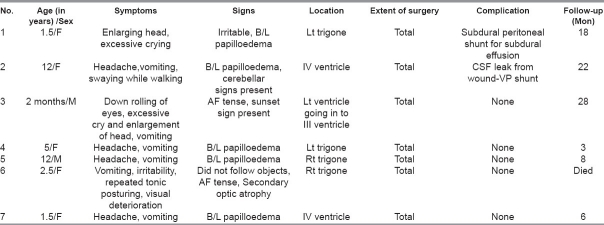

Figure 1a.

Axial CT scan in a 5 year-old child showing a trigonal choroid plexus papilloma with the typical frond-like appearance

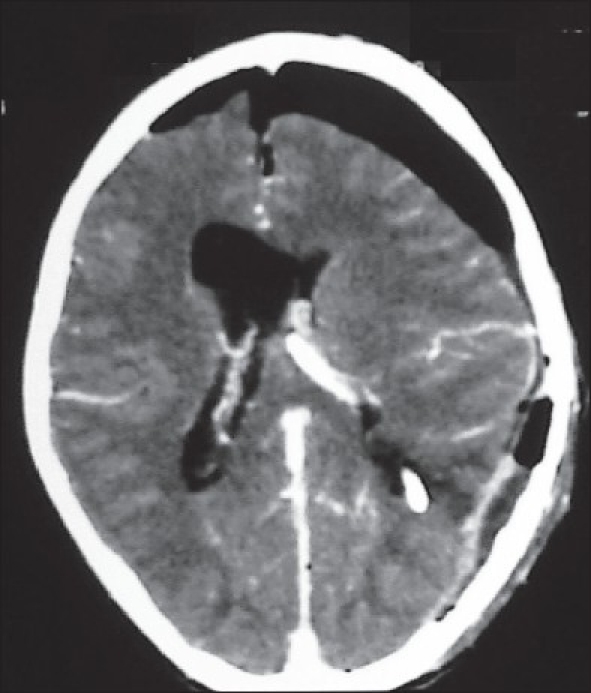

Figure 1d.

The postoperative image showing total excision of the lesion with resolution of the hydrocephalus

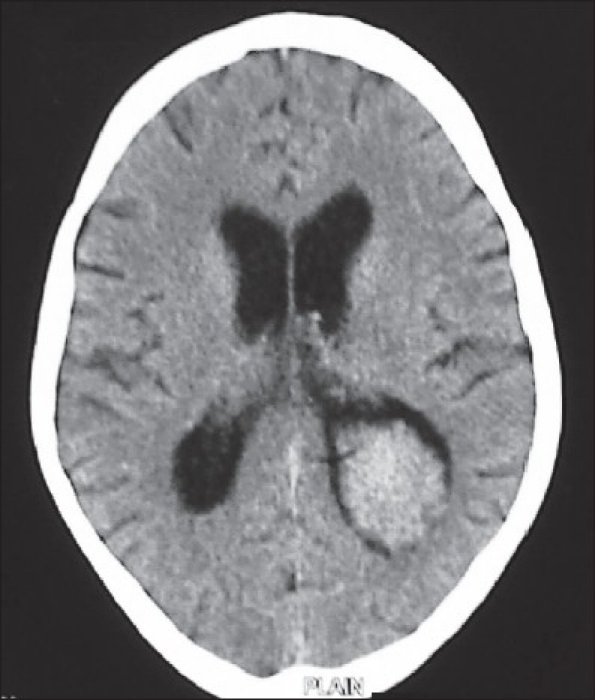

Figures 1b and c.

The contrast-enhanced image showing brilliant contrast enhancement of the tumor and the vascular pedicle. There is moderate hydrocephalus. The intraventricular location of the lesion is evident by the rim of CSF all around the tumor

Surgical Procedure

Total microsurgical excision was performed by the transcortical route through the middle temporal gyrus approach in the four patients where the tumor was located in the trigone of the lateral ventricle [Figures 2a–i, 3a–e]. A midline suboccipital craniectomy was done in two patients where the tumor was located in the IVth ventricle. The cisterna magna was opened and the tonsils were separated. The tumor was encountered and its surface coagulated. It was removed after shrinking it by coagulation and irrigation.

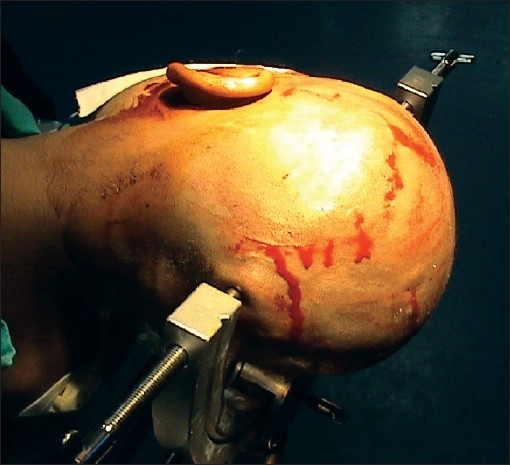

Figure 2a.

The patient's head position and skin incision for a posterior temporal craniotomy and middle temporal gyrus approach to the trigonal region

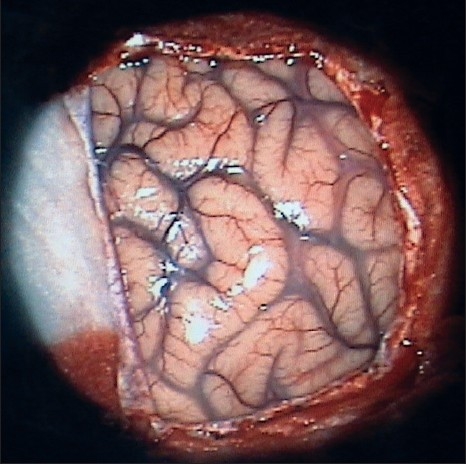

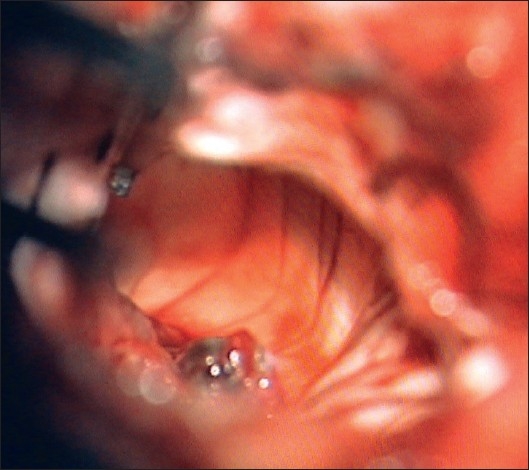

Figure 2i.

The temporal horn is clearly seen after tumor removal

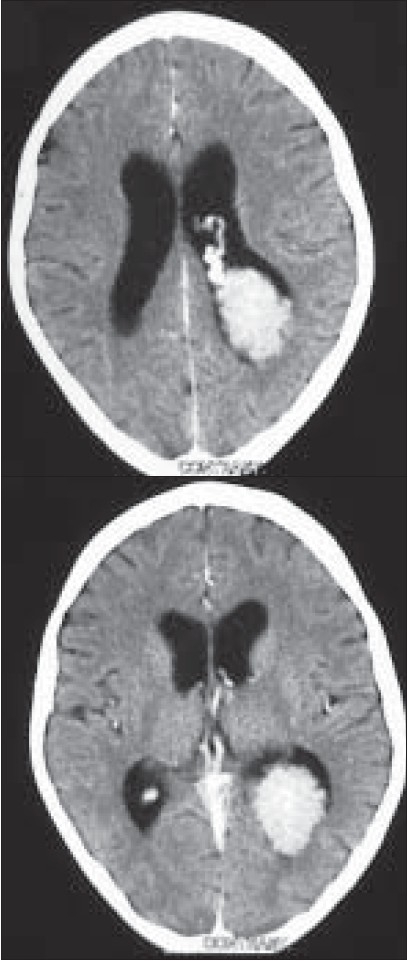

Figure 3a.

In a 2.5 year-old child, a large trigonal choroids plexus papilloma with ventricular CSF all around it and associated hydrocephalus

Figure 3e.

The postoperative scan showing excision of the lesion, resolution of the hydrocephalus, a small subdural collection, and a small clot at the operative site within the trigone

Figure 2b.

Following dural opening, the exposed temporo-occipital region

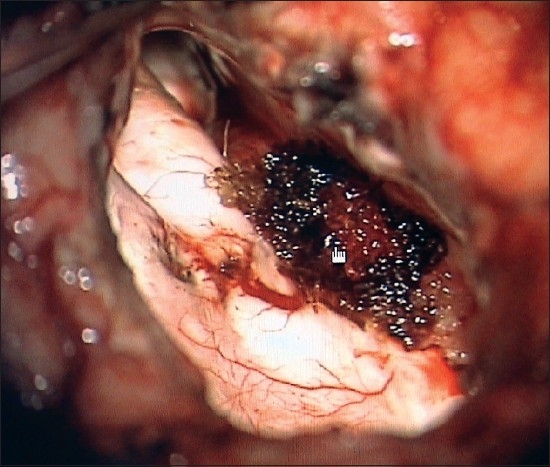

Figure 2c.

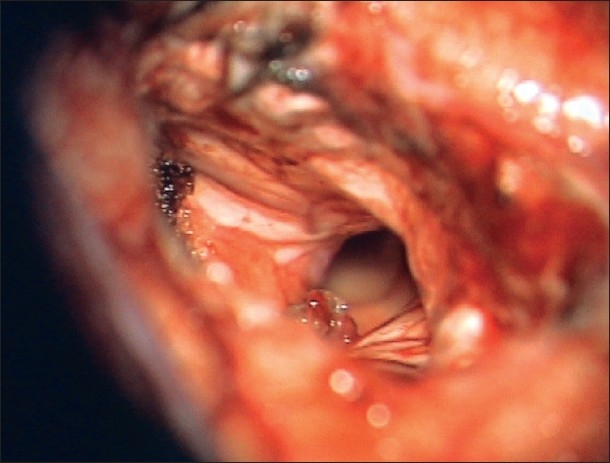

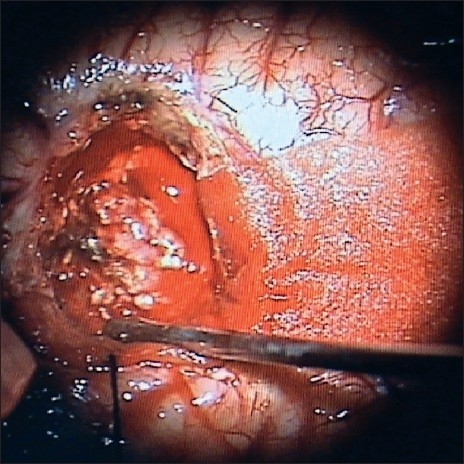

Once the CSF was drained from the ventricles by corticetomy through the middle temporal gyrus, the margins of the cortictomy fall apart exposing the reddish, mulberry-like tumor in the trigonal region

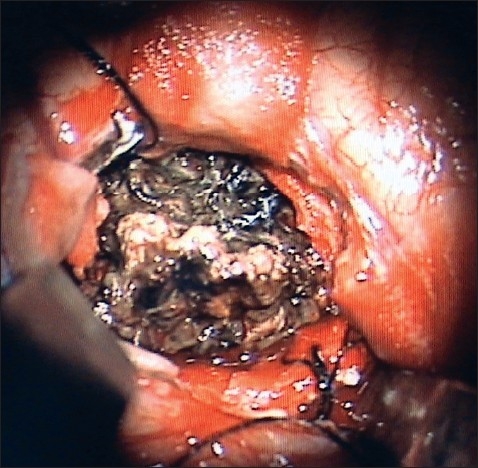

Figure 2d.

The exposed tumor is gently coagulated to shrink it

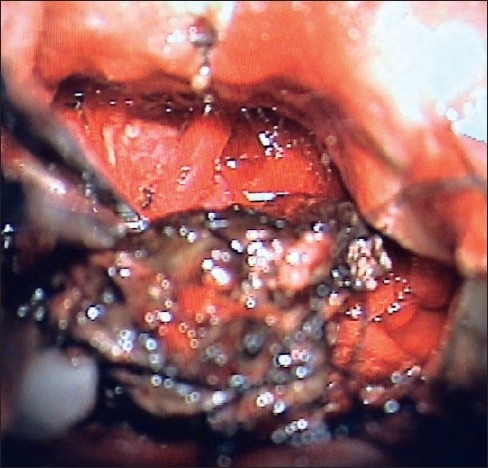

Figure 2e.

Once coagulated and shrunk, the tumor may easily be retracted from the smooth ventricular ependyma

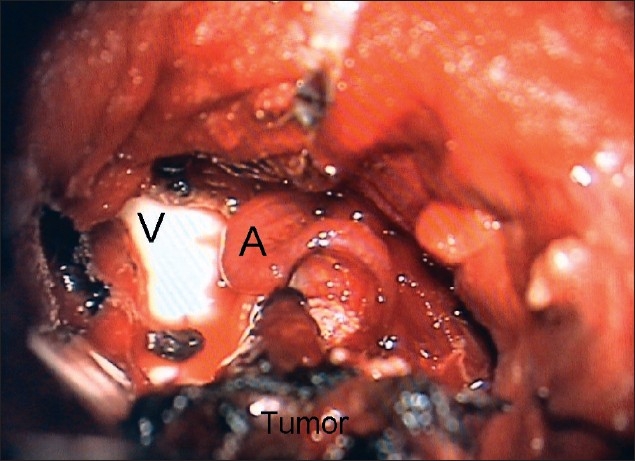

Figure 2f.

The vascular pedicle (A) supplying the tumor is clearly visible as the tumor is lifted off the ventricular surface (V). It is extremely important to coagulate and cut this pedicle. An avulsed vascular pedicle may cause profuse bleeding in the ventricles that may become difficult to control due to the consequent brain swelling

Figure 2g.

The trigone after removal of the tumor. The frontal horn is clearly seen

Figure 2h.

A surgicel is placed on the coagulated and divided tumor pedicle

Figures 3b and c.

The intense enhancement of the tumor and the vascular pedicle is clearly seen

The CSF pathway was established in all patients. One case had a postoperative CSF leak from the operative incision and required a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for persisting hydrocephalus. In a patient having both lateral and IIIrd ventricle tumor, an anterior interhemispheric, transcallosal approach was performed and total excision was achieved by accessing the third ventricle by the subchoroidal approach. The tumor was present both in the third and lateral ventricles due to its extension through the subchoroidal corridor superior to the thalamus. This patient developed a postoperative, subdural effusion which required a subduro-peritoneal shunt. A closed external ventricular drain was placed in all patients and allowed to drain CSF for three days. It was only removed once the hemorrhagic component in the CSF cleared and the postoperative CT scan ensured the absence of ventricular hematoma. One patient died the day following surgery due to persistent hypokalemia that led to refractory ventricular fibrillation. (Video clip can be seen on www.pediatricneurosciences.com

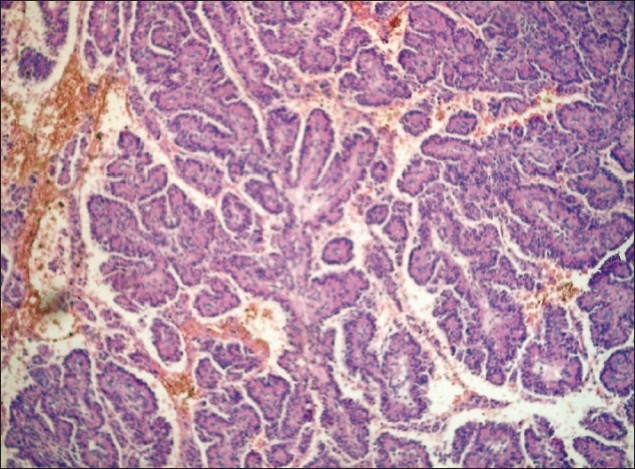

Histopathology

Histopathology results showed papillary structures with a delicate fibrovascular core lined by columnar or cuboidal epithelial cells with vesicular nuclei. No feature of malignancy was noted in any of these cases [Figure 3d].

Figure 3d.

Photomicrograph showing papillary structures with delicate fibrovascular core lined by columnar or cuboidal epithelial cells typical of CPP

Follow-Up

The follow-up available in six cases ranged from 3–28 months (mean: 12.8 months). All patients were symptom-free at follow-up with the postoperative CT scan showing no residual lesion. The contrast-enhanced CT scan, however, often showed a persistent and significantly greater enhancement of the ventricular choroid plexus on the side of the excised lesion.

Discussion

CPP is a slow-growing, benign neoplasm that arises from the choroid plexus epithelium. It constitutes about 3% and 0.5% of all intracranial tumors in children and adults respectively.[1] It usually occurs in the first and second decades of life, but has been reported in other age groups also. Only cases aged 12 years or less have been included in our study. CPP commonly occurs in the lateral ventricles in children, and in the fourth ventricle in adults; other uncommon sites are the third ventricle and the cerebellopontine angle. CPP has also been reported in the suprasellar region, cerebellum, and the frontal lobe.[3–5] In our study, the tumor was located in the lateral ventricle (four cases), IVth ventricle (two cases), and both the lateral and IIIrd ventricles (one case).

CPP predominately presents with features of raised intracranial pressure in the form of headache, vomiting, and visual deterioration. Progressive enlargement of the head and excessive crying are present in majority of the infants. Raised intracranial pressure is due to hydrocephalus as a result of obstruction of the CSF pathway, excessive production of CSF, and recurrent occult bleeding due to the tumor, leading to arachnoidal fibrosis and adhesions. One of our patients developed complete visual impairment as well as recurrent opisthotonic posturing despite open, but extremely tense, fontanelle, illustrating the need to avoid complacency and delay in the management of these benign tumors. It should, therefore, not be assumed that because the sutures and fontanelles are open in children, the sequele of raised intracranial pressure such as blindness (due to secondary optic atrophy) and opisthotonic posturing (due to central neuraxial herniation) will not manifest. Seizures and mental changes may often be the only clinical features in these lesions and fourth ventricular tumors may also have cerebellar signs. Cerebellopontine angle CPP has been reported to present with cranial nerve deficits.[2,3] The predominant clinical features in our study were due to raised intracranial pressure in all patients.

The classical CT findings of CPP have been described as a well-defined, homogeneously enhancing, lobulated mass with an irregular frond-like pattern, resulting in a cauliflower-like appearance typically seen in cases of intraventricular tumors. Fine, speckled calcification is often seen within the tumor. MRI may reveal hypo- or isointense lesion on T1WI and hyperintense lesion on T2WI with marked enhancement on contrast. Varying degrees of associated hydrocephalus is also present in almost all the cases.[6–8] Calcification was present in five patients in our study.

Grossly, choroid plexus papillomas appear as pink or reddish globular masses with a rough, irregular surface resembling a cauliflower. They are very vascular and sometimes, significant calcification is noted. Microscopically, they resemble the normal architecture of the choroid plexus and show papillae composed of a single layer of columnar or cuboidal epithelium lining a stroma of vascularized connective tissue. Features of microscopic invasion, mitotic activity, and pleomorphism should raise the possibility of malignancy, even when the general architecture indicates a well differentiated papilloma.[9] The histopathology results for all our cases were characteristic of CPP, with no evidence of malignancy.

The treatment of choice of CPP is surgical excision of the tumor. Total excision should be the aim and is usually achievable, as was seen in the present series. As the prevention of bleeding is a major consideration during surgical excision of these lesions in pediatric patients, gentle coagulation of the tumor under constant irrigation (to shrink the tumor and remove it in totality), is preferred to its piecemeal excision. In our series, cortical incision was made posterior to the vein of Labbe in the tumors situated in the trigone. This provided the shortest access to the trigone, prevented injury to the eloquent superior temporal gyrus in the left-sided lesions, and ensured that undue retraction of the vein of Labbe with its inherent risk of venous infarction did not occur. The retractors were only applied after the corticectomy achieved ventricular CSF drainage and the brain became lax. The brain retractors were placed mainly towards the inferior temporal gyrus of the corticetomy to avoid retracting the perisylvian area as well as the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle that is close to the genu and the posterior limb of the internal capsule. The thalamostriate vein was meticulously preserved in the lateral ventricle anterior to the tumor. The vascular pedicle supplying the tumor was coagulated and divided during the last part of tumor removal as retraction of a bleeding pedicle may result in profuse ventricular hemorrhage and brain edema. The consequent brain swelling may close the corticectomy edges and make the process of securing of the bleeding pedicle even more difficult. Hydrocephalus is generally relieved following excision of the tumor, but in some cases with persisting postoperative hydrocephalus (usually due to arachnoidal adhesions at the level of subarachnoid spaces and arachnoidal granulation leading to the communicating hydrocephalus), a permanent CSF diversion procedure may be required.[10] Postoperative radiation therapy is indicated in cases with incomplete excision although its validity is doubtful. Radiotherapy also has a role in cases where histopathology is suggestive of features of malignancy.[11] In our series, all patients underwent total tumor excision and none of them received radiotherapy.

Conclusions

CPP is an intraventricular tumor of childhood and may also occur in adults. Raised intracranial pressure is the most common clinical presentation. Coagulation of the tumor under constant irrigation shrinks the lesion away from the surrounding ventricular ependymal walls and avoids excessive bleeding during surgery. The vascular pedicle supplying the tumor should be adequately dealt with during the last part of tumor removal, as retraction of a bleeding pedicle may result in ventricular hemorrhage and brain edema. Following surgery, an external ventricular drain prevents the development of acute hydrocephalus in lateral ventricular lesions, and the color of the drained CSF gives an estimate of the ventricular hemostasis achieved. One must avoid complacency and delay in dealing with these lesions as devastating sequele of raised intracranial pressure—visual deterioaration and opisthotonic posturing, may occur despite sutural diastasis and open fontanelles. Total surgical excision is usually achievable with minimum morbidity and provides an excellent long-term outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Aguzzi A, Brandner S, Paulus W. Choroid plexus tumours. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee WK, editors. World Health Organisation classification of tumours, tumours of the nervous system. Lyons: IARC; 2000. pp. 84–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohm E, Strang R. Choroid plexus papillomas. J Neurosurg. 1961;18:493–500. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Jay V, Blaser S, et al. In: Choroid plexus papillomas and carcinomas in text book of neurological surgery. 4th ed. Youmans JR, editor. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1996. pp. 2542–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar R, Achari G, Benerji D, Jain VK, Chhabra DK. Choroid plexus papillomas of the cerebellopontine angle. Neurol India. 2002;50:352–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene RC. Extraventricular and intra-cerebellar papilloma of the choroid plexus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1951;10:204–7. doi: 10.1097/00005072-195104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovit RL, Schechter MM, Chodroff P. Choroid plexus papillomas.Observations on radiographic diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970;110:608–17. doi: 10.2214/ajr.110.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waluch V, Dyek P. Magnetic resonance imaging of the posterior fossa masses. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery update 1. New York: Mcgraw-Hill; 1990. pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girardot C, Boukobza M, Lamoureux JP, Sichez JP, Capelle L, Zouaoui A, et al. Choroid plexus papillomas of posterior fossa in adults, MR imaging and gadolinium enhancement. J Neuroradiol. 1990;117:303–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffin CM, Wick MR, Braun JT, Dehner LP. Choroid plexus neoplasms clinicopathological and immunohistochemical studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:394–404. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandy MJ, Ranjan A. Intraventricular tumors. In: Ramamurthy B, Tandon PN, editors. Text book of Neurosurgery. 2nd ed. New Delhi: BI Churchill Livingstone; 1996. pp. 930–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin VA, Steven LA, Gutin PH. In: Cancer principles and practices of oncology. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott Raven; 1997. Neoplasms of the central nervous system; pp. 2072–3. [Google Scholar]