SUMMARY

Responses of neurons in early visual cortex change little with training, and appear insufficient to account for perceptual learning. Behavioral performance, however, relies on population activity, and the accuracy of a population code is constrained by correlated noise among neurons. We tested whether training changes interneuronal correlations in the dorsal medial superior temporal area, which is involved in multisensory heading perception. Pairs of single units were recorded simultaneously in two groups of subjects: animals trained extensively in a heading discrimination task, and “naïve” animals that performed a passive fixation task. Correlated noise was significantly weaker in trained versus naïve animals, which might be expected to improve coding efficiency. However, we show that the observed uniform reduction in noise correlations leads to little change in population coding efficiency when all neurons are decoded. Thus, global changes in correlated noise among sensory neurons may be insufficient to account for perceptual learning.

INTRODUCTION

Perceptual learning enhances sensory perception and leads to improved behavioral performance (Goldstone, 1998), but the neural basis of this phenomenon remains incompletely understood. One hypothesis is that responses of sensory neurons are altered by learning to increase the information that is encoded. In this case, one would expect to observe neural correlates of increased sensitivity in early sensory areas. However, previous studies have found little or no change in the tuning properties of single neurons in early visual cortex, and it remains unclear whether these changes could account for perceptual learning (Chowdhury and DeAngelis, 2008; Crist et al., 2001; Ghose et al., 2002; Law and Gold, 2008; Raiguel et al., 2006; Schoups et al., 2001; Yang and Maunsell, 2004; Zohary et al., 1994a). Alternatively, perceptual learning may arise from changes in how sensory information is decoded and interpreted by higher brain areas (Dosher and Lu, 1999; Law and Gold, 2008; Li et al., 2004).

Most neurophysiological studies of perceptual learning focused on the activity of individual neurons; however, behavior arises from population activity. By pooling information from many cells, the noise inherent in responses of single neurons could be reduced, thus improving coding efficiency. Theorists have shown that the information capacity of a population code depends on the correlated noise among neurons (Abbott and Dayan, 1999; Averbeck et al., 2006; Oram et al., 1998; Sompolinsky et al., 2001; Wilke and Eurich, 2002). In general, correlated noise could either decrease or increase the information transmitted by a population of neurons, depending on how correlated noise varies with the similarity of tuning between neurons (‘signal correlations’; Averbeck et al., 2006; Oram et al., 1998; Wilke and Eurich, 2002). The impact of correlations could be strong when the relevant neuronal population is large (Bair et al., 2001; Shadlen et al., 1996; Smith and Kohn, 2008; Zohary et al., 1994b).

Whether perceptual learning improves population coding efficiency through changes in the correlated variability among sensory neurons remains unknown. Modest noise correlations have been measured in a number of cortical areas (V1: Bach and Kruger, 1986; Gutnisky and Dragoi, 2008; Poort and Roelfsema, 2009; Reich et al., 2001; Smith and Kohn, 2008) (but see Ecker et al., 2010) (V4: Cohen and Maunsell, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009) (IT: Gawne et al., 1996; Gawne and Richmond, 1993) (MT: Cohen and Newsome, 2008; Huang and Lisberger, 2009; Zohary et al., 1994b), but how these correlations differ between untrained and trained animals has not, to our knowledge, been tested.

To examine the effect of training on correlated noise, we simultaneously recorded pairs of single neurons in the dorsal medial superior temporal area (MSTd), a multisensory area thought to be involved in heading perception based on optic flow and vestibular signals (Angelaki et al., 2009; Britten, 2008). Correlated noise among pairs of neurons was examined in two groups of animals: one group (‘naïve’) was only trained to fixate; the other group (‘trained’) also learned to perform a fine heading discrimination task. Noise correlations were significantly weaker in trained than naive animals, whereas tuning curves, response variability, and discrimination thresholds of individual neurons were similar. Importantly, training reduced noise correlations uniformly, regardless of tuning similarity between pairs of neurons. As a result, if all neurons contribute equally to perception, this change in correlated noise is unlikely to account for improvements in perceptual sensitivity with training.

RESULTS

Noise correlations in area MSTd

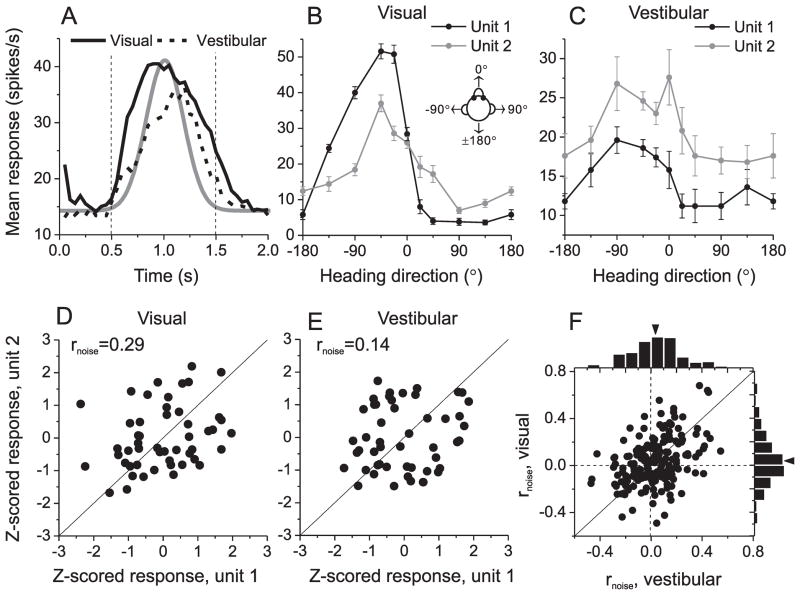

Monkeys were presented with two types of heading stimuli while maintaining fixation on a head-fixed target: inertial motion delivered by a motion platform in the absence of optic flow (vestibular condition) and optic flow stimuli presented while the animal was stationary (visual condition, see Methods for details). Consistent with previous findings (Gu et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2007), many MSTd neurons were tuned to heading direction, and their responses mainly followed the Gaussian velocity profile of the stimulus (Fig. 1A). We analyzed responses obtained during the middle 1 second of the stimulus period, during which neuronal activity was robust. Tuning curves of two simultaneously recorded cells are shown in Fig. 1B, C. The similarity of heading tuning between pairs of neurons was quantified as the Pearson correlation coefficient of mean responses across all stimulus directions (‘signal correlation’, rsignal). For this example pair of neurons, rsignal = 0.83 and 0.79 for the visual and vestibular conditions, respectively.

Figure 1.

Measuring noise correlation (rnoise) between pairs of single neurons in area MSTd. (A) Response time courses for populations of neurons with significant tuning (p<0.05, ANOVA) in the visual (solid curve, n=231) and vestibular (dashed curve, n=118) conditions. Gray curve represents the Gaussian velocity profile of the stimulus. Vertical dashed lines bound the time window over which spikes were counted for analysis. (B, C) Visual and vestibular heading tuning curves, respectively, for a pair of simultaneously recorded MSTd neurons (black and grey curves). Error bars: s.e.m. (D, E) Normalized responses from the same two neurons were weakly correlated across trials during visual (D) and vestibular (E) stimulation, with noise correlation values of 0.29 and 0.14, respectively. (F) Comparison of noise correlations measured during visual and vestibular stimulation (n=179). Arrow heads indicate mean values.

As in other cortical areas, the spike counts of MSTd neurons in response to an identical stimulus vary from trial to trial, as illustrated in Fig. 1D (visual condition) and Fig. 1E (vestibular condition). Each datum in these plots represents the spike counts of the two neurons from a single trial. Because heading direction varied across trials, spike counts from individual trials have been z-scored to remove the stimulus effect and allow pooling of data across directions (see Methods). ‘Noise correlation’ is then computed as the Pearson correlation coefficient of the normalized trial-by-trial spike counts, and reflects the degree of correlated variability across trials. For this example pair of cells, there was a weak positive correlation, such that when one neuron fired more spikes, the other neuron did as well (visual condition: rnoise = 0.29, p=0.04, Fig. 1D; vestibular condition: R=0.14, p=0.3, Fig. 1E).

We first examined whether correlated noise in MSTd depends on stimulus modality (Fig. 1F). Noise correlations computed from visual and vestibular responses were significantly correlated across 179 pairs of neurons (R=0.38, p≪0.001, Spearman rank correlation), and their means were not significantly different (vestibular: 0.035±0.014 s.e.m, visual: 0.039±0.015, p>0.8, paired t-test). Thus, to gain statistical power, we recomputed rnoise by pooling z-scored responses across stimulus conditions, thereby obtaining a single value of rnoise for each pair of neurons.

As observed in other visual areas (Huang and Lisberger, 2009; Smith and Kohn, 2008), noise correlations depended on the distance between two simultaneously recorded MSTd neurons, as illustrated in Suppl. Fig. 1, which shows distributions of rnoise for three distance groups: <0.05mm, 0.05 – 1mm and >1mm. Average noise correlations were significantly greater than zero for the first two groups (<0.05mm: 0.042±0.021 s,e,m., p=0.049, t-test; 0.05–1mm: 0.062±0.024, p=0.011), but not for the group of distant pairs (>1mm: 0±0.15, p=0.9). Thus, the following analyses were focused on 127 neuronal pairs separated by <1mm (results were similar for the whole dataset).

Comparison of noise correlations in trained and naïve animals

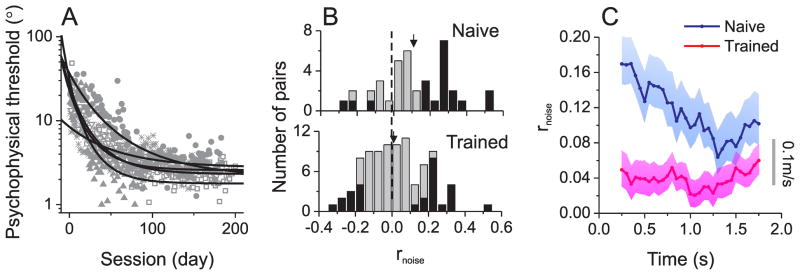

Our main goal was to examine whether training modifies interneuronal correlations. Five animals were previously trained to perform a heading discrimination task, in which they reported whether their heading was leftward or rightward relative to straight ahead (Gu et al., 2008a; Gu et al., 2007). These monkeys’ heading discrimination thresholds (corresponding to 84% correct) were high (>10°) at early stages of training, and gradually decreased to a plateau of only a few degrees (1~3°), as illustrated in Fig. 2A (Fetsch et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2008a; Gu et al., 2007). We measured noise correlations after these ‘trained’ animals had reached asymptotic performance, and we compared them to correlations measured in three ‘naïve’ animals that had never been trained to perform any task other than visual fixation.

Figure 2.

Training effects on behavior and interneuronal correlations. (A) Vestibular psychophysical thresholds from 5 monkeys (denoted by different symbol shapes) decreased gradually during training on a heading discrimination task. Solid curves: best fitting exponential functions for each animal. Thresholds are shown for the vestibular condition, not the visual condition, because optic flow stimuli were introduced later in training, and also because visual motion coherence varied across sessions to match visual and vestibular sensitivity (Gu et al., 2008a). (B) Distributions of noise correlations for ‘naïve’ (top, n=38) and ‘trained’ (bottom, n=89) animals. Black bars indicate rnoise values that are significantly different from zero. Arrows: population means. (C) Average (± sem) time course of noise correlations in ‘trained’ (red, n=89) and ‘naïve’ animals (blue, n=38).

Our most conspicuous finding was a difference in mean rnoise between ‘trained’ and ‘naïve’ animals (Fig. 2B). Correlations in trained animals were shifted toward zero, as compared to those in naïve animals. The mean noise correlation in the trained group (0.023±0.017 s.e.m, n=89) was significantly smaller than that for ‘naïve’ animals(0.116±0.031, n=38, p=0.006, t-test). Note that, for both groups of animals, rnoise was measured during an identical passive fixation task (see Methods).

Because the stimulus was dynamic (Fig. 1A, gray curve), we examined the time course of noise correlation in trained and naïve animals by computing rnoise in 500ms sliding windows (with 50ms steps). As illustrated in Fig. 2C, rnoise was significantly greater in naïve than trained animals throughout the time course of the neural response (p=0.002, permutation test, see Methods). The difference in rnoise between naïve and trained animals was largest at the beginning of the trial and gradually decreased with time (R = −0.9, p≪0.001, Spearman rank correlation, Suppl. Fig. 2A). Importantly, these observations held true when correlations were examined for individual animals (Suppl. Fig. 2B). Thus, the overall reduction in correlated noise among MSTd neurons was a robust finding in trained animals.

Effects of training on tuning curves, variability, and sensitivity of single neurons

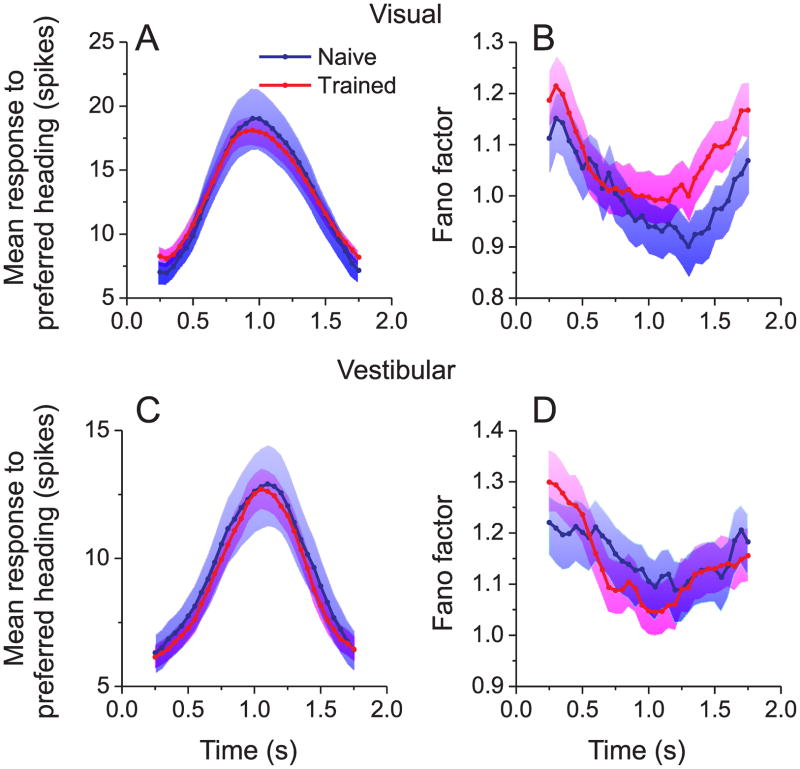

It is possible that the difference in correlated noise between naïve and trained animals could be an indirect effect of training on the response properties of individual neurons. Moreover, training-related changes in correlated noise might emerge in parallel with changes in the heading sensitivity of single neurons. To address these issues, we examined the effect of training on the time courses of firing rates and response variability. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, C, the time course of the population-average response to the preferred heading was indistinguishable between trained and naive animals (p=0.8, permutation test, see Methods). There was also no significant effect (p=0.5, permutation test) of training on the time course of the Fano factor, which measures the ratio of response variance to mean response (Fig. 3B, D, see also Methods and Suppl. Fig. 3). This finding contrasts with a previous report that Fano factor in area V4 was significantly reduced after animals were trained to discriminate orientation (Raiguel et al., 2006). In MSTd, the difference in noise correlation between naïve and trained animals does not appear to be linked to changes in firing rates or Fano factors.

Figure 3.

Training does not affect the time courses of mean responses and response variability during visual (top) and vestibular (bottom) stimulation. (A, C) Time course of the average response to stimuli presented at each cell’s preferred heading in ‘trained’(red, n=146) and ‘naïve’ animals (blue, n=64). Error bands: s.e.m. (B, D) Time course of Fano factor in ‘trained’ (red) and ‘naïve’ (blue) animals. Error bands: 95% confidence intervals. Data were derived from the same 127 pairs of neurons as in Fig. 2B, C.

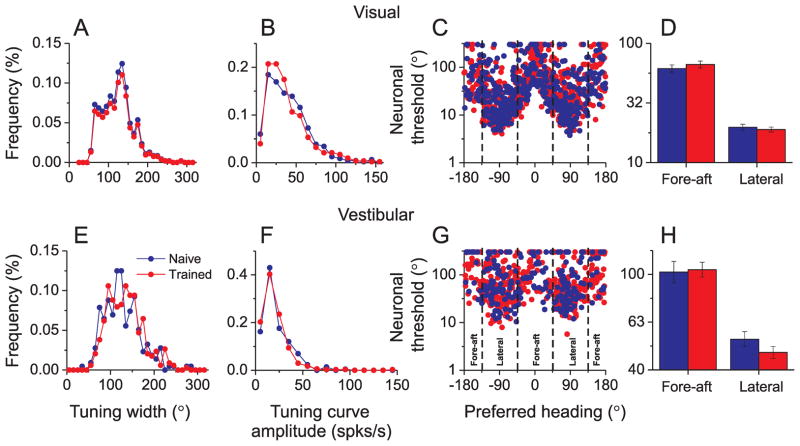

We further explored whether training shaped the tuning properties of individual MSTd neurons. For this analysis, we only included neurons with significant heading tuning in the horizontal plane (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). To gain statistical power, we exploited a much larger database of single-unit responses from naïve and trained animals, recorded with a single electrode (Vestibular: n=556; Visual: n=992). As shown in Fig. 4A, E, distributions of tuning width (full width at half-height) were very similar for naïve and trained animals. There was no significant difference in median tuning width for the visual condition (naïve: 124.5° vs. trained: 126°, p=0.21, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). The difference in median tuning width was significant for the vestibular condition (naïve: 121° vs. trained: 131°, p=0.045). However, this effect was weak and, notably, training slightly increased tuning width in the vestibular condition, an effect opposite to that expected if training increases discriminability (e.g. Yang and Maunsell, 2004). Similarly, as shown in Fig. 4B, F, training did not have any significant effect on the distribution of tuning curve amplitudes in either the visual condition (naïve: 35.4° vs. trained: 31.8°, p=0.24, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) or the vestibular condition (naïve: 17.4° vs. trained: 17.2°, p=0.36). Thus, training animals to perform a fine heading discrimination task did not significantly shape the heading tuning of individual MSTd neurons.

Figure 4.

Effects of training on heading tuning in MSTd during visual (top) and vestibular (bottom) stimulation. (A, E) Distributions of tuning width (full width at half-maximum response) for naïve (blue) and trained (red) animals. (B, F) Distributions of tuning curve amplitude (peak to trough modulation). (C, G) Neurons preferring lateral headings are more sensitive to heading variations around straight ahead than neurons preferring fore-aft motion, with little difference between naïve and trained animals. (D, H) Comparison of average neuronal sensitivity between fore-aft and lateral neurons (see panel G). Data were culled from a large database of MSTd neurons recorded with a single electrode. Only neurons with significant heading tuning (p<0.05, ANOVA) were included (visual: n=992; vestibular: n=556).

However, it remains possible that training only shaped the tuning of a subset of neurons that were most informative for heading discrimination around the straightforward reference used in training (e.g. Raiguel et al., 2006; Schoups et al., 2001). If so, then effects might only be seen for neurons most sensitive to heading variations around straight forward, and may have been missed in the above analysis. To examine this further, we interpolated tuning curves and used Fisher information analysis (Gu et al., 2010, see Methods) to compute the sensitivity of each neuron for discriminating heading around straight forward. As shown in Fig. 4C, G, the most sensitive neurons (lowest thresholds) are generally those that prefer lateral headings, such that their tuning curves have a steep slope around straight-ahead. For quantitative analysis, neurons were divided into two groups by heading preference: ’fore-aft’ neurons with heading preferences within 45° of forward (0°) or backward (±180°) motion, and ‘lateral’ neurons with heading preferences within 45° of leftward (−90°) or rightward (90°) movements. Consistent with previous findings (Gu et al., 2008a; Gu et al., 2010), lateral neurons were significantly more sensitive than fore-aft neurons for heading discrimination around straight ahead (p≪0.001, Factorial ANOVA, Figure 4D, H). However, neuronal sensitivity was not significantly different between naïve and trained animals (p>0.5, Factorial ANOVA) for either group of neurons, with no significant interaction effect (p>0.3). In summary, whereas heading discrimination training clearly reduced correlated noise among MSTd neurons, we find no clear evidence that training altered the basic tuning properties or sensitivity of individual neurons, including those neurons that are most informative for performing the task. This result also generalizes to neuronal discrimination of heading about any arbitrary reference (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Training effects on the noise-signal correlation structure

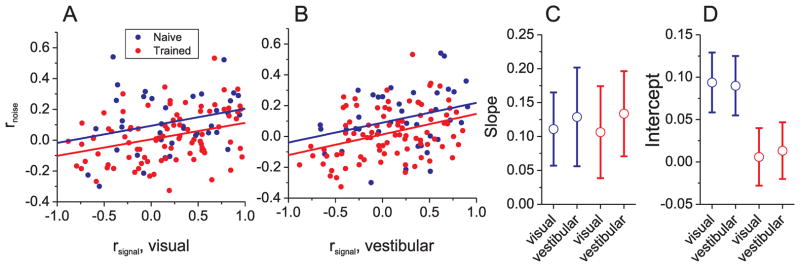

It is well established that rnoise is related to rsignal (Cohen and Maunsell, 2009; Cohen and Newsome, 2008; Gutnisky and Dragoi, 2008; Huang and Lisberger, 2009; Kohn and Smith, 2005; Smith and Kohn, 2008; Zohary et al., 1994b), so it is important to evaluate whether training alters this relationship. Fig. 5A,B shows the relationship between rnoise and rsignal, with each datum corresponding to a pair of MSTd neurons. This relationship was quantified using general linear models (analysis of covariance, ANCOVA), with rsignal in each stimulus condition (visual or vestibular) as a continuous variable and training group (trained or naïve) as a categorical factor. There was a significant positive correlation between rnoise and rsignal in both stimulus conditions (vestibular: p=0.0001; visual: p=0.0004, ANCOVA), reflecting the fact that noise correlations tended to be positive for pairs of neurons with similar tuning (rsignal >0) and near zero or negative for pairs with opposite tuning (rsignal <0).

Figure 5.

Relationship between noise correlation (rnoise) and signal correlation (rsignal) in MSTd. (A, B) Noise correlations depend significantly on rsignal computed from visual (A) or vestibular (B) tuning curves. Lines represent regression fits (ANCOVA). Red: data from trained animals (n=89); blue: data from naïve animals (n=38). (C, D) Regression slopes (C) and intercepts (D) obtained from the fits in panels (A) and (B). Error bars: 95% confidence intervals.

Importantly, the slope of the relationship between rnoise and rsignal (Fig. 5A,B )was not significantly affected by training (vestibular: p=0.9; visual: p=0.9, ANCOVA interaction effect), as also indicated by overlap of the 95% confidence intervals around the regression slopes (Fig. 5C, nearly identical slopes were obtained by Type II regression). In contrast, training had a significant main effect on rnoise (vestibular: p=0.02; visual; p=0.008 ANCOVA), and the 95% confidence intervals around the regression intercepts were non-overlapping for naïve and trained animals (Fig. 5D). Thus, training reduced noise correlations uniformly across all signal correlations, such that the dependency of rnoise on rsignal remained unchanged.

Multisensory MSTd neurons can have matched visual and vestibular heading preferences (‘congruent’ cells) or mismatched preferences (‘opposite’ cells) (Gu et al., 2008a; Gu et al., 2006). Thus, we also tested whether rnoise depends on congruency. Specifically, the two units in each pair could be (1) both congruent, (2) both opposite or (3) a mixture of congruent and opposite cells. As illustrated in Suppl. Fig. 5, rnoise was not substantially affected by congruency. Next, we incorporate these results into an information analysis to investigate how the fidelity of population activity changes between naïve and trained animals.

Computation of covariance matrix

Although neurons were recorded pair-wise, our goal is to determine whether population activity in MSTd can account for the effect of training on behavioral sensitivity. For this purpose, we need to estimate the covariance matrix that characterizes correlations among the MSTd population in naïve and trained animals. This was done by assigning each value of the covariance matrix according to the measured noise and signal correlation structures in our data set. Because rnoise depended on rsignal in both the vestibular and visual conditions (Fig. 5A, B), both relationships were taken into account when constructing the covariance matrices. For simplicity, all neurons in the simulations discussed below were assumed to have congruent visual and vestibular heading preferences. Results were similar when variable congruency was introduced into the simulation, consistent with the observation that noise correlations were not strongly influenced by congruency (Suppl. Fig. 5).

We constructed covariance matrices with two different correlation structures (see Methods): (1) rnoise depended on rsignal with regression slopes and intercept specified according to data from naïve animals: rnoise=0.12×rsignal, vestibular+0.091×rsignal, visual+0.072, and (2) rnoise depended on rsignal with slopes and intercept derived from trained animals: rnoise=0.12×rsignal, vestibular+0.091×rsignal, visual+0.005. Note that the slopes were common across the two correlation structures, since no significant difference in slopes was found (Fig. 5C). We then used these covariance matrices to compute the precision with which a population of MSTd neurons in naïve or trained animals could discriminate heading, as described below. Importantly, noise correlations did not depend on whether trained monkeys performed a passive fixation task or the heading discrimination task (p=0.3, t-test), as shown in Suppl. Fig. 6 for a subset of neuronal pairs recorded in both tasks. Thus, we are justified in predicting heading discrimination performance from population activity measured during the fixation task for both trained and naïve animals.

Effect of training on population coding efficiency

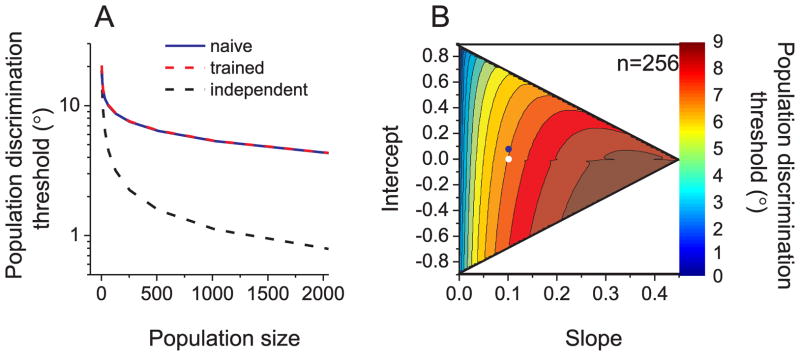

We computed population discrimination thresholds from the inverse of Fisher information (If), an upper bound on information capacity that can be extracted by any unbiased estimator (Abbott and Dayan, 1999; Seung and Sompolinsky, 1993). Predicted thresholds from If define the performance that an ideal observer could achieve, based on MSTd population activity, in a fine heading discrimination task. For a simulated population of neurons with independent noise, predicted thresholds decreased steadily with population size (Fig. 6A, dashed black curve). As expected from previous findings (Bair et al., 2001; Cohen and Maunsell, 2009; Shadlen et al., 1996; Smith and Kohn, 2008; Zohary et al., 1994b), correlated noise similar to that seen in our naïve animals degraded population coding efficiency (Fig. 6A, blue curve). For a simulated population of 2000 neurons, the predicted heading discrimination threshold was ~5-fold larger compared to the case of independent noise. Surprisingly, the uniform reduction in rnoise that we observed in trained animals (Fig. 5) had little effect on predicted discrimination thresholds, as compared to naïve animals (Fig. 6A, red curve).

Figure 6.

Impact of noise correlations on population coding efficiency. (A) Population heading discrimination thresholds as a function of population size. Each simulated population contained neurons with wrapped-Gaussian tuning curves (bandwidth=135°) and uniformly distributed heading preferences. Blue, dashed-red and dashed-black curves denote 3 correlation structures that correspond to ‘naïve’, ‘trained’, and independent (rnoise =0) neuronal cell pairs, respectively. (B) Contour plot illustrating population (n=256) discrimination thresholds (color coded) as a function of the slope and intercept of the relationship between rnoise and rsignal. The white region corresponds to a parameter range in which rnoise could exceed the allowable range of [−1 1]. Blue and white symbols denote the parameters measured in ‘naïve’ and ‘trained’ animals, respectively.

Why doesn’t the reduction in mean noise correlation seen in trained animals improve the sensitivity of the population code? We simulated performance of a population of neurons using many covariance matrices that were constructed by systematically varying both the slope and intercept of the relationship between rnoise and rsignal. As shown in Fig. 6B, predicted thresholds were very sensitive to changes in the slope of the relationship between rnoise and rsignal. In contrast, changes in the intercept of the rnoise vs. rsignal relationship had weak effects on predicted thresholds. Counterintuitively, a uniform increase in rnoise (across all values of rsignal) produced a mild decrease in population thresholds, improving performance slightly (barely visible in Fig. 6A, see also Abbott and Dayan, 1999; Wilke and Eurich, 2002). These simulations suggest that a uniform reduction of noise correlations in trained animals is expected to have little impact on discrimination performance.

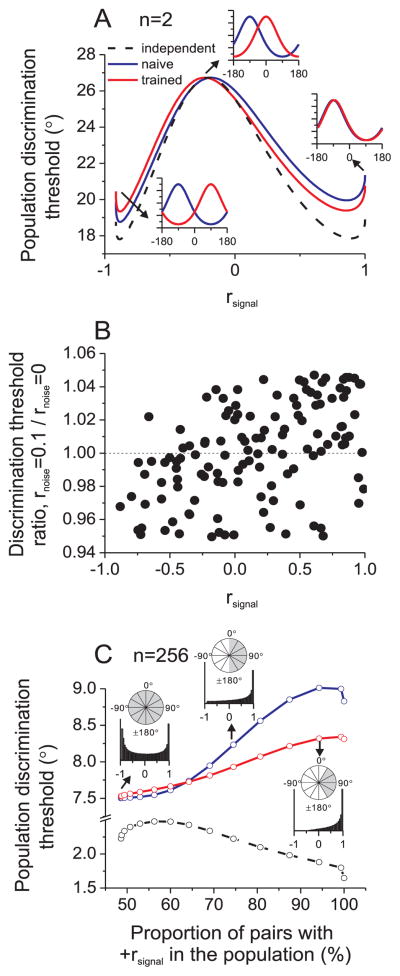

This conclusion is based on the assumption that all neurons contribute to discrimination performance. We can infer from the simulations of Fig. 6B that a change in noise correlation produces different effects for neurons with positive and negative signal correlations. To illustrate this, consider a population consisting of a single pair of neurons, having rsignal that could range from −1 (opposite heading preferences) to +1 (matched preferences). As illustrated in Fig. 7A, reducing the noise correlation between this pair of neurons results in a lower population threshold (red curve below blue curve) when the pair of neurons has positive rsignal. In contrast, reducing noise correlation increases the predicted threshold for negative rsignal (see also Supplementary Fig. 7A). This simple prediction was confirmed when decoding responses of pairs of MSTd neurons. For each pair of neurons, we compute a discrimination threshold under the assumption of correlated noise, as well as the assumption of independent noise. As shown in Fig. 7B, pairs of neurons with positive rsignal yield discrimination thresholds that increase with rnoise, whereas pairs with negative rsignal have discrimination thresholds that decrease with rnoise (R=0.49, p≪0.001, Spearman rank correlation). Thus, in a population of neurons with an even mixture of positive and negative signal correlations, the opposite effects of correlated noise will counteract each other.

Figure 7.

Reduced noise correlations improve coding efficiency for neurons with similar tuning and reduce coding efficiency for neurons with dissimilar tuning. (A) Heading discrimination thresholds a pair of neurons with various signal correlations. One neuron has a fixed heading preference of −90°, while the other cell’s heading preference varies from −90° (right inset) to 0° (middle inset) to 90° (left inset). (B) For each pair of MSTd neurons (each datum), we computed the ratio of discrimination thresholds for rnoise=0.1 and rnoise=0. A ratio of 1 (dashed line) indicates that correlated noise did not affect sensitivity. (C) Predicted discrimination thresholds for a population of 256 neurons with a variable distribution of heading preferences. From left to right, the range of heading preferences narrowed from a uniform distribution ([−180° 180°]) to only rightward headings near 90°. This generated varying distributions of signal correlations, as illustrated for 3 cases with proportions of positive rsignal values equal to 49% (heading preference range: [−180° 180°]), 75% ([0° 180°]), and 94% ([30° 150°]), as denoted by gray shading in insets. Blue, red, and black curves represent correlation structures corresponding to ‘naïve’, ‘trained’, and independent, respectively.

With this intuition in hand, we consider larger pool sizes (e.g., n=256 in Fig. 7C). If the direction preferences of neurons in the population are broadly distributed, roughly equal numbers of cell pairs will have positive and negative rsignal (Fig. 7C, left inset) and population thresholds for naïve and trained animals will be similar. If we narrow the distribution of direction preferences to generate more cell pairs with positive rsignal, the weaker noise correlations in trained animals substantially enhance coding efficiency (Fig. 7C, middle and right insets, see also Supplementary Fig. 7B). The more similar the heading tuning among neurons in the population, the greater the benefit of reducing noise correlations. At best, however, the predicted population discrimination threshold for trained animals is ~8% lower than for naïve animals (Fig. 7C, right inset, see also Supplementary Fig. 7B). Clearly, the effect of interneuronal correlations on population coding depends critically on the structure of the correlations, which involves both the relationship between rnoise and rsignal and the distribution of tuning similarity among neurons.

Possible rsignal distributions in area MSTd

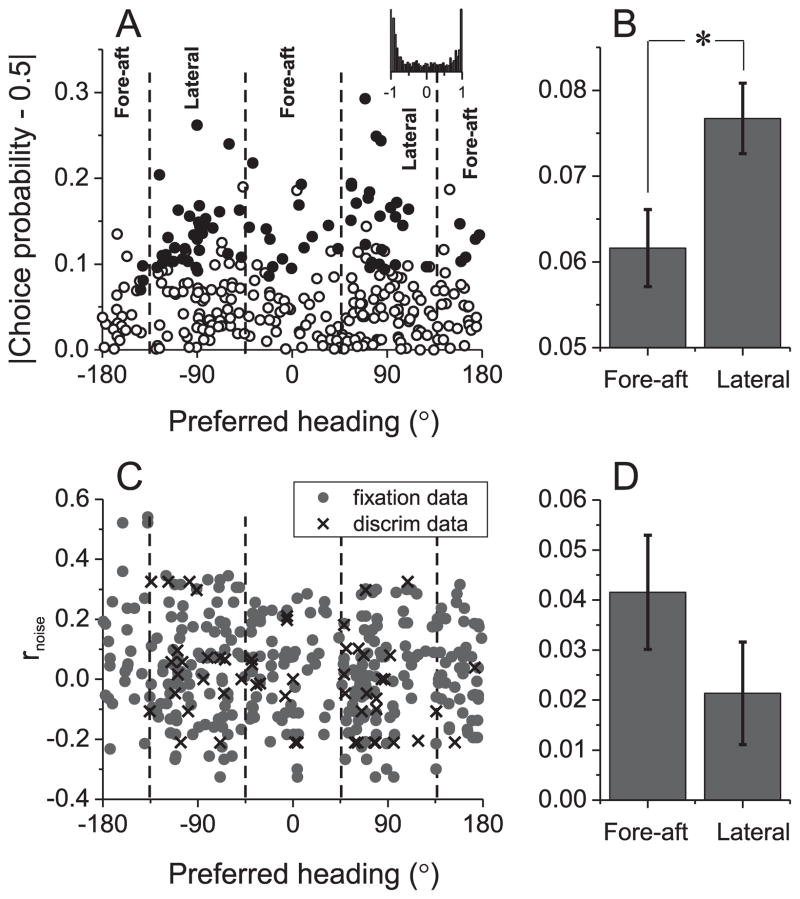

Might heading be decoded from a subpopulation of MSTd neurons with similar tuning properties (positive rsignal), such that the uniform reduction of rnoise in trained animals might improve discrimination performance? Although we cannot firmly exclude this possibility, two observations suggest that it is unlikely. First, electrical microstimulation of multi-unit clusters with either leftward or rightward heading preferences can bias choices during a heading discrimination task (Britten and van Wezel, 1998, 2002; Gu et al., 2008b). Second, significant choice probabilities, which may reflect the contribution of single cortical neurons to behavior (Britten et al., 1996; Gu et al., 2007; Purushothaman and Bradley, 2005) (but also see Nienborg and Cumming, 2010), were reported for MSTd neurons preferring both rightward and leftward headings (Gu et al., 2008a; Gu et al., 2007). Thus, we further examined the dependence of choice probability and noise correlation on heading preference.

Compared to neurons with lateral heading preferences, neurons with a preference for fore-aft movement show significantly smaller choice probabilities (p=0.019, t-test, Fig. 8A, B). This result is consistent with the notion that neurons with direction preferences deviated away from straight ahead are more sensitive to small heading variations and thus contribute more to perception (Gu et al., 2007; Purushothaman and Bradley, 2005). Importantly, there was no significant difference in average choice probability between neurons preferring leftward and rightward headings (p=0.11, t-test), suggesting that the population of neurons that contributes to heading perception includes cells with both positive and negative signal correlations (inset to Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

Relationships between choice probability, noise correlation, and heading preferences in MSTd. (A) Choice probability tends to be more deviated away from the chance level of 0.5 for neurons with lateral heading preferences. Filled symbols denote choice probabilities significantly different from 0.5 (p<0.05, permutation test). Dashed lines denote category boundaries for lateral and fore-aft cells. Inset: distribution of expected signal correlations when heading preferences are drawn randomly from cells with significant choice probabilities. (B) Mean±S.E.M of the choice probability data from (A), sorted into groups for lateral and fore-aft neurons (*, p < 0.05). Data were collected from previous experiments conducted with a single electrode (n=311), and pooled across vestibular and visual conditions. (C) Noise correlations did not depend significantly on heading preference. Pairs of cells denoted by gray circles and crosses were recorded during fixation (n=328) and discrimination tasks (n=55), respectively. For each pair, the noise correlation is plotted twice, at the preferred heading of each neuron. (D) Mean±S.E.M of the noise correlation data from (C).

Interestingly, a similar dependence on heading preference was not observed for noise correlations in trained animals. As shown in Fig. 8C, D, there was no significant dependence of noise correlation on the heading preferences of MSTd neurons (p=0.2, t-test). Indeed, the average noise correlation for lateral neurons is a bit smaller than that for the fore-aft neurons. This finding suggests that the variation in choice probability with heading preference (Fig. 8A, B) is not driven just by correlated noise, but also depends on other factors such as how the signals are read out by decision circuitry.

DISCUSSION

By recording simultaneously from pairs of neurons in macaque area MSTd, we have shown that interneuronal correlations are weaker, on average, in animals trained to perform a fine heading discrimination task as compared to animals experienced only in visual fixation tasks. Although we did not record from the same animals before and after training, the difference in correlated noise between naïve and trained subjects was highly significant and consistent across animals within each group.

Our findings suggest that changes in the average strength of noise correlations are not sufficient to account for the effect of training on discrimination performance. The difference in rnoise between naïve and trained animals was uniform and independent of tuning similarity. If all neurons are decoded uniformly, the increased information capacity of neuronal pools with similar tuning is counteracted by the decreased information capacity of neuronal pools with dissimilar tuning curves. Thus, the effect of correlated noise on discrimination performance is conditional on both the relationship between rnoise and rsignal and on the demands of the task which may recruit different neuronal pools into play.

Properties of noise correlations in MSTd

Compared to noise correlations observed in area MT (Bair et al., 2001; Cohen and Newsome, 2008; Huang and Lisberger, 2009; Zohary et al., 1994b), the average noise correlation in our MSTd sample (distance <1mm) was substantially weaker (trained animals: 0.023; naïve animals: 0.116). The average correlation values we have seen in trained animals are similar to those reported in a recent study of macaque primary visual cortex (Ecker et al., 2010).

We found that noise correlations in MSTd are independent of the sensory stimulus modality (visual or vestibular), but depend on distance such that nearby neurons tend to have stronger correlations than more distant pairs (Huang and Lisberger, 2009; Lee et al., 1998; Smith and Kohn, 2008). Correlations in MSTd also depend strongly on tuning similarity, such that neurons with similar tuning curves tend to have greater correlated noise. In addition, we observed that noise correlations decrease in the presence of a stimulus as compared to pre-stimulus baseline activity. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that noise correlations decreased following stimulus onset (Smith and Kohn, 2008) and increased with stimulus intensity (e.g., contrast) (Huang and Lisberger, 2009; Kohn and Smith, 2005).

Possible explanations for the effect of training on correlated noise

Before accepting the conclusion that correlated noise in MSTd was reduced as a consequence of perceptual learning, we consider some alternatives. One possibility is that naive monkeys undergo larger fluctuations in behavioral state (e.g., arousal, attention) than trained animals, and this might cause slow fluctuations in neuronal responses that can inflate noise correlations (Bair et al., 2001; Ecker et al., 2010; Lampl et al., 1999). To address this issue, we removed slow fluctuations in neural responses by renormalizing the data before computing noise correlations (see Methods, Zohary et al., 1994b). This operation had little effect on our measurements, for both naïve and trained animals (Supplementary Fig. 8). This suggests that slow fluctuations in response driven by variations in behavioral state do not account for the greater noise correlations seen in naive animals.

Another possibility is that naive animals fixate the visual target less reliably and make more frequent microsaccades that could induce correlations among neural responses (e.g., Bair and O’Keefe, 1998). However, we found that naïve animals fixate as accurately as trained animals (Supplementary Fig. 8A). Indeed, naïve monkeys as a group made significantly fewer microsaccades than trained animals (Supplementary Fig. 8B). Hence, the reduction of correlated noise in trained animals is unlikely to be explained by differences in eye movements between the two groups of animals.

Two recent studies have indicated that attention directed toward the receptive field could reduce correlated noise among pairs of neurons in area V4 (Cohen and Maunsell, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009). Although both naïve and trained monkeys only performed a passive fixation task in our study, trained animals might have paid more attention to the heading stimuli due to their relevance in the discrimination task. We cannot exclude this possibility, but three aspects of our results are inconsistent with an explanation based on attention. First, attention typically increases neuronal activity (Desimone and Duncan, 1995; Kastner and Ungerleider, 2000; Reynolds and Chelazzi, 2004; Reynolds and Heeger, 2009; Treue and Maunsell, 1999), but our analysis shows that mean responses were not significantly different between naïve and trained animals (Fig. 3). Second, the reduction in noise correlation with increased attention was also accompanied by decreased neuronal variability (Fano factor, Cohen and Maunsell, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009). However, we did not find a significant difference in Fano factor between naïve and trained animals. Finally, there was no difference in noise correlation between the fixation and discrimination tasks for a subset of pairs of neurons that were recorded during both tasks (Suppl. Fig. 6). This result is consistent with an earlier study in which noise correlations in area MT were found to be similar during a motion discrimination task and a visual fixation task (Zohary et al., 1994b).

Any fluctuation in common inputs could cause correlated variability among target neurons. It is thus possible that training decreases the shared, common input to area MSTd, likely on a long time scale during learning (Chowdhury and DeAngelis, 2008). The effect of training on neural circuitry may have occurred at two levels. First, training may have altered the feedforward sensory input to MSTd from other cortical and subcortical areas, without changing the average tuning properties of single neurons (Jenkins et al., 1990; Recanzone et al., 1993; Weinberger, 1993). Second, training may have altered feedback connections to MSTd, including feedback from decision circuitry. Our results are consistent with recent findings that perceptual learning does not substantially alter sensory cortical representations, but rather sculpts the decoding of sensory signals by decision circuitry (Dosher and Lu, 1999; Law and Gold, 2008). If training alters the read out of heading signals from MSTd, this in turn may modify the shared feedback to MSTd neurons from downstream circuitry. It is currently not possible to discern which of these training-related changes contributes most to the reduction in correlated noise that we have observed.

Although our data suggest that learning does not alter the sensory representation of heading in a manner that could account for the improvement in behavioral sensitivity with training, it is important to note that we cannot rule out the possibility that training altered the heading tuning and sensitivity of neurons in other brain areas that may also be involved in heading perception, such as area VIP (Zhang and Britten, 2011). In addition, although we assume that noise correlations in MSTd were altered by perceptual learning, we cannot exclude the possibility that some other aspect of training, such as learning the operational rules of the task, may have driven the changes in correlated noise that we have observed. Finally, it is unclear whether the effect of training on correlated noise is specific to tasks for which area MSTd is thought to provide critical input. If we had trained animals to perform a task that was irrelevant to self-motion perception, such as a somatosensory or auditory discrimination task, we presumably would not expect to see changes in correlated noise in MSTd. However, this possibility remains to be tested.

Consequences for population coding efficiency

Despite a robust effect of training on the average noise correlation in MSTd, our simulations show that an optimal, unbiased decoding of all neurons does not predict a substantial change in performance due to learning. Indeed, theorists have shown that correlated noise may or may not harm population coding (Abbott and Dayan, 1999; Averbeck et al., 2006; Wilke and Eurich, 2002). In general, positively correlated noise between neurons with similar tuning (or more generally, any situation in which both neurons fire more strongly under one stimulus/task condition than another) harms the signal to noise ratio of the population code because it cannot be removed by pooling across neurons (Bair et al., 2001; Shadlen et al., 1996; Zohary et al., 1994b). Reducing shared noise among neurons in such cases is thus expected to improve population sensitivity.

Indeed, the effect of attention on the fidelity of population codes appears to follow this logic (Cohen and Maunsell, 2009). In a typical spatial attention task, most neurons with receptive fields at the attended location will increase their response. Because attention has a consistent polarity of effect on the responses of nearby neurons, stronger attention will tend to increase the responses of both neurons in a pair. Hence, most pairs of nearby neurons will have positive signal correlations with respect to the effect of attention. As a result, a reduction in correlated noise due to attention can improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the population code. However, in other contexts for which signals are decoded from populations that include neurons with dissimilar tuning properties, increasing correlated noise can improve the signal-to-noise ratio of a population code (Fig. 7A), as differences in tuning effectively cancel more of the noise in a population response (Abbott and Dayan, 1999; Averbeck et al., 2006; Poort and Roelfsema, 2009; Wilke and Eurich, 2002). Reducing correlated noise in the latter case can harm the coding efficiency of the population. In our heading discrimination task, it is likely that responses are decoded from neurons with a broad range of heading preferences (Gu et al., 2008b; Gu et al., 2010); in this context, reducing correlated noise uniformly across neurons with all signal correlations (Fig. 5A& B) does not improve the fidelity of the neural code (Fig. 6A). Thus, the impact of correlated noise on population coding depends on: (1) the structure of noise correlations and their dependence on signal correlation, and (2) the composition of neuronal pools upon which decoding is based.

We conclude that the effects of training on heading discrimination are not likely to be driven by the reduction in correlated noise that we have observed in area MSTd. Combined with previous observations that perceptual learning has little or no effect on basic tuning properties of single neurons in visual cortex (Chowdhury and DeAngelis, 2008; Crist et al., 2001; Ghose et al., 2002; Law and Gold, 2008; Raiguel et al., 2006; Schoups et al., 2001; Yang and Maunsell, 2004; Zohary et al., 1994a), our results suggest that changes in sensory representations are not necessarily involved in accounting for the improvements in behavioral sensitivity that accompany perceptual learning (at least for some sensory systems and tasks). Rather, our findings support the idea that perceptual learning may primarily alter the routing and/or weighting of sensory inputs to decision circuitry, an idea that has recently received experimental support (Chowdhury and DeAngelis, 2008; Law and Gold, 2008, 2009).

METHODS

Subjects

Physiological experiments were performed in 8 male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 4–8 kg. Animals were chronically implanted with a plastic head-restraint ring that was firmly anchored to the apparatus to minimize head movement. All monkeys were implanted with scleral coils for measuring eye movements in a magnetic field (Robinson, 1963). Animals were trained using standard operant conditioning to fixate visual targets for fluid reward. All animal surgeries and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington University and were in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Motion stimuli

Neurons were tested with two types of motion stimuli using a custom-built virtual reality system (Gu et al., 2007, 2008b; Gu et al., 2006). In the ‘vestibular’ stimulus condition, monkeys were passively translated by a motion platform (MOOG 6DOF2000E; East Aurora, NY) along a smooth trajectory (Gaussian velocity profile with peak-acceleration of ~1 m/s2 and duration of 2s, Fig. 1A). In the ‘visual’ stimulus condition, optic flow was provided by rear-projecting images onto a tangent screen in front of the monkey using a 3-chip DLP projector (Christie Digital Mirage 2000) that was mounted on the motion platform. Visual stimuli (90×90°) depicted movement through a 3D cloud of stars that occupied a virtual space 100 cm wide, 100 cm tall, and 50 cm deep. The stimulus contained multiple depth cues, including horizontal disparity, motion parallax and size information.

Experimental protocol and task

Animals were trained to maintain visual fixation on a head-fixed target at the center of the screen. Eye position was required to stay within a 2×2° electronic window throughout each trial in order to receive a water/juice reward. The majority of the data presented here were recorded while passively-fixating animals experienced a range of different heading directions that spanned the horizontal and/or vertical plane (Gu et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2007). Specifically, headings relative to straight ahead were: 0, ±22.5, ±45, ±90, and ±135º. Different heading directions and stimulus types (visual or vestibular) were interleaved randomly within a single block of trials. Each distinct stimulus was typically repeated 5 times (minimum of 3 repetitions for inclusion).

In each trial, a fixation point first appeared at the center of the screen. After fixation was established for 100–200 ms, the motion stimulus began and lasted for 2 seconds. In the vestibular condition, the motion platform always began its movement from a common central position. The animal was rewarded if they maintained visual fixation throughout the duration of the stimulus. At the end of the trial (or when fixation was broken), the fixation point disappeared and the motion platform moved back to the original central position during a 2 second intertrial interval. In the visual condition, the random-dot field appeared on the display after fixation was established, and again moved for 2 seconds. The dots then disappeared and the animal was rewarded for maintaining fixation, followed again by a 2 sec intertribal interval.

Three animals were trained only to perform the passive fixation task, whereas 5 animals had been extensively trained to perform a heading discrimination task (Fetsch et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2008a; Gu et al., 2007), in which they were asked to report whether their perceived heading was leftward or rightward relative to straight ahead by making a saccade to one of two choice targets. For a subpopulation of neurons in these ‘trained’ animals, responses were obtained while the animals performed both the fixation task and the heading discrimination task

Electrophysiological recordings

We conducted extracellular recordings of action potentials from single neurons in area MSTd. For most recordings, 2 to 4 tungsten electrodes (Frederick Haer, Bowdoinham, ME; tip diameter 3 μm, impedance 1–2 MΩ at 1 kHz) were used to record multiple single neurons simultaneously. In some cases (57 pairs), 2–4 electrodes were placed inside multiple guide tubes separated by 0.8 to 25 mm (different hemispheres). In other cases (55 pairs), multiple electrodes were placed inside a single guide tube. The distance between two simultaneously recorded neurons was estimated from both the horizontal and vertical (depth) coordinates (shank diameter = 75 microns).

Data from another 67 cell pairs were obtained from previous recordings with a single electrode (Fetsch et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2007), for which a second cell was isolated off-line using spike sorting software (Spike2, Cambridge Electronics Design). Only pairs of neurons from a single electrode that showed clearly separate clusters in the first three principle components of the spike waveform were included in the sample. Since the exact distance between neurons recorded from a single electrode was unknown, we arbitrarily assigned it to be 50 microns. Although noise correlations were slightly greater for pairs of neurons recorded from a single electrode (0.042±0.02) than for pairs recorded from different electrodes (0.033±0.015), this difference was modest and not significant (p>0.7, t-test). Thus, data collected with single and multiple electrodes were pooled for analysis, yielding 179 cell pairs from a total of 270 neurons (maximum of 5 pairs in an experiment).

Area MSTd was located ~15 mm lateral to the midline and ~2–6 mm posterior to the interaural plane, and was identified using both MRI scans and neurophysiological response properties (see Gu et al., 2006 for details). MSTd neurons had large receptive fields that typically occupied a quadrant or a hemi-field on the display screen and were often centered in the contralateral visual field but could extend well into the ipsilateral field. Once the electrodes were targeted to MSTd, we recorded from any neuron that was spontaneously active or could be activated by patches of flickering dots.

Data analysis

Noise and signal correlations

Noise correlation (rnoise) was computed as the Pearson correlation coefficient (ranging between −1 and 1) of the trial-by-trial responses from a pair of neurons driven by the same stimulus (Bair et al., 2001; Zohary et al., 1994b). The response in each trial was taken as the number of spikes during the middle 1s of the stimulus period (Gu et al., 2006). For each heading direction, responses were z-scored by subtracting the mean response and dividing by the standard deviation. This operation removed the effect of heading on the responses, such that the measured noise correlation reflected trial-to-trial variability. To avoid artificial correlations caused by outliers, we removed data points with z-scores larger than 3 (Zohary et al., 1994b). We then pooled data across headings to compute rnoise; the corresponding p-value was used to assess the significance of correlation for each pair of neurons.

Because there was no significant difference in rnoise between visual and vestibular stimulus conditions (Fig. 1F), we pooled responses across conditions to gain statistical power. To remove slow fluctuations in responsiveness that could result from changes in cognitive state over time (e.g., arousal), we re-normalized the z-scored responses in blocks of 20 trials, as described by Zohary et al (1994b). This additional normalization had no significant effect on rnoise (p>0.3, paired t test; R=0.9, p≪0.001, Spearman rank correlation, n=127, Supplementary Fig. 8). More importantly, the effect of re-normalization on noise correlations was similar in naïve and trained animals (p=0.7, interaction effect, p=0.9, group effect, ANCOVA, Supplementary Fig. 8). This suggests that the greater noise correlations in naïve animals were not the result of larger slow fluctuations in neural response (Ecker et al., 2010), such as might arise if naïve animals experienced greater fluctuations in arousal during the session.

Signal correlation (rsignal) was computed as the Pearson correlation coefficient (ranging between −1 and 1) between the tuning curves from two simultaneously recorded neurons. Tuning curves for each stimulus condition were constructed by computing the mean response (average firing rate during the middle 1s of the stimulus duration) across trials for each heading direction.

Permutation test

Permutation tests were applied to test for significant differences between trained and naïve animals with respect to: the difference in time courses of noise correlation (Fig. 2C), mean response (Fig. 3A,C), and Fano factor (Fig. 3B, D). We first computed the sum of squared differences between two time courses:

| (1) |

using a 500ms sliding window moved in 50ms steps, for a total of 31 data points. We then created permuted ‘naïve’ and ‘trained’ groups by randomly drawing data from the original groups, pooled together. Within each cell, all of the responses were preserved (no shuffling across trials). We computed a new x2 value for each permutation (x2permuted), and this process was repeated 10000 times. A p-value was computed as the proportion of x2permuted > x2. A difference between the two groups of animals was considered significant if p < 0.05.

Fano factor

Fano factor, or the variance/mean ratio, was computed from log-log scatter plots of the variance of the spike count against the mean spike count, and this was done for each 500ms time window used to compute time courses. The data were fit by minimizing the orthogonal distance to the fitted line (type II regression). The slope was generally close to 1 and was thus forced to be 1 for convenience, such that variance scaled linearly with mean spike count. The Fano factor was then computed as 10^intercept (see Suppl. Fig. 3).

Population coding

Fisher information (IF) provides an upper limit on the precision with which an unbiased estimator can discriminate between small variations in a variable (x) around a reference value (xref) (Pouget et al., 1998; Seung and Sompolinsky, 1993). We computed the smallest deviation in heading around straight ahead (threshold, Δx) that could be reliably discriminated (at 84% correct) by an ideal observer:

| (2) |

where IF was computed according to (Abbott and Dayan, 1999):

| (3) |

Here, f’ denotes the derivative of a matrix of tuning curves; superscript T denotes the matrix transpose, Tr represents the trace operation, and superscript −1 indicates the matrix inverse. The reference heading was straight ahead in our simulations (xref=0°). Q represents the covariance matrix of neural responses, which was given by

| (4) |

where ri,j denotes the noise correlation between the ith and jth neurons. When i=j, ri,j was set to 1. When i≠j, ri,j was assigned according to a linear relationship between noise and signal correlation:

| (5) |

We minimized the orthogonal distance between the fit plane and the raw data using type II regression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NIH (EY019087 to DEA, and EY016178 to GCD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott LF, Dayan P. The effect of correlated variability on the accuracy of a population code. Neural Comput. 1999;11:91–101. doi: 10.1162/089976699300016827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelaki DE, Gu Y, DeAngelis GC. Multisensory integration: psychophysics, neurophysiology, and computation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck BB, Latham PE, Pouget A. Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:358–366. doi: 10.1038/nrn1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M, Kruger J. Correlated neuronal variability in monkey visual cortex revealed by a multi-microelectrode. Exp Brain Res. 1986;61:451–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00237570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W, O’Keefe LP. The influence of fixational eye movements on the response of neurons in area MT of the macaque. Vis Neurosci. 1998;15:779–786. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898154160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W, Zohary E, Newsome WT. Correlated firing in macaque visual area MT: time scales and relationship to behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1676–1697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01676.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH. Mechanisms of self-motion perception. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:389–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, Newsome WT, Shadlen MN, Celebrini S, Movshon JA. A relationship between behavioral choice and the visual responses of neurons in macaque MT. Vis Neurosci. 1996;13:87–100. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000715x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, van Wezel RJ. Electrical microstimulation of cortical area MST biases heading perception in monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:59–63. doi: 10.1038/259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, Van Wezel RJ. Area MST and heading perception in macaque monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:692–701. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.7.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SA, DeAngelis GC. Fine discrimination training alters the causal contribution of macaque area MT to depth perception. Neuron. 2008;60:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Maunsell JH. Attention improves performance primarily by reducing interneuronal correlations. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1594–1600. doi: 10.1038/nn.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Newsome WT. Context-dependent changes in functional circuitry in visual area MT. Neuron. 2008;60:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist RE, Li W, Gilbert CD. Learning to see: experience and attention in primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:519–525. doi: 10.1038/87470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desimone R, Duncan J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1995;18:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosher BA, Lu ZL. Mechanisms of perceptual learning. Vision Res. 1999;39:3197–3221. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker AS, Berens P, Keliris GA, Bethge M, Logothetis NK, Tolias AS. Decorrelated neuronal firing in cortical microcircuits. Science. 2010;327:584–587. doi: 10.1126/science.1179867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetsch CR, Turner AH, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Dynamic reweighting of visual and vestibular cues during self-motion perception. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15601–15612. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2574-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetsch CR, Wang S, Gu Y, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. Spatial reference frames of visual, vestibular, and multimodal heading signals in the dorsal subdivision of the medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci. 2007;27:700–712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawne TJ, Kjaer TW, Hertz JA, Richmond BJ. Adjacent visual cortical complex cells share about 20% of their stimulus-related information. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:482–489. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawne TJ, Richmond BJ. How independent are the messages carried by adjacent inferior temporal cortical neurons? J Neurosci. 1993;13:2758–2771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02758.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose GM, Yang T, Maunsell JH. Physiological correlates of perceptual learning in monkey V1 and V2. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1867–1888. doi: 10.1152/jn.00690.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone RL. Perceptual learning. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:585–612. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Angelaki DE, Deangelis GC. Neural correlates of multisensory cue integration in macaque MSTd. Nat Neurosci. 2008a;11:1201–1210. doi: 10.1038/nn.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. A functional link between area MSTd and heading perception based on vestibular signals. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1038–1047. doi: 10.1038/nn1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Effects of microstimulation in area MSTd on heading perception based on visual and vestibular cues. Society for Neuroscience abstract. 2008b:460.9. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Fetsch CR, Adeyemo B, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. Decoding of MSTd Population Activity Accounts for Variations in the Precision of Heading Perception. Neuron. 2010;66:596–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Watkins PV, Angelaki DE, DeAngelis GC. Visual and nonvisual contributions to three-dimensional heading selectivity in the medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci. 2006;26:73–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2356-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutnisky DA, Dragoi V. Adaptive coding of visual information in neural populations. Nature. 2008;452:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature06563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Lisberger SG. Noise correlations in cortical area MT and their potential impact on trial-by-trial variation in the direction and speed of smooth-pursuit eye movements. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:3012–3030. doi: 10.1152/jn.00010.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WM, Merzenich MM, Ochs MT, Allard T, Guic-Robles E. Functional reorganization of primary somatosensory cortex in adult owl monkeys after behaviorally controlled tactile stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:82–104. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Mechanisms of visual attention in the human cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:315–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A, Smith MA. Stimulus dependence of neuronal correlation in primary visual cortex of the macaque. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3661–3673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5106-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampl I, Reichova I, Ferster D. Synchronous membrane potential fluctuations in neurons of the cat visual cortex. Neuron. 1999;22:361–374. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law CT, Gold JI. Neural correlates of perceptual learning in a sensory-motor, but not a sensory, cortical area. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:505–513. doi: 10.1038/nn2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law CT, Gold JI. Reinforcement learning can account for associative and perceptual learning on a visual-decision task. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:655–663. doi: 10.1038/nn.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Port NL, Kruse W, Georgopoulos AP. Variability and correlated noise in the discharge of neurons in motor and parietal areas of the primate cortex. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1161–1170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-01161.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Piech V, Gilbert CD. Perceptual learning and top-down influences in primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nn1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JF, Sundberg KA, Reynolds JH. Spatial attention decorrelates intrinsic activity fluctuations in macaque area V4. Neuron. 2009;63:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienborg H, Cumming B. Correlations between the activity of sensory neurons and behavior: how much do they tell us about a neuron’s causality? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram MW, Foldiak P, Perrett DI, Sengpiel F. The ‘Ideal Homunculus’: decoding neural population signals. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:259–265. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poort J, Roelfsema PR. Noise correlations have little influence on the coding of selective attention in area V1. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:543–553. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget A, Zhang K, Deneve S, Latham PE. Statistically efficient estimation using population coding. Neural Comput. 1998;10:373–401. doi: 10.1162/089976698300017809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushothaman G, Bradley DC. Neural population code for fine perceptual decisions in area MT. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:99–106. doi: 10.1038/nn1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiguel S, Vogels R, Mysore SG, Orban GA. Learning to see the difference specifically alters the most informative V4 neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6589–6602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0457-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory cortex following discrimination training in adult owl monkeys. J Neurosci. 1993;13:87–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00087.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich DS, Mechler F, Victor JD. Independent and redundant information in nearby cortical neurons. Science. 2001;294:2566–2568. doi: 10.1126/science.1065839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JH, Chelazzi L. Attentional modulation of visual processing. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JH, Heeger DJ. The normalization model of attention. Neuron. 2009;61:168–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DA. A Method of Measuring Eye Movement Using a Scleral Search Coil in a Magnetic Field. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1963;10:137–145. doi: 10.1109/tbmel.1963.4322822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoups A, Vogels R, Qian N, Orban G. Practising orientation identification improves orientation coding in V1 neurons. Nature. 2001;412:549–553. doi: 10.1038/35087601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung HS, Sompolinsky H. Simple models for reading neuronal population codes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10749–10753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MN, Britten KH, Newsome WT, Movshon JA. A computational analysis of the relationship between neuronal and behavioral responses to visual motion. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1486–1510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01486.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Kohn A. Spatial and temporal scales of neuronal correlation in primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12591–12603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2929-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sompolinsky H, Yoon H, Kang K, Shamir M. Population coding in neuronal systems with correlated noise. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2001;64:051904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.051904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Gu Y, May PJ, Newlands SD, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Multimodal coding of three-dimensional rotation and translation in area MSTd: comparison of visual and vestibular selectivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9742–9756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0817-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treue S, Maunsell JH. Effects of attention on the processing of motion in macaque middle temporal and medial superior temporal visual cortical areas. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7591–7602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07591.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM. Learning-induced changes of auditory receptive fields. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1993;3:570–577. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke SD, Eurich CW. Representational accuracy of stochastic neural populations. Neural Comput. 2002;14:155–189. doi: 10.1162/089976602753284482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Maunsell JH. The effect of perceptual learning on neuronal responses in monkey visual area V4. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1617–1626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4442-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Britten KH. Parietal area VIP causally influences heading perception during pursuit eye movements. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2569–2575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5520-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohary E, Celebrini S, Britten KH, Newsome WT. Neuronal plasticity that underlies improvement in perceptual performance. Science. 1994a;263:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.8122114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohary E, Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Correlated neuronal discharge rate and its implications for psychophysical performance. Nature. 1994b;370:140–143. doi: 10.1038/370140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.