Abstract

Research into how self-reactive T cells are tolerized in lymph nodes has focused largely on dendritic cells (DCs). We now know that lymph node stromal cells (LNSC) are important mediators of deletional tolerance to peripheral tissue-restricted antigens (PTAs). PTAs are constitutively expressed and presented by LNSCs. Of the major LNSC subsets, fibroblastic reticular cells and lymphatic endothelial cells are known to directly induce tolerance of responding naïve CD8 T cells. The biological outcome of this interaction fills a void otherwise not covered by DCs or thymic stromal cells. These findings, we suggest, necessitate a broadening of peripheral tolerance theory to include steady-state presentation of clinically relevant PTA to naïve CD8 T cells by lymph node-resident stroma.

A paradigm shift in tolerance mechanisms

To be effective, the adaptive immune system requires antigen presenting (APCs) cells to strike a balance between presentation of innocuous self-antigen in a manner that fails to activate self-reactive T cells, and presenting perceived “dangerous” antigen in manner that induces T cell activation and immune competence. T cells themselves have randomly derived specificity, and a normal T cell repertoire contains a high frequency of autoreactive cells that have escaped thymic negative selection[1]. The outcome of T cell stimulation in secondary lymphoid organs is therefore controlled by signals from the APC; for example, a T cell activated by a DC without required accompanying signals becomes functionally inert or is deleted.

In the lymph node, both resident and incoming DCs adopt the tolerance versus activation decision-making role[2–4]. Thus, APCs do not have to directly sample antigen from its peripheral source; instead, antigen and activating stimuli can be carried to the lymph node via lymph and other trafficking cells, to activate resident APCs which then influence T cell fate in situ. Profiling of medullary thymic epithelial cell (mTEC)-mediated peripheral tissue-restricted antigen (PTA) expression has also demonstrated that organ-resident non-hematopoietic stroma are capable of potent tolerance induction [5–7]. A role for stroma in influencing the outcome of T cell activation therefore makes intuitive and evolutionary sense. Until recently, however, the prevailing peripheral tolerance model relied heavily on DCs as its cellular centerpiece [8–10]. Under this model, deletional tolerance to PTAs required one of: 1) PTA expression by the thymic epithelium during thymocyte development [5, 6]; 2) DC trafficking to draining lymph nodes from peripheral tissues [9–11]; or 3) cell independent transfer of antigen from organ to lymph node [4].

Like other stromal populations, lymph node stromal cells (LNSC) were once thought to function solely as parenchymal support. However, it is now known that lymph node stromal cells (LNSC) exert potent and biologically relevant influence over immune cell function. New evidence shows that all LNSC cell types express PTA, and that LNSC can directly activate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells under both steady-state and inflammatory conditions. Here, we review this data and describe a new paradigm of peripheral tolerance, while highlighting areas of knowledge that are still mechanistically and functionally evolving [12–17].

LNSCs and lymph node architecture

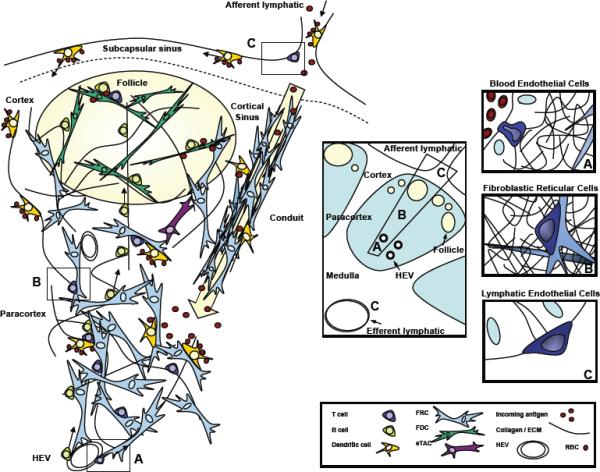

The complex lymph node stromal structure is perhaps best described as a dense mesenchymal vascularized network interrupting and enclosed by a lymphatic vessel. Beginning at embryonic day 12.5, the lymph node anlagen is created by an area of mesenchyme that buds into and compresses a lymphatic vessel, which in turn bends, grows, and eventually encapsulates the mesenchymal bud (reviewed by [18]). The lumen of the lymphatic vessel develops into a system of sinuses that permeate the fibroblastic core of the lymph node. Lymph therefore arrives through afferent lymphatic vessels that are continuous with the subcapsular sinus at the cortical face of the lymph node. The vessels empty their contents and creating directional flow through what is effectively a fibroblastic filter (Figure 1). Efferent lymphatics drain the lymph node at the medullary face [18, 19].

Figure 1. T cells interact with multiple lymph node stromal cell types known to express peripheral tissue-restricted antigens.

A. Most T cells enter the lymph node from the bloodstream through HEV lined by specialized blood endothelial cells in the paracortex.

B. While in the lymph node, T cells crawl throughout the paracortex on the extensive FRC network, interacting with antigen-bearing dendritic cells.

C. T cells interact with lymphatic endothelial cells. This occurs occasionally as the route of entry to the lymph node through afferent lymphatics for some activated T cells, and very commonly as an exit route through efferent lymphatics for naïve T cells.

T cell interaction with other stromal subsets, including FDC and eTAC is likely to occur but is not well defined. FRC: fibroblastic reticular cell. FDC: follicular dendritic cell. eTAC: extra-thymic Aire-expressing cell. ECM: extracellular matrix. HEV: high endothelial venule.

Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRC), which secrete collagen and other extracellular matrix components, are defined by surface expression of glycoprotein gp38 (podoplanin) and form the mesenchymal backbone on which T cells, B cells and dendritic cells (DC) migrate and interact [20, 21]. FRC also lay down the basement membrane to create a conduit system of fine microchannels that conduct small lymph-borne antigens and inflammatory mediators deep into the lymph node paracortex (Figure 1). This presumably activates conduit-sampling DC faster than percolating through the subcapsule and cortex, which is the route of larger proteins and cells arriving from afferent lymphatics [20, 22, 23].

While B cells use the FRC network to reach the follicles, the follicles themselves are largely free of FRCs, and are instead populated by a population of rare, non-hematopoietic mesenchymal stroma called follicular DCs (FDCs). FDCs regulate B cell homeostasis, migration and survival [24–26], as well as presenting exogenous antigen with the capacity to cross-link B cell receptors (reviewed by [27]), which is an efficient mechanism of T-independent B cell activation.

FRCs and FDCs impose separation of lymphocytes into the characteristic paracortical T cell zone interrupted by discrete B cell follicles extending into the cortex. Naïve T and B cells expressing CCR7 and CXCR4 encounter FRCs expressing CCL19, CCL21, and SDF1 (CXCL12) [28, 29]. Naïve B cells are induced to migrate into follicles through FDC expression of CXCL13, which binds CXCR5 on naïve B cells [25, 30]. These chemokines are known to regulate lymphocyte homing under lymphatic flow [31, 32]. FRCs also produce IL-7, which promotes survival of naïve T cells [28]. Together, FRCs and FDCs establish distinct T and B cell zones within lymph nodes.

Endothelial cells are also important stromal components, lining blood and lymphatic vessels that supply the lymph node with its parenchymal content. Naïve T and B cells constantly circulate through secondary lymphoid organs via blood vessels, which enter the lymph node at the medulla and terminate in high endothelial venules. Integrins expressed by high endothelial venules carefully regulate leukocyte entry to lymph nodes [33, 34]. Antigen presenting cells, antigen, and chemical mediators of inflammation arrive via afferent lymphatic vessels, which empty into the subcapsular sinus and filter through the lymph node to efferent lymphatic vessels in the medulla (reviewed by [35]).

LNSC and PTA expression

In 2007, it was reported that a gut-restricted self-antigen was ectopically expressed by LNSC in non-draining lymph nodes [12]. Strikingly, LNSC could directly present this antigen to CD8+ T cells, which were subsequently deleted, inducing tolerance [12]. In this transgenic model, truncated ovalbumin was expressed under the control of the intestinal fatty acid binding protein (iFABP) promoter [36]. When ovalbumin-specific CD8 T cells were transferred to these mice, they became activated in lymph nodes even when hematopoietic cells, including DC and all other classical APC, were prevented from presenting antigen. These T cells were induced to divide and lost from the peripheral T cell pool, resulting in tolerance [12].

Subsequent papers [13–15] confirmed and extended these results. Importantly, LNSC were shown to be responsible for inducing tolerance to endogenous antigen in a non-transgenic model of PTA expression, cementing the biological relevance of this new peripheral tolerance mechanism [13]. In this study, tolerance to tyrosinase, a melanocyte-specific self-antigen, required expression in non-hematopoietic LNSC. Although tyrosinase transcript was detected in the thymus, autoreactive T cells were not efficiently deleted when tyrosinase-sufficient thymi were transplanted to albino mice lacking tyrosinase [13]. However, tyrosinase-specific CD8+ T cells trafficked to lymph nodes, where they were activated and tolerized by LNSCs directly presenting antigen [13].

These studies showed that stromal cells provide a unique, non-redundant contribution to peripheral tolerance. They showed that DCs are not solely responsible for deciding the fate of naïve T cells activated in secondary lymphoid organs, and ectopic expression of PTAs is not restricted to thymic stroma. By inducing tolerance to PTAs such as tyrosinase, which is not presented by peripheral DCs, and is expressed in the thymus at levels insufficient to induce tolerance [13], LNSCs provided protection from autoimmunity.

While these studies have changed our understanding of peripheral tolerance, identifying the tolerogenic cell type(s) in lymph nodes has proven elusive. Recently, this work was put into new perspective by the demonstration that tolerance induction is not limited to a single LNSC subset, as had been hypothesized [16, 17]. It was found that FRCs were the only stromal cell type expressing OVA in the iFABP-tOVA model and that these cells directly presented this antigen to stimulate naïve T cells [17]. In contrast, LECs alone were responsible for tyrosinase expression in lymph nodes and for tolerance to this antigen [16]. Tolerance induction is therefore a property of more than one cell type in the lymph node.

LNSC express an array of PTA [1]. Each stromal subset expresses characteristic PTA and, interestingly, even cells of different stromal origin express PTA from similar primary cell types [16, 17]. For example, when expressed as a PTA, Mlana (Mart1) is confined to FRC, while LECs are the only stromal cell expressing tyrosinase [16, 17]. Both Mlana and tyrosinase are products of terminally differentiated melanocytes, yet their expression as PTAs in lymph nodes is segregated. Assuming choice of PTA expression by LNSCs results from selective pressure, a convergent evolutionary drive to represent melanocytes inside lymph nodes has resulted in expression of different proteins by both FRCs and endothelium.

Tolerance induction has not been directly demonstrated for BECs or for an undefined subset of stromal cells (referred to as “double negative” or DN for stromal markers gp38 and CD31) [17, 28]. However, both subsets express PTAs[16, 17], and there is as yet no reason to suggest that these cells would not also fulfill a tolerogenic function.

The expression of PTA by diverse LNSCs is striking for a number of reasons. Firstly, it suggests that there is not a specialized tolerogenic stromal cell type present in lymph nodes; the function is shared between cells of various lineages, known (with the exception of the undefined DN subset) to directly interact with T cells (Figure 1). Second, with peripheral tolerance a confirmed function of lymphatic and potentially also blood endothelium, the mechanism could potentially also operate outside lymph nodes. This remains an open area of inquiry for the field.

Strikingly, new evidence suggests that lymph node stroma express multiple fatty acid chaperone proteins at high levels [37], which suggests that FRC-expressed iFABP may be functional. The definition of a PTA does not preclude function for an expressed protein, but is usually used to describe an antigen expressed at a low-level in primary or secondary immune organs, with highly tissue-restricted expression pattern elsewhere.

Aire and DF1

Promiscuous expression of PTAs and their direct presentation by LNSCs to naive T cells in the periphery is crucial for the induction of CD8+ T cell tolerance to certain self-antigens [12–17]. In the thymus, the transcriptional regulator autoimmune regulator Aire drives expression of a wide variety of PTAs by mTECs [6, 38], to ensure that developing thymocytes are screened for potential self-reactivity against a broad array of peripheral self-proteins [5–7, 38]. Here, Aire operates via complex molecular mechanisms that are thought to include opening of chromatin structure near transcriptionally inactive target genes, and stabilizing subsequent mRNA transcripts [39–43].

In light of its role in the thymus, it was conceivable that Aire regulated PTA expression by LNSCs. Indeed, Aire transcript was detected in stromal cell-enriched fractions of the lymph node [12]. To study these cells, a mouse strain was developed that expressed GFP-fused pancreatic protein IGRP (islet-specific glucose 6 phosphatase catalytic subunit related protein) under control of the Aire locus in a bacterial artificial chromosome [15]. The authors observed Aire transcript and nuclear protein in a population of EpCAM+MHC II+UEA-1-gp38- stromal cells within the lymph node [15].

These cells, termed eTAC (extra-thymic Aire-expressing cells) lacked expression of CD80 and CD86, two potent costimulatory molecules, and could delete transgenic T cells specific to the IGRP protein. Microarray comparison of eTAC from wild type and Aire-deficient mice revealed that Aire regulates the transcription of genes involved in antigen processing and presentation as well as a number PTA, several of which have been implicated in human diseases [15]. Intriguingly, Aire-dependent PTA in eTAC and mTEC are largely distinct [15], perhaps reflecting a non-redundant division of labor between the thymus and lymph nodes.

Although Aire was found to drive transcription of a number of PTA in eTAC [15], it is clear from recent reports that Aire does not regulate the expression of all physiologically significant PTA observed in lymph nodes [16]. LNSC-mediated tolerance to tyrosinase, for example, is Aire-independent, because LEC from Aire−/− mice directly express and present this antigen to naive CD8+ T cells [16]. Two groups have provided data suggesting that Aire expression is limited to a poorly-studied and rare DN subset of stromal cells [16, 17].

Recently a role was described for deformed epidermal autoregulatory factor 1, (DF1) in regulating PTA expression in the LNSCs of pancreatic lymph nodes of NOD mice [44]. At least two DF1 isoforms exist, and as NOD mice age, the balance of these isoforms is disrupted such that canonical DF1 is replaced with DF1 splice variant (DF1-VAR1) [44]. In contrast to DF1, DF1-VAR1 is unable to enter the nucleus to regulate PTA transcription due to the absence of a nuclear localization signal. DF1-VAR1 is able to bind to DF1, perhaps sequestering it in the cytoplasm and contributing to disease in aging NOD mice by restricting PTA expression [44]. DF1 transcripts were recently detected in each of the different LNSC populations [17]. Interestingly, it appears that Aire and DF1 might be inversely expressed in the different stromal populations [17], although the functional implications of this are unclear. The specific roles of transcriptional regulators in lymph nodes for governing PTA transcription for peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance induction remain to be elucidated.

Mechanisms of LNSC-mediated suppression

The mechanisms for LNSC suppression of CD8 T cells are unknown, beyond an association with the PD-1 / PD-L1 pathway [45]. Aire is involved in at least one [15] but not all models [16].

According to the classic model of T cell activation, to fully acquire effector function, in addition to signaling through the T cell receptor after binding peptide-loaded MHC, a T cell must receive a secondary signal, usually from stimulatory B7 family members binding CD28 (reviewed by [46]). So-called “professional” APCs (DCs, macrophages and B cells) are potent T cell activators and readily provide secondary signals after exposure to inflammatory stimuli. However, under certain circumstances, many other cell types, including LNSCs [17] are capable of upregulating these molecules. The interest in LNSCs lies with their eventual deletion, rather than initial activation of T cells. The precise mechanisms that control this fate are unclear, but LNSCs (particularly FRCs) are capable of upregulating at least some costimulatory molecules [17].

If MHC / TCR ligation occurs without an accompanying second signal, a T cell becomes either apoptotic or anergized (reviewed by [46]). Anergy also occurs following TCR signaling if the inhibitory B7 family members PD-L1 or PD-L2 bind their ligand PD-1 on T cells. PD-L1 may also affect T cell polarization [47, 48]. PD-L1 blockade was found sufficient to prevent tolerance induction in the iFABP-tOVA transgenic mouse model; T cells became activated in anti-PD-L1 treated mice, but were not subsequently tolerized or lost from the peripheral pool, and went on to induce acute inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract [45]. This finding suggests that LNSCs have the potential, albeit in the absence of PD-L1, to activate T cells.

Any role for LNSCs in inducing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells is unknown. However, LNSCs in mesenteric lymph nodes produce retinoic acid [49], which promotes the development of these important immunosuppressive cells [50]. It is therefore possible that, in addition to their role in deleting autoreactive T cells, LNSCs may contribute to tolerance through inducing regulatory lymphocyte populations.

LNSC and Inflammation

The lymph node undergoes profound changes during an inflammatory response, and can expand up to many times its original size. Stromal populations in the lymph node express TLRs associated with immune responses to viral products, which suggests a swift and innate response to pathogenic threat [17]. Treatment with the TLR3 ligand polyI:C causes broad upregulation of MHC class I and some costimulatory molecules, and the expression of PTAs changes profoundly [17]. It was shown that when FRCs are infected with an LCMV strain, the outcome for CD8 T cells is more tolerogenic, and the lymph node structure is better maintained than if FRC are not infected [51]. While this might, in some circumstances, cause progression to chronic infection, it provides a tempting additional rationale for evolution of LNSC-mediated tolerance induction: preservation of lymph node structure, to allow the mechanics of the immune response to continue unimpeded [17, 51]. However, while inflammation decidedly alters the T cell / FRC interaction [17], the in vivo outcome for T cells activated by inflamed FRCs is as yet unknown.

Other PTA-expressing stromal populations

The discovery that multiple stromal populations express PTA and induce antigen-specific tolerance raises obvious questions about stromal cell populations outside secondary lymphoid organs. Indeed, anti-inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) are commonly induced during tumor formation [52–54] and are associated with increased tumor growth and metastasis. These cells adopt a CCL21+ gp38+ FRC-like phenotype, and a decreased anti-tumor immune response [54]. Similarly, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC), which can be expanded ex-vivo from most tissues, induce tolerance or reduce inflammation to improve outcomes for GvHD, ischemia, cardiac infarction, chronic lung disease, colitis, and many other pathologies (reviewed by [55]). Indeed, some studies have suggested that CAF begin as multipotent MSC, which migrate to the tumor site in order to expand and differentiate [56]. It is unclear whether MSC migration forms the canonical pathway to CAF generation, primarily because the precise criteria required to distinguish CAF, MSC, and steady-state tissue fibroblasts in situ are not known. However, human colonic myofibroblasts exhibit a suppressive phenotype in situ and, in the absence of obvious inflammation, express PD-L1, PD-L2 and MHC class II, but lack classic costimulatory B7.1 [57] In vitro, these cells suppress CD4+ T cell proliferation similar to MSC populations [57]. Interestingly, epithelial cells from tissues other than the thymus have been shown to constitutively express PTA [58] and may play a similar tolerogenic role to MSCs. Thymic epithelial cells, of course, are well known for their expression of thousands of PTA, and play a critical, non-redundant role in central tolerance induction [5, 6].

Interestingly, chronic inflammation associated with autoimmunity, allograft rejection or infection has been associated with the presence of FRC-like cells at the site of tissue damage [59–61]. These cells express CCL19 and CCL21 and attract and arrange leukocytes into a segregated immune structure resembling a lymph node (reviewed by [62]). Notably, the generation of FRC-like cells is, in these cases, positively associated with ongoing inflammation rather than tolerance. PTA expression in these cells has not been reported.

Together, an emerging view suggests that a dampening effect on T cell proliferation is a feature common to stromal cells from many organs and tissues, but particularly mesenchymal stroma. PTA expression is not well studied in systems outside the thymus and lymph node, but tolerance under inflammatory conditions has been extensively profiled for MSC and CAF, and appears both robust and clinically significant. MSC reportedly induce tolerance using multiple mechanisms including production of suppressive nitric oxide (NO) after exposure to T cell derived IFNγ, skewing of CD4+ T cell differentiation, and induction of Tregs [63–65]. CAF also produce high levels of NO, which has been linked to increased mutagenesis of cancer cells through DNA damage [66], although chronic NO production in mice has also been associated with reduced p53 and beta catenin expression, and reduced progression to adenocarcinoma after prolonged inflammation [67]. Interestingly, conversion of CAF to FRC-like cells expressing CCL21 is associated with preferential recruitment of poorly-immunogenic leukocyte populations and an immunosuppressive microenvironment, resulting in increased tumor growth [54].

Research into reversing the anti-inflammatory effect of CAF is long-standing and ongoing, in an effort to induce tumor rejection and anti-tumor immunity. Conversely, MSCs are used for precisely this tolerogenic capacity and are expanded ex-vivo and then infused in patients to reduce inflammation in a number of clinical conditions, particularly GvHD. Finally, prevention or ablation of lymphoid organ neogenesis may assist in reducing some types of autoimmune pathology. Thus, many fields will benefit from a broader understanding of the contribution of mesenchyme-derived cells (including FRC and LEC) to tolerance induction.

Concluding remarks

The discovery of Aire and PTA expression in thymic epithelial cells radically changed our perception of central tolerance. Similarly, emerging literature suggests an exciting paradigm shift for peripheral tolerance theory, in which naïve T cells trafficking through lymph node are exposed to PTAs specifically expressed by stromal cells.

Having now been shown in multiple models, it is clear that autoimmunity can be prevented when autoreactive T cells encounter their cognate antigen presented by a LNSC. While the mechanism of action is unknown, potent tolerance induction to antigens from the gut, pancreas and skin has been convincingly demonstrated. These antigens were all ectopically expressed at low levels by resident lymph node stroma, and expression by lymph node stroma is both necessary and sufficient for tolerance induction when transgenic cognate T cells were transferred. The autoreactive T cells were activated, underwent proliferation, and were lost from the peripheral T cell pool. Residual transgenic T cells were insufficient in either number or function to cause tissue damage.

The biological and clinical implications of these recent studies are far-reaching, and range from the potentially beneficial: prevention of autoimmunity, impeding bystander T cell activation, and maintenance of the lymph node structure in the face of inflammation; to promoting deleterious tumor tolerance. Discovering the mechanisms involved and learning to harness them opens for exploration many new therapeutic corridors.

Box 1: Can DCs cross present antigen derived from LNSCs?

In the thymus, resident DCs can obtain antigen from thymic mTECs and cross-present it with high efficiency to tolerize developing thymocytes[68, 69]. This mechanism has not yet been described in lymph nodes. In the cutaneous lymph nodes of iFABP-tOVA mice, OVA expression is limited to FRCs, and resident DCs could not induce proliferation of OT-I T cells, suggesting that cross-presentation does not occur in this model[12]. Similarly, in a model used to demonstrate cross-presentation of thymic stromal-derived antigen by thymic DCs, it was also shown that splenic DCs could not cross-present nuclear OVA from splenic stromal cells [69]. However, splenic DCs were incapable of inducing any degree of T cell proliferation to nuclear OVA in this model, even when they intrinsically expressed it [69].

Box 2: Future research directions

-

-

Do LNSCs present PTAs to CD4+ T cells?

-

-

What are the mechanisms resulting in T cell deletion after being activated by LNSCs?

-

-

Can blood endothelial cells, FDCs and double negative stroma directly present PTAs to T cells?

-

-

Why are different PTAs expressed by different stromal cell types? Are there spatial, temporal or functional differences in how different stromal cell types interact with T cells?

-

-

Is migration along a stromal network sufficient for tolerance induction, or does there need to be sustained interaction between the stromal cell and the T cell?

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lohse AW, et al. Estimation of the frequency of self-reactive T cells in health and inflammatory diseases by limiting dilution analysis and single cell cloning. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:667–675. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan RS, et al. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8alpha+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science. 2003;301:1925–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.1087576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allan RS, et al. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity. 2006;25:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukacs-Kornek V, et al. The kidney-renal lymph node-system contributes to cross-tolerance against innocuous circulating antigen. J Immunol. 2008;180:706–715. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derbinski J, et al. Promiscuous gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells mirrors the peripheral self. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1032–1039. doi: 10.1038/ni723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson MS, et al. Projection of an immunological self-shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science. 2002;298:1395–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1075958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liston A, et al. Gene dosage--limiting role of Aire in thymic expression, clonal deletion, and organ-specific autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1015–1026. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson NS, et al. Most lymphoid organ dendritic cell types are phenotypically and functionally immature. Blood. 2003;102:2187–2194. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinman RM, et al. Dendritic cell function in vivo during the steady state: a role in peripheral tolerance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Toll-dependent selection of microbial antigens for presentation by dendritic cells. Nature. 2006;440:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature04596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbone FR, et al. Transfer of antigen between migrating and lymph node-resident DCs in peripheral T-cell tolerance and immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:655–658. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JW, et al. Peripheral antigen display by lymph node stroma promotes T cell tolerance to intestinal self. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:181–190. doi: 10.1038/ni1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nichols LA, et al. Deletional self-tolerance to a melanocyte/melanoma antigen derived from tyrosinase is mediated by a radio-resistant cell in peripheral and mesenteric lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2007;179:993–1003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnusson FC, et al. Direct presentation of antigen by lymph node stromal cells protects against CD8 T-cell-mediated intestinal autoimmunity. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1028–1037. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner JM, et al. Deletional tolerance mediated by extrathymic Aire-expressing cells. Science. 2008;321:843–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1159407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JN, et al. Lymph node-resident lymphatic endothelial cells mediate peripheral tolerance via Aire-independent direct antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2010;207:681–688. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher AL, et al. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells directly present peripheral tissue antigen under steady-state and inflammatory conditions. J Exp Med. 2010;207:689–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mebius RE. Organogenesis of lymphoid tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:292–303. doi: 10.1038/nri1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eikelenboom P, et al. The histogenesis of lymph nodes in rat and rabbit. Anat Rec. 1978;190:201–215. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bajenoff M, et al. Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity. 2006;25:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katakai T, et al. A novel reticular stromal structure in lymph node cortex: an immuno-platform for interactions among dendritic cells, T cells and B cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1133–1142. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katakai T, et al. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells construct the stromal reticulum via contact with lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:783–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sixt M, et al. The conduit system transports soluble antigens from the afferent lymph to resident dendritic cells in the T cell area of the lymph node. Immunity. 2005;22:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munoz-Fernandez R, et al. Follicular dendritic cells are related to bone marrow stromal cell progenitors and to myofibroblasts. J Immunol. 2006;177:280–289. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunn MD, et al. A B-cell-homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt's lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391:799–803. doi: 10.1038/35876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hase H, et al. BAFF/BLyS can potentiate B-cell selection with the B-cell coreceptor complex. Blood. 2004;103:2257–2265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Shikh ME, et al. Activation of B cells by antigens on follicular dendritic cells. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link A, et al. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1255–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luther SA, et al. Coexpression of the chemokines ELC and SLC by T zone stromal cells and deletion of the ELC gene in the plt/plt mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12694–12699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ansel KM, et al. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature. 2000;406:309–314. doi: 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf E, et al. Lymph node chemokines promote sustained T lymphocyte motility without triggering stable integrin adhesiveness in the absence of shear forces. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1076–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomei AA, et al. Fluid flow regulates stromal cell organization and CCL21 expression in a tissue-engineered lymph node microenvironment. J Immunol. 2009;183:4273–4283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warnock RA, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:205–216. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denucci CC, et al. Integrin function in T-cell homing to lymphoid and nonlymphoid sites: getting there and staying there. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:87–109. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willard-Mack CL. Normal structure, function, and histology of lymph nodes. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:409–424. doi: 10.1080/01926230600867727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vezys V, et al. Expression of intestine-specific antigen reveals novel pathways of CD8 T cell tolerance induction. Immunity. 2000;12:505–514. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokuda N, et al. Identification of FABP7 in fibroblastic reticular cells of mouse lymph nodes. Histochem Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00418-010-0754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsey C, et al. Aire deficient mice develop multiple features of APECED phenotype and show altered immune responses. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11:397–409. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liiv I, et al. DNA-PK contributes to the phosphorylation of AIRE: importance in transcriptional activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Org T, et al. The autoimmune regulator PHD finger binds to non-methylated histone H3K4 to activate gene expression. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:370–376. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oven I, et al. AIRE recruits P-TEFb for transcriptional elongation of target genes in medullary thymic epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8815–8823. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01085-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koh AS, et al. Aire employs a histone-binding module to mediate immunological tolerance, linking chromatin regulation with organ-specific autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15878–15883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808470105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abramson J, et al. Aire's partners in the molecular control of immunological tolerance. Cell. 2010;140:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yip L, et al. Deaf1 isoforms control the expression of genes encoding peripheral tissue antigens in the pancreatic lymph nodes during type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1026–1033. doi: 10.1038/ni.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynoso ED, et al. Intestinal tolerance is converted to autoimmune enteritis upon PD-1 ligand blockade. J Immunol. 2009;182:2102–2112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leitner J, et al. Receptors and ligands implicated in human T cell costimulatory processes. Immunol Lett. 2010;128:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang SC, et al. PD-L1 and PD-L2 have distinct roles in regulating host immunity to cutaneous leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:58–64. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Latchman YE, et al. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10691–10696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammerschmidt SI, et al. Stromal mesenteric lymph node cells are essential for the generation of gut-homing T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2483–2490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coombes JL, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller SN, et al. Viral targeting of fibroblastic reticular cells contributes to immunosuppression and persistence during chronic infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15430–15435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702579104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Egeblad M, et al. The fibroblastic coconspirator in cancer progression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:383–388. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shields JD, et al. Induction of lymphoidlike stroma and immune escape by tumors that express the chemokine CCL21. Science. 2010;328:749–752. doi: 10.1126/science.1185837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyndall A, Uccelli A. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells for autoimmune diseases: teaching new dogs old tricks. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:821–828. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coffelt SB, et al. The pro-inflammatory peptide LL-37 promotes ovarian tumor progression through recruitment of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3806–3811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900244106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinchuk IV, et al. PD-1 ligand expression by human colonic myofibroblasts/fibroblasts regulates CD4+ T-cell activity. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1228–1237. 1237, e1221–1222. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dooley J, et al. Lessons from thymic epithelial heterogeneity: FoxN1 and tissue restricted gene expression by extrathymic, endodermally derived epithelium. J Immunol. 2009;183:5042–5049. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Timmer TC, et al. Inflammation and ectopic lymphoid structures in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissues dissected by genomics technology: identification of the interleukin-7 signaling pathway in tissues with lymphoid neogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2492–2502. doi: 10.1002/art.22748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baddoura FK, et al. Lymphoid neogenesis in murine cardiac allografts undergoing chronic rejection. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shomer NH, et al. Helicobacter-induced chronic active lymphoid aggregates have characteristics of tertiary lymphoid tissue. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3572–3577. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3572-3577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:205–217. doi: 10.1038/nri1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ren G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalez MA, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental colitis by inhibiting inflammatory and autoimmune responses. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:978–989. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez-Rey E, et al. Human adult stem cells derived from adipose tissue protect against experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut. 2009;58:929–939. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.168534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3256–3276. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang R, et al. Induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase: a protective mechanism in colitis-induced adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1122–1130. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gallegos AM, Bevan MJ. Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1039–1049. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koble C, Kyewski B. The thymic medulla: a unique microenvironment for intercellular self-antigen transfer. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1505–1513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]