Abstract

Defective endosperm* (De*)-B30 is a dominant maize (Zea mays) mutation that depresses zein synthesis in the developing endosperm. The mutant kernels have an opaque, starchy phenotype, malformed zein protein bodies, and highly increased levels of binding protein and other chaperone proteins in the endosperm. Immunoblotting revealed a novel α-zein protein in De*-B30 that migrates between the 22- and 19-kD α-zein bands. Because the De*-B30 mutation maps in a cluster of 19-kD α-zein genes, we characterized cDNA clones encoding these proteins from a developing endosperm library. This led to the identification of a 19-kD α-zein cDNA in which proline replaces serine at the 15th position of the signal peptide. Although the corresponding gene does not appear to be highly expressed in De*-B30, it was found to be tightly linked with the mutant phenotype in a segregating F2 population. Furthermore, when the protein was synthesized in yeast cells, the signal peptide appeared to be less efficiently processed than when serine replaced proline. To test whether this gene is responsible for the De*-B30 mutation, transgenic maize plants expressing this sequence were created. T1 seeds originating from the transformants manifested an opaque kernel phenotype with enhanced levels of binding protein in the endosperm, similar to De*-B30. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the De*-B30 mutation causes a defective signal peptide in a 19-kD α-zein protein.

A number of mutations have been identified that affect storage protein synthesis in maize (Zea mays) endosperm (for review, see Coleman and Larkins, 1998). The mutant kernels typically have a starchy endosperm texture and low density, both of which are thought to be associated with the reduced synthesis of the prolamin storage proteins, or zeins. When placed on a light box, endosperm of these mutants does not transmit light, i.e. it is opaque, whereas that of normal, wild-type kernels is vitreous and translucent. Recessive mutations that produce such an opaque kernel phenotype are traditionally classified as “opaque” (e.g. opaque1-15), whereas semidominant opaque mutations are called “floury” (e.g. floury1-3). There are, in addition, several dominant opaque mutations, defective endosperm* (De*)-B30 and Mucuronate (Mc; Soave et al., 1979; Soave and Salamini, 1984). The basis of the relationship between an opaque kernel phenotype and zein synthesis is not well understood. Although several of these mutants have a reduced zein content and show altered expression of specific types of zein genes, the degree to which zein synthesis is reduced among them is variable (Hunter et al., 2002). For example, in o1, zein synthesis is barely affected. Generally, these mutations result in increased expression of genes associated with physiological stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR; Kaufman, 1999) during endosperm development.

Because of their influence on zein synthesis and the nature of their pleiotropic effects on other genes expressed in the endosperm, the genetic defects responsible for opaque and floury mutations have been postulated to involve regulatory proteins (Soave and Salamini, 1984; Motto et al., 1988; Schmidt, 1993). However, this hypothesis has only been confirmed in the case of the o2 mutation, which corresponds to a defective bZIP transcription factor that regulates, among other genes, a subset of α-zein coding sequences (Schmidt, 1993). The only other mutant gene identified that causes an opaque endosperm phenotype is fl2, which was found to correspond to a defective signal peptide in a 22-kD α-zein protein (Lopes et al., 1994; Coleman et al., 1995, 1997; Gillikin et al., 1997).

To increase our understanding of the factors that contribute to a vitreous kernel phenotype, we have focused our research on the characterization of mutations that cause a starchy, opaque kernel phenotype. Here, we describe the identification and characterization of the genetic defect responsible for the De*-B30 mutation. This mutant was described as preferentially decreasing the synthesis of 22-kD α-zein proteins (Soave et al., 1979; Soave and Salamini, 1984), and in double mutants, o2 was epistatic to De*-B30 (Marocco et al., 1991). The mutation mapped on the short arm of chromosome 7, where it was linked with a number of genes encoding 19-kD α-zein proteins (Soave et al., 1979). The contiguous genomic DNA sequences comprising all α-zein genes at this locus were recently determined in the B73 inbred and were shown to contain six genes of the z1B-1 subfamily (Song and Messing, 2002).

Like fl2 and Mc, the De*-B30 mutation is associated with the increased synthesis of a protein originally identified as b-70 (Soave and Salamini, 1984). This protein was later shown to be a homolog of a heat shock protein 70 protein, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized binding protein (BiP; Boston et al., 1991; Marocco et al., 1991). BiP is increased about 10-fold over wild type in the fl2 mutant, but is increased only around 5-fold in Mc and De*-B30 (Marocco et al., 1991). The induction of BiP synthesis in these mutants correlates with the relative reduction in zein accumulation and accompanies changes in protein body morphology (Lending and Larkins, 1992; Zhang and Boston, 1992). Based on the map location of De*-B30 and the nature of the phenotype it creates, we hypothesized the mutation corresponds to a defective 19-kD α-zein protein. Upon cloning and sequencing a representative population of 19-kD α-zein cDNA clones from W64ADe*-B30, we identified a gene that is genetically linked with the De*-B30 mutation and that recreates the De*-B30 phenotype in transgenic maize endosperm.

RESULTS

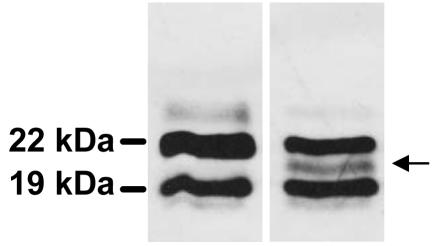

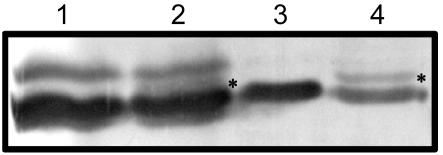

In contrast to wild-type protein bodies, those in developing endosperm of De*-B30 are irregular and lobed, not unlike those found in the maize fl2 mutant (Zhang and Boston, 1992). To investigate if this abnormal protein body morphology is associated with an unusual zein protein, extracts from B37+ and B37De*-B30 protein bodies were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue R. This comparison failed to reveal specific differences in the predominant α-, β-, γ-, and δ-zein proteins (data not shown); however, when these proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal antiserum that recognizes the 22- and 19-kD α-zeins, a novel protein band was detected that migrated between the 22- and 19-kD α-zeins (Fig. 1). This protein had an apparent Mr approximately 2 kD larger than the 19-kD α-zein protein group.

Figure 1.

Immunoblotting identifies a novel α-zein linked with the De*-B30 mutation. Protein body proteins (20 μg lane-1) from B37+ and B37De*-B30 were separated by 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. The membrane was probed with antiserum that recognized 19- and 22-kD α-zeins; their positions are denoted on the left and the identification of the novel α-zein protein is shown by the arrow on the right.

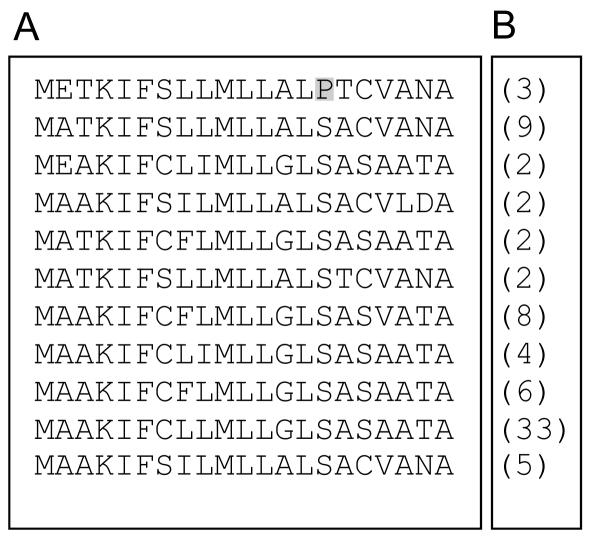

Because the De*-B30 mutation is genetically linked with a cluster of 19-kD α-zeins (Soave et al., 1979; Soave and Salamini, 1984), we hypothesized that it might correspond to a defective 19-kD α-zein precursor protein. Accordingly, we screened a De*-B30 cDNA library with a 19-kD α-zein cDNA probe (GenBank accession no. M12146) using a moderate hybridization stringency to ensure cross-hybridization among different members of this large gene family (Song and Messing, 2002; Woo et al., 2001). The cDNA library was constructed using poly(A)+ RNA from 16 d after pollination (DAP) developing endosperm of an inbred line created by introgressing the B37De*-B30 mutation into W64A (Hunter et al., 2002). After plaque purification, 100 clones were obtained that hybridized to the 19-kD α-zein probe. A preliminary analysis of these clones was done by restriction enzyme digestion to distinguish between related sequences; this led to the identification of 76 clones that were selected for DNA sequencing. These clones (GenBank accession nos. CF752004-CF752078) identified 11 distinct mRNA sequences; their frequency and deduced signal peptide sequences are shown in Figure 2. Almost one-half of them (33 of 76) appeared to correspond to a single gene accession sequence (GenBank no. M12143), whereas the other 10 sequences were represented by clones that were much less abundant, i.e. isolated two to six times, suggesting that the genes encoding them are expressed at a lower level.

Figure 2.

Signal peptide amino acid sequences and frequency of 19-kD α-zeins isolated from a W64ADe*-B30 cDNA library. A, The amino acid sequences of signal peptides for 19-kD α-zein mRNAs were deduced from cDNAs obtained from a 16 DAP De*-B30 endosperm library. B, The number in parenthesis refers to the frequency of the sequence among 76 independent 19-kD α-zein cDNA clones that were analyzed (GenBank accession nos. CF752004-CF752078).

DNA sequence analysis of the cDNA clones revealed they are all members of the 19-kD α-zein gene family and that they encode full-length precursor protein sequences. Their deduced amino acid sequences showed a high degree of conservation in signal peptide structure, consistent with von Heijne rules: they contain a 21-amino acid sequence with a short, positively charged amino-terminal region, a central hydrophobic region, and a more polar carboxy-terminal region containing the signal peptidase cleavage site (von Heijne, 1985; Chou, 2001). Nine of the 21 amino acids are invariant and, with one exception, the amino acid differences at the other 11 positions occur in more than one signal peptide sequence and are generally conservative. The exception is residue 15 in the first signal peptide shown in Figure 2A, where Pro replaces Ser. This change is predicted to alter the position where signal peptidase would cleave, such that it would occur between amino acids 19 and 20 rather than 21 and 22 (Hidden Markov models; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-2.0). Consequently, this amino acid difference could affect the proteolytic processing of the molecule.

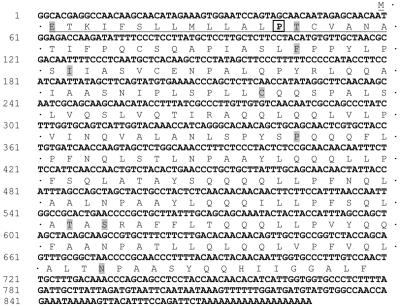

The complete nucleotide and amino acid sequence of the variant cDNA, which we designated the 19-kD15Pα-zein (GenBank accession no. AY434688), is shown in Figure 3. The gene encoding the mRNA corresponds to the z1B-1 subfamily of 19-kD α-zeins defined by Song and Messing (2002). It is 98% identical to α-zein cDNA A20, identified by accession number V01476 (Geraghty et al., 1982), which is part of a bacterial artificial clone (BAC) contig that comprises all members of the z1B-1 gene subfamily in B73. This BAC contig (GenBank accession no. AF546188) is found on the short arm of chromosome 7 (bin 7.01-7.02), and it is closely linked with the De*-B30 mutation.

Figure 3.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence of the 19-kD15P α-zein deduced from a full-length cDNA clone (GenBank accession no. AY434688). The signal peptide is underlined and Pro 15 is enclosed in a box. Amino acids that differ from those in the closely related A-20 19-kD α-zein (GenBank accession no. V01476) are contrasted in gray.

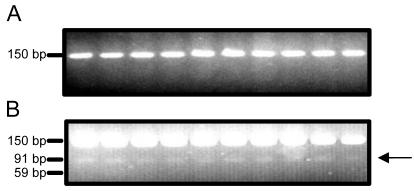

As a consequence of the nucleotide difference associated with the Pro/Ser variation in its signal peptide, the 19-kD15Pα-zein gene contains an Ear I restriction enzyme site. This nucleotide sequence polymorphism allowed us to evaluate the genetic linkage of this gene with the opaque endosperm phenotype of the De*-B30 mutant. We designed oligonucleotide primers (19 upstream and 19 downstream) to amplify a 150-nucleotide sequence encompassing the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and the signal peptide sequence of the z1B-1 19-kD α-zein gene subfamily members. The 19-kD α-zein gene sequences from DNA of 30 W64A+ and 30 W64ADe*B30 homozygotes were PCR amplified and the products were digested with Ear I. An analysis of a subset of wild-type and mutant individuals (10 of each) is shown in Figure 4. DNA from the wild-type kernels produced a single fragment of 150 nucleotides (Fig. 4A), whereas that from the De*-B30 mutants produced the 150-nucleotide band, a band of 91 bp, and a very faint band of 59 bp (Fig. 4B). The small DNA fragments obtained after Ear I digestion of the 19-kD15Pα-zein sequence were never observed among the wild-type PCR products, and they were always recovered from the PCR products of the mutant kernels. The exact number of z1B-1 19-kD α-zein gene subfamily members in W64ADe*-B30 is not known, but it is likely equal to or larger than in B73 (Song and Messing, 2002). Therefore, the low abundance of the 91- and 59-bp fragments reflects that the19-kD15Pα-zein gene is only one member of the z1B-1gene subfamily and perhaps the fact that portions of short PCR products are sometimes refractory to restriction enzyme digestion (Turbett and Sellner, 1996).

Figure 4.

The gene encoding the 19-kDS15P α-zein cosegregates with the De*-B30 mutation. Genomic DNA was isolated from homozygous wild-type and De*-B30 seedlings, and a 150-bp sequence spanning the 5′-UTR and signal peptide sequence was amplified by PCR using the 19 upstream and 19 downstream primers described in “Materials and Methods.” The wild-type (A) and De*-B30 (B) PCR products were digested with the Ear I restriction enzyme and were separated by electrophoresis in 3% (w/v) agarose gel. Ear I cleaves the 19-kDS15P PCR product into two fragments of 91 bp (arrow) and 59 bp, the latter of which is not visible in this image.

We previously showed that yeast cells transformed with zein coding sequences can synthesize and process these proteins, leading to the formation of accretions similar to zein protein bodies (Kim et al., 2002). Consequently, yeast provided a convenient way to test if the Pro/Ser variation in the signal peptide sequence affected processing by signal peptidase. A point mutation was made in the19-kD15Pα-zein cDNA sequence that changed Pro-15 to Ser, creating the 19-kDS15Pα-zein construct. Both sequences were then cloned into the pGPD426 vector and transformed into yeast cells. Yeast cultures expressing each of these genes were grown to an OD of 0.8, lysed, and the proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Figure 5 shows an immunoblot of the gel after treatment with antiserum that recognizes the 19- and 22-kD α-zein proteins. The samples in lanes 1 and 2 are controls, showing zein extracts from W64A+ and W64ADe*-B30, respectively. In this immunoblot, the novel α-zein band in De*-B30 is not well resolved (Fig. 5, lane 2); it appears as a dark shadow that is marked by an asterisk between the 19- and 22-kD α-zein bands. Expression of the 19-kDS15Pα-zein in yeast resulted in a single protein band that comigrated with the mature 19-kD α-zein proteins (Fig. 5, lane 3). However, expression of the 19-kD15Pα-zein cDNA sequence yielded two polypeptides (Fig. 5, lane 4), one that migrated with the mature 19-kD α-zeins and one (marked with an asterisk) that migrated at the position of the novel protein band in De*-B30. These results suggest that in yeast, at least, the signal peptide of the 19-kD15Pα-zein is inefficiently processed, resulting in the accumulation of an α-zein precursor.

Figure 5.

The mutant 19-kD15P α-zein is inefficiently processed in yeast cells. Proteins were extracted from wild-type and De*-B30 maize endosperms, and from yeast cells expressing genes encoding the 19-kD15P and 19-kDS15P α-zeins. After separation by 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and transfer to a nylon membrane, the proteins were reacted with antiserum recognizing the 19-kD α-zeins. Lane 1, W64A wild type; lane 2, De*-B30; lane 3, yeast expressing the 19-kDS15P α-zein; lane 4, yeast expressing the 19-kD15P α-zein.

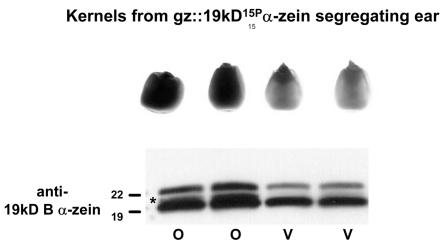

To obtain additional molecular genetic evidence regarding whether or not the19-kD15P α-zein is responsible for the De*-B30 mutation, we transformed maize with the cDNA sequence encoding this protein. As we were unsure of the promoter of the gene encoding this protein, we used the transcriptional regulatory sequences of the 27-kD γ-zein, which provides high levels of expression in developing maize endosperm (Ueda and Messing, 1991; Russell and Fromm, 1997), to construct a chimeric gene (gz::19kD15P α-zein). Transformation of this sequence into maize cells was performed by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer using immature embryos of an F1 hybrid created by crossing the highly transformable hybrid of A188 and B73 (Hi-II; Armstrong et al., 1991) and the Pioneer inbred line PHR03. Forty-six independent transgenic events were regenerated into plants and were self-pollinated upon silking. Visual analysis of kernels from mature T0 ears showed segregation for a strong opaque phenotype in most (24) of these events. This phenotype was similar to the dominant opaque phenotype observed in W64ADe*-B30, as shown in Figure 6. To test for the presence of the protein encoded by gz::19kD15P α-zein, endosperm protein extracts from the vitreous and opaque kernels were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to a membrane, and treated with a specific 19-kD B α-zein antiserum (Woo et al., 2001). As shown in the bottom of Figure 6, only the opaque kernel extracts contained an immunocrossreactive band (marked by an asterisk) that migrated at the position of the 19-kD15P α-zein protein. In general, this band did not resolve distinctly from the major 19-kD α-zein band, but there was no evidence of a protein this size in the vitreous kernels. The opaque phenotype of these kernels is consistent with the hypothesis that the 19-kD15P α-zein is responsible for the De*-B30 mutant phenotype.

Figure 6.

Expression of the 19-kD15P α-zein in transgenic maize plants results in an opaque kernel phenotype. The top panel shows a representative sample of segregating opaque (o) and vitreous (v) kernels from a transgenic gz::19kD15P α-zein ear (line 1532.231.2.9.1, genetic background Hi-II/PHR03). The bottom panel shows an immunoblot analysis of endosperm proteins from these kernels. The proteins were separated by 10% to 20% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and probed using a 19-kD B α-zein antibody. The positions of 22- and 19-kD α-zein proteins that crossreacted with the antibody are denoted at the left of the figure and the novel 19-kD15P α-zein is shown by the asterisk.

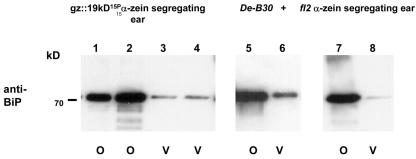

Previous studies of the De*-B30 mutant showed it manifests the UPR, as evidenced by the overexpression of BiP and other chaperone transcripts and proteins in the endosperm (Boston et al., 1991; Marocco et al., 1991; Hunter et al., 2002). To evaluate this phenotype in transgenic gz::19kD15P α-zein events, additional immunoblotting was performed with a plant BiP-specific antibody (Anderson et al., 1994). Figure 7 (panel 1) shows that the level of BiP expression was greatly increased in opaque compared with vitreous kernels from a heterozygous gz::19kD15P α-zein T0 ear. This level of BiP induction was very similar to that observed in W64ADe*-B30 (Fig. 7, panel 2) and transgenic maize endosperm expressing the fl2 α-zein gene (Fig. 7, panel 3), which encodes a defective signal peptide (Coleman et al., 1995, 1997).

Figure 7.

The ER chaperone BIP is highly induced in gz::19kD15P α-zein-expressing endosperms, similar to W64ADe*-B30 and transgenic fl2-expressing endosperm. Total endosperm protein extracts from opaque (o) and vitreous (v) seed from the transgenic gz::19kD15P α-zein line 1532.231.2.9.1 (left), an opaque (o) and vitreous (v) kernel of a W64ADe*-B30 F2 ear (panel), and an opaque (o) and vitreous (v) kernel from a transgenic ear segregating for the fl2 α-zein (line 236300; right) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a plant BiP-specific antibody. Equal amounts of samples were loaded into each lane based on an endosperm dry weight basis.

DISCUSSION

De*-B30 was described by Salamini and colleagues (Soave et al., 1979; Soave and Salamini, 1984) as a dominant mutation that maps on the short arm of chromosome 7, where it was linked with several genes encoding 19-kD α-zein proteins. It was noted that the mutation caused a preferential decrease in the synthesis of 22-kD α-zein proteins, and in double mutants, o2 was epistatic to De*-B30 (Marocco et al., 1991). We did not observe a qualitative reduction in 22-kD α-zeins when the mutation was crossed into W64A (Hunter et al., 2002); consequently, this effect of the mutation may be related to its expression in the B37 inbred background where it was originally described. The observation that o2 is epistatic to De*B30 is perhaps a consequence of involvement of the O2 protein in the transcriptional control of some 19-kD α-zein genes. Partial suppression of 19-kD α-zein gene expression in o2 mutant backgrounds has been observed (Hunter et al., 2002; R. Jung, unpublished data). We measured a marked reduction in α-zein synthesis and an increased accumulation of nonzein proteins in De*-B30, which are consistent with the higher Lys content of this mutant (Balconi et al., 1998; Hunter et al., 2002).

Evidence from the experiments described in this study is consistent with the hypothesis that the De*B30 mutation results from a defective signal peptide in the 19-kD15Pα-zein protein that we identified. Protein body morphology in the De*-B30 mutant is abnormal, not unlike fl2, which was shown to result from a defective signal peptide in a 22-kD α-zein protein (Coleman et al., 1997). The observation of a novel α-zein in De*-B30 approximately 2 kD larger than the mature 19-kD α-zeins is consistent with a defective signal peptide, and this hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that De*-B30 is genetically linked with a cluster of 19-kD α-zeins (Soave and Salamini, 1984). The near sequence identity of the gene encoding the 19-kD15P α-zein and that corresponding to the A20 α-zein cDNA identified by GenBank accession number V01476 (Geraghty et al., 1982), which occurs in the z1B-1 19-kD α-zein gene cluster on BAC contig AF546188, which is linked with De*-B30 on the short arm of chromosome 7 (Song et al., 2002), is consistent with these genes being alleles. Based on the well-documented structural features of signal peptides (von Heijne, 1985), substitution of Pro for Ser at the 15th position of the signal peptide is predicted to alter its structure, such that the site of signal peptide cleavage would be altered. The results from our experiments with yeast are consistent with the hypothesis that whereas a Pro substitution for Ser at position 15 does not prevent signal peptide cleavage, it nevertheless affects the efficiency of the process. We can only speculate that signal peptidase cleavage would be similarly or perhaps even more severely affected in maize endosperm cells.

We obtained strong genetic and molecular evidence that the gene encoding the 19-kD15P α-zein is responsible for the De*-B30 mutation. First, there was absolute genetic linkage between the opaque kernel phenotype of De*-B30 and the allele encoding the 19-kD15P α-zein gene in a large F2 population. Unfortunately, there is only one De*-B30 mutation, therefore we could not compare the sequence of this gene with other alleles of De*-B30. Nevertheless, a BLAST search of public databases (all GenBank+RefSeq Nucleotide+EMBL+DDBJ+DB sequences, including expressed sequence tag, Sequence Tagged Sites, and Genome Survey Sequences sequences, July 23, 2003) and of the proprietary DuPont-Pioneer corn genome and expressed sequence tag database failed to identify any other 19-kD α-zein gene or transcript encoding Pro at the 15th position of the signal peptide.

Perhaps the best evidence that the gene encoding the 19-kD15P α-zein is responsible for the De*-B30 mutation comes from the phenotype of transgenic kernels expressing this gene. In gz::19kD15P α-zein transgenic events, there was tight linkage between the opaque kernel phenotype and expression of the 19-kD15P α-zein protein. Furthermore, the segregation ratios of vitreous and opaque kernels from these ears were consistent with a primarily dominant form of gene action being responsible for the starchy endosperm phenotype. This phenotype is unlikely to result from the ER-overload response (Pahl and Baeuerle, 1997; Cudna and Dickson, 2003), and opaque kernels are usually not observed due to transgenic overexpression of maize seed proteins encoded by wild-type alleles (R. Jung, unpublished data). Like the fl2 and Mc mutants, transgenic maize kernels expressing the 19-kD15P α-zein gene were associated with an increased synthesis of BiP (Boston et al., 1991; Marocco et al., 1991), which was dramatically increased over wild-type levels. Based on mRNA transcript profiling (Hunter et al., 2002; B.C. Gibbon, unpublished data), we recently found the expression of a number of genes associated with the UPR (Kaufman, 1999) is significantly up-regulated in fl2, Mc, and De*-B30. The induction of BiP synthesis in these mutants is associated with a reduction in zein synthesis and accompanies changes in protein body morphology (Lending and Larkins, 1992; Zhang and Boston, 1992).

De*-B30 and fl2 share many phenotypic features, and consequently, it is not surprising that they involve defective signal peptides in α-zein proteins. The 19- and 22-kD α-zeins are structurally very similar (Argos et al., 1982), and they are very hydrophobic proteins that are found in the center of zein protein bodies (Lending and Larkins, 1989). We predict that these proteins are similarly dispersed throughout the center of the protein body, although immunolocalization experiments with 19- and 22-kD α-zein-specific antibodies have not been done. Nevertheless, in situ hybridization of mRNAs encoding 19- and 22-kD α-zein proteins revealed similar patterns of temporal and spatial expression in the endosperm, which is consistent with this hypothesis (Woo et al., 2001). Consequently, the biochemical effects of synthesizing an α-zein that does not properly fold into its native protein structure would be manifest throughout most of the starchy endosperm.

One surprising observation regarding the properties of these mutants is the fact that De*-B30 is dominant, whereas fl2 is a semidominant mutation (Jones, 1978; Soave et al., 1979; DiFonzo et al., 1980). The gene encoding the fl2 protein appears to be much more highly expressed than that encoding De*-B30. This is reflected at the protein level, where the fl2 product is easily detectable with Coomassie Blue staining after SDS-PAGE, whereas the De*-B30 protein can only be detected by immunoblotting. The difference in resolution could be related to the fact that the 19-kD15P α-zein is compressed between the 22- and 19-kD zein bands, which makes it more difficult to observe. However, it also appears there are marked differences in the level of mRNA transcripts encoding these proteins. Recent studies have shown that the gene at the fl2 locus is one of the most highly expressed 22-kD α-zeins (Song et al., 2001; Hunter et al., 2002; Song and Messing, 2003). Based on the frequency of cDNAs corresponding to the 19-kD15P α-zein in the W64A background, this mRNA represented only about 4% of the 19-kD α-zein transcripts. Consequently, the 19-kD15P α-zein gene does not appear to be highly expressed.

How does De*-B30 create a dominant mutant phenotype when it corresponds to an α-zein that is expressed at a lower level than fl2? Perhaps the answer relates to the mechanism by which zeins assemble into protein bodies. We recently reported experiments in which zein interactions were investigated using the yeast two-hybrid system (Kim et al., 2002). These experiments showed differences in the apparent strength of interactions of the 22-kD α-zeins and the 19-kD α-zeins with one another and with other types of zein proteins. The results are suggestive that the spatial distribution of α-zeins within the protein body may not be random, and perhaps interactions between specific types of zeins are important for protein body organization (Lending and Larkins, 1989). If this were the case, alterations in the synthesis and deposition of certain types of α-zeins might have a more pronounced affect on protein body structure than others. An alternative explanation for the difference in penetrance of fl2 and De*-B30 mutant phenotypes is that the fl2 signal peptide may not be recognized by the signal peptidase, resulting in the accumulation of substantial amounts of precursor protein. On the other hand, the De*-B30 signal peptide might be recognized by the signal peptidase, but inefficiently cleaved. This would result in the large, multiprotein signal peptidase complex remaining attached to the zein precursor, which, in turn, could have a greater impact on the interaction between the amino acid sequence of the mature zein protein and the chaperone proteins that interact with it. As a consequence, the signal peptidase would remain in this complex rather than separating from it, as occurs during the normal translocation of secreted proteins.

We currently have a very limited understanding of the genetic defects that give rise to an opaque kernel phenotype. In the case of the fl2, De*-B30, and Mc (C.S. Kim, unpublished data) mutations, the starchy endosperm phenotype is clearly linked to structural defects in zein proteins that lead to abnormal protein body structure and the UPR. However, insight regarding the biochemical basis for the opaque endosperm phenotype will require identification and characterization of additional opaque mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maize (Zea mays) Mutant Analysis by SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

The B37De*-B30 mutant was provided to us by Dr. Francesco Salamini (Instituto Biosintesi Vegetali, Bergamo, Italy). The mutation was introgressed into the W64A inbred by six generations of backcrossing and two generations of selfing (Hunter et al., 2002). Protein bodies were isolated from B37+ and B37De*-B30 kernels harvested 18 DAP as previously described (Gillikin et al., 1997). Protein bodies were quantified with the bicinchoninic acid Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) after solubilization in 1% (w/v) SDS. Samples were adjusted to 0.5 mg mL-1 with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) and were boiled for 5 min. For immunoblot analysis, proteins were electroblotted from 10% (w/v) SDS-polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose using a semidry blotting apparatus (Trans-Blot SD; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the buffer system described by Harlow and Lane (1988). Filters were probed with polyclonal antibodies against α-zeins at a 1:10,000 dilution. Antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G at 1:10,000 dilutions, respectively. Immunoblots were developed with detection reagents provided with the SuperSignal CL-HRP Substrate System (Pierce).

mRNA Preparation, and cDNA Library Construction and Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from kernels of W64ADe*-B30 at 16 DAP by the CsCl density gradient method of Sambrook et al. (1989). Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from total RNA with a Poly(A) Quik mRNA kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and cDNA was synthesized with the ZAP Express cDNA Synthesis kit (Stratagene). Based on the manufacturer's instructions, the cDNA was made double stranded, blunt-ended, ligated to Eco R1 adapters, digested with XhoI, and size fractionated. The cDNA was then directionally cloned into the ZAP Express vector and packaged with a Gigapack III Gold cloning kit (Stratagene). After infection of Escherichia coli MRF' cells, a primary library of about 4 × 106 independent clones was obtained. The library was amplified to a titer of approximately 8 × 109 pfu mL-1. The cDNA library (approximately 3 × 105 pfu) was screened with a 19-kD α-zein (GenBank accession no. M12146) probe that was radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci mmol-1) using a Rediprime II random prime kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Filter hybridization and washing were done at a moderate stringency (final wash of 0.2× SSC and 0.1% [w/v] SDS at 60°C) to maximize cross-hybridization of the 19-kD α-zein cDNA sequences. Selected clones were excised in vivo from the ZAP Express Vector using the ExAssist helper phage according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). Inserts in the pBK-CMV phagemid vector were sequenced using T3 (5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGG-3′) and T7 (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′) primers. Sequence alignment and analysis were performed with MultAlin (http://prodes.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/multalin.html) and ExPAsy software (http://us.expasy.org/tools/dna.html). GenBank accession numbers for the sequences are as follows: 19-kD15Pα-zein gene (GenBank accession no. AY434688); other 19-kD α-zeins (GenBank accession nos. CF752004-CF752078).

Linkage Analysis of the 19-kDS15P α-Zein with the De*-B30 Mutation

A genetic cosegregation analysis was done to determine the linkage of the 19-kD15P α-zein gene with the De*-B30 mutation. Thirty homozygous normal and De*-B30 kernels were germinated and DNA was extracted from seedling leaves with hexadecyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide (Saghai-Maroof et al., 1984). To PCR amplify a conserved 150-bp region spanning the 19-kD α-zein mRNA's 5′-UTR and signal peptide sequences (48 nucleotides before and 99 nucleotides after the ATG codon), we designed primer 19 upstream (5′-CAACAAGCAACATAGAAAGTGGA-3′) and primer 19 downstream (5′-GGAAGCTATAGGAGCTTGTGAGCATTG-3′). The reaction was initiated by denaturing genomic DNA at 94°C for 5 h, followed by 35 cycles of PCR as follows: 94°C for 1 min; 58°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 30 s. The final cycle was extended at 72°C for 5 h. The DNA products were digested with the Ear I endonuclease for 12 h and were separated by electrophoresis in 3% (w/v) agarose gel.

In Vitro Mutagenesis of the 19-kD15P α-Zein and Expression of Zein Genes in Yeast

Yeast cells were used to compare processing of the 19-kD15P α-zein signal peptide with that of a comparable protein in which Pro-15 was replaced with Ser. A recombinant gene with the Ser/Pro replacement was constructed as follows: the signal peptide region of the 19-kD15P α-zein was amplified with primer Z19upE1 (5′-GGAATTCCAACAAGCAACATAGAAAGTGGA-3′) and primer Z19CTdown (5′-GTTAGCAACACATGTAGAAAGAGCAAG-3′). The remainder of the 19-kD α-zein-coding region was amplified with primer Z19CTup (5′-ACATGTGTTGCTAACGCGACAATTTTC-3′) and primer Z19downX1 (5′-CCGCTCGAGCGGCTAAAAGAGGGCACCACC-3′). The two PCR products were annealed and reamplified with primers Z19upE1 and Z19downX1 and cloned into pGPD426 after digestion with EcoRI and XhoI. The authentic recombinant clone was verified by DNA sequence analysis. For expression of the 19-kD15P and 19-kDS15P α-zeins in yeast cells, PCR was performed with primers Z19upE1 and Z19down X1 and the products were inserted into pGPD426 at the EcoR1 and XhoI sites; the correct nucleotide sequence of the clones was then verified. The W303 (MATα ade2-1, his3-11, trp1-1, ura3-1, leu2-3, and leu2-112) yeast strain was used for expression of the 19-kD α-zein proteins as previously described (Kim et al., 2002). Protein was extracted from yeast cells as described by Yaffe and Schatz (1984), and immunoblotting was performed according to Sambrook et al. (1989). A 19-kD α-zein primary antiserum was used at a 1:5,000 dilution (Hunter et al., 2002). Goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphataseconjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma, St. Louis) were used at a 1:30,000 dilution.

Expression of the 19-kD15P α-Zein in Transgenic Maize Endosperm

The relationship between the 19-kD15P α-zein gene and the De*-B30 mutant phenotype was evaluated by expressing the cDNA in transgenic maize endosperm. The transformation vector (pHP19437) was constructed from a derivative of pSB1 (Japan Tobacco, Higashibara, Iwata, Japan), which contains cauliflower mosaic virus 35S-BAR between the T-DNA borders as a selectable marker gene (D'Halluin et al., 1992) and an endosperm-specific 27-kD γ-zein expression cassette. The 19-kD15P α-zein-coding sequence was PCR amplified from the cDNA clone and was inserted between the 27-kD γ-zein promoter and terminator sequences (Lopes et al., 1994) of the expression cassette using standard cloning techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989).

A. tumefaciens-mediated maize transformation was accomplished following the method of Zhao et al. (2001). Briefly, freshly isolated 10 DAP F1 immature embryos of Hi-II (Armstrong et al., 1991) crossed to PHR03 (a Pioneer proprietary inbred) were incubated with the recombinant A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404 (Japan Tobacco). The A. tumefaciens and immature embryos were cocultivated for 3 d at 20°C and for 3 d at 28°C. All culture steps were performed in darkness. The embryos were then subcultured in Bialophos-containing medium (3 mg L-1) for selection of transgenic events. Putative transgenic calli were regenerated, matured somatic embryos were germinated and propagated in culture tubes, and they were then moved to the greenhouse where they were grown to maturity as described by Gordon-Kamm et al. (2002). Fertile transgenic plants were self-pollinated and the progeny kernels were scored for endosperm phenotype by visual inspection with a light box. Protein extraction and immunodetection were carried out as described by Woo et al. (2001). Briefly, total endosperm protein was extracted from flour with SDS sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) containing 100 mm dithiothreitol. Proteins were separated using precast 10% to 20% (w/v) Tris-Gly SDS gels (Bio-Rad), electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and treated with a 19-kD B α-zein-specific antibody (Woo et al., 2001) or with a plant BiP-specific antibody (SPA-818; Stressgen Biotechnologies, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeff Gillikin for technical support with the De*-B30 protein analysis. We also thank Pam Gunderson and Kimberly Glassman for vector construction, Regina Higgins and Dr. Jerry Ranch for corn transformation, and Shifu Zhen for expert greenhouse support. We would also like to thank Dr. Paul Anderson and Dr. Mitch Tarczynski who encouraged this research.

This work was supported by the Department of Energy (grant no. DE-96ER20242 to B.A.L.), by Pioneer Hi-Bred (to B.A.L.), and by the Department of Energy (grant no. DE-FG02-00ER15065 to R.S.B.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.031310.

References

- Anderson JV, Li QB, Haskell DW, Guy CL (1994) Structural organization of the spinach endoplasmic reticulum-luminal 70-kilodalton heat-shock cognate gene and expression of 70-kilodalton heat shock genes during cold acclimation. Plant Physiol 104: 1359-1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argos P, Pedersen K, Marks MD, Larkins BA (1982) A structural model for maize zein proteins. J Biol Chem 257: 9976-9983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CL, Green CM, Phillips RL (1991) Development and availability of germplasm with high Type II culture formation response. Maize Genet Coop News Lett 65: 92-93 [Google Scholar]

- Balconi C, Berardo N, Reali A, Motto M (1998) Variation in protein fractions and nitrogen metabolism of developing normal and opaque endosperm mutants of maize. Maydica 43: 195-203 [Google Scholar]

- Boston RS, Fontes EBP, Shank BB, Wrobel RL (1991) Increased expression of the maize immunoglobulin binding protein homology b-70 in three zein regulatory mutants. Plant Cell 3: 497-505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K-C (2001) Using subsite coupling to predict signal peptides. Protein Eng 14: 75-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CE, Clore AM, Ranch JP, Higgins R, Lopes MA, Larkins BA (1997) Expression of a mutant α-zein creates the floury2 phenotype in transgenic maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 7094-7097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CE, Larkins BA (1998) Prolamins of maize. In R Casey, PR Shewry, eds, Seed Proteins. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 109-139

- Coleman CE, Lopes MA, Gillikin JW, Boston RS, Larkins BA (1995) A defective signal peptide in the maize high-lysine mutant floury2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 6828-6831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudna RE, Dickson AJ (2003) Endoplasmic reticulum signaling as a determinant of recombinant protein expression. Biotechnol Bioeng 81: 56-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Halluin K, De Block M, Denecke J, Janssens J, Leemans J, Reynaerts A, Botterman J (1992) The bar gene as selectable and screenable marker in plant engineering. Methods Enzymol 216: 415-426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFonzo N, Fornasari E, Salamini F, Reggiani R, Soave C (1980) Interaction of maize mutants floury-2 and opaque-7 with opaque-2 in the synthesis of endosperm proteins. J Hered 71: 397-402 [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty D, Messing J, Rubenstein I (1982) Sequence analysis and comparison of cDNAs of the zein multigene family. EMBO J 1: 1329-1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillikin JW, Zhang F, Coleman CE, Bass HW, Larkins BA, Boston RS (1997) A defective signal peptide tethers the floury2 zein to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Plant Physiol 114: 345-352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Kamm W, Dilkes BP, Lowe K, Hoester G, Sun X, Ross M, Church CB, Farrell J, Hill P, Maddock S et al. (2002) Stimulation of the cell cycle and maize transformation by disruption of the plant retinoblastoma pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11975-11980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Hunter BG, Beatty MK, Singletary GW, Hamaker BR, Dilkes BP, Larkins BA, Jung R (2002) Maize opaque endosperm mutations create extensive changes in patterns of gene expression. Plant Cell 14: 2591-2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA (1978) Effects of Floury-2 on zein accumulation and RNA metabolism during maize endosperm development. Biochem Genet 16: 27-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ (1999) Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev 13: 1211-1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CS, Woo Y-M, Clore AM, Burnett RJ, Carneiro NP, Larkins BA (2002) Zein protein interactions, rather than the asymmetric distribution of zein mRNAs on endoplasmic reticulum membranes, influence protein body formation in maize endosperm. Plant Cell 14: 655-672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lending CR, Larkins BA (1989) A model for protein body formation in corn: immunolocalization of zeins in developing maize endosperm by light and electron microscopy. Plant Cell 1: 1011-1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lending CR, Larkins BA (1992) Effect of the floury2 locus on protein body formation during maize endosperm development. Protoplasma 171: 123-133 [Google Scholar]

- Lopes MA, Coleman CE, Kodrzycki R, Lending CR, Larkins BA (1994) Synthesis of an unusual α-zein protein is correlated with the phenotypic effects of the floury2 mutation in maize. Mol Gen Genet 245: 537-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marocco A, Santucci A, Cerioli S, Motto M, Di Fonzo N, Thompson R, Salamini F (1991) Three high-lysine mutations control the level of ATP-binding HSP70-like proteins in maize endosperm. Plant Cell 3: 507-515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motto M, Maddaloni M, Ponziani G, Brembilla M, Marotta R, Di Fonzo N, Soave C, Thompson R, Salamini F (1988) Molecular cloning of the o2-m5 allele of Zea mays using transposon marking. Mol Gen Genet 212: 488-494 [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL, Baeuerle PA (1997) The ER-overload response: activation of NF-κB. Trends Biochem Sci 22: 63-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DA, Fromm ME (1997) Tissue-specific expression in transgenic maize of four endosperm promoters from maize and rice. Transgenic Res 6: 157-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen R, Allard RW (1984) Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 8014-8018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Schmidt RJ (1993) Opaque-2 and zein gene expression. In DPS Verma, ed, Control of Plant Gene Expression. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 337-355

- Soave C, Salamini F (1984) Organization and regulation of zein genes in maize endosperm. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B 304: 341-347 [Google Scholar]

- Soave C, Viotti A, DiFonzo N, Salamini F (1979) Maize prolamine: synthesis and genetic regulation. In Seed Protein Improvement in Cereals and Grain Legumes, Vol. 1. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria, pp 165-174 [Google Scholar]

- Song R, Llaca V, Messing J (2001) Mosaic organization of orthologous sequences in grass genomes. Genome Res 12: 1549-1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song R, Messing J (2002) Contiguous genomic DNA sequence comprising the 19-kD zein gene family from maize. Plant Physiol 130: 1626-1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RT, Messing J (2003) Gene expression of a gene family in maize based on noncollinear haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9055-9060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbett GV, Sellner LN (1996) Digestion of PCR and RT-PCR products with restriction endonucleases without prior purification or precipitation. Promega Notes Magazine 60: 23 [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T, Messing J (1991) A homologous expression system for cloned zein genes. Theor Appl Genet 82: 93-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G (1985) Signal sequences: the limits of variation. J Mol Biol 184: 99-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo Y-M, Hu DW-N, Larkins BA, Jung R (2001) Genomics analysis of genes expressed in maize endosperm identifies novel seed proteins and clarifies patterns of zein gene expression. Plant Cell 13: 2297-2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MP, Schatz G (1984) Two nuclear mutations that block mitochondrial protein import in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 4819-4823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Boston RS (1992) Increases in binding protein (BiP) accompany changes in protein body morphology in three high-lysine mutants of maize. Protoplasma 171: 142-152 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZY, Gu W, Cai T, Tagliani L Hondred D, Bond D, Schroeder S, Rudert M, Pierce D (2001) High throughput genetic transformation mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens in maize. Mol Breeding 8: 323-333 [Google Scholar]