Abstract

Study Objective

To compare acceptability of the vaginal contraceptive ring to that of oral contraceptive pills.

Design

Randomized, cross-over, 6-month study.

Setting

Urban family planning clinic for young low-income patients.

Participants

Sexually active females aged 15–21 years (n = 130).

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to use the vaginal ring or oral contraceptive pills for an initial study interval of three 28-day cycles, followed by three cycles of the alternate method.

Main Outcome Measures

Participants completed surveys about method use, acceptability, and side effects at baseline, after three cycles, and after six cycles. We analyzed study data using ANOVA models for cross-over designs.

Results

We did not detect higher compliance with the ring as compared to oral contraceptive pills (P = 0.176), although overall approval of the ring was significantly higher on several items measured, including liked using method (P = 0.015), would recommend it to friends (P = 0.012), and not as hard to remember to use method correctly (P ≤ 0.000). Participants were less worried about health risks while using the ring (P = 0.006), but reported that the ring was more likely to interfere with sex than the pill (P ≤ 0.001) and that sex partners liked the pill (P = 0.034). Most women did not report bothersome side effects with either method.

Conclusions

Adolescent and young women showed favorable acceptability of the vaginal contraceptive ring compared to oral contraceptive pills.

Keywords: Vaginal ring, Adolescents, Acceptability of hormonal contraception

Introduction

NuvaRing®, approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2001, is a flexible, two-inch ring made of ethinyl vinyl acetate that is inserted in the vagina as a contraceptive method. The ring releases on average 120 mcg etonogestrel and 15 mcg ethinyl estradiol over a 24-hour period. The vaginal ring is labeled for cyclic use: after insertion, it is left in place in the vagina for three weeks and then removed and discarded. After seven days, a new vaginal ring is inserted. The vaginal ring may have important advantages for sexually active adolescents and young women at high risk for unintended pregnancy, as this group experiences higher “typical use” pregnancy rates with available contraceptive methods than do older women1,2 and is most likely to use oral contraceptive pills and condoms3 which require high user compliance. By comparison, the characteristics of the vaginal ring may make consistent use simpler, easier, or involve fewer bothersome side effects, thus enhancing contraceptive coverage for this population. However, clinicians may be reluctant to recommend the vaginal ring for adolescent use, given the lack of data and concerns about acceptability of a method that requires vaginal insertion.

Clinical trials have demonstrated a failure rate for the vaginal ring of 0.7%, a discontinuation rate of 15%, high acceptability, and low levels of side effects.4 A study of genital symptoms, signs, exam, and laboratory findings for ring and oral contraceptive pill use found that satisfaction was significantly higher (P ≤ 0.001) for vaginal ring use than for oral contraceptive use and plans to use the ring in the future were reported by 50% of the study participants, compared to 28% who planned to use pills.5 In a study comparing continuous use of the vaginal ring, 77%–92% of participants reported being “satisfied with using the ring.”6 The mean age of women in these studies, however, was 28,4 25,5 and 286 years. The study reported in this paper sought to assess acceptability of the vaginal contraceptive ring compared to that of oral contraceptive pills among sexually active adolescents and young women aged 15 to 21 years.

Materials and Methods

This study followed participants who used two different methods of hormonal contraception for a three-cycle duration for each method, and compared measures of method use and acceptability. Contraceptive products used in the study were the vaginal ring (NuvaRing®) and an oral contraceptive pill (Ortho-Cyclen®) that contains the estrogen and progestin combination—ethinyl estradiol 35 mcg and norgestimate 0.25 mg. We choose a standard oral contraceptive that many women use rather than a very low dose pill (i.e. Alesse®), to see a comparison between the vaginal ring and a widely used oral contraceptive pill. The study compared participants’ assessment of side effects following use of the vaginal ring to assessments following use of oral contraceptive pills, although the measures that pertain to hormonal side effects are limited by the difference in hormonal content. We hypothesized that the young women in our study would report higher satisfaction with the vaginal ring than with oral contraceptive pills.

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco. Participants were enrolled and followed between April 2003 and February 2004 at an urban family planning clinic for low income young people. Female patients were eligible for recruitment if they attended the clinic requesting contraception, were found medically appropriate for use of a hormonal contraceptive, wanted to use a hormonal contraceptive method, were between the ages of 15 and 21, wanted to participate in the study, and consented to enroll in the study. Inclusion criteria also included having at least one regular menstrual period preceding enrollment or being within seven days post induced abortion. Study participants had to speak either English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria were use of hormonal contraception during the month preceding enrollment, or contraindications to use of combined hormonal contraception.

Of the 230 women screened, 100 were not enrolled in the study, mainly due to recent use of hormonal contraceptives (n = 26), ineligible age (n = 13), not sexually active (n = 12), and irregular menses (n = 6). Other eligibility reasons included positive pregnancy test (n = 4), migraines (n = 3), recent birth (n = 1), breastfeeding (n = 1), obesity (n = 1), medical problems (n = 1). Many women were not interested after receiving information on the study (n = 21), and others were lost before enrollment (n = 9), lived outside of study area (n = 1), or the recruitment period ended (n = 1).

A total of 130 subjects were enrolled and randomized. Half were assigned to use the ring for the first three cycles of study, and half to use oral contraceptive pills; after three cycles, each participant switched (crossed over) to use the other method for the second three cycles of her participation. Method use was not blinded. Study participants were randomized to their initial method at the time of enrollment. The envelope sequence was provided by the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, using a random number generator in blocks.

Participants completed surveys using computer-assisted self-interviewing software at the time of enrollment (baseline), after completing the first three cycle series, and after completing the second three cycle series of method use. Computer assisted interviewing has been shown to be effective for questions on sensitive topics.7,8 In addition, a telephone survey was conducted one month after study completion to determine what method, if any, the participant was using in the month after study participation. Questions for the survey were adapted from the National Survey for Family Growth and previously reported surveys.9 Our instrument was similar in content and array of items with the Acceptability Questionnaire whose formal validation in Europe was recently published.10 It included questions on demographics, contraceptive decision making, sexual behavior, consistency and correctness of method use, side effects, method acceptability, and satisfaction. In addition to completing the surveys, the date of each subject’s last menstrual period, blood pressure, and weight were recorded and a urine sample was tested for pregnancy at baseline, after the first three-cycle series, and after the second three-cycle series. Prior to conducting the study, the computer surveys were pilot tested for comprehension and logistics with 20 patients seeking services at the study site.

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to enrollment in the study. A waiver of parental consent was approved by the Committee on Human Research for enrollment of minors because the study posed minimal risks, and all study participants were seeking contraceptive services at the clinic. Under California law, minors may consent to their own confidential reproductive medical and contraceptive care. Study subjects received a total of $90 as compensation for the time required for study participation.

Study Measures

We collected subject information including race/ ethnicity, previous pregnancies and births, age at first intercourse, use of hormonal contraception and condoms. To assess the correctness and consistency of method use, participants were asked about their method use at the time of the survey, i.e. whether they had the ring in place or, for pill use, whether they had taken one the previous day. Women completing a survey during their “week off” the pill or ring were categorized as compliant. To assess ease of method use, participants were asked whether they agreed or disagreed that the method was easy to use, whether they were worried about using the method correctly, and whether it was hard to remember to use their method correctly. To assess attitudes and concerns about method effectiveness and side effects, participants were asked whether they were worried about pregnancy while using the method, whether they were confident the method would prevent pregnancy, and whether they were worried about health risks. To assess method influence on sexuality, participants were asked whether the method interfered with sex, the sex partner liked the method, or the participant liked the way she felt when using method. To assess overall method acceptance and satisfaction, participants were asked whether they liked using the method, would recommend the method to friends, and would use the method again in the future.

The surveys included a series of questions about possible side effects, and after each three-cycle series asked whether they were better, worse or no different: amount of blood in period, cramping in period, pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS), weight, acne, headaches, nausea, discharge, discomfort, moodiness, depression and sex drive.

Data Analysis

We compared demographic and reproductive characteristics of participants randomized to the two groups (oral contraceptives first vs. vaginal ring first). We conducted an attrition analysis, by comparing the subjects lost to follow-up to those who completed the study on a series of characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, previous use of hormonal methods, condom use, age of first intercourse and study arm. We used chi-square statistics to compare categorical variables, Fisher’s exact tests if there were few observations, and t-tests to compare continuous variables.

We presented frequencies of method acceptance and satisfaction, side effects and health concerns by method. For statistical testing of the acceptability and side effects outcome measures, we conducted analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a 2×2 crossover study. The models tested the treatment, period and sequence effects. An omnibus measure of separability tested for the independence between treatment and carryover effects.11 A carryover effect is a measure of the effect of the treatment assigned in period one on the results in period two. Outcome analyses were performed on participants completing the study. Participants with missing data on the outcome (due to skipped survey items) were not included in the analysis of that outcome. All analyses were performed using Stata (8.0). The study was designed as a pilot effort to develop and validate measures of acceptability, method use, and preferences among young women, with the sample size based on the available budget.

Results

The baseline characteristics of participants are presented by randomization at enrollment in Table 1. Sixty-seven (51.5%) of subjects were assigned at baseline to oral contraceptive pills and 63 (48.5%) to the vaginal ring. Subjects ranged from 15 to 21 years, with a mean age of 17.1 (sd = 1.5). The sample population was diverse with 38% African-American, 34% Latina, 10% Asian, 6% White and 12% multi-racial/other. One quarter of the sample had experience with hormonal contraception, and slightly more reported a previous pregnancy. Six percent had given birth. The mean age of first intercourse was 15 years. About one quarter reported multiple partners within the past three months, and 63% reported condom use at last sexual intercourse. There were no significant differences in these characteristics by first method at randomization.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by randomization at enrollment: Vaginal ring and oral contraceptive pills

| Baseline Characteristics | Vaginal Ring n = 63 48.5% |

Oral Contraceptive Pills n = 67 51.5% |

Total N = 130 100% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (sd) | 17.1 (1.5) | 17.1 (1.6) | 17.1 (1.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African American | 23 (36.5) | 26 (38.8) | 49 (37.7) |

| Latina | 24 (38.0) | 20 (29.9) | 44 (33.8) |

| White | 3 (4.8) | 5 (7.5) | 8 (6.1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6 (9.5) | 7 (10.4) | 13 (10.0) |

| Multi/other | 7 (11.1) | 9 (13.4) | 16 (12.3) |

| Education (Highest level), n (%) | |||

| Below high school | 38 (60.3) | 41 (61.2) | 79 (60.8) |

| High school/GED | 14 (22.2) | 12 (17.9) | 26 (20.0) |

| Above high school | 11 (17.5) | 14 (20.9) | 25 (19.2) |

| Past use hormonal contraception, n (%) | 15 (23.8) | 17 (25.4) | 32 (24.6) |

| Previous pregnancy, n (%) | 17 (27.0) | 18 (26.9) | 35 (26.9) |

| Previous birth, n (%) | 1 (1.6) | 7 (10.5) | 8 (6.2) |

| Age of first intercourse, mean (sd) | 15.0 (1.4) | 15.2 (1.5) | 15.1 (1.4) |

| Multiple partners, past 3 mths, n (%) | 16 (25.4) | 15 (22.4) | 31 (23.8) |

| Condom at last intercourse, n (%) | 42 (66.7) | 40 (59.7) | 82 (63.1) |

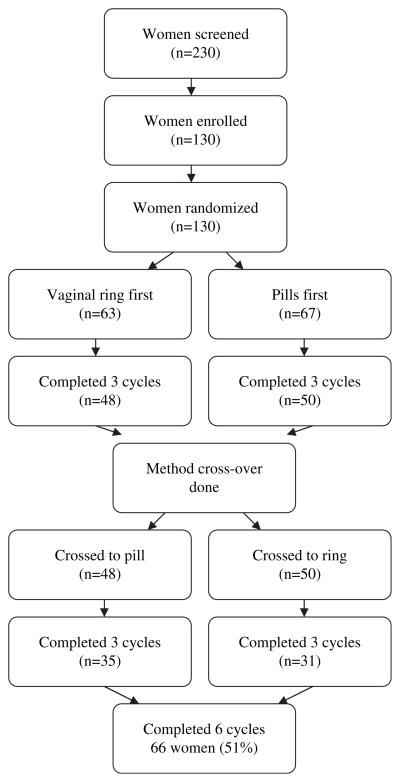

Figure 1 provides a flow chart. Ninety-eight participants (75%) completed the three-month follow-up visit, 66 participants (51% of baseline sample) completed the six-month follow-up visit. Seventy-three participants completed the one-month post study call. An attrition analysis showed no difference in the age of the sample between subjects lost to follow-up and those who completed the study six-month visit (P = 0.831), no difference in the racial/ethnic composition of the sample (P = 0.856), and no difference in previous pregnancy (P = 0.443), prior use of hormones (P = 0.362), condom use at last intercourse (P = 0.394), or age of first sexual intercourse (P = 0.263).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart.

A total of 12 participants were lost to follow-up or moved out of the area over the course of their study enrollment and 44 participants were discontinued prior to their completion of all four interviews. Reasons for discontinuation were: receiving a positive pregnancy test, desire to switch contraceptive method, failure to return for follow-up interviews within the required four weeks from scheduled date, or the reporting of intolerable side effects and desire to discontinue study method. Adverse events reported during the study included 13 pregnancies (four during or following an interval assigned as vaginal ring use, and nine during or following an interval assigned as oral contraceptive pill use).

There was no statistically significant difference in method compliance reported following vaginal ring use and that reported following oral contraceptive use. Forty-nine percent (n = 31) of ring users reported having their ring in place and 64 percent (n = 43) of pill users reported taking their method, and ANOVA results showed that the treatment order effect was in-significant (P = 0.176). Of the incompliant ring users, most reported they stopped using it (n = 18), only 1 reported she forgot it, and 10 gave ‘other’ as the reason. Of the pills users, 10 stopped using it, 8 reported they forgot, and 7 gave ‘other’ as the reason. The series of measures of correct method use of the ring compared to the pill, as well as acceptability measures, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Acceptability measures for the vaginal ring compared to oral contraceptive pills: Frequencies and Anova results

| Method Acceptability | Vaginal Ring (n=63) | Oral Contraceptive Pills (n=67) | F-statistic┼ | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Correct method use | ||||

| Method compliance | 31 (49.2) | 43 (64.2) | 1.88 | 0.176 |

| Method easy to use | 50 (79.4) | 40 (60.0) | 3.79 | 0.057 |

| Worried about using method correctly | 24 (38.1) | 30 (44.8) | 1.01 | 0.319 |

| Hard to remember to use correctly | 9 (14.3) | 39 (58.2) | 27.1 | 0.000*** |

| Pregnancy & health concerns | ||||

| Worried about pregnancy using method | 18 (28.6) | 23 (34.3) | 1.32 | 0.255 |

| Confident method prevents pregnancy | 44 (69.8) | 52 (77.6) | 1.39 | 0.244 |

| Worried about health risks | 20 (31.7) | 36 (53.7) | 8.14 | 0.006** |

| Sexuality | ||||

| Method doesn’t interfere w/ sex | 48 (76.2) | 63 (94.1) | 12.1 | 0.001*** |

| Sex partner liked method | 38 (60.3) | 54 (80.6) | 4.71 | 0.034* |

| Overall approval | ||||

| Liked using method | 41 (65.1) | 32 (47.8) | 6.28 | 0.015* |

| Liked way felt when using method | 42 (66.7) | 33 (49.2) | 6.86 | 0.011* |

| Would recommend method to friends | 44 (69.8) | 37 (55.2) | 6.77 | 0.012** |

| Would use method in the future | 41 (65.1) | 39 (58.2) | 0.98 | 0.327 |

F-statistic compares treatment effect of the vaginal ring compared to the oral contraceptive pill. Model controls for sequence effect (intersubjects) and period effect (intrasubjects), as well as treatment effect (intrasubject).

P ≤ 0.050.

P ≤ 0.010.

P ≤ 0.001.

Results from analysis of variance showed several statistically significant differences related to vaginal ring and oral contraceptive use. A measure of correct method use showed participants found it more difficult to remember to use pills correctly: Only 14% of participants reported that it was difficult to remember to use the ring method correctly, while 58% did after pill use (P < 0.001). Participants were equally confident about pregnancy prevention with both methods, but were more worried about health risks with the pill than with the ring (54% v. 32%; P = 0.006). However, participants were also more likely to report that their method did not interfere with sex following pill use than ring use (94% compared to 76%, P < 0.001), and that their male sexual partner liked the method (81% v. 60%, P < 0.05).

Overall method approval and acceptability were higher following vaginal ring use than following oral contraceptive pills use on most measures, including liked using method (65% v. 48%, P = 0.015), liked how felt when using method (67% v. 49%; P = 0.011) and would recommend method to friends (70% v. 55%, P < 0.010). The difference between the vaginal ring and the pill was not significant for would use method in future, however (65% v. 58%, P = 0.327). There were no significant period effects or sequence effects for any measures other than would recommend method to friends, which tended to get more favorable responses in the first period of the study, controlling for treatment order. Results showed that the treatment was estimated to be 29.3% independent of the carry-over effects.

Reported side effects are in Table 3. Few participants reported that potential side effects were better or worse following use of either method. However, the ANOVA results did show a significant difference in worsening of weight (P = 0.007), headache (P = 0.012), and moodiness (P = 0.027) problems following pill use compared to the proportion who reported worsening following vaginal ring use. There were no significant differences in worsening or improvement in the amount of menstrual blood loss, menstrual cramping, premenstrual symptoms, acne, vaginal discharge or sex drive.

Table 3.

Reports of side effects following 3 cycles of ring use and 3 cycles of pill use: Frequencies and ANOVA results

| Health Measures | Vaginal ring (n=63) | Pills (n=67) | F-statistic┼ | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bothersome side effects | 2.98 | 0.090 | ||

| Better | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.5) | ||

| No difference | 55 (87.3) | 50 (74.6) | ||

| Worse | 7 (11.1) | 16 (23.9) | ||

| Amount of blood in period | 0.60 | 0.441 | ||

| Better | 9 (14.3) | 11 (16.4) | ||

| No difference | 47 (74.6) | 39 (58.2) | ||

| Worse | 7 (11.1) | 11 (16.4) | ||

| Cramping in periods | 0.49 | 0.488 | ||

| Better | 5 (7.9) | 8 (11.9) | ||

| No difference | 48 (76.2) | 45 (67.2) | ||

| Worse | 10 (15.9) | 14 (20.9) | ||

| PMS | 1.13 | 0.293 | ||

| Better | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.0) | ||

| No difference | 55 (87.3) | 51 (76.1) | ||

| Worse | 6 (9.5) | 12 (17.9) | ||

| Weight | 7.87 | 0.007** | ||

| Better | 9 (14.3) | 4 (6.0) | ||

| No difference | 46 (73.0) | 36 (53.7) | ||

| Worse | 8 (12.7) | 27 (40.3) | ||

| Acne | 0.08 | 0.785 | ||

| Better | 6 (9.5) | 11 (16.4) | ||

| No difference | 56 (88.9) | 47 (70.1) | ||

| Worse | 1 (1.6) | 9 (13.4) | ||

| Headaches | 6.78 | 0.012* | ||

| Better | 2 (3.2) | 3 (4.5) | ||

| No difference | 57 (90.5) | 47 (70.5) | ||

| Worse | 4 (6.3) | 17 (25.4) | ||

| Nausea | – | – | ||

| Better | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | ||

| No difference | 58 (92.1) | 50 (74.6) | ||

| Worse | 5 (7.9) | 16 (1.5) | ||

| Discharge | – | – | ||

| Better | 2 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No difference | 46 (73.0) | 53 (79.1) | ||

| Worse | 15 (23.8) | 14 (20.9) | ||

| Moodiness | 5.06 | 0.027* | ||

| Better | 4 (6.3) | 4 (6.0) | ||

| No difference | 50 (79.4) | 40 (59.7) | ||

| Worse | 9 (14.3) | 23 (34.3) | ||

| Depression | – | – | ||

| Better | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.0) | ||

| No difference | 56 (88.9) | 58 (86.6) | ||

| Worse | 7 (11.1) | 5 (7.5) | ||

| Sex drive | 0.57 | 0.454 | ||

| Better | 10 (15.8) | 11 (10.4) | ||

| No difference | 52 (82.5) | 49 (73.1) | ||

| Worse | 1 (1.6) | 7 (10.4) |

Model controls for effects of sequence (intersubjects), period (intrasubjects), as well as treatment.

P ≤ 0.050.

P ≤ 0.010.

One month after study completion, 73 subjects responded to the telephone survey about the method they chose at the end of the study. Thirty-eight percent (n = 28) reported that they had chosen to use the vaginal contraceptive ring, 26% (n = 19), had chosen the pill, 16% the patch, 3% Depo-Provera®, 5.5% condoms, and 11% no method.

Discussion

At the initiation of the study the experienced clinicians at the clinic site, not unlike providers involved in the evaluation of earlier ring prototypes two decades ago,12 were unsure about whether their younger clinic patients would find a vaginal method acceptable. Results here, however, were similar to a favorable level of satisfaction reported for use among older women,4–6 and demonstrate a willingness among adolescents, 15 to 21 years, to use a method that is inserted vaginally. The participants using the ring were also more likely to like the way they felt when using the method and would be more likely to recommend the method to friends. Previous studies have not shown acceptability of the ring among this age group.

Study participants reported that the vaginal ring was easier to remember to use correctly than oral contraceptive pills; however, we might also have expected to find higher compliance with the vaginal ring in the study because the method did not require daily adherence. While very few of the participants forgot to use the ring (n = 1), as compared to the pill (n = 8), more participants reported they stopped using the ring than the pill during their assigned cycles. Study participants were more likely to report that the oral contraceptive pills did not interfere with sex and that their sex partner liked the pill as compared to vaginal ring use. We do not know, however, whether the female partners stopped the ring for these reasons or others, and additional research is needed on method continuation of the vaginal ring among adolescents.

Our findings did show that not only is use of the vaginal contraceptive ring feasible for adolescents and young women, but that its attributes may have advantages that have not previously been identified—including lower likelihood of reporting worry about health risks after using this method compared to oral contraceptive pills. Concerns about health risks with hormonal methods often account for low method uptake or discontinuation, so the reports that participants were less worried about health risks with the use of the vaginal ring could be promising. Participants also had a lower likelihood of reporting worsened problems with weight or headaches; but hormonal side effects have to be interpreted with caution, because any differences between the methods may well result from the differential hormonal content of the ring and the pill tested, rather than from the method type.

The findings of the study are limited by other aspects of the study design and a high attrition rate. Although we did not find significant differences in the characteristics of participants who discontinued the study prematurely and those who completed the full study, future research is needed to confirm results and to test acceptability in different patient groups. The duration of the study did not allow us to see to what extent the method satisfaction expressed by participants would translate into continued use; prospective studies that last one year or longer will give a better indication of pregnancy protection. It is possible that results here were biased because the participants were “by definition” interested in trying a new method. It would be reasonable to assume that those individuals who most liked oral contraceptives would be less likely than those unenthusiastic about oral contraceptive use to enroll in a study of a new method. Similarly, in a culture that expects “new” to be “better,” it is likely that any new option might be initially perceived to be superior. Also, participants were motivated enough to be seeking contraceptive care, were interested in trying a new method, and confident enough to agree to be research participants. Results here, therefore, might not be the same for other groups of young women.

Ease of method use has been a focus of attention in contraceptive research because of the possibility that improving this characteristic for new contraceptive technologies may help improve adherence and continuation, and thus overall effectiveness. Further research is indicated to compare acceptability, side effects, and preferences among adolescents and young women for the vaginal ring and other available hormonal options including the contraceptive patch, injectables, and implants.

References

- 1.Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, Rickerr VI, et al. Contraceptive outcomes among adolescents prescribed Norplant implants versus oral contraceptives after one year of use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:586. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zibners A, Cromer BA, Hayes J. Comparison of continuation rates for hormonal contraception among adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1999;12:90. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(00)86633-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alan Guttmacher Institute. Facts In Brief: Contraceptive Use. Alan Guttmacher Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roumen FJ, Apter D, Mulders TM, et al. Efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of a novel contraceptive vaginal ring releasing etonogestrel and ethinyl oestradiol. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:469. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veres S, Miller L, Burington B. A comparison between the vaginal ring and oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:555. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136082.59644.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller L, Verhoeven CH, Hout J. Extended regimens of the contraceptive vaginal ring: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:473. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175144.08035.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders GD, Owens DK, Padian N, et al. A computer-based interview to identify HIV risk behaviors and to assess patient preferences for HIV-related health states. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl/Med Care. 1994:20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Wijgert J, Padian N, Shiboski S, et al. Is audio computer-assisted self-interviewing a feasible method of surveying in Zimbabwe? Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:885. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosher WD. Design and operation of the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak A, de la Loge C, Abetz L. Development and validation of an acceptability and satisfaction questionnaire for a contraceptive vaginal ring, NuvaRing. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:245. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratkowsky DA, Evans MA, Alldredge JR. Cross-over experiments: design, analysis, and application. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer B, Jones V, Elstein M. The acceptability of the contraceptive ring. Br J Fam Plann. 1986;12:82. [Google Scholar]