Abstract

AIM: To investigate the histological origin of pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) in Chinese women.

METHODS: The clinical and pathological data were reviewed for 35 women with PMP, and specimens of the peritoneal, appendiceal and ovarian lesions of each patient were examined using the PV-6000 immunohistochemistry method. Antibodies included cytokeratin (CK)7, CK20, mucin (MUC)-1, MUC-2, carbohydrate antigen (CA)-125, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR).

RESULTS: Abundant colloidal mucinous tumors were observed in the peritoneum in all 35 cases. Thirty-one patients had a history of appendectomy, 28 of whom had mucinous lesions. There was one patient with appendicitis, one whose appendix showed no apparent pathological changes, and one with unknown surgical pathology. Ovarian mucinous tumors were found in 24 patients. The tumors were bilateral in 13 patients, on the right-side in nine, and on the left side in two. Twenty patients had combined appendiceal and ovarian lesions; 16 of whom had undergone initial surgery for appendiceal lesions. Four patients had undergone initial surgery for ovarian lesions, and relapse occurred in these patients at 1, 11, 32 and 85 mo after initial surgery. Appendiceal mucinous tumors were found in each of these four patients. Thirty-three of the 35 patients showed peritoneal lesions that were positive for CK20 and MUC-2, but negative for CK7, MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR. The expression patterns in the appendix and the ovary were similar to those of the peritoneal lesions. In one of the remaining two cases, CK20, CK7 and MUC-2 were positive, and MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR were negative. The ovaries were not resected. The appendix of one patient was removed at another hospital, and no specimen was evaluated. In the other case, the appendix appeared to be normal during surgery, and was not resected. Peritoneal and ovarian lesions were negative for CK20, MUC-2, CK7, MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR.

CONCLUSION: Most PMP originated from the appendix. Among women with PMP, the ovarian tumors were implanted rather than primary. For patients with PMP, appendectomy should be performed routinely. The ovaries, especially the right ovaries should be explored.

Keywords: Pseudomyxoma peritonei, Peritoneum, Tumor origin, Ovary, Appendix, Immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare disease that was first described in association with a mucinous tumor of the ovary in 1884[1]. It is characterized by dissemination of voluminous jelly-like mucus on the peritoneal surface. Benign or malignant epithelial cells may be found in the mucinous deposit. Its etiology and pathological origin are not yet fully understood to date. It is reported in the literature that PMP often originates from the appendix[2-10]; however, a third to a half of PMP cases are accompanied by ovarian mucinous tumors in women. It has been controversial over the years whether the ovarian lesions in patients with PMP are primary or metastatic or implanted from the appendix. Most studies have indicated that PMP associated with ruptured mucinous lesions originates from the appendix. However, some authors consider that PMP originates from the ovaries[1,11-14].

Cytokeratin (CK)7 is a specific marker of primary ovarian epithelial tumor, which is rarely expressed in epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract[4,6]. CK20 is mainly expressed in the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract[4,6]. Mucin (MUC)2 is a specific marker of goblet cells in the gastrointestinal tract[4,6]. MUC1 is often expressed in epithelial tumors of the breast and female reproductive system[6]. Carbohydrate antigen (CA)125 is a membrane surface glycoprotein that is associated with ovarian cancer cells, which is expressed in the epithelium in most cases of ovarian cancer[6]. In female patients, different levels of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression are present in most primary ovarian epithelial tumors.

We reviewed 35 cases of PMP diagnosed at out hospital since the establishment of our hospital, and collected the clinical and pathological data of all the female patients. We carried out immunohistochemical studies to explore the causes and pathological origin of PMP in women, and to provide guidance for clinical diagnosis and treatment of PMP. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large sample study on the origin of PMP in Chinese women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical data

Our hospital treated 83 patients with PMP from 1962 to January 2010, including 38 women (45.8%) and 45 men (54.2%). Three of the 38 women with PMP did not undergo tumor resection or cytoreductive surgery, and underwent pathological examination only via puncture or biopsy, and were therefore, excluded from analysis. The clinical data for the remaining 35 female patients were reviewed, including age of onset, main symptoms and physical signs, imaging findings, intraoperative findings, surgical approach, pathological diagnosis, postoperative adjuvant therapy, recurrence, number of surgical procedures, and survival. The survival rate of patients was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Methods

Pathological sections were obtained from all patients to the best of our ability, and all pathological sections obtained were reviewed. For each patient, tissue blocks of lesions of the peritoneum, appendix, and ovary were selected for immunohistochemical staining. Three-micrometer sections of the paraffin-embedded tissue were deparaffinized, rehydrated in a graded series of alcohol and microwave-treated for 10 min in a citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide. The tissues were processed in an automatic immunohistochemical staining machine using the standard protocols (Lab Vision Autostainer; Lab Vision Co., Fremont, CA, USA) with DAKO Real™ EnVision™ Detection System (K5007, DAKO). We used the the following primary antibodies: CK7 (clone OV.TL-12/30, Dako; dilution 1:15 000), CK20 (clone Ks20.8, Dako; dilution 1:2000), MUC-1 (clone Ma 695, Novocastra; dilution 1:200) , MUC-2 (clone ccp58, Novocastra; dilution 1:100), CA125 (clone OC125, Dako; dilution 1:500), ER (clone 6F11, Novocastra; dilution 1:100), and PR (clone 16, Novocastra; dilution 1:200). All antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were visualized with 3-3′-diaminobenzidine and tissues were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. We used colon mucinous carcinoma tissue as a positive control for MUC2 and CK20, ovarian mucinous carcinoma tissue as positive control for MUC1, CA125 and CK7, and endometrial carcinoma tissue as a positive control for ER and PR. The same tissues without labeling by primary antibody were used as negative controls. Reactions were interpreted as positive, based on the presence of cytoplasmic staining for MUC2, CK7 and CK20 or cytoplasmic and membranous staining for MUC1 and CA125. For descriptive purposes, the staining was scored semi-quantitatively based on the percentage of positive cells: 1, negative; 2, < 10%; 3, 10-50%; and 4, > 50%. For comparative purposes, scores of 2-4 were considered to be positive.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

The 35 female patients were 24-76 years of age, with a mean age of 52.5 years. Most patients complained of abdominal distension and abdominal pain, and physical examination showed abdominal distension with ascites.

During surgery, a large volume of jelly-like mucous substances was seen in the abdomen. Multiple mucous lesions could be observed on the surface of the peritoneum and visceral organs. Thirty-one patients (88.6%) underwent appendectomy. A space-occupying lesion of the gallbladder was seen in one patient, whose appendix was not resected because intraoperative exploration of the appendix did not show any obvious abnormalities. The remaining three patients did not have a history of appendectomy, and the appendix was not explored during surgery.

Twenty-seven patients underwent ovarian resection, and mucinous ovarian tumors were observed in 24. In the remaining eight patients, no obvious abnormalities of the ovaries were observed during surgery, and the ovaries were not resected.

Lesions of the appendix and ovary were present in 20 patients (57.1%); 16 of whom underwent initial surgery for appendiceal lesions and four for ovarian lesions. None of these four patients underwent appendectomy, and the appendix was not explored during surgery. However, mucinous tumors recurred 1, 11, 32 and 85 mo after initial surgery, respectively, and appendiceal mucinous tumors were found in them. The other four patients with ovarian mucinous tumors did not undergo appendectomy, and the appendix was not explored during surgery in three patients, and a space-occupying lesion of the gallbladder was present in the remaining patient. The ovary was negative for tumor in 10 patients with appendiceal mucinous tumors.

Twenty-five patients (71.43%) underwent at least two surgical procedures, and all 35 patients received varying degrees of abdominal and systemic chemotherapy after surgery. Eleven patients died during follow-up (survival was 3-312 mo); five patients were lost to follow-up after 2-12 mo; and 19 patients survived with tumors (3-129 mo).

Pathological characteristics

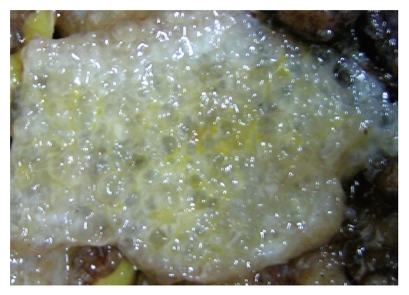

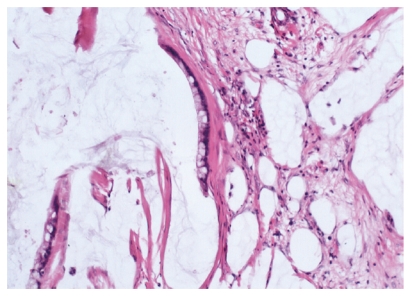

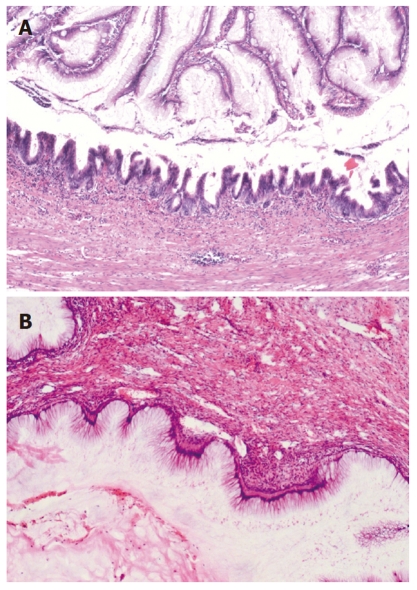

In all the patients, the intra-abdominal masses consisted of multiple nodules or grape-like masses; most of which had a smooth and shiny surface. Upon sectioning, the nodules were full of a jelly-like mucous substance (Figure 1). Microscopically, some mucous glandular structures were floating in a large number of mucous lakes, whose epithelium showed varying degrees of differentiation; mostly highly differentiated (Figure 2). Part of the epithelium was poorly differentiated. Mucinous tumors or tumor-like lesions were observed in 28 of 31 patients who underwent appendectomy (Figure 3A). Among the three patients who underwent surgery at other hospitals, the surgical pathology result was a chronic inflammatory mass of the appendix in one patient, no significant changes of the appendix in one patient, and unclear in the remaining patient. Ovarian mucinous tumors were found in 24 of the 27 patients who underwent resection of the ovary (Figure 3B). The tumors were bilateral in 13 cases, on the right side in nine, and on the left side in two (Table 1). The morphological changes in lesions of the appendix and ovary were similar to those of the peritoneal lesions.

Figure 1.

Upon sectioning, the peritoneal lesions were full of a jelly-like mucous substance.

Figure 2.

Microscopically, some mucous glandular structures were floating in a large number of mucous lakes (HE stain, × 200).

Figure 3.

Mucinous tumors were observed in the appendix (A) (HE stain, ×100) and ovary (B) (HE stain, × 100).

Table 1.

Pathological findings in 35 women with pseudomyxoma peritonei

| Ovary (n) | Other organs | Total (n) | ||||||

| Bilateral | Right-side | Left-side | NSC | UR | ||||

| Appendix (n) | Mucocele | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | 1 |

| MA | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 | No | 12 | |

| MAC | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | No | 15 | |

| Appendicitis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | 1 | |

| UP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | 1 | |

| NSC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | No | 1 | |

| UR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Gallbladder | 1 | |

| UDS | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | 3 | |

| Total (n) | 13 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 35 | ||

MA: Mucinous adenoma; MAC: Mucinous adenocarcinoma; UP: Unknown pathology; NSC: No significant changes; UR: Unresected; UDS: Unexplored during surgery.

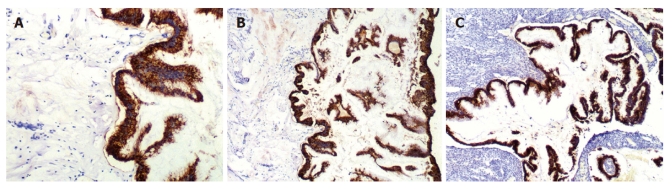

Immunohistochemistry results

CK20 and MUC-2 were positive in 33 of the 35 patients with peritoneal lesions (94.3%) (Figure 4A), but CK7, MUC-1 and CA125 were negative. The staining results of the appendix and/or ovaries (Figure 4B and C) were consistent with those of peritoneal lesions. In one patient, peritoneal tumors expressed CK20, CK7 and MUC-2, but not MUC-1 and CA125. That patient underwent appendectomy at another hospital, and no specimen was examined. No ovarian tumors were seen during surgery; consequently, the ovaries were not resected. The peritoneal and ovarian lesions were negative for CK20, MUC-2, CK7, MUC-1 and CA125 in one patient with a space-occupying lesion of the gallbladder. Additionally, ER and PR status was examined in the peritoneal, appendiceal, and ovarian lesions of the 24 patients with ovarian mucinous lesions, and the results were negative.

Figure 4.

Mucin-2 was positive in peritoneal (A) (× 200), appendiceal (B) (× 100) and ovarian (C) (× 100) lesions.

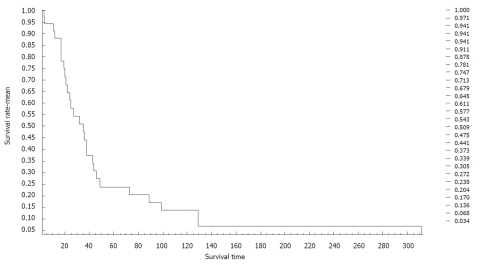

Survival

The survival of patients ranged between 2 and 312 mo. The average survival of patients was 47 mo, as calculated using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. The 3-, 5- and 10-year survival was 54.3%, 23.8% and 13.6%, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Survival of 35 women with pseudomyxoma peritonei.

DISCUSSION

PMP is a rare disease with a large volume of extensively implanted gelatinous mucous substance on the surface of the peritoneum or omentum majus[1,2]. The jelly-like substance is called pseudo-mucin, whose chemical properties are different from those of the mucous proteins. PMP was first discovered by Werth[1] in 1884, and its incidence is approximately 2/10 000 in all the patients who are undergoing laparotomy. This disease, with a mean age of 60 years (range: 30-88 years) and a male:female ratio 1:3.4, is characterized by unrelenting pain of gradual onset, abdominal distension, and mucous ascites in literatures. Ultimately, the tumor may occupy the majority of the abdominal cavity and “jelly belly” syndrome may occur. Definitive clinical diagnosis is very difficult to make, and almost all cases are diagnosed with assistance of laparotomy. Detection of jelly-like ascites through abdominal puncture has high diagnostic value for this disease. Our patients with PMP were 24-76 years of age, (mean age, 52.5 years), and the female:male ratio was 1:1.2.

The causes of PMP have remained controversial for many years. It has been reported that the primary tumor of PMP is present in many organs, of which the most common are the appendix and ovaries, followed by the Fallopian tube, pancreas, and intestine. The primary foci are hard to detect in some cases[2,3]. Most patients with PMP either suffer from appendiceal mucinous diseases (including cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma) or have a history of recent appendectomy[4-10]. In women, PMP may be accompanied by ovarian mucinous tumors, which often occur bilaterally. If the tumor occurs unilaterally, it more often affects the right ovary[9,10]. Clinically, about a third to a half of women with PMP have concurrent ovarian and appendiceal mucinous tumors.

Our hospital has treated 83 cases of PMP (45 men and 38 women) since the establishment of our hospital. The number of male patients was greater than female patients, which is different from that reported in the literature. Thirty-one of the 35 female patients in our study underwent appendectomy, and appendiceal mucinous tumors were seen in 28 of these. Three patients underwent surgery at other hospitals, and the pathological results of two were obtained. The pathological results of the remaining patient were unknown. For the two patients with pathological results, the pathological diagnosis was chronic inflammatory mass of the appendix in one patient, and no significant change in the appendix in the other. The remaining four patients did not have a history of appendectomy, and in three of them, the appendix was not explored during cytoreductive surgery for peritoneal tumor.

Twenty-four of the 35 patients had ovarian mucinous lesions, which were bilateral in 13 cases, on the right side in nine, and on the left side in two. Concurrent appendiceal and ovarian lesions occurred in 20 cases. It is controversial whether the ovarian lesions in these patients were primary or secondary to the appendiceal lesions.

In recent years, the techniques of immunohistochemistry and molecular biology have become more sophisticated, and have greatly enhanced our ability to identify the origin of this disease. In 1991, Young et al[5] analyzed 22 cases of ovarian mucinous tumors and PMP-induced appendiceal mucinous tumors. Their results showed that PMP and ovarian lesions both originated from the appendix. Subsequently, Ferreira[6] and Ronnett[7] have made the same observation. Using immunohistochemical methods, Dong et al[10] in China have analyzed CK7, CK20 and CA125 expression in peritoneal, ovarian and appendiceal tumors in women with PMP. These investigators drew the same conclusion. Szych et al[8] have analyzed the k-ras mutations and chromosome 18q, 17p, 5q and 6q alleles in patients with PMP. Their results support the conclusion that the ovarian lesions originate from the appendix in patients with PMP.

It has been reported in the literature that CK7 is a specific marker of primary ovarian epithelial tumors, which is rarely expressed in gastrointestinal epithelial cells[4,6]; however, our experience has shown that CK7 is not specific enough, and sometimes CK7 is positive in typical gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma. CK20 is mainly expressed in the epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract[4,6], but it can also be positive in intestinal-type ovarian mucinous tumors. MUC2 is a highly specific marker of intestinal goblet cells[4,6]. MUC1 is often expressed in epithelial tumors of the breast and female reproductive systems[6], but it is negative in epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract. CA125 is a surface membrane glycoprotein that is associated with ovarian cancer cells, which is positive in epithelial cells of most ovarian cancers[6]. In women, different levels of ER and PR expression are present in most of the primary ovarian epithelial tumors. Application of the aforementioned antibodies in the detection of tissue antigens is helpful in differentiating whether the tumor originates in the appendix or the ovaries.

Thirty-three of the 35 patients in our study had CK20- and MUC-2-positive peritoneal lesions, but CK7, MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR were negative. The expression pattern of the appendix and the ovary was similar to that of the peritoneal lesions. In one of the remaining two cases, CK20, CK7 and MUC-2 were positive, and MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR were negative. The ovaries were not resected because there were no abnormal intraoperative findings. This patient’s appendix was removed at another hospital, and no specimen was examined. In the other case, the appendix appeared to be normal during surgery and was not resected. Peritoneal and ovarian lesions were negative for CK20, MUC-2, CK7, MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR. The above results suggest that PMP and ovarian lesions were implanted and metastatic appendiceal tumors in 34 of the 35 cases.

It has been reported in the literature that the appendix can be normal in patients with PMP and ovarian mucinous tumors[11]. Lee et al[11] have studied 196 patients with borderline ovarian mucinous tumors; of whom, only 11 had PMP. These investigators stated that the apparent absence of appendiceal lesions could have been explained by a variety of circumstances, but that the appendix was not truly normal. First, the appendix may have been left unresected because the surgeon might have observed a normal-appearing appendix during surgery. Second, even if the appendix was resected, the sample collection might not have been sufficient and complete. Finally, even if a sufficient sample was collected, tiny foci of ruptured wall might have been missed due to failure to cut serial sections. In cases with apparent absence of appendiceal lesions, we believe that lesions may have been missed.

In our study, concurrent appendiceal and ovarian lesions occurred in 20 patients, of which, 16 underwent initial surgery for appendiceal lesions, and four for ovarian tumors. Abdominal recurrence occurred at 1-85 mo after surgery, and lesions of appendiceal mucinous tumors were found in all four patients. For one patient who underwent surgery that involved the right ovary, the surgeon explored the appendix during surgery, but the appendix was not resected because no obvious abnormalities were observed by the naked eye. Mucinous tumors were found throughout the abdominal cavity in that patient at 39 mo after surgery, and the resected appendix was confirmed to contain mucinous cystadenoma.

PMP caused by pancreatic mucinous tumor occasionally has been reported in the literature[15]. In our study, bilateral ovarian mucinous tumors were seen in one patient, accompanied by a space-occupying lesion of the gallbladder. The gallbladder was not resected due to the difficulty of the surgery. Immunohistochemical studies of the peritoneal and ovarian lesions showed that CK20, MUC-2, CK7, MUC-1, CA125, ER and PR were negative, which suggested that the ovarian tumor might be metastatic. In the literature, mucinous tumors of the gallbladder have not been reported to cause PMP, and this needs further study.

Treatment and prognosis of PMP

Treatment for PMP is complete resection of the tumors, supplemented by intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy. The disease often relapses, and recurrence occurs in 60%-76% of patients after surgery. Multiple surgical resections are often required, and sometimes > 20 operations are performed. Extent and invasiveness of PMP are the important causes of post-surgical recurrence. Although this disease may progress slowly, it is often fatal. The reported median survival was 5.9 years, and the 3-, 5- and 10-year survival was 81.1-83%, 50.0-81%, and 18.2-32%, respectively. Common causes of death are systemic infection secondary to wound infection, bowel obstruction, hernia, and pleural pseudomyxoma caused by tumor passing through the diaphragm. Twenty-five of the 35 patients in our study underwent two or more operations, and 11 patients died. The 5- and 10-year survival was 23.8% and 13.6%, respectively, which was lower than the survival reported in the literature. Therefore, we suggest close follow-up of patients with a diagnosis of PMP; especially those patients whose appendix has not been resected or explored during the initial surgery.

In summary, we believe that PMP often originates in the appendix, and that mucinous ovarian lesions are implanted or metastatic appendiceal tumors. Therefore, appendectomy should be performed routinely for patients in whom PMP is considered during laparotomy. The pathologist should carefully examine the gross specimen of the appendix, and collect as many tissue blocks as possible. Serial sections should be made for suspicious tissue blocks in order to search for small lesions. Additionally, because the incidence of ovarian involvement with implanted tumor is high in women with PMP, adnexa should be explored bilaterally during surgery; especially the right-side adnexa. Patients with PMP should be followed up closely; especially those whose appendix has not been resected or explored during initial surgery.

COMMENTS

Background

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare disease that is characterized by dissemination of voluminous jelly-like mucus on the peritoneal surface. Its etiology and pathological origin are not yet fully understood. It has been reported that PMP often originates from the appendix; however, a third to a half of PMP cases are accompanied by ovarian mucinous tumors in women.

Research frontiers

It has been controversial over the years whether the ovarian lesions in patients with PMP are primary or metastatic or implanted from the appendix. Most studies have indicated that PMP associated with ruptured mucinous lesions originates from the appendix. However, some authors consider that PMP originates from the ovaries. In this study, the authors demonstrated that most PMP in Chinese women originated from the appendix, and the ovarian tumors were implanted but not primary.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Recent reports have highlighted the origin of PMP in women. Unfortunately, few reports have observed the origin of PMP in Chinese women, and most of them were case reports or small studies. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first large sample study on the origin of PMP in Chinese women.

Applications

By understanding the appendiceal origin of PMP in women, appendectomy should be performed routinely for patients in whom PMP is considered during laparotomy. The pathologist should carefully examine the gross specimen of the appendix, and collect as many tissue blocks as possible. Serial sections should be made for suspicious tissue blocks in order to search for small lesions. Additionally, because the incidence of ovarian involvement with implanted tumor is high in women with PMP, the adnexae should be explored bilaterally during surgery, especially the right-side adnexa.

Terminology

PMP is a disease with a large volume of extensively implanted gelatinous mucous substance on the surface of the peritoneum. The term comes from the jelly-like substance, whose chemical properties are different from those of the mucous proteins, and called pseudo-mucin.

Peer review

This study considers the investigation of the histological origin of PMP in Chinese women, using immunohistochemical methods for detection of several mucin and tumor markers. The authors found that most PMP originated from the appendix, and among women, the PMP was predominately originated from implanted ovarian tumors. The study was set up correctly. The aim of the study was fulfilled. The figures give a good overview of the results. The methods used and the results are not described sufficiently well.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Tamara Vorobjova, Senior Researcher in Immunology, Department of Immunology, Institute of General and Molecular Pathology, University of Tartu, Ravila, 19, Tartu, 51014 Estonia, Tamara

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Werth R. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Arch Gynakol. 1884;24:100. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Ruth S, Acherman YI, van de Vijver MJ, Hart AA, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a review of 62 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:682–688. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran BJ, Cecil TD. The etiology, clinical presentation, and management of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:585–603. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(03)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin JH, Bae JH, Lee A, Jung CK, Yim HW, Park JS, Lee KY. CK7, CK20, CDX2 and MUC2 Immunohistochemical staining used to distinguish metastatic colorectal carcinoma involving ovary from primary ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:208–213. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young RH, Gilks CB, Scully RE. Mucinous tumors of the appendix associated with mucinous tumors of the ovary and pseudomyxoma peritonei. A clinicopathological analysis of 22 cases supporting an origin in the appendix. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:415–429. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira CR, Carvalho JP, Soares FA, Siqueira SA, Carvalho FM. Mucinous ovarian tumors associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei of adenomucinosis type: immunohistochemical evidence that they are secondary tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronnett BM, Shmookler BM, Diener-West M, Sugarbaker PH, Kurman RJ. Immunohistochemical evidence supporting the appendiceal origin of pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997;16:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szych C, Staebler A, Connolly DC, Wu R, Cho KR, Ronnett BM. Molecular genetic evidence supporting the clonality and appendiceal origin of Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1849–1855. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65442-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CY, Gu MJ, Wang SX, Ma D. Analysis of the clinical pathologic characteristic and prognosis with pseudomyxoma peritone. Prog Obstet Gynecol. 2002;11(4):268–270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Y, Li T, Zou W, Liang Y. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: report of 11 cases with a literature review. Zhonghua Binglixue Zazhi. 2002;31:522–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KR, Scully RE. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 196 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas, including an evaluation of 11 cases with ‘pseudomyxoma peritonei’. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1447–1464. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronnett BM, Seidman JD. Mucinous tumors arising in ovarian mature cystic teratomas: relationship to the clinical syndrome of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:650–657. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200305000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Yoshida S, Nishitani H, Uehara H. Localized pseudomyxoma peritonei in the female pelvis simulating ovarian carcinomatous peritonitis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:622–625. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200307000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JK, Song SH, Kim I, Lee KH, Kim BG, Kim JW, Kim YT, Park SY, Cha MS, Kang SB. Retrospective multicenter study of a clinicopathologic analysis of pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with ovarian tumors (KGOG 3005) Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:916–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imaoka H, Yamao K, Salem AA, Mizuno N, Takahashi K, Sawaki A, Isaka T, Okamoto Y, Yanagisawa A, Shimizu Y. Pseudomyxoma peritonei caused by acute pancreatitis in intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2006;32:223–224. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000194611.62723.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]