Abstract

The composition and dynamics of membrane protein complexes were studied in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 by two-dimensional blue native/SDS-PAGE followed by matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry. Approximately 20 distinct membrane protein complexes could be resolved from photoautotrophically grown wild-type cells. Besides the protein complexes involved in linear photosynthetic electron flow and ATP synthesis (photosystem [PS] I, PSII, cytochrome b6f, and ATP synthase), four distinct complexes containing type I NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH-1) subunits were identified, as well as several novel, still uncharacterized protein complexes. The dynamics of the protein complexes was studied by culturing the wild type and several mutant strains under various growth modes (photoautotrophic, mixotrophic, or photoheterotrophic) or in the presence of different concentrations of CO2, iron, or salt. The most distinct modulation observed in PSs occurred in iron-depleted conditions, which induced an accumulation of CP43′ protein associated with PSI trimers. The NDH-1 complexes, on the other hand, responded readily to changes in the CO2 concentration and the growth mode of the cells and represented an extremely dynamic group of membrane protein complexes. Our results give the first direct evidence, to our knowledge, that the NdhF3, NdhD3, and CupA proteins assemble together to form a small low CO2-induced protein complex and further demonstrate the presence of a fourth subunit, Sll1735, in this complex. The two bigger NDH-1 complexes contained a different set of NDH-1 polypeptides and are likely to function in respiratory and cyclic electron transfer. Pulse labeling experiments demonstrated the requirement of PSII activity for de novo synthesis of the NDH-1 complexes.

Photosynthetic organisms experience continuous fluctuation in their growth environment, including changes in light conditions, temperature, and nutrient availability. Cyanobacteria, the probable progenitors of chloroplasts, possess a remarkable capacity to adapt to a wide range of environmental conditions. Cyanobacteria are primarily photoautotrophic, but some strains, such as Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, can also grow mixotrophically or photoheterotrophically in the presence of external Glc. This, together with their flexibility to genetic manipulation and simple nutrient requirements for growth, has rendered cyanobacteria into a favored model in deciphering the structure-function relationships and acclimation strategies of the photosynthetic machinery.

Energy-transducing thylakoid membranes are the targets for modification by a number of environmental variables. Light, the most important environmental factor for photosynthesis, induces a well-defined acclimation response, including changes in the amount and ratio of the two PSs (Fujita, 1997; Hihara, 1999) and in the abundance and composition of the light-harvesting phycobilisome antenna (Grossman et al., 1993, 2001). Similar responses in the thylakoid membrane components also can be observed upon changes in the nutrient status, such as availability of iron (Straus, 1994; Sandström et al., 2002). Generally, iron deficiency induces a down-regulation of the iron-containing thylakoid components and, when possible, their replacement with noniron counterparts. A well-known response to iron deficiency is the derepression of the dicistronic isiAB operon (Vinnemeier et al., 1998), encoding a chlorophyll a (Chl a)-binding protein CP43′ (IsiA) and flavodoxin, respectively (Laudenbach and Straus, 1988; Laudenbach et al., 1988). Recently, CP43′ was demonstrated to form a Chl a-containing auxiliary antenna ring around PSI trimers in iron-deficient cells (Bibby et al., 2001; Boekema et al., 2001).

Increase in salinity of the growth medium likewise was reported to induce the expression of the isiAB operon (Vinnemeier et al., 1998; Vinnemeier and Hagemann, 1999) and accumulation of flavodoxin in salt-stressed cells (Fulda and Hagemann, 1995). This was suggested to contribute to enhanced cyclic electron transport around PSI upon salt stress (Hagemann et al., 1999). Conversely, salt stress appears to repress the genes encoding PSI components and subunits of the phycobilisomes (Kanesaki et al., 2002).

Limitation of inorganic carbon (Ci) in aquatic environments also poses a problem for photosynthesis. As a consequence, cyanobacteria have developed an extremely efficient carbon-concentrating mechanism, which operates to rise the CO2 concentration up to 1,000-fold around their relatively inefficient Rubisco enzyme (Badger and Price, 2003). Reverse genetics experiments have revealed that the uptake of Ci, either in the form of HCO3- or CO2, is accomplished by bicarbonate transporters (Omata et al., 1999; Shibata et al., 2002a) and CO2 uptake systems associated with the function of specialized type I NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH-1) complexes (Ogawa, 1991a, 1991b; Badger and Price, 2003) in the thylakoid membrane (Ohkawa et al., 2001). Besides CO2 uptake, NDH-1 complexes play a role in the cyclic electron transfer around PSI (Mi et al., 1994, 1995) and in the respiratory electron transfer (Mi et al., 1992; Schmetterer, 1994). Although the analysis of various ndh gene inactivation mutants has suggested a diversity of functions for NDH-1 complexes, the structural basis and protein composition of various hypothetical NDH-1 complexes have remained elusive.

During the past few years, genome-wide microarray studies of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 have provided a vast amount of information on global modification of gene expression in response to environmental variables (Hihara et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001; Kanesaki et al., 2002; Hihara et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2003). The challenge of future studies is to find out how the changes in transcript levels are realized on the protein level. Here, we have taken a functional proteomics approach to analyze the dynamic changes occurring in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 membrane protein complexes when the cells are subjected to elevated CO2 concentration, iron depletion, or salt stress or when their growth mode changes from photoautotrophy to mixotrophy or photoheterotrophy.

RESULTS

Protein Complexes of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Membranes: Photoautotrophic Growth Conditions

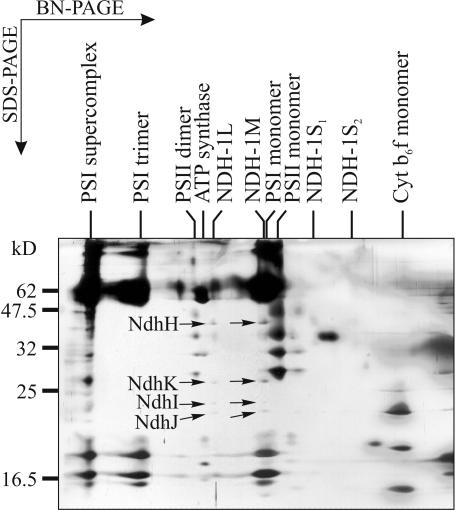

Membrane protein complexes from wild-type (WT) Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells grown photoautotrophically under air level of CO2 were first separated by blue native (BN)-PAGE. Approximately 20 distinct protein complexes could be observed in silver-stained BN gels (Fig. 1). To identify the protein complexes and to resolve their composition, the proteins from the BN gel lanes were separated in a second dimension by denaturing SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1), and the silver-stained protein spots were identified by mass spectrometric (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization time of flight [MALDI-TOF]) analysis or by immunoblotting (Fig. 2). Altogether, a total of 53 protein spots were identified as the products of 37 different Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 genes (Table I).

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE separation of the membrane protein complexes of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Membranes were isolated from WT cells grown photoautotrophically under air level of CO2. Upper, Silver-stained BN gel lane with electrophoretically separated membrane protein complexes, denoted above the gel lane. Below the lane, the molecular size markers (HMW Calibration Kit for Native Electrophoresis, Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) are shown in kilodaltons. The complexes were separated into their respective subunits by subjecting a BN gel lane to a denaturing SDS-PAGE (lower, silver stained SDS-PAGE). The numbered protein spots were excised from the silver-stained SDS-PAGE gels and identified with MALDI-TOF (see Table I).

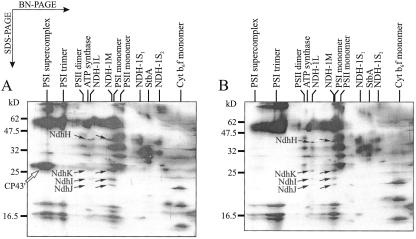

Figure 2.

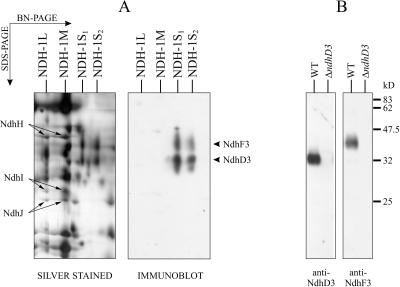

Identification of the NdhF3 and NdhD3 proteins by immunoblotting. A, After BN/SDS-PAGE, the proteins were silver stained (left) or electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and immunodecorated first with NdhF3 antibody and subsequently with NdhD3 antibody (right). Membranes containing 10 μg of Chl a were loaded in the BN-PAGE. A portion of the gels containing all NDH-1 complexes is shown. NdhH, NdhI, and NdhJ subunits are marked with arrows. The arrowheads on the right denote the positions of the NdhF3 and NdhD3 subunits in the NDH-1S complexes. B, Immunoblots demonstrating the specificity of the NdhD3 and NdhF3 antibodies. Membranes were isolated from WT and ΔndhD3 cells grown under air level of CO2. Membrane proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, electroblotted onto a membrane, and immunodecorated either with NdhD3 or NdhF3 antibody.

Table I.

Membrane proteins of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 identified by MALDI-TOF

The numbering corresponds to the BN/SDS-PAGE gel in Figure 1, except no. 32, which refers to Figure 6. ORF, Open reading frame in the Cyanobase. Experimental (Exper.) molecular masses were estimated by comparing the migration of the respective proteins with that of the Mr markers. Values of theoretical (Theor.) masses for unprocessed proteins are included. Results of searching in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database using Mascot are presented as: ratios of peptide masses that provided the identity to the total amount of peptides used in the search, percentages of coverage of full-length protein at 50 ppm, and score values according to Mascot.

| No.

|

ORF

|

Gene Product

|

Gene

|

Mass (kD)

|

Peptides

|

% Cover

|

Score

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exper. | Theor. | matched/total | ||||||

| 1 | slr1834 | PSI subunit la PsaA | psaA | 65 | 83.1 | 11/21 | 13 | 115 |

| slr1835 | PSI subunit lb PsaB | psaB | 65 | 81.4 | 8/21 | 10 | 90 | |

| 2 | slr0737 | PSI subunit ll PsaD | psaD | 18 | 15.7 | 9/13 | 52 | 161 |

| 3 | sll0819 | PSI subunit lll PsaF | psaF | 17 | 18.4 | 7/11 | 33 | 109 |

| 4 | slr1655 | PSI subunit Xl PsaL | psaL | 16 | 16.6 | 5/6 | 30 | 98 |

| 5 | slr0906 | PSII CP47 protein | psbB | 48 | 55.9 | 9/11 | 11 | 132 |

| 6 | sll0851 | PSII CP43 protein | psbC | 37 | 50.5 | 9/12 | 17 | 88 |

| 7 | sll0849 | PSII D2 protein | psbD | 31 | 39.6 | 10/12 | 19 | 135 |

| 8 | slr1311 | PSII D1 protein | psbA | 28 | 39.9 | 9/12 | 22 | 120 |

| 9 | sll1317 | Cytochrome f | petA | 22 | 35.3 | 12/15 | 39 | 204 |

| 10 | slr0342 | Cytochrome b6 | petB | 18 | 25.2 | 6/8 | 24 | 80 |

| 11 | slr0343 | Cytochrome b6f complex subunit IV | petD | 14 | 17.5 | 3/4 | 12 | 47 |

| 12 | sll1326 | ATP synthase α subunit | atpA | 59 | 53.9 | 12/31 | 27 | 129 |

| slr1329 | ATP synthase β subunit | atpB | 59 | 51.7 | 18/31 | 56 | 250 | |

| 13 | sll1327 | ATP synthase γ subunit | atpC | 31 | 34.6 | 15/18 | 28 | 178 |

| 14 | sll1324 | ATP synthase B subunit | atpF | 19 | 19.8 | 6/9 | 31 | 87 |

| 15 | sll1325 | ATP synthase δ subunit | atpD | 18 | 20.1 | 3/3 | 21 | 78 |

| 16 | slr1330 | ATP synthase ε subunit | atpE | 16 | 17.9 | 6/10 | 40 | 77 |

| 17 | sll1323 | ATP synthase B' subunit | atpG | 15 | 16.2 | 11/13 | 42 | 170 |

| 18 | slr0261 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 7, NdhH | ndhH | 43 | 45.8 | 20/22 | 26 | 159 |

| 19 | slr1280 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit NdhK | ndhK | 26 | 27.5 | 14/19 | 60 | 183 |

| 20 | sll0520 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit Ndhl | ndhI | 24 | 22.6 | 11/16 | 52 | 218 |

| 21 | slr1281 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit I, NdhJ | ndhJ | 23 | 20.7 | 6/9 | 18 | 106 |

| 22 | sll1732 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit, NdhF3 | ndhF3 | 40 | 66.6 | 3/6 | 4 | 36 |

| 23 | sll1733 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4, NdhD3 | ndhD3 | 32 | 54.4 | 4/6 | 6 | 65 |

| 24 | sll1734 | Protein involved in low CO2-inducible, high-affinity CO2 uptake, CupA | cupA | 45 | 50.2 | 21/29 | 50 | 253 |

| 25 | sll1735 | Protein homologous to secreted protein MPB70 | 17 | 14.2 | 5/6 | 53 | 103 | |

| 26 | slr1512 | Sodium-dependent bicarbonate transporter | sbtA | 30/27 | 39.7 | 13/16 | 17 | 145 |

| 27 | sll1577 | Phycocyanin beta subunit | cpcB | 18 | 18.3 | 8/22 | 60 | 126 |

| sll1578 | Phycocyanin alpha subunit | cpcA | 18 | 17.7 | 7/22 | 57 | 111 | |

| slr2067 | Allophycocyanin alpha subunit | apcA | 18 | 17.4 | 5/22 | 44 | 105 | |

| 28 | slr1128 | Stomatin-like protein | 32 | 35.7 | 13/20 | 42 | 193 | |

| 29 | slr0151 | Unknown protein | 38 | 35.0 | 14/20 | 51 | 166 | |

| 30 | sll1757 | Unknown protein | 28 | 31.8 | 6/8 | 20 | 156 | |

| 31 | slr0695 | Unknown protein | 18 | 19.1 | 5/7 | 38 | 94 | |

| 32a | sll0247 | Iron-stress induced Chl-binding protein CP43' | isiA | 28 | 37.3 | 12/16 | 24 | 88 |

| 33b | ssr3451 | Cytochrome b559 α subunit | psbE | 10 | 9.4 | 3/5 | 46 | 64 |

Complexes Related to Linear Photosynthetic Electron Flow and ATP Synthesis

PSI became distinguished as three major complexes, apparently representing a monomer, a trimer, and a high-molecular mass PSI supercomplex (Fig. 1). Moreover, a minor fraction of PSI resolved in BN gels apparently in a dimeric form. The reaction center subunits PsaA and PsaB, and PsaD, PsaF, and PsaL were identified by MALDI-TOF in the PSI complexes (Table I).

PSII complexes were resolved mainly as monomers but also as dimers or monomers lacking the CP43 subunit. The reaction center proteins D1 and D2, the Chl a-binding proteins CP47 and CP43, and the α-subunit of cytochrome b559 were identified in this study. Most small subunits of PSII, however, failed the identification by MALDI-TOF, whereas subunits of the oxygen-evolving complex apparently released from PSII upon membrane solubilization.

The cytochrome b6f (Cyt b6f) complex resolved mostly as a monomer, although a marginal amount of dimeric form was also observed in the gels. In both complexes cytochrome f, cytochrome b6, and subunit IV were identified.

The ATP synthase complex migrated in the BN gel slightly faster than the PSII dimer (Fig. 1). Subunits B and B′ of the membrane integral CF0 complex, and the extrinsic CF1 subunits α, β, δ, γ, and ε were identified by MALDI-TOF (Table I).

NDH-1 Complexes

Four complexes contained NDH-1 subunits. Based on their migration (and, correspondingly, the size), we denoted them as NDH-1L (large), NDH-1M (medium size), NDH-1S1 (small), and NDH-1S2 (Fig. 1). NDH-1L migrated in close proximity to ATP synthase, NDH-1M practically overlapped with the PSI monomer, NDH-1S1 migrated slightly faster than the CP43-less PSII monomer, and NDH-1S2 migrated between the NDH-1S1 and the Cyt b6f monomer. Both NDH-1L and NDH-1M contained the NdhH, NdhK, NdhI, and NdhJ subunits, which have been reported to belong to a NDH-1 subcomplex (Berger et al., 1993). The NDH-1S1 complex contained another set of four proteins, identified as NdhF3, NdhD3, CupA, and sll1735 gene product. High hydrophobicity of the NdhF3 and NdhD3 subunits resulted in formation of diffuse protein spots in SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 1) and low coverage data in MALDI analysis (Table I). However, antibodies raised against the NdhD3 and NdhF3 of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 explicitly identified these proteins in the NDH-1S1 and NDH-1S2 complexes and moreover, showed the absence of these subunits in the NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes (Fig. 2A). The specificity of the NdhD3 and NdhF3 antibodies is shown in Figure 2B. The NDH-1S2 complex is likely to represent either an assembly or degradation intermediate of NDH-1S1 because it contained only the NdhF3 and NdhD3 subunits.

Other Membrane Protein Complexes

A small protein complex migrating between the NDH-1S1 and NDH-1S2 complexes in the BN gel (Fig. 1) contained SbtA protein (Slr1512), which has been demonstrated as an essential component in a sodium-dependent bicarbonate transport in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Shibata et al., 2002a). Interestingly, both proteins (denoted as 26 in Fig. 1) belonging to this complex, albeit having different masses (30 and 27 kD), were identified as SbtA by MALDI-TOF (Table I).

In addition, we discovered several minor, previously unknown protein complexes. One of them, containing the slr0151 gene product, was observed in the close proximity to the PSII monomers (Fig. 1). Two other protein complexes, containing gene products of sll1757 and slr0695, respectively, migrated between the NDH-1S2 and Cyt b6f monomer. The function of these novel protein complexes remains to be investigated.

Effect of Growth Mode on the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Membrane Protein Complexes

Next, we tested the effect of the growth mode (photoauto-, mixo-, or photoheterotrophy) on the membrane proteome of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. To induce mixotrophic growth, the WT Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells were cultured in the light in the presence of 5 mm Glc. Analysis of the membrane protein pattern, however, did not reveal any significant changes of whether the WT cells were grown in the absence (Fig. 1) or presence (data not shown) of Glc. To induce photoheterotrophic growth conditions, the cell cultures were supplied with the PSII electron transfer inhibitor 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) in addition to Glc and light. These non-photosynthetic growth conditions induced notable changes in the pattern of membrane protein complexes (Fig. 3A). In particular, the NDH-1S1, NDH-1S2, and SbtA complexes were completely absent, and only traces of the NDH-1M complex were present. Conversely, two novel protein complexes in the range of 210 kD became strongly induced by these growth conditions and, therefore, were denoted as “Glc-induced” complexes. Mass spectroscopic analysis did not reveal the identity of the proteins belonging to these complexes, possibly because of strong hydrophobicity interfering the sample preparation.

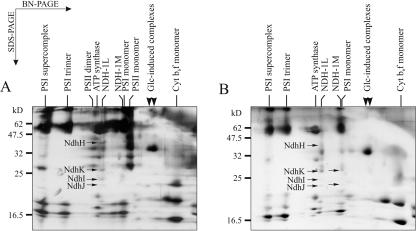

Figure 3.

Membrane proteome of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photoheterotrophic growth mode. Membranes were isolated from WT cells grown in the presence of 10 μm DCMU and 5 mm Glc (A) or from the PSII-less mutant strain LC grown in the presence of 5 mm Glc (B). Membranes corresponding to 10 μg of Chl a were subjected to BN/SDS-PAGE analysis as described in “Materials and Methods.” The NdhH, NdhK, NdhI, and NdhJ subunits in the NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes are marked with arrows. The arrowheads above the figures denote the Glc-induced complexes.

To exclude possible DCMU-induced side effects (Schmitz et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2000), we analyzed the membrane protein complexes of the photoheterotrophic mutant strain LC. This non-photosynthetic mutant is devoid of PSII complexes (Fig. 3B) and requires external Glc for growth (Mulo et al., 1997). Similar to the photoheterotrophically grown WT cells (Fig. 3A), the LC mutant lacked the NDH-1S1, NDH-1S2, and SbtA complexes but contained the two “Glc-induced” complexes in its membranes (Fig. 3B). Despite the absence of both NDH-1S complexes, low quantities of the NDH-1M and NDH-1L complexes were distinguished in the mutant membranes, with NDH-1L being the dominant one. Similar results were obtained with two other photoheterotrophic PSII-mutant strains PCD and CD (data not shown), which contain PSII complexes yet unable to support photoautotrophic growth (Mulo et al., 1997). Thus, the possibility that DCMU per se caused the changes in membrane protein complexes can be excluded.

As a control to the mutant LC, we tested the autotrophic mutant strain AR cultured in the presence or absence of Glc. This strain contains the same four antibiotic resistance genes as LC but no mutations in the PSII reaction center protein D1 (Mäenpää et al., 1993). When grown in the absence of Glc, the membrane protein profile of the strain AR strongly resembled that of the photoautotrophically grown WT strain (Fig. 4A versus Fig. 1). However, when the AR cells were grown in the presence of Glc, the membrane protein pattern showed a loss of the NDH-1S1, NDH-1S2, and SbtA complexes but contained the two “Glc-induced” complexes (Fig. 4B). In addition, the amount of the NDH-1M complex drastically decreased so that the NDH-1L complex became dominant. Thus, in regard to the NDH-1, SbtA, and “Glc-induced” complexes, the mixotrophically grown AR cells differed from the mixotrophically grown WT cells and resembled the photoheterotrophic PSII mutant strains (Fig. 3B) or WT strain grown in the photoheterotrophic mode (Fig. 3A).

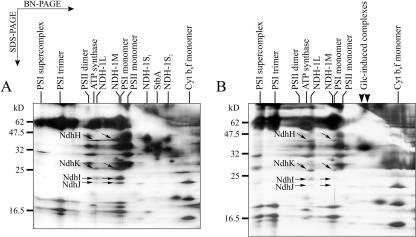

Figure 4.

BN/SDS-PAGE separation of membrane protein complexes of the mutant control strain AR. The AR cells were grown under standard growth conditions either photoautotrophically (A) or mixotrophically (B) in the presence of 5 mm Glc. Membranes containing 10 μg of Chl a were loaded in the BN-PAGE. The NdhH, NdhK, NdhI, and NdhJ subunits in the NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes are marked with arrows. The Glc-induced complexes are marked with arrowheads above B.

We also analyzed the protein complex profile of two other photoautotrophic mutant strains, an A2 mutant (Jansson et al., 1987) and a ΔpsbA1 mutant (for description of the mutants, see “Materials and Methods”), grown in the presence or absence of Glc. The membrane protein complexes of these mutant strains responded similarly to the AR strain to the availability of Glc as an energy source (data not shown). It should be noted that all mutant strains used in this study were grown in the presence of antibiotics.

Membrane Proteome during Growth under Elevated CO2

To study the effect of CO2 concentration on the accumulation of membrane protein complexes, we analyzed the membranes of WT cells grown under elevated CO2 concentration (1% [v/v] in air). The most pronounced changes induced by elevated CO2 were strong down-regulation of the NDH-1S1, NDH-1S2, and SbtA complexes and a marked reduction in the quantity of NDH-1M (Fig. 5). The content of the other membrane protein complexes showed no significant change in response to an elevated CO2 concentration (Fig. 5 versus Fig. 1).

Figure 5.

Effect of elevated CO2 concentration on the membrane protein complexes. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 membranes were isolated from WT cultures bubbled with 1% (v/v) CO2 in air. Membranes corresponding to 10 μg of Chl a were subjected to BN/SDS-PAGE analysis as described in “Materials and Methods.” Arrows mark the NdhH, NdhK, NdhI, and NdhJ subunits in the NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes.

Effect of Iron Deficiency or Salt Stress on the Membrane Proteome

The effects of iron starvation or increased salinity on the membrane protein complexes were studied with WT cells grown for 72 h in the absence of iron or in the presence of 0.4 m sodium chloride, respectively. Iron deficiency induced a pronounced accumulation of CP43′ protein (Fig. 6A). This protein was found solely in association with the PSI trimers, forming a big PSI-CP43′ supercomplex. This resulted in an increase in the amount of PSI-CP43′ supercomplexes relative to PSI trimers. Otherwise, the membrane proteome strongly resembled that of the WT cells grown in iron-sufficient conditions (Fig. 1).

Figure 6.

Effect of iron deficiency or salt stress on the membrane protein complexes. WT Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells were grown in the absence of iron (A) or in the presence of 0.4 m NaCl (B). Membranes corresponding to 10 μg of Chl a were subjected to BN/SDS-PAGE analysis. Black arrows mark the NdhH, NdhK, NdhI, and NdhJ subunits in the NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes. White arrow in (A) denotes the CP43′ protein (denoted as 32 in Table I).

The increase in the salinity of the growth medium, on the other hand, did not induce any noticeable changes in the membrane protein complexes (Fig. 6B), as compared with the cells cultured in the absence of added NaCl (Fig. 1).

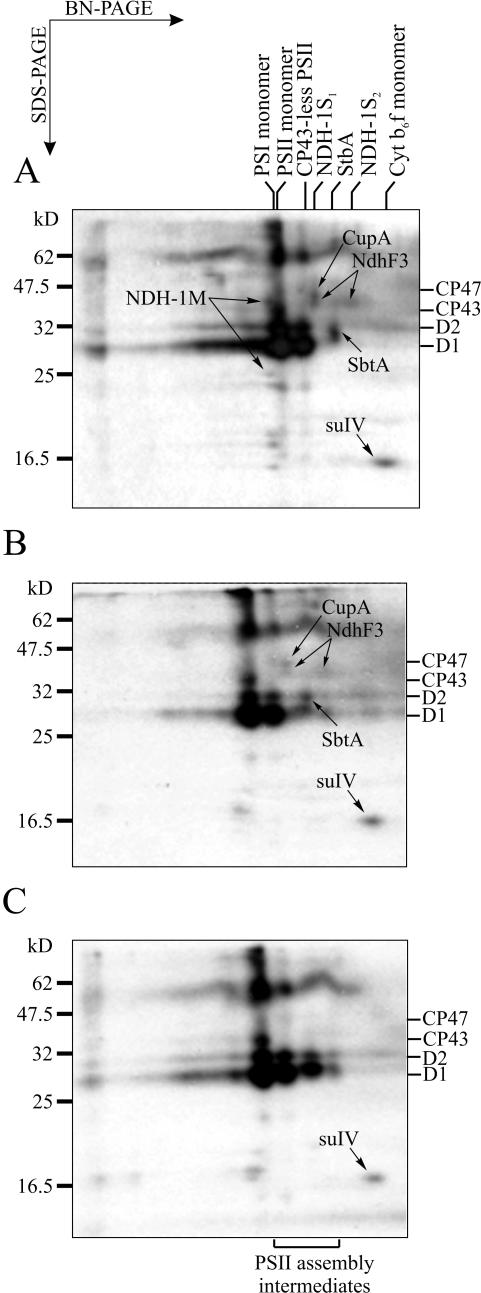

Synthesis of Membrane Protein Complexes

The expression patterns of membrane protein complexes described above represent a steady-state situation under each particular growth condition. To get insights into the synthesis and turnover of the membrane protein complexes, we performed [35S]Met labeling experiments with WT cells performing photoautotrophic, mixotrophic, or photoheterotrophic growth. The most distinct feature under all different growth conditions was the incorporation of radioactive Met into the PSII and its synthesis intermediates (Fig. 7). Labeling of subunit IV of the Cyt b6f complex was also observed under all growth conditions, suggesting a higher turnover rate for this protein as compared with the other Cyt b6f subunits. The NDH-1 subunits were synthesized in minor amounts. However, the synthesis of the NDH-1M and particularly the NDH-1S subunits NdhF3 and CupA was observed only during photoautotrophic and mixotrophic growth. Induction of photoheterotrophic growth by the addition of PSII inhibitor DCMU (15 min before labeling) completely abolished the incorporation of [35S]Met into these complexes. Labeling of the SbtA proteins followed closely that of the NDH-1 subunits under all growth conditions.

Figure 7.

Incorporation of radioactive Met into the membrane proteins in vivo. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 WT cells were labeled with [35S]Met under photoautotrophic (A), mixotrophic (B; light and 5 mm Glc), or photoheterotrophic (C; light and 15 μm DCMU) growth conditions. Membranes corresponding to 10 μg of Chl a were subjected to BN/SDS-PAGE analysis as described. The main labeled polypeptides, besides the PSII core proteins, are marked with arrows. The positions of PSII core subunits CP47, CP43, D2, and D1 are denoted on the right of each figure. SuIV, Subunit IV of Cyt b6f complex. The position of PSII assembly intermediates is denoted below C.

DISCUSSION

Cyanobacterial membranes are dynamic entities, changing their protein composition in response to a wide variety of environmental factors, including light quality and quantity (Fujita, 1997; Hihara, 1999), iron availability (Straus, 1994; Sandström et al., 2002), CO2 concentration (Murakami et al., 1997; Deng et al., 2003), and salinity (Murakami et al., 1997). These changes are necessary to balance the energy transduction processes and to minimize photooxidative damage, thus being crucial for the cyanobacterial growth in the ever-changing environment. Previous studies on acclimation of the thylakoid protein complexes have addressed mainly the dynamics of the two PSs. Compared with the vast amount of information available on the cyanobacterial photosynthetic complexes, far less is known about the composition, structure, and dynamics of other membrane-embedded protein complexes.

Diversity of the NDH-1 Complexes

The most distinctive novel feature of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 membranes observed in this study was the multiplicity of complexes containing NDH-1 subunits. The NDH-1 subunits are encoded by at least 10 single copy genes (ndhAIGE, ndhB, ndhCJK, ndhH, and ndhL) and two multigene families (ndhF family with three members and ndhD family with six members; Badger and Price, 2003). Altogether four distinct NDH-1 complexes, denoted here as NDH-1L, -M, -S1, and -S2, were resolved in BN-PAGE (Fig. 1).

The multisubunit NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes showed a similarity in their protein composition. Both complexes contained the NdhH, -K, -I, and -J subunits (Fig. 1; Table I). In addition, they contained several other, still unidentified proteins. It is conceivable that these proteins represent more hydrophobic NDH-1 subunits because they were not effectively digested by trypsin to provide representative sets of peak masses. These subunits must therefore be identified by other methods than MALDI-TOF.

Two smaller complexes, NDH-1S1 and NDH-1S2, contained a set of proteins different from that of NDH-1L or NDH-1M. NDH-1S1 consisted of four proteins, two of which comprised NDH-1S2. The first hints for the identity of these two common subunits came from MALDI-TOF analysis. In the spectrum of the protein with an apparent molecular mass of 32 kD, four peaks were observed that referred to NdhD3, and in the spectrum of the protein of 40 kD, three peaks were observed that referred to NdhF3. The reason for obtaining low-coverage data in the MALDI-TOF analysis is likely to be related to the high hydrophobicity of the NdhF3 and NdhD3 proteins, which apparently also induced an anomalous migration of these proteins in the SDS-PAGE. However, the protein specific antibodies confirmed the identity of the NdhF3 and NdhD3 proteins in the NDH-1S complexes (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that the NDH-1L and NDH-1M complexes lacked the NdhF3 and NdhD3 subunits, whereas the NDH-1S complexes appeared to lack the subunits belonging to NDH-1L and NDH-1M (Fig. 2).

Reverse genetics approaches have revealed that NdhF3, NdhD3, NdhF4, and NdhD4 subunits contribute mainly to the uptake of CO2 (Klughammer et al., 1999; Ohkawa et al., 2000a, 2000b; Shibata et al., 2001), whereas NdhF1, NdhD1, and NdhD2 are involved in respiration and cyclic electron transfer around PSI (Yu et al., 1993; Klughammer et al., 1999; Ohkawa et al., 2000a). Previous mutant studies by Ogawa and coworkers also have demonstrated a role for the NdhB, NdhK, and NdhL subunits in the uptake of CO2 and in the NDH-1-mediated electron transfer pathways (Ogawa, 1991a, 1991b, 1992; Mi et al., 1992, 1994; Ohkawa et al., 2000b). Based on these results, it was hypothesized that there may exist several functionally distinct NDH-1 complexes, all sharing a core encoded by the single-copy genes but differing in their NdhF and/or NdhD components. In variance with this hypothesis, our results suggest that the CO2 uptake complex formed by NdhF3 and NdhD3 is a separate complex from the other NDH-1 complexes containing single-copy NDH-1 subunits. It is evident, however, that the NDH-1S complexes are functionally dependent on NDH-1M (or NDH-1L), and at the moment, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the NDH-1S complexes may represent subcomplexes of the larger NDH-1 complexes.

In addition to NdhF3 and NdhD3, we identified the CupA protein (Sll1734, also known as ChpY) in the NDH-1S1 complex. The genes for NdhF3, NdhD3, and CupA are clustered in the genomes of several unicellular cyanobacteria (Klughammer et al., 1999; Ohkawa et al., 2000b; Maeda et al., 2002) and transcribed together into a tri-cistronic mRNA (Ohkawa et al., 2000b; McGinn et al., 2003). Similarly to NdhF3 and NdhD3, the CupA protein was suggested to play a role in high-affinity CO2 uptake because this process was impaired in CupA-deficient mutants (Klughammer et al., 1999; Shibata et al., 2001; Maeda et al., 2002). Our data here give the first direct evidence, to our knowledge, that these three proteins associate with each other to form a membrane-embedded protein complex.

Interestingly, the NDH-1S1 complex was found also to contain a fourth subunit, encoded by sll1735. The sll1735 gene is located immediately downstream of the ndhF3/ndhD3/cupA operon (Klughammer et al., 1999; Ohkawa et al., 2000b; Maeda et al., 2002), but it is apparently transcribed independently of the other NDH-1S1 subunits (Ohkawa et al., 2000b). Inactivation of the sll1735 gene had no significant effect on the growth or uptake of CO2 in cyanobacterial cells under low CO2 conditions (Klughammer et al., 1999; Ohkawa et al., 2000b). Our results show that the Sll1735 protein is an intrinsic component of the NDH-1S1 complex, although its specific role still remains to be elucidated.

We did not find the constitutively expressed, low-affinity CO2 uptake complex containing the NdhF4, NdhD4, and CupB proteins (Shibata et al., 2001; Maeda et al., 2002). It might be that this complex was expressed at a relatively low level and, therefore, was not seen in our gels.

Dynamics of the NDH-1 Complexes

The NDH-1 complexes, particularly NDH-1S1 and NDH-1S2, were the most dynamic group of membrane protein complexes. The two NDH-1S complexes were strongly expressed in cells cultured photoautotrophically under air levels of CO2, whereas an increase in CO2 concentration drastically reduced the expression of these protein complexes (Fig. 1 versus Fig. 5). This observation is in accordance with the studies showing that the NdhF3, NdhD3, and CupA subunits play a role in high-affinity CO2 uptake, induced during acclimation of cells to low CO2 conditions (Klughammer et al., 1999; Shibata et al., 2001; Maeda et al., 2002). Accumulation of the NDH-1S complexes under low CO2 conditions appears to be regulated at the level of transcription because the abundance of the ndhF3, ndhD3, and cupA transcripts was reported previously to become strongly up-regulated by Ci limitation (Figge et al., 2001; McGinn et al., 2003). Iron deficiency or salt stress, on the other hand, had no distinct effect on any of the NDH-1 complexes (Fig. 6).

Intriguingly, accumulation of the NDH-1S complexes was also affected by the growth mode of the cells. Pulse labeling experiments of photoautotrophically grown WT cells revealed ongoing synthesis of NDH-1S complexes (Fig. 7A), which resulted in high steady-state amounts of these complexes in the membrane (Fig. 1). Similar results were obtained using mixotrophically cultured WT cells (Fig. 7B), indicating that the cells relied on active CO2 uptake even in the presence of external organic carbon source. Analysis of metabolic fluxes using the carbon isotope labeling technique has demonstrated that during mixotrophic growth of WT Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, carbon is assimilated mainly via the Calvin cycle, whereas the catabolism of Glc has only a minor role in carbon metabolism (Yang et al., 2002). In contrast, no NDH-1S complexes were present in membranes of WT cells performing photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of DCMU (Fig. 3A). The [35S]Met labeling experiments revealed no synthesis of the NDH-1 complexes under these non-photosynthetic conditions (Fig. 7C). This suggests that photosynthetic activity, and the activity of PSII in particular, is required for NDH-1S accumulation. This is consistent with the inhibition of light-induced transcription of the ndhF3/ndhD3/cupA operon by DCMU (Figge et al., 2001). Moreover, at the functional level, DCMU was shown recently to specifically inhibit the uptake of CO2 by the high-affinity uptake system (Maeda et al., 2002; Shibata et al., 2002b), which is represented here by the NDH-1S1 complex.

Similar to photoheterotrophic WT cells, the nonphotosynthetic PSII mutant strains were devoid of NDH-1S complexes (Fig. 3B; data not shown). This confirms the importance of PSII function for NDH-1S accumulation and excludes the possibility that the lack of NDH-1S in photoheterotrophic WT cells was a nonspecific side effect caused by DCMU. Somewhat surprisingly, the down-regulation of NDH-1S content was also observed when the photosynthetic mutant cells AR, A2, and ΔpsbA1 were grown mixotrophically in the presence of Glc (Fig. 5; data not shown). Although the physiological process behind this phenomenon remains to be solved, it is highly likely that the mutant cells grown under energetically demanding antibiotic stress become more amenable to exploit external Glc as their energy source than the unstressed WT cells. This would reduce the need for CO2 fixation via the Calvin cycle and result in down-regulation of the CO2 uptake complex NDH-1S.

It is noteworthy that the accumulation of the NDH-1S and the NDH-1M complexes was closely paralleled under all growth conditions. This further supports the idea obtained by mutant analysis that these two complexes probably function in cooperation. The observed down-regulation of the NDH-1M content under elevated CO2 (Fig. 5) is consistent with the recent results of Deng et al. (2003) showing reduced amounts of the NdhH, NdhI, and NdhK subunits in cells grown under high CO2. The NDH-1L complexes, in contrast, appeared relatively unaffected by the different growth conditions. However, the mutant cells grown under antibiotic stress generally contained a higher amount of NDH-1L complexes than the WT cells (Figs. 3B and 4). Based on the differences in the accumulation patterns, it is tempting to speculate that the NDH-1M and NDH-1L complexes, despite having at least partly similar subunit composition, may play functionally different roles. The NDH-1M might operate together with NDH-1S to facilitate the uptake of CO2, whereas the NDH-1L might be specifically involved in respiratory electron transfer chain and become up-regulated under energetically demanding stress conditions. This notion is further supported by a nearly complete lack of NDH-1M and by a strong up-regulation of the NDH-1L complex in a PSI-less mutant strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (N.V. Battchikova, P. Zhang, and E.-M. Aro, unpublished data).

Dynamics of PSI and PSII Complexes

Previous studies of thylakoid adaptation mainly have addressed the dynamics of the two PSs and their light-harvesting antenna (Fujita, 1997; Hihara, 1999; Grossman et al., 2001). Although our experimental system was not quantitative enough to reveal modulations in the relative steady-state amounts of PSI and PSII under the different growth conditions, a very distinct accumulation of CP43′ protein (IsiA) associated with PSI supercomplexes was evident when Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells were grown in iron-depleted growth medium (Fig. 6A). Recently, the CP43′ protein was shown to form an additional Chl a-containing antenna around PSI trimers (Bibby et al., 2001; Boekema et al., 2001), increasing the absorption cross section of PSI up to 100% (Andrizhiyevskaya et al., 2002). This was suggested to compensate the decrease in the PSI and phycobilisome content because of limited iron supply for their synthesis (Bibby et al., 2001). However, we often observed trace amounts of CP43′ and PSI supercomplexes even in cells grown in the presence of iron. Accumulation of the CP43′ protein may represent a more general acclimation response because the transcription of the isiAB operon (encoding CP43′ and flavodoxin, respectively) was inferred recently to be induced also under oxidative stress conditions (Jeanjean et al., 2003).

Higher expression levels of the isiAB operon also have been observed in cells grown under salt stress (Vinnemeier et al., 1998; Vinnemeier and Hagemann, 1999). However, under our experimental conditions, the salt stress did not induce up-regulation in the amount of the CP43′ protein (Fig. 6B). In fact, the lack of any distinctive changes in the steady-state levels of photosynthetic proteins or protein complexes under salt stress conditions agrees with earlier studies demonstrating that plasma membrane, the outer membrane, and the cytosol are the main targets of salt stress via the accumulation of osmolytes and systems for active extrusion of sodium ions (for review, see Joset et al., 1996).

Despite the relatively static image of PS complexes obtained from the steady-state data, the pulse labeling experiments revealed active synthesis of these complexes in cells grown photoauto-, mixo-, or photoheterotrophically (Fig. 7). The most notable feature was the active synthesis of PSII, and particularly of the PSII reaction center protein D1, under all conditions tested. The D1 protein is prone to continuous light damage, degradation, and de novo synthesis to maintain the photosynthetic activity (Aro et al., 1993). This so-called PSII repair cycle was characterized by labeling of PSII core monomer intermediate complexes and, thus, was shown to be strongly operational independently of the growth mode of the cells.

Other Membrane Protein Complexes

A protein complex containing the SbtA protein(s) was among the most dynamic complexes in the cyanobacterial membranes. Inactivation of the sbtA gene severely depresses the Na+-dependent HCO3- uptake in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Shibata et al., 2002a). Thus, the SbtA protein complex seen in our gels most likely represents the low CO2-induced, Na+-dependent HCO3- transporter suggested by Shibata et al. (2002a). Expression of the SbtA protein complex closely followed the alterations in the expression of NDH-1S under all growth conditions, suggesting that these two Ci uptake mechanisms share a common regulatory pathway.

Expression of two novel protein complexes, denoted as the “Glc-induced” complexes, was strongly induced under photoheterotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 3) and in mixotrophic mutant cultures (Fig. 4B). Although the exact role of these protein complexes awaits the identification of their constituent subunits, their induction under conditions where the cells were likely to rely on external Glc for their growth strongly suggests that they are involved either in the uptake of Glc or in the oxidation of NADPH formed by Glc catabolism. The scarcity of these complexes in the mixotrophic WT cultures is in line with the observation that the Glc catabolism plays only a minor role in the mixotrophically grown WT cell cultures (Yang et al., 2002).

The rest of the membrane protein complexes showed no drastic modulation under the various growth conditions. However, we observed three novel protein complexes, including sll1757, slr0151, and slr0695 gene products, respectively. Although the physiological role of these proteins remains to be solved, we show here that these proteins are components of membrane-embedded complexes.

We conclude that the BN/SDS-PAGE is a powerful method for analysis of the composition and dynamics of membrane protein complexes of cyanobacterial cells. Of particular interest was the observation of four distinct NDH-1 complexes, whose accumulation was regulated by environmental cues. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the gene products of the ndhF3/ndhD3/cupA operon associate together as a protein complex and introduce a new subunit for this CO2 uptake complex. In addition to the already known cyanobacterial membrane components, several new protein complexes, formed by proteins with unknown functions, are reported. The function of these novel protein complexes remains to be elucidated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Growth Conditions

A Glc-tolerant strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Williams, 1988) was used as the WT. In addition, seven mutant strains were studied. In the mutant ΔndhD3, a kanamycin resistance cassette interrupts the ndhD3 gene (Ohkawa et al., 2000b). The other six mutant strains have mutations in the psbA genes, encoding PSII reaction center protein D1. The mutant strain ΔpsbA1 has a chloramphenicol resistance cassette replacing the silent psbA1 gene. In the mutant A2, the psbA1 and psbA3 genes are insertionally inactivated with kanamycin and chloramphenicol resistance genes, respectively, leaving the psbA2 as the only functional psbA gene (Jansson et al., 1987). Strain AR, a derivative of A2, has an additional Ω-fragment (streptomycin and spectinomycin resistance cassette) after the psbA2 gene (Mäenpää et al., 1993). The strains LC (ΔT227-Y246), CD (ΔG240-V249), and PCD (ΔR225-V249) are derivatives of AR, containing additional deletions in the psbA2 gene in a region corresponding to the D-E loop of the D1 protein (Mulo et al., 1997). The strains LC, CD, and PCD are obligate photoheterotrophs, whereas all the other strains are capable in photoautotrophic growth.

All strains were grown in 200-mL batch cultures of BG-11 medium (Stanier et al., 1971) buffered with 20 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5) at 32°C. The cultures were maintained under continuous light of 50 μmol photons m-2 s-1 under air level of CO2 unless otherwise indicated. The growth media for the mutant strains were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (Jansson et al., 1987; Mäenpää et al., 1993; Mulo et al., 1997) at concentrations of 2.5 μg mL-1 for chloramphenicol, 5 μg mL-1 for kanamycin and streptomycin, and 10 μg mL-1 for spectinomycin. The growth media for the photoheterotrophic mutants were supplied additionally with 5 mm Glc.

To induce mixotrophic or photoheterotrophic growth of WT or photoautotrophic mutant cultures (AR, A2, and ΔpsbA1), the cells were grown in the presence of 5 mm Glc or Glc together with 10 μm DCMU (Sigma, St. Louis), respectively. Measurements of oxygen evolution by a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech, Kings Lynn, UK) confirmed that the 10 μm concentration of DCMU prevented oxygen evolution in vivo. Iron stress was induced by replacing ferric ammonium citrate with ammonium citrate in the growth media. Salt stress was induced by growing the cells in the presence of 0.4 m NaCl. During all treatments, the cells were let to adapt to prevailing conditions for several generations before harvesting at the logarithmic growth phase (A750 0.6-0.8, measured with Spectronic Genesys 2 spectrophotometer, Spectronic Instruments, Inc., Rochester, NY).

Isolation of the Membrane Fraction

Membranes were isolated essentially as described by Gombos et al. (1994). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000g for 8 min at 4°C) and washed twice with washing buffer (50 mm HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.5] and 30 mm CaCl2). The cells were then broken in isolation buffer (50 mm HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.5], 30 mm CaCl2, 800 mm sorbitol, and 1 mm ε-amino-n-caproic acid) by vortexing them in the presence of glass beads (150-212 microns; Sigma) for 8 min at 4°C. Unbroken cells and glass beads were removed by centrifugation at 550g for 5 min. The membranes were pelleted from the supernatant by centrifugation at 17,000g for 20 min, resuspended in storage buffer (50 mm Tricine-NaOH [pH 7.5], 600 mm Suc, 30 mm CaCl2, and 1 m glycinebetaine), and stored at -70°C. All steps were performed in dim light at 4°C. Isolated membranes were highly enriched with thylakoids but apparently also contained fragments originating from plasma membrane.

Determination of Chl Concentration of Isolated Membranes

The Chl a content of the isolated membranes was determined according to Arnon (1949).

BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE

BN-PAGE was performed according to Kügler et al. (1997), with the modifications of Cline and Mori (2001). Cyanobacterial membranes were washed with washing buffer (330 mm sorbitol, 50 mm BisTris [pH 7.0], and 250 μg mL-1 Pefabloc [Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis]), collected by centrifugation (18,000g for 10 min), and resuspended in resuspension buffer (20% [w/v] glycerol, 25 mm BisTris [pH 7.0], 10 mm MgCl2, 0.1 units μL-1 RQ1 RNase-Free DNase [Promega, Southampton, UK], and 250 μg mL-1 Pefabloc) at Chl a concentration of 1 mg mL-1. An equal volume of resuspension buffer containing 4% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (Sigma) was added under continuous mixing, and the solubilization of membrane protein complexes was allowed to occur for 50 min on ice, followed by 10 min at room temperature. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 18,000g for 20 min. The supernatant was mixed with 0.1 volumes of Coomassie Blue solution (5% [w/v] Serva blue G, 100 mm BisTris [pH 7.0], 30% [w/v] Suc, 500 mm ε-amino-n-caproic acid, and 10 mm EDTA) and loaded onto 0.75-mm-thick 5% to 12.5% (w/v) acrylamide gradient gel (Hoefer Mighty Small mini-vertical unit, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala), containing 500 mm ε-amino-n-caproic acid. Electrophoresis was performed at 4°C by increasing voltage gradually from 50 up to 200 V during the 4.5-h run. For separation of proteins in the second dimension, the lanes of the BN gel were excised and incubated in SDS sample buffer containing 10% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and 6 m urea for 45 min at room temperature, followed by 15 min at 40°C. The lanes were then layered onto 1-mm-thick SDS-PAGE gels (Laemmli, 1970), with 14% (w/v) acrylamide and 6 m urea in the separating gel. The proteins were visualized by silver staining (Blum et al., 1987, except that the stop buffer was replaced by 0.4 m Tris and 2.5% [v/v] acetic acid), by autoradiography ([35S]Met labeled proteins), or by electroblotting the proteins onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon P, Millipore, Bedford, MA) and immunodetection by protein-specific antibodies using the CDP-Star Chemiluminescent Detection Kit (New England Biolabs Ltd., Hertfordshire, UK). The NdhD3 antibody was raised against the amino acids 185 to 196 and 346 to 359, and NdhF3 antibody was raised against the amino acids 28 to 41 and 439 to 453 of the respective proteins of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium).

Labeling of Membrane Proteins in Vivo

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 WT cells were grown photoautotrophically or mixotrophically under standard growth conditions until the logarithmic growth phase and adjusted to Chl a concentration of 10 μg mL-1. Thereafter, the cell suspensions were pulse labeled with 3 μCi mL-1 [35S]Met (>1,000 Ci mmol-1, Amersham Biosciences UK Ltd.) for 30 min under conditions supporting photoautotrophic, mixotrophic, or photoheterotrophic growth. The photoheterotrophic growth conditions were induced by supplying the photoautotrophically grown cell culture with 15 μm DCMU 15 min before labeling. Labeling was terminated by adding 1 mm nonradioactive Met and 0.5 mg mL-1 chloramphenicol, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C. Membranes were isolated and subjected to BN/SDS-PAGE as described. After BN/SDS-PAGE, the gels were dried, and the proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Identification of Proteins by MALDI-TOF

In-gel trypsin digestion and sample preparation for MALDI-TOF analysis was done manually according to Shevchenko et al. (1996). Samples were loaded onto the target plate by the dried droplet method using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as a matrix. MALDI-TOF analysis was performed in reflector mode on a Voyager-DE PRO mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Internal mass calibration of spectra was based on trypsin autodigestion products (842.5094 and 2,211.1046 m/z). Proteins were identified as the highest ranking result by searching in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database using Mascot (http://www.matrixscience.com). The search parameters allowed for carbamidomethylation of cystein, one miscleavage of trypsin, and 50 ppm mass accuracy. For positive identification, the score of the result of [- 10 × Log(P)] had to be over the significance threshold level (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Teruo Ogawa for the ΔndhD3 mutant, Dr. Bruce Diner for the ΔpsbA1 mutant, and Dr. Wim Vermaas for the PSI-less mutant. The mass spectrometer group in the Turku Centre for Biotechnology is thanked for advice in protein analysis.

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.032326.

References

- Andrizhiyevskaya EG, Schwabe TME, Germano M, D'Haene S, Kruip J, van Grondelle R, Dekker JP (2002) Spectroscopic properties of PSI-IsiA supercomplexes from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC 7942. Biochim Biophys Acta 1556: 265-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI (1949) Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts: polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol 24: 1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro E-M, Virgin I, Andersson B (1993) Photoinhibition of photosystem II: inactivation, protein damage and turnover. Biochim Biophys Acta 1143: 113-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD (2003) CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J Exp Bot 54: 609-622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S, Ellersiek U, Kinzelt D, Steinmüller K (1993) Immunopurification of a subcomplex of the NAD(P)H-plastoquinone-oxidoreductase from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. FEBS Lett 326: 246-250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby TS, Nield J, Barber J (2001) Iron deficiency induces the formation of an antenna ring around trimeric photosystem I in cyanobacteria. Nature 412: 743-745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum H, Beier H, Gross HJ (1987) Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 8: 93-99 [Google Scholar]

- Boekema EJ, Hifney A, Yakushevska AE, Piotrowski M, Keegstra W, Berry S, Michel K-P, Pistorius EK, Kruip J (2001) A giant chlorophyll-protein complex induced by iron deficiency in cyanobacteria. Nature 412: 745-748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline K, Mori H (2001) Thylakoid ΔpH-dependent precursor proteins bind to a cpTatC-Hcf106 complex before Tha4-dependent transport. J Cell Biol 154: 719-729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Ye J, Mi H (2003) Effects of low CO2 on NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, a mediator of cyclic electron transport around photosystem I in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Cell Physiol 44: 534-540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figge RM, Cassier-Chauvat C, Chauvat F, Cerff R (2001) Characterization and analysis of an NAD(P)H dehydrogenase transcriptional regulator critical for the survival of cyanobacteria facing inorganic carbon starvation and osmotic stress. Mol Microbiol 39: 455-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y (1997) A study on the dynamic features of photosystem stoichiometry: accomplishments and problems for future studies. Photosynth Res 53: 83-93 [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S, Hagemann M (1995) Salt treatment induces accumulation of flavodoxin in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. J Plant Physiol 146: 520-526 [Google Scholar]

- Gombos Z, Wada H, Murata N (1994) The recovery of photosynthesis from low-temperature photoinhibition is accelerated by the unsaturation of membrane lipids: a mechanism of chilling tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 8787-8791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AR, Bhaya D, He Q (2001) Tracking the light environment by cyanobacteria and the dynamic nature of light harvesting. J Biol Chem 276: 11449-11452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AR, Schaefer MR, Chiang GG, Collier JL (1993) The phycobilisome, a light-harvesting complex responsive to environmental conditions. Microbiol Rev 57: 725-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M, Jeanjean R, Fulda S, Havaux M, Joset F, Erdmann N (1999) Flavodoxin accumulation contributes to enhanced cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in salt-stressed cells of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Physiol Plant 105: 670-678 [Google Scholar]

- Hihara Y (1999) The molecular mechanism for acclimation to high light in cyanobacteria. Curr Top Plant Biol 1: 37-50 [Google Scholar]

- Hihara Y, Kamei A, Kanehisa M, Kaplan A, Ikeuchi M (2001) DNA microarray analysis of cyanobacterial gene expression during acclimation to high light. Plant Cell 13: 793-806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihara Y, Sonoike K, Kanehisa M, Ikeuchi M (2003) DNA microarray analysis of redox-responsive genes in the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 185: 1719-1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson C, Debus RJ, Osiewacz HD, Gurevitz M, McIntosh L (1987) Construction of an obligate photoheterotrophic mutant of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803: inactivation of the psbA gene family. Plant Physiol 85: 1021-1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanjean R, Zuther E, Yeremenko N, Havaux M, Matthijs HCP, Hagemann M (2003) A photosystem 1 psaFJ-null mutant of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 expresses the isiAB operon under iron replete conditions. FEBS Lett 549: 52-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joset F, Jeanjean R, Hagemann M (1996) Dynamics of the response of cyanobacteria to salt stress: deciphering the molecular events. Physiol Plant 96: 738-744 [Google Scholar]

- Kanesaki Y, Suzuki I, Allakhverdiev SI, Mikami K, Murata N (2002) Salt stress and hyperosmotic stress regulate the expression of different sets of genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 290: 339-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klughammer B, Sültemeyer D, Badger MR, Price GD (1999) The involvement of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase subunits, NdhD3 and NdhF3, in high-affinity CO2 uptake in Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 gives evidence for multiple NDH-1 complexes with specific roles in cyanobacteria. Mol Microbiol 32: 1305-1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kügler M, Jänsch L, Kruft V, Schmitz UK, Braun H-P (1997) Analysis of the chloroplast protein complexes by blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE). Photosynth Res 53: 35-44 [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudenbach DE, Reith ME, Straus NA (1988) Isolation, sequence analysis, and transcriptional studies of the flavodoxin gene from Anacystis nidulans R2. J Bacteriol 170: 258-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudenbach DE, Straus NA (1988) Characterization of a cyanobacterial iron stress-induced gene similar to psbC. J Bacteriol 170: 5018-5026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Badger MR, Price GD (2002) Novel gene products associated with NdhD3/D4-containing NDH-1 complexes are involved in photosynthetic CO2 hydration in the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp PCC7942. Mol Microbiol 43: 425-435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäenpää P, Kallio T, Mulo P, Salih G, Aro E-M, Tyystjärvi E, Jansson C (1993) Site-specific mutations in the D1 polypeptide affect the susceptibility of Synechocystis 6803 cells to photoinhibition. Plant Mol Biol 22: 1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn PJ, Price GD, Maleszka R, Badger MR (2003) Inorganic carbon limitation and light control the expression of transcripts related to the CO2-concentrating mechanism in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Plant Physiol 132: 218-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Endo T, Ogawa T, Asada K (1995) Thylakoid membrane-bound, NADPH-specific pyridine nucleotide dehydrogenase complex mediates cyclic electron transport in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol 36: 661-668 [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Endo T, Schreiber U, Ogawa T, Asada K (1992) Electron donation from cyclic and respiratory flows to the photosynthetic intersystem chain is mediated by pyridine nucleotide dehydrogenase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol 33: 1233-1237 [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Endo T, Schreiber U, Ogawa T, Asada K (1994) NAD(P)H dehydrogenase-dependent cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803: a study of dark-starved cells and spheroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol 35: 163-173 [Google Scholar]

- Mulo P, Tyystjärvi T, Tyystjärvi E, Govindjee, Mäenpää P, Aro E-M (1997) Mutagenesis of the D-E loop of photosystem II reaction centre protein D1: function and assembly of photosystem II. Plant Mol Biol 33: 1059-1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami A, Kim S-J, Fujita Y (1997) Changes in photosystem stoichiometry in response to environmental conditions for cell growth observed with the cyanophyte Synechocystis PCC 6714. Plant Cell Physiol 38: 392-397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T (1991a) A gene homologous to the subunit-2 gene of NADH dehydrogenase is essential to inorganic carbon transport of Synechocystis PCC6803. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 4275-4279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T (1991b) Cloning and inactivation of a gene essential to inorganic carbon transport of Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Physiol 96: 280-284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T (1992) Identification and characterization of the ictA/ndhL gene product essential to inorganic carbon transport of Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Physiol 99: 1604-1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Pakrasi HB, Ogawa T (2000a) Two types of functionally distinct NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. J Biol Chem 275: 31630-31634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Price GD, Badger MR, Ogawa T (2000b) Mutation of ndh genes leads to inhibition of CO2 uptake rather than HCO3- uptake in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 182: 2591-2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Sonoda M, Shibata M, Ogawa T (2001) Localization of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 183: 4938-4939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omata T, Price GD, Badger MR, Okamura M, Gohta S, Ogawa T (1999) Identification of an ATP-binding cassette transporter involved in bicarbonate uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 13571-13576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandström S, Ivanov AG, Park Y-I, Öquist G, Gustafsson P (2002) Iron stress responses in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Physiol Plant 116: 255-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmetterer G (1994) Cyanobacterial respiration. In DA Bryant, ed, The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 409-435

- Schmitz O, Tsinoremas NF, Schaefer MR, Anandan S, Golden SS (1999) General effect of photosynthetic electron transport inhibitors on translation precludes their use for investigating regulation of D1 biosynthesis in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. Photosynth Res 62: 261-271 [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem 68: 850-858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Katoh H, Sonoda M, Ohkawa H, Shimoyama M, Fukuzawa H, Kaplan A, Ogawa T (2002a) Genes essential to sodium-dependent bicarbonate transport in cyanobacteria: function and phylogenetic analysis. J Biol Chem 277: 18658-18664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Ohkawa H, Kaneko T, Fukuzawa H, Tabata S, Kaplan A, Ogawa T (2001) Distinct constitutive and low-CO2-induced CO2 uptake systems in cyanobacteria: genes involved and their phylogenetic relationship with homologous genes in other organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 11789-11794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Ohkawa H, Katoh H, Shimoyama M, Ogawa T (2002b) Two CO2 uptake systems in cyanobacteria: four systems for inorganic carbon acquisition in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Funct Plant Biol 29: 123-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, McIntyre LM, Sherman LA (2003) Microarray analysis of the genome-wide response to iron deficiency and iron reconstitution in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol 132: 1825-1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanier RY, Kunisawa R, Mandel M, Cohen-Bazire G (1971) Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol Rev 35: 171-205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus NA (1994) Iron deprivation: physiology and gene regulation. In DA Bryant, ed, The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 731-750

- Suzuki I, Kanesaki Y, Mikami K, Kanehisa M, Murata N (2001) Cold-regulated genes under control of the cold sensor Hik33 in Synechocystis. Mol Microbiol 40: 235-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinnemeier J, Hagemann M (1999) Identification of salt-regulated genes in the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 by subtractive RNA hybridization. Arch Microbiol 172: 377-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinnemeier J, Kunert A, Hagemann M (1998) Transcriptional analysis of the isiAB operon in salt-stressed cells of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEMS Microbiol Lett 169: 323-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JGK (1988) Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis 6803. Methods Enzymol 167: 766-778 [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Hua Q, Shimizu K (2002) Metabolic flux analysis in Synechocystis using isotope distribution from 13C-labeled glucose. Metab Eng 4: 202-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Zhao JD, Mühlenhoff U, Bryant DA, Golbeck JH (1993) PsaE is required for in vivo cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Plant Physiol 103: 171-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Paakkarinen V, van Wijk KJ, Aro E-M (2000) Biogenesis of the chloroplast-encoded D1 protein: regulation of translation elongation, insertion, and assembly into photosystem II. Plant Cell 12: 1769-1781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]