Abstract

Research in human genetics and genetic epidemiology has grown significantly over the previous decade, particularly in the field of pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics presents an opportunity for rapid translation of associated genetic polymorphisms into diagnostic measures or tests to guide therapy as part of a move towards personalized medicine. Expansion in genotyping technology has cleared the way for widespread use of whole-genome genotyping in the effort to identify novel biology and new genetic markers associated with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic endpoints. With new technology and methodology regularly becoming available for use in genetic studies, a discussion on the application of such tools becomes necessary. In particular, quality control criteria have evolved with the use of GWAS as we have come to understand potential systematic errors which can be introduced into the data during genotyping. There have been several replicated pharmacogenomic associations, some of which have moved to the clinic to enact change in treatment decisions. These examples of translation illustrate the strength of evidence necessary to successfully and effectively translate a genetic discovery. In this review, the design of pharmacogenomic association studies is examined with the goal of optimizing the impact and utility of this research. Issues of ascertainment, genotyping, quality control, analysis and interpretation are considered.

Keywords: Epistasis, genotyping, personalized medicine, pharmacogenomics, quality control, statistics, study design

1. INTRODUCTION

The term pharmacogenomics describes the study of how genetic variation modulates the response of the human body to therapy. The goal in conducting pharmacogenomic research is to find variants which account for the high level of interindividual variability in response to drug treatment, whether that response is an adverse drug reaction (ADR), blood drug level, or general efficacy of the treatment. Prevention of serious adverse reactions is paramount to improving treatment outcomes, as it is estimated that such reactions are responsible for 4–5% of hospital fatalities [1]. Pharmacogenomic research holds the possibility of shaping personalized medicine by allowing medical decisions of treatment to be based upon the private suite of variation present within the patient’s genome. By elucidating the genetic determinants of variation in drug response, safe and effective treatment decisions can be made without the necessity of trial and error. The study of pharmacogenomics has been made possible by the large expansion of the field of human genetics over the past several decades. This expansion has been driven by the discovery of novel genetic variation coupled with innovations in genotyping technology. From the discovery of the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) in 1980 [2] to the that of the microsatellite [3] and, more recently, widespread utilization of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [4], genotypic markers have served to bolster our understanding of the segregation of disease loci and the impact of human genetic variation.

A SNP is a single base-pair change in the genetic code. SNPs are distributed in the genome at a density of one every 1000 base-pairs on average [5]. The most recent addition to the genetic epidemiology toolbox, copy number variants (CNVs) have become a focus of intense interest during the last few years [6]. CNVs are genomic regions of greater than 1000 base-pairs which are represented at a different number of copies than are found in the reference genome [7]. The terms marker and variant are used interchangeably and can refer to any indicator of genetic variation. Although the discovery of new markers of genetic variation has been paramount to advancing the field of human genetics, the true catalysts have come in the form of large-scale research projects such as the Human Genome Project [8, 9] and the International HapMap project [10]. The HapMap project, by documenting the patterns of variation across multiple populations, introduced two important concepts essential to establishing the currently-used large-scale genetic association studies, namely that there are long stretches of linkage disequilibrium (LD) across the genome and that these blocks of LD vary between populations [11].

Linkage disequilibrium is a phenomenon whereby there is an association between alleles at multiple genetic loci [12]. Due to the patterns of LD within the genome, it was found that even though millions of variants exist, nearly all common variation could be assayed in a European population by genotyping approximately a half million specifically selected SNPs known as tag SNPs [11]. These tag SNPs became the key to performing genome wide association studies (GWAS), which rely on the common disease common variant (CDCV) hypothesis.

The CDCV hypothesis states that most of the heritability of common disease is the result of risk alleles commonly found in the population [13]. Heritability describes the proportion of the variance in a trait or disease that is explained by genetics. In many cases, our current estimates of trait heritability derive from twin studies in which the concordance in phenotype between monozygotic (identical) twins is compared with that between dizygotic (fraternal) twins [14]. If the trait or disease has a significant genetic etiology, we should expect to see higher concordance between monozygotic twins. GWAS rely on LD between SNPs which are typed on genotyping platforms and the true susceptibility loci which modulate the trait of interest. Although it can be argued that GWAS has experienced great success in finding novel biology related to the underpinnings of many diseases [15, 16, 17], it has not been the panacea that was promised in some reviews written prior to widespread use of the GWAS design [18, 19]. Most genetic variants which have been associated with disease outcomes have remarkably small effects in terms of increasing the risk of disease or explaining the heritability of the trait [20]. As a result of these small effect sizes, the majority of associated variants discovered by GWAS have diminishing value for use in disease prediction. There are, however, a few examples of common diseases for which large genetic effects have been found, both from linkage studies and genetic association studies. Linkage studies use family pedigree information to look for co-segregation of a genetic locus with disease status [14]. The link between Alzheimer’s disease and the APOE gene is a good example of a strong effect found from linkage analysis [21, 22] while the effect of polymorphism in the CFH gene on risk for Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) was found simultaneously through genetic linkage and genetic association [23, 24, 25].

This paper examines the design of pharmacogenomic association studies with the goal of optimizing the impact and utility of this research. In particular, the issues of ascertainment, genotyping, quality control, analysis and interpretation are considered.

2. GENETIC ASSOCIATION STUDIES

Discoveries such as those in the case of APOE, for which the ε4 allele is associated with a 4-fold increase in risk for late-onset Alzeimer’s disease [26], and CFH, where individuals homozygous for the Y402H polymorphism have a 7.4-fold increase in risk for AMD [25], seem to be the exception rather than the rule when variants predisposing risk to common disease are concerned. There are several hypotheses as to why variation discovered up to this point has explained such a low proportion of the heritability for common diseases and ideas concerning where the remaining heritability could lie. One such explanation lies in the common disease, rare variant (CDRV) hypothesis [27] which states that the genetic burden of common diseases is most likely the result of multiple rare variations in common genes or pathways. This is a hypothesis which cannot currently be rigorously tested due to the dearth of knowledge about rare variation. Although GWAS data will not answer questions regarding the CDRV hypothesis due to its focus on common variation, whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing technologies are currently experiencing expanded use and [28] should allow the veracity of the CDRV hypothesis to be assessed. Another explanation for the lack of heritability accounted for so far with genetic association study results is that such association studies have failed to account for the complex genetic architecture which is likely to underlie common diseases [20, 29]. Most genetic association studies - particularly GWAS - have focused their analysis on the discovery of monogenic risk. By restricting analysis to single genetic variants at a time, these association studies have discarded the possibility of interactions between risk loci – also known as epistasis – which could be the key to at least part of the risk for disease.

The term epistasis refers to the phenomenon of gene-gene interactions and has three general definitions which have been proposed by Phillips in his review of epistasis [30]. The first definition, referred to as functional epistasis, describes the situation in which two proteins or molecular components interact within the cell. This type of epistasis is detected by molecular techniques such as yeast two-hybrid assays and chromatin immunoprecipitation and should be influential in complex drug metabolism networks. However, because functional epistasis implies considerable knowledge about the relationship of molecular components, it is often not possible to draw conclusions about its presence without downstream functional analysis in a model organism system such as mouse, yeast or cell culture.

The first description of epistasis in the literature is in the form of an allele at one locus masking the effect of an allele at a second locus. Bateson observed this phenomenon as a departure from Mendelian inheritance ratios in mouse coat color in 1909 [31] and it has now become known as compositional epistasis. While compositional epistasis can be clearly defined in model organisms with a common genetic background, in human populations with diverse genetic profiles it is difficult to discern an event of compositional epistasis. The definition of epistasis most relevant to the study of genetic epidemiology and pharmacogenomics is that of statistical epistasis, in which the risk predisposed by having two genetic variations simultaneously is not additive on a log scale from the risk of having the two risk variants separately. Due to the extensive complementation of genes and the complexity of gene networks involved in drug metabolism and clearance, it is entirely reasonable to assume that in many cases more than one genetic variation will be required to observe a phenotype such as the breakdown of a drug’s efficacy or an adverse drug reaction (ADR). This hypothesis is supported by the lack of phenotype seen in many knock-out mice [32, 33], loss-of-function yeast strains [34, 35, 36] and null mutants of Arabidopsis [37]. The importance of gene-gene interactions in nature is implicated by the results of extensive two-hybrid experiments conducted in yeast [38, 39].

Despite the seemingly pervasive nature of epistasis, it has been difficult to demonstrate the presence of influential gene-gene interactions in humans. This could be due, in part, to the lack of emphasis placed on searching for epistatic effects during the analysis phase of genetic association studies. This lack of interest in epistasis is prevalent despite theoretical work which shows that interactions could explain large proportions of trait heritability [40].

Other postulates for the unclaimed heritability in common disease include such phenomena as genetic heterogeneity, gene-environment interactions, and inflated heritability estimates [29]. Genetic heterogeneity refers to the presence of multiple separate genetic factors underlying the etiology of a trait. For example, two patients might experience adverse effects from the same drug where one results from a variant in the metabolizing enzyme which renders it unable to properly process the drug, leading to upstream buildup of a toxic intermediate and the other from failure to transplant that same toxic intermediate to the metabolizing enzyme as a result of a mutation in a membrane-bound transporter. Alternatively, there could be multiple mutations within the same gene which will cause a similar phenotype. Even Cystic fibrosis, which has a Mendelian inheritance pattern, has been found to result from over 1700 different mutations in the CFTR gene in different patients [41]. The complexity of human genetic architecture and our distinct genetic backgrounds makes it highly probable that genetic heterogeneity will be a significant basis of the etiology of heritable human diseases and traits. It might also be reasonable to blame the phenotypic heterogeneity and the misspecification of disease status for some of the inability to discover the underlying genetic causes of common disease [29].

3. GENETIC ASSOCIATIONS AND PHARMACOGENOMICS

While many genetic association studies of common disease have failed to uncover variation of attributing large effects, pharmacogenomic association studies have comparatively realized a great deal of success. Many influential variants have been discovered through association studies, particularly those in cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes. The CYP genes encode for a family of drug metabolism enzymes which are located largely in the liver and account for approximately 90% of drug oxidation in human metabolism pathways [42]. Multiple strong associations have been found between variation in CYP genes and pharmacogenomic outcomes. Of particular note are links found between SNPs in CYP3A5, CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 and response to the drugs tacrolimus [43], efavirenz [44], and clopidogrel [45, 46], respectively. Possibly the most influential associations exist between SNPs in the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes and warfarin pharmacokinetics. Warfarin is a commonly prescribed anticoagulant which has high interindividual variability in effective dose [47] and a narrow therapeutic window. Individuals with concentrations of warfarin over the target international normalized range (INR) have an increased risk of major bleeding events. Conversely, warfarin levels below the target INR will not be effective in treating the thromboembolism and systemic embolism conditions for which warfarin is prescribed [48]. The CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 alleles which result in amino acid change in the enzyme are associated with reduced warfarin metabolism rate [49] and this association explains as much as 10% [50] of the variance in warfarin dose response. The VKORC1 gene encodes vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1, for which the function is to activate vitamin K [51] and in turn modulate proteins involved in blood clotting. Variation in VKORC1 is responsible for up to 25% of the variation in the dose response of warfarin [50].

There is potential for comparatively fast translation from bench to bedside with pharmacogenomic research, which is also illustrated by HLA-B*5701 testing for hypersensitivity reaction (HSR) resulting from abacavir treatment in HIV-infected patients [52]. HLA-B*5701 testing is an ideal diagnostic due to its 100% negative predictive value (NPV) [52]. Although such an ideal pharmacogenomic test is not likely to be seen again in the near future, we can learn from the translation of the HLA-B*5701 discovery so as to accelerate utilization of future discoveries. In particular, points about HLA-B*5701 testing which drove its acceptance include the easily observed improvement in treatment outcomes which accompanied the prevention of the sometimes fatal HSR and the easily interpretable monogenic (i.e. the result of a single genetic variation) nature of the test. It is important to note here that this does not restrict future genetic tests to be monogenic; the key point is interpretability of results which can be translated to improve patient outcomes. Even a complex genetic test could achieve these goals if the correct architecture were put in place to relay the results to a clinician in such a way as to allow for an easy adjustment of their decision for medical treatment. Therefore, it is likely that bioinformatics infrastructure will become essential to maximize the utility and accuracy with which pharmacogenomic results are utilized. The question now should be posed: how do we optimize a pharmacogenomic study in order to most effectively answer the scientific question and maximize the potential downstream effect? The answer will, of course, depend on the question asked by the study however common considerations can be made. The first issue to come under consideration must be the design of the study. While a carefully designed pharmacogenomic study has the potential to yield novel knowledge about the treatment or phenotype in question, a poorly designed study can waste time, money, and generate spurious results which will incorrectly direct future research. It is not to say that a well-designed study does not have the potential to suffer failure, but bearing in mind aspects of study design and analysis minimizes the chances of such a failure.

4. STUDY DESIGN

4.1. Phenotype Definition

The first aspect of study design to solidify is that of phenotype definition. In general, there are two possible types of traits to study in pharmacogenomics: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacokinetics is the term used to describe drug processing including absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) [53]. An example of a pharmacokinetic trait studied for genetic associations is the concentration-dose ratio [54, 55, 56], the plasma concentration of a drug normalized to the dosage given and often corrected by the weight of the study participant. Other pharmacokinetic parameters [57] include drug clearance and excretion rates. Pharmacokinetic outcomes provide the capability to assay the function and performance of the ADME process. While pharmacokinetics attempts to describe the actions the body performs on a drug, pharmacodynamics refers to the manner in which the drug acts on the body [58]. In its narrowest sense, pharmacodynamics looks at the ligand-receptor activity of the drug. Because ligand-receptor interaction dynamics are difficult to study on a large-scale basis, it is significantly more reasonable to study side effects and efficacy.

Beyond classification as pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic, the outcome is defined and studied according to the form of its measurement. The four types of outcome measurement typically used in association studies are binary, continuously distributed, ordinal Poisson-distributed, and time-to-event.

Binary case-control dichotomization is the most commonly used phenotype in association studies. Common binary phenotypes include ADR and events such as myocardial infarction (MI) for which the drug under study was prescribed to prevent. While binary traits are convenient for association studies, they often have reduced statistical power - where power is defined as the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis of no association between the variant and the outcome when this hypothesis truly is false (i.e. when there exists a true association) - when compared to other outcomes [59]. A binary definition of ADR, for example, ignores differences which might exist in the severity of the reaction between individuals which could itself be influenced by genetic variation. As a result, a continuously distributed trait is preferable to a dichotomization when available [60, 61]. Change in blood lipid levels in the study of statin use, for example, would be preferable to simply identifying individuals with hyperlipidemia. Utilizing a continuous trait will also tend to reduce phenotypic heterogeneity and misclassification [62]. It could be that the least severe cases as defined by adverse drug reactions are not significantly different from some of the borderline controls who do not experience the necessary threshold of severity or that controls could go on to later become cases. These potential binary misclassification issues serve to muddy the waters and reduce statistical power to find genetic variants associated with the outcome. A continuously distributed trait which is often available from clinical trials and other studies in patient populations is dose-normalized drug concentration. This is particularly true for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index such as warfarin, and the immunosuppressant, tacrolimus, for which reaching the target drug level is imperative to the success of drug treatment.

As opposed to binary- or continuously-defined outcomes, event counts and rates, which follow a Poisson distribution, are not often used outside of traditional epidemiological studies. An example of the use of such an outcome is demonstrated in the 2010, Crum-Cianflone et al. study of factors modulating hospitalization rate in HIV-1 infected patients [63]. In this study, the researchers examined the rate of hospitalization in a cohort of HIV-1 patients over a fixed period of time and how rates varied as a function of variables such as CD4 T cell count and presence of concurrent infections. Outcomes defined by a rate attempt to examine an ordinal measure such as a count normalized over a period of time. Utilizing a rate as the phenotypic measure in pharmacogenomic association studies also has an advantage over binary classification when possible. The rate of ADR occurrences or even hospitalizations due to ADR in a participant would be more descriptive than an indicator of the presence or absence of a reaction. While the use of rate-based outcomes in pharmacogenomic association studies is still rare, survival/time-to-event measures are commonly assessed. This is particularly true when examining the potential for long-term benefit from guiding drug treatment by genetic testing [64, 65]. Example study endpoints include survival time of individuals with colorectal carcinoma [66] and time to drug resistance in HIV-infected individuals on ART [67]. The dimension of time lends valuable information which would be lost if the binary clinical phenotype were taken at the end of follow-up and also alleviates issues of loss to follow-up through the use of censoring [68].

4.2. Treatment-Dependent and Treatment-Differential Study Designs

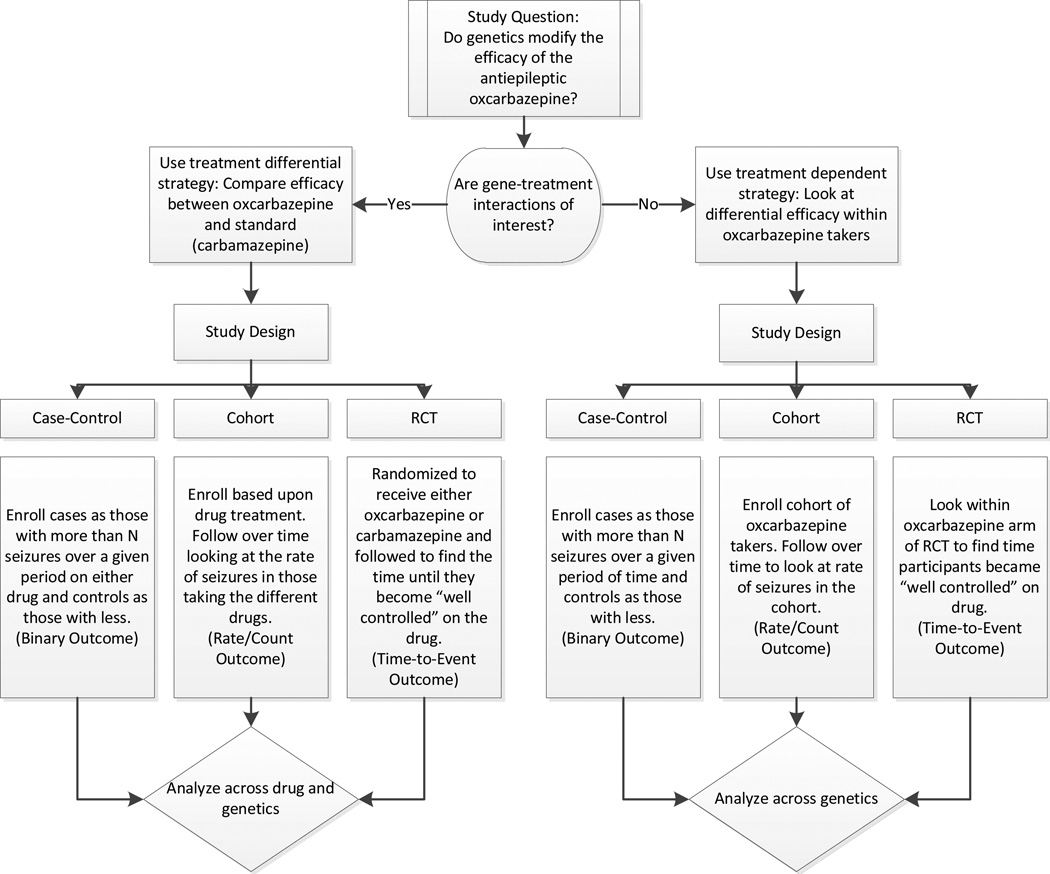

Pharmacogenomic association studies can be conducted in two ways with respect to treatment regimen: treatment-dependent and treatment-differential. The treatment-dependent study looks only at individuals on the drug of interest and examines variation among these individuals with respect to the outcome under investigation. In contrast, a treatment-differential study assesses two groups of individuals differing in their treatment and is useful for exploring gene-treatment interactions. Some outcomes, such as ADR, require the use of the drug or treatment being researched and therefore must be pursued with a treatment-dependent study. Other endpoints can be pursued in either a treatment-dependent or treatment-differential manner. Associations between HIV antiretroviral drug efficacy and genetics, for example, could be tested either by looking across drug treatment regimens, as is done in many AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) trials through assessment of mechanisms by which genetics and regimen interact to modulate a decrease in HIV viral load, or by scrutinizing patients on a single regimen and correlating patterns of genetic variation with efficacy. Treatment-dependent and treatment-differential study strategies to answer an example research question are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of treatment dependent and treatment differential study designs answering a harmacogenomic question related to antiepileptic drug efficacy.

4.3. Study Designs

Three study designs form the basis on which most pharmacogenomic association studies are conducted: the case-control study, the cohort study and the randomized clinical trial (RCT) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Major study designs utilized in genetic association studies

| Study Design | Case-Control | Cohort | Randomized Clinical Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Good for rare outcomes | Reduced recall and selection bias | Reduced recall and selection bias |

| More cost effective | Availability of longitudinal measures | Availability of longitudinal measures | |

| Can be performed within a cohort or RCT using nested case-control or nested case-cohort | Possible availability of repeated measures | Possible availability of repeated measures | |

| Flexibility to pursue multiple outcome types | Flexibility to pursue multiple outcome types | ||

| Direct estimate of risk from exposure | Direct estimate of risk from exposure | ||

| Randomization reduces confounding | |||

| Disadvantages | Recall bias -Treatment and adherence data may not be accurate -Accuracy can differ by case status |

Difficult to study rare outcome | Difficult to study rare outcome |

| Usually costly due to prospective nature | Costly due to prospective nature | ||

| Suffers from loss to follow-up | Suffers from loss to follow-up | ||

| Selection bias -Survival time bias -Cases and control not from same population |

|||

| Controls could develop outcome in the future | |||

| Estimating odds of exposure given outcome | |||

| Possible Study Outcomes | Binary | Binary | Binary |

| Continuous | Continuous | ||

| Time-to-Event | Time-to-Event | ||

| Rate/Count | Rate/Count |

The most prevalent study design used in genetic association studies is the case-control design. A case-control study involves the ascertainment of participants by their outcome status followed, typically, by a retrospective look at exposures of interest [69]. The term exposure, in this case, can refer to environmental factors such as smoking and diet or to genetic factors. In a pharmacogenomic case-control study, the frequency of a genotype or allele is compared between cases and controls in the interest of elucidating genetic markers predisposing a change in the odds of experiencing the outcome of interest [70]. The risk estimate derived from a case-control study is the odds ratio (OR). The OR describes the odds of an exposure in cases with respect to that in controls. In most situations, cases are defined by the presence of an ADR or other drug-dependent event and the exposure refers to genotype. For treatment-differential studies the exposure is often a treatment-genotype interaction. This would be true for a study of MI-prevention through the use of statins in comparison with aspirin, where the presence of a MI event would define cases and the exposure to test for association would be the interaction between statin use and genetic variation. Although the OR is not equivalent to the risk ratio (RR), an estimate of disease risk in individuals with the exposure as compared to those without, it is a reasonable approximation if the outcome is rare.

Benefits of the case-control study design include the potential to study rare diseases for which other designs would not be able to collect sufficient sample sizes in addition to cost-efficiency, as a case-control design alleviates the expense of follow-up [69]. There are also several potential weaknesses to the case-control study design [69]. The most concerning issue is the potential for selection bias attributed to the ascertainment process of case-control studies. Selection bias can result from differential survival if the cases are not all newly incident, meaning that the cases ascertained represent a subset of those who have survived to the time at which enrollment became possible or a subset still capable of enrolling. Selection bias could also arise from a failure to select cases and controls representative of the same population. In addition to selection bias, case-control studies can suffer from information bias a s a consequence of differential ascertainment not of the participants themselves, but of study variables. Information on exposures could be collected asymmetrically by researchers possibly due to knowledge about case-control status. Sometimes information bias is completely unintentional, as with recall bias. Recall bias results from cases being more or less likely to correctly recall details of drug treatment or environmental exposures.

While the case-control study ascertains participants based on outcome, a cohort study enrolls participants predicated upon exposure status and follows participants to evaluate study endpoint(s) [71]. Participants would be recruited based on their drug treatment in a pharmacogenomic cohort study either as a single treatment cohort or as part of multiple treatment cohorts in the interest of exploring gene-treatment interactions. Traditionally, cohort studies are conducted prospectively, with information on exposures collected prior to appearance or measurement of study endpoints although it is also possible to perform the study retrospectively [72]. The key defining feature of the cohort study is that ascertainment proceeds on the basis of the exposure - the drug treatment - instead of the endpoint. Cohort studies have several advantages over case-control studies. First of all, because individuals are recruited directly for their exposure, the relative risk associated with an exposure can be directly estimated [72]. Although the enrollment of study participants does not typically rely upon genetic information, cohort studies are still capable of deriving an accurate estimate of the relative risk of genetic variants. In addition, the longitudinal nature of cohort studies provides the ability to research survival time and rates. The issues of recall bias in prospective cohort studies are diminished as are those of selection bias, although information bias can exist with respect to treatment status [73]. For example, researchers might collect more complete information on individuals of a certain treatment group because of implicit assumptions regarding differential values of the study endpoint within that group. While many biases are reduced with the cohort design, the challenge of loss to follow up is introduced, placing emphasis on the importance of DNA collection early in the study to avoid bias in the form of a non-representative participant subset with DNA available for a pharmacogenomic association study [73]. Two particular areas in which cohort studies have a disadvantage in comparison with case-control studies are in cost and the capability to study rare outcomes [71]. Following individuals over the long periods of time - sometimes years - necessary to properly assess the study question is costly, however cohort studies are the best equipped to answer such questions regarding longitudinal outcomes provided that the outcome is sufficiently common. If the outcome were not common and only occurred in 1% of the population, 1000 study participants would be required on average to observe 10 who experience that outcome, making a well-powered study unfeasible. While prospective cohort studies are preferred for studying events with a dimension of time, continuously distributed traits benefit from the use of a retrospective cohort study. For a continuous trait, a cohort of individuals is enrolled based on their prior drug exposure status and then information on the trait is collected. Through the use of medical records, it should also be possible to study the change in a trait over time from the initiation of drug treatment through the time of ascertainment.

The gold standard of study designs in treatment-related research is usually considered to be the randomized clinical trial (RCT). An RCT randomizes the individual enrolled to receive one of multiple treatment arms [74]. This randomization process is useful in reducing selection bias and confounding [75]. Confounding is a situation whereby a factor is associated with both the outcome and the exposure but is not in the causal pathway [76]. Failure to account for confounding can lead to both false positive and false negative associations. The issue of confounding is exemplified by an epidemiology study looking at an association between alcohol consumption and lung cancer [77]. Without controlling for cigarette smoking, it appears that an association exists between alcohol consumption and lung cancer. After adjusting for cigarette use, however, it becomes clear that this association is due to confounding.

The most prevalent confounder in genetic association studies is genetic ancestry; this type of confounding is referred to as population stratification [78]. Population stratification is likely to be a significant issue in pharmacogenomic association studies, for which drug response can have strong ethnic disparities, and will be considered in depth during the discussion of quality control (QC). Randomizing individuals to treatment status reduces the likelihood that there will be an excess of individuals from a certain genetic ancestry within one treatment group and so the potential for confounding from this factor is reduced. Under the same rationale, the RCT design alleviates confounding from other factors as well.

Another advantage of the RCT is that it is typically conducted double-blinded, meaning that neither the researcher collecting data nor the study participant is aware of the treatment the participant has been randomized to receive [75]. The benefit of blinding is that it prevents information bias from data collection disparities across treatment groups. The assumption behind the use of blinding is that a participant’s knowledge of the study drug they receive might change their response or adherence and complicate comparability between treatment groups. Double-blinding is used to prevent the same effect on the part of the clinician, assuming that un-blinded knowledge might result in more carefully monitoring of participants on a particular treatment regimen. The double blinding procedure eliminates the heterogeneity and bias that these factors could contribute to a study. There are, however, inherent issues with the RCT design. In an RCT, the treatment designation for an individual typically refers to the intent-to-treat - the treatment that the participant was randomized to - and might not be the treatment which that participant received for the majority of the study due to treatment-related complications [73]. The RCT design also shares with the cohort design the issues of loss to follow up and is ineffective for the study of rare outcomes. It is also more difficult to study long-term outcomes with an RCT than a cohort study due to the large costs of maintaining an RCT [79, 80].

An additional concern when performing a genetic association study using RCT data is selection bias related to collection of DNA samples. Providing DNA within an RCT is encouraged but not required and only a subset of participants is likely to give consent for DNA. As a result, it is possible for bias to enter the study at this point due to the systematic exclusion of participant groups and it might not be reasonable to assume that randomization still holds. Comparing the demographics of the subset providing DNA samples to those of all study participants can determine the severity of the bias. Another challenge concerns the sample size of RCTs. Single-center trials often fall below the sample size requirement for a well-powered genetic association study and thus the inclusion of either multiple centers or multiple studies is necessary to achieve sufficient sample size. Combining multiple centers and/or studies has the potential to introduce heterogeneity with respect to both phenotype and genetic ancestry [73]. A benefit of RCTs with respect to DNA is that centralized repository sample storage is sometimes conducted for future use. The ACTG, for example, has gathered DNA in a sample repository for many years in the interest of implementing pharmacogenomic association studies [81].

Within data sets gathered from case-control, cohort and RCT study designs, specialized analysis schema are available to answer targeted scientific questions. For example, a binary outcome can be analyzed in RCT or cohort study data through the use of either a nested case-control or nested case-cohort design. The nested case-control study [73] defines cases as individuals within the larger cohort or RCT study who developed the outcome of interest, and controls as a random sample of the participants who did not develop the outcome. During the analysis, age is used to adjust for time-dependent differences between the cases and controls.

A variation of the nested case-control study, the nested case-cohort study matches one or more controls to each case on the basis of age or other time-related variables [73]. Another option, the case-only study, can be performed within case-control or nested case-control data sets and is useful for exploring gene-treatment interactions. In the case-only study, a measure of association between genotype and treatment group is explored [82, 73, 83]. This resulting risk estimate is a measure of the interaction between the genotype and the drug treatment. An assumption of case-only study is that the genotype and treatment group are independent. Due to the stringency of the assumption of independence, it is ideal to perform a case-only study within cases taken from an RCT.

5. GENOTYPING

5.1. Genome-Wide Association Studies

Recent innovations in genotyping technology have continually expanded the toolbox of the pharmacogenomic association study. Four genotyping schemes are typically used: candidate gene genotyping, specialized chip platform genotyping (candidate chip), genome-wide genotyping, and whole exome/whole genome sequencing. Each method has advantages, disadvantages and appropriate applications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of major genotyping approaches

| GWAS | Candidate Chip | Candidate Gene | Sequencing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of markers | Half million to Millions | Thousands to Hundred Thousand + | Tens to Hundreds | Millions |

| Use | Genome wide exploration of common genetic variation | Focused analysis of common or rare variation in many biologically plausible genes, | Focused analysis of common or rare variation in one or handful of genes, | Genome wide exploration of common and rare variation, |

| Hypothesis generation | Hypothesis generation or testing | Hypothesis testing | Hypothesis generation | |

| Advantages | Cost-effective genotyping | Somewhat alleviated multiple testing issues | Alleviated multiple testing issues | Detection of all types of variation within sequenced regions including ability to assess rare and functional variation |

| Unbiased coverage of common variation across genome | Biological plausibility of significant results | Focused biological hypothesis | Unbiased coverage of common variation across genome. | |

| Many markers allows for PCA-based substructure correction and more extensive QC | When more than 100,000 markers typed, PCA-based substructure correction possible | Potential to target functional and rare variants | Many markers allows for PCA-based substructure correction and more extensive QC | |

| Low overall cost | ||||

| Disadvantages | Not equipped to assess rare variation | Less cost effective than GWAS | Higher per-genotype cost | Currently cost-prohibitive for many samples |

| Millions of markers causes severe multiple-testing issues | When less than 100,000 markers typed, difficult to control for population substructure | Difficult to control for population substructure | Must sequence to high coverage to sequence all areas and offset error rate | |

| Relies on accurate biological knowledge | Limited QC possible | Millions of markers causes severe multiple-testing issues | ||

Genome-wide genotyping arrays employed in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become a standard for exploring the genetic etiology of complex human disease [84]. These arrays are designed to genotype 500,000 or 1 million tag SNPs by which it is possible to capture nearly all of the common variation in the human genome of European populations due to LD [11]. It should be noted that LD patterns vary between ethnicities [12] and therefore a tag SNP derived from a European population should not be expected to tag in an African population. The LD in African-derived populations tends to extend across much smaller genomic regions [85] and therefore typing more SNPs is required to achieve comparable genome-wide coverage to that for a European population. By some measures, GWAS has experienced great success in discovering genetic variation associated with risk for disease; approximately 1290 polymorphisms for nearly 250 outcomes have been found to be genome-wide significant [86] (p < 5 × 10−8).

As stated previously, however, nearly all of these associated variants explain only modest amounts of heritability. Issues with small effect size could reflect, in part, phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity. For many diseases which have been probed repeatedly with GWAS, significant variation exists in the phenotype definition and this variation is often ignored when categorizing individuals by disease status [87]. For multiple sclerosis (MS) for example, there are 4 different subtypes of the disease for which the neurodegenerative progression of the disease vary [88]. Due to sample size issues these 4 subtypes are nearly always combined [89] despite the possibility of different genetic etiology underlying each subtype. Genetic heterogeneity has been implicated in many other complex phenotypes which have been studied with GWAS [90]. Both genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity in a study population will tend to reduce statistical power and push risk estimates towards the null hypothesis of no association. Pharmacogenomic association studies have an advantage when phenotypic heterogeneity is concerned. The imposition of clinical standards for diagnosis of drug reactions and the measurement of pharmacokinetics will diminish heterogeneity in the outcome. Many pharmacogenomic studies have focused only on genomic regions with a priori ties to drug metabolism, such as the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of genes [91]. Due to the historically targeted nature of these studies, the use of GWAS has the potential to uncover novel population variation associated with the etiology of variable drug response and add to the predictive ability which currently-established associations already lend. Such novel biological discoveries could make it possible to design safer, more effective drugs [92] or to guide the prescription of drugs with known safety or efficacy concerns.

Although GWAS is useful for assaying common genetic variation, it is not yet equipped to handle rare variation. That may change soon, as development of genotyping arrays like those of the Illumina Omni series promise to enable genotyping of up to 5 million markers as well as the continued evolution of high throughput sequencing platforms (which will be discussed further in Section 5.4).

There are considerations to be made prior to performing a GWAS. In 2007, the NCI-NHGRI Working Group on Replication in Association Studies laid out requirements for replication prior to reporting GWAS results [93]. Replication will be discussed in detail in the post-analysis section of this review. One of the most significant challenges associated with GWAS is that of multiple testing. Generally in a GWAS, an uncorrected p-value of 5x10−8 is required to consider a result to be genome-wide significant. This stringent p-value cutoff requires a large sample size - often in the thousands - to detect a modest genetic effect. The issue of multiple testing and p-value corrections is covered in more depth later in the review.

5.2. Candidate Chip Genotyping

Alternative to using a genome-wide genotyping platform, specialized genotyping assays and arrays containing polymorphisms specific to a given trait are becoming popular. Examples of these specialized genotyping chips include the Affymetrix DMET Plus Premier Pack [94] and the Illumina HumanCVD BeadChip [95]. The Affymetrix DMET microarray chip is designed to genotype approximately 2000 markers in over 200 absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination (ADME) genes which are not well represented on genome-wide genotyping arrays. The population frequency of the polymorphisms on the chip range enormously and there is a significant focus on those mutations which are rare in the population. In personal experience with the DMET chip, of the 1936 markers which were typed on about 500 individuals, approximately 33% showed no variation in our study (unpublished results). It seems that the DMET chip would be better served by a larger study population to increase the probability of observing variation in low-frequency polymorphisms.

Another option is the HumanCVD chip, which is designed by Illumina to genotype 50,000 markers in 2100 genes implicated in functions and disorders tied to cardiovascular disease such as blood pressure, insulin resistance, metabolic disorder, lipid disorder, and inflammation. The markers on the HumanCVD chip are categorized into three groups of genes ranging from with high probability of playing a functional role in disease risk to those with only marginal ties to disease pathology.

In addition to widely available designer chips already created, many genotyping companies allow for the specification of custom-made chips. The Illumina ImmunoChip is an example of a genotyping array which was tailor-made to fit the purpose of looking at candidate variation in particular, potentially disease-linked genes1. The ImmunoChip was created as a custom chip in response to interest in looking at variation in genes linked to auto-immune disorders such as Lupus, Multiple Sclerosis and Rheumatoid Arthritis; the chip provides the capability to assess variation at approximately 200,000 markers finely distributed across the genes and genomic regions concerned1. Illumina provides a service, iSelect, which allows for the customized creation of chips with a number of variants ranging from either 3000 to 68000 or 68001 to 200,000. The Illumina VeraCode technology, in contrast, is designed to examine fewer SNPs and is utilized in the ADME Core Panel. The ADME Core Panel assays 184 ADME variants in 34 important drug metabolism genes.

There are multiple advantages to the application of these custom assays and arrays. First, employing prior biological knowledge to focus genotyping efforts yields a higher probability of discovering associated polymorphisms [96], especially when compared with genome-wide genotyping platforms which might not adequately assess the variation in regions of particular interest [97]. The biological knowledge which is used to decide the variants added to the platforms is a primary concern, though. In terms of the currently available arrays, extensive research was done to select genes to include and to ensure that these genes are sufficiently covered by variants on the chip [98, 95]. Another advantage which is specific to custom arrays is the ability for the user to add variants of their choosing, including those variants which have been discovered subsequent to the release of standardized genotyping platforms. There are several methods which are used in the selection of genes and polymorphisms to add to a genotyping array [99, 100, 101, 102]. The major disadvantages of the customized genotyping chips are increased ‘per-genotype’ costs and the initial work which is necessary to select markers for a new array. In addition, genotyping efficiency is likely to decline in custom-made chips designed by researchers when compared with arrays and assays designed by genotyping companies which contain SNPs validated for genotyping accuracy and efficiency.

5.3. Candidate Gene Genotyping

The benefit of studying pharmacogenomics is the abundance of prior knowledge regarding pathways of drug metabolism, transport and elimination. Most currently-known pharmacogenomic associations are the result of candidate genotyping founded upon knowledge of these pathways and employed through the use of a candidate gene study. The candidate gene study uses focused genotyping to assess variation at only a handful of genes [103]. In place of a genotyping array, a low-throughput technology such as Sequenom [104], TaqMan [105], or Illumina GoldenGate [106] is used. Although the era of GWAS has seen a decrease in the use of candidate gene association studies, the approach has had great success discovering variants with substantial effect in pharmacogenomics and complex disease [44, 23, 107, 108, 109]. The same general principles of the candidate chip apply here to the candidate gene study. The correct biological knowledge is essential to appropriately focus genotyping. The user can directly assay markers with proven functional impact at the transcript, protein or trait level or those which cause non-synonymous coding changes instead of relying on tag SNPs to detect indirect associations. One of the most significant advantages of a candidate gene study is the alleviation of the issue of multiple testing.

5.4. Sequencing

Genotyping technology has progressed in waves over the last several years as the cost per genotype has steadily fallen. Now, we stand on the precipice of affordable whole-genome sequencing technology. There are many factors driving the progress in genome sequencing, first of all being the 1000 Genomes project [28], an initiative to uncover 95% of genetic variants in the “accessible genome” with a population frequency of 1% or greater [5]. The accessible genome is the portion of the genome for which sequencing reads can be unambiguously mapped back to the NCBI reference genome and constitutes approximately 85% of the entire genomic sequence in the current build [5]. The NCBI reference genome is the work originally of the Human Genome Project [110] and more recently the Genome Reference Consortium, which has been filling gaps in the sequence and updating inaccurate sequence reads. In order to realize the goal of the 1000 genomes project, three sequencing pilot phases have already been conducted and the main phase is currently under way.

The three pilot phases consisted of performing low-coverage (2–6×) whole-genome sequencing on 179 individuals, deep whole-genome sequencing (42X average) coverage of 2 mother-father-adult trios and finally sequencing 906 genes at approximately 50X coverage in 697 individuals. The full 1000 Genomes project data will consist of deep sequencing of coding regions, low coverage whole-genome sequencing, and genome-wide genotyping of 2500 samples [5]. When sequencing the genome, 1× coverage corresponds to the generation of approximately 3 billion base-pairs of DNA and means that statistically each base in the haploid human genome was sequenced one time on average. Although significantly higher coverage is necessary to fully sequence the diploid human genome without appreciable gaps and identify genetic variants [111], by sequencing many individuals at a relatively low coverage the hypothesis of the 1000 Genomes project is that novel variation can be detected by examining multiple samples from the same population [5].

In addition to the proposed goal of uncovering novel variation, the 1000 Genomes project has placed an emphasis on describing variation in diverse populations. In all, 27 populations representing 5 major geographical regions are represented in the 2500 samples collected for the 4 phases of the 1000 Genomes project [5]. As a result, the 1000 Genomes project should significantly advance our knowledge about population-specific human genetic variation.

Beyond the 1000 genomes project, an incentive to improve genome sequencing technology exists in the form of a $10 million prize being offered by Archon X Genomics for the development of technology which can sequence 100 individuals in 10 days at a cost of no more than $10,000 per individual [112]. The eventual goal is to bring the cost of whole-genome sequencing down to $1000 per individual [113]. Although this goal may not be too far off, current prices for whole-genome sequencing are around $50,000 per sequence [114]. For most researchers, this cost precludes the ability to perform sequencing on a large sample of individuals. As such, large-scale whole-genome sequencing in genetic association studies has not yet become a reality.

In lieu of whole-genome sequencing, a cheaper and more focused alternative is whole-exome sequencing [115, 116, 117]. The exome describes the set of all exons in the human genome; all the regions of the genome which will be expressed. Exon-capture technology can be used to selectively sequence all protein-coding regions in the genome for the cost of about $5000 [114]. While this cost is much greater than that of genome-wide genotyping, it is also significantly less than whole-genome sequencing but still enables rare variant discovery. One of the most challenging aspects of sequencing is data management. The space required to store the data from a single sequencing run can be 1 terabyte (1024 gigabytes) or more [118]. In addition, after the sequencing data is gathered, bioinformatics infrastructure is necessary to extract genetic variants from the raw sequence. Because these variants are comingled with sequencing errors, this is a non-trivial task [119]. Allele frequency thresholds are required to distinguish a genetic variant from sequencing errors. Assessing structural variation such as CNVs adds an additional level of complexity, as the “break points” - genomic base-pair positions where the repeat begins and ends - of a CNV can vary between individuals [120].

If the challenges and expense associated with sequencing technologies can be overcome, they lend the possibility of capturing rare and novel genetic variants which cannot be discerned through the use of genome-wide genotyping arrays and other platforms designed with the current knowledge regarding mostly common variation. As the price of sequencing falls and data management procedures improve, sequencing will become an increasingly viable option to capture nearly all coding information in the human genome. The challenge, then, will be applying analytical methodology to determine how this genetic information maps onto complex pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic traits.

6. QUALITY CONTROL

Prior to the analysis stage of a pharmacogenomic association study, it is important to ensure that the data collected for analysis have been standardized under a set of quality control (QC) standards. The genetic data, in particular, require several checks of quality. Weale [121] describes, in depth, the potential QC measures for large-scale genetic data. Further information about conducting genotype data QC is given by Laurie et al. [122] on behalf of the GENEVA consortium or by Turner et al. [123] on behalf of the eMERGE network. Almost all of the QC discussed below can be conducted in the infrastructure of PLINK [124], developed at the Broad institute or in PLATO [125], developed at Vanderbilt University (http://chgr.mc.vanderbilt.edu/ritchielab/PLATO).

The rationale for conducting checks of quality surrounds the attempt to remove systematic error from the data which could otherwise bias the results of the analysis. Genotype QC standards and procedures can be broken down into those performed on samples and those performed on genetic markers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recommended QC steps prior to association analysis

| QC Process | Software | |

|---|---|---|

| Marker QC | Genotyping Completion Rate Filter | PLINK, PLATO, genABEL |

| Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Check | ||

| Minor Allele Frequency Filter | ||

| Sample QC | Genotyping Completion Rate Filter | |

| Heterozygosity Check/Filter | ||

| Gender Error Check | ||

| Relatedness Correction | ||

| Plate Effect Check | ||

| Population Stratification Adjustment | Genomic Control, EIGENSTRAT | |

| Population Outlier Removal | EIGENSTRAT, STRUCTURE |

If a stratified analysis will be conducted, QC should be conducted separately within each stratum if the stratifying variable is likely to be related to genetic variation, as is the case with race ethnicity. Three general approaches exist when considering the order by which sample and marker QC will proceed. Performing marker QC first will maintain the maximum number of participants in the study while placing sample QC first will maintain the variants over samples. A recently developed program, genABEL [126], allows QC on markers and samples to be done iteratively to balance low-quality losses from each. The choice of genotyping should be a consideration when deciding which route of QC to pursue. If a candidate gene study has been conducted, it would be prudent to do QC on samples prior to that on markers so as to ensure the minimal discard of functionally relevant genetic variants. Performing QC on markers first is reasonable for GWAS, though, as it is hypothesized that the vast majority of variants genotyped do not participate in the genetic etiology of the outcome. It is also possible with GWAS that multiple markers will be in LD with the functional variant they are tagging and thus the discard of one will not preclude the identification of a genomic locus associated with the outcome. One of the primary considerations for GWAS QC concerns the large sample size required for a GWAS to be sufficiently well-powered.

There are many QC checks and exclusion standards which could be applied to samples and markers [121]; the ones which will ultimately be used must depend on the data available. The first step is to check for gender errors and examine relatedness regardless of whether the focus is on maintaining samples or markers. If sex chromosome data is available, gender errors can be identified by checking the heterozygosity of the X chromosome back to the gender classification for each individual. For potential errors, it is desirable to determine whether the cause is misclassification or an aneuploidy - abnormality in chromosomal number - such as Kleinfelter syndrome through examination of raw genotype calls for X and Y chromosome marker intensities. If gender errors cannot be resolved - potentially through consulting medical records - as misclassification due to error in sample handling or data entry, it is advised to exclude these individuals from analysis.

Relatedness between individuals in the study is addressed next because interrelatedness between study participants can result in spurious associations when using statistical tests which assume independent observations. If participant relationships are known, as in pedigree data, software such as genABEL [126] or MQLS [127] can be used to adjust by utilizing a kinship matrix describing relatedness between all individuals. It is also possible to derive a kinship matrix using genABEL if relationships are unknown [128], as could be the case in association studies of unrelated individuals where cryptic relatedness - relatedness between individuals which is not known to the researchers [129] - could be an issue.

An alternative to correcting for relatedness is to remove one individual at random from each pair for which there is a high estimated identity by descent (IBD), which can be done with PLINK [124]. Identity by descent is a term which is used to describe the presence of the same allele at a genomic region as a result of inheritance from a common ancestor. Note that estimating the inbreeding coefficient and IBD or kinship coefficient can only be performed on samples for which there is sufficient genotype data and that these techniques are designed to be used with whole genome data.

To exclude low quality genotype data, the next step is the removal of samples and markers with a low genotyping completion rate or, put another way, a high rate of missing genotype data. Each sample and marker is passed through a filter to remove those which fall below a certain genotyping completion threshold; a threshold which is sometimes used is 95%, indicating that those samples and markers for which at least 5% of the genotype data is missing are removed. For GWAS, this threshold is often more stringently placed at 98–99%. Typically, markers are filtered first, followed by samples. This allows for the minimal exclusion of precious study samples. The second step is the exclusion of samples with levels of heterozygosity well outside of that expected due to chance variation (determined by inbreeding coefficient above or below certain thresholds). Low heterozygosity can be the result of inbreeding driving down the level of individual genetic variation and high heterozygosity might indicate contamination of the sample by foreign DNA, which would lead to excessively high levels of individual genetic variation [121]. For genetic marker data, it is recommended to remove variants with a low minor allele frequency, as there is significantly reduced statistical power to detect associations for these markers. The minor allele frequency threshold for removing variants will depend upon the sample size for the study; Weale suggests a cutoff of 10/N, where N is the sample size. Filtering SNPs by Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) is sometimes performed as well. SNPs for which the test of HWE yields a p-value below a certain value are removed from analysis.

Notably, there are debates as to whether a check of HWE should result in marker exclusion or whether it would be more appropriate to flag markers with a strong deviation from HWE so that they can be followed up if they are found to be associated with the outcome [130]. The argument for removing SNPs in disequilibrium is that they are likely to be the result of genotyping error and might cause spurious associations. On the other hand, one of the assumptions of HWE is that there is no selection acting on the population [131]. If a SNP is under positive or negative selection it will violate HWE but should not be removed as that selection could indicate a role of the variant in disease etiology. The final recommended QC check is the assessment of “plate effects” across genotyping chips [132], which can be done by comparing MAF [133] or genotyping completion rate for each plate to that of all others utilizing the genetic data which has been filtered by MAF and sample genotyping completion rate. Plate effects constitute a particular type of batch effect, which are discussed in depth by Leek et al [134]. Identifying plate effects is important, as they can indicate incorrect handling of DNA samples or errors during the genotyping process. The issue of batch effects recently garnered general attention in the scientific community when associations discovered in a study of human longevity [135] were demonstrated to likely be the result of batch effect and QC problems [136, 137].

After performing general QC exclusions, it is imperative to examine the presence of population substructure in the data. Population substructure refers to the phenomenon whereby multiple distinct subpopulations are present within the overall sample population [138]. A frequent population substructure issue in genetic association studies is population stratification, in which the distribution of subpopulations differs systematically by outcome [139]. This should be distinguished from the concept of admixture [140], which refers to the ancestral mixing of two populations, as is present in populations such as Mexican and African Americans. Population substructure is important to consider prior to analysis because it can confound the analysis and cause spurious associations under specific conditions. The conditions under which substructure is confounding are that the prevalence - or distribution in the case of a quantitative trait - of the outcome is different between the subpopulations in the dataset and these subpopulations also differ in allele frequency at markers unlinked to the trait of interest [61]. Due to frequent differences in drug response between ethnicities [141, 142, 143], discerning the presence of population stratification is particularly relevant for pharmacogenomic association studies.

An extreme example of population stratification would be looking at risk for an ADR in a mixed sample of European Americans and African Americans for which 90% of the cases with the ADR are African American and 90% of the controls are European American. In this case, even though the true prevalence of the ADR might be equal between the ethnic groups, an artificial difference is introduced as a result of the poor study design. Any marker which differed significantly in allele frequency between European and African Americans would be associated with the presence of an ADR, even though it might be that none of these markers are truly associated with risk of the outcome. Fortunately, many tools have been developed to mitigate the effect of population stratification [144, 145, 78, 146, 147, 148].

Historically, epidemiology studies have relied on stratification to eliminate confounding by race and other factors. Although this alleviates stratification to a degree, there are multiple disadvantages to race-stratification, the most significant of which is the drop in statistical power which results from sub-dividing the data set prior to analysis. In addition, self-described race might not be as accurate or precise as desired [149], particularly with individuals of an admixed population where the degree of mixed genetic ancestry can vary between individuals. Even in a strictly European population, where ancestry is often assumed to be mostly homogeneous, there can be genetic differences between individuals of southern and northern or eastern and western Europe [150]. Although race-stratification has serious disadvantages, it is often the only choice for the correction of population stratification in small-scale genetic association studies if ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) are not also typed. Alternative to stratifying by race, a study can adjust for the presence of the type of systematic differences between individuals in the study that are present with population stratification. The Genomic Control method [145] was proposed as a manner of performing this adjustment. Genomic Control attempts to identify an inflation factor, λ, using markers which are unlinked to the trait of interest. This inflation factor, which describes the inflation of genetic association test statistics as a result of systematic bias, is then used to correct the test statistics of all genetic association tests.

A more recently introduced correction for population stratification involves principal components analysis, which can be conducted through use of the EIGENSTRAT software [146]. EIGENSTRAT uses principal components vectors describing the overall population level genetic variation between individuals to provide an ancestry-corrected association statistic. In order to appropriately use EIGENSTRAT without correcting out the effect of truly associated genetic markers, it is recommended that EIGENSTRAT be run with AIMs or with a set of at least 100,000 genetic variants. Whether correcting for substructure by stratifying or through the use of software such as EIGENSTRAT, it is recommended that population outliers - individuals who do not cleanly group with any of the identified populations in the principal components analysis - are removed [121]. Population outliers can be visualized either by plotting principal components vectors [121] or by using the STRUCTURE program [151].

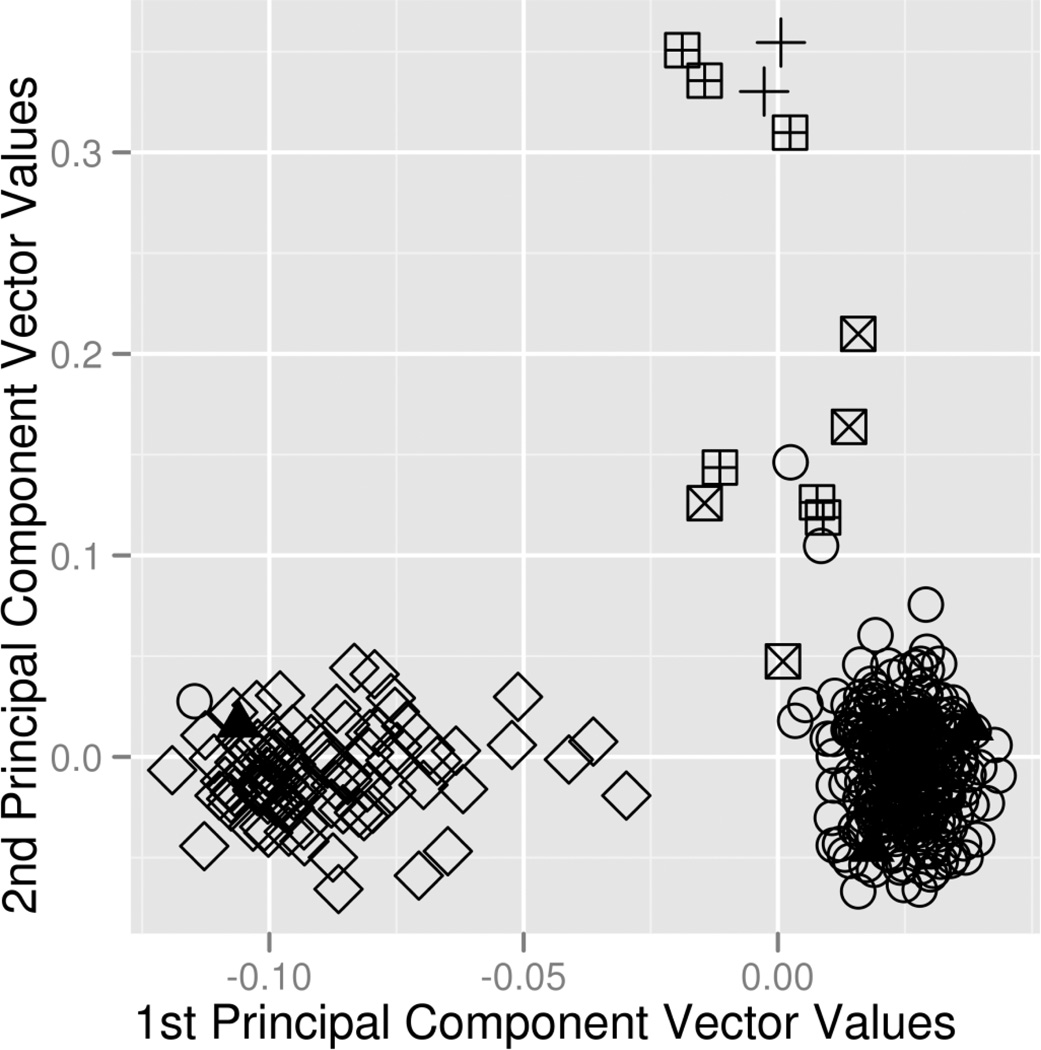

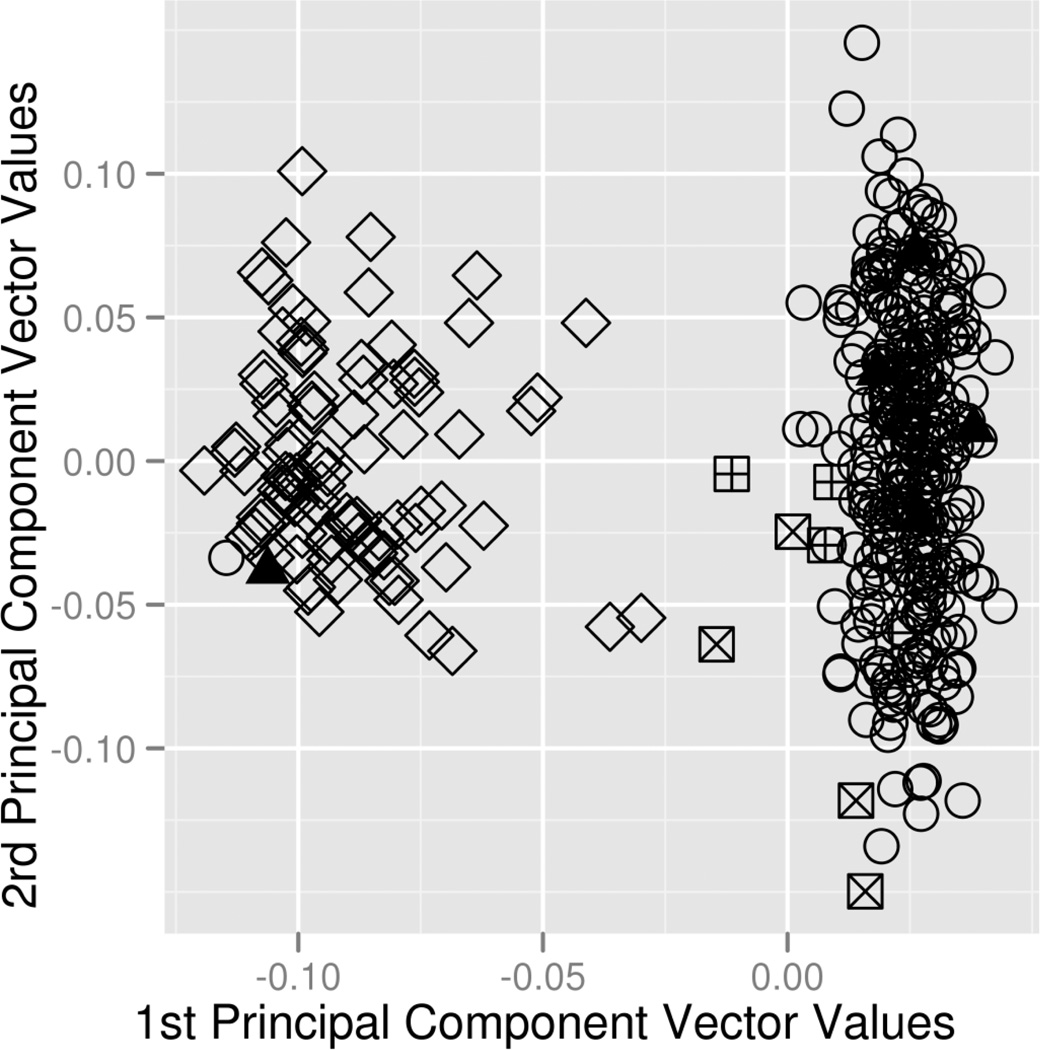

Principal components is used to describe systematic variation within data as attributable to a particular factor. When applied to genetic data in the attempt to account for race, one or more principal component vectors are generated where each vector places each study participant along a line for which the ends of the line describe the study participants differing most systematically by genetics related to race. If a principal component vector successfully describes systematic genetic differences attributed to race, plotting that vector should separate individuals out into two distinct clusters corresponding to a genetic split between ethnicities. Typically the two principal components explaining the most systematic variation are plotted (Figure 2a). When individuals cannot be cleanly clustered through the use of vectors, these outlier individuals should be removed (Figure 2b). Visualization of population outliers can be enhanced by the inclusion of data from relevant HapMap Phase 3 populations [121], which can clarify the axes of variation in a plot of principal components vectors by labeling individuals within the plot according to race. Including HapMap samples can also be used to map study participants more robustly to an ancestral population.

Figure 2.

The plots of the top two principal component vectors resulting from principal components analysis before and after removal of outliers and with true race coded by color. A) Prior to exclusion of outliers, there are several individuals who do not cluster cleanly. B) After outlier removal, the presence of two general clusters can be visualized. Open Diamond = African American; Open Circle = European American; Boxed Plus Sign = Asian; Boxed X = Hispanic; Plus Sign = Other; Filled Triangle = Unknown.

Performing appropriate QC on genotype data prior to association analysis is essential to providing accurate and robust results in a genetic association study. Failure to remove systematic error can result in a dramatic increase in false positive rate. Noise in the data can be an issue, in particular, due to the small effect sizes seen in many genetic association studies to date. It only takes a modest amount of noise to overpower the true associations in the data if they are of small effect size.

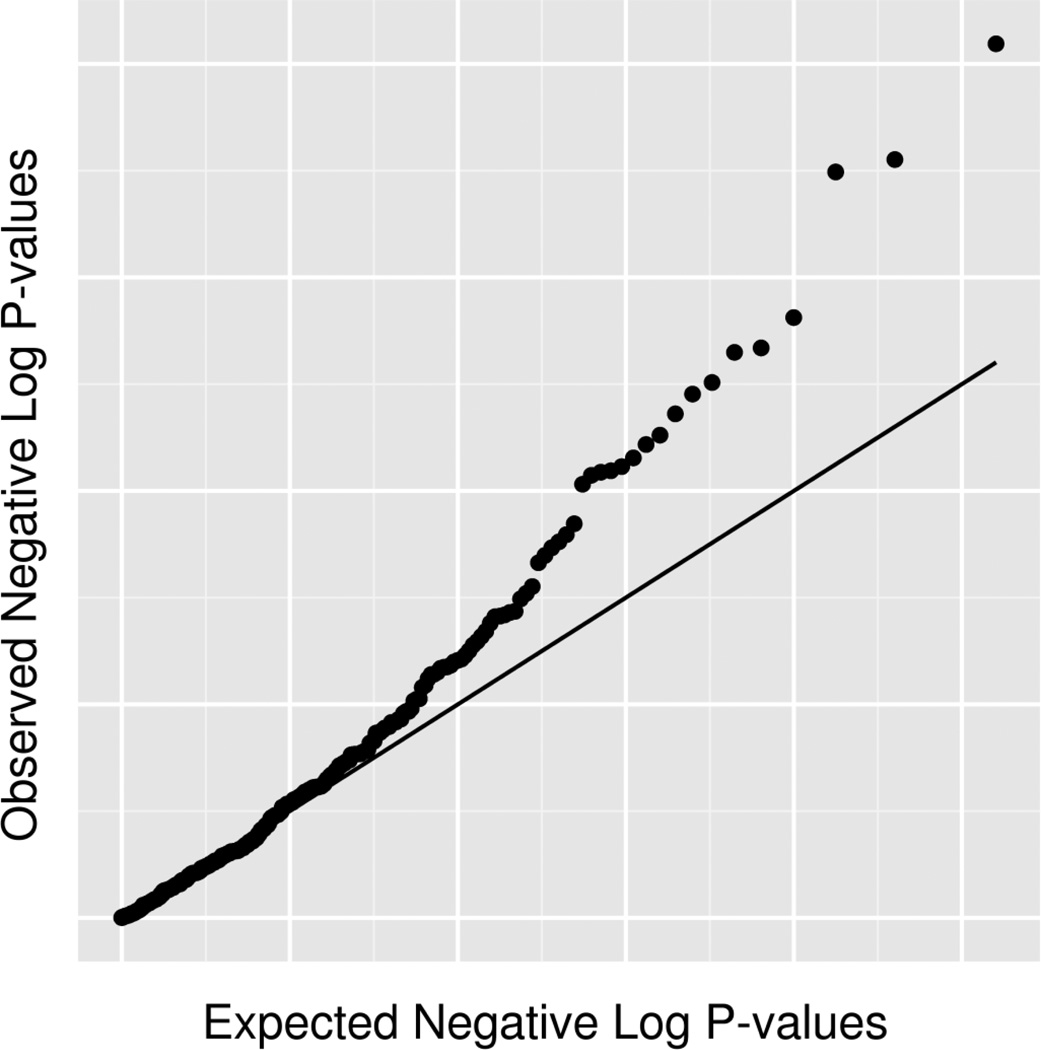

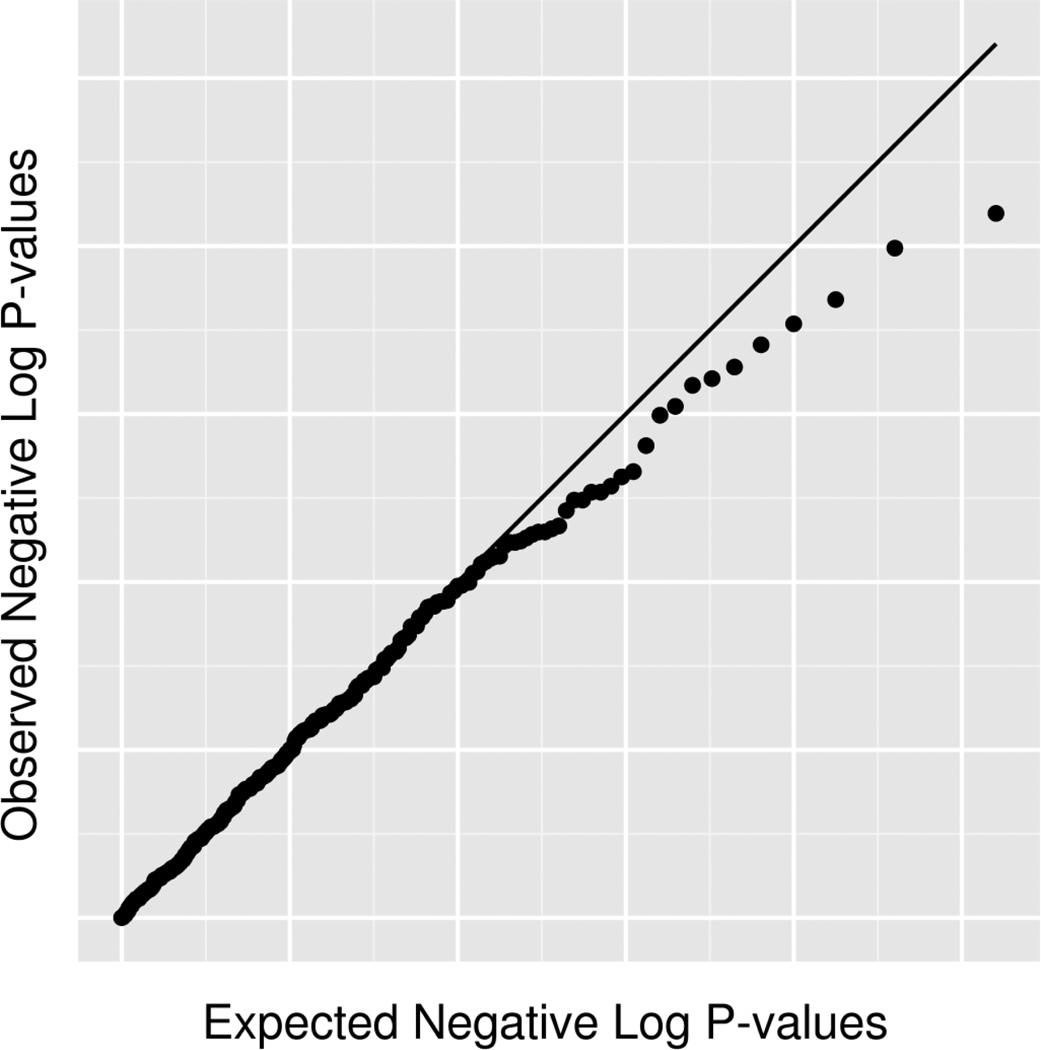

The use of quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots can help determine whether systematic error is present in the data [121]. Q-Q plots are generated by performing a test of association for each marker in the data and then graphing the resulting distribution of p-values - often using a negative log-transformation - against a set of the same number of p-values generated from a uniform distribution under the null hypothesis. Example Q-Q plots before and after quality control are shown in Figure 3a and 3b, respectively. If there is a systematic error in the data, it will often appear as a strong deviation from the diagonal line which would be expected under the null hypothesis of no association. After QC, it can be seen that no true association exists and systematic error was driving inflation in test statistics and p-values smaller than expected. Such plots act as a useful diagnostic and illustrate the need for thorough QC.

Figure 3.

Q-Q plots showing the negative log-transformed p-values for all SNPs in an association study. A) Before quality control, many association results have low p-values. B) Subsequent to quality control, it can be seen that the presence of a departure from expected p-values was likely the result of systematic bias from low quality data. The line demonstrates what would be expected if the null hypothesis of no association holds.

7. ANALYSIS

Analysis of pharmacogenomic data has the potential to proceed to many ends due to the complex nature and extensive amount of data available in most pharmacogenomic association studies. It is essential to carefully define an analysis plan designed to answer the question of interest in order to obviate statistical invalidity and minimize false positives. If enough analytical tests are performed on the data, statistically significant results will be found. Because performing a fishing expedition in a data set casts doubt on the results, the object of the analysis plan should be to focus statistical testing towards answering a defined scientific question.

Several questions should be considered when defining the analysis plan which will be used to answer the study question. Are only monogenic associations expected to be significant predictors of the outcome or could there exist significant gene-gene, gene-environment, or gene-treatment interactions? Should the initial set of genetic variants be filtered to a more interesting subset prior to performing statistical tests of association? Would prior biological knowledge be useful to include? Does a replication dataset exist which could be used to validate significant associations detected? What factors could be considered as confounders? If race might be a confounder, how should it the analysis be adjusted?

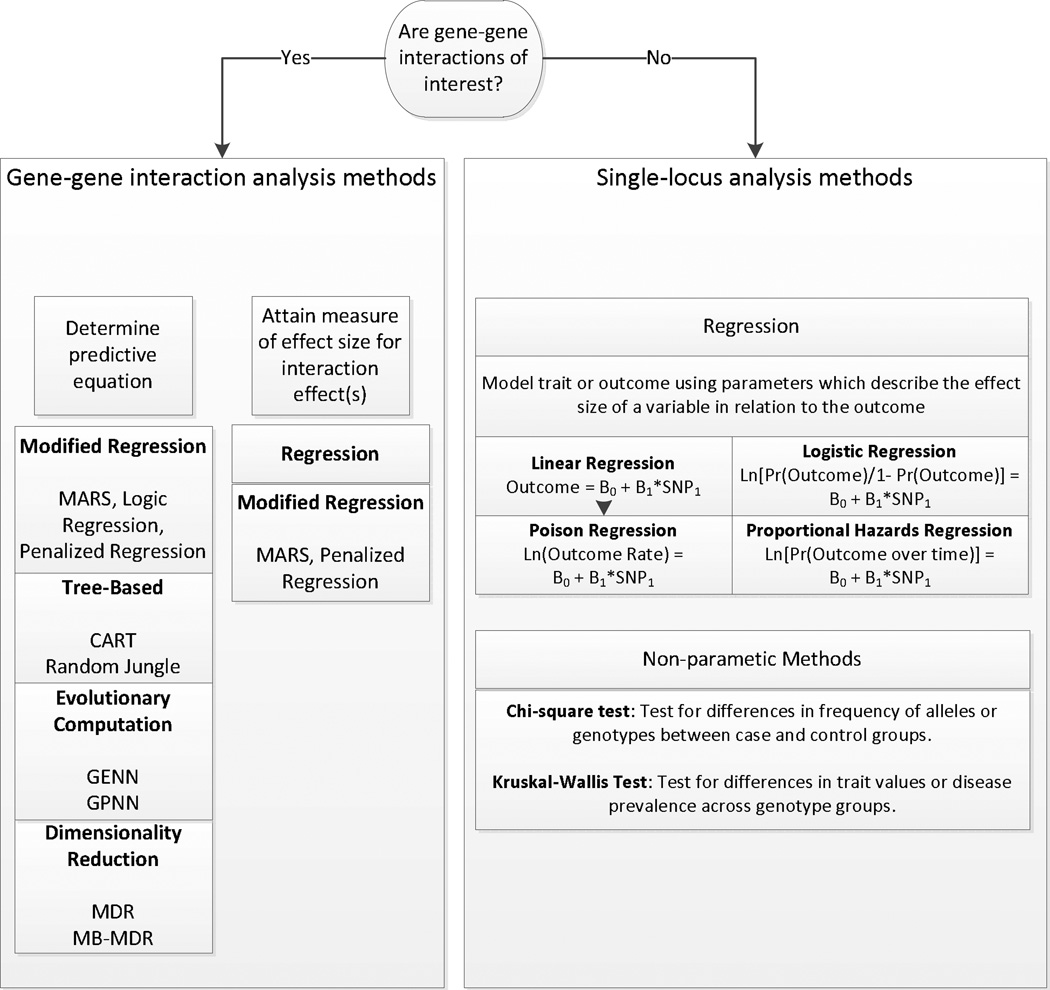

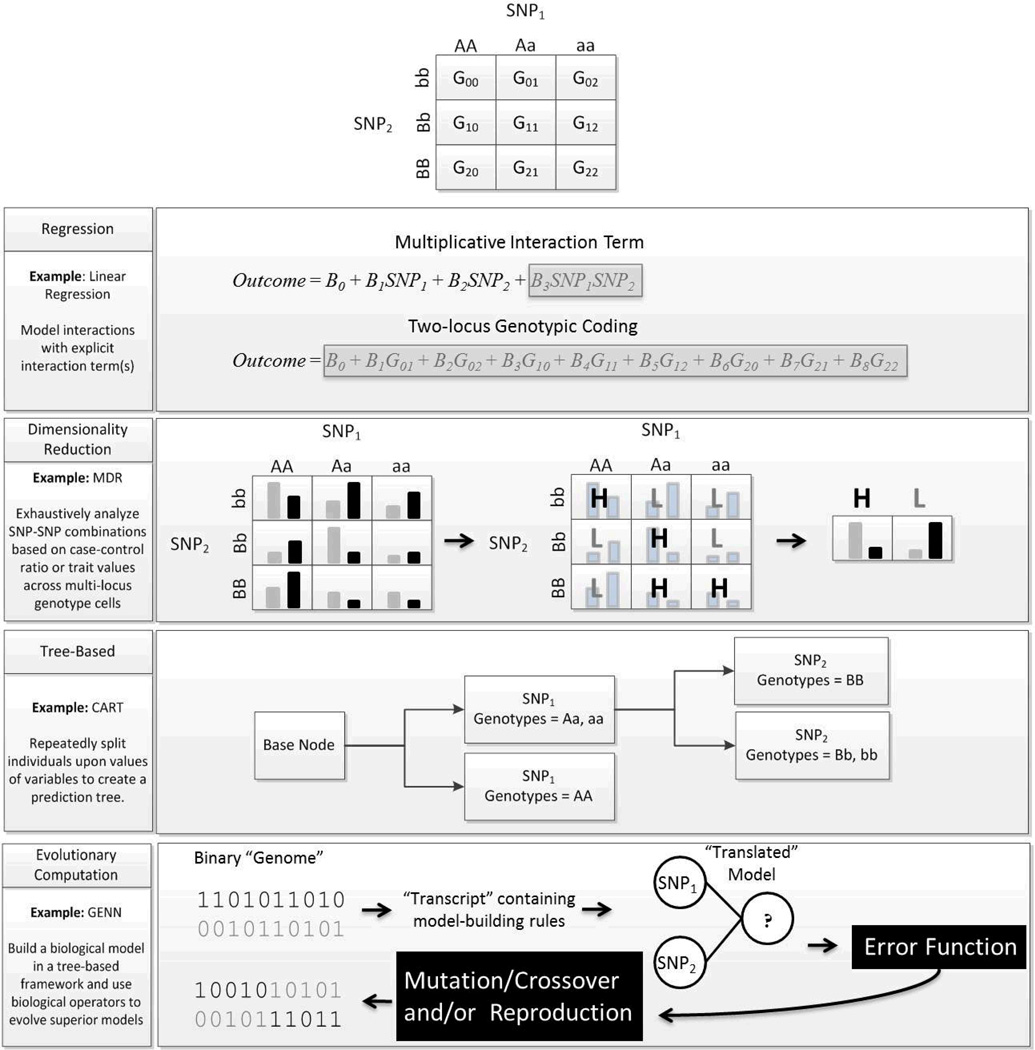

The answers to these questions should guide the analysis. As the study design varies according to the phenotype and the QC process varies according to the form of available genotype data, the analysis plan should be tailored around both of these factors. In this section, statistical tests for exploring monogenic associations, advanced methodology for identifying complex genetic effects, and methods for filtering the marker set will be discussed. Figure 4 demonstrates a simplified schematic for determining the statistical methodology which might be useful to employ during analysis.

Figure 4.

A flow chart of potential analysis designs to pursue based on the form of the study question.

7.1. Single SNP Analysis Methods

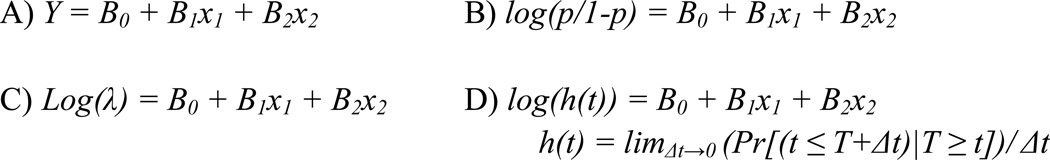

Analysis in pharmacogenomic association studies can utilize any of a large array of statistical methods [152] such as Chi-square test [153, 154], Armitage trend test [155, 156], Kaplan-Meier survival curves [157, 158], Bayesian statistics [159], or data mining methods [160] but is commonly performed in the framework of regression [161, 162, 163, 164]. This paper will focus primarily on the use of regression techniques for single-SNP analysis. The outcome under study dictates the type of regression to perform. Most forms of regression work off of the backbone of generalized linear models [165] but use different link functions. A link function merely describes the relationship between the dependent variable (i.e. the outcome) and the independent variable(s) (i.e. genetic markers or covariates). The link functions of the four commonly used types of regression - linear, logistic, Poisson and proportional hazards - are shown in Figure 5. For simplicity, examples given in this section of our paper refer to a regression equation testing the effect of a single genetic variant on the outcome with exception of the discussion of regression parameters and assumptions provided for linear regression.

Figure 5.

Regression equations used in genetic epidemiology. A) The identity link function for linear regression predicts the mean trait value, Y. B) The logit link for logistic regression predicts the odds, [p/(1-p)], of the outcome. C) Poisson regression uses the log function to predict the rate, λ, of events. D) Cox proportional hazards regression also uses the log function but predicts the hazard, h(t), at time t. Each regression function assumes an intercept B0 - the value of the mean, odds, rate or hazard when all independent variables are coded to 0 - and fits a coefficient Bn to describe the effect of each independent variable xn.

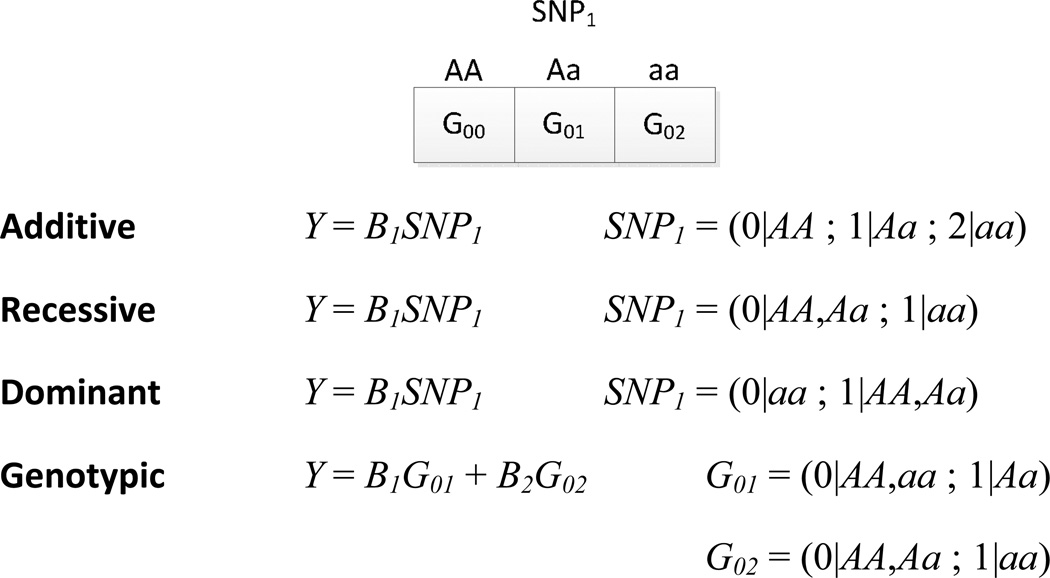

When the outcome is continuously distributed linear regression should be employed. Linear regression utilizes what is known as the identity link function - a linear relationship with no transformation of the outcome - to assess the effect of the variant on the mean outcome/trait value. The parameter provided by linear regression is an estimate of the mean difference in the continuous trait across groups differing by one genotypic level/unit [166]. A level with respect to the genotype will depend on the coding used in the regression equation. Different genotype coding schemes as applied to the framework of a regression equation are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Coding conventions for genetic markers with two alleles when performing regression.

Typically, an additive encoding is used to statistically test each SNP for association. Coding the three genotypes of a genetic variant with two alleles in an additive manner involves defining one genotype as the reference genotype and then establishing genotypes of intermediate and strong effect. The reference genotype is usually set to be the major allele homozygote and then the intermediate and strong effect genotypes are the heterozygote and minor allele homozygote, respectively. An additive coding assumes added risk of each additional variant allele and is utilized primarily because it yields the highest statistical power when the underlying genetic model is unknown. Although the additive encoding is most common, dominant, recessive or custom genotype encodings might be advantageous based on available knowledge of the genetic etiology. Each independent variable in the regression equation has a parameter which describes the size of its affect on the study outcome. For the estimates of the parameters associated with each independent variable to be valid in linear regression, there are distributional assumptions which must be met. These assumptions include homogeneity of variance of the residuals across groups defined by genotype or other variables, normality of the distribution of residuals, and independence of observations [166].

The term residual refers to the difference for each individual between the individual’s true outcome value and the value which is predicted by the linear regression equation. Homogeneity of variance and normality of the distribution of residuals requires that these residual errors follow a normal distribution overall and that the variation or spread of the residuals is roughly equivalent across each independent variable group (e.g., across each of the three genotype groups). Independence of observations describes the requirement that the outcome value for each study participant is uncorrelated with that of every other participant. The assumptions of any statistical method must be fulfilled for that method to provide accurate estimates of the effect size and associated p-value for the parameter of each independent variable. To protect from deviations in distributional and variance assumptions, some recommend the use of robust standard error estimates [167].