Abstract

The three-dimensional (3-D) architecture of rigid multiphase networks present in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 piston alloys in as-cast condition and after 4 h spheroidization treatment is characterized by synchrotron tomography in terms of the volume fraction of rigid phases, interconnectivity, contiguity and morphology. The architecture of both alloys consists of α-Al matrix and a rigid long-range 3-D network of Al7Cu4Ni, Al4Cu2Mg8Si7, Al2Cu, Al15Si2(FeMn)3 and AlSiFeNiCu aluminides and Si. The investigated architectural parameters of both alloys studied are correlated with room-temperature and high-temperature (300 °C) strengths as a function of solution treatment time. The AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys behave like metal matrix composites with 16 and 20 vol.% reinforcement, respectively. Both alloys have similar strengths in the as-cast condition, but the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 is able to retain ∼15% higher high temperature strength than the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy after more than 4 h of spheroidization treatment. This is due to the preservation of the 3-D interconnectivity and the morphology of the rigid network, which is governed by the higher degree of contiguity between aluminides and Si.

Keywords: Synchrotron radiation computed tomography, Cast aluminium alloys, Aluminides, Hot compression, Strengthening mechanism

1. Introduction

Eutectic cast Al–Si alloys are widely used for automotive components such as cylinder heads, pistons and valve lifters [1]. The gas temperature within a combustion chamber of a diesel engine can reach up to ∼300–400 °C with thermal cycles of ∼ΔT = 220 °C occurring in each combustion cycle. The temperature amplitude during start-up may reach 300 °C, and therefore high-temperature strength and thermal fatigue resistance are important requirements for the design of piston alloys [2].

The high-temperature strength of eutectic Al–Si alloys is given by a transfer of load from the ductile α-Al matrix to the rigid eutectic Si, a strengthening mechanism characteristic of fibre-reinforced composites [3]. The degree of reinforcement depends on the morphology, volume fraction and distribution of the eutectic Si, namely its architecture. The morphology of eutectic Si after casting is given by the mean temperature gradient in the melt during solidification and the growth rate of the solidification front [4]. Depending on this, eutectic Al–Si can solidify between the initially solidified α-dendrites in the form of a three-dimensional (3-D) interconnected network of Si platelets embedded in the ductile α-Al matrix, as revealed in the 1960s by deep etching [5] and verified recently by focused ion beam-energy dispersive spectroscopy [6]. These interconnected architectures of eutectic Si increase the strength of eutectic Al–Si alloys due to an extra load transfer from the α-Al matrix to the 3-D network of Si lamellae [7]. If Al–Si alloys are solution treated above 500 °C, the eutectic Si disintegrates and spheroidizes, converting the alloy into a particle-reinforced-like composite [8,9]. This spheroidization of the eutectic Si limits the use of AlSi12 cast alloys for high-temperature applications. The addition of transition elements such as Ni and Cu are considered to be an effective way to improve the high-temperature strength of cast Al–Si alloys in as-cast and solution-treated conditions by forming stable aluminides [10–15]. Recently, we have shown that the higher high-temperature strength exhibited by AlSi12Ni as compared to a Ni-free AlSi12 alloy is conferred by a highly interconnected 3-D structure formed by 20 vol.% of eutectic Si, Al9FeNi and Al15Si2(FeMn)3 aluminides [9]. Furthermore, the results in Ref. [9] showed that the disintegration of the eutectic Si, and to some extent of the aluminides, is responsible for the decrease in strength of AlSi12Ni alloy after spheroidization heat treatment. In a different study, the 3-D architecture formed by different types of primary aluminides and eutectic Si in an AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy in as-cast condition was carried out by synchrotron and light optical tomography combined with energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis (EDX) [16]. It was shown that the 3-D structure of aluminides, namely Al7Cu4Ni, Al15Si2(FeMn)3, Al2Cu and Al4Cu2Mg8Si7, and the eutectic Si, has a large degree of interconnectivity and contiguity. These results show that the visualization and characterization of the microstructure of cast Al–Si piston alloys is necessary since their mechanical behaviour strongly depends on the architecture formed by the different phases. However, two dimensional (2-D) microstructural characterization is insufficient to determine complex morphologies, volume fractions, distribution, contiguity and interconnectivity of phases in such heterogeneous materials, and therefore 3-D characterization methods are necessary. Laboratory X-ray computed tomography is a non-destructive technique that can reveal the 3-D architecture of different types of aluminides present in Al–Si alloys due to the usually large X-ray attenuation difference between the α-Al matrix and the aluminides, but it is insufficient to reveal the eutectic Si [17]. This drawback can be overcome by means of synchrotron tomography (sXCT) because the high lateral coherence of the beam produces the necessary phase contrast to reveal components with similar attenuation such as Al and Si [18]. Taking this into account, sXCT is used in this work to reveal and quantify the architecture formed by aluminides and eutectic Si in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 piston alloys as well as its evolution during spheroidization treatment. The results are used to interpret the high-temperature strength exhibited by both alloys.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The composition of the investigated AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 piston alloys is shown in Table 1. Both alloys were produced by Kolbenschmidt (Germany) by industrial gravity die casting. These alloys were investigated in the as-cast (AC) condition and after spheroidization treatments (ST) at 490 °C for 20 min, 1 h, 4 h and 24 h. All the samples in AC and ST conditions were artificially overaged at 300 °C for 2 h to stabilize the precipitation conditions prior to testing.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the alloys (in wt.%).

| Alloy | Si | Cu | Ni | Fe | Mg | Mn | P | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlSi10Cu5Ni1 | 10 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.003 | Bal. |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni2 | 10 | 5 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0056 | Bal. |

2.2. X-ray diffraction analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out to determine the phases present in the alloys. XRD was performed at room temperature (RT) for both alloys in AC and 24 h ST conditions on a Panalytical X’Pert PRO system (primary and secondary Soller slit of 0.04 rad and 200 mm diffractometer circle) using Cu Kα radiation and a X’Celerator detector with a Ni Kβ filter. The 2θ range was 15–135°. The scan length was ∼2.55° with 30 s measuring time per scan length giving ∼6000 calculated steps. Structural refinement was carried out by the Rietveld method using the TOPAS 4.2 package [19].

2.3. Synchrotron tomography

SXCT was carried out at the ID19 beamline at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France. An energy of 17.6 keV was used for the tomographic scans of the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions. The phase contrast mode was used to distinguish the eutectic Si from the Al matrix. For this, the radiographies were recorded by placing the detector at a distance of 39 mm behind the sample. The detector was a 2-D charge-coupled-device camera developed at ESRF [20]. 1500 projections were acquired using an effective pixel size of (0.3 μm)2 for 3-D reconstruction. The reconstructed sXCT volume has a final size of 2048 × 2048 × 2048 voxels, with a voxel size of (0.3 μm)3 and 32 bit colour depth. ImageJ [21] was used to convert the 32 bit images to 8 bit and for processing the volumes. Avizo 6.3 [22] was used for analyzing these volumes in terms of connectivity and morphology.

2.3.1. Phase segmentation

2.3.1.1. Segmentation of aluminides

The large contrast between aluminides and α-Al, owing to the different absorption coefficients, allows their confident segmentation by setting a global greyscale threshold. A minimum particle size of 27 voxels (0.73 μm3) was considered. The aluminides were segmented using three different threshold values to account for the resolution limit at their border. The quantitative analyses were done for the three volumes obtained and the results are expressed as their mean value with an error that corresponds to the standard deviation between the three segmentations.

2.3.1.2. Segmentation of Si

The segmentation of eutectic and primary Si becomes difficult due to the phase contrast at the interface of the aluminides that is, in general, darker than the Si, but can present greyscale values in the range of that obtained for Si.

A 2-D anisotropic diffusion filter [23] was used to reduce the noise in the images, while preserving the sharp edges of Si and phase contrast in the reconstructed slices of sXCT data. A global threshold was then applied to segment the darker phase contrast regions. The segmented phase contrast was then 3-D dilated to include adjacent regions with greyscale values in the range of Si and thus remove the phase contrast adjacent to the aluminides. The segmented phase contrast was pasted over the original volume, and, finally, the segmentation of eutectic Si was performed by setting out three different global threshold values. A minimum Si particle size of 500 voxels (13.5 μm3) was considered.

2.4. Compression tests

Compression tests were carried out at a strain rate of 10−3 s−1 using a Bähr-T805 high-speed quenching dilatometer equipped with a deformation rig able to reach forces of up to 25 kN. Compression specimens 5 mm in diameter and 10 mm long were deformed up to ∼0.5 true strain at RT and at 300 °C for both alloys in all conditions. Two tests were performed for each condition.

3. Results

3.1. 2-D microstructure

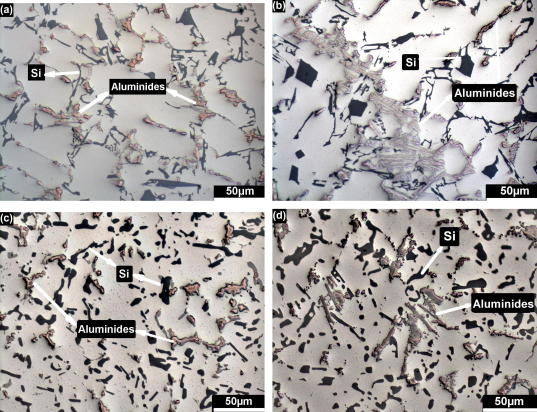

Fig. 1 shows light optical micrographs of the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions. Different types of aluminides with irregular shape, eutectic Si, primary Si and α-Al dendrites can be seen. Contiguity between all present phases can also be observed in the AC and 4 h ST conditions. Spheroidization of the eutectic Si, primary Si and aluminides after 4 h ST can be seen in Fig. 1c and d.

Fig. 1.

Optical micrographs of: (a) AlSi10Cu5Ni1, AC; (b) AlSi10Cu5Ni2, AC; (c) AlSi10Cu5Ni1, 4 h ST; (d) AlSi10Cu5Ni2, 4 h ST.

3.2. XRD analysis

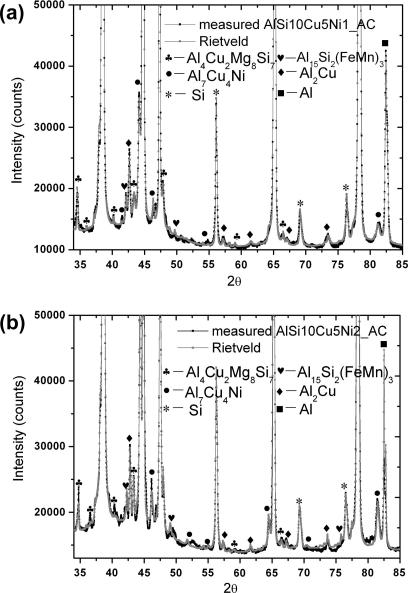

The AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys show similar XRD patterns in the AC and 24 h ST conditions, revealing that the same types of aluminides are present in both. These aluminides were indexed using Rietveld analysis as Al7Cu4Ni, Al2Cu, Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 and an Al–Si–Fe phase, presumably Al15Si2(FeMn)3. There remain unidentified low-intensity reflexes after the Rietveld refinement that represent <1 wt.% of unidentified phases in both alloys. An aluminide containing Al, Si, Fe, Ni and Cu was also identified by EDX analysis but no corresponding phase could be indexed by the Rietveld analysis. This phase may correspond to a modification of Al15Si2(FeMn)3 [31]. Fig. 2 shows a zoomed region of the XRD pattern of AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys with the identified phases in the AC condition.

Fig. 2.

X-ray diffraction pattern showing zoomed region with reflections of minor phases in (a) AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and (b) AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC condition.

3.3. Synchrotron X-ray tomography

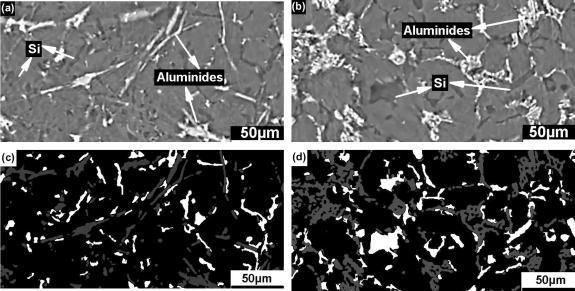

Fig. 3a and b shows cropped slices of 291 × 169 μm2 of AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in 4 h ST conditions obtained by sXCT. The different aluminides present in both alloys show similar contrast in the reconstructed tomographies and are considered together in the 3-D analysis. Volumes of 900 × 900 × 1500 voxels = 270 × 270 × 450 μm3 ≈ 0.03 mm3 were used for the quantitative 3-D analyses described in the following sections. Fig. 3c and d shows the same slices after segmentation of the aluminides (grey) and the Si (white). It can be seen that the procedure used to segment both phases is suitable for quantitative analysis.

Fig. 3.

Reconstructed synchrotron tomography slices of (a) AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and (b) AlSi10Cu5Ni2 4 h ST alloys (Si: dark; aluminides: bright); their respective segmentations are shown in (c) and (d).

3.3.1. Volume fraction of rigid phases

The volume fraction (Vf) of aluminides and eutectic + primary Si calculated from the sXCT volumes is shown in Table 2. The error in the volume fraction of aluminides and the eutectic + primary Si has been estimated using three different threshold values for the segmentation.

Table 2.

Quantitative tomography analysis in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC and ST condition represent.

| Alloys | Aluminides |

Eutectic + primary Si |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vf (%) | N (mm−3) | Vf (%) | N (mm−3) | |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni1-AC | 8 ± 1 | 6.3 × 104 | 9 ± 1 | 1.1 × 105 |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni1-4 h ST | 8.5 ± 1 | 9.0 × 105 (+1300%) | 10 ± 1 | 2.8 × 105 (+150%) |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni2-AC | 13 ± 1 | 7.3 × 104 | 11 ± 2 | 2.0 × 105 |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni2-4 h ST | 13 ± 1 | 6.4 × 105 (+750%) | 11 ± 1 | 2.1 × 105 |

The primary Si was found to be interconnected with eutectic Si in both alloys. Its volume fraction was calculated after disconnecting the blocky particles manually from the eutectic Si in the tomographies of the both samples. The volume fraction of primary Si in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys is ∼1.8 and ∼3.6 vol.%, respectively.

The total volume fraction of aluminides in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys is ∼8 ± 1 and ∼13 ± 1 vol.%, respectively.

The XRD results show that the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys contain the same types of aluminides, but a larger volume fraction of Al7Cu4Ni and AlSiFeNiCu aluminides is present in the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy due to the higher content of Ni.

Table 2 also indicates the number of particles per mm3, N, of eutectic + primary Si and aluminides in both alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions. The AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy shows a larger increase in N than for the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys after 4 h ST. This increase of N in both phases is due to the disintegration and coarsening of eutectic Si and aluminides during ST. The increase in N is larger for the aluminides than for the eutectic Si (Table 2).

3.3.2. Interconnectivity

The interconnectivity is defined in this work as the relative volume fraction of the largest particle of one phase with respect to the total volume fraction of that phase in the analyzed volume. Particle is understood here as an individual continuous 3-D region of a certain phase. The largest particle of a certain phase is therefore the largest of these 3-D regions that is found for the phase considered in the investigated volume. Table 3 indicates the relative volume fraction of the largest Si particle (column 2), of the largest aluminide particle (column 3) and of the largest particle formed by the combination of Si and aluminides (column 4) for both alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions in the volumes investigated (270 × 270 × 450 μm3). The numbers between brackets in Table 3 indicate the absolute volume fraction of these largest particles. There is no significant difference in the relative volume fraction of the largest Si and the largest aluminide particle between the AC and ST conditions in AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys.

Table 3.

Relative volumes of the largest interconnected structures and contiguity area of Si and aluminide particles of both alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions.

| Alloys | Largest Si particle (%) | Largest aluminide particle (%) | Largest combined particle of Si + aluminides (%) | Contiguity area 104 (μm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlSi10Cu5Ni1-AC | 85 ± 5 (7.65 ± 0.45 vol.%) | 95 ± 1 (7.6 ± 0.08 vol.%) | ∼97 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni1-4 h | 40 ± 10 (4 ± 1 vol.%) | 75 ± 2 (6.38 ± 0.17 vol.%) | ∼88 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni2-AC | 84 ± 5 (9.24 ± 0.55 vol.%) | 97 ± 1 (12.60 ± 0.13 vol.%) | ∼97 | 5.9 ± 0.8 |

| AlSi10Cu5Ni2-4 h | 80 ± 5 (8.8 ± 0.55 vol.%) | 94 ± 1 (12.20 ± 0.13 vol.%) | ∼97 | 6.6 ± 1.0 |

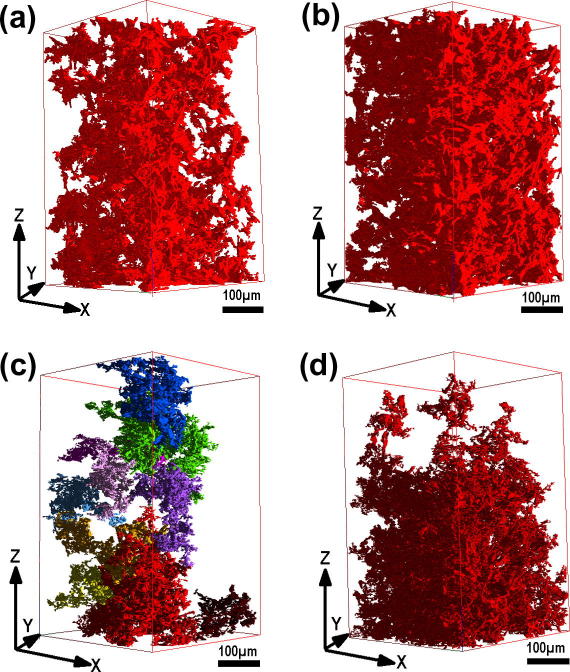

On the other hand, the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy shows a decrease in the relative volume fraction of the largest aluminide particle and of the largest Si particle, but this decrease is more pronounced for Si, dropping from ∼85% in AC to ∼40% after 4 h ST. This and the larger N increase for Si (Table 2) indicate that the disintegration of eutectic Si during ST is larger in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy than in the alloy with ∼2.5 times higher Ni content. Fig. 4 shows 3-D rendered volumes of the largest particles of aluminides and of the largest particles of Si in both alloys after 4 h ST. The different colours1 in Fig. 4c indicate the largest particles of Si within the analyzed volume. The largest particle formed by the combination of Si and aluminides (column 4 in Table 3) shows a decrease of ∼10% for AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy after 4 h ST, while it remains constant and practically fully interconnected for the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy. The largest particle of Si, the largest particle of aluminides and the largest combined particle formed by aluminides and Si in AlSi10Cu5Ni2 represent at least 80% of the corresponding total volume fraction of these phases. The largest Si particle in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy decreases from 85% to 40% of the Si volume fraction after 4 h solution treatment. This decrease in the measured level of interconnectivity of the Si phase after heat treatment is likely to be a result of spheroidization of the Si, in turn causing a decrease in the level of load transfer from the matrix to the Si phase, similar to the decrease in load transfer that comes with a reduction in the aspect ratio of discontinuous fiber reinforcements in composites [27].

Fig. 4.

Rendered structures of aluminides in (a) AlSi10Cu5Ni1, 4 h ST; (b) AlSi10Cu5Ni2, 4 h ST; and Si in (c) AlSi10Cu5Ni1, 4 h ST; (d) AlSi10Cu5Ni2, 4 h ST in a volume of ∼270 × 270 × 450 μm3 obtained by synchrotron tomography.

3.3.3. Contiguity

Contiguity between two phases is understood in this work as the interface area shared by them. The contiguity between aluminides and Si was computed in the following way after segmentation of each of these phases:

-

(a)

Three different grey values were assigned correspondingly to the aluminides, the Si and the matrix.

-

(b)

A self-developed algorithm was implemented to find the voxels at the surface of the aluminides which are connected to (touching) the voxels of the Si phase.

-

(c)

The interfacial area between Si and aluminides was then calculated by considering the number of common voxels sides which are shared by both phases and taking into account that the area of the side of a voxel is 0.3 × 0.3 μm2.

Table 3 indicates the total interfacial area between eutectic Si and aluminides in the analyzed volumes of both alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions. The contiguity area is similar in AC and ST conditions of both alloys, indicating that contiguity between aluminides and eutectic Si is conserved during ST. The AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy shows larger contiguity between Si and aluminides as compared to the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy.

3.3.4. Morphology

The shape of the rigid phases has been characterized by the Gaussian curvature (K) and the mean curvature (H) [24,25]. The Gaussian curvature (K) is the product of the two principal curvatures:

| (1) |

where k1 and k2 are the minimum and the maximum curvatures of the curves resulting from the intersection between the surface and planes containing the normal, respectively.

The mean curvature (H) is the mean value of the principal curvatures:

| (2) |

The Gaussian and mean curvatures were determined using the software Avizo 6.3 [22]. First, a surface was created from the segmented volumes of the phase considered (aluminides or Si) using the same software. The resulting surface is a triangular approximation of the segmented volumes. The curvatures were then calculated considering two direct neighbours to a certain triangle of the surface and the initial curvature values were smoothed by averaging them four times with the curvature values of direct neighbour triangles.

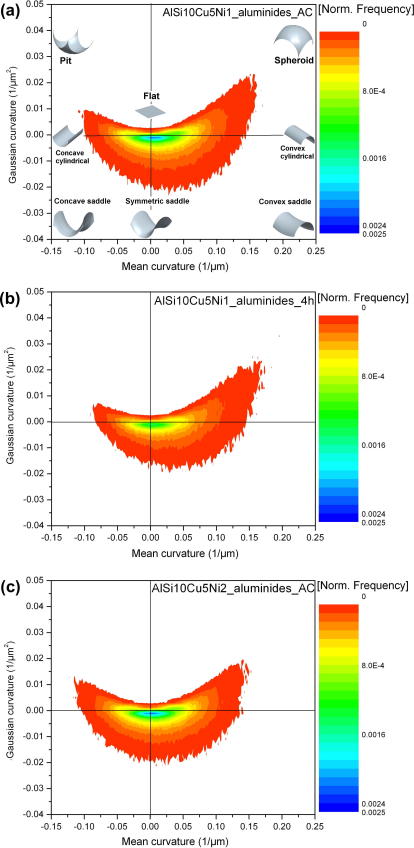

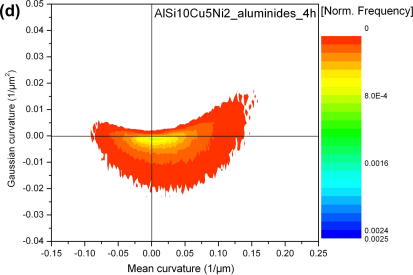

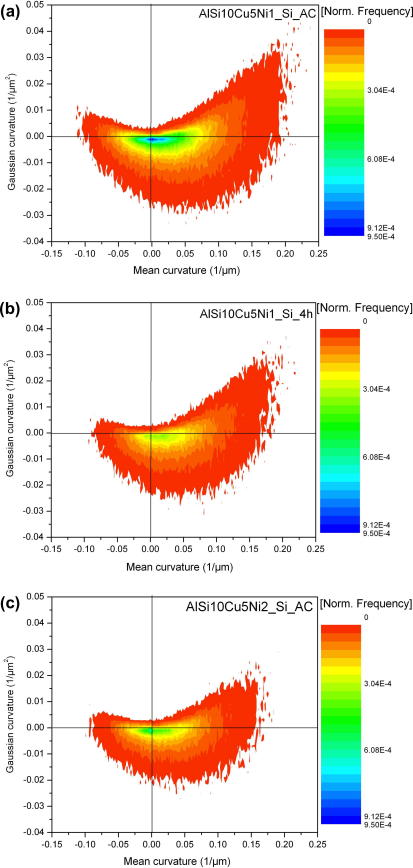

The sign of the Gaussian and mean curvature enables a morphological classification of aluminides and Si as described in Refs. [16,24]. The distributions of the Gaussian and mean curvatures of aluminides and of the eutectic Si calculated from the segmented sXCT tomography volumes are shown in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. The combined signs (positive or negative) of the Gaussian and mean curvatures result in different shapes, which are indicated on the quadrants and axes of Fig. 5a. The Gaussian curvature = mean curvatures = (0, 0) point corresponds to a flat surface. The aluminides in both alloys show a similar morphology distribution in the AC condition as shown in Fig. 5a and c for AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2, respectively. A maximum in the distributions can be found close to (0, 0) but still with slightly negative Gaussian curvature values, which indicates a rather flat symmetric saddle-like morphology. The curvatures distribution for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy show more surfaces with higher (positive/positive) values than the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy, indicating a higher fraction of spheroid-like regions with smaller radius. The maxima present close to the origin in Fig. 5a and c decrease their intensity after 4 h ST, indicating that flat surfaces, i.e. platelet-like regions, transform during the heat treatment. A decrease in the frequency of regions with high (negative/positive) curvatures is also observed for both alloys after 4 h ST. This corresponds to a decrease in the number of pit-like regions with smaller curvature radius. On the other hand, there is an increase in the number of regions with spheroidal shape for the aluminides of both alloys after 4 h ST, which is more marked for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy (see Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Mean and Gaussian curvatures of aluminides in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions.

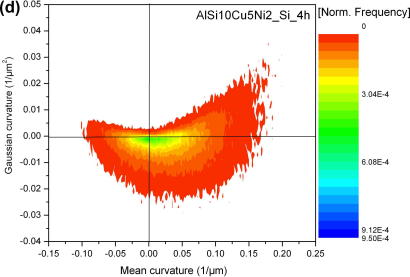

Fig. 6.

Mean and Gaussian curvatures of Si in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC and 4 h ST conditions.

The Si in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 AC alloy shows a similar maximum close to (0, 0), as is observed for the aluminides, which also decreases its intensity after 4 h ST. There is also a decrease in the number of regions with negative Gaussian curvatures (concave shapes) for the Si in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy after 4 h ST. On the other side, the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy does not show the marked peak close to zero for the Si and no significant changes are found in the distribution of curvatures for Si between AC and 4 h ST (Fig. 6c and d).

3.4. Compression tests

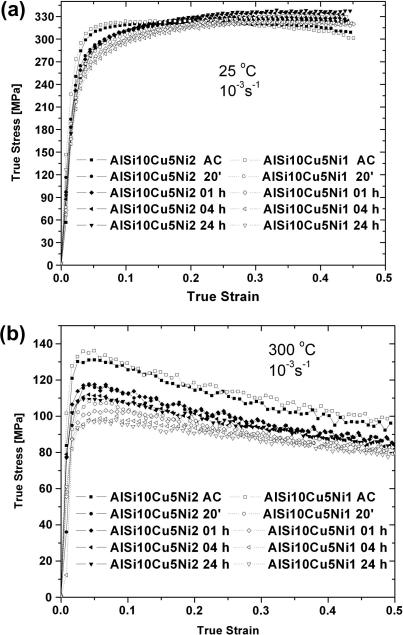

Characteristic true-stress vs. true-strain curves obtained during the compression tests at RT and 300 °C are shown in Fig. 7a and b for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys, respectively. Fig. 7a shows a typical strain-hardening behaviour in the ST conditions of both alloys at RT. On the other hand, Fig. 7b shows a typical strain-softening behaviour in all conditions of both types of alloys at 300 °C, indicating that damage is taking place during deformation.

Fig. 7.

True-stress vs. true-strain curves obtained during compression tests for AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys at (a) room temperature and (b) 300 °C.

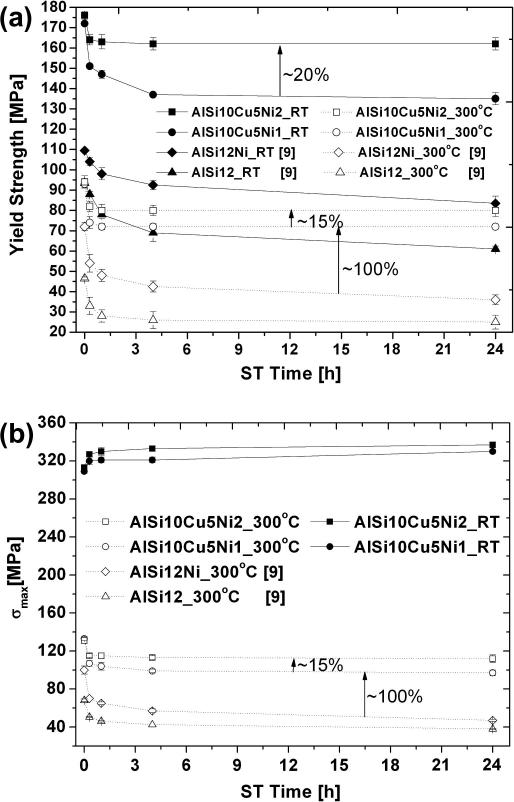

Fig. 8a shows the proof stress, σ0.2, at RT and at 300 °C as a function of the spheroidization treatment time for AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2. Results obtained in Ref. [9] for AlSi12 and AlSi12Ni are shown for comparison. Both alloys exhibit similar σ0.2 in AC condition, namely ∼175 MPa and ∼95 MPa at RT and at 300 °C, respectively. σ0.2 decreases with ST time, the largest decrease being observed during the first 20 min of the heat treatment. A stabilized condition is reached for σ0.2 between 1 and 4 h ST. The decrease in strength during the spheroidization treatment is more significant for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy than for the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy, resulting in a σ0.2 difference of about 20% and 15% at RT and 300 °C, respectively, after stabilization has been reached.

Fig. 8.

(a) Compressive yield strength and (b) maximum strength at room temperature and 300 °C for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys in AC and ST conditions.

Fig. 8b shows the dependence of σmax at RT and at 300 °C on ST time for both alloys. The AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys show similar trends of σmax. At RT, σmax increases with ST from ∼310 to ∼330 MPa in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy and to ∼340 MPa in the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy. At 300 °C, σmax decreases with ST from 135 to ∼100 MPa in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and to ∼110 MPa in AlSi10Cu5Ni2. The decrease in σmax with ST is ∼30% in AlSi10Cu5Ni1, while it is only ∼15% in AlSi10Cu5Ni2. Consequently, AlSi10Cu5Ni2 shows 15% larger σmax than the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy after the stabilized condition at 300 °C has been reached.

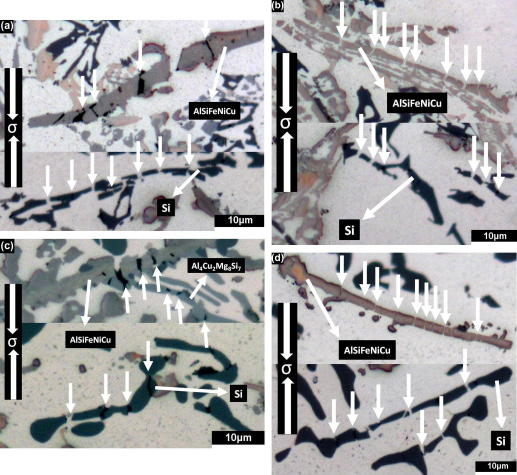

The occurrence of damage has been investigated in samples after deformation at RT and at high temperature. The same type of damage was observed at RT and at 300 °C with the only difference that more damage takes place at RT. Fig. 9a–d show characteristic light optical micrographs of cross-sections parallel to the compression axis for samples of AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 deformed at 300 °C in the AC and 4 h ST conditions, respectively. Microcracks (indicated by arrows) are mainly observed in Si, AlSiFeNiCu and Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 aluminides in both tested alloys. Debonding was observed neither between the Al matrix and the rigid phases nor between the rigid phases, revealing strong interfaces. Furthermore, damage in the Al matrix was not found in the investigated regions.

Fig. 9.

Optical micrographs of (a) AlSi10Cu5Ni1, AC; (b) AlSi10Cu5Ni2, AC; (c) AlSi10Cu5Ni1, 4 h ST; (d) AlSi10Cu5Ni2, 4 h ST samples compressed at 300 °C.

4. Discussion

The strengthening mechanisms responsible for the strength of the investigated AlSi10Cu5Ni1-2 alloys are:

-

(1)

The presence of strain-hardened regions built up in the Al matrix at the interface with the aluminides and the eutectic + primary Si. These regions are produced during cooling from the overaging heat-treatment temperature (300 °C) due to the thermal mismatch between the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTEs) of the matrix and the rigid phases. This effect is more pronounced at the interface with Si since the difference in CTE with the matrix is larger (∼20 × 10−6 K−1 [26]) than for the case between aluminides and matrix (∼10–12 × 10−6 K−1 [26]). This strengthening mechanism is characteristic of particle-reinforced metals [27].

-

(2)

Transfer of load from the Al matrix to rigid phases: this depends on the load-carrying capacity of these rigid phases, in this case the aluminides and the eutectic + primary Si, which is given by their volume fractions, mechanical properties, morphology, size and distribution. It was shown in Refs. [7,9] that large primary Si particles (>20 μm), with a polyhedral shape in the AC condition [28], do not contribute significantly to the high-temperature strength of eutectic AlSi alloys once these are rounded after spheroidization treatment. These primary Si particles amount ∼1.8 and ∼3.6 vol.% in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys, respectively. This results in an effective total volume fraction of phases with load-carrying capability of ∼16 and ∼20 vol.% in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys, respectively (see Table 2). The larger volume fraction of primary Si in AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy is due to the higher wt.% of P than in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy, which acts as nuclei for the formation of primary Si [29].

-

(3)

The degree of interconnectivity of the rigid phases: this can result in an extra increase of load transfer from matrix to the reinforcement which is more important at high temperatures where the matrix gets softer [30].

-

(4)

Solid-solution strengthening: the solubility of Cu in Al at RT is only ∼0.05 wt.% [31] and this does not have a strengthening effect at RT [32]. However, this effect must be considered at higher temperatures where the solubility of Cu in Al at 300 °C goes up to ∼0.45 wt.% [31]. The effect of Mg in solid solution can be neglected due to the surplus of atomic Si in the Al matrix that consumes the Mg to form Mg2Si precipitates. Cu and Mg are also bound by the formation of primary aluminides Al7Cu4Ni Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 and AlSiFeNiCu.

-

(5)

Precipitation hardening: precipitation strengthening due to Mg2Si, Al2CuMg and possibly Al2Cu will still play a role, although this will be minor because the alloys were always tested in an overaged condition (2 h/300 °C).

At high temperature (300 °C), mechanisms 2–4 play the most significant strengthening role. Mechanism 1 is not active at 300 °C because the strain-hardened regions will rapidly relax. In a recent study [9], the high-temperature strength of an AlSi12Ni1 alloy was investigated as a function of spheroidization treatment time and compared to an aluminide-free AlSi12 alloy. The results obtained for the σ0.2 and σm for these materials are shown in Fig. 8 together with those for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys. The higher strength shown by the AlSi12Ni1 alloy in comparison with the AlSi12 alloy was attributed to the larger volume fraction of rigid phases, the high interconnectivity of the aluminides and the high contiguity between aluminides and Si. The AlSi12Ni1 alloy has ∼8 vol.% aluminides [33], which is approximately the same as for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy (see Table 2). However, the aluminides in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy present a higher degree of interconnectivity (∼94% in AC condition and ∼75% after stabilization) with respect to the AlSi12Ni1 alloy (∼60% in AC condition and ∼50% after stabilization). The results in Fig. 8 show an increase of about 100% in σ0.2 and σm for the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy with respect to the AlSi12Ni1 alloy after stabilization. The strengthening due to the presence of Cu in solid solution at 300 °C can only result in an increase of strength of about 20% [32]. This means that the other 80% must be given by the combined effects of mechanical properties, morphology and interconnectivity of the rigid phases. This reveals that the main effect played by the addition of Cu to the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy with respect to the AlSi12Ni alloy is the formation of Al7Cu4Ni, Al2Cu, Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 and AlSiFeNiCu aluminides (see Fig. 2 and Ref. [34]) which result in an increase in the interconnectivity from 60% to 88% if the aluminides and Si are considered together. These aluminides plus their morphology and interconnectivity of the 3-D rigid structure result in a considerable (80%) increase in the high-temperature strength. The microcracks shown in the 2-D cross-sections of Fig. 9 are located in regions of the rigid 3-D structure in which the Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 and AlSiFeNiCu aluminides and eutectic Si present a short-fibre-like 2-D morphology with orientations ∼±30° perpendicular to the load axis. These regions are expected to carry an important portion of load and this is supported by the fact that the microcracks are, in general, oriented perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the rigid phases, i.e. within ∼±30° of the load axis similar to the case of short-fibre reinforced metal matrix composites [35,36].

The spheroidization treatment results in a decrease in the high-temperature strength for both investigated alloys, which stabilizes after 1 h at 490 °C. This decrease in strength and subsequent stabilization can be understood by taking into account the change in morphology (Figs. 6 and 7) and interconnectivity (Table 2) of the rigid phases during ST. In the AC condition, both the eutectic Si and the aluminides have a larger amount of regions with a platelet-like morphology than after 4 h ST. On the other hand, the solution treatment provokes the partial spheroidization of aluminides in both alloys, as reflected by the larger fraction of spheroid-like regions after 4 h ST. This effect is also observed for Si in the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy. Platelet-like regions are capable of bearing a higher portion of load transferred from the matrix than spheroid-like regions [7,9], and this is one of the reasons for the decrease in strength with ST time. Furthermore, the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy shows a higher strength than the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 after stabilization (1 h ST). The reason for this is the conservation of interconnectivity and the lower spheroidization of rigid phases (see Table 2 and Figs. 6 and 7). The preservation of interconnectivity in the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy is given by the higher contiguity between aluminides and Si, which is promoted by a larger volume fraction of aluminides in comparison to AlSi10Cu5Ni1 [37].

5. Conclusions

The RT and high-temperature strength of cast AlSi10Cu5Ni1 and AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloys has been investigated as a function of spheroidization treatment times and the results were correlated with their internal 3-D architecture. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

•

The formation of Cu-containing aluminides Al2Cu, Al7Cu4Ni, Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 and AlSiFeNiCu results in the formation of a highly interconnected 3-D network of aluminides and Si.

-

•

An increase in Ni content from 1 to 2 wt.% results in a ∼15% higher high temperature strength of the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 with respect to the AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy after 4 h spheroidization treatment. Although in the AC condition both alloys show similar degrees of interconnectivity of the rigid phases (Si + aluminides), i.e. ∼94–97%, the addition of more than 1 wt.% Ni is necessary to avoid the partial disintegration of the 3-D network during spheroidization treatment.

-

•

The spheroidization treatment results in the transformation of platelet-like regions into spheroid-like regions in both alloys, but this transformation is more significant in AlSi10Cu5Ni1 than in AlSi10Cu5Ni2.

-

•

The preservation of interconnectivity as well as, upto some extent, of the morphology of the rigid phases during spheroidization treatment in the AlSi10Cu5Ni2 alloy with respect to AlSi10Cu5Ni1 alloy is given by the higher contiguity between aluminides and Si. This is promoted by the higher volume fraction of Al7Cu4Ni and AlSiFeNiCu aluminides.

Acknowledgements

Z. Asghar would like to thank the Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan, for providing financial support for his Ph.D. work. The authors acknowledge Kolbenschmidt, Germany for provision of the alloys, Prof. F. Kubel for performing XRD analysis and H.P. Degischer for stimulating discussions. The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) is also acknowledged for the provision of synchrotron radiation access at the ID19 beamline. The authors would like to thank the Austrian Science Fund for financial support (Project FWF P-22876-N22).

Footnotes

For interpretation of colour in Fig. 4, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

References

- 1.Davis J.R. ASM International; Metals Park, OH: 1993. ASM specialty handbook: aluminium and aluminium alloys. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantor B., O’ Reilly K. Institute of Physics; London: 2003. Solidification and casting. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahoo M., Smith R.W. Metal Sci. 1975;9:217. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day M.G., Hellawell A. Proc Roy Soc A. 1968;305:473. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell J.A., Winegard W.C. Nature. 1965;5006:177. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasagni F., Lasagni A., Marks E., Holzapfel C., Mücklich F., Degischer H.P. Acta Mater. 2007;55:3875. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Requena G., Garcés G., Rodrígues M., Pirling T., Cloetens P. Adv Eng Mater. 2009;11:1007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogris E., Wahlen A., Lüchinger H., Uggowitzer P.J. J Light Met. 2002;2:197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asghar Z., Requena G., Kubel F. Mater Sci Eng A. 2010;527:4691. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho Y.H., Im Y.R., Kwon S.W., Lee H.C. Mater Sci Forum. 2003;426–432:339. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohatgi P.K., Sharma R.C., Praphakar K.V. Metall Trans A. 1975;6:569. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hukai S., Takeuchi K., Tanaka E. J Soc Mater Sci Jpn. 1964;13:190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moustafa M.A., Samuel F.H., Doty H.W. J Mater Sci. 2003;38:4523. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ammar H.R., Moreau C., Samuel A.M., Samuel F.H., Doty H.W. Mater Sci Eng A. 2008;489:426. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yunguo Li., Yang Y., Wu Y., Wang L., Liu X. Mater Sci Eng A. 2010;527:7132. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asghar Z., Requena G., Boller E. Pract Metallogr. 2010;9:471. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kastner J., Harrer B., Requena G., Brunke O. NDT E Int. 2010;43:599. doi: 10.1016/j.ndteint.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baruchel J., Buffiere J.Y., Cloetens P., Michiel M.D., Ferrie E., Ludwig W. Scripta Mater. 2006;55:41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.TOPAS Version 4.2, Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany; 1999.

- 20.Labiche J.C., Mathon O., Pascarelli S., Newton M.A., Ferre G.G., Curfs C. Rev Sci Instrum. 2007;78:091301. doi: 10.1063/1.2783112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/.

- 22.http://www.vsg3d.com/.

- 23.http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/plugins/anisotropic-diffusion-2d.html.

- 24.Kuijpers N.C.W., Tirel J., Hanlon D.N., Zwaag S.V.R. Mater Charact. 2002;48:379. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohser J., Mücklich M. Wiley; New York: 2000. Statistical analysis of microstructures in materials science. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C.L., Thomson R.C. Intermetallics. 2010;18:1750. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hull D., Clyne T.W. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2003. An introduction to composite materials. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sing H., Gokhale A.M., Tewari A., Zhang S., Mao Y. Scripta Mater. 2009;61:441. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu L., Liu X., Ding H., Bian X. J Alloys Compd. 2007;432:156. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Requena G., Garcés G., Asghar Z., Marks E., Staron P., Cloetens P. Adv Eng Mater. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mondolfo L.F. Butterworth; London: 1979. Aluminium alloys: structure and properties. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kammer C. Aluminium taschenbuch. Düsseldorf. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asghar Z., Requena G., Degischer H.P., Cloetens P. Acta Mater. 2009;57:4125. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belov N.A., Eskin D.G., Avxentieva N.N. Acta Mater. 2005;53:4709. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dlouhy A., Eggeler G., Merk N. Acta Metall Mater. 1995;43:535. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Requena G., Garcés G., Danko S., Pirling T., Boller E. Acta Mater. 2009;57:3199. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uggowitzer P.J., Stuewe H.V. Int J Mat Res. 1982;73:277. [Google Scholar]