Abstract

Background:

Bile duct injury (BDI) is a severe complication that may arise during the surgical treatment of benign disease and a few patients will develop end-stage liver disease (ESLD) requiring a liver transplant (LT).

Objective:

Analyse the experience using LT as a definitive treatment of BDI in Argentina.

Patients and Methods:

A national survey regarding the experience of LT for BDI.

Results:

Sixteen out 18 centres reported a total of 19 patients. The percentage of LT for BDI from the total number of LT per period was: 1990–94 = 3.1%, 1995–99 = 1.6%, 2000–04 = 0.7% and 2005–09 = 0.2% (P < 0.001). The mean age was 45.7 ± 10.3 years (range 26–62) and 10 patients were female. The BDI occurred during cholecystectomy in 16 and 7 had vascular injuries. One patient presented with acute liver failure and the others with chronic ESLD. The median time between BDI and LT was 71 months (range 0.2–157). The mean follow-up was 8.3 years (10 months to 16.4 years). Survival at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years was 73%, 68%, 68% and 45%, respectively.

Conclusions:

The use of LT for the treatment of BDI declined over the review period. LT plays a role in selected cases in patients with acute liver failure and ESLD.

Keywords: liver transplantation, cholecystectomy, bile duct injury

Introduction

Iatrogenic injuries of the bile duct can occur in any surgical procedure performed in the upper abdomen, but cholecystectomy remains the leading cause of these injuries.1–5 The delay in the correct diagnosis and the elapsed period between the time of a bile duct injury (BDI) and the time of referral, are factors that could influence negatively post-operative outcome.6–8

Moreover, the success of the repair in primary centres is significantly lower than in specialized ones,9–12 and two-thirds of patients with BDI that are reconstructed in the primary centre require later repeated interventions at referral centres.13

Successive failures of therapeutic procedures or the use of inappropriate treatments may determine the manifestation of late complications such as portal hypertension and secondary biliary cirrhosis (SBC).14–17 As a result of the development of such complications, a proportion of patients with complex lesions may require to be placed on the waiting list (WL) for a liver transplant (LT) as the only possible treatment.1,14–16,18–20

There are few publications regarding the role of LT in the management of BDI. Only a few reports have focused on the specific indication for patients presenting with acute liver failure (ALF) as a result of an associated vascular lesion,21–24 and case series reporting LT for patients with liver cirrhosis after BDI are scarce in the literature.1,3,14–16,18,25,26 This Argentinean study represents the first case series reporting national data for the application of LT as a treatment of iatrogenic BDI.

Materials and methods

In November 2009, a retrospective multicentre national survey of the 18 LT centres in Argentina was performed to collect clinical data on patients referred for transplantation as a consequence of iatrogenic BDI.

Analysed data included age, gender, type of initial surgery, mechanism and type of biliary lesion (according to Strasberg's classification7), time of diagnosis, surgical procedures performed before LT, indication of LT, time on the WL, status on WL, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score at the time of LT, transplant features and subsequent evolution.

Post-operative complications were classified according to Dindo et al.27 and major complications were defined as grade three to five. The pre-transplant assessment, indications of enlistment and the priority on the list were determined in accordance with regulations of the Unique Central National Institute of Ablation and Implant Coordinator (INCUCAI). Data from authorized LT centres and the number of transplants performed in Argentina during the period under study were obtained from official statistics.28

Categorical variables were expressed as a percentage whereas continuous variables with mean ± standard deviation (SD) [range (r)]. The χ2-test was used to compare proportions and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

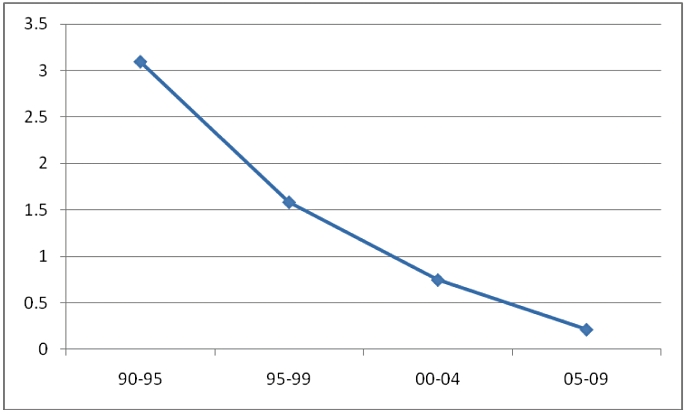

Out of 18 centres performing adult LT in Argentina, 16 responded to the survey reporting a total of 19 LT secondary to BDI. During the same period, 2766 adult LT were performed in Argentina. The percentage of LT by BDI of total LT per period was 3.1% between 1990 and 1994, 1.6% from 1995 to 1999, 0.7% between 2000 and 2004 and 0.2% for the period 2005–2009 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of liver transplant (LT) by bile duct injury (BDI) of total LT per period

Ten out of 19 transplant patients were female with a mean age of 45.7 ± 10.3 years (r 26–62). The surgery during which BDI occurred included: cholecystectomy in 16 cases (open in 10 and laparoscopic in 6), hydatid cyst resection in 2 and right hepatectomy in 1. The most frequent mechanisms of injury were bile duct division (7 cases) and duct resection (5 cases). The right hepatic artery (HA) was injured in 5 cases, whereas in 2 patients the right portal vein (PV) was also damaged.

According to the Strasberg classification, lesions included E2 in 4 patients, E3 in 10 patients and E4 in 3 patients. This classification was not applied for two patients because one presented with complete stenosis of the biliary duct owing to formaldehyde injection, and the other presented with a lesion in the left hepatic duct that occurred during a right hepatectomy. In six cases, the lesion was identified during surgery and was repaired immediately. In eight cases, it was detected during the first post-operative week and was repaired at the primary centre. In the remaining five patients, the injury was detected in the late post-operative period (as a result of alteration of liver enzymes and cholangitis). All but two patients had undergone previous surgical procedures at the primary centre before referral with a mean number of procedures of 2 (r 0–4).

The indication for LT was the presence of ALF in 1 case and liver cirrhosis in the remaining 18. Thirteen patients were shown to have esophageal varices on endoscopy (with repeated episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding in 9), 14 experienced recurrent episodes of cholangitis (with hepatic abscess in 2 patients) and 8 presented with intractable pruritus. The mean MELD score was 19 ± 8.6 (r 8–42). Patient characteristics before LT are expressed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics before liver transplant (LT)

| Patient | Gender | Age | Initial surgery | Previous biliary procedures | Transplant indication | Time lesion-LT (months) | TB | DB | ALP | PT | Child | MELD score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 37 | OC | PBD | SBC w PH | 105 | 13.4 | 9 | 1250 | 55 | B | 20 |

| 2 | M | 59 | OC | (1) Bile duct resection + HJ (2) PBD + PD | SBC w PH | 48 | 5.8 | 4 | 630 | 60 | A | 14 |

| 3 | F | 55 | OC | 1) abdominal drainage + HJ (2) PBD | SBC w PH | 44.4 | 0.6 | 0.19 | 149 | 87 | A | 8 |

| 4 | F | 53 | OC | (1) HJ (2)PBD | SBC | 0.7 | 9.9 | 5.9 | 644 | 80 | B | 22 |

| 5 | M | 32 | OC | (1) HJ (2) PBD | SBC w PH | 132.4 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 22 | 80 | B | 17 |

| 6 | M | 52 | OC | (1) T-tube placement (2) HJ (3) PBD + metallic stent | SBC | 93.5 | 17.4 | 14.6 | 973 | 92 | A | 12 |

| 7 | M | 40 | OC | (1) HJ (2) PBD | SBC | 29 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 1000 | 65 | B | 13 |

| 8 | F | 54 | OC | (1) HJ (2) PBD (3) re-HJ | SBC w PH | 58.1 | 10.1 | 6 | 780 | 70 | B | 18 |

| 9 | M | 44 | OC | (1) HJ (2) percutaneous drainage of hepatic abscess (3) PBD | SBC w PH | 153 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 24 | 60 | B | 17 |

| 10 | M | 41 | OC | (1) T-tube (2)PBD | SBC w PH | 55.3 | 11.3 | 6 | 1035 | 50 | B | 18 |

| 11 | F | 62 | LC | (1) abdominal drainage (2) PBD (3) HJ | SBC w PH | 112.6 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 450 | 73 | B | 19 |

| 12 | M | 55 | LC | (1) T-tube replacement (2) HJ (3) PBD (4) several replacements due to haemobilia | SBC w PH | 157.4 | 33 | 22 | 299 | 90 | C | 24 |

| 13 | F | 40 | LC | HJ (2) PBD (3) PD with extraction of intrahepatic stones | SBC | 56.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1600 | 88 | A | 8 |

| 14 | F | 29 | RH | (1) HJ (2) PBD | SBC | 11.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 1100 | 72 | B | 21 |

| 15 | F | 26 | HC | – | SBC w PH | 24.9 | 6.5 | 5 | 1823 | 80 | B | 17 |

| 16 | F | 46 | HC | (1) HJ (2) re-HJ | SBC w PH | 59.3 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 1200 | 71 | A | 11 |

| 17 | M | 50 | LC | (1)T-tube (2)ERCP | SBC w PH | 66.6 | 37.8 | 30.7 | 196 | 30 | C | 35 |

| 18 | F | 40 | LC | – | ALF | 71 | 20 | 12 | 870 | 20 | - | 42 |

| 19 | F | 54 | LC | HJ | SBC w PH | 74.5 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 800 | 60 | C | 28 |

| Mean | 71.2 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 781 | 67 | 19 | ||||||

| Range | 0.17–154.4 | 0.6–37.8 | 0.19–30.7 | 22–1823 | 20–92 | 8–42 | ||||||

OC, open cholecystectomy; LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; RH, right hepatectomy; HC, hydatid cyst resection; PBD, percutaneous biliary drainage; HJ, hepaticojejunstomy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PD, percutaneous dilatation; SBC, secondary biliary cirrosis; PH, portal hipertensión; TB, total bilirubin; DB, direct bilirubin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PT, prothrombin time.

The mean time between lesional surgery and transplantation was 71 months (r 0.2–157) and the mean time on the WL was 28 months (r 0.1–104 months). The LT was undertaken with a full-size deceased donor graft in 18 cases and in one instance a right lobe from an ex vivo split was used. Mean cold ischaemia time and operative time were 439 ± 99 min (r 240–660) and 438 ± 156 min (r 240–760), respectively.

Intra-operative injuries included a diaphragmatic laceration and a bowel perforation; both after division of dense adhesions, and both were immediately treated. No intra-operative mortality occurred.

Mean intensive care unit and hospital stay were 7 (r 4–11) and 21 (r 7–39) days, respectively. There were no early complications related to the biliary anastomosis. The major post-operative complication rate was 52% including five instances of grade 3 and four of grade 5 complications.

Four patients died during the post-operative period. One patient died on post-operative day 7 as a result of bacterial pneumonia with no abnormality of the graft observed at autopsy. A second patient died on post-operative day 30 from sepsis with a normal functioning graft. The third patient died as a result of necrotizing pneumonia and massive gastrointestinal bleeding on post-operative day 24. The remaining patient died as a consequence of a myocardial infarction on post-operative day 15.

Four patients died in the late post-operative period. One patient developed stenosis of the hepaticojejunostomy and required a revisional anastomosis on the seventh post-operative month. During the surgical exposure of the hepatic pedicle, hepatic arterial thrombosis was evident. As all the remaining arterial blood supply was compromised, the patient developed ALF secondary to liver devascularization and required emergency transplantation. He died on day 4 because of rupture of a cerebral mycotic aneurysm. The second patient died on the 17th post-operative month owing to bronchial carcinoma with bone metastasis. The third patient died at 120 months because of an endometrial cancer and the fourth experienced sudden death 10 years after transplantation.

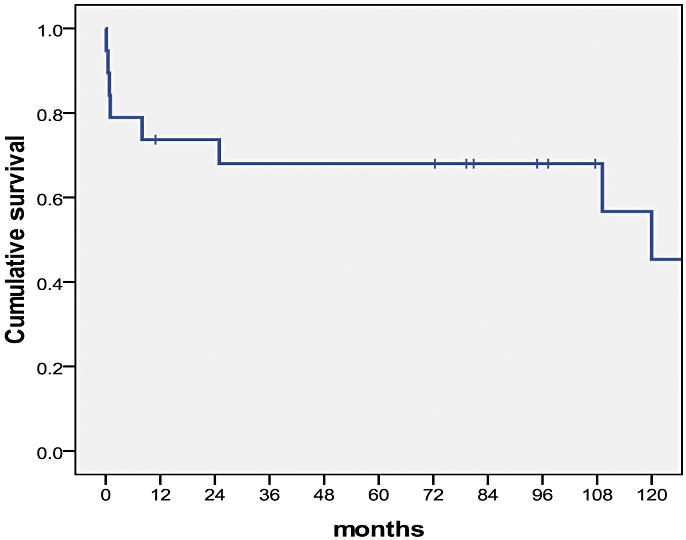

The remaining 11 patients reported a good quality of life on follow-up and liver function tests were within the normal range with a mean follow-up of 8.3 years (r 10 month to 16.4 years), survival at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years was 73%, 68%, 68% and 45%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Overall post-transplant survival

Discussion

We believe that this is the first report of a national survey on the use of LT in the treatment of iatrogenic BDI. In total and avoiding duplicate reporting, 45 patients (including this series) with LT for BDI in an acute and chronic setting are reported in the English literature (Table 2). While there are few case series reporting LT in the management of acute and chronic biliary lesions,1–3,14–16,18,21–25 progress in the safety of liver surgery and minimally invasive methods has led to this procedure being considered in the management of BDI.

Table 2.

Series reporting liver transplant (LT) as a consequence of bile duct injury (BDI)

| Author | Year | n | Type of surgery | Vascular injury | Cause of LT | Post-op mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacha et al.23 | 1994 | 1 | LC | 1 | FHF | No |

| Robertson et al.18 | 1998 | 1 | LC | 1 | SBC | No |

| Loinaz et al.3 | 2001 | 12 | 7 HCR, 4 OC, 1 RH | ? | SBC | 1/12 patients |

| Nordin et al.15 | 2002 | 5 | 4 LC, 1OC | 1 | SBC | 1/5 patients |

| Fernandez et al.21 | 2004 | 2 | LC | 2 | FHF | 2/ 2 patients |

| Öncel et al.25 | 2006 | 1 | OC | 0 | SBC | No |

| Thompson et al.26 | 2007 | 2 | OC | 1 | SBC | 1/ 2 patients |

| de Santibañes et al.1 | 2008 | 16 | 10 OC, 3 LC 1 RH, 2 HCR | 5 | SBC | 2/ 16 patients |

| Zaydfudim et al.2 | 2009 | 2 | 1 LC, 1 adrenalect. | 2 | FHF | no |

| McCormack et al.22 | 2009 | 1 | LC | 1 | FHF | 1/1 patient |

| Present series | 2010 | 19 | 10 OC, 6 LC 1 RH, 2 HCR | 7 | 18 SBC 1 FHF | 4/18 patients |

LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; OP, open cholecystectomy; RH, right hepatectomy; HCR, hydatid cyst resection; SBC, secondary biliar cirrhosis.

The impact on the use of LT for the management of these lesions has decreased significantly over the years and represented 3.1% of all LT in 1990–94 and 0.2% in 2005–09. We believe that this decline in the incidence reflects an improvement in the understanding of the pathology, leading to better prevention of injuries, more appropriate initial management of the lesions and a multidisciplinary and specialized approach of its complications.

Bile duct injuries are associated with increased peri-operative morbidity and mortality, a reduction in the quality of life and a decrease in long-term survival.29–31 Correct initial management of these lesions is essential for the prevention of acute and chronic complications or there is a risk of further darkening the prognosis of a generally young patient who has undergone surgery for a benign disease.

In these cases, LT is presented as an extreme treatment but is the best solution to offer a patient who is severely ill. In a previous study1 and in accordance with other reports,26 we noted a high mortality of patients on the WL for LT for acute or chronic complication of a BDI.

Morbidity and mortality in patients transplanted for complications of BDI appear to be greater than that reported for other aetiologies in Argentina28 and for SBC3. This reflects the greater technical complexity of the transplant usually as a result of multiple previous surgeries and deterioration that are often associated with septic complications.1,3,21,22,26 Refractory ascites, severe pruritus, recurrent cholangitis and intractable gastrointestinal bleeding are common conditions in these patients. Unfortunately, those symptoms did not influence the MELD score, leading to a longer time for these patients on the WL and a poor condition at the time of LT. Centres could request priority points for such conditions not included in the regulations, but the majority of these request are denied.32

However, there are two scenarios that require consideration. On the one hand, those patients who require LT for ALF secondary to ischaemia/necrosis of the liver as a result of associated vascular injury, and on the other hand, patients who develop SBC or recurrent cholangitis, because of a persistent biliary stricture with or without vascular injury. The occurrence of ALF because of portal triad injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a catastrophic but uncommon complication.2,21,24,33 Although isolated biliary or combined biliary and right HA transections can be managed either in the immediate post injury period or in a delayed fashion, injuries that also involve the PV cannot be treated expectantly.

In the absence of extensive hepatic infarction, sometimes the liver can be salvaged by treatment of the biliary lesion with associated vascular reconstruction.34

A hepatectomy may be an option when the necrosis is lobar but should be employed wisely because if the patient deteriorates after a partial hepatectomy owing to uncontrolled bleeding or post-operative infectious complication, the chance to be treated with delayed LT could be completely lost.35

In a patient with progressive coagulopathy secondary to multisystemic failure and poor condition, the indication of LT as a life-saving strategy could be considered.21,22,26

A recent study proposed that a total hepatectomy with portosystemic shunting and subsequent cadaveric LT could be a useful strategy for patients presenting with devastating portal transection recognized intra-operatively.2 Perhaps, this total hepatectomy performed within the first few hours could prevent the consequent multisystemic failure but this benefit is probably lost when diagnosis occurred late after surgery. Unfortunately, LT is rarely successful after iatrogenic combined vascular and biliary injury of the liver hilum, mainly because of septic complications.21,22,26 McCormack et al.22 suggest that the reduction in the immunosuppressive regimen could minimize post transplant septic complications, but there is still little evidence to support this.

The aim of repairing the BDI is the restoration of the bile duct and the prevention of complications in the short and long term such as a biliary fistula, an abdominal abscess, biliary stenosis, recurrent cholangitis and SBC. In many instances, the treatments in the primary centre fail leading to a sequence of reoperations and interventions. The delay in definitive treatment and the high number of interventions before referral to a specialist centre, increases patient morbidity and the possibility of remote sequelae.6,10,15

Concomitant arterial injury, regardless of the height of the biliary injury, may influence the evolution of primary repair attempts and may contribute to the development of ESLD.15,36,37 Schmidt et al. found that lesions above the bifurcation, repair in the presence of peritonitis and an associated right HA lesion were independent risk factors for the development of major biliary complications.14

Also, the development of biopsy proven liver fibrosis and SBC is associated with a delayed referral.38 Negi et al.39 found that the mean duration of biliary obstruction before the development of severe fibrosis is 22.4 months, and for cirrhosis 62 months.

Successive failures of therapeutic procedures or the use of inappropriate treatments may determine the manifestation of late complications such as portal hypertension and secondary biliary cirrhosis.14–17 Historical series show that nearly 10% of repairs resulted in liver cirrhosis and patients died of complications at a time when LT was not available.17 In recent series, 3–20% of the patients with complex lesions should be included on the WL for a LT as the only possible treatment.1,14–16

Liver transplantation is a controversial option for patients with chronic complex BDI; however, for patients with irreversible parenchymal damage as a result of SBC with chronic liver failure, it is the treatment of choice. Although LT in these patients provides long-term survival and a good quality of life, it represents a high biological price for the patient with an initial benign disease.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.de Santibañes E, Ardiles V, Gadano A, Palavecino M, Pekolj J, Ciardullo M. Liver transplantation: the last measure in the treatment of bile duct injuries. World J Surg. 2008;32:1714–1721. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaydfudim V, Wright JK, Pinson CW. Liver transplantation for iatrogenic porta hepatis transection. Am Surg. 2009;75:313–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loinaz C, González EM, Jiménez C, García I, Gómez R, González-Pinto I, et al. Long-term biliary complications after liver surgery leading to liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2001;25:1260–1263. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vicente E, Meneu JC, Hervás PL, Nuño J, Quijano Y, Devesa M, et al. Management of biliary duct confluence injuries produced by hepatic hydatidosis. World J Surg. 2001;25:1264–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang ZQ, Huang XQ. Changing patterns of traumatic bile duct injuries: a review of forty years experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:5–12. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, et al. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 2000;232:430–434. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Wit LT, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ. Surgical management of iatrogenic bile duct injury. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;230:89–94. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll BJ, Birth M, Phillips EH. Common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy that result in litigation. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:310–314. doi: 10.1007/s004649900660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart L, Way LW. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Factors that influence the results of treatment. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1123–1128. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430100101019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doctor N, Dooley JS, Dick R, Watkinson A, Rolles K, Davidson BR. Multidisciplinary approach to biliary complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1998;85:627–632. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topal B, Aerts R, Penninckx F. The outcome of major biliary tract injury with leakage in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:53–56. doi: 10.1007/s004649900897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirza DF, Narsimhan KL, Ferraz Neto BH, Mayer AD, McMaster P, Buckels JA. Bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: referral pattern and management. Br J Surg. 1997;84:786–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt SC, Langrehr JM, Hintze RE, Neuhaus P. Long-term results and risk factors influencing outcome of major bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:76–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordin A, Mäkisalo H, Isoniemi H, Halme L, Lindgren L, Höckerstedt K. Iatrogenic lesion at cholecystectomy resulting in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2499–2500. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Santibañes E, Palavecino M, Ardiles V, Pekolj J. Bile duct injuries: management of late complications. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1648–1653. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braasch JW, Bolton JS, Rossi RL. A technique of biliary tract reconstruction with complete follow-up in 44 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1981;194:635–638. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198111000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson AJ, Rela M, Karani J, Steger AC, Benjamin IS, Heaton ND. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy injury: an unusual indication for liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 1998;11:449–451. doi: 10.1007/s001470050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, McCormack L, Nefa J, Mattera J, Sívori J, et al. Liver transplantation for the sequelae of intra-operative bile duct injury. HPB (Oxford) 2002;4:111–115. doi: 10.1080/136518202760387993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman WC, Halevy A, Blumgart LH, Benjamin IS. Postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Management and outcome in 130 patients. Arch Surg. 1995;130:597–602. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430060035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández JA, Robles R, Marín C, Sánchez-Bueno F, Ramírez P, Parrilla P. Laparoscopic iatrogeny of the hepatic hilum as an indication for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:147–152. doi: 10.1002/lt.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormack L, Quiñones EG, Capitanich P, Chao S, Serafini V, Goldaracena N, et al. Acute liver failure due to concomitant arterial, portal and biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is trasplantation a valid life-saving strategy? A case report. Patient Saf Surg. 2009;3:22–26. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacha EA, Stieber AC, Galloway JR, Hunter JG. Non-biliary complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lancet. 1994;344:896–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madariaga JR, Dodson SF, Selby R, Todo S, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Corrective treatment and anatomic considerations for laparoscopic cholecystectomy injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oncel D, Ozden I, Bilge O, Tekant Y, Acarli K, Alper A, et al. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy requiring delayed liver transplantation: a case report and literature review. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:355–359. doi: 10.1620/tjem.209.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson BNJ, Parks RW, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ. Liver resection and transplantation in the management of iatrogenic biliary injury. World J Surg. 2007;31:2326–2369. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CRESI. Sistema Nacional de Información de Procuración y Trasplante de la Republica Argentina. Central de reportes y Estadísticas-CRESI. Available at https://cresi.incucai.gov.ar/Inicio.do.

- 29.Savader SJ, Lillemoe KD, Prescott CA, Winick AB, Venbrux AC, Lund GB, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomyrelated bile duct injuries: a health and financial disaster. Ann Surg. 1997;225:268–273. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moossa AR, Mayer AD, Stabile B. Iatrogenic injury to the bile duct. Who, how, where? Arch Surg. 1990;125:1028–1030. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410200092014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168–2173. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCormack L, Gadano A, Quiñonez E, Imventarza O, Andriani O, et al. Model for End Stage Liver Disease Exceptions Committee Activity in Argentina: does it provide justice and equity among adult patients waiting for a liver transplant. HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:531–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buell JF, Cronin DC, Funaki B, Koffron A, Yoshida A, Lo A, et al. Devastating and fatal complications associated with combined vascular and bile duct injuries during cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:703–708. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Frilling A, Nadalin S, Paul A, Malagò M, Broelsch CE. Management of concomitant hepatic artery injury in patients with iatrogenic major bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:460–465. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felekouras E, Megas T, Michail OP, Papaconstantinou I, Nikiteas N, Dimitroulis D, et al. Emergency liver resection for combined biliary and vascular injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2007;100:317–320. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000242793.15923.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta N, Solomon H, Fairchild R, Kaminski DL. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic artery injuries. Arch Surg. 1998;133:176–181. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koffron A, Ferrario M, Parsons W, Nemcek A, Saker M, Abecassis M. Failed primary management of iatrogenic biliary injury: incidence and significance of concomitant hepatic arterial disruption. Surgery. 2001;130:722–728. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson SR, Koehler A, Pennington LK, Hanto DW. Long-term results of surgical repair of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2000;128:668–677. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negi SS, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V, Chaudhary A. Factors predicting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:299–303. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]