Abstract

We have identified a mutant in RPB3, the third-largest subunit of yeast RNA polymerase II, that is defective in activator-dependent transcription, but not defective in activator-independent, basal transcription. The mutant contains two amino-acid substitutions, C92R and A159G, that are both required for pronounced defects in activator-dependent transcription. Synthetic enhancement of phenotypes of C92R and A159G, and of several other pairs of substitutions, is consistent with a functional relationship between residues 92–95 and 159–161. Homology modeling of RPB3 on the basis of the crystallographic structure of αNTD indicates that residues 92–95 and 159–162 are likely to be adjacent within the structure of RPB3. In addition, homology modeling indicates that the location of residues 159–162 within RPB3 corresponds to the location of an activation target within αNTD (the target of activating region 2 of catabolite activator protein, an activation target involved in a protein–protein interaction that facilitates isomerization of the RNA polymerase promoter closed complex to the RNA polymerase promoter open complex). The apparent finding of a conserved surface required for activation in eukaryotes and bacteria raises the possibility of conserved mechanisms of activation in eukaryotes and bacteria.

Keywords: RNA polymerase, transcription, activation, α subunit

Eukaryotic RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) acts in concert with a variety of gene-specific activators, repressors, and protein complexes during the regulated synthesis of mRNA (Greenblatt 1997; Myer and Young 1998). Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNAP II is the most extensively characterized eukaryotic RNAP II. It contains 12 subunits, designated RPB1–RPB12 in decreasing order of molecular mass (Young 1991; Sentenac et al. 1992). RPB1 and RPB2 are homologs of the bacterial RNAP β′ and β subunits, respectively, whose functions include template, nucleotide binding, and phosphodiester bond formation (Young 1991; Sentenac et al. 1992). RPB3 and RPB11 are homologs of the bacterial RNAP α subunit amino-terminal domain (αNTD; corresponding to the amino terminal two-thirds of the 329 amino acid α subunit; Young 1991; Sentenac et al. 1992; Ebright and Busby 1995; Zhang and Darst 1998). αNTD is present in two copies in bacterial RNAP and involved in RNAP assembly and transcriptional activation (Ebright and Busby 1995).

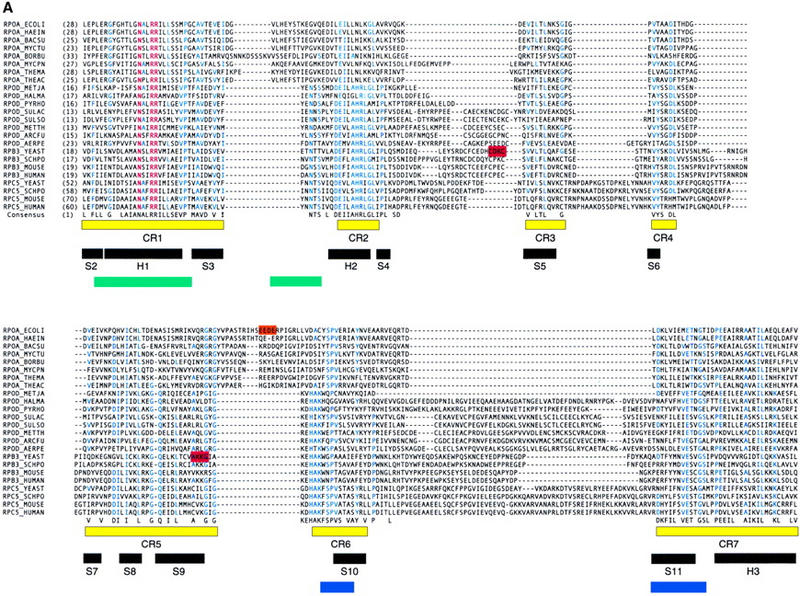

The 318 amino acid RPB3 subunit—and its counterparts in archaeal RNAP (RpoD) and eukaryotic RNAP I and RNAP III (RCP5; also known as AC40, RPA5)—exhibit amino acid sequence similarity to seven discrete conserved regions across the entire length of the αNTD (CR1–CR7; Fig. 1A; see also Zhang and Darst 1998). The 120 amino acid subunit RPB11—and its counterparts in archaeal RNAP (RpoL) and eukaryotic RNAP I and RNAP III (AC19; also known as RPC9)—exhibit amino acid sequence similarity to approximately one-half of αNTD, corresponding to CR1, CR6, and CR7 (Zhang and Darst 1998, and data not shown).

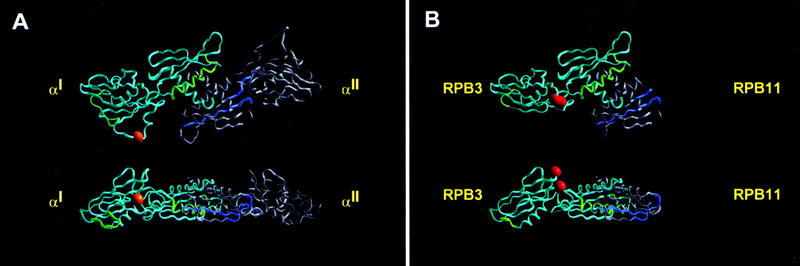

Figure 1.

Relationship between RPB3 and bacterial RNAP αNTD. (A) Aligned sequences of bacterial RNAP αNTD (RPOA_), archaeal RNAP RpoD (RPOD_), eukaryotic RNAP II RPB3 (RPB3_), and eukaryotic RNAP I and RNAP III RPC5 (RPC5_). Corresponding organism names are as follows: E. coli (ECOLI), H. influenzae (HAEIN), B. subtilis (BACSU), M. tuberculosis (MYCTU), B. burgdorferi (BORBU), M. pneumoniae (MYCPN), T. maritima (THEMA), T. aquaticus (THEAC), M. jannaschii (METJA), H. marismortui (HALMA), P. horikoshii (PYRHO), S. acidocaldarius (SULAC), S. solfataricus (SULSO), M. thermoautotrophicum (METTH), A. fulgidus (ARCFU), A. pernix (AERPE), S. cerevisiae (YEAST), S. pombe (SCHPO), M. musculus (MOUSE), H. sapiens (HUMAN). Residues invariant in the aligned sequences are in red; residues identical in at least half of the aligned sequences are in blue; residues identical or similar in at least half of the aligned sequences are listed in the consensus at bottom. CR1–CR7 (yellow bars) delineate conserved regions [defined as containing residues identical or similar in at least half of aligned sequences and in all three sets of aligned sequences (bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic) and containing no insertions or deletions greater than one residue]. CR1, CR2, CR6, and CR7, correspond, respectively, to region A, B, C, and D and E of Heyduk et al. (1996). α-Helices 1–3 and β-strands 2–11 in the crystallographic structure of E. coli αNTD (Zhang and Darst 1998) are indicated by black bars. Regions of bacterial RNAP that interact with the second-largest and largest subunits of RNAP are delineated by green and blue bars, respectively (Heyduk et al. 1996). Residues important for transcriptional activation in E. coli RNAP are highlighted in orange (Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999). Residues shown in this work to be important for transcription activation in S. cerevisiae RNAP II are highlighted in red. (B) Crystallographic structure of the E. coli RNAP αNTDI/αNTDII homodimer (two orthogonal views; Zhang and Darst 1998). αNTDI is defined as the protomer that interacts with the second-largest subunit of RNAP; αNTDII is defined as the protomer that interacts with the largest subunit of RNAP (Niu 1998; Zhang and Darst 1998; Estrem et al. 1999). CR1–CR7 are in yellow; nonconserved regions are in light blue. (C) Homology-modeled structure of the S. cerevisiae RPB3/RPB11 heterodimer (two orthogonal views). Conserved regions CR1–CR7 in RPB3 are in yellow; nonconserved regions in RPB3 are in light blue; RPB11 is in gray. Sites of deletions relative to the crystallographic structure of E. coli αNTD are indicated by thin lines; sites of insertions are indicated by blue spheres. RPB3 and RPB11 are assigned as corresponding to αNTDI and αNTDII, respectively, for the following reasons: First, the sequence N-X2-R-R in CR1—particularly the R at the fifth position within the sequence—is essential for interaction with the second-largest subunit of RNAP (Kolodziej and Young 1989, 1991; Kimura and Ishihama 1995a,b; Murakami et al. 1997; Niu 1998; Estrem et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 1999); this sequence is present in RPB3 but not in RPB11. Second, CR2 contains a secondary determinant for interaction with the second-largest subunit of RNAP (Heyduk et al. 1996; Zhang et al. 1999); CR2 is present in RPB3 but not in RPB11. Third, superimposition of the crystallographic structure of S. cerevisiae RNAP II at 6 Å resolution (as an electron density isocontour; Fu et al. 1999) on the crystallographic structure of T. aquaticus RNAP at 3.3 Å (Zhang et al. 1999) indicates that S. cerevisiae RNAP contains electron density corresponding to CR2–CR5 of αNTDI but not of αNTDII; CR2–CR5 are present in RPB3, but not in RPB11.

RPB3 and RPB11 heterodimerize both in solution (Ulmasov et al. 1996; Kimura et al. 1997; Larkin and Guilfoyle 1997; Fanciulli et al. 1998; Svetlov et al. 1998) and in the context of RNAP II (Kimura et al. 1997; Ishiguro et al. 1998). The structures of RPB3 and RPB11 can be homology-modeled on the basis of the crystallographic structure of αNTD (Fig. 1B,C; Zhang and Darst 1998). The RPB3/RPB11 heterodimer in RNAP II corresponds to the αNTDI/αNTDII homodimer in bacterial RNAP, in which αNTDI is the αNTD protomer that interacts with the second-largest subunit of RNAP (β) and αNTDII is the αNTD protomer that interacts with the largest subunit of RNAP (β′) (Fig. 1, B and C, and legend to C).

In this work we show that RPB3 contains two determinants specifically required for activator-dependent transcription—that is, required for activator-dependent transcription but not required for activator-independent basal transcription. In the homology-modeled structure of RPB3, the two determinants are located adjacent to each other and, strikingly, in a position that corresponds to the position of a characterized activation target within bacterial RNAP αNTDI.

Results and Discussion

rpb3-2, isolated in a screen for cold- and temperature-sensitive mutants in RPB3, has a severe defect in activator-dependent transcription in vitro

To learn more about the function of the essential RNAP II subunit RPB3, we analyzed the effects on transcription of extracts prepared from conditional mutants of RPB3. We performed random mutagenesis of the entire RPB3 gene using error-prone PCR, screened for mutants displaying cold- (12°C) and/or temperature-sensitive (37°C) phenotypes, and verified that conditional phenotypes resulted from mutations in RPB3. Eight cold-sensitive, 21 temperature-sensitive, and three cold- and temperature-sensitive mutants were isolated. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from RPB3 mutants with the tightest phenotypes and tested with an in vitro assay for basal transcription and GAL4–VP16-dependent activated transcription.

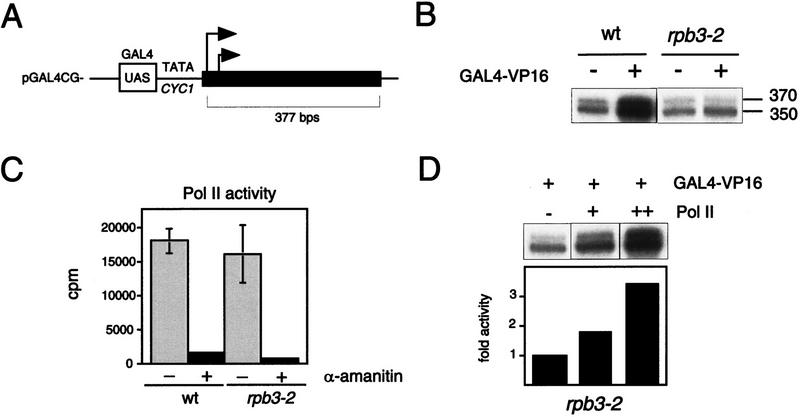

One mutant, designated rpb3-2, exhibited a temperature-sensitive, slow-growth phenotype (Fig. 2A,B) and a pronounced defect in GAL4–VP16-dependent transcription (Fig. 3B). The mutant was fully functional in basal transcription—both promoter-independent and promoter-dependent basal transcription (Fig. 3B,C)—but nearly completely defective in activation by GAL4–VP16 (Fig. 3B). Addition of purified RNAP II to mutant whole-cell extracts restored responsiveness to GAL4–VP16, indicating that RNAP II was the source of the activation defect in the mutant (Fig. 3D). We conclude that RPB3 contains determinants specifically required for GAL4–VP16-dependent transcription.

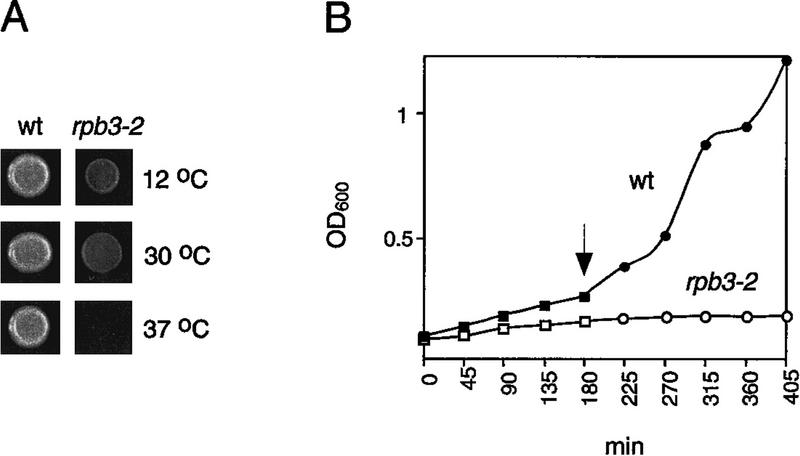

Figure 2.

(A) YPD plates were spotted with equal amounts of wild-type (wt) and isogenic mutant (rpb3-2) cells and incubated at the temperatures indicated. (B) Growth curves of the wild-type (█,●) and the isogenic rpb3-2 mutant strains (□,○) grown at the permissive (30°C) and nonpermissive temperatures (37°C, arrow designates time of temperature shift).

Figure 3.

In vitro transcription revealed an activation defect in rpb3-2 cell extracts. (A) DNA template used for transcription, arrows represent approximate transcription start sites within the 377-bp G-less cassette. (B) Transcription products from wild-type (wt) and mutant (rpb3-2) whole-cell extracts with (+) or without (−) added GAL4–VP16. mRNA sizes after gel electrophoresis and autoradiography are indicated. (C) rpb3-2 extracts have activity comparable with wild-type extracts in a nonselective transcription assay. Equivalent amounts of extracts were assayed for transcription from a denatured salmon sperm DNA template in the absence (−) or presence (+) of α-amanitin. Samples were tested in triplicate. (D) Addition of purified RNAP II fractions reconstitutes activation in mutant extracts.

RPB3-2 cells have severe defects in activator-dependent transcription in vivo

We used two approaches to assess the effects of the rpb3-2 mutant on activator-dependent transcription in vivo. First, we tested activator function by measuring expression levels of a lacZ reporter driven by an inducible promoter containing an upstream activation sequence (UAS). Second, we directly measured mRNA levels of inducible genes before and after activation.

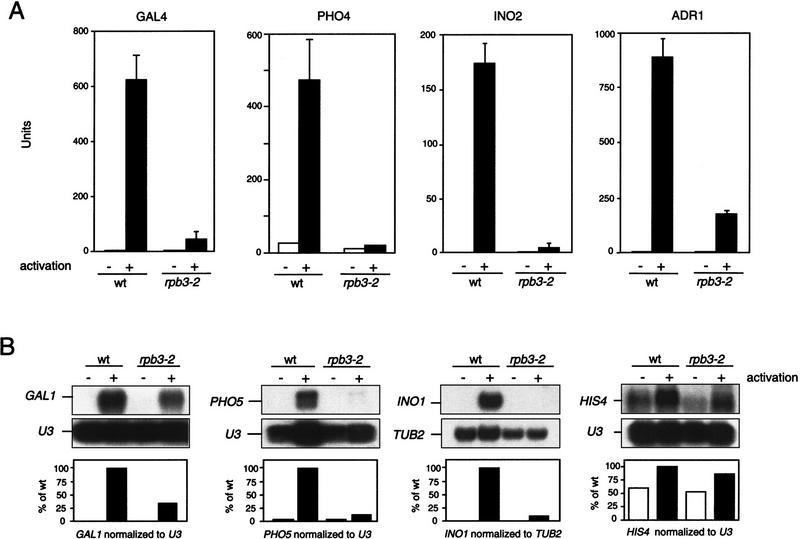

Wild-type and rpb3-2 cells containing reporter plasmids for measuring activation by GAL4, PHO4, INO2, and ADR1 were grown at the permissive temperature under nonactivating or activating conditions, and β-galactosidase activity was measured in extracts prepared from each strain. rpb3-2 cells were severely defective in activator-dependent transcription, both at the permissive (Fig. 4A) and nonpermissive temperatures (data not shown).

Figure 4.

rpb3-2 cells display activation defects for multiple inducible genes. (A) Impaired activation with four different activator reporter plasmids (activator shown above each graph). Assays were performed on extracts prepared from cells harvested after growth under activating (+) or nonactivating (−) conditions. Units represented as nanomoles o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactosidase cleaved per min per mg of protein. (B) Northern blot analysis of GAL1, PHO5, HIS4, and INO1 transcripts before (−) and after (+) activation. RNA was prepared from cells grown at the nonpermissive temperature (30°C). TUB2 (tubulin mRNA) and U3 (RNAP II transcribed snRNA) were included as loading controls. GAL1, PHO5, HIS4, or INO1 transcripts were normalized to their respective loading controls and graphed relative to the activated wild-type control.

Northern analysis also confirmed that rpb3-2 is defective in activator-dependent transcription at the INO1, GAL1, and PHO5 promoters (Fig. 4B, left three panels). (We were unable to measure ADH2 mRNA levels by this method, because two closely related transcripts, ADH1 and ADH3, cross hybridize to the ADH2 DNA probe.) Measurement of mRNA levels at the HIS4 promoter indicated that the mutant is not defective in activator-dependent transcription at this promoter (Fig. 4B, right).

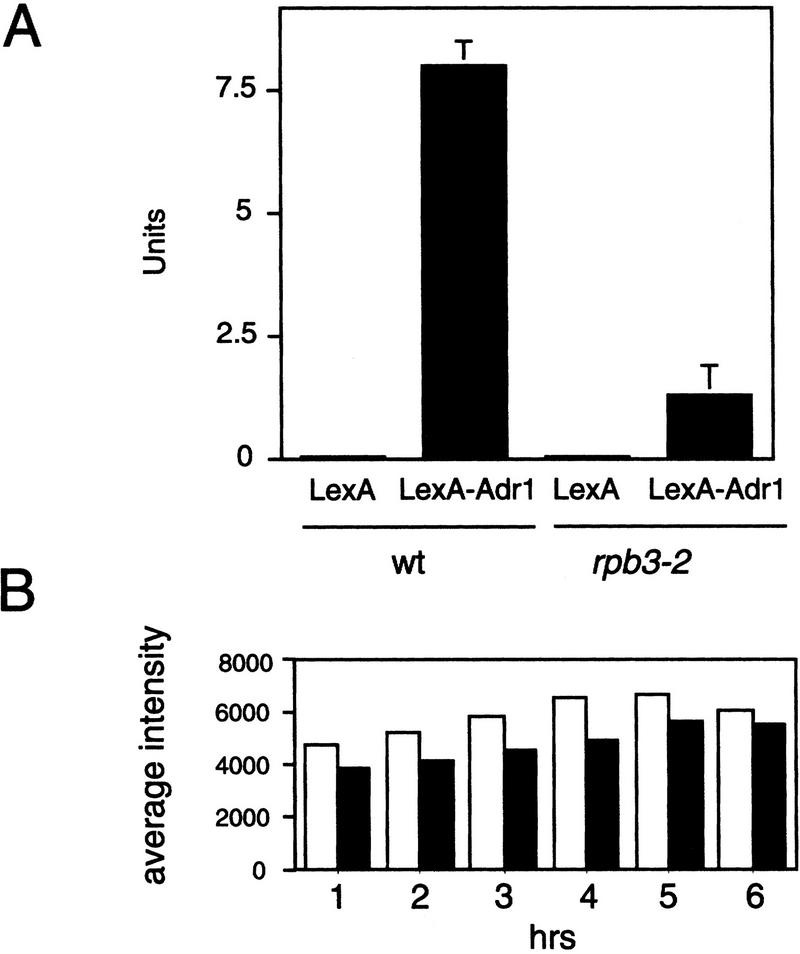

To address the possibility that the activation defects seen in the mutant might be a consequence of a defect in some other process, we tested whether rpb3-2 specifically affected activator function. We expressed the test activator LexA–Adr1 fusion protein from a plasmid in isogenic wild-type and mutant strains carrying a second plasmid containing the lexA operators fused to the lacZ reporter gene. The results support a role for RPB3 that is specific to the activation function of LexA–Adr1, as RPB3 mutant cells displayed a sixfold reduction in lacZ expression relative to wild type (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

The rpb3-2 mutant specifically affects the activation function of LexA–Adr1. (A) Cell samples (prepared from three independent transformants) were harvested from strains containing a lexA(op)–lacZ reporter plasmid plus a plasmid expressing either Adr1–LexA or the control LexA only and tested for β-galactosidase activity in duplicate. (B) Mutant and wild-type cells have comparable mRNA levels before and after the shift to nonpermissive temperature. Analysis of total mRNA levels of wild-type (wt) compared with mutant (rpb3-2) cells, before (0 hr) and after (1–6 hr) temperature shift to the nonpermissive temperature (37°C); (open bars) wild type, (solid bars) rpb3-2.

The rpb3-2 mutation does not cause a global effect on transcription in vivo, because total mRNA levels in rpb3-2 cells are 80%–90% of those in wild-type cells—both at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, mRNA levels of a variety of genes—ACT1, U3, TUB2, PDA1, DED1, HIS3, SUA7, SRB5, RPB1, and RPB3—in the RPB3 mutant are not significantly lower than those in wild-type cells at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures (data not shown). We conclude that the rpb3-2 mutant is defective in activator-dependent transcription in vivo, that the defect is severe, and that the defect is pleotropic (affecting GAL1, PHO5, INO1, and ADH2) but not universal (not affecting HIS4).

rpb3-2 has two mutations that are both required for maximal impairment of activation

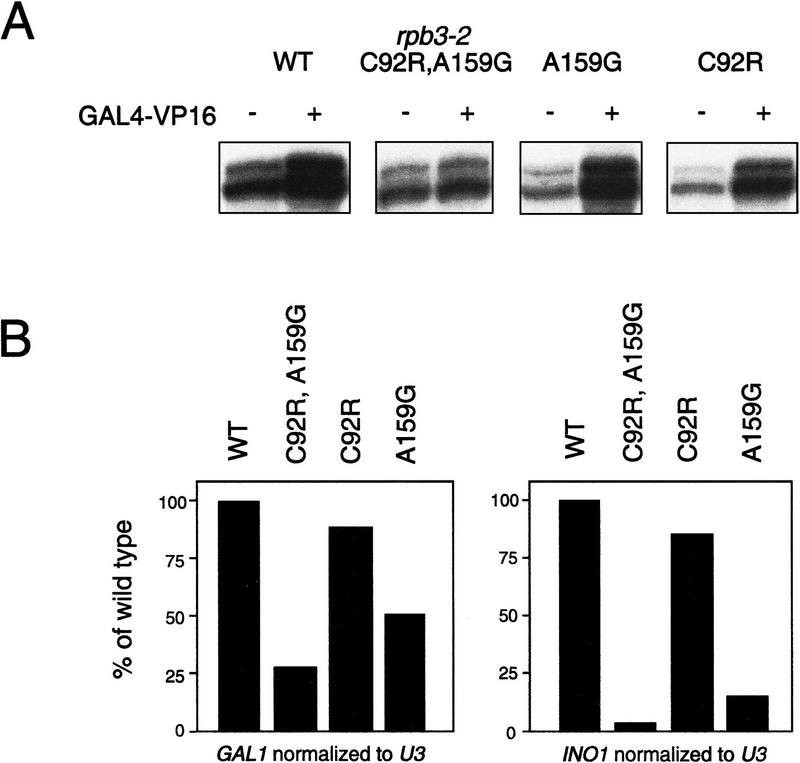

The rpb3-2 allele encodes a subunit with two amino acid substitutions: C92R and A159G. To determine whether C92R, A159G, or both substitutions, contribute to the defect in activator-dependent transcription, we analyzed the effects of the C92R and A159G substitutions separately (Fig. 6). The results indicate that both substitutions are required for the full defect in activator-dependent transcription—both in vitro (Fig. 6A) and in vivo (Fig. 6B). In vitro transcription with extracts from cells containing either wild-type RPB3, the mutant pair, or either single mutation revealed that only the double mutant is unresponsive to activation by GAL4–VP16 (Fig. 6A). Consistent with these findings, activated levels of INO1 and GAL1 transcripts were typically higher in either single mutant compared with the double mutant (Fig. 6B). We conclude that both C92 and A159 are residues critical for activator-dependent transcription.

Figure 6.

Both rpb3-2 mutations contribute to the activation phenotype. (A) Transcription products (with the assay described in Fig. 3) obtained with wild-type (wt) and mutant (specified above each lane) whole-cell extracts with (+) or without (−) added GAL4–VP16. (B) RNA was prepared from the cells (grown under activating conditions at 30°C) containing the mutations indicated. U3 (RNAP II-transcribed snRNA) was included as a loading control, GAL1 and INO1 transcripts were normalized to U3 and graphed relative to the activated wild-type control.

Synthetic enhancement of phenotypes suggest a functional interaction between the 92 and 159 regions

rpb3-2 (C92R;A159G) exhibits a conditional growth phenotype: lethality at 37°C (Figs. 2 and 7A). In contrast, the C92R and the A159G mutants grow normally both at 30°C and 37°C (Fig. 7A). Therefore, the conditional growth phenotype of rpb3-2 (C92R;A159G) results from synthetic enhancement (in this case, synthetic lethality at 37°C) of the C92R and A159G phenotypes. Synthetic enhancement of phenotypes of mutations in a single gene suggests functional relationship between sites of mutations (Guarente 1993).

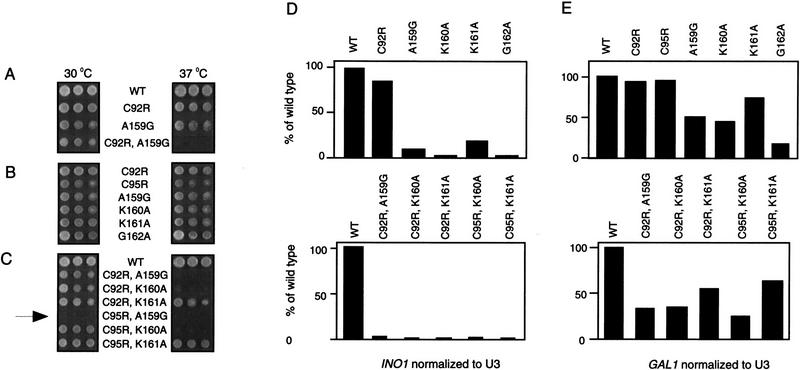

Figure 7.

Synthetic enhancement between residues from the RPB3 92 and 159 regions. (A–C) Equal amounts of yeast cells from strains with the indicated mutant forms of RPB3 were spotted onto YPD plates containing 5-FOA and tested for growth at the temperatures indicated. The arrow highlights the mutant strain that is synthetically lethal at both temperatures. (D,E) RNA was prepared from the wild-type cells or selected double mutants (grown under activating conditions at 30°C) in the 92 and 159 regions as indicated. Histograms represent activated levels of expression of either the INO1 (D) or GAL1 (E) mRNA relative to the activated wild-type control normalized to the U3 (RNAP II-transcribed snRNA) loading control.

We have also constructed and analyzed five additional double mutants altered in the 92 and 159 regions (Fig. 7C). Three of the five double mutants exhibited synthetic lethal phenotypes: Two were lethal at 37°C; one was lethal at 30°C and 37°C (Fig. 7C). In contrast, single mutants in the 92 and 159 regions grew normally, both at 30°C and 37°C (Fig. 7B). These additional examples of synthetic enhancement are consistent with a functional interaction between the 92 and 159 regions.

Finally, we looked for a correlation between growth phenotype and activation phenotype in the single and double mutants. The K160A, K161A, and G162A substitutions resulted in detectable defects in activator-dependent transcription at GAL1 and INO1 in vivo, whereas the C95A mutant (like the C92R mutant shown in Fig. 6B) did not significantly affect activation. However, all double mutants tested displayed more pronounced defects in activator-dependent transcription than the component single mutants (Fig. 7D,E), indicating that growth phenotypes and activation phenotypes are, at least in part, correlated. (Acquisition of temperature sensitivity was associated with impaired activation; however, the ability to grow at 37°C was not tightly correlated with normal activation of GAL1 or INO1.) Overall, we conclude that the residues critical for activator-dependent transcription span (minimally) 92–95 and 159–162 (Fig. 1A, red bars).

The 92 and 159 regions are adjacent to each other

The 92 region is located in a nonconserved region between CR2 and CR3 (Fig. 1A). Residues 92 and 95 are part of the sequence 86C-X-C X3-C-X2-C95, a presumed zinc binding site (Treich et al. 1991). The 159 region is located at the end of CR5 (Fig. 1A). Residues 159–162 map to the end of β-strand 9 in bacterial RNAP αNTD (Fig. 1A).

In the homology-modeled structure of the RPB3/RPB11 heterodimer, the 92 region and the 159 region are adjacent and likely to interact with each other (Fig. 8B)—consistent with the observed synthetic enhancement of phenotypes in the 92 region and 159 region mutants (see preceding section). We infer that the 92 and 159 regions constitute a single determinant specifically required for activator-dependent transcription, that is, a single activation target.

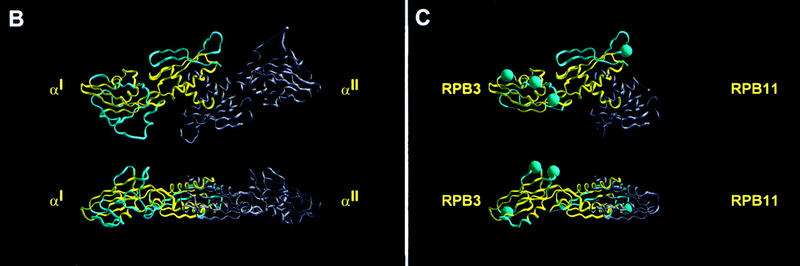

Figure 8.

Location of activation target in αNTDI and RPB3. (A) Crystallographic structure of the E. coli RNAP αNTDI/αNTDII homodimer (two orthogonal views; Zhang and Darst 1998). αNTDI is in light blue; αNTDII is in gray; regions that interact with the second-largest and largest subunits of RNAP II are highlighted in green and blue, respectively (Heyduk et al. 1996). The characterized activation target within αNTDI—required for response to CAP at class II CAP-dependent promoters (Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999)—is represented as an orange sphere. (B) Homology-modeled structure of S. cerevisiae RPB3/RPB11 heterodimer (two orthogonal views; see Fig. 1C). RPB3 is in light blue; RPB11 is in gray. Regions predicted to interact with the second-largest and largest subunits of RNAP II are highlighted in green and blue. The two regions that define the activation target in this work—required for response to GAL4–VP16, GAL4, PHO4, INO2, and ADR1 at tested promoters—are represented as red spheres (with the 92 region slightly above and to the left of the 159 region in each view).

In the homology-modeled structure of the RPB3/RPB11 heterodimer, the 92 and 159 regions are prominently exposed on the surface of RPB3/RPB11 and on the face of RPB3/RPB11 opposite that predicted to interact with the second-largest and largest subunits of RNAP II (Fig. 8B). We infer that the 92 and 159 regions are available, in principle, to participate in macromolecule–macromolecule interactions directly involved in transcription activation.

The 92 and 159 regions are well separated from all determinants of RPB3 known (Kolodziej and Young 1991; Ulmasov et al. 1996; Svetlov et al. 1998; Mitobe et al. 1999) or predicted (Fig. 8B) to be involved in RPB3/RPB11 heterodimerization and RNAP II assembly—consistent with immunoprecipitation results demonstrating assembly of the rpb3-2 (C92R;A159G) subunit with RNAP II and correct stoichiometry of the RNAP II in mutant cells (data not shown). We infer that the defect in activator-dependent transcription of rpb3-2 (C92R;A159G) is not a secondary consequence of defects in RPB3/RPB11 heterodimerization or RNAP II assembly.

The 92 and 159 regions correspond to a characterized activation target in bacterial RNAP αNTDI

In the homology-modeled structure of the RPB3/RPB11 heterodimer, the location of the 92 and 159 regions of RPB3 corresponds to a characterized activation target within bacterial RNAP αNTDI (Fig. 8, cf. A and B; Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999). The 92 and 159 regions are located in the subdomain of RPB3 that corresponds to the subdomain of αNTDI that contains the activation target, and on the face of the subdomain that most nearly corresponds to the face that contains the activation target (Fig. 8). The 159 region of RPB3 is located in CR5, which, in αNTD, immediately precedes the first residue of the loop containing the activation target (Fig. 1a, cf. second red bar with orange bar).

In bacterial RNAP, this activation target mediates response to transcriptional activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP; also known as cyclic AMP receptor protein CRP) at one class of CAP-dependent promoters (Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999). The activation target functions to direct protein–protein interactions with a four amino acid determinant within CAP (activation region 2, AR2; Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999). Experiments with oriented αRNAP derivatives carrying one wild-type and one mutant α subunit indicate that the activation target is functionally presented in only one of the two copies of αNTD in RNAP, that is, αNTDI (Niu 1998; Busby and Ebright 1999).

Implications for activation

Our results indicate that the 92 and 159 regions of RPB3, together, constitute an activation target specifically required for activator-dependent transcription both in vitro and in vivo. We propose that this activation target participates in a direct protein–protein interaction required for transcriptional activation. Possible candidates include an RPB3-activator interaction, an activator-dependent RPB3-coactivator interaction, or an activator-dependent RPB3 general transcription factor interaction. The observation that the activator target in RPB3 is required for response to at least five different activators—GAL4–VP16, GAL4, PHO4, INO2, and ADR1—leads us to disfavor models involving direct RPB3-activator interaction and to favor models involving an activator-dependent RPB3 coactivator or RPB3 general transcription factor interaction. The location of the activation target in the homology-modeled structure of RPB3 corresponds to the location of a characterized activation target within the structure of bacterial RNAP αNTDI (Fig. 8; Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999). The activation target within αNTDI functions through a protein–protein interaction with a factor that binds to a DNA site that overlaps the core promoter and has a precisely defined spatial relationship relative to the core promoter [such that repositioning the DNA site by a single base pair reduces or eliminates function (Gaston et al. 1990; Valentin-Hansen et al. 1991; Busby and Ebright 1999)]. To the extent that the activation target within RPB3 is analogous to the activation target in αNTDI, this would further tend to disfavor models involving direct RPB3 activator interaction (because the activators shown to be affected—GAL4–VP16, GAL4, PHO4, INO2, and ADR1— function from DNA sites at varying distances from the core promoter).

We note that the activation target within αNTDI functions at a step subsequent to recruitment of RNAP to promoter DNA, facilitating isomerization of the RNAP promoter closed complex to the RNAP promoter open complex (Niu et al. 1996; Busby and Ebright 1997,1999; Rhodius et al. 1997). It is attractive to speculate that the activation target within RPB3 likewise functions at a step subsequent to recruitment, and that at this region within RNAP—bacterial or eukaryotic—there is a conserved, specific structural feature (a button or switch) that permits response to postrecruitment activation. This speculation would provide an explanation for the conservation of an activation target in bacteria and eukaryotes.

Materials and methods

Media, yeast strains, and plasmids

Rich medium (YPD), synthetic complete (SC), and minimal medium were prepared from standard recipes (Treco and Lundblad 1993). 5-Fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA) used in plasmid shuffle experiments was added to 1 mg/ml (Boeke et al. 1987). The wild-type and isogenic mutant rpb3-2 strains were named WY-95 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 HIS4-912δ lys2-128δ rpb3D1::LYS2 [pRP37]) and WY-96 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 HIS4-912δ lys2-128δ rpb3D1::LYS2 [pRP38]), respectively. pRP37 is a LEU2 CEN plasmid with a 1.9-kb RPB3-containing SacI–PstI fragment ligated to the corresponding sites of pRP415 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). pRP38 was isolated after PCR mutagenesis (Muhlrad et al. 1992) and is the same as pRP37 but contains two mutations resulting in two amino acid changes, C92R and A159G. WY-95 and WY-96 were created by transformation of Z242 (Kolodziej and Young 1989) with pRP37 and pRP38, respectively, followed by exposure to 5-FOA. All other mutants used in this study were prepared by site-directed PCR mutagenesis (Ho et al. 1989) of pRP37. Once the changes were verified by sequence analysis, the plasmids were transformed into Z242, followed by exposure to 5-FOA.

Sequence alignment

Sequences of bacterial αNTD from Escherichia coli (RPOA_ECOLI), Haemophilus influenzae (RPOA_HAEIN), Bacillus subtilis (RPOA_BACSU), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (RPOA_MYCTU), Borrelia burgdorferi (RPOA_BORBU), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (RPOA_MYCPN), Thermotoga maritima (RPOA_THEMA), Archaeal RpoD from Methanococcus jannaschii (RPOD_METJA), Haloarcula marismortui (RPOD_HALMA), Pyrococcus horikoshii (RPOD_PYRHO), Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (RPOD_SULAC), Sulfolobus solfataricus (RPOD_SULSO), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (RPOD_METTH), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (RPOD_ARCFU), Aeropyrum pernix (BAA80745); RPB3 from S. cerevisiae (RPB3_YEAST), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (RPB3_SCHPO), Mus musculus (RPB3_MOUSE), Homo sapiens (RPB3_HUMAN); RPC5 (AC40,RPA5) from S. cerevisiae (RPC5_YEAST), S. pombe (AF082512), M. musculus (RPA5_MOUSE), H. sapiens (RPA5_HUMAN) were obtained from SWISSPROT or GenBank (accession numbers in parentheses). The sequence of αNTD from Thermus aquaticus was obtained from K. Severinov (Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ). Multiple sequence alignment was performed by use of AlignX (InforMax, Inc.) with ClustalX-based alignment of sequences of bacterial αNTD, followed by successive iterations of profile-based alignments of sequences of RpoD, RPB3, and RPC5 (blosum 62 mt2 score matrix, gap opening penalty = 10, gap extension penalty = 0.05; manual editing after each iteration).

Molecular modeling

Atomic coordinates for E. coli αNTD at 2.5 Å resolution (Zhang and Darst 1998) and T. aquaticus at 3.3 Å (Zhang et al. 1999) were obtained from S. Darst (Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Electron density data for S. cerevisiae RNAP II at 6 Å resolution (Fu et al. 1999) were obtained from Jinhua Fu and Roger Kornberg (Stanford University, CA), converted to INSIGHTII contour file format and rendered as an INSIGHTII contour object. Atomic structures and contour objects were viewed and manipulated in INSIGHTII.

In vitro transcription assays

Whole-cell extracts from wild-type (WY95) and mutant (WY96) strains were prepared as described previously (Wootner et al. 1991). Promoter-specific transcription reactions were based on published procedures (Liao et al. 1991), performed at 23°C for 30 min with 300 μg of extract and 300–500 ng of template plasmid pGAL4CG, in a 25 μl reaction mixture, and initiated by addition of nucleotides. For activated transcription, pGAL4CG− was incubated with GAL4–VP16 for 5 min on ice before starting the transcription reaction. The nonselective, promoter-independent transcription assays were performed as described previously (Liao et al. 1991) except that the same whole-cell extracts used in the promoter-specific transcription assay were used instead of crude cell extracts.

β-Galactosidase assays and Northern analysis

The lacZ reporter plasmids pJH359, pLGSD5, pN703, and pADCY4, containing a CYC1 TATA element and either the INO1, GAL1, PHO5, or ADH2 UAS elements, respectively, or JK103 (lexA(op)–Gal1/10TATA–lacZ)—containing four LexA-binding sites–were separately transformed into WY95 (wild type) and WY96 (rpb3-2). Cells with JK103 also contained plasmids expressing either LexA alone or LexA fused to amino acids 1–220 of Adr1 (trans-activation region I) (Chiang et al. 1996). Cells were harvested after exposure to nonactivating or activating growth conditions (described below). Cell extracts were prepared, enzyme levels assayed, and unit calculations were performed according to standard methods (Kaiser et al. 1994).

For Northern analysis of INO1, cells were grown at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase in minimal medium containing 400 μm inositol. Cells were washed followed by incubation with agitation for 10 hr in the minimal medium containing 10 μm inositol. For analysis of GAL1 expression, cells were grown to mid-logarithmic phase at 30°C in SC medium containing 2% raffinose, collected by centrifugation and washed, then incubated for 3 hr at 30°C in SC containing 5% galactose. For HIS4, cells were grown at 30°C in SD medium supplemented with lysine and adenine to mid-log phase. 3-Aminotriazole was added to a final concentration of 10 mm, followed by incubation with agitation for 3 hr at 30°C. The mutant and isogenic wild-type strain have a mutation (HIS4-912δ) that results in a His- phenotype due the preferential synthesis of an aberrant mRNA (Winston et al. 1984). However, a small percentage of normal mRNA is also synthesized, allowing us to compare induction of HIS4 in the mutant relative with the isogenic wild-type strain. For PHO5, cells were grown at 30°C in either low-phosphate YPD or high-phosphate YPD, cultures were started at OD600 of 0.01, and harvested at an OD600 of ∼0.5. In low- and high-phosphate YPD, potassium phosphate was added to a final concentration of 0.1 and 7.5 mm, respectively. For ADH2, cells were grown at 30°C in medium containing 2% ethanol plus 2% glycerol to an OD600 of 0.6.

Total RNA was prepared by standard methods (Kaiser et al. 1994). Total RNA (15 μg) was loaded into each lane in Northern gels, and 20 μg was loaded to each compartment for dot blots. mRNA levels for dot blots were assessed by hybridization with an excess of (poly)dT oligonucleotide. Both Northern and dot blots were hybridized with radioactively labeled DNA and band intensities quantified with a PhosphorImager. The plasmid names and fragment sizes used as gene-specific probes were as follows: INO1 (pN333) 0.9-kb HindIII–ClaI; GAL1 (pGAL1–GAL10) 2.1-kb EcoRI; TUB2 (pYST138) 0.25-kb HindIII–KpnI; U3 (pJD161) 0.5-kb BamHI–HpaI; PHO5 (pN973) 625-bp BamHI–SalI; HIS4 (pFW45) 1.4-kb EcoRI–SalI.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Darst, J. Fu, and R. Kornberg for structural data and Danny Reinberg and Michael Hampsey for valuable scientific discussions. We also thank the members of the Hampsey laboratory, especially Wei-Hua Wu and Zu-Wen Sun, for providing advice and reagents. Sun Joon Kim kindly provided purified RNAP II for in vitro reconstitution experiments. Finally, we thank Michael Hampsey and Takenori Miyao for critical reading of the manuscript. We obtained generous gifts of purified GAL4–VP16 from the Reinberg laboratory and Sha-Mei Liao. Strains and plasmids were kindly provided by K. Arndt, A. Hammell (J. Dinman laboratory), C. Denis (ADH2 plasmids), Wei-Hua Wu, and the M. Hampsey laboratory. This work was funded by grant no. RPG-97-062-01-NP from the American Cancer Society to N.A.W. and supported by National Institutes of Health grant nos. GM41376 and GM53665 and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigatorship to R.H.E. N.A.W. is a recipient of an American Cancer Society Junior Faculty Award.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL woychina@umdnj.edu; FAX (732) 235-5037.

References

- Boeke JD, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink GR. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby S, Ebright RH. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP) J Mol Biol. 1999;293:199–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YC, Komarnitsky P, Chase D, Denis CL. ADR1 activation domains contact the histone acetyltransferase GCN5 and the core transcriptional factor TFIIB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32359–32365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebright RH, Busby S. The Escherichia coli RNA polymerase α subunit: Structure and function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrem ST, Ross W, Gaal T, Chen ZW, Niu W, Ebright RH, Gourse RL. Bacterial promoter architecture: Subsite structure of UP elements and interactions with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:2134–2147. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanciulli M, Bruno T, Di Padova M, De Angelis R, Lovari S, Floridi A, Passananti C. The interacting RNA polymerase II subunits, hRPB11 and hRPB3, are coordinately expressed in adult human tissues and down-regulated by doxorubicin. FEBS Lett. 1998;427:236–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Gnatt AL, Bushnell DA, Jensen GJ, Thompson NE, Burgess RR, David PR, Kornberg RD. Yeast RNA polymerase II at 5 Å resolution. Cell. 1999;98:799–810. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K, Bell A, Kolb A, Buc H, Busby S. Stringent spacing requirements for transcription activation by CRP. Cell. 1990;62:733–743. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt J. RNA polymerase II holoenzyme and transcriptional regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:310–319. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. Synthetic enhancement in gene interaction: A genetic tool come of age. Trends Genet. 1993;9:362–366. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90042-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyduk T, Heyduk E, Severinov K, Tang H, Ebright RH. Determinants of RNA polymerase α subunit for interaction with β, β′, and ς subunits: Hydroxyl-radical protein footprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:10162–10166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro A, Kimura M, Yasui K, Iwata A, Ueda S, Ishihama A. Two large subunits of the fission yeast RNA polymerase II provide platforms for the assembly of small subunits. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:703–712. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchell A. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Ishihama A. Functional map of the α subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: Amino acid substitution within the amino-terminal assembly domain. J Mol Biol. 1995a;254:342–349. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Functional map of the α subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: Insertion analysis of the amino-terminal assembly domain. J Mol Biol. 1995b;248:756–767. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Ishiguro A, Ishihama A. RNA polymerase II subunits 2, 3, and 11 form a core subassembly with DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25851–25855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej P, Young RA. RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 is an essential component of the mRNA transcription apparatus. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5387–5394. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Mutations in the three largest subunits of yeast RNA polymerase II that affect enzyme assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4669–4678. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.9.4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin RM, Guilfoyle TJ. Reconstitution of yeast and Arabidopsis RNA polymerase α-like subunit heterodimers. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12824–12830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SM, Taylor IC, Kingston RE, Young RA. RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain contributes to the response to multiple acidic activators in vitro. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:2431–2440. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitobe J, Mitsuzawa H, Yasui K, Ishihama A. Isolation and characterization of temperature-sensitive mutations in the gene (rpb3) for subunit 3 of RNA polymerase II in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol & Gen Genet. 1999;262:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s004380051061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad D, Hunter R, Parker R. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast. 1992;8:79–82. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Kimura M, Owens JT, Meares CF, Ishihama A. The two α subunits of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase are asymmetrically arranged and contact different halves of the DNA upstream element. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:1709–1714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer VE, Young RA. RNA polymerase II holoenzymes and subcomplexes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27757–27760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu W. “Identification and characterization of interactions between a transcription activator and the transcription machinery,” Ph.D. thesis. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Niu W, Kim Y, Tau G, Heyduk T, Ebright RH. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters: Two interactions between CAP and RNA polymerase. Cell. 1996;87:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81806-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, West DM, Webster CL, Busby SJW, Savery NJ. Transcription activation at class II CRP-dependent promoters: The role of different activating regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:326–332. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentenac A, Riva M, Thuriaux P, Buhler J-M, Treich I, Carles C, Werner M, Ruet A, Huet J, Mann C, et al. Yeast RNA polymerase subunits and genes. In: McKnight SL, Yamamoto KR, editors. Transcriptional Regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlov V, Nolan K, Burgess RR. Rpb3, stoichiometry and sequence determinants of the assembly into yeast RNA polymerase II in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10827–10830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treco DA, Lundblad V. Preparation of yeast media. In: Janssen K, editor. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, NY: Greene Publishing Associates/John Wiley & Sons; 1993. pp. 13.11.11–13.11.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treich I, Riva M, Sentenac A. Zinc-binding subunits of yeast RNA polymerases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21971–21976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Larkin RM, Guilfoyle TJ. Association between 36- and 13.6-kDa α-like subunits of Arabidopsis thaliana RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5085–5094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin-Hansen P, Holst B, Sogaard-Andersen L, Martinussen J, Nesvera J, Douthwaite SR. Design of cAMP-CRP-activated promoters in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:433–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston F, Chaleff DT, Valent B, Fink GR. Mutations affecting Ty-mediated expression of the HIS4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1984;107:179–197. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootner M, Wade PA, Bonner J, Jaehning JA. Transcriptional activation in an improved whole-cell extract from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4555–4560. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.9.4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RA. RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:689–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.003353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Darst SA. Structure of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase α subunit amino-terminal domain. Science. 1998;281:262–266. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Campbell EA, Minakhin L, Richter C, Severinov K, Darst SA. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 Å resolution. Cell. 1999;98:811–824. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]