Abstract

Rationale

The proper function of cardiac muscle requires the precise assembly and interactions of numerous cytoskeletal and regulatory proteins into specialized structures that orchestrate contraction and force transmission. Evidence suggests that post-transcriptional regulation is critical for muscle function, but the mechanisms involved remain understudied.

Objective

To investigate the molecular mechanisms and targets of the muscle-specific Fragile X mental retardation, autosomal homolog 1 (FXR1), an RNA binding protein whose loss leads to perinatal lethality in mice and cardiomyopathy in zebrafish.

Methods and Results

Using RNA immunoprecipitation approaches we found that desmoplakin and talin2 mRNAs associate with FXR1 in a complex. In vitro assays indicate that FXR1 binds these mRNA targets directly and represses their translation. Fxr1 KO hearts exhibit an upregulation of desmoplakin and talin2 proteins, which is accompanied by severe disruption of desmosome as well as costamere architecture and composition in the heart, as determined by electron microscopy and deconvolution immunofluorescence analysis.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal the first direct mRNA targets of FXR1 in striated muscle and support translational repression as a novel mechanism for regulating heart muscle development and function, in particular the assembly of specialized cytoskeletal structures.

Keywords: Cytoskeletal dynamics, mRNA binding proteins, Desmosome, Heart development

Proper contraction of striated muscle requires strict assembly and coordination of its unique cytoskeletal components including sarcomeres,1 costameres2,3 and specialized membrane junctional complexes.4 The mechanisms by which muscle cells precisely orchestrate the formation of these inherently dynamic and specialized cytoskeletal structures remain uncertain. In this study, we used a combined molecular and genetic approach centered on the RNA binding protein Fragile X mental retardation, autosomal homolog 1 (FXR1) to investigate the role(s) of RNA regulation in cardiac muscle assembly. FXR1 is a member of the Fragile X (FraX) family of RNA-binding proteins, which has been implicated in several aspects of RNA regulation including mRNA transport, stability and translation.5–7 The majority of studies to date have focused on the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP) due to its linkage to Fragile X Syndrome, the most common form of inherited mental retardation and autism.8

Biochemical experiments indicate that all FraX protein family members associate with RiboNuclear Protein particles (RNPs) and actively translating polyribosomes,9–12 which is consistent with the ability of these RNA-binding proteins to regulate translation of their mRNA targets. In vitro studies show that the FraX proteins possess both common and unique RNA binding properties,13, 14 suggesting that the FraX family members have distinct RNA targets and thus, exert different functional roles. This prediction is further substantiated by the observation that while the FraX proteins exhibit overlapping expression patterns in the nervous system,15, 16 they have unique tissue distributions outside the brain. FXR1 is the only FraX protein with robust expression in cardiac and skeletal muscle;17 to date, its mRNA targets and molecular mechanisms have not been reported in these tissues.

Elimination of Fxr1 leads to perinatal lethality in mice, and reduction of FXR1 protein levels by morpholino treatment causes muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy in zebrafish.18, 19 In addition, FXR1 expression is altered in myoblasts from patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, suggesting that FXR1 may also play a role in human muscle disease.20 Despite the obvious importance of FXR1 in striated muscle development and disease, the functional role of the protein and the identity of mRNA targets in muscle remain unknown.

To elucidate the function of FXR1 and to identify its mRNA targets in the heart, we examined the ultrastructure of cardiac muscle at embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5) in Fxr1 knockout (KO) mice. We found that the ultrastructure and protein composition of the desmosomes and costameres, as well as sarcomere architecture are markedly altered in Fxr1 KO mice. Using antibodies to FXR1-containing complexes we performed RNA-immunoprecipitations (RNA-IPs) and identified candidate targets, desmoplakin (dsp) and talin2 (tln2) mRNAs, whose cognate proteins localize to the desmosomes and costameres, respectively. We determined that FXR1 binds dsp and tln2 mRNAs directly and negatively regulates their translation. These results constitute the first report of mRNA targets for FXR1 in striated muscle and indicate that FXR1 functions as an essential regulator for correct levels of protein expression at desmosomes and costameres in the developing heart.

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the Online Data Supplement and provides details for many of the methods described here plus materials, animals, microscopy, Western blots and antibodies used in this study.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

Talin2 (tln2) mRNA was localized in situ on frozen sections of E18.5 hearts using a protocol adapted from Mankodi et al.21 Frozen sections were fixed and stained with anti-α-actinin antibodies (1:10,000, Sigma) followed by goat anti-mouse Texas Red antibodies (1:600) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). RNA hybridization was performed with the tln2 anti-sense probe for 3h at 37°C in hybridization buffer (30% formamide, 2× SSC, 0.02% BSA, 66 μg/mL yeast tRNA, 2 mM vanadyl complex). The DIG-labeled probe was detected using FITC-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies (1:400) (Roche), followed by Alexafluor-488 conjugated anti-FITC antibodies (1:800) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Samples were imaged on a DeltaVision Deconvolution microscope. Details of the tln2 probe are provided in the Supplemental Data.

RNA-Immunoprecipitations (RNA-IP)

FXR1 RNA-IPs were performed according to the protocol described in Brown et al.22 with slight modifications. Tissue was ground over liquid N2 then suspended in 2mL IP buffer/heart. Lysates were added to protein A beads with either 10μg of affinity-purified rabbit anti-FXR1 antibodies, or the antibodies pre-competed with 10 molar excess of antigenic peptide and immunoprecipitated at 4°C for 3h. Complexes on beads were washed 3X with IP buffer and then 3X with IP buffer plus 1M urea to decrease secondary protein interactions.23 The samples were resuspended in 100μl nuclease-free water: 20% for protein analysis and 80% for RNA extraction. RNA was quantified and normalized from all samples, which was then used in candidate real-time PCR to identify enrichment of target mRNAs.

Real-time PCR

cDNA was generated from RNA isolated from whole hearts for assessment of total transcript levels, or from RNA-IP experiments and used as template in real-time PCR using SYBR green chemistry (Fermentas). Primers to candidate genes are listed in Online Table I. A housekeeping gene (Odc1) was used to normalize loading for total transcript studies. Primer efficiencies were validated to be within 5% of the housekeeping gene primers so that alterations in total mRNA levels could be assessed by using the 2−ΔΔCT method.24

Cell Culture and Luciferase Assays

COS-7 cells were maintained according to ATCC guidelines and co-transfected with FLAG-Fxr1 (the longest muscle isoform e) and pmirGLO dual luciferase vector containing a multi-cloning site in the 3′UTR of firefly luciferase (Promega). The multi-cloning site downstream of luciferase was cloned to contain β-2-microglobulin (negative control), the open reading frame of FXR1, or the 3′UTRs of dsp and tln2 (see Online Figure I for schematic of cloning strategies). Transfected cells were allowed 48h to express exogenous proteins before luciferase assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Six independent luciferase assays were performed in technical triplicate.

Direct RNA-Protein Binding Assays

The 3′UTR of dsp and tln2 mRNAs and full length β2-microglobulin (negative control) were in vitro transcribed and labeled with biotin (Epicentre Biotechnologies). Recombinant FXR1 was expressed and purified from bacteria following published protocols.25 Approximately 40 pmol biotin-RNA was immobilized on streptavadin beads (Invitrogen), incubated with recombinant FXR1 (~40ng) and washed under published buffer conditions.26 A positive interaction was detected by probing a Western blot for the presence of recombinant FXR1 after the RNA-protein mixture was run on 7.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose.

Statistics

A paired Student’s t-Test was used to determine significance for quantitative Western and luciferase assays. An a priori power analysis was conducted using preliminary data collected for luciferase assays to determine the sample size required. A threshold for noteworthy changes in total mRNA levels assessed by real-time PCR was set at a 2-fold change using the 2^(−ΔΔCT) method.24

Results

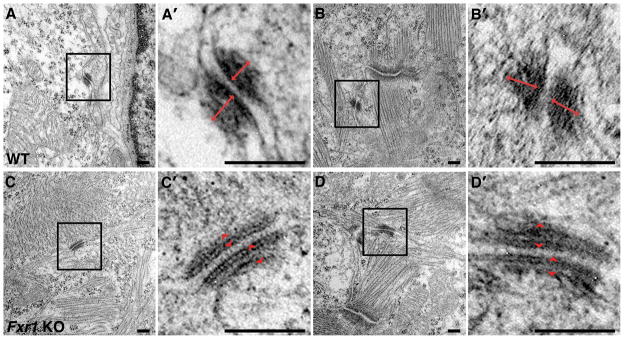

Desmosome architecture is disrupted in hearts lacking FXR1

To better understand the basis of the perinatal lethality of Fxr1 KO mice, we isolated hearts at E18.5 and evaluated them by electron microscopy. Wild type hearts exhibit desmosomes containing characteristic dense inner plaques, consisting of intermediate filaments, which are tethered to the membrane via desmoplakin. In contrast, desmosomes in Fxr1 KO hearts have inner dense plaques that are less defined, extend less into the cell, with intermediate filaments appearing incompletely attached to the desmosomal membranes (Figure 1). Furthermore, the long face of the desmosomal junctions is on average ~27% longer in the Fxr1 KO hearts compared to wild type (210.96±68.64 nm (N=41) vs. 165.95±45.89 nm (N=33), respectively (p < 0.05)). The lengthening of the desmosome junction in Fxr1 KOs is consistent with a decrease in intermediate filaments (Figure 1C′ and D′). These data indicate that desmosome architecture is altered in mice deficient for FXR1.

Figure 1.

Loss of FXR1 causes disruption of the inner dense plaque of desmosomes.

In WT hearts (A & B), inner dense plaques are prominent, where intermediate filaments anchor to the membrane of the desmosome (double-headed red arrows). Loss of FXR1 in the KO hearts (C & D) results in reduced inner dense plaques at desmosomes (red arrowheads). Panels labeled A′–D′ are higher magnification views of the boxed areas in A–D. N=2 per genotype. Bars = 250 nm.

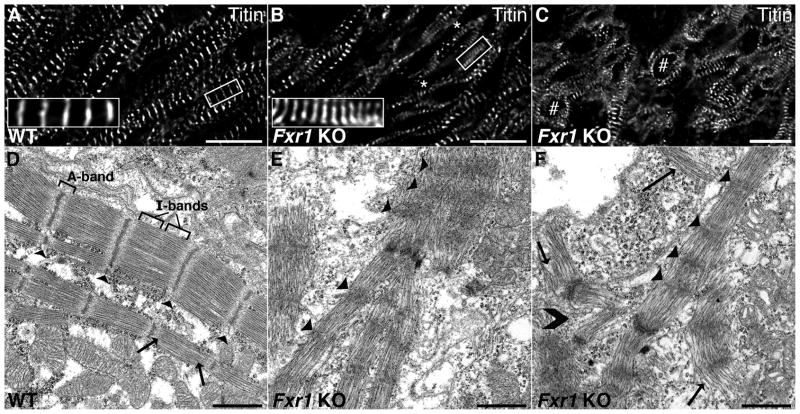

Loss of FXR1 leads to defects in sarcomere structure and lateral adherence of myofibrils

Further analyses of the Fxr1 KO heart showed striking alterations in myofibril architecture by electron and immunofluorescence deconvolution microscopy. Wild type hearts exhibit mature, narrow, evenly spaced Z-discs, as well as myofibrils that are laterally aligned and tightly bundled (Figure 2A and D). In contrast, the Fxr1 KO hearts display areas containing sarcomeres of shortened length (averaging 1.31 ± 0.40μm (N=240), compared to 1.68± 0.18μm (N=150) in wild type (Figure 2)). While the measured sarcomere lengths appear shorter than the reported working range of sarcomere lengths (~1.7–2.2μm as described by Page, S.27 and reviewed by Allen et al.28), it is important to note that the animal hearts were not prepared under relaxing conditions. Furthermore, in the areas of altered sarcomeric spacing, the myofibrils appear to “splay out” and lose their lateral connections (Figure 2C). These phenomenon were also observed at the ultrastructural level, where the Fxr1 KO mice show widened Z-discs, inconsistent sarcomere lengths (Figure 2E) and “curving” of myofibrils as they lose lateral contact with their neighbors (Figure 2F). Wild type hearts, conversely, exhibit well-ordered and spaced sarcomeres with narrow Z-discs, well-aligned filaments and highly distinguishable I- and A-bands (Figure 2D). When sections of the entire Fxr1 KO heart were visualized by light microscopy, large regions of disrupted tissue were interspersed amongst areas where the architecture looked comparable to wild type creating a mosaic-like appearance (Figure 2B). Together, the morphological analyses of Fxr1 KO hearts are consistent with defects in development of the costamere, a specialized cytoskeletal assembly known to function in lateral alignment of myofibrils and sarcomeric spacing during early myofibrillogenesis.2, 29

Figure 2.

Loss of FXR1 leads to defects in sarcomere spacing and structure, and lateral adherence of myofibrils. Immunofluorescent localization of Z-disc titin shows even spacing and alignment of sarcomeres in WT hearts (A). Sarcomere spacing is erratic and shortened in Fxr1 KO hearts (1.31±0.40μm (N=240), compared to 1.68±0.18μm (N=150) in WT hearts (p < 0.05) (B, asterisks). Myofibrils also lose lateral bundling and “splay” out in the KO hearts (C, noted by #). Electron micrographs of WT hearts reveal evenly spaced Z-discs (arrowheads), organized thick filaments (arrows) within sarcomeres and clearly aligned myofibrils (D). In contrast, Z-discs (arrowheads in E & F) are variably broad, disorganized and unevenly spaced in KO hearts (E); disorganized thick filaments are apparent (F, arrows). Additionally, the lack of lateral bundling of myofibrils is observed in the KO hearts (F, noted by >). Bars in A–C = 15μm, D–F = 1μm.

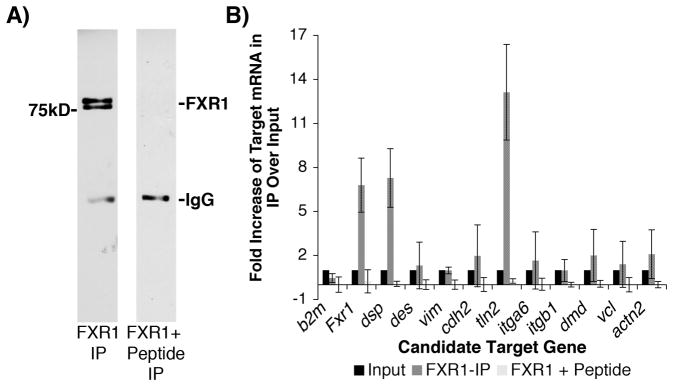

Desmoplakin and talin2 mRNAs are enriched in the FXR1 protein complex

Based on the prominent structural alterations observed in the Fxr1 KO hearts, we sought to determine whether mRNAs encoding any major cell junction or costamere proteins might be targets of FXR1 regulation. As a first step we used an antibody against FXR1 to isolate FXR1 protein-RNA complexes (RNA-IPs) from wild type mouse hearts (Figure 3A). To determine specificity, the FXR1 antibody was pre-competed with antigenic peptide before addition of the heart extract. To identify mRNAs associated with FXR1, we took a candidate qPCR approach using primers designed to detect transcripts whose cognate proteins are known to localize at costameres and desmosomes. Transcripts were considered to be associated with the FXR1 protein and pursued for further study if they were reproducibly enriched in the FXR1 RNA-IP by >2-fold over input RNA and the negative control IP.

Figure 3.

Dsp and tln2 mRNAs are enriched in the FXR1 protein complex. (A) FXR1 was immunoprecipitated from adult mouse heart lysate (left lane) or the anti-FXR1 antibodies were competed with their antigenic peptide to establish specificity (right lane) (N=3). RNA isolated from immunoprecipitations was quantified and matched to amounts of total input RNA prior to qPCR analysis. Real-time PCR was used to assess the enrichment of candidate mRNA targets in the FXR1-IP compared to input RNA and control IP RNA (B). Beta-2-microglubulin (b2m) RNA is a negative control not associated with the FXR1 complex. Data shown as fold change (2^-(IPCt-InputCt)) ± SD. * = reproducible >2-fold change. Fxr1, dsp and tln2 are enriched in the FXR1 complex 6.8-, 7.3-, and 13.1-fold, respectively.

Of the candidate mRNA targets tested, only dsp and tln2 transcripts are reproducibly enriched in the FXR1 RNA-IPs (7.3-fold and 13.1-fold, respectively) (Figure 3B). Additional candidates tested included dystrophin (dmd) and vinculin (vcl) whose cognate proteins were shown to be mislocalized in the heart muscle of Fxr1 KO animals,18, 19 as well as other cell junction mRNAs such as desmin (des), vimentin (vim), integrin-α6 (itga6), integrin-β1 (itgb1) and N-cadherin (cdh2) (Figure 3B). In addition, Fxr1 mRNA itself is enriched in the RNA-IP relative to controls (6.8-fold), suggesting that FXR1 may regulate its own expression (Figure 3B). The identification of dsp and tln2 mRNA transcripts associated with FXR1 protein in striated muscle is remarkably consistent with the disrupted desmosomes and costameres observed in Fxr1 KO hearts (Figures 1 and 2).

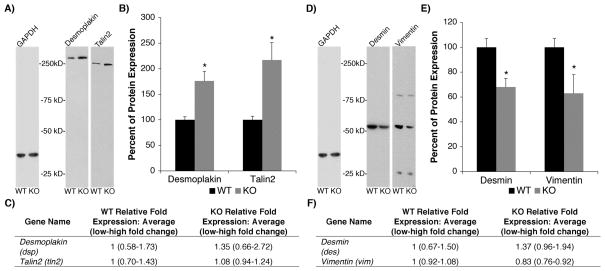

Loss of FXR1 in the heart leads to changes in desmoplakin, talin2 and intermediate filament protein levels

To determine the molecular mechanisms by which FXR1 may control the expression of dsp and tln2 mRNAs, we carried out Western blots and examined the levels of desmoplakin and talin2 proteins in E18.5 Fxr1 KO hearts. Densitometric analysis revealed a reproducible, significant increase in protein levels of desmoplakin (76.3%, p < 0.05) and talin2 (117.3%, p < 0.05) in Fxr1 KO compared to wildtype hearts (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Desmoplakin and talin2 protein levels are upregulated in Fxr1 KO mouse hearts. (A) Representative Western blots performed on WT and KO heart lysates for candidate targets enriched in the FXR1 protein complex: desmoplakin and talin2. (B) Quantification shows the percent increases in protein expression in the KO compared to the WT mouse hearts after normalization to GAPDH. Desmoplakin and talin2 protein levels are up in KO hearts 76±19% and 117±34%, respectively. (C) Total mRNA of target molecules dsp and tln2 are unchanged in KO compared to wild type hearts. (D) Representative Western blots of non-target molecules desmin and vimentin. (E) Non-target proteins desmin and vimentin are down regulated in KO hearts by 32±4% and 37±15%, respectively after normalization to GAPDH. Total mRNA of non-targets des and vim (F) are unchanged in KO compared to wild type hearts. Samples were normalized to Odc housekeeping gene and analyzed using the ΔΔCT method24 (2^-(ΔCTtarget-ΔCTodc)). No notable alterations in total transcript levels of any candidate genes were detected, as defined by a reproducible >2-fold change. N=4 per genotype for both protein expression and total mRNA studies. Protein expression levels provided as mean ± SD. * = p < 0.05.

Due to the clear reduction in observable inner dense plaques at desmosomes in the Fxr1 KO hearts, we also analyzed the levels of the two most abundant intermediate filament proteins in striated muscle, desmin and vimentin. Even though their mRNAs were not enriched in the FXR1 complex (Figure 3B), desmin and vimentin protein levels were significantly decreased in Fxr1 KO hearts to ~67% and ~63% of wild type levels, respectively (p < 0.05) (Figure 4D and E). These results are consistent with the scarcity of intermediate filaments at the desmosome (Figure 1).

Next, we asked whether alterations in the protein levels of the FXR1 targets desmoplakin and talin2 were due to effects on the steady-state transcript levels in the Fxr1 KO mouse hearts. Additionally, we investigated steady-state levels of non-target molecules, desmin and vimentin. Quantitative real-time PCR showed no changes in total transcript levels of dsp, tln2, des or vim mRNAs (Figure 4C and F). Thus, our findings indicate that the substantial alterations in protein composition of the desmosome and costamere in Fxr1 KO hearts is likely due to a posttranscriptional mechanism. Given our RNA-IP results (Figure 3), our data suggest that FXR1 directly regulates the expression of desmoplakin and talin2, while the downregulation of desmin and vimentin proteins is likely an indirect consequence of FXR1 loss in the heart. These results underscore the importance of our combined molecular and genetic approach that can distinguish between FXR1 direct targets and indirect phenotypic effects that are likely due to alterations in the stoichiometry of junctional protein complexes.

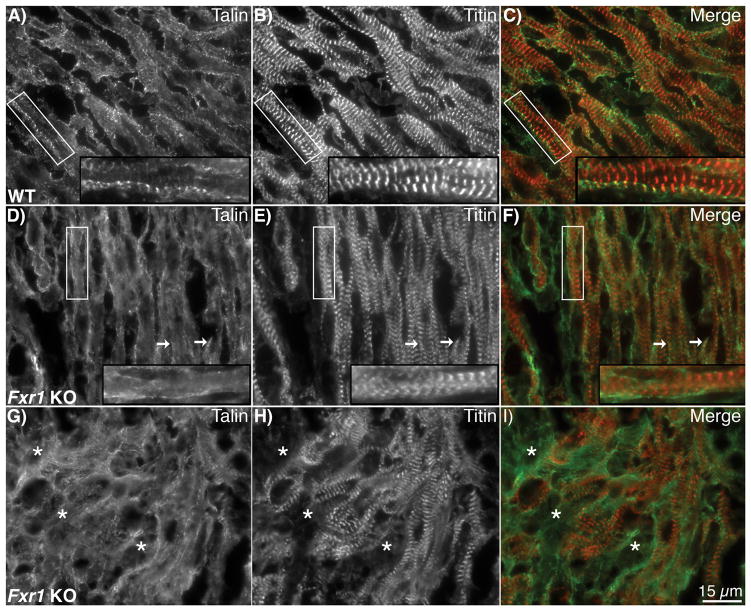

Talin2 localization expands beyond the typical region of the costamere in Fxr1 KO hearts

Identification of dsp and tln2 mRNA as candidate targets of FXR1, coupled with their increased protein levels in the Fxr1 KO hearts prompted us to investigate the localization of these proteins in Fxr1 KO hearts. The analysis was carried out using immunofluorescence deconvolution microscopy since it is difficult (if not impossible) to analyze costameres by thin section transmission electron microscopy. Talin associates with the integrin receptor complex at the costamere and links the myofibrils to the surrounding extracellular matrix. In wild type hearts talin2 protein is localized in a characteristic striated pattern with obvious punctate accumulation at the lateral edges of the myofibrils (localizing over the Z-disc), which is representative of costameric localization (Figure 5A and C). Due to the mosaic-like appearance of the myofibril phenotypes recognized by light microscopy in the Fxr1 KO hearts (Figure 2), talin2 localization was assessed both in areas more similar to wild type (Figure 5D) and in areas that demonstrate disruption (Figure 5G). Interestingly, talin2 protein was rarely confined to the punctate costameric localization in the Fxr1 KO hearts, such that the overall staining was dispersed along the membrane. These data are consistent with the increased talin2 protein levels found in the Fxr1 KO hearts (Figure 4). Unregulated protein expression and mislocalization of talin2 in the Fxr1 KO hearts is consistent with the hypothesis that FXR1 is required for development and/or maintenance of the costamere and is supported by previous reports of the mislocalization of the costameric proteins dystrophin and vinculin in the KO mice.18 Notably, at this developmental time point (E18.5) desmoplakin protein does not exhibit a clear localization pattern in wild type hearts; therefore comparison to Fxr1 KOs was not informative (Online Figure II).

Figure 5.

Talin2 protein localization expands beyond the typical costameric localization in Fxr1 KO mice. Sections of E18.5 hearts were stained for talin (green) and I-band titin (N2A, red). In WT hearts (A–C) talin is found in distinct puncta at costameres near the cell membrane (A, insert). Staining for talin in KO hearts in regions where the sarcomeric architecture looks similar to that of the WT (D–F) displays continuous staining along the length of the membrane in addition to occasional puncta in register with titin (white arrows). Talin localization in disrupted areas (G–I) exhibits staining in gaps lacking titin staining (asterisks). Bar = 15μm.

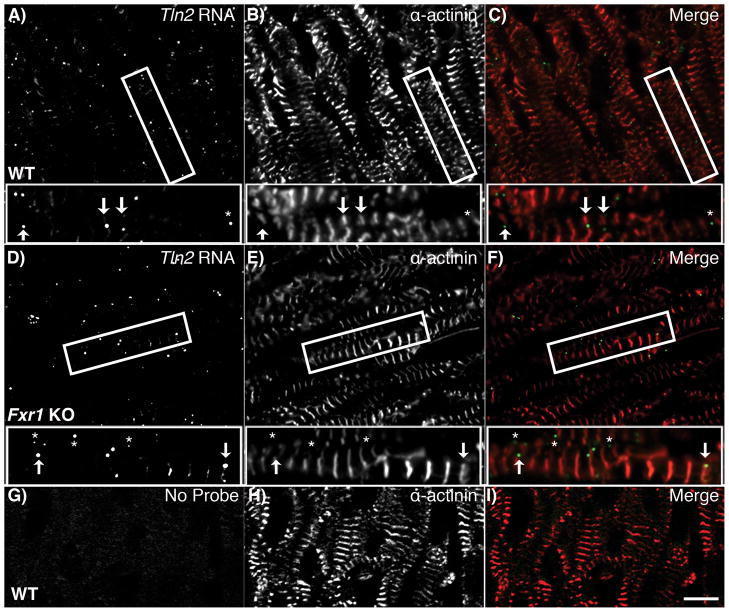

Loss of FXR1 does not perturb tln2 mRNA localization

The altered localization of talin2 protein led us to investigate the possibility that this phenotype is caused by defects in the localization of its mRNA (tln2). One possibility is that in the absence of FXR1, tln2 mRNA may be mislocalized and undergo unrestricted protein synthesis (as suggested by the increased total talin2 protein levels, Figure 4). To test this possibility, we performed Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) to compare the localization of tln2 mRNA on frozen tissue sections of wild type and Fxr1 KO hearts. In wild type hearts, tln2 mRNA localizes to puncta among the myofibrils (see inset Figure 6A and C). There were no notable differences in localization of tln2 mRNA in the Fxr1 KO hearts (Figure 6D and F). The positive tln2 mRNA signal was lost when using no probe controls (Figure 6G & I) and by pre-treating samples with RNase (data not shown). These data indicate that the expanded protein localization of talin2 observed in the Fxr1 KO hearts (Figure 5) is not due to altered tln2 mRNA localization and suggest a model where FXR1 regulates tln2 mRNA expression in the heart by controlling its translation, as has been described in non-muscle systems.30

Figure 6.

Localization of tln2 mRNA is not affected by the loss of FXR1. Sections of E18.5 hearts from WT and KO mice were probed for tln2 mRNA by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) (green). Hearts were co-stained for α-actinin (red). In WT (A–C), and KO (D–F) hearts tln2 mRNA localizes in discreet puncta amongst the myofibrils, relating closely with (arrows) and between (asterisks) Z-discs. Bar = 10μm.

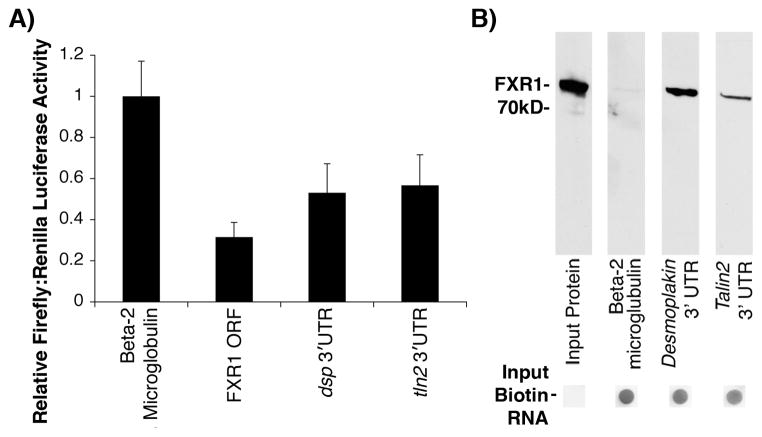

FXR1 binds dsp and tln2 mRNAs and represses their translation in vitro

The observation that protein levels of desmoplakin and talin2 are upregulated with no corresponding changes in total mRNA transcript levels (Figure 4) or localization in the Fxr1 KO hearts (Figure 6) led us to hypothesize that FXR1 acts as a negative regulator of translation for dsp and tln2 mRNAs. To test this, we used dual luciferase assays where the 3′ UTRs of dsp or tln2 were inserted downstream of a Firefly luciferase reporter (pmirGLO) and co-transfected into COS-7 cells with FLAG-FXR1. Transfection efficiency and cell viability were monitored using Renilla luciferase and data are reported as Firefly:Renilla ratios for each experimental sample. Figure 7A shows FXR1 represses the translation of luciferase constructs containing dsp and tln2 3′UTRs, compared to the negative control, β2-microglobulin (whose RNA is not enriched in the FXR1 protein complex (Figure 3B). Luciferase activity was dramatically reduced by ~47% and ~43% from control levels by the 3′ UTRs of dsp or tln2, respectively (p<0.01). Since Fxr1 mRNA was identified in the FXR1 protein complex (Figure 3B) we also tested the ability of FXR1 to regulate the translation of its own mRNA. Based on previously published work, which showed that FMRP binds to its own mRNA within the open reading frame (ORF),26 we inserted the ORF of FXR1 into our luciferase reporter to determine whether FXR1 is also capable of auto-regulation. Indeed, we found that FXR1 protein is capable of repressing the translation of its own mRNA by ~68% from control levels (Figure 7A), suggesting that this function is conserved among the FraX protein family.

Figure 7.

FXR1 directly binds and represses the translation of dsp and tln2 mRNAs in vitro. (A) Data from dual reporter luciferase assays in COS-7 cells (N=6). Firefly luciferase containing Beta-2 microglobulin in the 3′UTR serves as control RNA that is not translationally repressed by FXR1. When the luciferase reporter contains the Fxr1 open reading frame (ORF), the dsp 3′UTR or the tln2 3′UTR, average luciferase activity is repressed to 31.6%, 53.1% and 56.7%, respectively (* = p < 0.01, mean ± SD). (B) Direct protein-RNA binding experiments show recombinant FXR1 binds biotin-dsp 3′UTR, and biotin-tln2 3′UTR RNA, but not biotin-Beta-2 microglubulin 3′UTR (as detected by probing Western Blots for FXR1, after incubation with immobilized biotin-RNA).

Next we tested the ability of FXR1 to bind the 3′UTR of dsp and tln2 mRNAs directly, as suggested by the dual-luciferase assays. To this end the 3′UTRs of dsp and tln2 were in vitro transcribed, labeled with biotin and incubated with purified recombinant FXR1. Figure 7B illustrates that FXR1 protein binds directly to the 3′UTR of dsp and tln2 but not to the β2-microglobulin negative control RNA. Since the steady state levels of dsp and tln2 mRNA were not significantly different in Fxr1 KO versus wild type hearts (Figure 4C and F), our results suggest that FXR1 negatively regulates translation through direct binding to the 3′UTRs of target mRNAs, dsp and tln2 (Figure 7A).

Discussion

Striated muscle has several well-documented requirements for post-transcriptional gene regulation from de novo assembly to protein turnover, contractile regulation and signaling events required for heart development, maintenance and disease (for review see: Clark et al.1). Although many architectural players and accessory molecules in striated muscle have been identified the mechanisms and requirements of post-transcriptional gene regulation involving RNA-binding proteins remain understudied. In this investigation we sought to identify specific mRNA targets and the molecular mechanisms of FXR1, the sole member of the FraX family proteins expressed in striated muscle.

We report the identification of dsp and tln2 as mRNA targets of FXR1 in the heart. We show that FXR1 can directly bind the 3′UTR of dsp and tln2 mRNAs and repress their translation. Consequently, desmoplakin and talin2 proteins are significantly upregulated in the developing Fxr1 KO heart. In addition, select components of the desmosome complexes are altered in Fxr1 KO hearts, likely due to effects on the stoichiometry of these macromolecular complexes. Thus, we report direct FXR1-dependent mechanisms by which cytoskeletal assemblies are controlled specifically, via translational regulation of desmoplakin and talin2 mRNAs in cardiac muscle.

Examination of the KO mouse hearts by electron microscopy revealed altered desmosome architecture with an obvious reduction of the inner dense plaque where the intermediate filaments join the desmosome (via desmoplakin). Mechanistically, the perinatal lethality described in the Fxr1 null mice could be attributed to sudden cardiac arrest due to the dysregulation of desmoplakin, a molecule that has been implicated in proper cardiac function as well as subsequent junctional protein composition and structural alterations.31 Mutations or truncations in desmoplakin have been linked to several human diseases including ventricular arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy (e.g., Carvajal syndrome, Naxos disease and Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy).32–34

Previous studies showed that over-expression of N-terminal desmoplakin, which lacks the intermediate filament binding sites, results in displacement of intermediate filaments from the desmosome,35 which is remarkably similar to our observations in Fxr1 KO hearts. Although loss of FXR1 leads to the upregulation of full-length desmoplakin protein, we speculate that this increase in levels may disrupt the stoichiometry of junctional complexes leading to the observed reduction of inner dense plaques at the desmosome. Quantification of the abundant striated muscle intermediate filament proteins, desmin and vimentin, by Western blot analyses indicated a ~32% and ~ 37% reduction in their levels, respectively. Since des and vim mRNAs do not appear to associate with the FXR1 complex, it is likely that the reduction in the intermediate filament protein levels is a secondary outcome due to increased desmoplakin translation in the absence of FXR1. It is possible that the increased translation of desmoplakin may act in a dominant negative manner to displace intermediate filaments from the desmosome (as in Bornslaeger et al.,35) and/or upset the delicate stoichiometry of desmosomal components, resulting in desmosome remodeling

The initial characterization of the Fxr1 KO mice revealed severe disarray of the musculature.18 Specific proteins of the costamere such as dystrophin, α-actinin and vinculin were reported to have altered localization in the Fxr1 KO mice yet the molecular mechanism underlying these alterations remained unknown. In this study, both light and electron microscopy revealed defects in costamere structure and we identified tln2 as an mRNA target of FXR1 but not dystrophin (dmd), α-actinin (actn2) or vinculin (vcl). Talin is a large (~250 kDa) protein located at cell-matrix contacts that functions to link integrin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton via interactions with vinculin and α-actinin. There are two talin genes (tln1 and tln2) with tln2 being highly expressed in cardiac muscle.36 The absence of dmd, actn2 and vcl in the FXR1 complex, strongly suggests that, mechanistically, upregulation of talin2 protein in the KO heart is the primary cause of the costamere defects and that mislocalization of other costameric proteins is a secondary effect.18

Functionally, the role of talin2 in cardiac muscle is not clearly understood since only the skeletal muscle was characterized in the tln2 KO.37 Ablation of talin2 results in defective myoblast fusion and sarcomere formation of skeletal muscle.37 Since the normal functions of talin2 are to modulate the ligand-binding activity of integrins and integrate signaling pathways,38 alterations in talin2 localization or levels in the Fxr1 KO may disrupt integrin signaling and subsequent interactions with either the extracellular matrix or the cortical actin cytoskeleton. Evidence for a phenotypic consequence of talin upregulation has been demonstrated by overexpression of the N-terminus of talin, which acts as a dominant negative by stimulating integrin receptors via inside-out signaling.39

FXR1 was previously proposed to play a role in costamere development based on its localization adjacent to vinculin and dystrophin at the myoseptum of zebrafish40 and on phenotypic findings in Xenopus, zebrafish and mouse.18, 41, 42 While these studies clearly demonstrated the importance of FXR1 in striated muscle,18, 19, 41 the localization of talin, protein levels of other costameric components (beyond dystrophin, α-actinin and vinculin) and the ability of FXR1 to directly control their expression were not assessed. Our combined molecular and genetic approach distinguishes between direct and indirect mRNA targets and significantly extends previous studies.

It is possible that FXR1 may control dsp, tln2 and other mRNA targets at different times throughout development. Our results show that at E18.5, before lethality occurs in the KO, FXR1 acts as a negative regulator of translation for desmoplakin and talin2. In addition, our results are the first to demonstrate specific interactions between FXR1 and its own transcript and to demonstrate that inhibition of Fxr1 translation is mediated at least in part, through sequences located in the coding region. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that other structural components may be directly regulated by FXR1 earlier in development, the upregulation of desmoplakin and talin2 proteins at E18.5 provide an explanation for alterations (desmosome and costameric assemblies) detected in the mutant heart.

In summary, our findings on FXR1, its novel target mRNAs and the mechanism by which FXR1 regulates their expression and localization provide a foundation for the study of RNA-based mechanisms of muscle biology and disease. Taking into account descriptions of FXR1’s documented association with RiboNuclear Protein particles (RNPs) and actively translating polyribosomes12, 43 and the family member FMRP associating with ~4% of all brain mRNAs,44 it is likely that FXR1 interacts with several transcripts in striated muscle in addition to dsp and tln2 mRNAs. There have been no reports yet of FXR1 mutations or truncations associated with human disease. There is, however, precedent for RNA-binding proteins being linked to dilated cardiomyopathy as mutations in Rbm20, a protein involved in RNA-splicing, have recently been reported.45, 46 Given the importance of FXR1 in cardiac development, it will be important in the future to determine whether FXR1 may play a role in the etiology of human heart disease. To our knowledge, the results presented in this study are the first to directly relate an RNA-binding protein to translational repression of specific targets in cardiac muscle. Our work, combined with other descriptions of RNA-binding proteins in striated muscle,47–49 provide a scenario whereby muscle function and development are governed by the interplay of post-transcriptional RNA regulation including transcript localization, splicing, transcript stability and translational control.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is known?

The Fragile X mental retardation protein family is comprised of structurally similar RNA binding proteins.

Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) in the brain results in cognitive deficits and autistic behaviors due to defects in localized translation of specific target mRNAs.

Fragile X mental retardation, autosomal homolog 1 (FXR1) is the most abundant family member expressed in striated muscle; its loss causes neonatal lethality in mice and cardiomyopathy in zebrafish by unknown mechanisms.

What new information does this article contribute?

We provide the first identification of in vivo mRNA targets of FXR1 in the heart. These encode essential cytoskeletal proteins required for heart development and function.

We demonstrate that FXR1 repress the translation of its target mRNAs, a process that is required for proper cardiac development and function.

Although the importance of RNA-binding proteins is well established in developing embryos and the nervous system, the mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation in cardiac muscle development and function remain unknown. Maintaining contractile function requires the de novo assembly of sarcomeres (i.e., contractile units), and other specialized structural and regulatory complexes. A critical, but unsolved aspect of this highly regulated process is the requirement for RNA-based mechanisms in the local control of gene expression throughout heart development and disease. Here, we identify the first specific mRNA targets of FXR1 and the mechanism(s) by which they are post-transcriptionally regulated in the heart. Phenotypic studies showed prominent alterations in the architecture of the cytoskeletal assemblies involved in cardiac force transmission and generation (desmosomes, costameres, and sarcomeres) in Fxr1 knockout embryonic hearts. Consistent with these findings, we identified dsp (desmoplakin) and tln2 (talin2), as the first in vivo mRNA targets of FXR1 and showthat FXR1 binds these mRNAs directly in their 3′ untranslated regions, functioning to repress translation and control their protein levels in cardiac muscle. Since loss of FXR1 results in cardiomyopathy in zebrafish and neonatal lethality in mice, this work reveals that RNA regulation is a critical process for cardiac function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edouard Khandjian for anti-FXR1 antibodies for initial studies; Paul Krieg for insightful discussion and editing of the manuscript; Chinedu Nworu for sarcomere length assessments; Ruiting Zong for tissue for preliminary experiments; Dan Schnurr for help with in vitro RNA transcription; Tania Yatskievych for embryonic dissections; Tony Day for TEM experiments; and Abigail McElhinny and Katherine Bliss for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by an AHA Predoctoral Fellowship (0910027G) and a NHLBI training grant (T32 HL07249-31) to S. Whitman; the Undergraduate Biology Research Program (HHMI52005889) to L. Yu; an AHA Scientist Development Grant (0930170N) and a Sarver Heart Center Schneider Award to D. Zarnescu; and NIH grants (HL083146) to C. Gregorio and (HD38038) to D. Nelson. An NSF ADVANCE grant provided funding to D. Zarnescu and C. Gregorio to initiate this project.

Abbreviations

- FXR1

Fragile X mental retardation, autosomal homolog 1

- RNA-IP

FXR1 immunoprecipitation with RNA protection and isolation

- E18.5

embryonic day 18.5

- FraX

Fragile X

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Clark KA, McElhinny AS, Beckerle MC, Gregorio CC. Striated muscle cytoarchitecture: an intricate web of form and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:637–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ervasti JM. Costameres: the Achilles’ heel of Herculean muscle. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13591–13594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell B, Curtis MW, Koshman YE, Samarel AM. Mechanical stress-induced sarcomere assembly for cardiac muscle growth in length and width. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2010;48:817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noorman M, van der Heyden MAG, van Veen TAB, Cox MGPJ, Hauer RNW, de Bakker JMT, van Rijen HVM. Cardiac cell-cell junctions in health and disease: Electrical versus mechanical coupling. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2009;47:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang M, Wang Q, Huang Y. Fragile X mental retardation protein FMRP and the RNA export factor NXF2 associate with and destabilize Nxf1 mRNA in neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10057–10062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700169104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zalfa F, Eleuteri B, Dickson KS, Mercaldo V, De Rubeis S, di Penta A, Tabolacci E, Chiurazzi P, Neri G, Grant SG, Bagni C. A new function for the fragile X mental retardation protein in regulation of PSD-95 mRNA stability. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:578–587. doi: 10.1038/nn1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estes PS, O’Shea M, Clasen S, Zarnescu DC. Fragile X protein controls the efficacy of mRNA transport in Drosophila neurons. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2008;39:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X Syndrome: Loss of Local mRNA Regulation Alters Synaptic Development and Function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashley CT, Jr, Wilkinson KD, Reines D, Warren ST. FMR1 protein: conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science. 1993;262:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.7692601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbin F, Bouillon M, Fortin A, Morin S, Rousseau F, Khandjian EW. The fragile X mental retardation protein is associated with poly(A)+ mRNA in actively translating polyribosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1465–1472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khandjian EW, Huot ME, Tremblay S, Davidovic L, Mazroui R, Bardoni B. Biochemical evidence for the association of fragile X mental retardation protein with brain polyribosomal ribonucleoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13357–13362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405398101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siomi MC, Zhang Y, Siomi H, Dreyfuss G. Specific sequences in the fragile X syndrome protein FMR1 and the FXR proteins mediate their binding to 60S ribosomal subunits and the interactions among them. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3825–3832. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bardoni B, Schenck A, Mandel JL. The Fragile X mental retardation protein. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darnell JC, Fraser CE, Mostovetsky O, Darnell RB. Discrimination of common and unique RNA-binding activities among Fragile X mental retardation protein paralogs. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3164–3177. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bontekoe CJM, McIlwain KL, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Yuva-Paylor LA, Nellis A, Willemsen R, Fang Z, Kirkpatrick L, Bakker CE, McAninch R, Cheng NC, Merriweather M, Hoogeveen AT, Nelson D, Paylor R, Oostra BA. Knockout mouse model for Fxr2: a model for mental retardation. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:487–498. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer CM, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Oostra BA, Nelson DL, Paylor R. Exaggerated behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1/Fxr2 double knockout mice reveal a functional genetic interaction between Fragile X-related proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1984–1994. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakker CE, de Diego Otero Y, Bontekoe C, Raghoe P, Luteijn T, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Immunocytochemical and Biochemical Characterization of FMRP, FXR1P, and FXR2P in the Mouse. Experimental Cell Research. 2000;258:162–170. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mientjes EJ, Willemsen R, Kirkpatrick LL, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Verweij M, Reis S, Bardoni B, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra BA, Nelson DL. Fxr1 knockout mice show a striated muscle phenotype: implications for Fxr1p function in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1291–1302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van’t Padje S, Chaudhry B, Severijnen L-A, van der Linde HC, Mientjes EJ, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Reduction in fragile X related 1 protein causes cardiomyopathy and muscular dystrophy in zebrafish. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:2564–2570. doi: 10.1242/jeb.032532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidovic L, Sacconi S, Bechara EG, Delplace S, Allegra M, Desnuelle C, Bardoni B. Alteration of expression of muscle specific isoforms of the fragile X related protein 1 (FXR1P) in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy patients. J Med Genet. 2008;45:679–685. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.060541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mankodi A, Urbinati CR, Yuan Q-P, Moxley RT, Sansone V, Krym M, Henderson D, Schalling M, Swanson MS, Thornton CA. Muscleblind localizes to nuclear foci of aberrant RNA in myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2. Human Molecular Genetics. 2001;10:2165–2170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown V, Jin P, Ceman S, Darnell JC, O’Donnell WT, Tenenbaum SA, Jin X, Feng Y, Wilkinson KD, Keene JD, Darnell RB, Warren ST. Microarray identification of FMRP-associated brain mRNAs and altered mRNA translational profiles in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 2001;107:477–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peritz T, Zeng F, Kannanayakal TJ, Kilk K, Eiriksdottir E, Langel U, Eberwine J. Immunoprecipitation of mRNA-protein complexes. Nat Protocols. 2006;1:577–580. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans TL, Mihailescu MR. Recombinant bacterial expression and purification of human fragile X mental retardation protein isoform 1. Protein Expr Purif. 2010;74:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaeffer C, Bardoni B, Mandel JL, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Moine H. The fragile X mental retardation protein binds specifically to its mRNA via a purine quartet motif. EMBO J. 2001;20:4803–4813. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page SG. Measurements of structural parameters in cardiac muscle. The physiological basis of Starling’s law of the heart: Symposium on the Physiological Basis of Starling’s Law of the Heart held at the Ciba Foundation; London. 11–13th September 1973; Amsterdam; New York: Elsevier: Associated Scientific; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen DG, Kentish JC. The cellular basis of the length-tension relation in cardiac muscle. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1985;17:821–840. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sparrow JC, Schock F. The initial steps of myofibril assembly: integrins pave the way. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:293–298. doi: 10.1038/nrm2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khera TK, Dick AD, Nicholson LB. Fragile X-related protein FXR1 controls post-transcriptional suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumour necrosis factor-alpha production by transforming growth factor-beta1. FEBS Journal. 2010;277:2754–2765. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saffitz JE. Dependence of Electrical Coupling on Mechanical Coupling in Cardiac Myocytes: Insights Gained from Cardiomyopathies Caused by Defects in Cell-Cell Connections. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1047:336–344. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carvajal-Huerta L. Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma with woolly hair and dilated cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998;39:418–421. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uzumcu A, Norgett EE, Dindar A, Uyguner O, Nisli K, Kayserili H, Sahin SE, Dupont E, Severs NJ, Leigh IM, Yuksel-Apak M, Kelsell DP, Wollnik B. Loss of desmoplakin isoform I causes early onset cardiomyopathy and heart failure in a Naxos-like syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z, Bowles NE, Scherer SE, Taylor MD, Kearney DL, Ge S, Nadvoretskiy VV, DeFreitas G, Carabello B, Brandon LI, Godsel LM, Green KJ, Saffitz JE, Li H, Danieli GA, Calkins H, Marcus F, Towbin JA. Desmosomal Dysfunction due to Mutations in Desmoplakin Causes Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2006;99:646–655. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000241482.19382.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bornslaeger EA, Corcoran CM, Stappenbeck TS, Green KJ. Breaking the connection: displacement of the desmosomal plaque protein desmoplakin from cell-cell interfaces disrupts anchorage of intermediate filament bundles and alters intercellular junction assembly. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:985–1001. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen NT, Lo SH. The N-terminal half of talin2 is sufficient for mouse development and survival. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conti FJ, Monkley SJ, Wood MR, Critchley DR, Muller U. Talin 1 and 2 are required for myoblast fusion, sarcomere assembly and the maintenance of myotendinous junctions. Development. 2009;136:3597–3606. doi: 10.1242/dev.035857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts GC, Critchley DR. Structural and biophysical properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Biophys Rev. 2009;1:61–69. doi: 10.1007/s12551-009-0009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderwood DA, Zent R, Grant R, Rees DJG, Hynes RO, Ginsberg MH. The Talin Head Domain Binds to Integrin beta Subunit Cytoplasmic Tails and Regulates Integrin Activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28071–28074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engels B, van’t Padje S, Blonden L, Severijnen L-a, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Characterization of Fxr1 in Danio rerio; a simple vertebrate model to study costamere development. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3329–3338. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huot M-E, Bisson N, Davidovic L, Mazroui R, Labelle Y, Moss T, Khandjian EW. The RNA-binding Protein Fragile X-related 1 Regulates Somite Formation in Xenopus laevis. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4350–4361. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van’t Padje S, Chaudhry B, Severijnen LA, van der Linde HC, Mientjes EJ, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Reduction in fragile X related 1 protein causes cardiomyopathy and muscular dystrophy in zebrafish. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:2564–2570. doi: 10.1242/jeb.032532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siomi MC, Siomi H, Sauer WH, Srinivasan S, Nussbaum RL, Dreyfuss G. FXR1, an autosomal homolog of the fragile X mental retardation gene. EMBO J. 1995;14:2401–2408. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sung YJ, Conti J, Currie JR, Brown WT, Denman RB. RNAs that interact with the fragile X syndrome RNA binding protein FMRP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:973–980. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brauch KM, Karst ML, Herron KJ, de Andrade M, Pellikka PA, Rodeheffer RJ, Michels VV, Olson TM. Mutations in ribonucleic acid binding protein gene cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li D, Morales A, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Norton N, Siegfried JD, Hofmeyer M, Hershberger RE. Identification of novel mutations in RBM20 in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zieseniss A, Schroeder U, Buchmeier S, Schoenenberger CA, van den Heuvel J, Jockusch BM, Illenberger S. Raver1 is an integral component of muscle contractile elements. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:583–594. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ding J-H, Xu X, Yang D, Chu P-H, Dalton ND, Ye Z, Yeakley JM, Cheng H, Xiao R-P, Ross J, Chen J, Fu X-D. Dilated cardiomyopathy caused by tissue-specific ablation of SC35 in the heart. EMBO J. 2004;23:885–896. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baehrecke EH. who encodes a KH RNA binding protein that functions in muscle development. Development. 1997;124:1323–1332. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.