Abstract

Introduction

The Diphyllobothrium genus belongs to the Diphyllobothridea order of tapeworms. Diphyllobothrium spp., which is commonly known as fish tapeworm, is generally transmitted in humans, but also in other species, such as bears, dogs, cats, foxes, and other terrestrial carnivores. Although worldwide in distribution, the original heartland of Diphyllobothrium spp. spreads across Scandinavia, northern Russia, and western Serbia. We report a rare case that occurred in India.

Case presentation

A nine-year-old south Indian girl was brought to the casualty at the Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences with complaints of vomiting and loose stools that had started three days earlier. The vomit did not have a foul smell and contained no blood or mucus, but it did contain undigested food particles. The patient described a history of recurrent abdominal pain. She was a non-vegetarian and said she had a history of eating fish.

Conclusion

The incidence of Diphyllobothrium spp. infection is infrequent in India. Since this is only the fourth reported case in India, and since the previously reported cases also involved observed pediatric patients, we emphasize the need for clinical microbiologists and pediatricians to suspect fish tapeworm infection and recommend epidemiological study of Diphyllobothrium spp. infection.

Introduction

The Diphyllobothrium genus belongs to the Diphyllobothridea order of tapeworms. Diphyllobothrium spp., which are commonly known as fish tapeworms, are generally transmitted to humans [1]. Definitive first and second intermediary hosts of Diphyllobothrium spp. include humans, mammals and birds that eat fish, crustaceans, copepods, and fish. Salmonids, pike, perch, and burbot can act as secondary intermediate hosts of Diphyllobothrium spp. in freshwater ecosystems. Although worldwide in distribution, the original heartland of more frequent Diphyllobothrium spp. of the Diphyllobothridea order of tapeworms are spread across Scandinavia, northern Russia, and western Serbia [2].

Case presentation

A nine-year-old south Indian girl was brought to the casualty at the Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences with complaints of vomiting and loose stools that had started three days earlier. The vomit did not have a foul smell and contained no blood or mucus, but it did contain undigested food particles. The patient described a history of recurrent abdominal pain. She was a non-vegetarian and said she had a history of eating fish. She had had a low-grade continuous fever for three days. Her loose stools were watery in consistency, were not foul smelling, and contained no blood or mucus, and the patient showed no signs of dehydration. She reported no history of similar complaints or any previous hospitalization. A general physical examination revealed the patient to be moderately built and dull looking, with a body temperature of 99°F, a pulse rate of 110 beats per minute, and a respiration rate of 22 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure recorded upon admittance to our hospital was 110/70 mmHg.

The hematological profile of the patient showed 9.3 g/dL hemoglobin, total red blood cell (RBC) count 3.82 RBC/mm3, a low hematocrit level of 27.6% (normal 37% to 47%), a below normal mean corpuscular volume of 72.3 μm3/RBC (normal 82 μm3/RBC to 92 μm3/RBC), a low mean corpuscular hemoglobin volume of 24.3 pg/cell (normal 27 pg/cell to 32 pg/cell), and a mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 33.6% (normal 32% to 36%). No eosinophilia (3%) was observed, and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate was found to be 10 mm per hour.

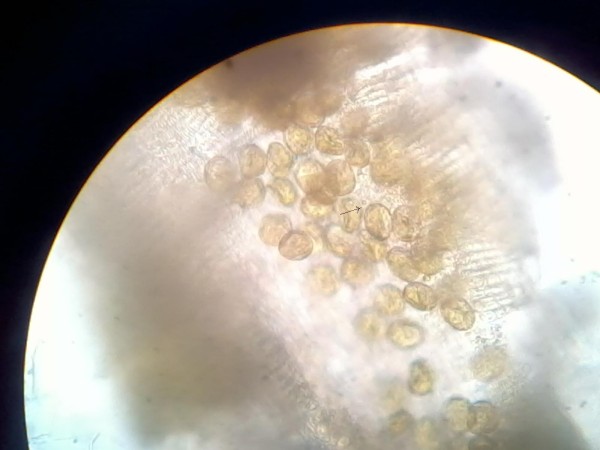

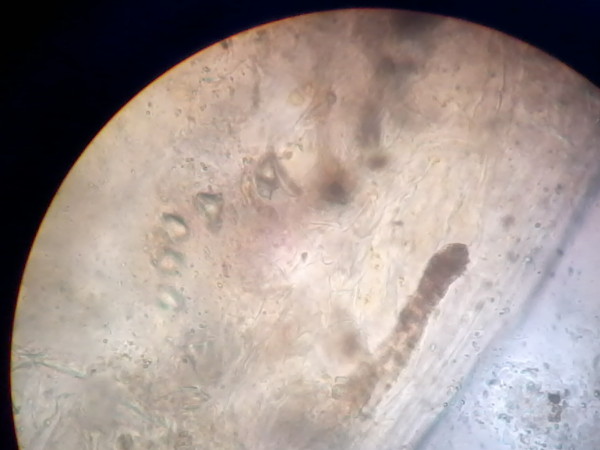

Stool samples obtained for ova and cyst examination were sent to the microbiology laboratory. Simultaneously, blood was sent for culture. Macroscopy of her stool revealed undigested material that was semi-formed but without any foul smell. White to creamish specks were observed in her stool, indicating the probable presence of tapeworms. A wet mount showed the presence of operculated eggs measuring 75 μm×40 μm (Figure 1). Characteristic broader than long segments of tapeworm were observed. On repeated wet mounts, scolex of the tapeworm along with gravid proglottids and a group of eggs were observed (Figure 2). On the basis of the morphology of the eggs with operculum and the presence of broader than long segments, as well as the scolex, the parasite was identified as Diphyllobothrium spp. The patient's blood culture was negative.

Figure 1.

Eggs of Diphyllobothrium spp.

Figure 2.

Adult tapeworm showing scolex and segments.

Discussion

Diphyllobothrium genus belongs to the order Diphyllobothridea. There are six different Diphyllobothrium spp., including Diphyllobothrium latum, Diphyllobothrium dendriticum, Diphyllobothrium klebanowski, Diphyllobothrium cordatum, Diphyllobothrium dalliae, Diphyllobothrium ursi, and Diphyllobothrium nihonkaiense. D. latum, commonly referred to as "fish tapeworm," infects humans [3]. Diphyllobothriasis causes minimal local pathology, but is responsible for reduced vitamin B12 absorption and altered gut mobility [4]. The common symptoms include weakness, dizziness, salt craving, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort. Diphyllobothriasis is associated with eating raw fish and is endemic to Serbia, Scandinavia, North America, Japan, and Chile, with more than 2% prevalence worldwide [2].

Although widespread in distribution, diphyllobothriasis is not often reported in India. Previous reports of fish tapeworm infection in India were from Pondicherry and Vellore, both of which are in southern India [5-7]. No cases in other parts of India have yet been recorded. In contrast to what was observed in previous studies, our patient showed no marked eosinophilia and presented with mild fever [5]. Anemia was established (9.3 g/dL), and the blood smear was normocytic and hypochromic in nature. This suggests that there was no marked vitamin B12 deficiency, which can lead to megaloblastic anemia in individuals infected with fish tapeworm. A detailed review of the previous literature revealed that only three previous cases in India have been reported, and in both cases, the infections were in pediatric patients, in contrast to what has been observed in recent Korean cases of diphyllobothriasis, which involved middle-aged individuals [8].

Conclusion

Our findings suggest the probable undiagnosed parasite manifestation in pediatric patients. We therefore recommend epidemiological studies of fish tapeworm manifestation in pediatric patients, as the infections, if undiagnosed or underreported, can lead to considerable morbidity.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's next-of-kin for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KVR analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the Diphyllobothrium latum infection and performed the parasite identification. KVR and DSR were major contributors in writing the manuscript. BVM, MK, and RR all contributed to writing the manuscript. MSN and KV evaluated the patient clinically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

KV Ramana, Email: ramana_20021@rediffmail.com.

Sanjeev Rao, Email: s_sanrao@yahoo.co.in.

Moses Vinaykumar, Email: ramana20021@gmail.com.

M Krishnappa, Email: ramana20021@yahoo.com.

Rajeshwar Reddy, Email: kasarlarajesh@yahoo.com.

Mohammed Sarfaraz, Email: tejaswani19@gmail.com.

Vamshikrishna Kondle, Email: ramana20021@rediffmail.com.

MS Ratnamani, Email: ratna.sharma@rediffmail.com.

Ratna Rao, Email: ratnarao@hotmail.com.

References

- Von Bondsdorff B. Diphyllobothriasis in Man. London: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- King CH. In: Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 5. Mandell GL, Bennett JB, Dolin R, editor. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. Cestodes (tapeworms). Chapter 285; pp. 2956–2958. [Google Scholar]

- Rausch RL, Scott EM, Rausch VR. Helminths in Eskimos in western Alaska, with particular reference to Diphyllobothrium infection and anaemia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1967;61:351–357. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(67)90008-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baily G Cook GC, Zumla AI. Other cestode infection: intestinal cestodes, cysticercosis, other larval cestode infections Manson's Tropical Diseases 2003Chapter 8521Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 1593–1596.21803989 [Google Scholar]

- Devi CS, Srinivasan S, Murmu UC, Barman P, Kanungo R. A rare case of diphyllobothriasis from Pondicherry, South India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:152–154. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.32725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancharatnam S, Jacob E, Kang G. Human diphyllobothriasis: first report from India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:179–180. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)90737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar CS, Anand Kumar H, Sunita V, Kapur I. Prevalence of anemia and worm infestation in school going girls at Gulbarga, Karnataka. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EB, Song JH, Park NS, Kang BK, Lee HS, Han YJ, Kim HJ, Shin EH, Chai JY. A case of Diphyllobothrium latum infection with a brief review of diphyllobothriasis in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2007;45:219–223. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2007.45.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]