Abstract

Multiple molecular chaperones, including Hsp90 and p23, interact with members of the intracellular receptor (IR) family. To investigate p23 function, we compared the effects of three p23 proteins on IR activities, yeast p23 (sba1p) and the two human p23 homologs, p23 and tsp23. We found that Sba1p was indistinguishable from human p23 in assays of seven IR activities in both animal cells and in yeast; in contrast, certain effects of tsp23 were specific to that homolog. Transcriptional activation by two IRs was increased by expression of any of the p23 species, whereas activation by five other IRs was decreased by Sba1p or p23, and unaffected by tsp23. p23 was expressed in all tissues examined except striated and cardiac muscle, whereas tsp23 accumulated in a complementary pattern; hence, p23 proteins might contribute to tissue-specific differences in IR activities. Unlike Hsp90, which acts on IR aporeceptors to stimulate ligand potency (i.e., hormone-binding affinity), p23 proteins acted on IR holoreceptors to alter ligand efficiencies (i.e., transcriptional activation activity). Moreover, the p23 effects developed slowly, requiring prolonged exposure to hormone. In vitro, p23 interacted preferentially with hormone–receptor–response element ternary complexes, and stimulated receptor–DNA dissociation. The dissociation was reversed by addition of a fragment of the GRIP1 coactivator, suggesting that the two reactions may be in competition in vivo. Our findings suggest that p23 functions at one or more late steps in IR-mediated signal transduction, perhaps including receptor recycling and/or reversal of the response.

Keywords: intracellular receptor, ligand efficacy, molecular chaperone, p23

In vivo, the native states of proteins are reached in part through interactions with molecular chaperones (Hartl 1996; Beissinger and Buchner 1998; Bukau and Horwich 1998). On the basis of in vitro activities and cellular expression levels, the primary molecular chaperones in eukaryotic cytosol are thought to be Hsp90 and Hsp70, together with the chaperone/accessory factors Chaperonin Containing TCP-1 (CCT), Hsp104, HiP, p23, large immunophilins (e.g., cyclophilin-40, FKBP52, and FKBP51), HOP (Hsp90/Hsp70 organizing protein), Hsp40, and Bag-1 (Hartl 1996; Johnson and Craig 1997). Several of these factors are recovered in various complexes (e.g., Hsp90–HOP–Hsp70 or Hsp90–immunophilin) that may serve as functional units.

Assays of molecular chaperone activities in vitro typically measure either prevention of aggregation of a non-native protein or refolding of a substrate protein to a functional conformation (Johnson and Craig 1997). Such assays have generally failed to distinguish the different chaperones, particularly those whose primary activity measured in vitro is suppression of aggregation. Thus, the roles of the individual components in the putative complexes have not been determined.

The best-defined substrates for the molecular chaperones are the intracellular receptors (IRs) (Smith and Toft 1992; Bohen and Yamamoto 1994; Pratt and Toft 1997). IRs are signal transducers that modulate transcription from specific promoters in response to binding cognate hydrophobic ligands such as hormonal steroids (Mangelsdorf et al. 1995). In the absence of hormone, steroid receptors reside in aporeceptor complexes with various molecular chaperones. Upon hormone binding, the receptor–hormone complexes bind tightly to genomic response elements and modulate transcription from nearby promoters (Zaret and Yamamoto 1984). Genetic and biochemical studies have shown that Hsp90 and HOP stimulate ligand potency, increasing the affinity of hormone-binding activity by steroid (Bohen and Yamamoto 1993; Smith et al. 1993; Nathan and Lindquist 1995; Chen et al. 1996; Chang et al. 1997) and retinoid (Holley and Yamamoto 1995) receptors. Hsp70 and Hsp40 may also be involved in establishing the hormone-binding state of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (Dittmar and Pratt 1997). Finally, the large immunophilins and p23 appear to associate with aporeceptor complexes, but their effects on receptor function have been a matter of debate (Duina et al. 1996; Warth et al. 1997; Bohen 1998; Fang et al. 1998).

The Sacchromyces cerevisiae SBA1 gene encodes a protein with 26% amino acid identity to the human p23 protein (Bohen 1998, Fang et al. 1998). Consistent with this similarity, Sba1p associates with Hsp82, a yeast Hsp90 ortholog. A second human homolog, tsp23 (transcript similar p23), displays 44% and 17% amino acid identity, respectively, with p23 and Sba1p (Castilla 1995; L. Brody, pers. comm.). To investigate further the role of p23 in IR function, we examined the effects of these three p23 proteins on the activities of intracellular receptors in vivo and in vitro.

Results

Human p23 homologs have distinct tissue expression patterns

The eukaryotic chaperone families are generally composed of multiple members; for example, the Hsp70 family in S. cerevisiae includes 22 alleles. Particular family members typically reside in distinct intracellular compartments, although compartments may accommodate multiple homologs. The mammalian chaperone families are similarly extensive, but less well defined than those in S. cerevisiae. The physiological roles of these multicomponent gene families are unknown. Conceivably, they define distinct substrate specificities or different actions on a given substrate.

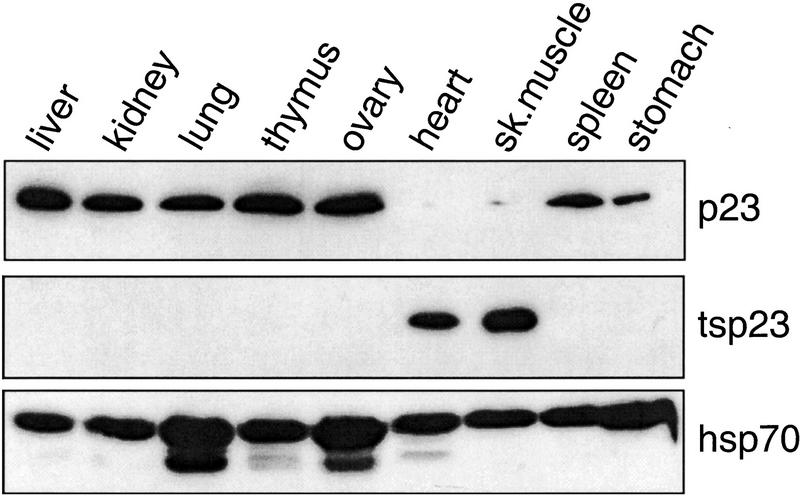

The molecular chaperone p23 was identified as a component of the GR and progesterone (PR) aporeceptor complexes (Hutchison et al. 1995; Johnson and Toft 1995), whereas tsp23 was discovered during a search for the BRCA1 gene (L. Brody, pers. comm.). In adult mice, we found by immunoblotting that p23 accumulated in most tissues with the exception of heart and skeletal muscle, whereas tsp23 was detected primarily in heart and skeletal muscle (Fig. 1). Perhaps notably, p23 and not tsp23 was observed in stomach smooth muscle. In contrast, Hsp70 was ubiquitously expressed at equivalent levels in all tissues examined. Similar expression patterns were found in rat tissues (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Mammalian cells contain p23 homologs with distinct tissue expression patterns. Immunoblot analysis of extracts prepared from indicated Mus musculus tissues. The p23 homologs or Hsp70 were detected with monoclonal antibodies as indicated.

Effects of p23 homologs on receptor activities in mammalian cells

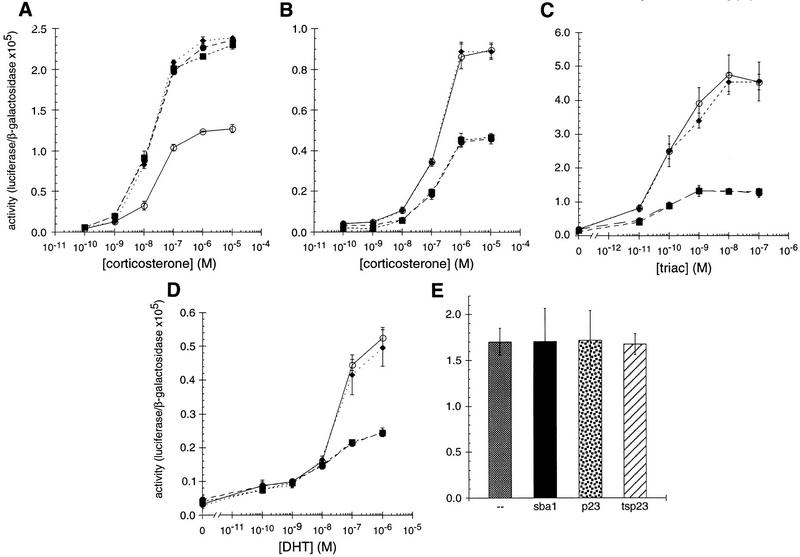

The existence of chaperone homologs with distinct tissue expression patterns opens the possibility that each homolog has unique tissue and cellular activities, perhaps yielding distinguishable actions on similar substrates. To test this hypothesis, we characterized the effects of different p23 homologs on IRs in mammalian cells. Cotransfection of HeLa cells with expression plasmids for GR together with p23, tsp23, or SBA1, increased GR activity by two- to threefold at all hormone levels tested (Fig. 2A). In contrast, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), thyroid hormone receptor (TR), and androgen receptor (AR) activities were decreased two- to threefold by p23 or Sba1p, and unaffected by tsp23 (Fig. 2B, C, D). MR and GR are closely related, and in these assays, they were compared using the same hormone and the same response element. Hence, it was especially striking that the p23 homologs produced significantly different effects on these two receptors, and that p23 and tsp23 were distinguishable on MR. As a control, the p23 homologs had no effect on the activity on an unrelated transcriptional regulator, c-Jun (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

p23 differentially affects the activity of GR, MR, TR, or AR in animal cells. The effects of p23 (●), tsp23 (♦), or Sba1p (█) on (A) GR, (B) MR, (C) TR, or (D) AR was measured in transiently transfected HeLa cells. For comparison, GR, MR, TR, or AR was transfected in the absence of an exogenous p23 homolog (○). (E) As a control, the activity of c-Jun alone or cotransfected with SBA1, p23, or tsp23 was examined.

Differential effects of p23 homologs on IRs in yeast

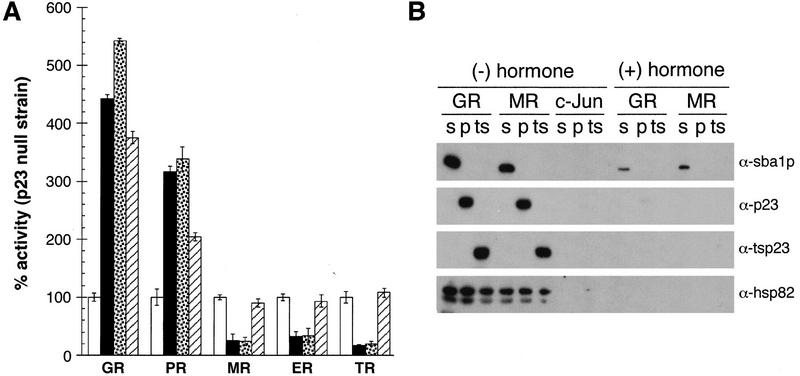

S. cerevisiae provides a heterologous setting in which functional interactions of p23 and IRs can be compared free of the background of endogenous receptors and p23 homologs that reside in mammalian cells. We began with a yeast strain lacking SBA1 (Δp23; Bohen 1998). The activities of five receptors were assessed in the absence of a p23 homolog or upon coexpression of Sba1p, p23, or tsp23. All three p23 species increased GR and PR activities, whereas Sba1p and p23 decreased the activities of the estrogen receptor (ER), MR, and TR; in contrast, tsp23 did not affect ER, MR, and TR (Fig. 3A). These results are consistent with those in mammalian cells and extend the differential effects of p23 homologs to a broader array of receptors.

Figure 3.

p23 homologs interact with IRs and affect their activities. (A) Effects of p23, tsp23, or Sba1p on the transcriptional activities of IRs in S. cerevisiae strain (YNK233; Δp23) bearing a disrupted SBA1 gene. The Δp23 strain carried expression plasmids for GR, PR, MR, ER, or TR and were cotransformed with a LEU2 marker plasmid (open bar) or an expression vector for Sba1p (solid bar), p23 (stippled bar), or tsp23 (hatched bar). All transformants carried a reporter plasmid with the appropriate response elements driving a CYC1–lacz fusion. Data were normalized to the activity of the Δp23 strain carrying the LEU2 marker plasmid and represent the average values from three independent assays; error bars, s.e.m.. (B) Association of Sba1p (s), p23 (p), tsp23 (ts), and Hsp82 with IRs. Following growth in the appropriate selective medium and exposure to 10 μm corticosterone where indicated, cell extracts were prepared by glass-bead homogenization and clarification by centrifugation. The GR, MR, or control protein c-Jun was precipitated from 250 μg of protein extract using antibodies specific for each factor. The reactions were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE, electroblotted to Immobilon-P, and the indicated proteins detected by immunoblotting.

In coimmunoprecipitation studies we recovered each of the three p23 homologs in association with the GR and MR aporeceptors (but not with c-Jun), whereas little or no association was observed with hormone-bound receptors (Fig. 3B); control experiments confirmed that a similar level of each receptor was precipitated under each condition (data not shown). A low level of Sba1p reproducibly remained bound to GR and MR after hormone addition, possibly indicating that p23 proteins might affect both holoreceptors and aporeceptors. As expected from previous reports, Hsp82, the yeast Hsp90 ortholog, also interacted with the GR and MR aporeceptors but not with the holoreceptors (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results imply that p23 may contribute to tissue-specific differences in IR activities.

Effects of the yeast p23 homolog on IR activities

The conservation and ubiquitous expression of p23-like proteins from yeast to mammals support the view that p23 serves as a general chaperone within eukaryotic cells. In human and yeast extracts, p23 associates with Hsp90 (Johnson and Toft 1994; Fang et al. 1998), and IRs serve as substrates for p23 in mammalian cells (Hutchison et al. 1995; Johnson and Toft 1995). Particularly striking was our finding that p23 and Sba1p were indistinguishable in their effects on receptors in mammalian and in yeast cells. To extend these studies in a simple cellular context while maintaining homologous interactions within the chaperone complexes, we therefore focused on Sba1p in yeast and examined further the role of p23 homologs in IR function.

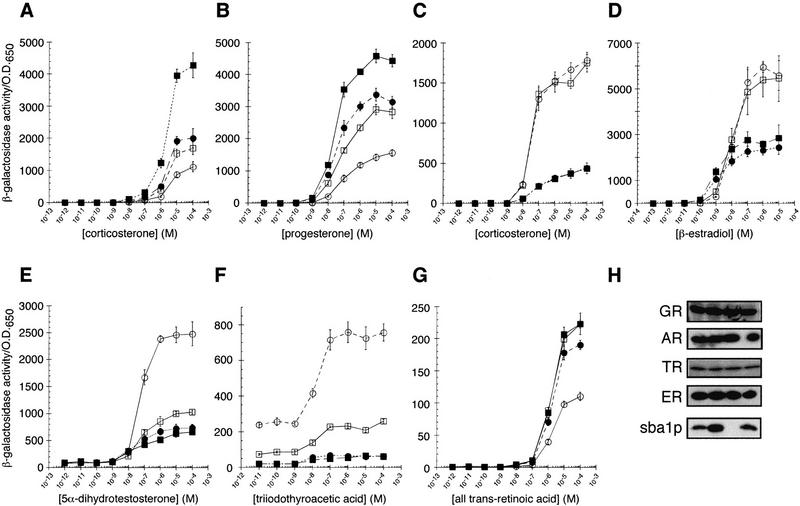

GR and PR activities were approximately twofold lower in Δp23 relative to the parent strain; conversely, GR and PR activities were increased by exogenously introduced Sba1p in both the parent and Δp23 strains (Fig. 4A, B). Immunoblotting confirmed that receptor activities correlated with Sba1p accumulation (ectopic expression yielded an ∼10-fold increase in Sba1p in the parent strain and an ∼4-fold increase in the Δp23 strain relative to endogenous levels) and not with receptor levels per se (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4.

The molecular chaperone p23 differentially alters the activity of intracellular receptors. The dose response behavior of GR (A), PR (B), MR (C), ER (D), AR (E), TR (F), or RAR (G) in the parent (wild-type) and p23 disruption strain (Δp23) with (wild-type █; Δp23 ●) or without (wild-type □; Δp23 ○) plasmid expression of Sba1p. Data represent average values from three independent assays; error bars, s.e.m.. (H) Western blots from yeast extract preparations are shown; sample order is wild type, wild type with plasmid expressing Sba1p, Δp23, and Δp23 with plasmid expressing Sba1p. GR, AR, ER, TR, and Sba1p were detected by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies.

In contrast to our findings with GR and PR, overexpression of Sba1p decreased the activities of MR, ER, AR, and TR (Fig. 4C–F). Disruption of the SBA1 gene did not alter MR and ER activity, whereas TR and AR activities were approximately twofold higher in Δp23 than in the parental strain. Retinoic acid receptor (RAR) activity was not detectably altered by Sba1p overexpression, but was reduced by SBA1 disruption (Fig. 4G).

Strikingly, for all seven receptors tested, Sba1p exerted its effects at the level of ligand efficacy (i.e., maximal transcriptional activation activity). In addition, ligand potency (i.e., hormone binding) was altered for PR (Fig. 4B) and ER (Fig. 4D). It is intriguing that Sba1p increased ligand potency for both receptors, but conferred opposing effects on ligand efficacy. A simple interpretation of these results is that Sba1p influences the conformation of IR transcriptional regulatory domains and that, in the case of ER and PR, those conformational effects alter hormone binding as well as transcriptional regulatory activity; such a result is not surprising, as a transcriptional activation domain resides within the ligand-binding domains of IRs (Brzozowski et al. 1997; Darimont et al. 1998; Shiau et al. 1998). In contrast to the effects of Sba1p on IRs, c-Jun activity was unaffected (data not shown).

Time course of p23 effects on IR activities

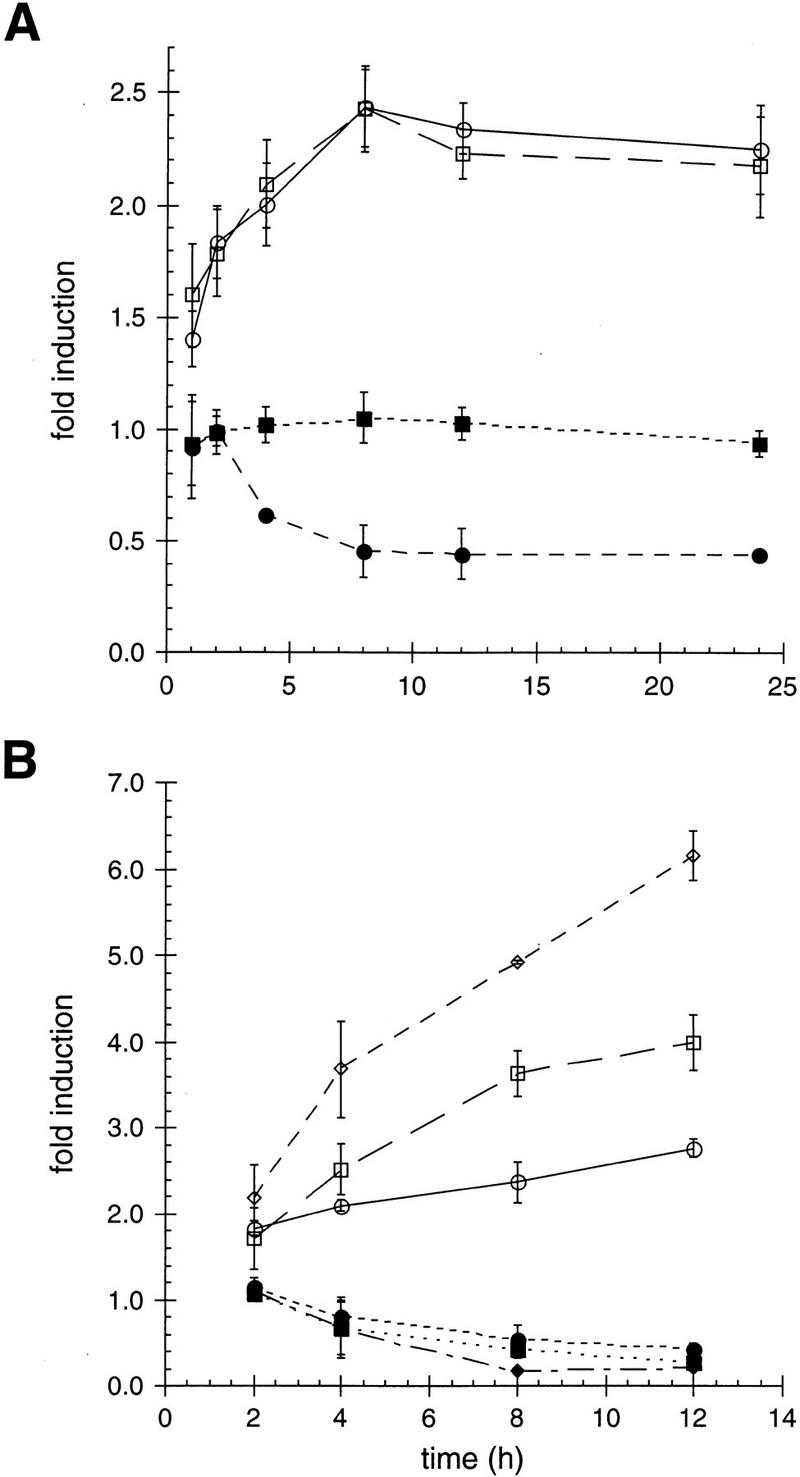

To begin to examine the step in IR action on which the p23 homologs might operate, we measured the time course of their effects in HeLa cells and in yeast. For the mammalian cell studies, we transiently transfected HeLa cell cultures with p23 or tsp23, together with GR or AR and a luciferase-linked reporter gene responsive to either receptor. Twelve hours after transfection, the cultures were treated with agonists (corticosterone or DHT, respectively) for 1–24 hr. Surprisingly, we found that the stimulatory effects of the p23 homologs on GR activity, as well as their inhibitory effects on AR activity, developed with slow kinetics, requiring ∼8 hr to reach equilibrium (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

p23-mediated affects on ligand efficacy for GR and AR occur with slow kinetics in animal and yeast cells. The effect of p23 (circles) or tsp23 (squares), at the indicated time points, on GR (open symbols) or AR (closed symbols) was determined in transiently transfected (A) HeLa cells. The data are presented as the fold change in receptor activity relative to receptor activity in the absence of a cotransfected p23 or tsp23 expression plasmid. The activity of GR (open symbols) or AR (closed symbols) was measured in (B) wild-type yeast (circles), Δp23 expressing exogenous Sba1p (squares), and wild-type expressing exogenous Sba1p (diamonds) at the indicated time points. The data are presented as the fold change in receptor activity relative to receptor activity in the Δp23 strain.

We carried out a parallel study in yeast, measuring the time course with which p23 expression affected receptor activities. For these experiments, we used wild-type or Δp23 strains stably transformed with GR or AR, a β-galactosidase reporter gene, and either with SBA1 or not. Our results for both GR and AR were remarkably similar to those obtained in mammalian cells: The effect of Sba1p expression on receptor activity required ∼8 hr to reach equilibrium (Fig. 5B); the same time course was measured for MR and TR (data not shown).

These results are consistent with our finding that the p23 homologs affect a step in IR action subsequent to hormone binding, which occurs with a t1/2 of ∼5 min in vivo (Baxter and Tomkins 1971), thus presenting the intriguing possibility that the substrate for p23 action may be the hormone-bound holoreceptor (see Discussion).

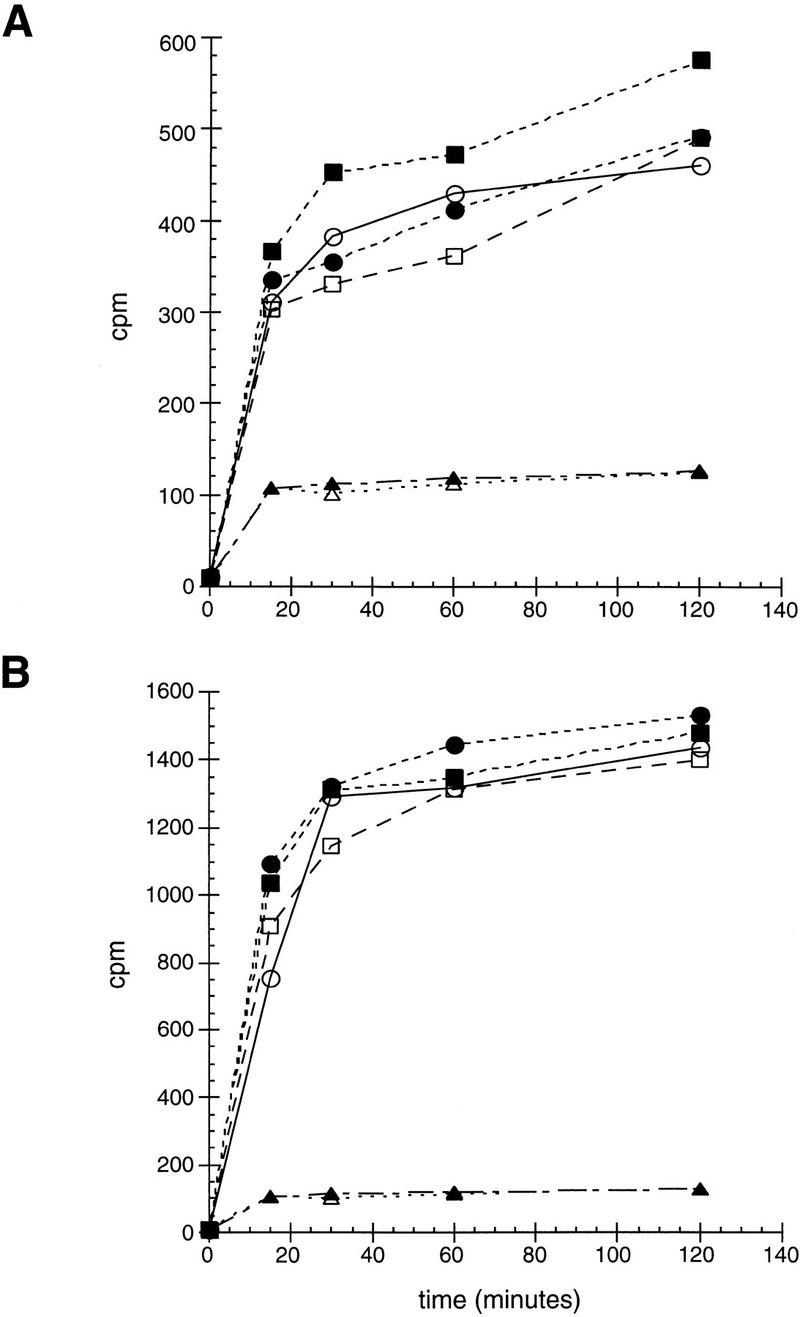

The role of p23 is distinct from the role of Hsp82 with IRs

The Hsp90 molecular chaperone is required for high-affinity hormone binding by IRs (Picard et al. 1990; Hutchison et al. 1992; Bohen and Yamamoto 1993; Holley and Yamamoto 1995; Nathan and Lindquist 1995). We confirmed the effects of the yeast Hsp90 ortholog, Hsp82, on IR activity using several Hsp82 point mutants that are defective in supporting IR activity (Bohen and Yamamoto 1993; Nathan and Lindquist 1995). As shown in Figure 6, the Hsp82 mutants G313N, T525I, or A576T/R579K reduced ligand potency for GR, MR, PR, and AR but had no effect on ligand efficacy. These results contrasted sharply with our finding that the p23 homologs affect IR transcriptional activation activity (i.e., ligand efficacy) in mammalian cells (Fig. 2) and yeast (Fig. 4). As an independent measure of ligand potency, we monitored corticosterone accumulation in yeast strains expressing GR or MR. Strikingly, neither the time course nor the steady state level of hormone accumulation was affected by deletion or overexpression of Sba1p (Fig. 7), supporting the view that p23 proteins do not affect this early step in receptor action. In contrast, various Hsp82 point mutants reduce hormone binding substantially (3- to 25-fold depending on the specific mutant) (Bohen 1995). Thus, unlike p23, aporeceptors are the substrate for the Hsp90 component of the molecular chaperone complex.

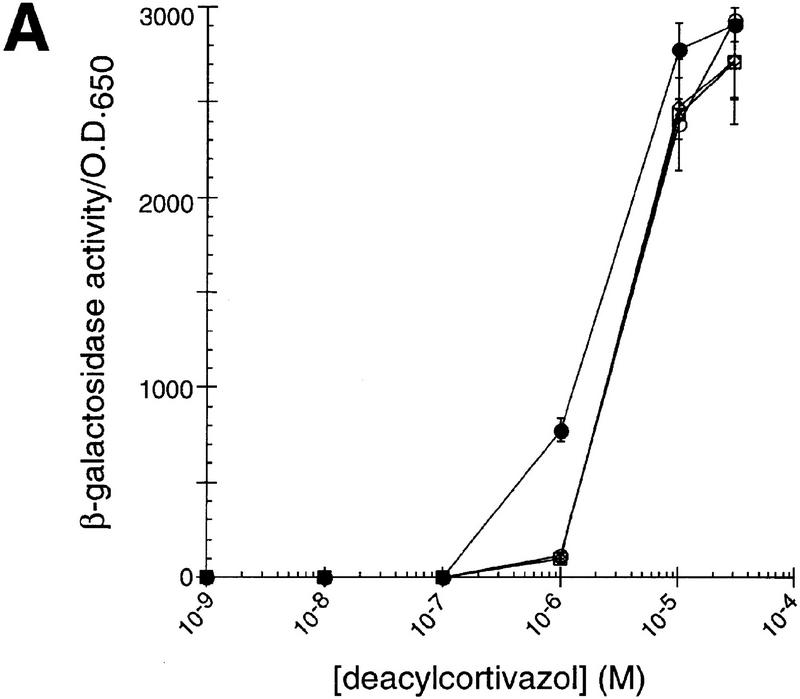

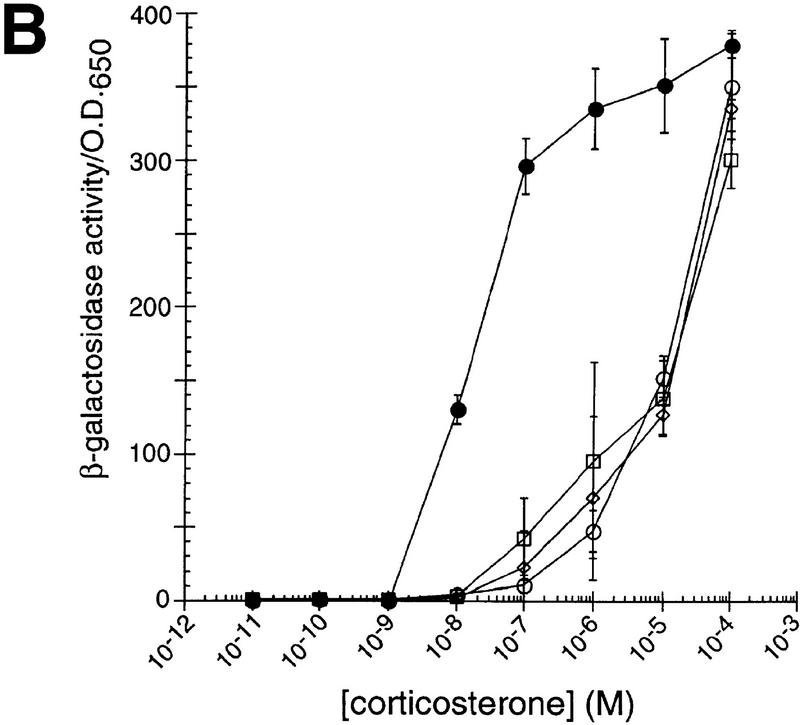

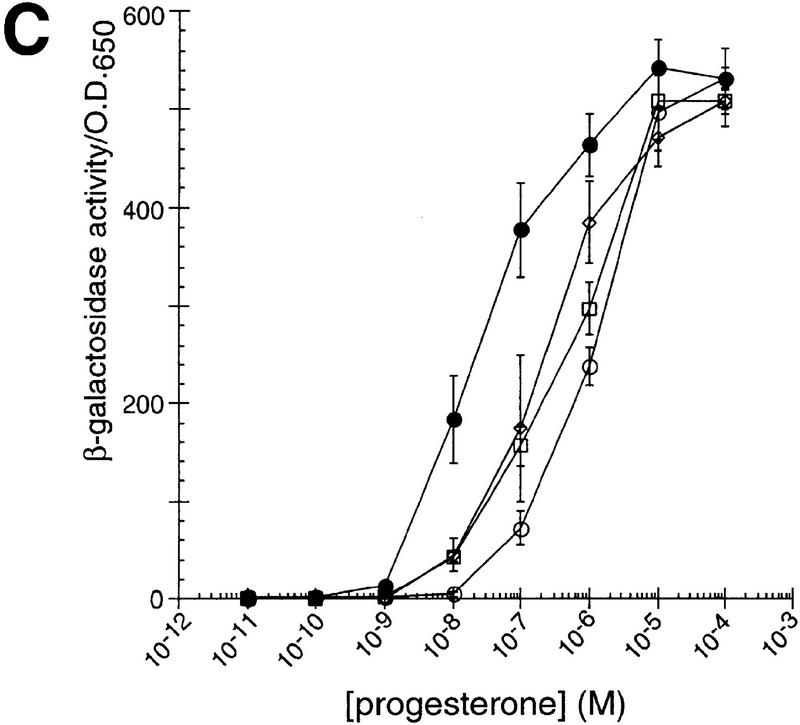

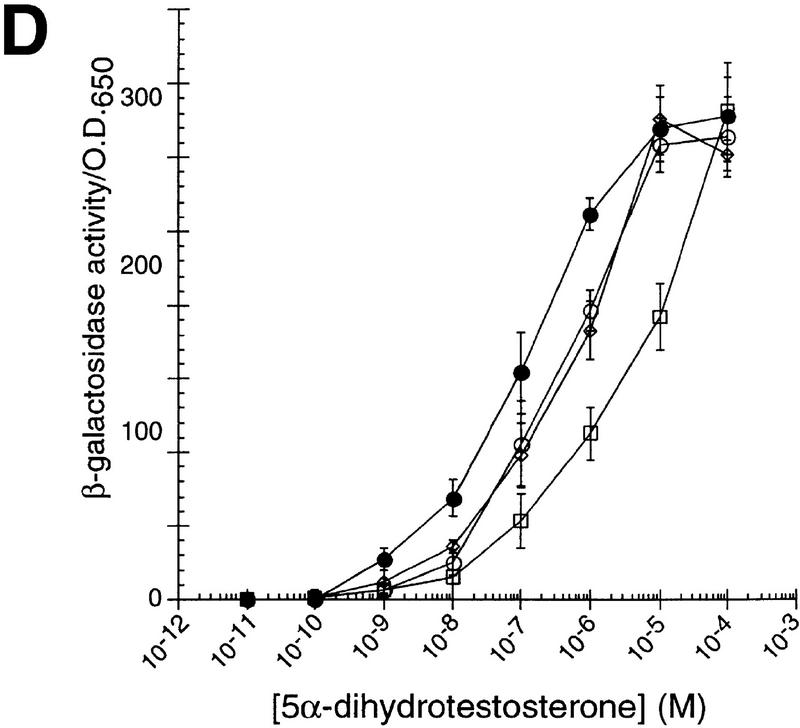

Figure 6.

Point mutations in hsp82 alter ligand potency for intracellular receptors. The activity of GR (A), MR (B), PR (C), and AR (D) was determined in the presence of wild-type Hsp82 (●) or the Hsp82 point mutants G313N (□), T525I (▵), or A576T/R579K (○).

Figure 7.

In vivo hormone accumulation mediated by GR or MR is unaffected by expression levels of Sba1p. Wild-type (squares) or Δp23 (circles) carrying GR (A) or MR (B) expression plasmid, and either a Sba1p expression plasmid (closed markers) or LEU2 marker plasmid (open markers), were exposed to 0.1 μm [3H]corticosterone for the indicated times at 22°C. Following extensive washing, the amount of accumulated [3H]corticosterone was quantified. As a control for nonspecific hormone accumulation, wild-type (▴) and Δp23 (▵) strains not expressing an IR were tested.

Mapping differential sba1p effects on GR and MR

To begin to dissect the mechanism by which p23 proteins exert different effects on the activities of different IRs, we mapped regions of GR and MR that are required for enhancement and inhibition of activity, respectively, by Sba1p. As an initial approach, we tested a series of chimeras (Pearce and Yamamoto 1993) between these two closely related steroid receptors. As shown in Figure 8, the specific effect of Sba1p mapped to the ligand-binding domains (LBDs) of each receptor, which interact with molecular chaperone complexes, bind hormones, and in the presence of hormone associate with coactivator proteins (Darimont et al. 1998) in connection with a transcriptional regulatory function. We found that two chimeras containing the MR LBD were reduced in activity upon overexpression of Sba1p, whereas a chimera containing the GR LBD displayed increased activity.

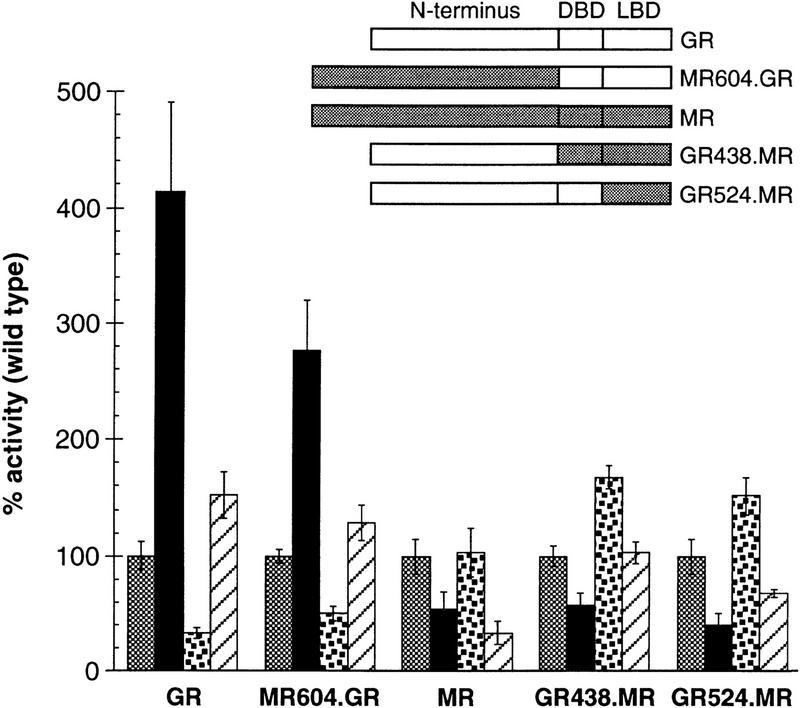

Figure 8.

Sba1p differentially influences the activities GR and MR through the ligand-binding domain. The effect of Sba1p on GR–MR chimeric receptors, in wild-type (shaded bars), wild-type expressing Sba1p from a plasmid (solid bars), Δp23 (stippled bars), or Δp23 expressing Sba1p from a plasmid (hatched bars) was examined. Data for the chimeric receptors were normalized to the activity of the parent strain containing endogenous levels of Sba1p (three independent assays); error bars, s.e.m..

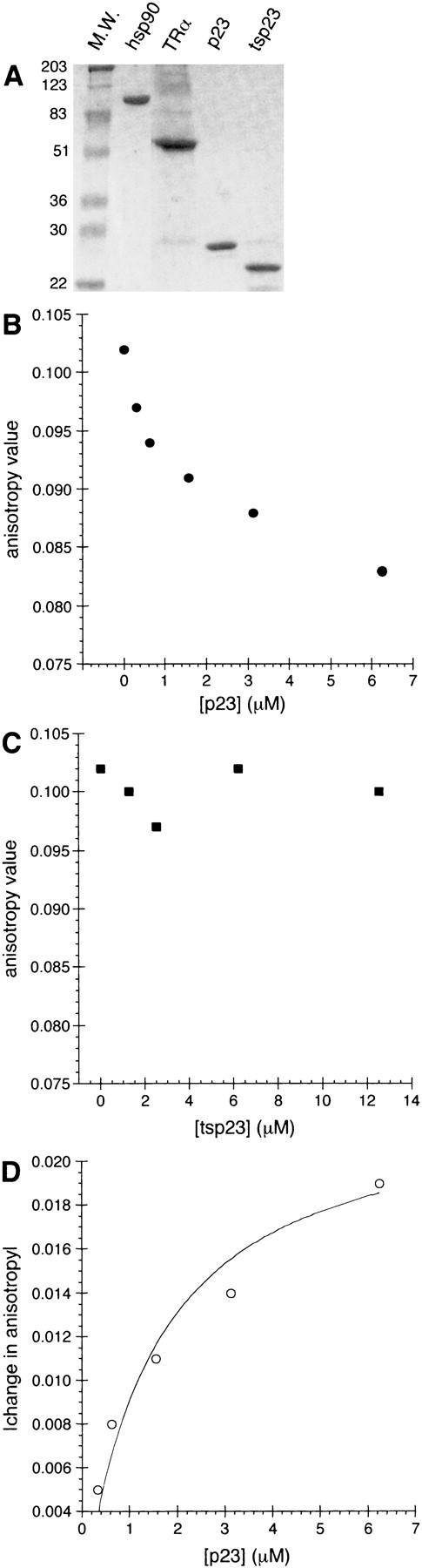

The human p23 homologs differentially dissociate the TR–DNA complex

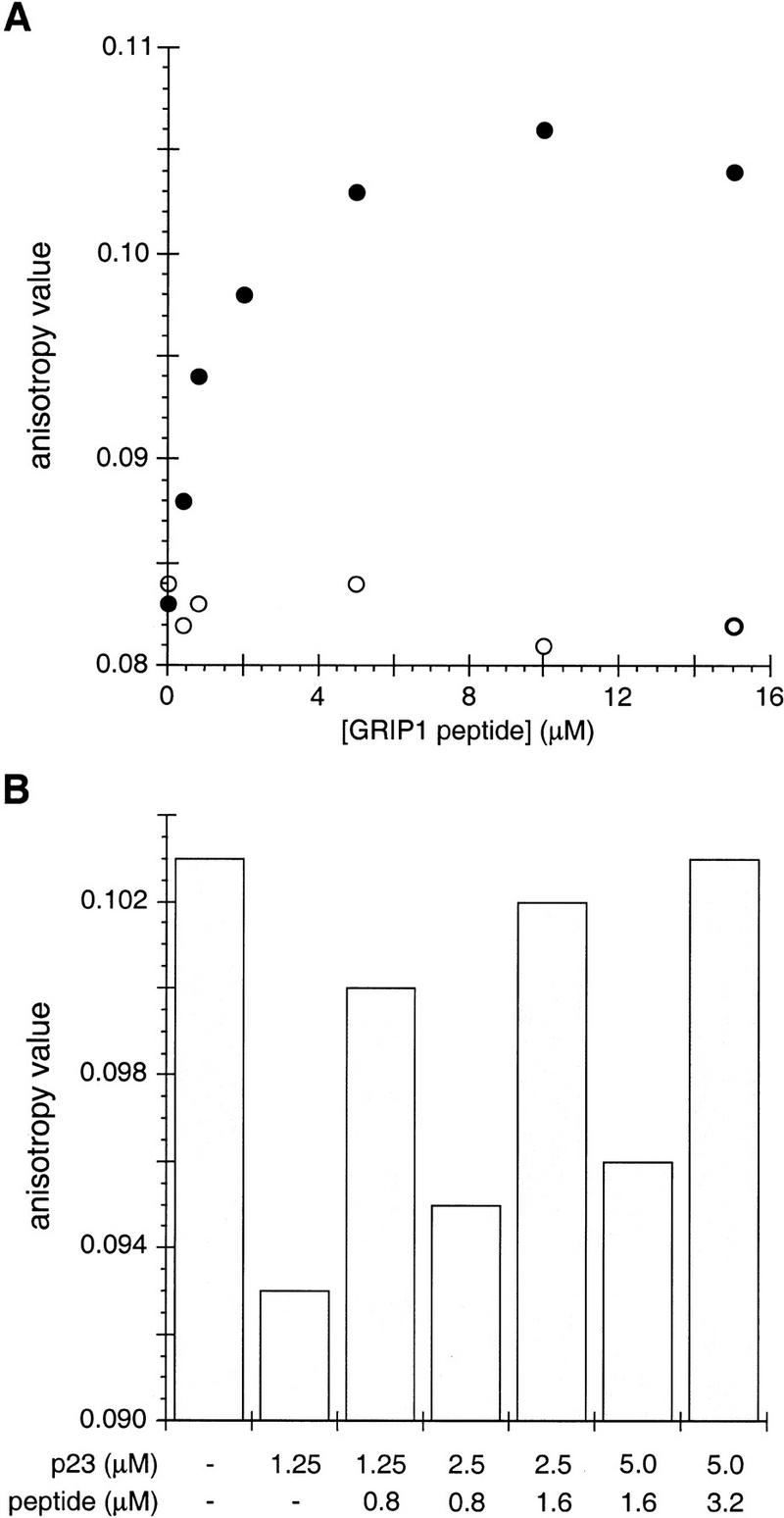

To assess directly the physical and functional interactions of the p23 homologs with a receptor–DNA complex, we purified human p23 and tsp23 to near homogeneity (Fig. 9A) and measured by fluorescence anisotropy their association with purified human TRα bound to fluorescein-tagged DNA. Interestingly, p23 provoked dissociation of the TR–DNA complex, as indicated by the decrease in anisotropy, whereas tsp23 had no effect (Fig. 9B,C).

Figure 9.

p23 inhibits the DNA-binding activity of human TRα in vitro. (A) Purified recombinant (1.5 μg) Hsp90, TRα, p23, and tsp23 visualized by Coomassie blue. Anisotropy values for fluorescein-TREpal oligonucleotide bound by TR upon titration of p23 (B) or tsp23 (C). (D) The disassociation constant (Kd) between TR–p23 was determined by fitting a curve to the absolute value of the change in anisotropy as a function of p23 concentration (see Materials and Methods).

Using the absolute value of the anisotropy change (Fig. 9D), we computed the affinities of the p23–TR interaction under various conditions. In the presence of an agonist ligand (triiodothyroacetic acid; triac) and a thyroid hormone response element (TREpal), the Kd for the interaction between p23 and TR was 1.5 μm, twofold stronger than that measured in the absence of hormone (Table 1). The affinity was lower still when TR was bound to DNA lacking a TRE sequence (C3x1), and hormone had little effect on the p23 interaction with this nonspecific complex (Table 1). We infer that p23 acts stoichiometrically rather than catalytically, as the change in anisotropy was complete in <1 min (data not shown), whereas further p23 addition produced a further decline in anisotropy, eventually approaching that of naked DNA (Fig. 9). When we replaced the full-length TR with an amino-terminal fragment lacking the LBD, we observed no change in anisotropy upon p23 addition (data not shown), implying that the LBD is required for dissociation of the receptor–DNA complex by p23.

Table 1.

Interactions between human TR and p23 or Hsp90

| Protein

|

Response element

|

Kd (μm)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (−) triac

|

(+) triac

|

||

| p23 | TREpal | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| p23 | C3x1 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 4.2 ± 0.4 |

| Hsp90 | TREpal | — | 13.4 ± 1.5 |

In the presence of bound hormone, the TR LBD is bound by coactivator proteins such as GRIP1 and SRC1 (Onate et al. 1995; Hong et al. 1996) through a coactivator segment denoted NR-box 2, which carries an essential LXXLL sequence motif. GRIP1 peptides that encompass the NR-box 2 motif bind the TR LBD with the same affinity as the intact domain (Darimont et al. 1998). We found that an NR-box 2 peptide both prevented and reversed the p23-mediated dissociation of TR from DNA (Fig. 10A). Thus, DNA binding by TR was progressively recovered with titration of increasing levels of the peptide; as a control, a mutant NR-box 2 peptide that fails to interact with TR (Darimont et al. 1998), had no apparent effect on the inhibition of TR's DNA binding activity by p23 (Fig. 10A). To test whether the effects of the wild-type GRIP1 peptide and p23 are in equilibrium, we sequentially added first p23 and then GRIP1 peptide, measuring anisotropy at each step through three such cycles of sequential addition (Fig. 10B). Upon each addition of p23, we observed a decrease in anisotropy, whereas each addition of GRIP1 peptide resulted in an increase in anistropy. These data demonstrate that the effects of p23 and GRIP1 peptide on TR are in equilibrium and that the mechanism by which they occur is stoichiometric as opposed to catalytic.

Figure 10.

The NR-box 2 peptide from GRIP1 prevents and reverses p23-mediated inhibition of the TR–DNA interaction. (A) Wild-type NR-box 2 peptide (●; KHKLHRLLQDSS) or a mutant NR-box 2 peptide (○; KHKLHRAAQDSS) was added at the indicated concentrations into a reaction containing fluorescein-TREpal oligonucleotide, TR and p23 (10 μm), and anisotropy was measured. (B) Aliquots of p23 and NR-box 2 peptide were added sequentially to a reaction mix of fluorescein-TREpal oligonucleotide and TR; anisotropy was measured after each addition.

Liu and DeFranco (1999) reported that inhibition of Hsp90 activity in vivo prevents dissociation of GR from chromatin. Therefore, we repeated our fluorescence anisotropy experiments using Hsp90 rather than p23. We found that Hsp90 did not affect the apoTR–TRE complex. Moreover, although triac–TR could be dissociated from TREpal, the affinity of the Hsp90 interaction was only about one-tenth that measured for p23 (Table 1). Control experiments (data not shown) confirmed that our purified Hsp90 was active, displaying twice the activity of our p23 preparation in a passive chaperone assay measuring suppression of aggregation of denatured β-galactosidase (Freeman et al. 1997).

Discussion

Functional studies of molecular chaperones have been complicated by a scarcity of defined substrates, by relatively crude experimental assays, and by a dearth of genetic approaches. Some progress has been made with Hsp90, however, which has been shown to interact with IRs and to increase their hormone-binding affinities (Bohen and Yamamoto 1993; Holley and Yamamoto 1995; Nathan and Lindquist 1995). Notably, Hsp90 exerts its effects on the earliest steps of receptor action: Hormone binding and nuclear translocation by GR, for example, occur in vivo within minutes of hormone addition (Munck et al. 1972); in Hsp90-deficient backgrounds, both events are abrogated (Bohen and Yamamoto 1993; Nathan and Lindquist 1995).

In this work we demonstrated that the p23 molecular chaperones also influence IR activity. In contrast to Hsp90, however, the p23 proteins affected receptor efficacy (transcriptional activity), operating on one or more late steps in receptor action. Interestingly, the two human homologs, p23 and tsp23, which are expressed in different tissues, affected IR functions differentially: p23 increased the efficacy of certain IRs and decreased that of others, whereas tsp23 conferred stimulatory but not inhibitory effects. The yeast ortholog Sba1p was functionally indistinguishable from the human p23 homolog, both in yeast and animal cells.

Why might p23 homologs differentially affect the transcriptional activities of intracellular receptors? Although the roles of p23 homologs in heart and skeletal muscle are yet to be defined, it is intriguing to speculate that they are influencing TR activity. Perhaps tissues that require robust activity from receptors inhibited by p23 instead express tsp23. For example, TR is involved in cardiac development, and hypothyroidism is linked to changes in heart rate and to coronary heart disease (Slotkin et al. 1992; Klein and Ojamaa 1996; Miura et al. 1996; Wikstrom et al. 1998). In addition, thyroid hormone stimulates production of MyoD, a myogenic transcription factor, in developing muscle (Muscat et al. 1995; Anderson et al. 1998), and induces embryonal carcinoma cells to differentiate into cardiac and striated myocytes (Rodriguez et al. 1994). The presence of distinct p23 homologs within mammalian cells may allow differential activation of IR-responsive genes at a given level of hormone.

It is intriguing that MR and ER activities were decreased upon overexpression of Sba1p, but that disruption of SBA1 had no effect on these receptors. This result may imply the existence of multiple chaperone complexes, including one with a functional homolog of Sba1p that is displaced by overexpressed Sba1p. If Sba1p were less active than its homolog, Sba1p would appear to be a competitive inhibitor, whereas deletion of Sba1p would have no effect. A recent genetic screen indicates that such homologs may exist (B.C. Freeman, unpubl.).

Our work appears to resolve apparent discrepancies in three prior reports on the role of p23 on steroid receptor functions. First, Bohen (1998) failed to observe an effect of Sba1p on GR action. That study, however, used a GR point mutant, F620S, which recently has been discovered to shift GR toward chaperone independence (B.D. Dairmont and K.R. Yamamoto, in prep.). Second, Knoblauch and Garabedian (1999) reported that Sba1p increases ligand potency for ER at subnanomolar estrogen levels. Our findings corroborate that result, and, in addition, demonstrate that Sba1p decreases ligand efficacy (Fig. 4D). Finally, Fang et al. (1998) concluded that AR function, 2 hr following hormone addition, is unaffected by disruption of the SBA1 gene. Our results confirm that finding, and extend it by showing that the effect of Sba1p emerges at later times (Fig. 5).

The effects of p23 on IR function, whether positive or negative, were remarkably slow, requiring 8 hr or longer to reach equilibrium (Fig. 5). This finding was unexpected, as the known steps in IR action occur relatively rapidly. These include association of newly formed hormone–receptor complexes with response elements (t1/2 ∼7 min) (Zaret and Yamamoto 1984), as well as the events of receptor recycling, hormone–receptor dissociation (t1/2 ∼10 min) (Munck and Foley 1976), shutoff of induction upon hormone withdrawal (Reik et al. 1991), and reinduction upon readministration of hormone (Shepherd et al. 1980; Zaret and Yamamoto 1984). Thus, the slow kinetics of p23 action reveal a previously unrecognized late step in IR action. Formally, the p23 effect could be indirect, operating on a gene product induced by the receptor. Strikingly, however, the same time course is observed in yeast and in animal cells. As yeast lacks endogenous IRs, it is highly unlikely that multiple mammalian IRs, introduced exogenously into yeast, would induce yeast genes analogous to those in animal cells. Thus, we suggest the p23 homologs are acting directly on the IRs to influence their transcriptional activation activities.

What might be the new step in IR action that accounts for the slow time course? We speculate that p23 may act upon a special subset of holoreceptors, which we term experienced receptors, that is, holoreceptors that have bound at a response element and regulated transcription, compared with holoreceptors that briefly and nonproductively contact nonspecific DNA before undergoing recycling. Our fluorescence anisotropy studies indicate that holoreceptor–response element ternary complexes are slightly favored substrates for interaction by p23 in vitro (Table 1). In vivo, these ternary complexes may present as distinct targets for p23 because of allosteric effects imposed on the receptor by response elements (Lefstin and Yamamoto 1998), or because of contributions from components of the transcription initiation machinery. According to this scheme, then, p23 would alter the activities of experienced receptors, increasing or decreasing their efficacies; the gradual accumulation of such altered experienced receptors in cells chronically exposed to hormone would account for the slow kinetics of p23 action.

In addition to these observed effects of p23 on receptor activities in vivo, we discovered that p23 displays a striking effect on receptor–DNA interactions in vitro. Although we have not yet defined the affected receptor activity in vivo, this in vitro effect may prove relevant. Other possibilities, not mutually exclusive, include p23-mediated changes in the conformation of transcriptional regulatory domains, or p23 effects on hormone release. In any case, our present view is that different components of one or more heterotypic molecular chaperone complexes act in concert to affect different stages in the pathway of IR action. Thus, whereas Hsp90 operates selectively upon aporeceptors at an early step, p23 acts late by preferentially targeting holoreceptor–response element ternary complexes (Table 1). Our failure to observe a stable interaction between p23 and hormone–receptor binary complexes (Fig. 3) may underscore the importance of response elements or transcription factors in creating experienced receptors that are good substrates for p23. In vitro, the p23 interaction with the TR–DNA complex was influenced by hormone, and the TR LBD was required for p23-mediated dissociation of the TR–DNA complex. Both of these observations imply that p23 interacts with the LBD, consistent with prior studies (Pratt and Toft 1997).

The dynamics of hormone release and receptor recycling are not well understood. However, it seems that both processes must be rapid and continuous, as changes in hormone levels in vivo are efficiently accommodated. There is evidence for efficient recycling in vivo (Baxter and Tomkins 1971; Munck et al. 1972; Rousseau et al. 1973). Our finding that p23 alters the dissociation rate of holoreceptor–response element complexes in vitro may reflect its participation in this process. Once bound, p23, perhaps together with Hsp90 or other members of the chaperone family, may facilitate efficient release of bound hormone and rapid recycling of IRs from response element-bound complexes into aporeceptors that can rebind hormone. The ability of the GRIP1 coactivator peptide to alleviate the inhibitory effects of p23 on the DNA-binding activity of TR is consistent with a role for p23 in receptor recycling or in hormone release (Fig. 10). Thus, p23 and coactivators may compete for association with experienced TR in vivo, affecting hormone and DNA-binding activities of the receptor.

We emphasize that our schemes derive from a well-defined, but narrow perspective. Our goal was to examine the effects of p23 on the single best-characterized family of substrates, the intracellular receptors. IRs are not the only substrates for p23; Sba1p is likely to affect endogenous yeast substrates, for example, and yeast lack IRs entirely. Our model provides an initial conceptual framework on the basis of known substrates; we anticipate that it will require revision as additional substrates are identified and examined. In this context, it will be interesting to investigate other targets of p23, to compare p23 functions with those of other chaperones, and to pursue the mechanisms by which p23 and tsp23 differentially affect their substrates.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

Mammalian transfection assays used expression constructs for rat GR (p6RGR; Godowski et al. 1988), rat MR (p6RMR; Pearce and Yamamoto 1993), human AR (p6RAR; M.I. Diamond and K.R. Yamamoto, unpubl.), and human TR (pSG5-hTRβ; Sharif and Privalsky 1991). The Sba1p expression vector p6Rsba1, the p23 expression vector p6Rp23, the tsp23 expression vector p6Rtsp23, and the β-galactosidase control vector p6Rβ-gal (Pearce and Yamamoto 1993). These plasmids are SP65-based vectors in which the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter is used to drive expression of the respective genes. The luciferase reporter vector pΔ(TAT)3DLO (Vivanco et al. 1995) contains three tandem GREs derived from the tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) GRE (Jantzen et al. 1987) located upstream of the minimal alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) promoter.

The yeast expression constructs for yeast Hsp82 (pHCA–Hsp82), and the yeast Hsp82 point mutants E431K (pHCA–E431K), G313N (pHCA–G313N), T525I (pHCA–T525I), and A576T/R579K (pHCA–A576T/R579K) have been described previously (Bohen and Yamamoto 1993). The yeast expression constructs for rat GR (pTCA–N795), rat MR (pTCA–rMR), human ER (pH2–hERα), human PR (YEp–hPRβ), mouse RAR (pG1–mRARβ), human AR (pG1–hAR), and human TR (pG1–hTRα) and reporter plasmids (pΔs26x, pΔs26x, pΔsERE, pΔs26x, pΔsDR5, pΔs26x, and pΔs2xTREpal, respectively) also have all been described previously (Sharif and Privalsky 1991; Bohen and Yamamoto 1993; Caplan et al. 1995; Holley and Yamamoto 1995). All expression vectors for IRs contained the TRP1 gene as a selection marker. The CEN/ARS plasmids pTCA–N795 and pTCA–rMR express wild-type GR and MR, respectively, from the constitutive yeast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter. The 2μ plasmids pG1–hERα, pG1–mRARβ, pG1–hAR, and pG1–hTRα express the wild-type receptors from the constitutive yeast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter. The 2μ plasmid YEp–hPRβ expresses the wild-type PR from the CUP1 promoter. The 2μ reporter plasmids contain the URA3 gene as a selection marker and a minimal CYC1 promoter linked to three tandem GREs derived from the TAT GRE (pΔs26x), a single estrogen response element (pΔsERE), a single five-space direct repeat (pΔsDR5), or two copies of the palindromic thyroid hormone response element (pΔs2xTREpal).

The yeast expression vector for Sba1p, pRS425–Sba1, was constructed by fusing the SBA1 gene, lacking the FLAG epitope, from a previously described construct (pRS425–Sba1tag; Bohen 1998) to the constitutive yeast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter in the pRS425 backbone (2μ, LEU2). The expression vector for p23, pRS425–p23, has been described (Bohen 1998). The expression vector for tsp23, pRS425–tsp23, was prepared by PCR amplification from the pGEM–tsp23 construct (D.O. Toft, unpubl.); the primer sequences were 5′-TTGTTGGATCCATGGCACGGCAGCACGC-3′ and 5′-TTGTTTCTAGATTAATTACTTGTTGCATCATCA-3′. The amplified fragment was subcloned as a BamHI–XbaI fragment behind the constitutive yeast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter into the pRS425 (2μ, LEU2) backbone as an EcoRI–BamHI fragment.

Antibodies

p23 was detected with monoclonal antibody JJ3 (Johnson and Toft 1994); tsp23 was detected with mAb α-tsp23 2A (S.J. Felts and D.O. Toft, Mayo Clinic); Hsp70 was detected with mAb 3A3 (gift of R.I. Morimoto, Northwestern University, Evanston, Il); GR was detected with mAb sc-1002 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); MR was detected with mAb MA1-620 (Affinity Bioreagents); c-Jun was detected with mAb sc-7481 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); AR was detected with sc-815 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); ER was detected with PA1-310 (Affinity BioReagents); TR was detected with sc-712 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Sba1p was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against recombinant Sba1p (α-Sba1p) (B.C. Freeman and K.R. Yamamoto, unpubl.). The Hsp82 was identified using a polyclonal antibody prepared to human Hsp90 (α-Hsp90/Hsp82) (generously provided by R.I. Morimoto).

Tissue and cell extracts

Extracts from the indicated Mus musculus tissues were prepared from quick-frozen tissue samples from four separate specimens by homogenization in extract buffer [20 mm Tris (pH 6.9), 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm PMSF, 10 mm DTT] and clarified by centrifugation at 25,000g for 45 min at 4°C. Extracts from S. cerevisiae cultures were prepared by glass bead homogenization in extraction buffer supplemented with pepstatin A (2 μg/ml), aprotinin (1 μg/ml), leupeptin (2 μg/ml), and clarified by centrifugation at 25,000g for 45 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad assay using the manufacturer's protocol and BSA as a standard.

Immunoblot analysis

Following fractionation by 12% SDS-PAGE, samples were electroblotted to Immobilon-P membrane. Prior to incubation with the primary antibody, the membranes were incubated in TBS containing 5% non-fat dry milk. Primary antibodies were prepared in TBS supplemented with 5% BSA. Mouse p23 was detected with mAbJJ3 (1:5000), mouse tsp23 was detected with α-mAbtsp23 2A (1:5000), mouse Hsp70 was detected with mAb3A3 (1:10000), rat GR was detected with sc-1002 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), human AR was detected with sc-815 (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), human ER was detected with PA1-310 (1:1000; Affinity BioReagents), and human TR was detected with sc-712 (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Following incubation with the primary antibody, membranes were incubated with secondary (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin) antibody (1:10000 or 1:3000, respectively; Bio-Rad). Membrane washing was carried out in TBS containing 0.2% Tween 20. Protein-antibody complexes were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence immunoblotting detection system according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Pierce).

Mammalian cells, transfections, and reporter assay

HeLa cells, growing on 24-well plates in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM H16) with 10% charcoal-treated fetal calf serum (100 ml of serum was mixed with 2 grams of acid-washed charcoal for 120 min at 22°C and then sterile filtered) were transfected with 50 or 100 ng of p6RGR or p6RMR, respectively, and 100 ng of either p6Rsba1p, p6Rp23, or p6Rtsp23 by lipid-mediated transfection (Hong et al. 1997). In addition to the listed expression plasmids, all transfections included 50 ng of the reporter plasmid pΔDLO and 100 ng of the p6Rβ-gal control plasmid. After 12 hr, the cells were incubated in fresh DMEM supplemented with 10 μm corticosterone (Sigma); following an additional 24 hr incubation, cells were harvested. For extract preparation, PBS washed cells were lysed (1 hr at 25°C) in 100 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity was determined and normalized to β-galactosidase activity as described previously (Iniguez-Lluhi et al. 1997).

Yeast strains

The parent strain used in this work is YNK100 (MATα, pdr5-101; Kralli et al. 1995) and the SBA1-disrupted strain is YNK233 (MATα, pdr5-101, sba1::HIS3; Bohen 1998). The yeast p23 gene is denoted YKL117w (Dujon et al. 1994) under GenBank accession no. Z28117. The YBD100 (MATα, pdr5::TAT3lacZ, hsc82::URA3, gal1-hsp82–LEU2) strain was used to examine the effects of wild-type Hsp82 and the Hsp82 point mutants (B.D. Darimont and K.R. Yamamoto, in prep.). Yeast strains were grown in minimal medium with amino acids and 2% glucose. Plasmid selection was maintained by culturing in medium lacking the appropriate amino acid(s).

Immunoprecipitation assay

The YNK233 strain was transformed by a standard lithium acetate protocol (Gietz et al. 1995) with either pTCA–N795, pTCA–rMR, or pRS313–cJun along with one of the following: pRS425, pRS425–Sba1, pRS425–p23, or pRS425–tsp23. Transformants were grown to saturation in the appropriate selective medium at 22°C. Cultures were diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, grown to an OD600 of 0.8, split into equal volumes; one part was supplemented with 1 μm corticosterone, and the other received an equivalent volume (0.1%) of vehicle (ethanol). The cultures were incubated for an additional 4 hr at 22°C and whole cell extracts were prepared. Following clarification, 500 μg of extract protein was used for precipitation of GR, MR, or c-Jun using antibodies sc-1002, MA1-620, or sc-7481, respectively. Following precipitation, one-half of each reaction was resolved on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred to Immobilon-P membrane, and visualized by immunoblotting.

Yeast reporter assay

The β-galactosidase assay used to report transcriptional activities of IRs in yeast has been described previously (Iniguez-Lluhi et al. 1997). In brief, the yeast cultures were grown to saturation in the appropriate glucose (2%) selective medium in 96-well microtiter plates under constant agitation at 22°C. Cultures were diluted 1:20 into fresh medium supplemented with the indicated hormone (Sigma) and grown for an additional 12 hr except where noted. Cell density was determined as absorbance at 650 nm. Cells were permeabilized in microtiter plates by mixing 10 μl of each culture with an equal volume of 2× reaction buffer [120 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 10 mm KCl, 1 mm MgSO4, and 20 mm β-mercaptoethanol] supplemented with 5% CHAPS and incubated 20 min at 22°C under constant agitation. For the 2- and 4-hr hormone exposure time point, the entire 200-μl culture was clarified and the cell pellet was reconstituted in 20 μl of 1× reaction buffer. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 180 μl of 0.5 mm chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside (Boehringer Mannheim) in 1× reaction buffer prewarmed at 37°C. Progress of the reaction was monitored at 37°C in a temperature-controlled microplate reader (Molecular Devices) by measuring the difference of the absorbance at 550 nm (test) and 650 nm (reference) at 2-min intervals. Activity units are defined as the rate of change in absorbance between 550 and 650 nm, multiplied by the volume of culture used to determine OD650 (e.g., 200 μl), divided by the product of the volume of culture used for the assay (e.g., 10 μl) and the OD650 of the cell culture.

In vivo hormone accumulation assay

The in vivo hormone accumulation assays were as described by Egner et al. (1998). Duplicate cultures were grown to saturation in the appropriate glucose (2%) selective medium, cultures were diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, grown to OD600 of 1.5, 0.1 μm corticosterone supplemented with 106 dpm of [3H]corticosterone (42 Ci/mmole; 1 Ci = 37 GBq; Amersham) was added, and the cultures were incubated for the indicated times. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation (12,000g for 5 min at 4°C), washed three times with cold PBS containing 2% (wt/vol) glucose and 10 μm corticosterone, resuspended in 50 μl of PBS, and the amount of bound hormone was determined by liquid scintillation (Safety-Solve, Research Products International).

Protein purification

Human Hsp90 and triiodothyroacetic acid (triac) were expressed in Sf9 cells with previously described baculovirus strains and human p23 and tsp23 were both expressed in Eschericia coli using pET expression constructs (Fondell et al. 1996; Freeman and Morimoto 1996). Hsp90 and p23 were purified according to protocols published previously (Freeman et al. 1997), tsp23 was purified in a manner similar to p23, and TRα was purified according to Fondell et al. 1996.

Fluorescence anisotropy

The fluorescence anistropy measurements were determined with 125 nm TRα in 10 mm Tris (pH 7.2) 50 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, and 5% glycerol supplemented with 10 μm triac where indicated. The DNA oligonucleotides (100 nm) have fluorscein at the 5′ termini and were the following sequences: TREpal is 5′-TGGGATCCATCTCAGGTCATGACCTGAGATC-3′ (Sharif and Privalsky 1991) and C3x1 is 5′-TCGACCTTGAGAACATCACGTACTATGTAAGCT-3′. The samples were excited at a wavelength of 485 nm, and the emission was monitored at 520 nm in an α-scan (Photon Technologies International). The Kd values were determined by fitting a curve to the absolute value in the change of the anisotropy versus the corresponding concentration of chaperone added; concentrations ranged from 0.312 to 25 μm. The equation used to fit a curve to the data was ({(m1 + 0.1 + m0) − [(m1 + 0.1 + m0) ^ 2–4 × 0.1 × m0] ^ 0.5}/(2 × 0.1)) × m2, where m1 is the calculated Kd, and m2 is the maximal change in anisotropy, which is set for each experiment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawerence Brody (NIH) for supplying a construct with the tsp23 gene, Sean Bohen for other constructs and strains, Richard Morimoto for antibodies to Hsp70 and Hsp90, and the members of the Yamamoto laboratory for discussion and assistance. We also appreciate helpful comments on the manuscript by D. Agard, M. Cronin, R. Derynck, I. Rogatsky, D. Julius, R. Nissen, A. Shiau, and J. Weissman. B.C.F. was supported by fellowships from the Leukemia Research Foundation and the Leukemia Society of America. Research support was from the National Science Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL yamamoto@socrates.ucsf.edu; FAX (415) 476-6129.

References

- Anderson JE, McIntosh LM, Moor AN, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Levels of MyoD protein expression following injury of mdx and normal limb muscle are modified by thyroid hormone. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:59–67. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter JD, Tomkins GM. Specific cytoplasmic glucocorticoid hormone receptors in hepatoma tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1971;68:932–937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.5.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissinger M, Buchner J. How chaperones fold proteins. Biol Chem. 1998;379:245–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohen SP. Hsp90 mutants disrupt glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding and destabilize aporeceptor complexes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29433–29438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Genetic and biochemical analysis of p23 and ansamycin antibiotics in the function of Hsp90-dependent signaling proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3330–3339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohen SP, Yamamoto KR. Isolation of Hsp90 mutants by screening for decreased steroid receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:11424–11428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— . In: Modulation of steroid receptor signal transduction by heat shock proteins. Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C, editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. pp. 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AJ, Langley E, Wilson EM, Vidal J. Hormone-dependent transactivation by the human androgen receptor is regulated by a dnaJ protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5251–5257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilla LH. “Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and the BRCA1 gene.” Ph.D. thesis. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chang HCJ, Nathan DF, Lindquist S. In vivo analysis of the Hsp90 cochaperone Sti1 (p60) Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:318–325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Praparpanich V, Rimerman RA, Honore B, Smith DF. Interactions of p60, a mediator of progesterone receptor assembly, with heat shock proteins Hsp90 and Hsp70. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:682–693. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.6.8776728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darimont BD, Wagner RL, Apriletti JW, Stallcup MR, Kushner PJ, Baxter JD, Fletterick RJ, Yamamoto KR. Structure and specificity of nuclear receptor-coactivator interactions. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3343–3356. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Pratt WB. Folding of the glucocorticoid receptor by the reconstituted hsp90-based chaperone machinery—the initial hsp90-p60-hsp70-dependent step is sufficient for creating the steroid binding conformation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13047–13054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duina AA, Chang HCJ, Marsh JA, Lindquist S, Gaber RF. A cyclophilin function in Hsp90-dependent signal transduction. Science. 1996;274:1713–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B, Alexandraki D, Andre B, Ansorge W, Baladron V, Ballesta JP, Banrevi A, Bolle PA, Bolotin-Fukuhara M, Bossier P. Complete DNA sequence of yeast chromosome XI. Nature. 1994;369:371–378. doi: 10.1038/369371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner R, Rosenthal FE, Kralli A, Sanglard D, Kuchler K. Genetic separation of FK506 susceptibility and drug transport in the yeast Pdr5 ATP-binding cassette multidrug resistance transporter. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:523–543. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Fliss AE, Rao J, Caplan AJ. SBA1 encodes a yeast Hsp90 co-chaperone that is homologous to vertebrate p23 proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3727–3734. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondell JD, Ge H, Roeder RG. Ligand induction of a transcriptionally active thyroid hormone receptor coactivator complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:8329–8333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BC, Morimoto RI. The human cytosolic molecular chaperones hsp90, hsp70 (hsc70) and hdj-1 have distinct roles in recognition of a non-native protein and protein refolding. EMBO J. 1996;15:2969–2979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BC, Toft DO, Morimoto RI. Molecular chaperone machines: Chaperone activities of the cyclophilin Cyp-40 and the steroid aporeceptor-associated protein p23. Science. 1997;274:1718–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Schiestl RH, Willems AR, Woods RA. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godowski PJ, Picard D, Yamamoto KR. Signal transduction and transcriptional regulation by glucocorticoid receptor-LexA fusion proteins. Science. 1988;241:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.3043662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley SJ, Yamamoto KR. A role for Hsp90 in retinoid receptor signal transduction. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1833–1842. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, Kohli K, Triverdi A, Johnson DL, Stallcup MR. GRIP1, a novel mouse protein that serves as a transcriptional co-activator in yeast for the hormone binding domains of steroid receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:4948–4952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K, Zheng W, Baker A, Papahadjopoulos D. Stabilization of cationic liposome-plasmid DNA complexes by polyamines and poly(ethylene glycol)-phospholipid conjugates for efficient in vivo gene delivery. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:233–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KA, Czar MJ, Pratt WB. Evidence that the hormone-binding domain of the mouse glucocorticoid receptor directly represses DNA binding activity in a major portion of receptors that are misfolded after removal of Hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3190–3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KA, Stancato LF, Owens-Grillo JK, Johnson JL, Krishna P, Toft DO, Pratt WB. The 23-kDa acidic protein in reticulocyte lysate is the weakly bound component of the HSP foldosome that is required for assembly of the glucocorticoid receptor into a functional heterocomplex with Hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18841–18847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Lou DY, Yamamoto KR. Three amino acid substitutions selectively disrupt the activation but not the repression function of the glucocorticoid receptor N terminus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4149–4156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen HM, Strahle U, Gloss B, Stewart F, Schmid W, Boshart M, Miksicek R, Schutz G. Cooperativity of glucocorticoid response elements located far upstream of the tyrosine aminotransferase gene. Cell. 1987;49:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Craig EA. Protein folding in vivo: Unraveling complex pathways. Cell. 1997;90:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80327-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Binding of p23 and Hsp90 during assembly with the progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:670–678. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.6.8592513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Toft DO. A novel chaperone complex for steroid receptors involving heat shock proteins, immunophilins, and p23. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24989–24993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the heart. Amer J Med. 1996;101:459–460. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch R, Garabedian MJ. Role for Hsp90-associated cochaperone p23 in estrogen receptor signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3748–3759. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralli A, Bohen SP, Yamamoto KR. LEM1, an ATP-binding-cassette transporter, selectively modulates the biological potency of steroid hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:4701–4705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefstin JA, Yamamoto KR. Allosteric effects of DNA on transcriptional regulators. Nature. 1998;392:885–888. doi: 10.1038/31860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, DeFranco DB. Chromatin recycling of glucocorticoid receptors: Implications for multiple roles of heat shock protein 90. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:355–365. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.3.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: The second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S, Iitaka M, Suzuki S, Fukaswa N. Decrease in serum levels of thyroid hormone in patients with coronary heart disease. Endocr J. 1996;6:657–663. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.43.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A, Foley R. Kinetics of glucocorticoid-receptor complexes in rat thymus cells. J Steroid Biochem. 1976;7:1117–1122. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(76)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A, Wira C, Young DA, Mosher KM, Hallahan C, Bell PA. Glucocorticoid receptor complexes and the earliest steps in the action of glucocorticoids on thymus cells. J Steroid Biochem. 1972;3:567–578. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(72)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat GEO, Downes M, Dowhan DH. Regulation of vertebrate muscle differentiation by thyroid hormone—The role of the MyoD gene family. BioEssays. 1995;17:211–218. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan DF, Lindquist S. Mutational analysis of Hsp90 function- interactions with a steroid receptor and a protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3917–3925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onate SA, Tsai SY, O'Maley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce D, Yamamoto KR. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor activities distinguished by nonreceptor factors at a composite response element. Science. 1993;259:1161–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.8382376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard D, Khursheed B, Garabedian MJ, Fortin MG, Lindquist S, Yamamoto KR. Reduced levels of Hsp90 compromise steroid receptor action in vivo. Nature. 1990;348:166–168. doi: 10.1038/348166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik A, Schutz G, Stewart AF. Glucocorticoids are required for establishment and maintenance of an alteration in chromatin structure: Induction leads to a reversible disruption of nucleosomes over an enhancer. EMBO J. 1991;10:2569–2576. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez ER, Tan CD, Onwuta US, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Parrillo JE. 3,5,3′-Triiodo-L-thyronine induces cardiac myocyte differentiation but not neuronal differentiation in P19 teratocarcinoma cells in a dose dependent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:652–658. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau GG, Baxter JD, Higgins SJ, Tomkins GM. Steroid-induced nuclear binding of glucocorticoid receptors in intact hepatoma cells. J Mol Biol. 1973;79:539–554. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif M, Privalsky ML. V-ErbA oncogene function in neoplasia correlates with its ability to repress retinoic acid receptor action. Cell. 1991;66:885–893. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JH, Mulvihill ER, Thomas PS, Palmiter RD. Commitment of chick oviduct tubular gland cells to produce ovalbumin mRNA during hormonal withdrawal and restimulation. J Cell Biol. 1980;87:142–151. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ, Kavlock RJ, Bartolome JV. Thyroid hormone differentially regulates cellular development in neonatal rat heart and kidney. Teratology. 1992;45:303–312. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420450309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Toft DO. Composition, assembly and activation of the avian progesterone receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90345-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Sullivan WP, Marion TN, Zaitsu K, Madden B, McCormick DJ, Toft DO. Identification of a 60-kilodalton stress-related protein, p60, which interacts with Hsp90 and Hsp70. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:869–876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco MD, Johnson R, Galante PE, Hanahan D, Yamamoto KR. A transition in transcriptional activation by the glucocorticoid and retinoic acid receptors at the tumor stage of dermal fibrosarcoma development. EMBO J. 1995;14:2217–2228. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth R, Briand PA, Picard D. Functional analysis of the yeast 40 kDa cyclophilin cyp40 and its role for viability and steroid receptor regulation. Biol Chem. 1997;378:381–391. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.5.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom L, Johansson C, Salto C, Barlow C, Barros AC, Baas F, Forrest D, Thorén P, Vennström B. Abnormal heart rate and body temperature in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:455–461. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaret KS, Yamamoto KR. Reversible and persistent changes in chromatin structure accompany activation of a glucocorticoid-dependent enhancer element. Cell. 1984;38:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]