Abstract

This article discusses Oppenheimer’s theory on marriage timing, reviews the way this theory was received in European demography and family sociology, and develops a new test of the theory using annual panel data from 13 European countries for the period 1994–2001. Several indicators of men’s economic status are used, including school enrollment, employment, type of labor contract, work experience, income, and education. Effects of these indicators are estimated for the transition to marriage and cohabitation, as well as for the transition from cohabitation to marriage. Country differences in these effects are examined as well. The evidence provides strong support for the male breadwinner hypothesis on the one hand, and for Oppenheimer’s career uncertainty hypothesis on the other. However, the relevance of these hypotheses also depends on the national context, and especially on the way gender roles are divided in a society.

Keywords: Marriage, Cohabitation, Education, Employment, Income, Europe

Résumé

Dans cet article relatif à la théorie d’Oppenheimer sur le calendrier du mariage, nous examinons la manière dont cette théorie a été perçue par la démographie européenne et la sociologie de la famille et nous testons à nouveau cette théorie à l’aide de données de panel annuel collectées dans 13 pays européens au cours de la période 1994–2001. Différents indicateurs du statut économique de l’homme sont utilisés, tels que la scolarisation, l’emploi, le type de contrat de travail, l’expérience professionnelle, le revenu et le niveau d’instruction. Les effets de ces indicateurs sont estimés pour l’entrée dans le mariage ou la cohabitation, ainsi que pour le passage de la cohabitation au mariage. Les différences entre pays des effets de ces indicateurs sont également examinées. Les résultats appuient fortement l’hypothèse de l’homme en tant que soutien économique de la famille d’une part, et d’autre part l’hypothèse d’instabilité professionnelle d’Oppenheimer. Cependant, la pertinence de ces hypothèses dépend également du contexte national, et plus spécialement de la répartition des rôles selon le genre dans la société étudiée.

Mots-clés: Mariage, Cohabitation, Instruction, Emploi, Revenu, Europe

Bringing Men Back in

The American demographer and sociologist Valerie Oppenheimer wrote a series of influential articles in which she emphasized the role of men’s socioeconomic position in demographic change, in particular in the declining rates of marriage and the underlying tendency to increasingly postpone and perhaps even forego marriage (Oppenheimer 1988, 2000, 2003; Oppenheimer et al. 1997). In this contribution, I review Oppenheimer’s original theoretical study, I discuss how her study was held up in empirical research in Europe, and I provide a new test of the theory for the European setting. In doing so, I try to resolve some remaining gaps in the empirical literature, and I evaluate whether the theory is equally valid in different countries that make up the European context. Given the recent economic crisis in the United States and in Europe, and the growing concerns about economic inequality, the influence of men’s economic position on marriage and family formation remains a vital concern.

At the time Oppenheimer began writing her articles on how men’s economic position influenced marriage formation—in the late 1980s and early 1990s—this was generally not a popular idea. The declining rates of marriage and increasing rates of divorce were typically conceptualized in terms of an "erosion of marriage." This erosion was explained in two different ways. One theory looked for the culprit in the growing economic role of women in society. This theory was voiced by demographers and economists working from a micro-economic perspective (Becker 1981; Espenshade 1985; Farley 1988), although, as Oppenheimer noted (1988, p. 575), it bore a strong resemblance to classic sociological theories formulated by functionalists like Talcot Parsons (Parsons 1949). The explanation basically argued that more symmetrical economic roles of men and women would lead to a decline in the gains to marriage, or to put it in Parsonian terms, would undermine marital solidarity.

The second explanation argued that the decline of marriage was related to value change, and in particular to the increasing need for individual autonomy on the one hand, and the ideological condemnation of traditional institutions like marriage on the other. This second perspective was expressed more strongly by European demographers like Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa although it was also used by the influential American demographers at the time (Bumpass 1990; Rindfuss and Van den Heuvel 1990). In their Second Demographic Transition theory, Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa argued that ideological change in combination with secularization was driving not only the postponement of marriage, but also the increase in cohabitation, the rise in divorce, and the decline of fertility (Lesthaeghe 1983; Lesthaeghe and Meekers 1986; Lesthaeghe and Surkuyn 1988; Van de Kaa 1987). While the first explanation saw the engine of the demographic transition in economic change, the second emphasized the primacy of cultural change. Both theories, however, were pessimistic about the future of marriage: the economic perspective saw marriage as incompatible with symmetrical gender roles, the second saw it as incompatible with individualistic values.

While there was a considerable debate between the proponents of economic and cultural explanations, Oppenheimer criticized both perspectives. First, she questioned the empirical evidence for the theories. For example, she noted that there were no signs of a so-called independence effect. Women with attractive economic resources were not less likely to enter marriage, as would be predicted from the micro-economic perspective (Oppenheimer and Lew 1995). Although women’s employment and education had an effect on fertility and divorce, this did not appear to be the case for marriage timing (Oppenheimer 1997). Oppenheimer also had empirical critique on the cultural perspective. When looking at simple descriptive statistics on what people want for themselves—on people’s hopes and desires—she noted that the majority of both single men and women still wanted to be married (Oppenheimer 1994). The anti-marriage ideology may have existed in feminist circles or in the pop culture of the sixties, but it had not spread to a larger audience in the way that, for example, egalitarian gender norms had done.

Oppenheimer also had theoretical criticisms of the two explanations (Oppenheimer 1994, 1997). First, she believed that the theories were basically about nonmarriage and not about delays in marriage. As other demographers also had observed, the declining marriage rate was primarily driven by increases in the age at marriage, and not so much by a decline in the proportion of persons who marry eventually, although the latter could of course not yet be observed in the late 1980s. Oppenheimer believed that people were postponing marriage, not foregoing it. This seems by and large correct now, although the proportion of the marrying persons among the lower educated in the United States did appear to decline (Goldstein and Kenney 2001). A second part of her theoretical critique was against the micro-economic model of specialization. Quoting historical demographic work, Oppenheimer noted that wives in the past had always worked for pay when circumstances required this. Wives worked to make ends meet when the husband was not making enough money, when he was unemployed, or when household costs were temporarily pressing (Oppenheimer 1982). Oppenheimer argued that specialization in marriage is an inflexible and risky strategy in many different societal contexts. If marriage was not based on a model of full specialization in the more distant past, Oppenheimer argued, why would it then cease to exist in the modern era in which wives began to work?

Oppenheimer not only criticized the then dominant perspectives on demographic change, she also presented an alternative. Her explanation can be placed in the economic rather than the cultural camp, but it was different in that it focused on men rather than women. During the 1980s and 1990s, young men’s economic position in the United States had deteriorated quickly, especially for those with little schooling. In the poor and uncertain economic prospects of young men, Oppenheimer saw an important potential for understanding the decline of marriage. Because the earlier explanation had focused more on women—especially through arguments about women’s economic independence—one could say that Oppenheimer was in fact "bringing men back into the debate." She did this in two different ways.

First, she reinstated older Malthusian ideas about the economic costs of marriage (Hajnal 1965; Easterlin 1980). As setting up and running a household costs money, men who are unable to fulfill the role of breadwinner will not be attractive marriage partners and fathers. Oppenheimer recognized that this traditional male-breadwinner hypothesis may have lost some of its force when gender roles become more symmetrical. Nonetheless, she argued that it would also be naive to expect men’s economic resources to become unimportant in influencing marriage prospects: this would be "throwing out the baby with the bathwater."

The second way in which she brought men back in the debate was through her uncertainty hypothesis (Oppenheimer 1988). The argument is that unstable careers, as indicated by low-status jobs, nonemployment, and irregular and temporary employment, signal uncertainty. This uncertainty applies not only to whether the husband will be able to provide in the future, but also to the type of life he will lead. Work structures the lifestyle a person will develop, and when men have not yet settled in their career it is difficult to predict what married life will be like. In this way, employment uncertainty impedes assortative mating and may therefore delay marriage.

An important difference between the breadwinner and the uncertainty hypotheses is that the former focuses primarily on the financial aspects of employment whereas the latter is also concerned with its social consequences. An implication is that the neo-Malthusian argument would be fully covered by effects of income, whereas the uncertainty argument would also be reflected in indicators like irregular attachment to the labor market, the amount of work experience, career trajectories, and temporary employment. In a separate article, Oppenheimer also developed and operationalized the concept of a stopgap job, i.e., a job that is not a reflection of an employee’s educational credentials and that is meant as temporary by both employer and employee (Oppenheimer and Kalmijn 1995). Men in such stopgap jobs would postpone marriage because they are not settled in their career and therefore cannot yet make a suitable match in the marriage market.

Compared to the other two perspectives, Oppenheimer’s theory has a more optimistic implication for the future of marriage. The prevailing explanations were rather pessimistic about the future of marriage—after all, female labor force participation was unlikely to decline in the future and individualism did not appear to be receding. In Oppenheimer’s theory, the economic position of young men largely depends on macro-economic conditions. Because unemployment rates tend to have cyclical rather than linear trend patterns, the economic position of young men could improve and this would then have positive repercussions for marriage. Moreover, the theory only implies the postponement of marriage until men accumulate more work experience and become settled in their career, and not an erosion of the institution of marriage, as the other theories seem to imply.

Oppenheimer's explanation had a second attractive feature: it could also explain another important demographic trend, namely the rise in cohabitation (Oppenheimer 2003). Oppenheimer argued that a man’s failure to provide economically would be less of a problem for cohabitation than for marriage. For many couples, cohabitation is a trial stage before marriage, and it may be that uncertainty about a young man’s position is more tolerable during the cohabiting stage than it would be for a long-term commitment to marriage. Assuming that the costs of breaking up a cohabiting union are lower, cohabitation can therefore provide a way for couples to reduce uncertainty about future career prospects. In a sense, Oppenheimer argued that a cultural innovation like cohabitation before marriage (on a massive scale) was the outcome of economic needs rather than the result of ideological change. In line with this, other authors even argued that cohabitation is a rational response to uncertainty: a flexible partnership well-suited for a flexible labor market (Mills et al. 2005).

In the United States, many studies have tested Oppenheimer’s theory. American research generally supports the view that poor economic prospects for men are associated with a delay in marriage. This has been demonstrated for a range of indicators, including employment per se, unstable employment, low earnings, and other indicators of career "immaturity" (Clarkberg 1999; Lichter et al. 1992; Lloyd and South 1996; Mare and Winship 1991; Oppenheimer 2003; Oppenheimer et al. 1997; Sassler and Schoen 1999; Smock and Manning 1997; Sweeney 2002; Xie et al. 2003). There is also evidence in the United States that cohabitation is less strongly influenced by men’s economic position than marriage, although there is no clear reverse income effect, i.e., that the poor are being selected into cohabiting unions. Furthermore, in the United States, the income effect on marriage timing appears to be stable over time. Sweeney (2002) compared two cohorts in the United States and found that in the cohort marrying during the 1980s and 1990s, men’s income had an equally strong positive effect on the entry into marriage as in the cohort marrying during the 1960s and 1970s (Sweeney 2002).

Testing the Theory in Europe

In this article, I develop a new test of Oppenheimer’s theory for the European context. There are several reasons to expect Oppenheimer’s theory to also apply to Europe. First, the demographic trends that occurred in Europe were similar, although sometimes less dramatic and sometimes occurring later. The age at marriage has risen, the rate of marriage has declined, and cohabitation has increased as well (Kiernan 2002; Lesthaeghe 1983; Van de Kaa 1987). Second, many European countries experienced economic problems that were similar to those in the United States. They were especially salient for outsiders on the labor market, such as young adults, ethnic minorities, and women. Several authors argued that partly in response to economic globalization, young European men (and women) faced increasing levels of economic uncertainty in their transition from school to work (Blossfeld et al. 2005). In many European countries, especially in Southern Europe, levels of youth unemployment were even higher than in the United States, a phenomenon which has often been linked to the higher degrees of employment protection in Europe (Müller and Gangl 2003; Nickell 1997).

There are also reasons to believe that the theory would be less applicable to Europe. One counter argument lies in the role of the welfare state. In several European societies, and particularly in social-democratic welfare states like Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands, social security is more generous and more universally provided than it is in the United States (Arts and Gelissen 2002; Esping-Andersen 1993). This means that in many European countries, young men receive unemployment benefits when they are out of work. Moreover, for those who have never worked, basic welfare is provided, albeit at a minimum level. As a result, young jobless men can still bear the cost of setting up a household. Following the neo-Malthusian argument, it could thus be argued that employment problems do not per se lead to marriage postponement in Europe. A rebuttal of this point is that Oppenheimer’s argument about uncertainty and assortative mating, which is not only about money, but also about stability and predictability, could still apply to Europe. A young man who is on unemployment benefits remains an uncertain candidate on the marriage market even if he has the financial means to support a household at that point in time.

Another important difference between the American and the European case lies in the degree of heterogeneity. Although the United States is certainly not a homogeneous country—there are important ethnic, racial, and regional differences—it is fair to say that Europe is more heterogeneous (at least regionally) than the United States. In comparative studies, it has often been argued that European countries can be rated on a continuum from more traditional societies such as Spain, Greece, and Italy on the one hand, to more modern and more economically developed societies such as Sweden and the Netherlands on the other (Hagenaars et al. 2003). These differences are expressed in a number of social and cultural domains, including differences in marriage and family living. For example, in more traditional European societies, cohabitation and divorce are less common and less accepted, marriage has a higher social status, gender roles in marriage are more unequal, female labor force participation is lower, and extended family ties are stronger (Hans-Peter Blossfeld and Hakim 1997; Gelissen 2003; Kalmijn 2003; Knudsen and Waerness 2008; Reher 1998). These indicators are strongly correlated, both with each other and with the level of economic development in a country (GDP). This degree of heterogeneity suggests that Oppenheimer’s theory may not apply equally to all European countries. For example, in contexts where gender roles are more egalitarian, men’s economic situation could be less important for the entry into marriage and cohabitation. In these settings, men are not the only breadwinners and women’s economic resources should be of growing importance, making men’s economic resources less important.

What has the evidence in Europe shown so far? Perhaps the most important source of evidence comes from a large multi-nation project initiated by the German sociologist Blossfeld and his colleagues (Blossfeld et al. 2005). In this project, Blossfeld brought together a number of demographers and sociologists from different parts of the world (with an overrepresentation of European countries), with the aim of examining the effect of men and women’s individual economic resources on the timing of marriage and parenthood. While the authors used their own country-specific longitudinal data, they used similar methods and variables, leading to a reasonably uniform and comparable set of outcomes. The project’s goal was to test the exact same set of hypotheses in each country. The hypotheses were borrowed in part from Oppenheimer’s work but they were translated by Mills and Blossfeld to make them fit for a broader societal setting (Mills and Blossfeld 2005). The articles were combined in a volume for which Oppenheimer wrote the foreword (Blossfeld et al. 2005).

The articles in Blossfeld’s volume provide generally positive evidence for the theory in the European countries studied (Germany, the Netherlands, France, Sweden, Hungary, Great Britain, Italy, and Spain). In virtually all countries, school enrollment—one of the indicators of uncertainty—negatively affected the entry into marriage. More importantly, men’s unemployment appeared to lower the chances of entering marriage in most countries (Bernardi and Nazio 2005; Kieffer et al. 2005; Kurz et al. 2005; Liefbroer 2005; Noguera et al. 2005; Robert and Bukodi 2005). In Britain, an effect of unemployment was observed only on the transition from cohabitation to marriage, and not on the transition from being single to living together (Francesconi and Golsch 2005). In Sweden, only unemployment after leaving school appeared to delay marriage formation, not unemployment after a period of employment (Bygren et al. 2005). Some evidence was also found for the effect of temporary contracts. In Italy, Spain, France, and the Netherlands, it was shown that men who were employed temporarily were less likely to enter marriage than men who had permanent employment. In Germany and Hungary, there was no effect of temporary work, however, and in several other countries, the effect could not be studied. A recent analyses of fertility in Europe has also pointed to the delaying effect of temporary contracts (Adsera 2011).

Outside the Blossfeld project, there were a number of important individual articles in which aspects of Oppenheimer’s theory were tested. For example, in Sweden, it was found that men’s employment increased the chances of union formation while it did not affect the chances of marriage after cohabitation (Bracher and Santow 1998). In Norway, men’s employment increased the chances of marrying after being single and the chance of marrying after living together (Kravdal 1999). In the Netherlands, men’s employment had a stronger effect on direct marriage than on cohabitation but there was no effect of employment on marriage after cohabitation (Kalmijn and Luijkx 2005; cf. Liefbroer 2005). The evidence outside Europe (i.e., Israel) has been supportive as well (Raz-Yurovich 2010), as has been the evidence in Central and Eastern Europe, a region not included in the present article (Gerber and Berman 2010).

While the role of employment has often been studied in Europe, less is known about how men’s income and earnings affect union formation. Many of the studies discussed above were based on retrospective rather than prospective longitudinal data. There are few good sources of large-scale panel data in Europe. The panel data that exist have been collected by economists and labor market researchers and do not always have the desirable demographic indicators. Because income cannot be measured well in a retrospective fashion, this has also meant that we know little about the income effects on marriage and divorce in Europe. This is unfortunate because employment and income need to be examined simultaneously, especially if one wants to make a distinction between the neo-Malthusian breadwinner hypothesis on the one hand, and Oppenheimer’s uncertainty hypothesis on the other. Because in many European welfare states nonemployment does not, per se, mean no income, these two factors are not perfectly correlated.

Another drawback of the prevailing evidence is that most studies are based on single countries. Blossfeld’s multi-nation project is clearly a major step forward in trying to summarize the evidence for Europe as a whole, but the analyses are not pooled so the results can only be summarized verbally. Moreover, possible differences that exist between countries can be described but they cannot be compared or tested in a more rigorous fashion. For these reasons, there is still work to be done.

In the remainder of this article, I address the following research questions. First, to what extent does men’s economic position affect union formation? In answering this question, I not only look at employment, but also I look at men’s income, work experience, and type of labor contract. By looking at income and employment patterns simultaneously, I obtain more direct evidence on the underlying mechanisms. The period for which I answer this question is 1994–2004. In virtually all European countries, unemployment rates increased substantially in the early 1990s before declining again in the mid to late 1990s (OECD 2009). In Italy, Greece, and Belgium, unemployment remained high in the late 1990s but began to decline later, in the early 2000s. In other words, for most countries, the period that I examine covers a recovery stage of the economy, a stage which should have been positive for marriage and family formation.

Second, are the effects of men’s economic position similar or different for the chances of entering marriage and the chances of entering a cohabiting union? With this part of the study, I replicate the last influential study of Oppenheimer (2003), in which she studied this issue for the United States. We would expect effects to be weaker for cohabitation than for marriage: marriage would require a stronger economic underpinning than cohabitation (Kravdal 1999; Oppenheimer 2003). In addition, I examine the chances that cohabiting unions turn into marriage. Here too, Oppenheimer expects men’s economic position to have an effect, but because those who cohabit already have an independent household, the effects of income will probably be weaker.

Third, to what extent are the effects of men’s economic position on union formation different across societal contexts? In this part, I focus on differences between traditional and egalitarian societies. The expectation is that men’s economic characteristics remain important in traditional societies but are less important in more modern, egalitarian ones. By looking at differences among societal contexts, I try to generalize the cross-cohort comparison that Sweeney (2002) made for the United States. Answering this question is also of more general importance because if we find conditions under which the theory is (not) true, this could in principle lead to theoretical progress in the field.

Data, Methods, and Variables

I use panel data that are collected in the same format for a number of European countries, i.e., the European Community Household Panel (ECHP). The ECHP was an annual panel survey held between 1994 and 2001 (Behr et al. 2005; Clémenceau and Verma 1996). Samples are large and representative, and (almost) the same questionnaire was used each year. For the analyses in this article, I use data from 13 countries: Denmark, Finland, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece. My sample is limited to men who were never married in the first wave of the panel. Hence, I look at the first union formation. Although I am able to exclude previously married men, I cannot exclude men who ended a cohabiting union before the panel began. Never married men who were cohabiting in the first wave are also included because these men can make the transition from cohabitation to marriage. The first wave of data from the Netherlands is excluded because no information is available on cohabitation status. The total number of men is 17,743.

There have been previous demographic analyses of the ECHP most notably by Adsera (2011) who analyzes the effect of individual and aggregate labor market characteristics on fertility. Although Adsera focused more on women than on men, her general conclusion is that labor market uncertainty is very influential in delaying fertility, in line with the perspective suggested above. In the current article, we go back one step by analyzing how labor market uncertainty affects union formation, a transition which probably remains the most important necessary condition for family formation. We also focus explicitly on men.

Dependent Variables and Models

I use discrete time event-history analysis by estimating logistic regression models on a person-year file. The person-year file begins at the first wave and ends in the last wave or when a transition is made. As is the case with all event-history analyses of panel data, some men were already married in the first wave. Such left truncation problems can be solved in principle, but not without losing our time-varying independent variables (Guo 1993). The first logit model is estimated for person-years in which men are single and never married. The dependent variable is whether a man is living without a partner in wave t and living with a partner in wave t + 1 (union formation). In the second logit model, I estimated which choice was made, cohabitation or marriage, using only the person-years in which the event occurred. This sequential approach is slightly different from the approach taken by Oppenheimer, who estimated multinomial logit (i.e., competing risk) models (2003). The sequential approach does not need the assumption implicit in a competing risk model that the two choices—cohabitation and marriage—are independent of each other. This assumption is problematic because it is plausible that unmeasured factors like personality, wealth, attractiveness, and the like, influence marriage and cohabitation to the same extent (Hill et al. 1993). If a person is single in year t, missing in year t + 1, and married or cohabiting in year t + 2, I also regarded this as an event. Duration dependency is modeled with two age effects, according to the approach developed by Blossfeld and Huinink (1991). Blossfeld used log (age—a1) and log (a2—age) to capture the nonlinear age-dependency of union formation, where a1 is the lowest and a2 the highest age in the sample. There were 4,492 transitions to a first union of which 2,499 were to cohabitation and 1,993 to marriage.

The second logit model is estimated for person-years in which men were living with a partner without being married. The dependent variable is defined as living with a partner unmarried in wave t and being married in wave t + 1 (marriage after cohabitation). Respondents who were living alone in wave t + 1 are truncated. Hence, separation is treated as a competing risk. If a person is cohabiting in year t, not in the panel in year t + 1, and married in year t + 2, I also regarded this as an event. Duration dependency could not be modeled directly because for those who are in a cohabitating union in the first wave of the panel, no data on the start of the union is available. As an alternative, I use age as a proxy. Age is obviously less ideal than duration since persons enter a cohabiting union at different ages. There were 1,498 transitions from cohabitation to marriage. It is noted that there was no question in the interview about whether the partner in one wave was the same partner as in the previous wave. Hence, I could not check if a man changed (cohabiting) partners between the subsequent waves, nor could I check if the married partner was the same person as the cohabiting partner in the previous wave.

Independent Variables

All independent variables, except where noted, refer to time t. As the dependent variables refer to whether or not a transition was made between the time t and t + 1, the independent variables precede the dependent variable in time. Employment is measured with two dummy variables. The first indicates a man is working on a paid job or is self-employed at the time of the interview for at least 15 h a week. The second variable indicates other less common forms of employment, such as military service, apprenticeships, unpaid family work, and working less than 15 h. Given that a man is employed, I also considered the type of contract he has. Temporary contracts include fixed-term or short-term contracts, casual work with no contract, and "some other working arrangement" that is not a permanent contract (all included within the 15+ hours category). The coding is cumulative so that the effect of temporary work refers to the difference between the men with a temporary contract and men with a permanent contract. I also include whether a person is enrolled in full-time schooling in the interview week.

Next to a man’s current situation, I consider his work history. Data on work history are obtained from a monthly calendar that all respondents had to fill out. For the year t − 1, I counted the number of months that a man was employed, self-employed, or in school (hereafter called "active"). This variable is not available in the Netherlands. Means were imputed and a dummy-variable for the Netherlands is included. I checked whether the effects of this variable were different when excluding the Netherlands but this was not the case.

Income is the other main variable of interest. I consider personal income and not only income from work since social security income may also provide a stable source of income. Ideally, we would like to measure the income a man had in the interview month or in the 12 months before the interview. Unfortunately, incomes are measured for (full) calendar years only. To solve this, I took a weighted average of the income in calendar year t − 1 and the income in calendar year t, using information on the month of interview. For example, if the interview was in September 1994, income for that person-year is 9/12 of the income earned in 1994 plus 3/12 of the income earned in 1993. It is noted that some of the income in year t may be earned after a man marries. The weights are also addressing this problem. Marrying in the year of the interview is more likely when the interview took place early in the year, but then, this income receives a lower weight. I corrected all incomes for changes in the Consumer Price Index and converted them to pounds sterling. To estimate effects of income in a comparable way across countries, I used a relative income measure. I first calculated income quintiles in each country using data from all men in the first wave of the ECHP. Next, I used these quintiles to categorize the men in the person-year file. I also use a linear income variable which is coded 1–5 for the five quintiles.

Three control variables are used which may affect union formation: general health (time varying), the highest level of educational attainment, and the year of the interview (using dummies). Health is controlled because having a poor health may be detrimental for finding a partner and is also related to job and income opportunities (Waldron et al. 1996). Descriptive findings for the independent variables for each country are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means of independent variables in person-year file by country

| Year (1–8) | Age | General health (1–5) | Secondary education | Tertiary education | Working 15+ hours | Other work | Temporary contract | Enrolled in school | Months active (0–12) | Relative income (1–5) | Income in pounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK (n = 7,585) | 4.07 | 31.88 | 3.91 | 0.08 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 9.94 | 3.04 | 10546 |

| Ireland (n = 7,741) | 3.40 | 32.31 | 4.37 | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.62 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 9.52 | 2.70 | 7184 |

| Germany (n = 9,581) | 4.06 | 30.12 | 3.79 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.41 | 2.55 | 9536 |

| Austria (n = 5,782) | 4.48 | 29.12 | 4.40 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 10.67 | 2.50 | 8995 |

| France (n = 11,385) | 3.90 | 31.99 | 3.87 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 9.49 | 2.52 | 8537 |

| Belgium (n = 3,842) | 3.81 | 32.25 | 4.17 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 9.96 | 2.46 | 9182 |

| Netherlands (n = 5,248) | 4.52 | 32.66 | 4.11 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 9.00 | 2.44 | 9841 |

| Italy (n = 18,316) | 4.02 | 29.88 | 4.11 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 8.55 | 2.49 | 4696 |

| Greece (n = 7,942) | 3.89 | 29.64 | 4.69 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 9.57 | 2.57 | 4220 |

| Spain (n = 12,764) | 3.83 | 30.83 | 4.08 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 8.68 | 2.54 | 4553 |

| Portugal (n = 10,097) | 4.09 | 29.42 | 3.69 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 10.06 | 2.88 | 3062 |

| Finland (n = 5,360) | 5.01 | 32.95 | 4.06 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 9.45 | 2.55 | 11526 |

| Denmark (n = 5,381) | 3.88 | 33.38 | 4.42 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 10.20 | 2.99 | 12814 |

| Total (n = 111,024) | 4.03 | 30.97 | 4.09 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 9.50 | 2.62 | 7227 |

Source: ECHP (own calculations)

To explore differences across societies, I constructed two measures at the macro level. First, I considered a measure of the division of household labor in marriage in a society. This measure was obtained from a article by Knudsen and Waerness (2008) and measures the extent to which husbands and wives share four household tasks (i.e., laundry, grocery shopping, meal preparation, caring for sick family members). The second measure is the female labor force participation rate in the 1990s, which is defined as the percentage of women aged 20–49 who are active in the labor force (obtained from ILO, Geneva). The two macro-level indicators are strongly correlated. Countries in which wives participate more often in the labor force are also countries in which the household tasks are divided more equally (r = .74). The most traditional societies are Southern European countries, the most egalitarian are Northern European countries. Western European countries are located in between these two. I construct a single macro-level indicator, which is the means of the two standardized items. The scale is also standardized.

Results

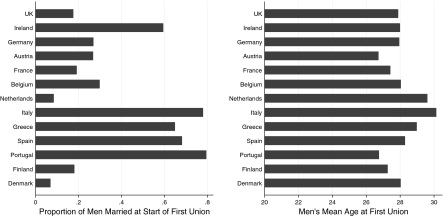

We start with some descriptive results. Figure 1 shows that there are small differences within Europe in the age at first union entry. In most countries, the mean age at entry is between 27 and 29. Male age at entry is low in Portugal and Austria, and high in the Netherlands and Italy. The differences do not coincide with a modern-traditional continuum. For example, the age at union formation is quite high in Italy and Greece where the family is a strong institution. This already points to the potential importance of unemployment. In Southern Europe, youth unemployment is high. When we look at the type of first union chosen by men, presented in the left side of Fig. 1, we see clearer differences. In Western Europe, and even more in Northern Europe, direct marriage is a minority experience. In many countries, more than 80% of men cohabit first. In Southern Europe, the proportions are almost reversed: 60–80% of the men in these countries marry directly. The United Kingdom resembles Western Europe but Ireland resembles the south, with most men choosing marriage as their first way to enter a union. This most likely reflects the role of the Catholic church in Ireland.

Fig. 1.

Men’s first union formation in 13 countries

The effects of men’s economic characteristics on union entry are presented in Table 2. We discuss Model A first, which includes employment variables but no income variables. We note the important role of employment. The odds of entering a union are 58% higher for employed men than for men who are not employed and not in school (e 457). Interestingly, there is also an effect on the type of union. Employed men have a 48% higher odds of marrying rather than cohabiting. Hence, nonemployment is less incompatible with cohabitation than with marriage. The type of labor contract also matters for the choice between marriage and cohabitation. Compared to men with a permanent job, men with a temporary job who enter a union are 23% less likely to choose marriage than cohabitation. We also note that school enrollment has a negative effect on union entry while it does not affect the type of union.

Table 2.

Discrete time event history models of union formation: logit regression coefficients and p-values in parentheses

| Union formation | Marriage vs. cohabitation | Marriage after cohabitation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | Model G | Model H | Model I | |

| Ln (age—15) | 0.841*** (0.000) | 0.661*** (0.000) | 0.676*** (0.000) | 0.746*** (0.000) | 0.745*** (0.000) | 0.741*** (0.000) | −0.230* (0.040) | −0.317** (0.006) | −0.316** (0.006) |

| Ln (65—age) | 1.872*** (0.000) | 1.816*** (0.000) | 1.847*** (0.000) | 0.810*** (0.000) | 0.813*** (0.000) | 0.809*** (0.000) | 0.296* (0.038) | 0.264 (0.061) | 0.268 (0.058) |

| General health | 0.106*** (0.000) | 0.100*** (0.000) | 0.098*** (0.000) | 0.135* (0.012) | 0.135* (0.013) | 0.135* (0.012) | 0.107** (0.008) | 0.104* (0.010) | 0.103* (0.011) |

| Education secondary versus primary | 0.029 (0.491) | −0.002 (0.955) | −0.007 (0.867) | −0.046 (0.655) | −0.035 (0.731) | −0.047 (0.648) | 0.005 (0.951) | −0.012 (0.890) | −0.014 (0.873) |

| Education tertiary versus primary | 0.225*** (0.000) | 0.141** (0.003) | 0.122** (0.010) | 0.113 (0.311) | 0.149 (0.194) | 0.111 (0.326) | 0.408*** (0.000) | 0.361*** (0.000) | 0.349*** (0.000) |

| Working 15+ hours versus no work/school | 0.457*** (0.000) | 0.193** (0.003) | 0.220*** (0.001) | 0.450** (0.003) | 0.419** (0.007) | 0.445** (0.004) | 0.178 (0.166) | 0.090 (0.495) | 0.102 (0.434) |

| Other employed versus no work/school | 0.144 (0.088) | 0.204* (0.016) | 0.188* (0.026) | 0.279 (0.176) | 0.350 (0.096) | 0.282 (0.173) | 0.237 (0.277) | 0.250 (0.254) | 0.245 (0.263) |

| Temporary versus fixed contract | −0.067 (0.182) | 0.026 (0.609) | 0.031 (0.544) | −0.253* (0.033) | −0.262* (0.028) | −0.251* (0.035) | −0.120 (0.249) | −0.086 (0.410) | −0.090 (0.386) |

| In school versus no versus no work/school | −0.623*** (0.000) | −0.431***(0.000) | −0.468*** (0.000) | −0.180 (0.388) | −0.089 (0.679) | −0.173 (0.412) | −0.515* (0.015) | −0.410 (0.059) | −0.424* (0.046) |

| Months worked last 2 years | 0.022*** (0.000) | 0.006 (0.243) | 0.007 (0.178) | −0.008 (0.518) | −0.011 (0.405) | −0.009 (0.504) | 0.031* (0.010) | 0.021 (0.089) | 0.023 (0.066) |

| First income quintile versus third quintile | −0.604*** (0.000) | −0.272 (0.054) | −0.256* (0.044) | ||||||

| Second income quintile versus third quintile | −0.253*** (0.000) | −0.039 (0.735) | −0.182* (0.037) | ||||||

| Fourth income quintile versus third quintile | 0.232*** (0.000) | −0.136 (0.210) | 0.094 (0.224) | ||||||

| Fifth income quintile versus third quintile | 0.366*** (0.000) | −0.127 (0.328) | 0.109 (0.233) | ||||||

| Linear income (1–5) | 0.239*** (0.000) | 0.007 (0.861) | 0.098*** (0.001) | ||||||

| Constant | −11.814*** (0.000) | −10.677*** (0.000) | −11.595*** (0.000) | −7.903*** (0.000) | −7.789*** (0.000) | −7.895*** (0.000) | −3.346*** (0.000) | −2.771*** (0.000) | −3.138*** (0.000) |

| N | 77621 | 77621 | 77621 | 4472 | 4472 | 4472 | 11678 | 11678 | 11678 |

| χ2 | 2240 | 2460 | 2451 | 1625 | 1630 | 1625 | 335 | 348 | 346 |

Note: Controlled for country and year dummies

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Next to the effects of current employment characteristics, we see effects of men’s work history. The more months men were employed or otherwise active in the past calendar year, the more likely they are to enter a union in the next two calendar years. The magnitude of the effect is considerable. Men who were active for an entire year were e 12 × .022 = 30% more likely to enter a union in the next 2 years than men who were inactive the entire year. This effect comes on top of the effect of a man’s current employment situation. There is no effect of work history on the choice between marriage and cohabitation.

In sum, the findings from Model A and Model D confirm that men who are not yet settled in their career postpone union formation. The findings also confirm that cohabitation is less sensitive to economic insecurity than marriage, although this applies more to employment per se and the type of employment than to a man’s work history.

In Model B and Model E, we add income variables to the model. We see that income has a strong effect on union entry. The reference group is the middle quintile. Each higher income group has a higher chance of entering a union. The poorest quintile of men are 45% less likely to enter a union than the middle quintile, while the richest quintile are 44% more likely to do so. The income effects increase monotonically but the differences between the quintiles become smaller at higher income levels. A formal test shows that the effect is not strictly linear: The nonlinear model for union formation (Model B) has a better fit than the linear model (Model C, χ2 = 9.3, p = .03). When we look at the income effect on choice between the marriage and cohabitation, we only see one marginally significant effect. Men in the lowest quintile who enter a union are 31% more likely than the middle quintile to choose cohabitation rather than marriage (p = .054). This result seems to confirm the notion of cohabitation as the poor man’s marriage, although the poor are still more likely not to enter a union in the first place.

When we compare the two models for union entry (Model A and B), the employment effects that we observed in Model A are reduced by more than half once income is added to the model. In other words, the effects of employment and work history run in part via income. Nevertheless, the employment effect remains statistically significant even when income is included, which means that the influence of employment on union formation also has a non-financial element. The latter finding is in line with Oppenheimer’s uncertainty argument. It is also interesting to observe that the effects of employment and temporary jobs on the choice between the marriage and cohabitation are not affected by whether or not income is added (compare Model D and E). This is logical, given the weaker income effect on this outcome. Hence, the non-financial aspects of work are more important for the type of union than for the chance of entering a union in the first place. In this sense, Oppenheimer’s uncertainty theory seems to work better for the type of union than for union formation per se.

Several of the control variables also have an effect. Men in good health are more likely to enter a union. Moreover, men in good health more often choose marriage than cohabitation. This confirms theories about selection into marriage and suggests that screening or selection may be less strong for cohabitation. Education, finally, has a positive effect on union entry but these effects are reduced when income is controlled for.

In the last columns of Table 2, we focus on marriage formation after cohabitation (Model G, H, and I). We see that it is not affected by employment, but being enrolled in school does reduce the chance of marrying. We also find that men who worked more months in the past are more likely to marry. Income also has a significant effect. The higher the men’s income during cohabitation, the more likely they are to change from cohabitation to marriage. When comparing the linear income effect on marriage after cohabitation with the linear effect on initial union formation, it appears that income is less important for marriage after cohabitation (b = .10) than it is for union formation after being single (b = .21). This is in line with the neo-Malthusian hypothesis, which suggests that it is primarily for initial union entry that the costs of setting up a household play a role (although the wedding is a cost factor which applies specifically to marriage).

The control variables also have effects on the transition to marriage. Men in good health are more likely to experience a transition from cohabitation to marriage, suggesting that the selection effects also play a role in the decision to marry, not only in the decision to live together. We also see that higher educated cohabiting men are more likely to marry, hence, for the higher educated, cohabitation is less often seen as a long-term option. This effect is not explained by income.

Do the effects we found vary across societal contexts? To assess this, I present interaction effects of key independent variables with the macro-level indicator of traditional versus egalitarian societies. Interaction effects are presented in Table 3. The p-values are based on standard errors that are corrected for the clustering of cases within countries. This yields a more conservative test for macro-level effects and is a good alternative to multilevel models when the number of units at the macro level is limited. To check for outliers at the country level, I calculated DFBETAs for the interaction effects of modernization and employment, and of modernization and income, and re-estimated the models while leaving out countries for which DFBETAs exceeded the critical value (Kalmijn 2010; Ruiter and De Graaf 2006). DFBETA is calculated as the difference in an effect with and without the outlier divided by the standard error of the effect. These outlier analyses are presented in the third and fourth columns of Table 3.

Table 3.

Discrete time event history models of union formation with interactions: logit regression coefficients and p-values in parentheses

| Model A all cases | Model B all cases | Model A w/o outliers | Model B w/o outliers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln (age—15) | 0.953*** (0.000) | 0.781** (0.002) | 0.943*** (0.001) | 0.686* (0.036) |

| Ln (65—age) | 1.970*** (0.000) | 1.956*** (0.000) | 1.934*** (0.001) | 2.040* (0.010) |

| General health | 0.121** (0.001) | 0.107** (0.002) | 0.102** (0.006) | 0.119* (0.016) |

| Education secondary versus primary | 0.071 (0.287) | 0.023 (0.732) | 0.031 (0.638) | 0.115 (0.079) |

| Education tertiary versus primary | 0.271*** (0.000) | 0.152* (0.014) | 0.248*** (0.000) | 0.224*** (0.001) |

| Working 15+ hours versus no work/school | 0.501*** (0.000) | 0.194*** (0.000) | 0.549*** (0.000) | 0.175*** (0.000) |

| In school versus no versus no work/school | −0.672*** (0.000) | −0.604*** (0.000) | −0.614*** (0.000) | −0.673*** (0.000) |

| Income linear | 0.242*** (0.000) | 0.243*** (0.000) | ||

| Index (traditional—egalitarian) | 1.916 (0.177) | 2.075 (0.144) | 2.092 (0.262) | 2.039 (0.327) |

| Index * ln (age—15) | −0.278 (0.058) | −0.314* (0.037) | −0.311 (0.110) | −0.217 (0.272) |

| Index * ln (65—age) | −0.233 (0.442) | −0.262 (0.386) | −0.288 (0.471) | −0.309 (0.485) |

| Index * health | −0.003 (0.914) | −0.004 (0.872) | −0.007 (0.718) | −0.005 (0.897) |

| Index * secondary education | 0.079 (0.333) | 0.087 (0.285) | 0.086 (0.368) | 0.121* (0.041) |

| Index * tertiary education | 0.119 (0.106) | 0.130 (0.079) | 0.139 (0.127) | 0.205*** (0.000) |

| Index * working | −0.158** (0.001) | −0.122** (0.001) | −0.152*** (0.000) | −0.098* (0.043) |

| Index * enrolled | 0.236** (0.001) | 0.210** (0.002) | 0.215** (0.004) | 0.288*** (0.000) |

| Index * income | 0.002 (0.935) | −0.037** (0.008) | ||

| Constant | −13.107*** (0.000) | −12.953*** (0.000) |

−12.853*** (0.000) |

−13.112*** (0.000) |

| N | 77621 | 77621 | 68837 | 58354 |

Note: Controlled for country and year dummies. p-values corrected for clustering. Outliers for Model A are Denmark and Greece, for Model B these are Italy and the United Kingdom

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

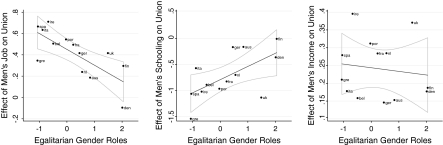

In Table 3, we see a negative interaction of the societal index with men’s employment (b = −.16, p < .01). Hence, the average effect of employment (b = .50) is reduced by 32% for each standard deviation increase in the egalitarian context (.16/.50). This shows that the effect of men’s employment on the entry into a union is considerably weaker in more egalitarian countries than in more traditional countries. I also present the effects for each country separately in a graph (Fig. 2). In this graph, the effect of selected independent variables is plotted against the macro-level index. Although the graph does not provide a test, like the interaction effect, it does give a good intuitive feel of the importance of the interaction effect. In line with expectations, the graph shows that in more traditional societies like Spain, Italy, and Ireland, the effect of men’s employment is quite strong. In more egalitarian countries like the Netherlands, Denmark, and Finland, the effect is weaker although generally not zero. We see similar interaction effects of school enrollment and the societal index. Men’s enrollment in school deters union formation but this effect is weaker in more egalitarian societies. Both interaction effects are in line with the hypothesis.

Fig. 2.

Effects of men’s economic characteristics on union entry

Table 3 further shows no negative interaction of the societal index with men’s income effect on union formation. After deleting two outliers (Italy and the United Kingdom), the interaction becomes negative and significant (b = −.037, p = .01). Hence, for these 11 countries, the effect of men’s income on union formation is weaker in more egalitarian countries than in more traditional countries. The magnitude of the effect is a 15% reduction in the income effect per standard deviation increase in the egalitarian context (.037/.234). When we look at the graph, the pattern appears to be weaker than it was for employment. Spain and Portugal reveal strong effects of men’s income and Denmark and the Netherlands have weak effects. However, there are also outliers like the United Kingdom (stronger effect than expected) and Italy and Belgium (weaker effect than expected).

So far, these results apply to union formation regardless of the type of union. Traditional and egalitarian societies also differ in the extent to which cohabitation occurs. The more egalitarian countries like Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands also have the highest levels of cohabitation (Soons and Kalmijn 2009). Because the effects of men’s economic position differ depending on whether marriage or cohabitation is the outcome, the results could in part be due to such compositional differences. For this reason, I also look at the entry into marriage only (either after being single or after cohabitation). The interaction with employment is −.066 (p = .11), the interaction with enrollment is .326 (p < .01), and the interaction with income is −.073 (p < .01). Hence, the employment interaction effect is weaker in this model, although still negative, while the other interaction effects are not affected. We therefore conclude that part of the reason why the employment effects depend on the context lies in the fact that unions are more often unmarried unions in more egalitarian societies. Even apart from that, however, there is evidence that men’s economic status matters more for marriage in more traditional societies.

Conclusion and Discussion

This article has re-examined the importance of Oppenheimer’s theory on marriage timing in the European context. By and large, the European evidence supports the theory. Unemployment, little work experience, low income, and temporary employment on the part of men deter union formation. By analyzing income and employment effects simultaneously in a panel perspective, it was possible to obtain more direct evidence for the two contrasting hypotheses suggested by Oppenheimer, i.e., the neo-Malthusian male breadwinner hypothesis and the career uncertainty hypothesis (sometimes also called the career instability or immaturity hypothesis). Many previous European analyses have not been able to take income into account and have therefore not been able to separate these two mechanisms empirically.

My analyses first show that income effects are strong and significant, which supports the male breadwinner hypothesis. Second, the income effects explain about half of the effects of employment and work experience, suggesting that employment effects by themselves are not sufficient evidence for the uncertainty hypothesis. However, the employment effects do not completely disappear once income is added. This suggests that employment effects on union formation are more than just a matter of financial resources, in line with the uncertainty hypothesis.

By analyzing the choice between cohabitation and marriage, further evidence could be obtained for the two hypotheses. Marriage in Europe appears to be more sensitive to men’s economic position than cohabitation. Men who are not employed or who have temporary jobs are more likely to choose cohabitation rather than marriage. This finding provides additional evidence for the uncertainty hypothesis since cohabitation is more like a trial marriage and hence, more compatible with uncertainty in other life domains (i.e., employment). We do not, however, see a clear income effect on the choice between marriage and cohabitation. Hence, the choice between marriage and cohabitation has more to do with employment uncertainty than with income. There is a small effect of the lowest income group, however. Among men who enter a union, the 20% poorest men are more likely to choose cohabitation. Hence, there is some evidence that cohabitation is the "poor man’s marriage."

Following Oppenheimer’s last study, I also examined the transition from cohabitation to marriage. We would expect economic uncertainty to also reduce the chances of a transition from cohabitation to marriage, but in general, the effects we find are weaker for this transition. The weaker income effect could be due to the fact that the cost of setting up a household plays no role for this transition. Income also had little effect on the initial choice between marriage and cohabitation. While this is in line with the neo-Malthusian argument, the finding that the employment effects on the transition from cohabitation to marriage are also weaker is unexpected. Other authors have found this too (e.g., Bracher and Santow 1998; Liefbroer 2005). Future research is needed to find out why this is the case. One speculation is that fertility and housing play a role. If couples buy a house or have a child, they may decide to marry. Although such transitions may be partly governed by economic uncertainty, they may also be exogenous and hence reduce the effects of other determinants like employment. Another speculation has to do with the lack of information on the (female) partner. The partner may have become economically more secure during the cohabitation stage, thereby promoting the transition to marriage, but we do not observe such changes.

European countries differ considerably in terms of their economic, social, and cultural characteristics, and so, it is important to also examine country variation in the degree to which the theory applies. We hypothesized that men’s economic position would be less influential in more developed countries where gender roles are more symmetrical. We find some evidence in support of this notion. The effects of men’s employment and school enrollment on union formation are stronger in more traditional societies than in more egalitarian ones. Income effects are also weaker in egalitarian societies but the evidence for this pattern is weaker. Our interpretation is that in egalitarian settings, the costs of setting up a household are more often shared between men and women. Hence, men can afford to experiment with their career if they have a partner who has a (more) stable career. Similarly, women may attach less weight to the career options of men than they did in more traditional circumstances and for instance, pay more attention to other traits, such as men’s willingness to participate in child rearing.

My finding is in contrast to a previous cohort comparison for the United States which suggested that men’s economic effects on marriage timing did not change over time (Sweeney 2002). Perhaps this difference is due to the limited time period that was examined in Sweeney’s trend study, a design which may have reduced the variance in contextual gender roles. At the same time, however, it needs to be investigated whether the patterns that I found still hold when a larger number of countries is considered. The income interaction effects, for example, are sensitive to outliers and therefore less convincing. More units at the macro-level will be needed to confirm this finding.

In closing, it is important to re-emphasize on the role of women. Although Oppenheimer was justifiably "bringing men back" into the debate at a time when there was too little attention on the changing economic fate of young (American) men, the growing egalitarian model that is now supported by many couples in Europe and the United States, suggests that men and women should be examined simultaneously for a better understanding of trends and differentials in marriage and cohabitation. Traditionally, studies of women were largely done from a Beckerian perspective in which it was argued that women’s status would lead to a decline of marriage (and fertility). Currently, we can speculate that a strong economic position and career stability on the part of women might foster marriage. How this works from a couple perspective is not yet clear. It could be that certainity on just one side—either the man or the woman—is enough to make stronger union commitments. In this case, one career supports the other. Alternatively, it could be that both the man’s and the woman’s career need to have been settled before couples enter a more committed union.

In this respect, it is somewhat unfortunate that analyses of marriage (timing or formation) have often been one-sided, focusing either on men or on women. This design is unavoidable given that the partner of a respondent is typically observed too late, i.e., when the respondent is married or living with the partner. Empirically, this problem does not exist when we observe cohabiting couples’ chances of marrying. Some authors in the past have regarded the transition from cohabitation to marriage as a two-sided problem and have analyzed economic characteristics of both partners in one model (Lichter et al. 2006; Smock and Manning 1997). These studies have not been able to examine the more important entry into a first union, however. For this transition, the problem can, in principle, be solved by examining dating couples in a more systematic fashion. For example, prospective surveys could collect data on the school and work careers of both members of a dating couple and subsequently analyze whether or not (and when) they begin to live together, while using the dissolution of the dating relationship as a competing risk. In this way, the analysis of marriage and cohabitation can become truly two-sided and the economic characteristics of men and women can be included in one model. There are some innovative sociological studies of transitions from dating to cohabitation and marriage, but so far, they have not focused on the partners’ economic characteristics (Joyner and Kao 2005).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Adsera A. Where are the babies? Labor market conditions and fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population. 2011;27(1):1–32. doi: 10.1007/s10680-010-9222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts W, Gelissen J. Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European Social Policy. 2002;12(2):137–158. doi: 10.1177/0952872002012002114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Behr A, Bellgardt E, Rendtel U. Extent and determinants of panel attrition in the European Community Household Panel. European Sociological Review. 2005;21(5):489–512. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi F, Nazio T. Globalization and the transition to adulthood in Italy. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 349–376. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Hakim C. A comparative perspective on part-time work. In: Blossfeld H-P, Hakim C, editors. Between equalization and marginalization: Women working part-time in Europe and the United States of America. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Huinink J. Human capital investments or norms of role transition: How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(1):143–168. doi: 10.1086/229743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty, and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bracher M, Santow G. Economic independence and union formation in Sweden. Population Studies. 1998;52(3):275–294. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000150466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LJ. What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography. 1990;27(4):483–498. doi: 10.2307/2061566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygren M, Duvander A-Z, Hultin M. Elements of uncertainty in life courses. Transitions to adulthood in Sweden. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkberg M. The price of partnering: The role of economic well-being in young adults’ first union experiences. Social Forces. 1999;77(3):945–968. doi: 10.2307/3005967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clémenceau A, Verma V. Methodology of the European community household panel. Statistics in Transition. 1996;2(7):1023–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R. A. (1980). Birth and fortune. New York: Basic Books.

- Espenshade TJ. Marriage trends in America: Estimates, implications, and underlying causes. Population and Development Review. 1985;11(2):193–245. doi: 10.2307/1973487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Social foundations of postindustrial economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Farley R. After the starting line: Blacks and women in an uphill race. Demography. 1988;25(4):477–495. doi: 10.2307/2061316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi M, Golsch K. The process of globalization and transitions to adulthood in Britain. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 249–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gelissen JPTM. Cross-national differences in public consent to divorce: Effects of cultural, structural and compositional factors. In: Arts W, Halman LCJM, Hagenaars JAP, editors. The cultural diversity of European unity: Findings, explanations and reflections from the European values study. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers; 2003. pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber TP, Berman D. Entry into marriage and cohabitation in Russia, 1985–2000: Trends, correlates, and implications for the Second Demographic Transition. European Journal of Population. 2010;26(1):3–32. doi: 10.1007/s10680-009-9196-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Kenney CT. Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New Cohort Forecasts of First Marriage for U.S. Women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(4):506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G. Event-history analyses for left-truncated data. Sociological Methodology. 1993;23:217–243. doi: 10.2307/271011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars J, Halman L, Moors G. Exploring Europe’s basic values map. In: Arts W, Hagenaars J, Halman L, editors. The cultural diversity of European unity. Leiden: Brill; 2003. pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal, J. (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In D. V. Flass & D. E. C. Eversley (Eds.), Population in history (pp. 101–143). London: Edward Arnold.

- Hill DH, Axinn WG, Thornton A. Competing hazards with shared unmeasured risk factors. Sociological Methodology. 1993;23:245–277. doi: 10.2307/271012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Kao G. Interracial relationships and the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2005;70(4):563–581. doi: 10.1177/000312240507000402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Country differences in sex-role attitudes: Cultural and economic explanations. In: Arts W, Hagenaars J, Halman L, editors. The cultural diversity of European unity: Findings, explanations and reflections from the European Values Study. Leiden: Brill; 2003. pp. 311–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Country differences in the effects of divorce on well-being: The role of norms, support, and selectivity. European Sociological Review. 2010;26(4):475–490. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, Luijkx R. Has the reciprocal relationship between employment and marriage changed for men? An analysis of the life histories of men born in The Netherlands between 1930 and 1970. Population Studies. 2005;59(2):211–231. doi: 10.1080/00324720500099587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer A, Marry C, Meron M, Solaz A. The case of France. Family formation in an uncertain labor market. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K. Cohabitation in Western Europe: Trends, issues, and implications. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Just living together: Implications of cohabitation on families, children, and social policy. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University; 2002. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen K, Waerness K. National context and spouses’ housework in 34 countries. European Sociological Review. 2008;24(1):97–113. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcm037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal O. Does marriage require a stronger economic underpinning than informal cohabitation? Population Studies. 1999;53(1):63–80. doi: 10.1080/00324720308067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz K, Steinhage N, Golsch K. Case study Germany. Global competition, uncertainty and the transition to adulthood. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R. A century of demographic and cultural change in Western Europe: An exploration of underlying dimensions. Population and Development Review. 1983;9(3):411–435. doi: 10.2307/1973316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Meekers D. Value changes and the dimensions of familialism in the European community. European Journal of Population. 1986;2:225–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01796593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Surkuyn J. Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review. 1988;14(1):1–45. doi: 10.2307/1972499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, McLaughlin DK, Kephart G, Landry DJ. Race and the retreat from marriage: A shortage of marriageable men? American Sociological Review. 1992;57(6):781–799. doi: 10.2307/2096123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z, Mellot LM. Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography. 2006;43(2):223–240. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC. Transition from youth to adulthood in the Netherlands. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KM, South SJ. Contextual influences on young men’s transition to first marriage. Social Forces. 1996;74(3):1097–1120. doi: 10.2307/2580394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mare RD, Winship C. Socioeconomic change and the decline of marriage for blacks and whites. In: Jencks C, Peterson P, editors. The urban underclass. Washington: The Brookings Institution; 1991. pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mills M, Blossfeld H-P. Globalization, uncertainty and the early life course. A theoretical perspective. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mills M, Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E. Becoming and adult in uncertain times: A 14-country comparison of the losers of globalization. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 423–441. [Google Scholar]

- Müller W, Gangl M, editors. Transitions from education to work in Europe—The integration of youth into EU labour markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nickell S. Unemployment and labor market rigidities: Europe versus North America. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1997;11(3):55–74. doi: 10.1257/jep.11.3.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noguera CS, Castro Martin T, Bonmati AS. The Spanish case. The effect of the globalization process on the transition to adulthood. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 375–402. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2009). OECD factbook 2009: Economic, environmental and social statistics.

- Oppenheimer VK. Work and the family. New York: Academic; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing: Assortative mating under varying degrees of uncertainty. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(3):563–591. doi: 10.1086/229030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review. 1994;20(2):293–342. doi: 10.2307/2137521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women’s employment and the gain to marriage: The specialization and trading model of marriage. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:431–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. The continuing importance of men’s economic position in marriage formation. In: Waite L, Bachrach C, Hindin M, Thomson E, Thornton A, editors. Ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career-development process. Demography. 2003;40(1):127–149. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK, Kalmijn M. Life-cycle jobs. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 1995;14:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK, Kalmijn M, Lim N. Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography. 1997;34(3):311–330. doi: 10.2307/3038286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer, V. K., & Lew, V. (1995). American marriage formation in the eighties: How important was women’s economic independence? In K. Oppenheim Mason & A.-M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries (pp. 105–138). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Parsons T. The social structure of the family. In: Anshen R, editor. The family: Its function and destiny. New York: Harper; 1949. pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Raz-Yurovich L. Men’s and women’s economic activity and first marriage: Jews in Israel, 1987–1995. Demographic Research. 2010;22:933–964. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reher DS. Family ties in Western Europe: Persistent contrasts. Population and Development Review. 1998;24(2):203–234. doi: 10.2307/2807972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Van den Heuvel A. Cohabitation: A precursor to marriage or an alternative to being single? Population and Development Review. 1990;16(4):703–726. doi: 10.2307/1972963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robert P, Bukodi E. The effects of the globalization process on the transition to adulthood in Hungary. In: Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K, editors. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge; 2005. pp. 177–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter S, De Graaf ND. National context, religiosity, and volunteering: Results from 53 countries. American Sociological Review. 2006;71(2):191–210. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Schoen R. The effect of attitudes and economic activity on marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(1):147–159. doi: 10.2307/353890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD. Cohabiting partners’ economic circumstances and marriage. Demography. 1997;34(3):331–341. doi: 10.2307/3038287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soons J, Kalmijn M. Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(5):1141–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00660.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM. Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review. 2002;67(1):132–147. doi: 10.2307/3088937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kaa DJ. Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin. 1987;42(1):1–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I, Hughes ME, Brooks TL. Marriage protection and marriage selection: Prospective evidence for reciprocal effects of marital status and health. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(1):113–123. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Raymo JM, Goyette K, Thornton A. Economic potential and entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography. 2003;40(2):351–367. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]