Abstract

Although it has been established that the processing factors involved in pre-mRNA splicing and 3′-end formation can influence each other positively, the molecular basis of this coupling interaction was not known. Stimulation of pre-mRNA splicing by an adjacent cis-linked cleavage and polyadenylation site in HeLa cell nuclear extract is shown to occur at an early step in splicing, the binding of U2AF 65 to the pyrimidine tract of the intron 3′ splice site. The carboxyl terminus of poly(A) polymerase (PAP) previously has been implicated indirectly in the coupling process. We demonstrate that a fusion protein containing the 20 carboxy-terminal amino acids of PAP, when tethered downstream of an intron, increases splicing efficiency and, like the entire 3′-end formation machinery, stimulates U2AF 65 binding to the intron. The carboxy-terminal domain of PAP makes a direct and specific interaction with residues 17–47 of U2AF 65, implicating this interaction in the coupling of splicing and 3′-end formation.

Keywords: RNA processing, cleavage, polyadenylation, splicing, poly(A) polymerase, U2AF 65

Before being transported out of the nucleus as mRNAs, primary gene transcripts undergo a series of co- and post-transcriptional maturation events. In all cases this includes capping of the 5′ end of the transcript and formation of the mature 3′-end, most commonly through cleavage and polyadenylation. Most transcripts in multicellular eukaryotes also contain intervening sequences that are removed by splicing. Although these processes are usually studied in isolation, ample evidence exists to demonstrate that the various events that constitute pre-mRNA maturation occur in an integrated fashion.

The first indication of this was the observation that adjacent introns in a pre-mRNA affect one another's splicing efficiency (Robberson et al. 1990; Hoffman and Grabowski 1992; Berget 1995). These results gave rise to the exon definition model of intron recognition, which posits that the 3′ splice site of an upstream intron helps to increase the efficiency of recognition of the 5′ splice site of a downstream intron by components of the splicing machinery and vice versa. The earliest events in intron recognition involve binding of U1 snRNP to the 5′ splice site (Rosbash and Séraphin 1991) and BBP/SF1 and U2AF 65/MUD2 to the branchpoint and pyrimidine tract regions of the 3′ splice site (Ruskin et al. 1988; Zamore et al. 1992; Staknis and Reed 1994a,b; Abovich and Rosbash 1997; Berglund et al. 1997, 1998; Rain et al. 1998). The interactions that link upstream 3′ splice sites and downstream 5′ splice sites involve interactions between U1 snRNP and U2AF 65 that are thought to be mediated by SR proteins (Fu and Maniatis 1992; Hoffman and Grabowski 1992; Chiara and Reed 1995; Manley and Tacke 1996, Valcárcel and Green 1996).

A further set of integrative interactions that has been uncovered recently involves RNA polymerase II (Pol II), the enzyme responsible for pre-mRNA transcription, and various components of the RNA processing machinery (for review, see Neugebauer and Roth 1997). The carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of Pol II is required in vivo for pre-mRNA capping, splicing, and 3′-end formation to proceed efficiently (McCracken et al. 1997a,b). The CTD is formed from multiple heptapeptide repeats that become highly phosphorylated in a reversible manner when Pol II progresses from transcription initiation to transcript elongation (Laybourn and Dahmus 1990; Arias et al. 1991). The phosphorylated CTD specifically interacts with components of the capping enzyme (Cho et al. 1997; McCracken et al. 1997b). Because capping does not occur when the CTD is truncated (McCracken et al. 1997b) this interaction is thought to be required to bring capping enzyme to its site of action.

In principle, because of the influence of the cap structure on other RNA processing events (see below), this interaction might also explain the effects of the CTD on splicing and 3′-end formation. However, because direct interactions between both splicing factors and factors involved in cleavage and polyadenylation and the CTD have been observed (Neugebauer and Roth 1997), it is also possible that multiple interactions between the CTD and different RNA processing factors occur as transcription proceeds.

The cap structure, through its binding to the nuclear cap-binding complex (CBC) (Izaurralde et al. 1994, 1995; Kataoka et al. 1994, 1995) has the potential to affect both splicing and polyadenylation. CBC stimulates U1 snRNP binding to the cap-proximal 5′ splice site (Inoue et al. 1989; Colot et al. 1996; Lewis et al. 1996a,b) and thus replaces the function of an upstream 3′ splice site in aiding recognition of the 5′-most splice site in the primary transcript. Although the interaction between CBC and U1 snRNP is not thought to be direct (Lewis et al. 1996a), a mediator of this interaction has not yet been identified. Similarly, the cap structure stimulates 3′-end formation on transcripts that lack introns (Gilmartin et al. 1988; Cooke and Alwine 1996; Flaherty et al. 1997). This stimulation also requires CBC and involves interaction between CBC and the 3′-end formation machinery (Flaherty et al. 1997).

In transcripts that contain introns, this CBC-dependent interaction is replaced by cross-exon interactions between the ultimate 3′ splice site and the site of 3′-end formation, which, at least in some cases, are mutually stimulatory (Niwa et al. 1990; Niwa and Berget 1991; Nesic et al. 1993, 1995; Wassarman and Steitz 1993; Nesic and Maquat 1994; Cooke and Alwine 1996; Gunderson et al. 1997; Bauren et al. 1998). The molecular basis of these stimulatory interactions is not defined. However, while investigating the mechanism by which both a dimer of U1A protein and U1 70K protein, the latter as part of U1 snRNP, inhibit pre-mRNA 3′-end formation (Boelens et al. 1993; van Gelder et al. 1993; Gunderson et al. 1994, 1997, 1998) it was found that peptides derived from U1A protein that interact with the carboxy-terminal 20 amino acids of poly(A) polymerase (PAP) uncouple splicing and polyadenylation (Gunderson et al. 1997). This suggested that the cross-exon interactions involved in the stimulation of splicing by the 3′-end formation machinery would involve this region of PAP. Here we provide direct proof that the carboxy-terminal region of PAP stimulates splicing and provide evidence that this involves an interaction between PAP and U2AF 65, whose consequence is increased binding of U2AF 65 to the pyrimidine tract of the 3′ splice site adjacent to the 3′-end formation signals.

Results

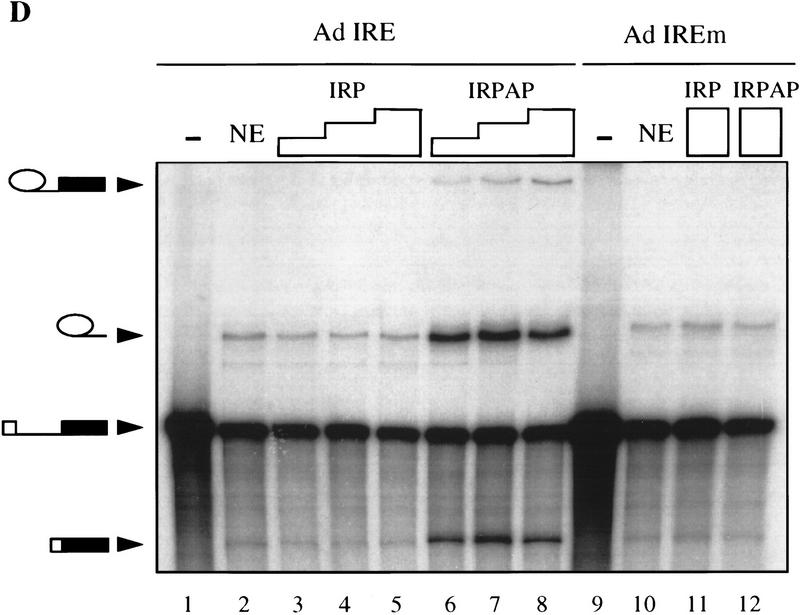

The cleavage/polyadenylation site stimulates an early recognition event at the 3′ splice site

Previously, we have reported in vitro conditions in HeLa nuclear extracts that support the stimulatory effect of a cleavage/polyadenylation site on splicing with a pre-mRNA construct consisting of the adenovirus I major late intron and the cleavage/polyadenylation signal from adenovirus L3 (Gunderson et al. 1997). To determine which step of splicing was stimulated, we examined splicing complex formation by native gel electrophoresis on two matched RNA substrates containing either the wild-type adenovirus L3 cleavage/polyadenylation site (AAUAAA) or an inactive mutant version (AAGAAA) located downstream of the major late intron. In a time course experiment, spliceosome formation on the RNA containing the AAUAAA sequence was readily detectable, whereas spliceosome assembly did not efficiently proceed to A complex formation (Konarska and Sharp 1986; Michaud and Reed 1993) on the intron linked to the AAGAAA mutant site (Fig. 1A). To determine whether the AAUAAA sequence could stimulate A complex formation on the 3′ splice site in the absence of a 5′ splice site (Konarska and Sharp 1986, Staknis and Reed 1994a) we examined substrates that contain only the 3′ half of the intron and the wild-type or mutant cleavage/polyadenylation site. Formation of A complex was detected with the RNA containing the 3′ splice site and the AAUAAA sequence (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–3). However, formation of A complex was barely detected with the RNA containing the AAGAAA sequence (Fig. 1B, lanes 4,5) and was not detected when the branchpoint sequence was mutated (Fig. 1B, lanes 6,7), demonstrating that the complexes seen were related to splicing rather than to 3′-end formation. We conclude that the cleavage and polyadenylation site stimulates A complex formation on the branchpoint of the pre-mRNA.

Figure 1.

A cleavage/polyadenylation site stimulates 3′ splice site recognition. Shown is time course of splicing complex assembly. RNAs 593 nucleotides long containing the adenovirus I major late intron and a wild-type or mutant adenovirus L3 cleavage/polyadenylation site (5′ → 3′-U and 5′ → 3′-G) (A) or RNAs 211 nucleotides long containing the 3′ splice site of the adenovirus I major late intron and the wild-type or mutant adenovirus L3 cleavage/polyadenylation site (3′-U and 3′-G) or a branchpoint mutation and a wild-type cleavage/polyadenylation site (BP-U) (B) were incubated with HeLa nuclear extract for the times indicated. Heparin was then added, and an aliquot of each reaction was loaded on a native gel. The bands corresponding to the H, E, A, B, C, E3′ and A3′ complexes are indicated.

The cleavage/polyadenylation site stimulates U2AF 65 binding to the pyrimidine tract of the upstream 3′ splice site

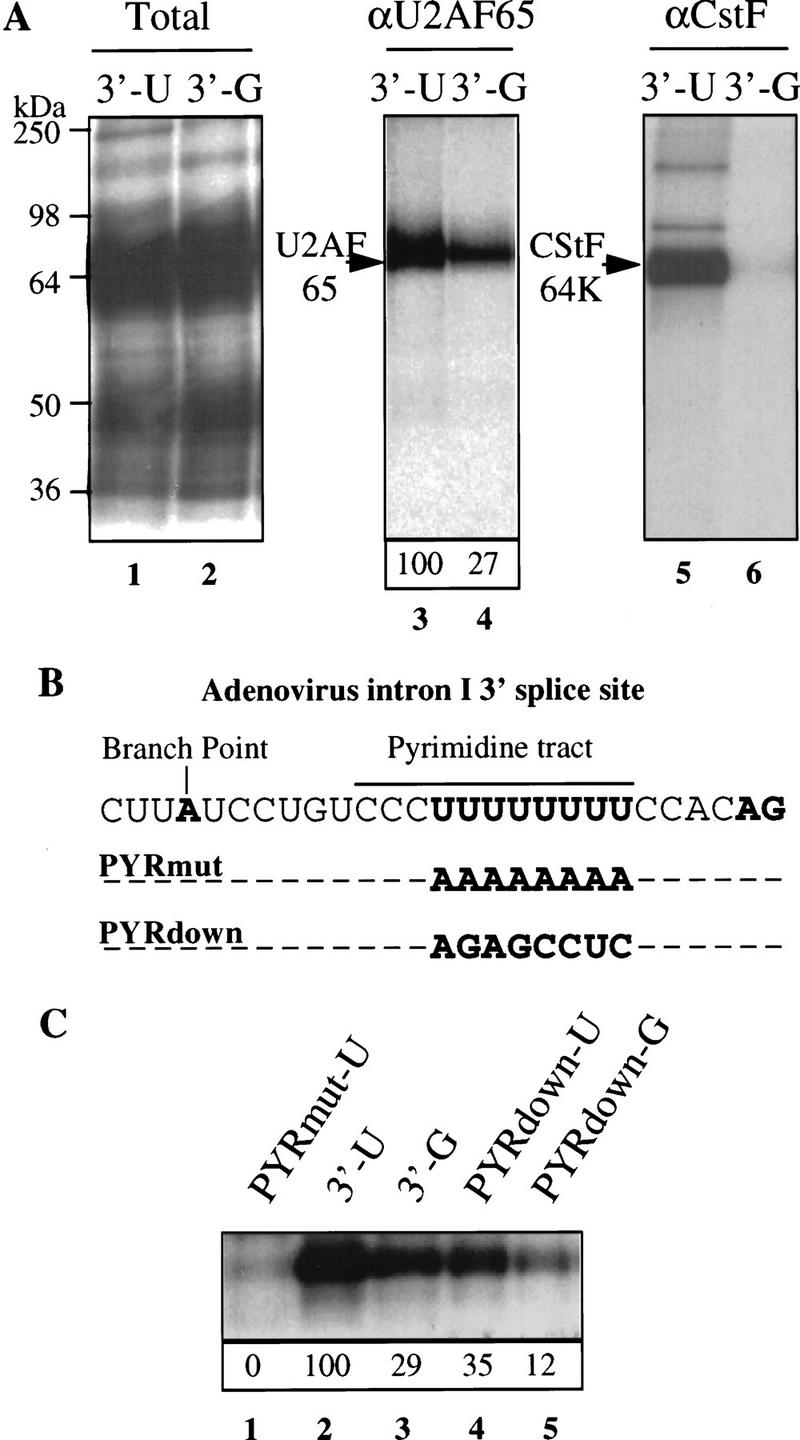

As U2AF 65 binding to the pyrimidine tract of the 3′ splice site promotes U2 snRNP binding to the branch site, we examined whether the AAUAAA sequence could stimulate U2AF 65 binding. UV cross-linking experiments were performed with the RNAs containing the 3′ splice site and the adenovirus L3 wild type or mutant cleavage/polyadenylation site (Fig. 2A). The complex cross-linking pattern could be resolved by immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies. Immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody directed against CStF 64 (MacDonald et al. 1994), a subunit of the multisubunit factor that binds the G/U-rich downstream sequence element, was used as a control to show that the cleavage/polyadenylation machinery bound to the RNAs containing the AAUAAA sequence but not to the RNA that contains the AAGAAA sequence (Fig. 2A, lanes 5,6). Immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody against U2AF 65 (Gama-Carvalho et al. 1997) showed that this protein was bound to the RNA containing the 3′ splice site (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Mutation of the AAUAAA sequence to AAGAAA resulted in a three- to fourfold reduction in U2AF 65 cross-linking (Fig. 2A, lane 4).

Figure 2.

A cleavage/polyadenylation site stimulates U2AF 65 binding to an upstream 3′ splice site. (A) RNAs 211 nucleotides long containing the 3′ splice site of the adenovirus I major late intron and the wild-type or mutant adenovirus L3 cleavage and polyadenylation site (3′-U and 3′-G) were incubated in HeLa nuclear extract and cross-linked by UV irradiation. Cross-linked polypeptides were either fractionated directly by SDS-PAGE (lanes 1,2, total) or immunoprecipitated before fractionation with the MC3 monoclonal antibody directed against U2AF 65 (Gama-Carvalho et al. 1997) (lanes 3,4, αU2AF 65) or the 64-kD subunit of CstF (MacDonald et al. 1994) (lanes 5,6, αCstF). The results of six independent U2AF 65 immunoprecipitation experiments were averaged, and the result is presented in lanes 3 and 4. The value for the 3′-U substrate was set to 100. (B) Details of the sequence of the wild-type adenovirus I major late 3′ splice site and the two mutants used. (PYRmut) The pyrimidine tract has been almost completely mutated to a purine tract; (PYRdown) the pyrimidine tract has been changed to that of the rat preprotachykinin exon 4, 3′ splice site. (C) RNAs 211 nucleotides long containing the 3′ splice site and the wild-type or mutant adenovirus L3 cleavage/polyadenylation site were cross-linked by UV irradiation. Cross-linked polypeptides were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal antibodies directed against U2AF 65 and separated by SDS-PAGE. Three separate experiments were quantified, and the average values are given below. The 3′-U substrate was set to a value of 100.

These results were confirmed by investigating the effect of the AAUAAA sequence on the binding of U2AF 65 to 3′ splice sites with various pyrimidine contents (Fig. 2B). There was no detectable U2AF 65 binding to an RNA in which the uridines of the pyrimidine tract were substituted by adenines, showing that the cross-linking reflects U2AF 65 binding to the pyrimidine tract of the 3′ splice site (Fig. 2B,C; PYR mut-U). The AAUAAA sequence stimulated U2AF 65 binding not only to the strong adenovirus pyrimidine tract (Fig. 2C, lanes 2,3) but also to the weaker pyrimidine tract of the 3′ splice site of the rat preprotachykinin exon 4 gene (Fig. 2B,C, lanes 4,5). This pyrimidine tract was chosen because it was shown previously that the recognition of this site by U2AF 65 is stimulated by the presence of a downstream 5′ splice site (Hoffman and Grabowski 1992).

Thus, the effect of the AAUAAA sequence on U2AF 65 binding to an upstream 3′ splice site partly mimics that of a downstream 5′ splice site. Unlike a downstream 5′ splice site, however, the cleavage/polyadenylation site also stimulated U2AF 65 binding to the strong pyrimidine tract of the adenovirus I major late intron.

The carboxyl terminus of PAP stimulates pre-mRNA splicing in vitro

Previously, we showed that addition of a peptide corresponding to the PAP-interacting region of the U1A protein conjugated to BSA causes uncoupling of cleavage and polyadenylation from intron splicing (Gunderson et al. 1997). This effect was proposed to be due to interaction of the U1A peptide–BSA conjugate with the 20 amino acids located at the carboxyl terminus of PAP and suggested that this region of PAP would be involved in the coupling of cleavage/polyadenylation and splicing (Gunderson et al. 1997).

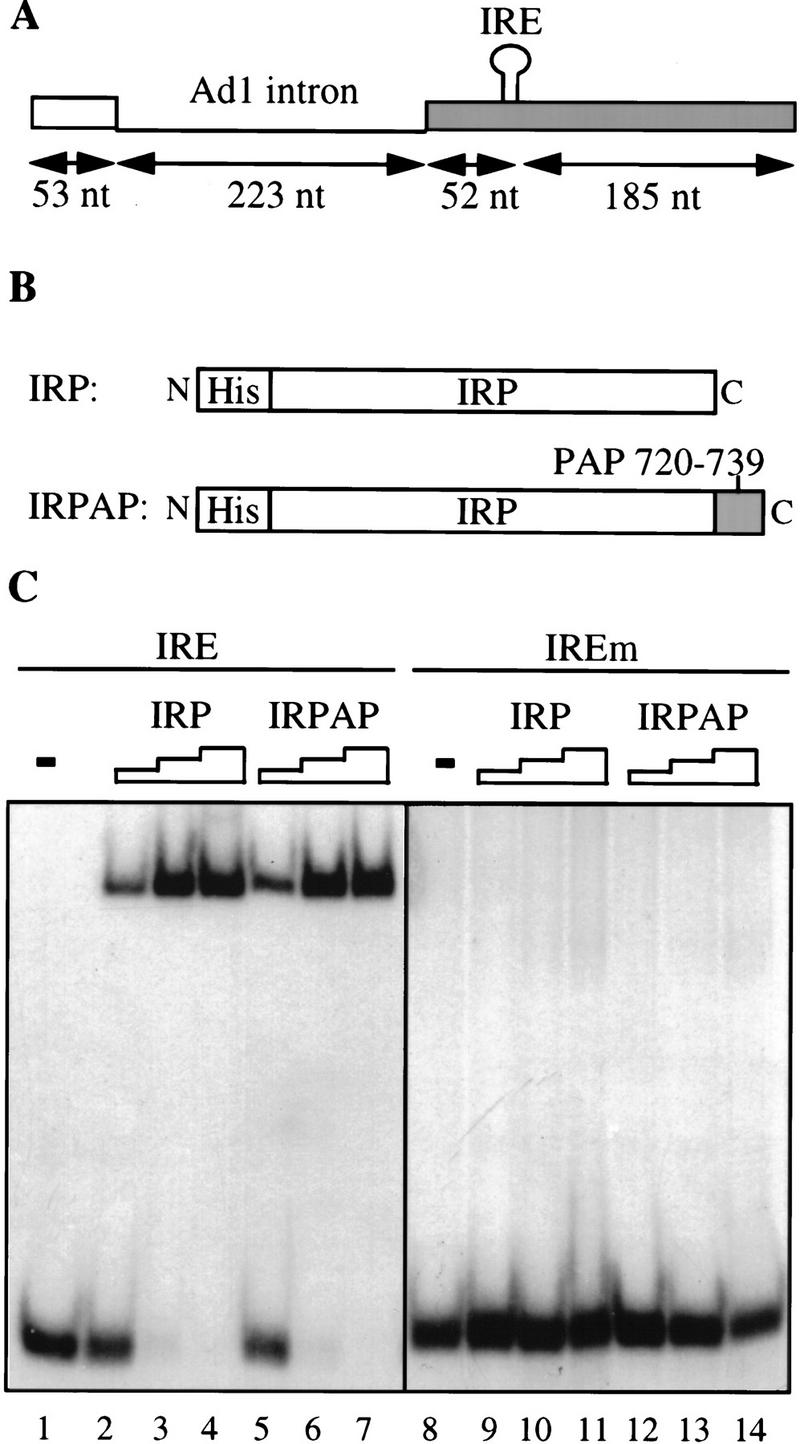

To examine this hypothesis more directly, we wished to tether the carboxy-terminal region of PAP to the RNA downstream of an intron and to examine the effect on the efficiency of splicing. The last 20 residues of PAP were therefore fused to an RNA-binding domain that could be used to position it on a pre-mRNA. IRP (iron regulatory protein), which binds the IRE (iron responsive element), was chosen to tether the carboxyl terminus of PAP to the RNA. The IRP–IRE interaction has been thoroughly characterized and shown to require an IRE of 18 nucleotides (for review, see Hentze and Kuhn 1996). Moreover, deletion of a single cytosine residue from the IRE impairs the binding of IRP (Hentze et al. 1987), and this mutant binding site can be used to construct a control splicing substrate.

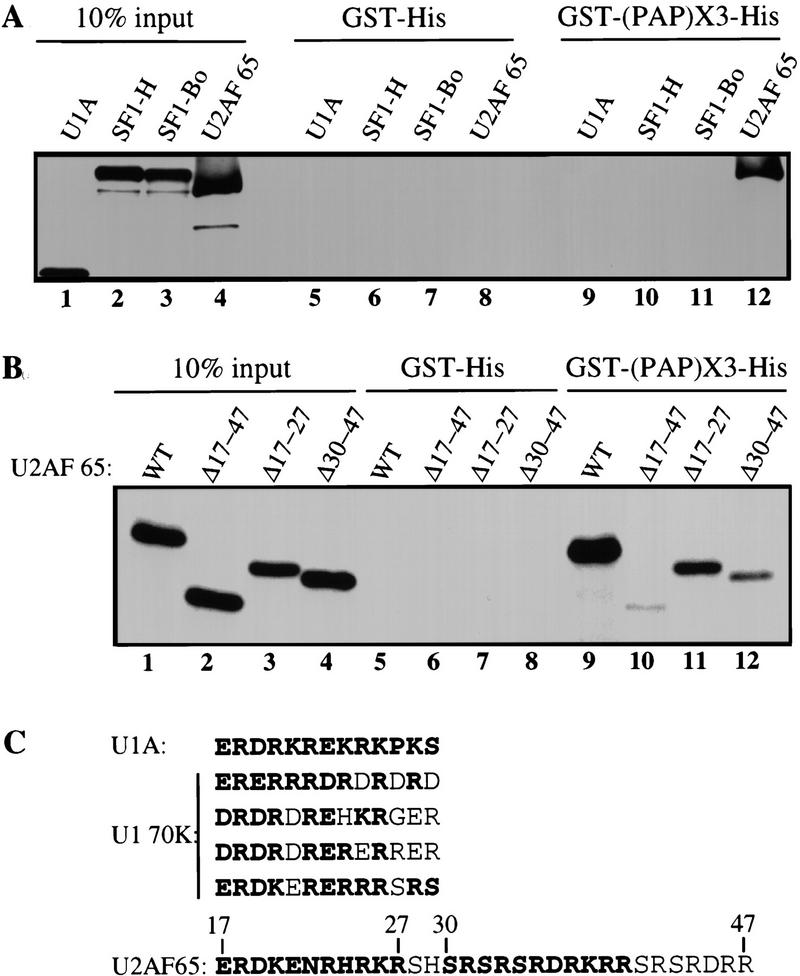

Pre-mRNA substrates were generated that contained either the wild-type IRE element (Ad IRE) or the mutant IRE (Ad IREm) positioned 52 nucleotides downstream of the adenovirus I major late intron (Fig. 3A). IRP and a fusion protein between IRP and residues 720–739 of PAP (IRPAP) (Fig. 3B) were expressed and purified in Escherichia coli. A tag of six histidine residues was placed at the amino terminus of both proteins to aid in purification. Both proteins were shown to bind an IRE-containing RNA but not a mutant IRE-containing RNA in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

The carboxy-terminal 20 amino acids of PAP, when tethered to an adenovirus 1 major late intron, stimulate in vitro splicing. (A) The splicing substrates used contained the adenovirus 1 major late intron followed by a 237-nucleotide-long 3′ exon containing a wild-type IRE (TGCTTCAACAGTGCTTGGAC) or a mutant IRE with a single C deletion (TGCTTCAAAGTGCTTGGAC) (Hentze et al. 1987). (B) The recombinant fusion proteins produced in E. coli are the IRP fused at its amino terminus to a histidine tag and the IRP fused at its amino terminus to a histidine tag and at its carboxyl terminus to the 20 carboxy-terminal residues of PAP. (C) Gel mobility shift analysis of interaction between the two recombinant fusion proteins described in B and the wild-type IRE or mutant IRE (IREm) containing RNA. Lanes 1 and 8 show the input RNAs. Fifty nanograms (lanes 2,5,9,12), 100 ng (lanes 3,6,10,13), or 200 ng (lanes 4,7,11,14) of one of the two recombinant proteins was added to the 32P-labeled RNA substrates as indicated. (D) Effect of the addition of the recombinant proteins described in B on the splicing activity of the 32P-labeled wild-type IRE-containing splicing substrate (lanes 1–8) or the 32P-labeled mutant IRE-containing splicing substrate (lanes 9–12). (Lanes 1,9) Input RNAs; (lanes 2,10) splicing in nuclear extract (NE). Increasing amounts of the two recombinant proteins were added to the reaction: 50 ng (lanes 3,6); 100 ng (lanes 4,7); 200 ng (lanes 5,8,11,12). The positions of the precursor RNAs and the products of the reactions are indicated at left.

The effect of IRP and IRPAP on splicing of the two substrate RNAs was tested. Addition of IRPAP to HeLa nuclear extract stimulated splicing of the AdIRE RNA (Fig. 3D, lanes 6–8) but not of the AdIREm RNA (Fig. 3D, lane 12). The specificity of the stimulatory effect was demonstrated further by the lack of stimulatory effect of the addition of IRP to the AdIRE RNA (Fig. 3D, lanes 3–5). Interestingly, the level of splicing stimulation by IRPAP was similar to the AAUAAA-mediated stimulation, supporting the hypothesis that AAUAAA-mediated stimulation of splicing might be mediated by PAP (data not shown; Gunderson et al. 1997).

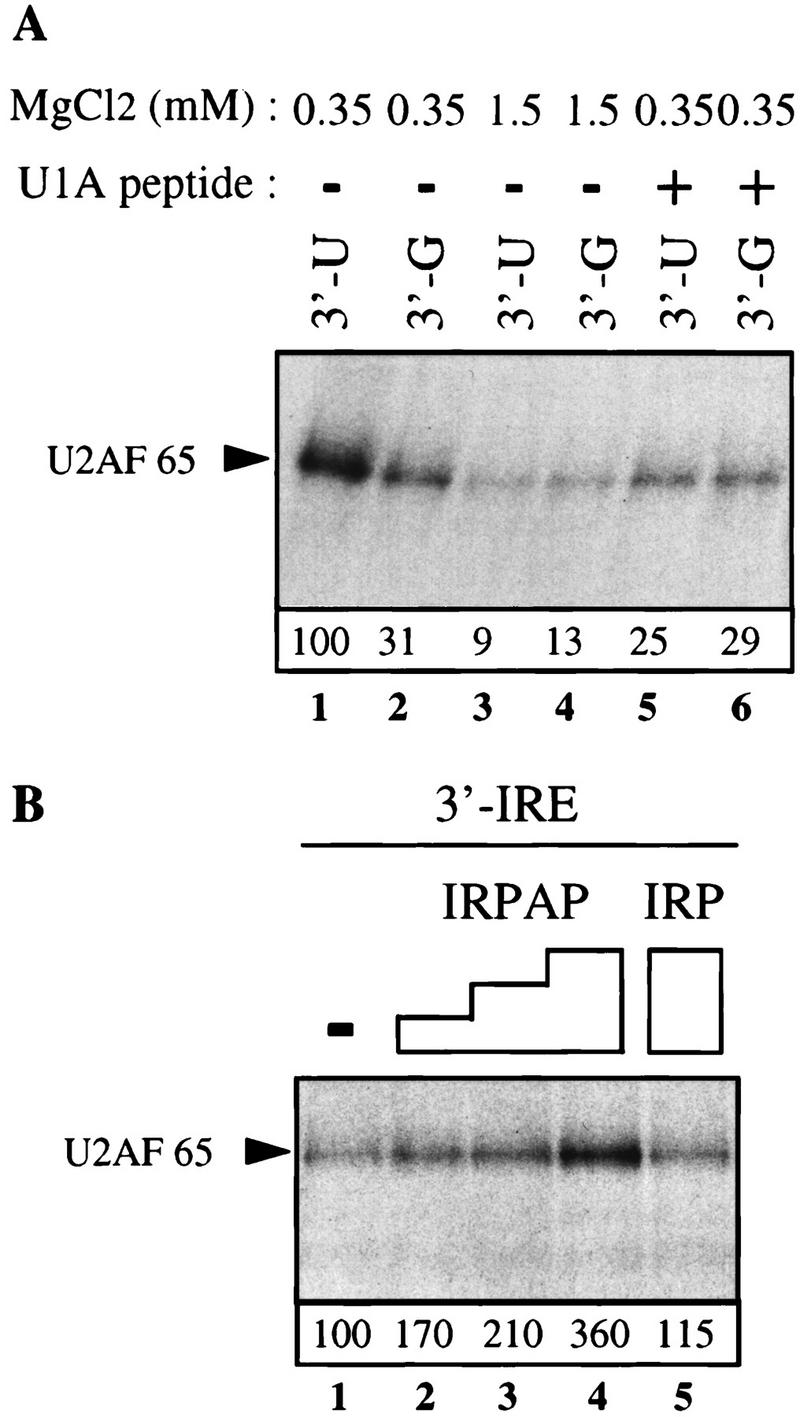

U2AF 65 binding is stimulated similarly to splicing

The effect of addition of the U1A peptide–BSA conjugate, which inhibits coupling between splicing and polyadenylation, on the IRPAP stimulatory effect was examined. Addition of the U1A peptide conjugate abolished the stimulatory effect of IRPAP on splicing of the AdIRE pre-mRNA and had no effect on splicing in the presence of IRP (data not shown). As reported previously (Gunderson et al. 1997), the U1A peptide conjugate had no general inhibitory effect on splicing. Having demonstrated that residues 720–739 of PAP stimulate splicing when tethered to the substrate pre-mRNA, it was of interest to test the effect of these residues and of conditions that prevent coupling between splicing and 3′-end formation on U2AF 65 binding to the upstream 3′ splice site. UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation experiments were therefore performed with the monoclonal antibody against U2AF 65. Addition of the U1A peptide conjugate that blocks coupling (Gunderson et al. 1997) inhibited the AAUAAA-mediated stimulation of binding of U2AF 65 to the 3′ splice site (Fig. 4A), arguing for a role of the carboxyl terminus of PAP in this effect. Similarly, increasing the concentration of Mg2+ to 1.5 mm, which prevents coupling (Niwa and Berget 1991), abolished the AAUAAA effect and the IRPAP effect on U2AF 65 binding (Fig. 4A; data not shown). Addition of IRPAP to the HeLa nuclear extract with the substrate containing a 3′ splice site and a wild-type IRE (3′-IRE) stimulated U2AF 65 binding to this RNA (Fig. 4B, lanes 2–4) whereas addition of IRP itself had little effect on U2AF 65 binding (Fig. 4B, lane 5). Thus, the manner in which the AAUAAA sequence and the RNA-bound PAP increase splicing efficiency appear to be similar in several respects, and both stimulate U2AF 65 binding to the pyrimidine tract of the 3′ splice site.

Figure 4.

Both the AAUAAA sequence and the RNA-bound PAP carboxyl terminus stimulate U2AF 65 binding to the 3′ splice site. (A) RNAs 211 nucleotides long containing the 3′ splice site of the adenovirus I major late intron and the wild-type or mutant adenovirus L3 cleavage/polyadenylation site (3′-U and 3′-G) were incubated in HeLa nuclear extract at 0.35 mm MgCl2 (lanes 2,5,6) or 1.5 mm MgCl2 (lanes 3,4) or in the presence of 0.5 μg of a U1A peptide that uncouples splicing from 3′-end formation (Gunderson et al. 1997). The U1A peptide consists of the sequence ERDRKREKRKPKS, located between residues 103 and 115 of U1A. After UV irradiation, cross-linked polypeptides were immunoprecipitated with the MC3 monoclonal antibody directed against U2AF 65. (B) A 237-nucleotide -long RNA containing the adenovirus I major late intron 3′ splice site and the IRE element was incubated in HeLa nuclear extract supplemented with 50 (lane 2), 100 (lane 3), or 200 (lane 4) ng of the IRPAP recombinant protein or 200 ng of the IRP recombinant protein (lane 5). UV cross-linked proteins were immunoprecipitated with MC3 as in A. Three separate experiments were quantified, and the average values are given below. The 3′-U substrate was set to a value of 100 in A and the 3′ IRE substrate in B.

In an attempt to demonstrate direct U2AF 65–IRPAP interaction we repeated the cross-linking experiment shown in Figure 4B using recombinant U2AF 65 and IRPAP purified from E. coli. Under these conditions we saw no effect of IRPAP on U2AF 65 cross-linking over a broad range of U2AF 65 concentration (data not shown). However, control experiments demonstrated that under these conditions deletion of the polypyrimidine tract from the pre-mRNA substrate did not significantly reduce U2AF 65 cross-linking, indicating that in the absence of nuclear extract, U2AF 65 exhibited strong nonspecific binding to the substrate RNA. We therefore analyzed U2AF 65–PAP interaction using alternative approaches.

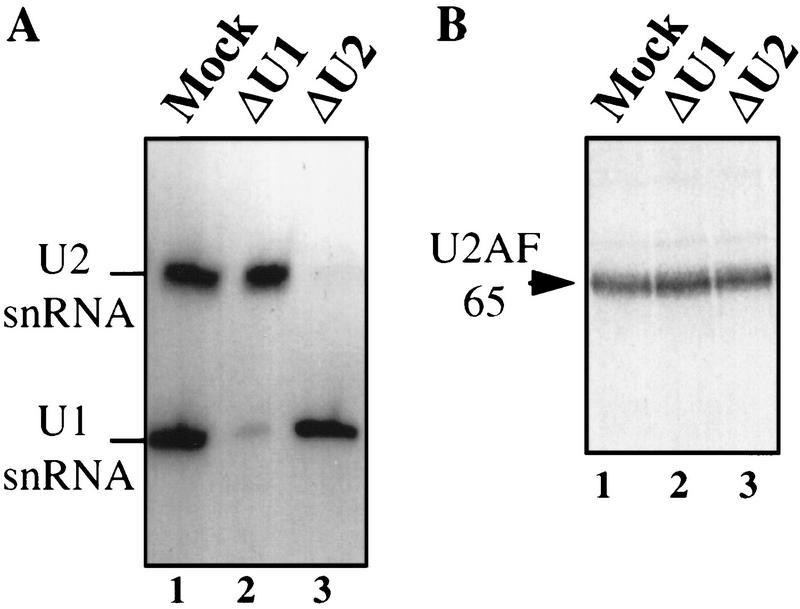

The carboxyl terminus of PAP interacts with U2AF 65 in vitro

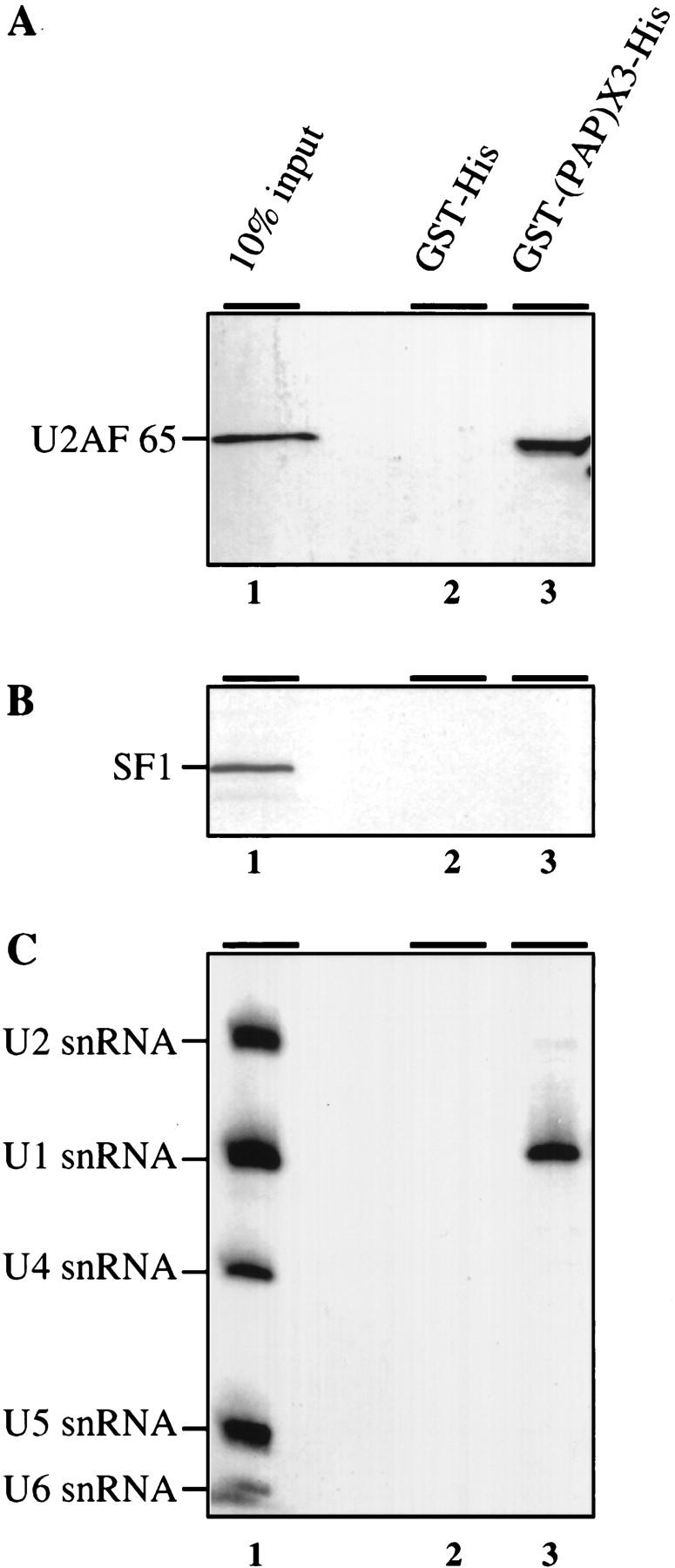

The carboxyl terminus of PAP was shown previously to interact with a domain present in the U1A and U1 70K proteins (Gunderson et al. 1997, 1998). This domain also was proposed to be present in the U2AF 65 protein (Fig. 6C, below; Gunderson et al. 1998). Together with the data presented in this paper, this raised the possibility that PAP could interact directly with U2AF 65.

Figure 6.

The 20 carboxy-terminal residues of PAP interact specifically with residues 17–47 of U2AF 65. Five micrograms of E. coli-produced GST–His fusion proteins were bound to glutathione–agarose beads and used in binding assays with [35S] methionine labeled U1A, SF1-H, SF1–Bo, and U2AF 65 proteins (A) or various [35S]methionine-labeled U2AF 65 deletion mutants (B). (C) Comparison of the U1A and U1 70K motifs that bind to PAP (Gunderson et al. 1998) with the U2AF 65 sequence between residues 17 and 47.

To investigate this, a GST fusion protein interaction assay was employed. A fusion protein containing three copies of the 20-amino-acid carboxy-terminal segment of PAP inserted between the GST coding sequence and a carboxy-terminal six histidine tag was constructed [GST–(PAP)X3–His]. The resulting protein was expressed in E. coli and purified by virtue of the two tags. A GST–His fusion protein with no insert was also purified.

These two proteins were first used to try to enrich U2AF 65 from HeLa cell nuclear extract (Fig. 5A). Western blotting of the bound protein fraction with a monoclonal antibody against U2AF 65 shows that U2AF 65 bound to GST–(PAP)X3–His. This interaction was specific as the SF1/BBP protein did not bind (Fig. 5B). Given the presence of a PAP carboxy-terminal binding domain in U1 70K protein, we used U1 snRNP interaction as a further specificity control. Although U2, U4, U5, or U6 snRNPs (Fig. 5C) were not found in the GST–(PAP)X3–His bound fraction, U1 snRNP did bind to the carboxy-terminal region of PAP (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

The 20 carboxy-terminal residues of PAP interact specifically with U2AF 65 in HeLa nuclear extracts. GST pull-down experiments with a recombinant GST–His fusion protein or a GST–His fusion protein containing three copies of the last carboxy-terminal 20 residues of PAP (GST–(PAP)X3–His; Gunderson et al. 1997). Five micrograms of the E. coli-produced GST–His fusion proteins were bound to glutathione–agarose beads and incubated with 200 μg of HeLa nuclear extract in splicing conditions. Bound proteins were eluted, loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and vizualized by Western blot. (A) U2AF 65 binding; (B) SF1/mBBP binding; (C) bound RNAs were eluted, purified and loaded on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel before Northern blot analysis with U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNA probes. (Lane 1) Ten percent of the binding reaction inputs are loaded. Pull-down with the GST–His or the GST–(PAP)X3–His fusion proteins are in lanes 2 and 3. U2AF 65, SF1, and the various snRNAs are indicated at left.

The fusion proteins were used next in a binding assay with [35S]methionine-labeled U2AF 65 protein produced by in vitro transcription–translation. U1A protein was included as a negative control, as it cannot bind to PAP as a monomer. Two splice variants of the human SF1/mBBP protein, SF1-H and SF1–Bo (Krämer et al. 1998), were also tested. Efficient binding of U2AF 65 to the GST–(PAP)X3–His fusion protein was detected (Fig. 6A, lane 12). However, U2AF 65 was not bound to the GST–His control protein (Fig. 6A, lane 8). Moreover, the U1A, SF1-H, and SF1–Bo proteins did not bind to either the GST–(PAP)X3–His or to the GST–His fusion proteins. These results provide further evidence that the carboxyl terminus of PAP can interact with U2AF 65.

As mentioned previously, a database search for PAP-binding motifs (Gunderson et al. 1998) had identified U2AF 65 as a putative PAP-interacting protein. Therefore, deletion mutants of the region of U2AF 65 that exhibits similarity with the U1A or U1 70K regions able to interact with PAP (Fig. 6C) were generated. Deletion of the hypothetical PAP-interacting region in U2AF 65 (Δ17–27) drastically reduced binding to the GST–(PAP)X3–His fusion protein (Fig. 6B). Two other U2AF 65 mutants (Δ17–47 and Δ29–48) that remove parts of the region show reduced binding to the GST–(PAP)X3–His fusion protein (Fig. 6B). This may indicate that there is a third region elsewhere in U2AF 65 that can cooperate with either of the deleted sequences to allow weak PAP binding. Alternatively, unlike the U1A or U1 70K cases, a single binding site in U2AF 65 might have a high enough affinity to allow weak binding to PAP on its own. Nevertheless, the results show that the 20-amino-acid carboxy-terminal fragment of PAP interacts with an amino-terminal region of U2AF 65 spanning residues 17–47, that is, with the sequences predicted to interact with PAP on the basis of their similarity to U1A and U1 70K (Gunderson et al. 1998).

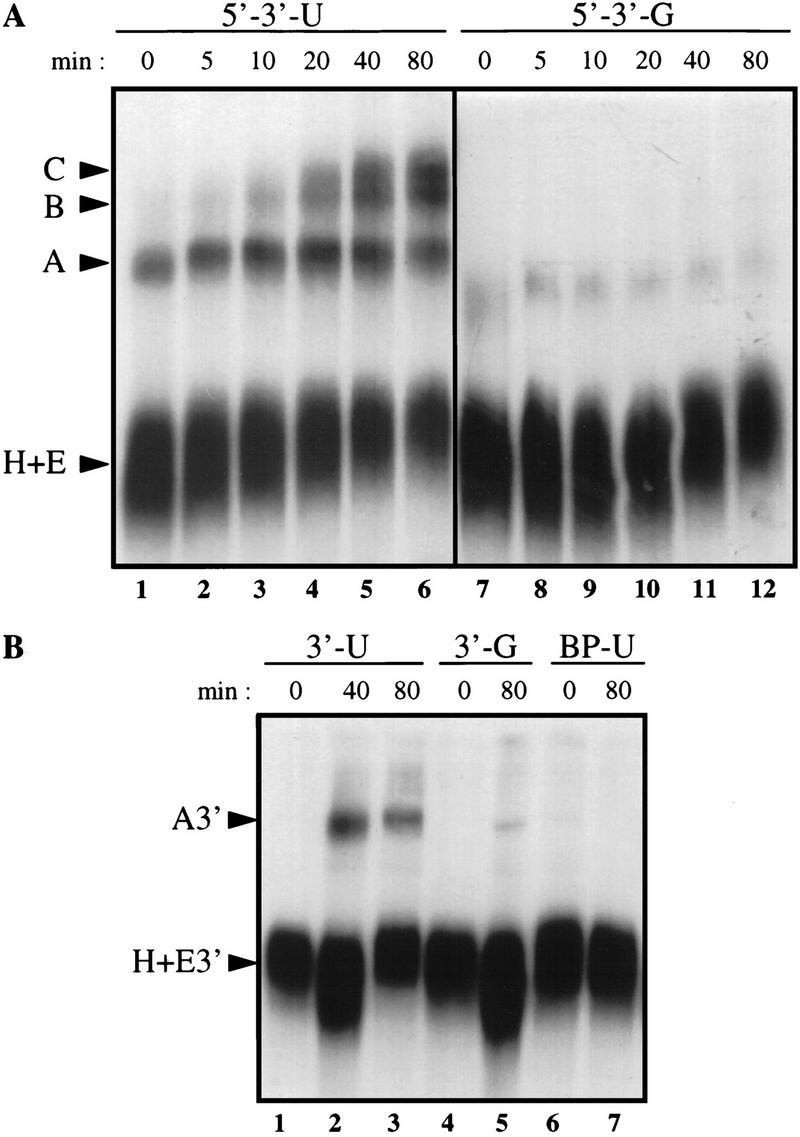

U1 snRNP is not required for the stimulation of U2AF 65 binding

Because U1 snRNP is known to interact with both U2AF 65 during splicesome assembly and with PAP during the inhibition of polyadenylation (see introductory section) and because U1 snRNP has been implicated previously in the coupling process (Wassarman and Steitz 1993), we wanted to test whether U1 snRNP might be necessary, in crude extract, to mediate the effect of the 3′-end formation signal on splicing efficiency. To this end, we depleted HeLa nuclear extract of either U1 or, as a control, U2 snRNP using 2′-O methylated oligonucleotides (Barabino et al. 1990) (Fig. 7A). As expected, neither of the depleted extracts could support splicing (data not shown). We then carried out the U2AF 65 cross-linking assay using the 3′-U RNA as a probe. No difference in cross-linking efficiency was seen when mock-depleted extract was compared with U1- or U2-depleted extract (Fig. 7B). U1 snRNP is therefore not required to mediate the effect of the 3′-end formation signal on U2AF 65 binding.

Figure 7.

Depletion of U1 snRNP does not block the AAUAAA-mediated stimulation of U2AF 65. (A) Antisense affinity depletion of U1 and U2 snRNP from HeLa nuclear extract (Barabino et al. 1990). RNAs recovered from mock-depleted extract (lane 1), U1 snRNP-depleted extract (lane 2), or U2 snRNP-depleted extract (lane 3) were analyzed by Northern hybridization with U1 and U2 snRNA-specific probes. U1 and U2 snRNAs are indicated. (B) UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation, as in Fig. 2, was performed with the depleted extracts, as indicated at top. The 3′-U RNA substrate was used.

Discussion

We report here on the mechanism by which a cleavage/polyadenylation site stimulates splicing of an adjacent upstream intron, a process usually referred to as coupling (Berget 1995). Three main conclusions are drawn: (1) The carboxy-terminal 20 amino acids of PAP, when tethered to the pre-mRNA downstream of an intron, stimulate in vitro splicing; (2) the AAUAAA sequence and the carboxyl terminus of PAP exert their stimulatory effect on splicing via enhancement of the binding of U2AF 65 to the pyrimidine tract of the 3′ splice site; and (3) PAP and U2AF 65 are able to interact directly with each other through the PAP carboxyl terminus. This supports a model for coupling in which PAP, after incorporation into the CPSF–CStF complex that associates with the cleavage/polyadenylation site, can interact with U2AF 65 and help tether this factor to the pyrimidine tract of the adjacent 3′ splice site, thereby stimulating splicing. This interaction therefore provides a mechanistic explanation for the long-standing observation that cleavage/polyadenylation and splicing are often, but not always, coupled (Moore and Sharp 1985; Hashimoto and Steitz 1986; Niwa et al. 1990, 1992; Niwa and Berget 1991; Nesic et al. 1993, 1995; Wassarman and Steitz 1993; Nesic and Maquat 1994; Kuersten et al. 1997). It also provides insight into the mechanism by which the 3′-terminal exon is recognized, supporting the proposals of the exon definition model (Berget 1995).

Molecular interactions coupling 3′-end processing and splicing

We describe an interaction between the last 20 amino acids of PAP and the U2AF 65 protein involved in the recognition of the 3′ splice site. The carboxyl terminus of PAP was reported previously to interact with the U1A and U1 70K proteins (Gunderson et al. 1997, 1998), two constituents of U1 snRNP. U2AF 65, U1A, and U1 70K were proposed to belong to a family of proteins containing a common domain of interaction with the carboxyl terminus of PAP (Gunderson et al. 1998). The data presented here provide strong support for this hypothesis, as deletion of the U2AF 65 sequences that are related to the U1A and U1 70K PAP interaction domains prevents PAP–U2AF 65 interaction. The demonstration here that the predicted interaction between PAP and U2AF 65 does occur and has functional consequences suggests that it will be of value to investigate the other predicted PAP-interacting proteins (Gunderson et al. 1998). U1A, U1 70K, and U2AF 65 could all, in principle, be involved in the coupling between cleavage/polyadenylation and splicing. However, as the PAP–U1A interaction requires two copies of the U1A protein (Gunderson et al. 1997) and the U1 snRNP contains only one U1A protein, it is very unlikely that the U1A protein is a partner of PAP in the coupling process. U1 70K protein contains two separate domains that are capable of PAP interaction (Gunderson et al. 1998). The carboxyl terminus of PAP was shown to interact directly and specifically with purified U1 snRNP (Gunderson et al. 1998) and with U1 snRNP in HeLa nuclear extract (Fig. 5). U1 snRNP could therefore, via PAP binding, be involved in the coupling process, as suggested previously on the basis of data showing weak association of U1 snRNP with 3′-terminal exons (Wassarman and Steitz 1993). However, we found that depletion of U1 snRNP from HeLa nuclear extract did not lead to a block of the AAUAAA-mediated stimulation of U2AF 65 binding to the pyrimidine tract of an intron substrate lacking the 5′ splice site (Fig. 7). This argues against an essential role of U1 snRNP in the coupling process and instead indicates that U2AF 65 interaction with PAP is sufficient to couple splicing and cleavage/polyadenylation. It is possible that U1 snRNP could in some way increase the efficiency with which PAP and U2AF 65 enter into their interaction.

3′-Terminal exon definition

3′-Terminal exon definition (Berget 1995) involves the coordinate recognition of a 3′ splice site with the adjacent downstream cleavage and polyadenylation signals. It seems likely that the requirement for this coordinate recognition is not universal and will depend on the intrinsic strength of the processing signals at either end of the 3′-terminal exon. Therefore, regulation of the utilization of a 3′-terminal exon might occur by modulating the recognition of either of its borders.

A number of studies have shown that alternate poly(A) site selection can be associated with alternative 3′ splice site choice. For instance, the alternative processing of the pre-mRNA encoding calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide (CT/CGRP) occurs by inclusion of a 3′-terminal exon (exon 4) that is located within a six exon primary transcript. Inclusion of exon 4 requires an intron enhancer that activates the use of the exon 4 poly(A) site (Lou et al. 1995, 1996). Our results suggest that increased recognition of the exon 4 poly(A) site would in turn stimulate binding of U2AF 65 to the very weak 3′ splice site of exon 4, thereby favoring selection of the alternative exon.

Parallels between the AAUAAA-mediated and exon splicing enhancer-mediated stimulation of splicing

Splicing signals on pre-mRNAs are often very weak, and this can be a prerequisite for their regulation. To support the precise and efficient recognition of weak splicing signals, communication between the signals is required (see introductory section). In addition, specific exon sequences capable of strongly stimulating the recognition of weak splice sites were discovered and designated exon splicing enhancers (for review, see Hertel et al. 1997). The function of an exon splicing enhancer is to stabilize the interaction between splicing components and splice sites. This enhancement is dependent, on one hand, on various protein factors that bind to the RNA sequences forming the exon splicing enhancer, and on the other hand, on protein factors that establish a network of interactions between the exon splicing enhancer-bound proteins and the splicing machinery. These factors are thought to consist principally of a group of proteins containing a domain rich in arginine and serine residues, called SR proteins (for review, see Fu 1995; Manley and Tacke 1996; Valcárcel and Green 1996). SR proteins have been shown in several cases to establish bridging contacts between the exon splicing enhancer and an adjacent upstream 3′ splice site (Hertel et al. 1997).

In this study, we demonstrate that a cleavage/polyadenylation site stimulates splicing in a manner analogous to exon splicing enhancers, by promoting the recognition of the adjacent upstream 3′ splice site. The magnitude of the stimulation of U2AF 65 binding seen here is similar in magnitude to the effects observed with either an exon splicing enhancer (Zuo and Maniatis 1996) or with a downstream 5′ splice site (Hoffman and Grabowski 1992). However, the set of protein factors that mediate the enhancement effect are different. In the case of the cleavage/polyadenylation site, the machinery that forms the 3′-end, via its CPSF and CStF components, recognizes the site and the PAP bound to this complex fulfills the role of the SR proteins by establishing communication between the enhancer site and the 3′ splice site. In conclusion, cleavage/polyadenylation sites have a function in addition to their role in 3′-end processing. They also act as 3′-terminal exon splicing enhancers. PAP seems to have a direct role in this function via its interaction with the 3′ splice site-binding protein U2AF 65.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructions

Plasmids were constructed by standard cloning procedures (Sambrook et al. 1989). pBS 5′ → 3′-U and pBS 5′ → 3′-G are identical to pBSAd211 and pBSAd212 (Gunderson et al. 1997). pBS 3′-U and pBS 3′-G were derived, respectively, from pBS 5′ → 3′-U and pBS 5′ → 3′-G by deletion of a 382-nucleotide-long sequence surrounding the 5′ splice site. pBS BP-U, pBS PYRmut-U, and pBS PYRdown-U are all derived from pBS 3′-U. The wild-type adenovirus I major late 3′ branchpoint sequence CUUAUCC was mutated to CGGGUCC in pBS BP-U; the sequences mutated in pBS PYRmut-U and pBS PYRdown-U are in Figure 2. pBSAdIRE and pBSAdIREmut were constructed by inserting in the BglII site (located 52 nucleotides downstream of the adenovirus I major late intron) of pBSAd212, two oligonucleotides corresponding to the IRE or the IRE mutant sequences (deletion of a single C residue; Hentze et al. 1987) (IRE, TGCTTCAACAGTGCTTGGAC; IRE mutant, TGCTTCAAAGTGCTTGGAC). The vector encoding the IRPAP fusion protein was constructed by inserting the coding region corresponding to the last carboxy-terminal residues of bovine PAP (residues 720–739) at the carboxyl terminus of the IRP coding sequence of pT7-7 IRP (Gray et al. 1993). The plasmids encoding the GST–His or GST–(PAP)X3–His fusion proteins were described (Gunderson et al. 1997). pGEM4–SF1 HL1 and pGEM4–SF1–Bo were provided by Angela Krämer (Arning et al. 1996). pGEM U2AF 65 was a gift of Juan Valcárcel (Valcárcel et al. 1996). This plasmid was used to generate the three human U2AF 65 deletion mutants (deletion of residues 17–47, 17–27, or 30–47).

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

The IRP and IRPAP fusion proteins were produced in E. coli and purified according to Gray et al. (1993). The two proteins GST–His and GST–(PAP)X3–His were expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity by consecutive glutathione agarose and Ni2+–NTA chromatography steps.

Splicing reactions

Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells by the procedure of Dignam et al. (1983). Substrate RNAs were transcribed by T3 RNA polymerase and capped with m7GpppG. Reactions were as described in Gunderson et al. (1997) and were performed with 0.35 mm MgCl2.

Native gel analysis of splicing complexes

The different pre-mRNAs were incubated in splicing conditions for the indicated times. A portion of each splicing reaction was adjusted to 0.5 mg/ml heparin, incubated for 10 min at 30°C, and separated by electrophoresis through a nondenaturing 4% (80:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) polyacrylamide gel run in 50 mm Tris-glycine (Konarska and Sharp 1986). Electrophoresis was carried out at 250 V for 5 hr at 4°C. 32P-Labeled RNP complexes were detected by autoradiography.

IRP EMSAs

EMSAs contained 32P-labeled RNAs, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 150 mm KCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 10 units of RNasin (Promega), 1 μg of BSA, and 0.5 μg of yeast tRNA in 10 μl. Recombinant IRP or IRPAP was added last. Reactions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature prior to loading on a 6% (60:1) polyacrylamide gel run in Tris–Borate–EDTA buffer.

UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation

HeLa cell nuclear extract was incubated for 5 min with 32P-labeled RNAs under splicing conditions except that ATP and creatine phosphate were omitted from the reaction. The reaction mixtures were then irradiated on ice with UV light (254 nm) in a Stratalinker (Stratagene) at 0.4 J/cm2 at 10-cm distance. Fifty units of RNase T1 was added, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. SDS–gel loading buffer was added and the samples were boiled for 2 min before fractionation on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. For immunoprecipitation of UV cross-linked proteins, 20 μl of the RNase T1-treated samples were diluted in 200 μl of IP2 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 0.05% NP-40), precleared, and mixed with either 7 μl of anti-CstF 64K monoclonal antibody, 5 μl of anti-U2AF 65 monoclonal antibody, or 10 μl of anti-SF1 polyclonal antibody. The mixtures were allowed to rotate for 1 hr at 4°C. Protein G beads (for CstF 64 and U2AF 65) or protein A beads (for SF1) were added to the mixtures, and incubations continued for 1 hr at 4°C. After extensive washing of the beads, the bound proteins were eluted in SDS-loading buffer.

GST-binding assays

These experiments were carried out as described by Xiao and Manley (1997). Briefly, 5 μg of purified GST–His or GST–(PAP)X3–His proteins were bound to 30 μl of glutathione-agarose beads in NETN buffer (20 mm Tris at pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 mm EDTA) for 30 min at 4°C, followed by three washes with 1 ml of NETN buffer. HeLa nuclear extracts were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with GST–His-loaded glutathione beads. After extensive washing (three to five times), bound proteins were eluted by boiling for 2 min in SDS-loading buffer. Eluted proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE before electroblotting onto Protran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). Blots were probed with the anti-U2AF 65 or anti-SF1 antibodies and anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, respectively, coupled to peroxidase. Signals were detected using ECL (Amersham). To analyze interactions with snRNAs, beads were washed and treated with proteinase K (100 μg/ml) at 37°C for 20 min, followed by phenol chloroform extraction. RNAs were recovered by ethanol precipitation and loaded onto a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (8 m urea). The gel was electroblotted to GeneScreen membranes. Blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled antisense U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNA probes in hybridization solution (6× SSC, 40% formamide, 0.5% SDS, 2× Denhardt's solution, 100 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA) at 42°C overnight and then washed four times with 6× SSC, 0.1% SDS. Signals were detected by autoradiography.

U1A, SF1-H, SF1–Bo, U2AF 65, or the various U2AF 65 deletion mutants were produced by in vitro translation using TNT rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) and labeled with [35S] methionine. For each binding reaction, 2–5 μl of translation mixture was used and assays were performed in 200 μl of NETN buffer at 4°C. Beads were then washed five times, treated with 10 μg/ml of RNase A at room temperature for 30 min, and washed again. Protein elution was performed by adding SDS-loading buffer to the beads. Eluted proteins were resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE. Gels were fixed and dried, and labeled proteins were visualized by fluorography.

U1 snRNP depletion

HeLa nuclear extracts were depleted of U1 or U2 snRNP with biotinylated antisense 2′-O methyl RNA oligonucleotides (U1, 5′-GCCAGGUAAGUAU-3′; U2, 5′-GGCCGAGAAGCGAU-3′) complementary to specific regions of U1 and U2 snRNAs, as described previously (Barabino et al. 1990). Depleted extracts were checked after recovery of the RNAs from the nuclear extracts by proteinase K treatment followed by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. RNAs were run on urea–polyacrylamide gels and detected by Northern blotting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juan Valcárcel for very helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Angela Krämer for the SF1 cDNAs, Clinton MacDonald for the 3A7 monoclonal antibody against CStF 64K, Matthias Hentze for the IRP cDNA, and Juan Valcárcel for the U2AF 65 cDNA, the MC3 monoclonal antibody, and the SF1 antibody. S.V. was the recipient of an EMBO long-term postdoctoral fellowship and of an EEC Training and Mobility of Researchers fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL mattaj@embl-heidelberg.de; FAX 49 6221 387 518.

References

- Abovich N, Rosbash M. Cross-intron bridging interactions in the yeast commitment complex are conserved in mammals. Cell. 1997;89:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias JA, Peterson SR, Dynan WS. Promoter-dependent phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II by a template-bound kinase. Association with transcriptional initiation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8055–8061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arning S, Grüter P, Bilbe G, Krämer A. Mammalian splicing factor SF1 is encoded by variant cDNAs and binds to RNA. RNA. 1996;2:794–810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabino SML, Blencowe BJ, Ryder U, Sproat BS, Lamond AI. Targeted snRNP depletion reveals an additional role for mammalian U1 snRNP in spliceosome assembly. Cell. 1990;63:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauren G, Belikov S, Wieslander L. Transcriptional termination in the Balbiani ring 1 gene is closely coupled to 3′-end formation and excision of the 3′-terminal intron. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2759–2769. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berget SM. Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2411–2414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund JA, Chua K, Abovich N, Reed R, Rosbash M. The splicing factor BBP interacts specifically with the pre-mRNA branchpoint sequence UACUAAC. Cell. 1997;89:781–787. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund JA, Abovich N, Rosbash M. A cooperative interaction between U2AF65 and mBBP/SF1 facilitates branchpoint region recognition. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:858–867. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelens WC, Jansen EJ, van Venrooij WJ, Stripecke R, Mattaj IW, Gunderson SI. The human U1 snRNP-specific U1A protein inhibits polyadenylation of its own pre-mRNA. Cell. 1993;72:881–892. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90577-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara MD, Reed R. A two-step mechanism for 5′ and 3′ splice-site pairing. Nature. 1995;375:510–513. doi: 10.1038/375510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho EJ, Takagi T, Moore CR, Buratowski S. mRNA capping enzyme is recruited to the transcription complex by phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:3319–3326. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colot HV, Stutz F, Rosbash M. The yeast splicing factor Mud13p is a commitment complex component and corresponds to CBP20, the small subunit of the nuclear cap-binding complex. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1699–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke C, Alwine JC. The cap and the 3′ splice site similarly affect polyadenylation efficiency. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2579–2584. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty SM, Fortes P, Izaurralde E, Mattaj IW, Gilmartin GM. Participation of the nuclear cap binding complex in pre-mRNA 3′ processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:11893–11898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XD. The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA. 1995;1:663–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XD, Maniatis T. The 35-kDa mammalian splicing factor SC35 mediates specific interactions between U1 and U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles at the 3′ splice site. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:1725–1729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama-Carvalho M, Krauss RD, Chiang L, Valcárcel J, Green MR, Carmo-Fonseca M. Targeting of U2AF65 to sites of active splicing in the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:975–987. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin GM, McDevitt MA, Nevins JR. Multiple factors are required for specific RNA cleavage at a poly(A) addition site. Genes & Dev. 1988;2:578–587. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NK, Quick S, Goossen B, Constable A, Hirling H, Kuhn LC, Hentze MW. Recombinant iron-regulatory factor functions as an iron-responsive-element-binding protein, a translational repressor and an aconitase. A functional assay for translational repression and direct demonstration of the iron switch. Eur J Biochem. 1993;218:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson SI, Beyer K, Martin G, Keller W, Boelens WC, Mattaj IW. The human U1A snRNP protein regulates polyadenylation via a direct interaction with poly(A) polymerase. Cell. 1994;76:531–541. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson SI, Vagner S, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Mattaj IW. Involvement of the carboxyl terminus of vertebrate poly(A) polymerase in U1A autoregulation and in the coupling of splicing and polyadenylation. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:761–773. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson SI, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Mattaj IW. U1 snRNP inhibits pre-mRNA polyadenylation through a direct interaction between U1 70K and poly(A) polymerase. Mol Cell. 1998;1:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto C, Steitz JA. A small nuclear ribonucleoprotein associates with the AAUAAA polyadenylation signal in vitro. Cell. 1986;45:581–591. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze MW, Kuhn LC. Molecular control of vertebrate iron metabolism: mRNA-based regulatory circuits operated by iron, nitric oxide, and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:8175–8182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze MW, Caughman SW, Rouault TA, Barriocanal JG, Dancis A, Harford JB, Klausner RD. Identification of the iron-responsive element for the translational regulation of human ferritin mRNA. Science. 1987;238:1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.3685996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel KJ, Lynch KW, Maniatis T. Common themes in the function of transcription and splicing enhancers. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BE, Grabowski PJ. U1 snRNP targets an essential splicing factor, U2AF 65, to the 3′ splice site by a network of interactions spanning the exon. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:2554–2568. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Ohno M, Sakamoto H, Shimura Y. Effect of the cap structure on pre-mRNA splicing in Xenopus oocyte nuclei. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:1472–1479. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Lewis J, McGuigan C, Jankowska M, Darzynkiewicz E, Mattaj IW. A nuclear cap binding protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 1994;78:657–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Lewis J, Gamberi C, Jarmolowski A, McGuigan C, Mattaj IW. A cap-binding protein complex mediating U snRNA export. Nature. 1995;376:709–712. doi: 10.1038/376709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka N, Ohno M, Kangawa K, Tokoro Y, Shimura Y. Cloning of a complementary DNA encoding an 80 kilodalton nuclear cap binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3861–3865. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.19.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka N, Ohno M, Moda I, Shimura Y. Identification of the factors that interact with NCBP, an 80 kDa nuclear cap binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3638–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarska MM, Sharp PA. Electrophoretic separation of complexes involved in the splicing of precursors to mRNAs. Cell. 1986;46:845–855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer A, Quentin M, Mulhauser F. Diverse modes of alternative splicing of human splicing factor SF1 deduced from the exon-intron structure of the gene. Gene. 1998;211:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuersten S, Lea K, MacMorris M, Spieth J, Blumenthal T. Relationship between 3′-end formation and SL2-specific trans-splicing in polycistronic Caenorhabditis elegans pre-mRNA processing. RNA. 1997;3:269–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laybourn PJ, Dahmus ME. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase IIA occurs subsequent to interaction with the promoter and before the initiation of transcription. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13165–13173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Izaurralde E, Jarmolowski A, McGuigan C, Mattaj IW. A nuclear cap-binding complex facilitates association of U1 snRNP with the cap-proximal 5′ splice site. Genes & Dev. 1996a;10:1683–1698. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Görlich D, Mattaj IW. A yeast cap binding protein complex (yCBC) acts at an early step in pre- mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996b;24:3332–3336. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.17.3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Yang Y, Cote GJ, Berget SM, Gagel RF. An intron enhancer containing a 5′ splice site sequence in the human calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:7135–7142. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Gagel RF, Berget SM. An intron enhancer recognized by splicing factors activates polyadenylation. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:208–219. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald CC, Wilusz J, Shenk T. The 64-kilodalton subunit of the CstF polyadenylation factor binds to pre-mRNAs downstream of the cleavage site and influences cleavage site location. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6647–6654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley JL, Tacke R. SR proteins and splicing control. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1569–1579. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken S, Fong N, Yankulov K, Ballantyne S, Pan G, Greenblatt J, Patterson SD, Wickens M, Bentley DL. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature. 1997a;385:357–361. doi: 10.1038/385357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken S, Fong N, Rosonina E, Yankulov K, Brothers G, Siderovski D, Hessel A, Foster S, Shuman S, Bentley DL. 5′-Capping enzymes are targeted to pre-mRNA by binding to the phosphorylated carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes & Dev. 1997b;11:3306–3318. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud S, Reed R. A functional association between the 5′ and 3′ splice site is established in the earliest prespliceosome complex (E) in mammals. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:1008–1020. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CL, Sharp PA. Accurate cleavage and polyadenylation of exogenous RNA substrate. Cell. 1985;41:845–855. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic D, Maquat LE. Upstream introns influence the efficiency of final intron removal and RNA 3′-end formation. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:363–375. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic D, Cheng J, Maquat LE. Sequences within the last intron function in RNA 3′-end formation in cultured cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3359–3369. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic D, Zhang J, Maquat LE. Lack of an effect of the efficiency of RNA 3′-end formation on the efficiency of removal of either the final or the penultimate intron in intact cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:488–496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer KM, Roth MB. Transcription units as RNA processing units. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:3279–3285. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Berget SM. Mutation of the AAUAAA polyadenylation signal depresses in vitro splicing of proximal but not distal introns. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:2086–2095. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Rose SD, Berget SM. In vitro polyadenylation is stimulated by the presence of an upstream intron. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:1552–1559. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, MacDonald CC, Berget SM. Are vertebrate exons scanned during splice-site selection? Nature. 1992;360:277–280. doi: 10.1038/360277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rain JC, Rafi Z, Rhani Z, Legrain P, Krämer A. Conservation of functional domains involved in RNA binding and protein-protein interactions in human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae pre-mRNA splicing factor SF1. RNA. 1998;4:551–565. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robberson BL, Cote GJ, Berget SM. Exon definition may facilitate splice site selection in RNAs with multiple exons. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:84–94. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosbash M, Séraphin B. Who′s on first? The U1 snRNP-5′ splice site interaction and splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin B, Zamore PD, Green MR. A factor, U2AF, is required for U2 snRNP binding and splicing complex assembly. Cell. 1988;52:207–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Staknis D, Reed R. Direct interactions between pre-mRNA and six U2 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins during spliceosome assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1994a;14:2994–3005. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— SR proteins promote the first specific recognition of Pre-mRNA and are present together with the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in a general splicing enhancer complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1994b;14:7670–7682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcárcel J, Green MR. The SR protein family: Pleiotropic functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder CW, Gunderson SI, Jansen EJ, Boelens WC, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Mattaj IW, van Venrooij WJ. A complex secondary structure in U1A pre-mRNA that binds two molecules of U1A protein is required for regulation of polyadenylation. EMBO J. 1993;12:5191–5200. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman KM, Steitz JA. Association with terminal exons in pre-mRNAs: A new role for the U1 snRNP? Genes & Dev. 1993;7:647–659. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao SH, Manley JL. Phosphorylation of the ASF/SF2 RS domain affects both protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions and is necessary for splicing. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:334–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore P D, Patton JG, Green MR. Cloning and domain structure of the mammalian splicing factor U2AF. Nature. 1992;355:609–614. doi: 10.1038/355609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo P, Maniatis T. The splicing factor U2AF35 mediates critical protein–protein interactions in constitutive and enhancer-dependent splicing. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]