Abstract

Myxococcus xanthus fruiting body development is induced by amino acid limitation. The decision to grow or develop is established by the RelA-dependent stringent response and A-signaling. We identified two new members of this regulatory hierarchy, socE and the C-signaling gene csgA. SocE depletion arrests growth and induces sporulation under conditions that normally favor growth as well as curtailing DNA and stable RNA synthesis, inhibiting cell elongation, and inducing accumulations of the stringent nucleotides ppGpp and pppGpp [(p)ppGpp]. This system separates C-signaling, which does not occur under these conditions, from CsgA enzyme activity. Amino acid substitutions in the CsgA coenzyme binding pocket or catalytic site eliminate growth arrest. relA mutation also eliminates growth arrest. Eleven pseudorevertants selected for growth following SocE depletion contained mutations in csgA or relA. These results suggest that CsgA induces the stringent response and while SocE inhibits it. Unlike the csgA mutant, wild-type and socE csgA cells maintained high levels of (p)ppGpp throughout development. We suggest that CsgA maintains growth arrest throughout development to divert carbon from A-signaling and other sources into developmental macromolecular synthesis.

Keywords: M. xanthus, development, fruiting body formation, cell–cell signaling, growth control, stringent response

Fruiting body development of Myxococcus xanthus is induced when amino acid depletion forces the cells to decide whether to grow or develop. Central to the decision is the stringent response, which shares many features with that of Escherichia coli (for review, see Cashel et al. 1996). When ribosomes stall because of lack of charged tRNA, the ribosome-associated protein RelA synthesizes guanosine-5′-diphosphate–3′-diphosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine-5′-triphosphate–3′-diphosphate (pppGpp) (Harris et al. 1998; Manoil and Kaiser 1980b, 1980c), collectively abbreviated (p)ppGpp. Fruiting body development is also regulated by at least five extracellular signals, A, B, C, D, and E (Hagen et al. 1978; Downard et al. 1993). Elimination of any signal disrupts development within the first 6 hr and inhibits fruiting body morphogenesis, spore differentiation, and developmental gene expression (for review, see Dworkin 1996; Shimkets 1999).

The stringent response activates A-signaling (for review, see Kaiser 1996; Plamann and Kaplan 1999), which begins with the secretion of proteases that hydrolyze cell surface proteins to generate amino acids (Kuspa et al. 1992; Plamann et al. 1992). Because Myxococcus cells themselves are the protease substrates, the amino acid concentration rises in direct proportion to cell density. Several of these amino acids serve as a quorum signal. Having ascertained that a quorum of starved cells is available, development continues. However, a potential problem emerges. The amino acids generated by A-signal proteases reach an extracellular concentration high enough to restore growth. They also provide a limited resource to fuel development. So the cell must change its physiology to funnel these amino acids to development rather than growth. The work described in this paper suggests that the C-signaling protein CsgA and the SocE protein help divert the carbon flow into developmental proteins by maintaining a stringent response even in the presence of A-signal amino acids.

The only known member of the C-signaling system is CsgA (for review, see Shimkets and Kaiser 1999). Addition of CsgA to buffer on top of csgA cells restores fruiting body formation and developmental gene expression (Kim and Kaiser 1990a, 1991). However, CsgA is a member of the short chain alcohol dehydrogenase family that uses the coenzyme NAD(P)(H) (Lee et al. 1995). The proposed catalytic activity may be intracellular, as it is not clear that there is a pool of extracellular coenzyme. To complicate matters, CsgA also has a role in motility. It is essential for rippling, a multicellular behavior in which cells move in rhythmic oscillations (Shimkets and Kaiser 1982a; Sager and Kaiser 1994) and activates a sensory transduction pathway, Frizzy, that is structurally and functionally similar to the chemotaxis system of enteric bacteria (Sogaard-Anderson and Kaiser 1996). The role of the CsgA enzyme activity in these processes remains unknown, as does the chemical nature of the substrate.

In an attempt to define the biochemical function(s) of CsgA more clearly, Rhie and Shimkets (1989) isolated suppressor mutations in which the developmental requirement for CsgA has been bypassed. The socE537 mutation is a transposon insertion that results in loss of socE function yet restores development to csgA null mutants without restoring C-signaling (Rhie and Shimkets 1989; E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.). SocE is a highly basic protein with little similarity to proteins in sequence databases (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.). Attempts to transfer the socE null allele to csgA+ strains failed, suggesting that SocE is essential for growth in csgA+ cells (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.). In this work we placed socE under control of a light-inducible promoter and discovered that SocE depletion arrests growth and induces sporulation and a stringent response, even in the presence of amino acids, provided functional copies of csgA and relA are present. This system allows the putative CsgA enzyme activity to be isolated from C-signaling and studied independently. The results suggest that CsgA and SocE have opposing roles in the decision to grow or develop through a modified stringent response.

Results

SocE is required for growth of csgA+ cells

The original socE mutation was a Tn5 insertion that suppressed the csgA developmental defect without restoring C-signaling. Attempts to move this mutation into a csgA+ mutant were unsuccessful (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.). To determine whether a socE mutation is lethal in csgA+ cells we expressed socE using the M. xanthus light-inducible promoter pcarQRS (abbreviated phv). This promoter is inactive in the dark and becomes highly active in blue light (Hodgson 1993). A FspI–NcoI fragment carrying the 5′ portion of socE, which does not encode essential carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequences (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.) was inserted downstream of phv to create pGC28. The phv–socE construct was electroporated into wild-type M. xanthus cells in the presence of light to stimulate expression of socE. Homologous recombination between the wild-type socE allele and the light-inducible construct produced a merodiploid, LS2125, containing a 3′ deletion of the native copy of socE, under control of its own promoter, and a light-inducible full-length copy of socE. Southern blotting confirmed the presence of the predicted recombination event (data not shown).

Expression of phv–socE was examined in the light and the dark. LS2125 was cultured in CYE broth in the light. When cells reached early log phase one of two replicate cultures was wrapped in foil to block the light, terminating socE expression. socE mRNA was quantified by hybridization with a probe complementary to the 3′ NcoI–HindIII fragment of socE. By 1 hr after the shift to the dark socE mRNA was undetectable, whereas the level of socE mRNA in light-grown cultures remained constant (data not shown).

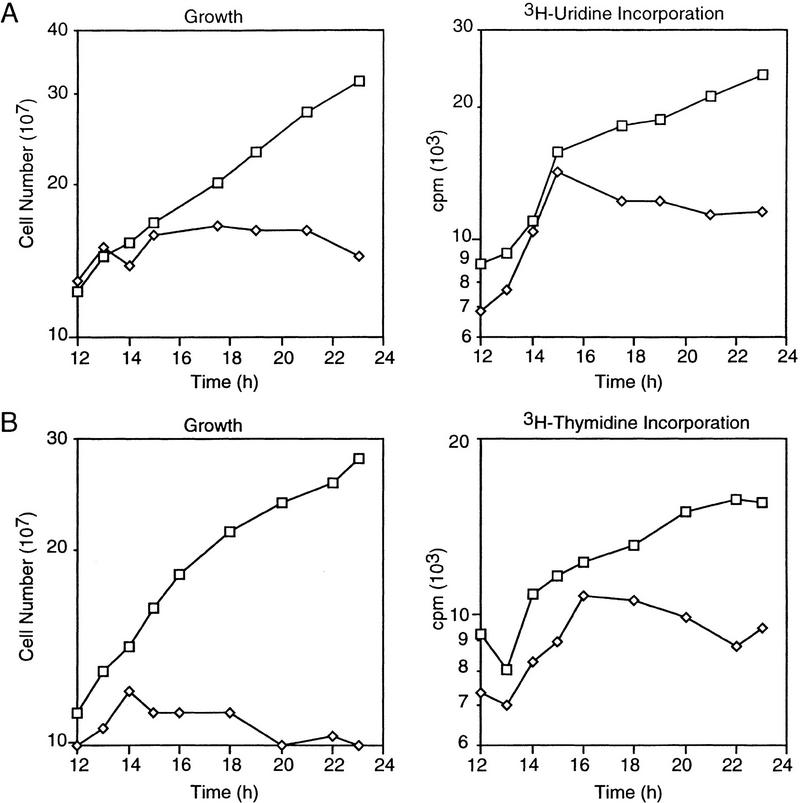

The phenotype of SocE-depleted cells was compared under light and dark conditions using a similar approach. Aliquots were removed for cell and spore quantitation over 216 hr (Fig. 1). Growth of LS2125 ceased 12–15 hr (∼2.5 generations) after elimination of socE expression in spite of the presence of excess nutrients. The cells undergo 2.5 doublings before growth arrest, which would reduce the SocE concentration about sixfold in the absence of protein turnover. Dark-grown cells began to sporulate at 144 hr, and by 168 hr nearly all cells had become spherical, refractile spores. The addition of light to SocE-depleted cells at any point prior to sporulation allowed growth to resume (data not shown). In contrast, LS2125 cells incubated in the light continued to grow until they reached stationary phase at ∼36 hr and did not form spores through the course of the experiment (168 hr). Wild-type cells also exhibited normal growth and did not form spores in the light or the dark under these conditions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of socE depletion on cell growth. At time 0 light-grown cultures of LS2125 cells were shifted to darkness (solid symbols) or allowed to continue growing in the light (open symbols). Cell number (squares) and spore number (circles) were determined by direct counts. After ∼2.5 generations the SocE-depleted cells ceased growing, and by 168 hr most had sporulated.

During fruiting body development only a fraction of the cells become spores. About 15% of the cells remain outside the fruiting bodies, becoming peripheral rods (O'Connor and Zusman 1991b). O'Connor and Zusman (1991a) have proposed that peripheral rods emerge because of the secretion of aggregation and sporulation inhibitors. An even larger portion of the population dies during fruiting body development (Wireman and Dworkin 1975). These alternate fates are bypassed in this SocE-depletion assay, as virtually all of the cells differentiate into spores. However, the spore yield during fruiting body development of SocE-depleted cells is comparable to that of wild-type and socE csgA mutants, suggesting that suppression of these alternate developmental fates is largely due to the environmental conditions of the assay.

Spore structure

The formation of myxospores in liquid growth medium is reminiscent of a technique for artificially inducing sporulation. Dworkin and Gibson (1964) discovered that the addition of 0.5 m glycerol to growing M. xanthus cells induces sporulation in the absence of starvation and multicellular development. Since this discovery it has been demonstrated that glycerol-induced spores differ from fruiting body spores in a number of ways: (1) The rate of respiration is higher in glycerol-induced spores than it is in fruiting body spores (Dworkin and Niederpruem 1964); (2) glycerol-induced spores lose refractility when incubated in phosphate buffer, unlike fruiting body spores (Ramsey and Dworkin 1968); (3) glycerol-induced spores have a thin spore coat that is deficient in spore coat proteins C (McCleary et al. 1991), S (Inouye et al. 1979), and U (Gollop et al 1991); and (4) glycerol-induced spores lack the polyphosphate storage particles formed by protein W in fruiting body spores (Otani et al. 1998).

Transmission electron microscopy was used to determine if the spores produced by SocE depletion were more similar to glycerol-type or fruiting body-type spores. The spores of SocE-depleted LS2125 were similar to wild-type fruiting body spores, having thick spore coats and protein W inclusions (data not shown). This approach represents the first description of a method to obtain fruiting body-like spores in liquid growth media. LS2125 spores were unable to germinate in the light or dark, on CYE agar or in CYE broth (data not shown). Perhaps SocE is necessary to initiate germination and phv cannot be activated by light in the dormant spore.

Macromolecular synthesis during growth arrest

Measurement of cell length affords an easy assessment of progress through the cell division cycle. Newly divided cells are short and nearly double in length during the cell cycle. Septa appear at 0.90 generation, and separation occurs at 1.0 generation. Growth-arrested cells varied in length from short nascent cells to long septating cells (data not shown). Most cells were within the normal range of lengths and widths. Furthermore, newly arrested cells exhibited a similar range of sizes to those that had been arrested for several days. It appears that growth is not arrested at a single point in the cell division cycle but that cell elongation ceases.

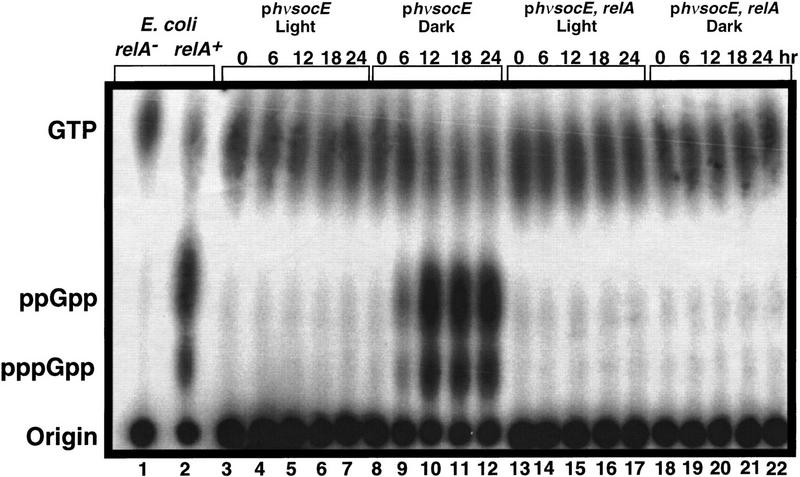

Cells synthesize RNA throughout the cell division cycle (Zusman and Rosenberg 1971). RNA synthesis was assessed by incorporation of [3H] uridine into trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-insoluble material. After the shift to dark, LS2125 continued to grow and incorporate [3H] uridine in parallel with wild-type DK1622 up to 15 hr, ceased growth, and reduced RNA synthesis (Fig. 2A). Because stable RNA accounts for ∼80% of the total RNA and sporulation-specific genes become active after growth cessation, it is likely that the decline in transcription primarily reflects a decline in stable RNA synthesis rather than a complete inhibition of RNA production. At least some development-specific, CsgA-dependent genes are transcribed under these conditions. ΩLS234 is expressed at levels comparable to those observed during fruiting body development. ΩDK4531 is expressed at 35% the level observed during fruiting body development, and ΩDK4435 is expressed at ∼13% (data not shown). These results suggest that transcription under these conditions is highly selective.

Figure 2.

Nucleic acid synthesis following SocE depletion. At time 0 light-grown cultures were transferred to the dark and incubated. DK1622 (wild type, □); LS2125 (phv–socE, ⋄). (A) Growth (left) and [3H]-uridine incorporation into RNA (right). (B) Growth (left) and [3H] thymidine incorporation into DNA (right).

Chromosome replication extends from 0.02 to 0.81 generations covering the majority of the cell cycle (Zusman and Rosenberg 1970). Incorporation of [3H] thymidine into TCA-insoluble material was used to assess DNA synthesis. Growth and [3H] thymidine incorporation by LS2125 cells incubated in the dark paralleled that of DK1622 up until ∼16 hr, at which time growth of LS2125 ceased and [3H] thymidine incorporation declined (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that SocE depletion inhibits both DNA and RNA synthesis.

SocE depletion leads to an increase in (p)ppGpp levels

Accumulation of (p)ppGpp is correlated with a decline in the growth rate, and inhibition of DNA and stable RNA synthesis in E. coli (for review, see Cashel et al. 1996). Two enzymes can synthesize (p)ppGpp—RelA and SpoT. RelA is ribosome associated and has only synthetic activity. When E. coli is starved for amino acids, uncharged tRNA causes translational pausing, which stimulates phosphorylation of GTP or GDP in a reaction that requires ATP, ribosomes, mRNA, RelA, and uncharged tRNA. SpoT has (p)ppGpp 3′-pyrophosphohydrolase activity in addition to synthetic activity that is not associated with ribosomes.

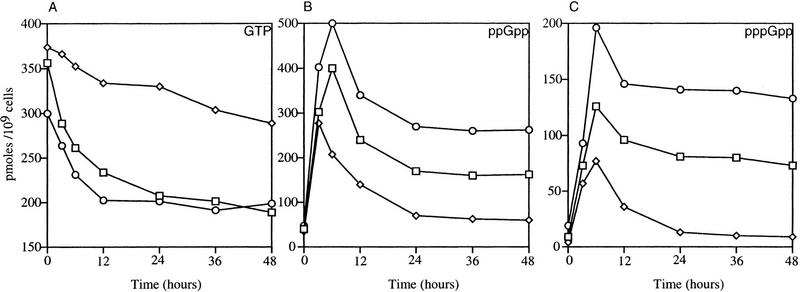

(p)ppGpp pools were measured to determine whether growth inhibition following SocE depletion is due to induction of the stringent response. LS2125 cells were grown in the light in CYE broth containing [32P] orthophosphate to label the pools to steady state. Labeled cultures were then diluted into identical 32P-containing CYE and placed in the light for continued growth or in the dark to eliminate ectopic socE expression. Aliquots were removed at regular intervals for 24 hr, and the guanine nucleotides separated by thin layer chromatography (TLC). Light-grown cells maintained a relatively constant level of GTP and low levels of (p)ppGpp (Fig. 3). GTP, ppGpp, and pppGpp pools were quantified and are relatively constant in light-grown cells in spite of the fact that the cells entered stationary phase (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Measurement of the guanine nucleotide pools. phv-socE (LS2125) and phv-socE, relA (LS2162) were grown in CYE containing 32P-orthophospate in the light or in the dark. The guanine nucleotide pools were extracted at the times indicated across the top (hr) and separated by one-dimensional TLC. Into each lane, 15,000 cpm was loaded. (Left) Guanine nucleotides were identified by their rf values using starved E. coli relA (lane 1) and relA+ (lane 2) strains as controls.

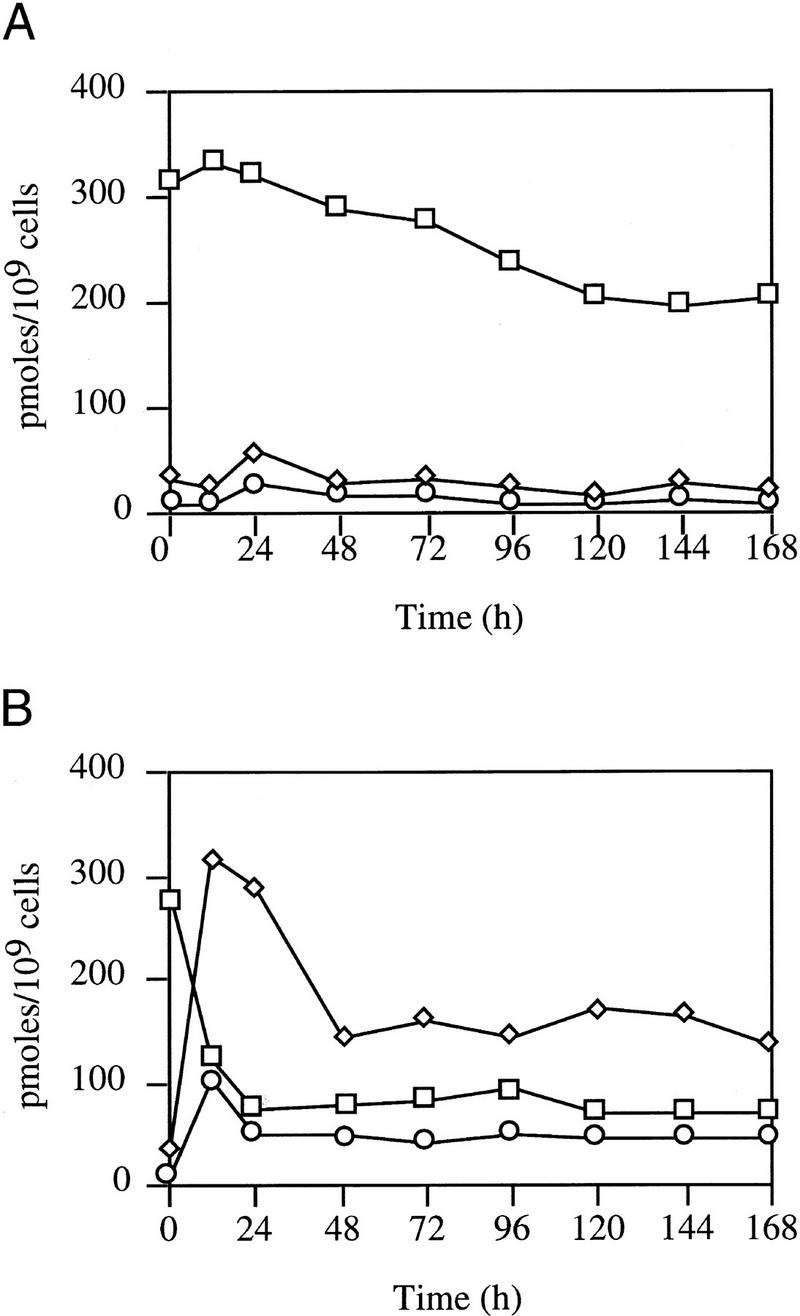

Figure 4.

Guanine nucleotide pool sizes. LS2125 (phv-socE) was incubated in CYE containing [32P]-orthophosphate in the light (A) or dark (B). Guanine nucleotide pools were extracted at the indicated times, separated by one-dimensional TLC, and quantified using a PhosphorImager 400S and ImageQuant software. Nucleotide levels are expressed as pmoles of nucleotide per 109 cells. (□), GTP; (⋄) ppGpp; (○) pppGpp.

Following shift to the dark there is a dramatic increase in the ppGpp pool and a more modest increase in pppGpp (Fig. 3). Cells showed a marked increase in (p)ppGpp levels by 6 hr, and levels peaked at 12 hr when macromolecular synthesis declined (Fig. 4). Concomitant with this increases in the (p)ppGpp pool was a comparable decrease in the GTP pool. The pool sizes of ppGpp and pppGpp then decrease about two-fold but remain much higher than the levels seen in light-grown cells. The experiment was concluded at 168 hr when sporulation begins because the spores are resistant to nucleotide extraction by this method.

To determine whether induction of the stringent nucleotides is essential for growth arrest, the light-inducible socE construct was introduced into a strain containing a relA mutation (Harris et al.1998). The relA mutation prevented both growth inhibition and sporulation following SocE depletion (data not shown), as well as the accumulation of (p)ppGpp (Fig. 3). The RelA-dependent production of the stringent nucleotides in the SocE depletion assay is surprising, as the cells are present in a liquid medium with amino acid levels that could support a 10-fold increase in cell number (Fig. 1).

(p)ppGpp synthesis is CsgA-dependent but C-signal independent

The ppGpp pool sizes of csgA+ SocE-depleted cells were compared with wild-type strain DK1622, a csgA socE double mutant (LS537), and a csgA mutant (LS523) 12 hr after a shift to the dark. Synthesis of ppGpp was observed only in csgA+ SocE-depleted cells and is correlated with growth arrest and sporulation (Table 1). These results argue that CsgA stimulates ppGpp synthesis in the absence of SocE.

Table 1.

Guanine nucleotide pool sizes

| Genotype

|

pmoles/109 cells

|

Growth

|

Sporulation

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTP

|

ppGpp

|

|||

| csgA+ socE+ | 521 ± 62 | 38 ± 21 | + | − |

| csgA− socE+ | 506 ± 73 | 29 ± 11 | + | − |

| csgA+ socE−a | 103 ± 18 | 318 ± 37 | − | + |

| csgA− socEb | 478 ± 53 | 43 ± 14 | + | − |

Cells were made socE− through the ectopic expression system, as transduction of socE537 into csgA+ cells was not possible.

Cells contained the socE537 mutation.

It is unlikely that C-signaling occurs under these conditions, as the cells are dispersed at low cell density in liquid growth medium to prevent contact-dependent exchange of the C-signal. Furthermore, the growth medium is not conditioned by secretion of a chemical signal required for growth arrest or sporulation. At 0, 12, 24, 120, 144, and 168 hr after transfer to the dark the LS2125 culture supernatant was filtered through 0.22-μm filters. Light-grown LS2125 cells were resuspended in the conditioned medium. Cultures incubated in the presence of the conditioned media continued to grow unabated until stationary phase and sporulation did not occur. Those shifted to the dark showed no change in the number of cell divisions preceding growth arrest, the time to initiation of sporulation, or the fraction of cells sporulating compared to control cultures. It appears then that C-signaling does not occur under these conditions.

One possibility is that the putative catalytic function of CsgA is intracellular where it induces the stringent response. In support of this idea, all csgA mutations that disrupt fruiting body development also prevent growth arrest and sporulation in response to SocE depletion, arguing for a direct relationship between the developmental function of CsgA and the phenotype observed in the SocE depletion assay. CsgA exhibits remarkable similarity with short chain alcohol dehydrogenases (Lee et al. 1995), which have a core of conserved catalytic residues (Persson et al. 1991). The csgA1098 allele produces a protein (T6A) that is unable to bind NAD+ in vitro and unable to restore development to csgA mutants when added exogenously (Lee et al. 1995). SocE depletion in the presence of this allele, or in the presence of two other alleles with mutations in the coenzyme binding region [csgA1099 (R10A) and csgA1152 (D57N) (Lee et al. 1995)], does not arrest growth or induce sporulation in SocE-depleted cells (data not shown). S135 and K155 are essential for catalytic activity in all known members of this family. Amino acid substitutions S135T (csgA1153) and K155R (csgA1155) fail to arrest growth or induce sporulation in SocE-depleted cells (data not shown). Three other csgA alleles that inhibit development also prevent growth arrest and sporulation in SocE-depleted cells including csgA653 (A157V), csgA269 (Tn5 lac insertion), and csgA278 (Tn5 lac insertion). These results have separated C-signaling from CsgA enzyme activity and argue that growth arrest and spore induction are mediated by internal CsgA.

Suppression of growth arrest

One can isolate pseudorevertants that are restored for growth by simply plating SocE-depleted cells on growth medium in the dark. The spontaneous reversion frequency is ∼3 × 10−9 revertants/cell, suggesting that mutation of only a few genes can restore growth. Eleven independent suppressors were isolated, eight following Tn5-132 mutagenesis and three following UV mutagenesis. Because RelA and CsgA are already known to be required for growth arrest, we examined whether growth arrest could be restored by addition of functional relA or csgA genes to the pseudorevertants. Eight were complemented by csgA and three were complemented by relA. Southern hybridization confirmed that LS2133 and LS2134 contain Tn5 insertions in relA and that L2130, LS2131, LS2132, LS2135, LS2136, and LS2137 contain Tn5 insertions in csgA (data not shown). Finally, inverse PCR was performed on chromosomal DNA from each of the relA-complemented strains using Tn5-specific primers. The resultant PCR products were cloned and sequenced to define the precise insertion sites in relA. The insertion sites predicted by Southern hybridization were confirmed by the results of the PCR analysis (data not shown).

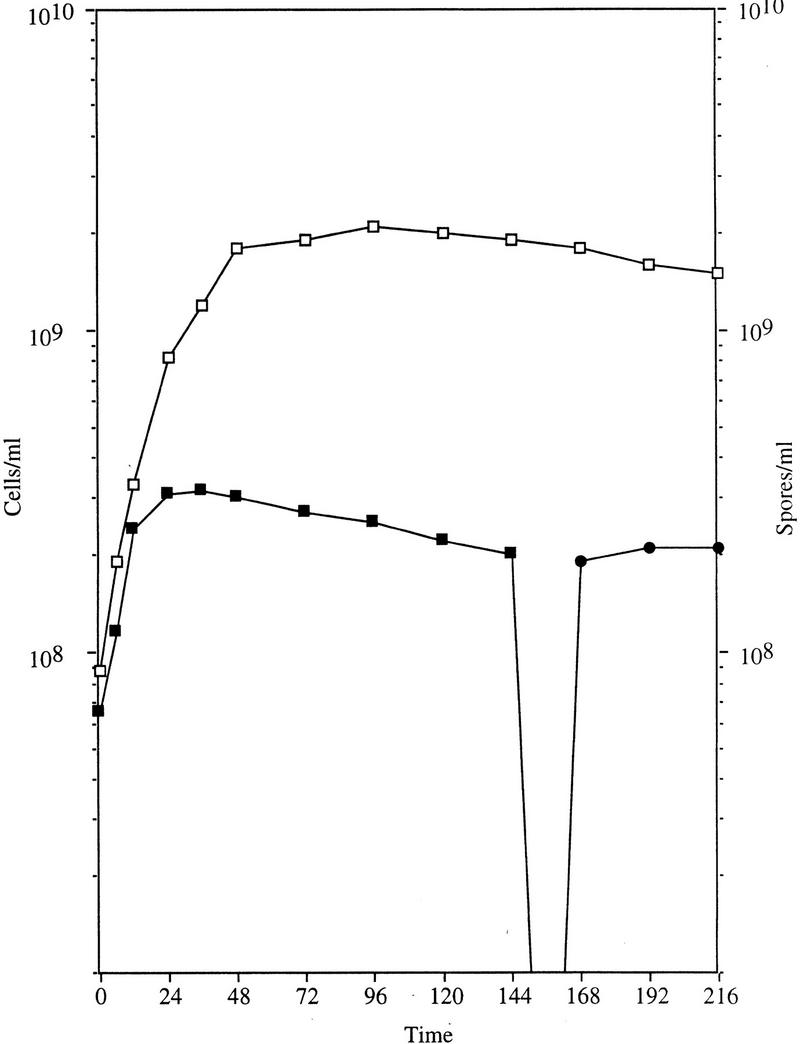

Developmental (p)ppGpp levels

We wondered whether the purpose of the CsgA-dependent stringent response was to maintain cells in a growth-arrested state as a means of diverting the A-signal amino acids into developmental macromolecular synthesis. This hypothesis predicts that csgA mutants are unable to sustain the stringent response through the period of A-signaling and the cells consequently revert to vegetative growth. The guanine nucleotide pools of csgA mutant LS523 were examined during development and compared to those of wild-type strain DK1622 and a csgA socE double mutant (LS537). The csgA mutant initiated the stringent response following nutrient deprivation although the (p)ppGpp pools were only half those of the wild type. These results show that csgA is not essential for the stringent response following amino acid limitation and confirm the qualitative study of LaRossa et al. (1983). Most strikingly, csgA mutants were unable to sustain the response; the (p)ppGpp pool decreases to vegetative levels by 24 hr (Fig. 5). Both the attenuated response and the decline to vegetative levels are consistent with the notion that csgA mutants do not divert A-signal amino acids to developmental macromolecular synthesis. This notion is supported by the observation that csgA developmental gene expression arrests during the period of A-signaling ∼6 hr into the developmental pathway (Kroos and Kaiser 1987).

Figure 5.

Guanine nucleotide pools during development. M. xanthus strains were allowed to develop in submerged culture and were harvested at the indicated times. Guanine nucleotides were extracted, separated by TLC, and quantified. Nucleotide levels are expressed as pmoles of nucleotide per 109 cells. (□) wild-type DK1622; (⋄) csgA mutant LS523; (○) csgA socE strain LS537.

The socE mutation compensates for the csgA mutation by increasing the concentration of stringent nucleotides and sustaining the stringent response throughout development (Fig. 5). Interestingly the socE csgA mutant develops significantly faster than the wild type (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.) which is correlated with higher levels of (p)ppGpp. These results suggest that SocE attenuates the stringent response.

Discussion

Because fruiting body development is an alternative to growth, most of the genetic work with M. xanthus has involved isolating developmental mutants that necessarily grow well. This strategy has been enormously successful but would not reveal those regulatory genes that commit a cell to the vegetative pathway, as mutations in genes that repress development would be expected to induce sporulation in rich media. We have identified the first repressor of development—SocE. SocE depletion in otherwise wild-type cells leads to growth arrest, inhibition of DNA and stable RNA synthesis, production of (p)ppGpp, and induction of sporulation in liquid growth media.

Curiously, SocE depletion initiates a RelA-dependent stringent response in the presence of extracellular amino acids. The results are consistent with the idea that the relative levels of SocE and CsgA determine cell fate during times when amino acid levels become an unreliable indicator of environmental resources. The catabolism of proteins to fuel development may fool the cell into resuming growth unless growth is arrested. This rationale is based on work done on the stringent response and A-signaling, which precede C-signaling during development. During the initial response to amino acid limitation, cells induce a RelA-dependent stringent response and accumulate (p)ppGpp (Manoil and Kaiser 1980a,b; Singer and Kaiser 1995; Harris et al. 1998). The stringent response inhibits socE transcription (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.), stimulates csgA transcription (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.), and induces A-signaling (Singer and Kaiser 1995). A-signaling begins with the secretion of proteases that hydrolyze cell surface proteins to generate amino acids (Kuspa et al. 1992; Plamann et al. 1992). An increase in the ratio of CsgA to SocE, which is initiated by RelA-dependent transcriptional regulation of these two genes, arrests growth thereby assuring that this precious resource is used exclusively for development. Consistent with this notion, csgA mutants mount a developmental stringent response that is quantitatively diminished relative to the wild type and is not sustained throughout development. These results fit the temporal order of events in that CsgA mutants are blocked ∼6 hr into the developmental program (Kroos and Kaiser 1987) during the period of A-signaling.

We propose that C-signaling involves contact-dependent exchange of CsgA as a monitor of cell density. In this model nascent CsgA is exported from the cell, both to prevent premature growth arrest and sporulation as well as to act as a cell density and alignment sensor. As cell density and alignment increase, C-signal transmission becomes more efficient (Kim and Kaiser 1990b). If extracellular CsgA is internalized while SocE is simultaneously depleted, intracellular CsgA levels would achieve levels high enough to halt growth by sustaining the stringent response throughout development and induce sporulation. If that density decreases to the point where CsgA is no longer exchanged, then the higher SocE levels would direct growth instead of development.

Because deletion of socE restores development to csgA mutants in the absence of C-signaling the principle function of CsgA may be to overwhelm or inhibit residual SocE. It is unlikely that CsgA directly titers out SocE to induce development, as ectopic expression of csgA did not stimulate development under conditions of nutrient excess where the levels of SocE are high (Li et al. 1992). The most likely possibility is that CsgA limits the level of an aminoacyl tRNA. It is likely that SocE inhibits RelA. Expression of socE in relA− E. coli leads to a rapid decline in cell viability as cells enter stationary phase (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.). This decline in viability is greatly reduced in relA+ strains and can be reduced further by over expressing E. coli relA. Consistent with this suggestion is the induction of early developmental gene expression by the ectopic expression of relA under nutritional conditions that repress development via a high level of SocE (Singer and Kaiser 1995).

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

E. coli and M. xanthus strains are listed in Table 2. M. xanthus cultures were grown in CYE broth (1% Casitone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.1% MgSO4 · 7H2O, 10 mm MOPS pH 7.6) or on CYE agar (CYE broth with 1.5% Difco agar) at 32°C. When light was required, cultures were placed 4 inches below 20 W, wide-spectrum fluorescent bulbs generating about 7000 lux. E. coli cultures were grown at 37°C in L broth. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 200 μg/ml ampicillin; 50 μg/ml kanamycin; 12.5 μg/ml tetracycline; 250 μg/ml trimethoprim; for M. xanthus or 20 μg/ml for E. coli.

Table 2.

Strains

| Strains

|

Genotype

|

Reference or derivation

|

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| CF1648 | wild type | Cashel (1994) |

| CF1651 | relAΔ251 | Cashel (1994) |

| XL1 | F′::Tn10, proA+B+, lacIq, (lacZ)M151, recA1, endA1, gyrA96, thi, hsdR17, supE44, relA1, lac | Bullock et al. (1987) |

| M. xanthus | ||

| DK1622 | wild type | Shimkets and Kaiser (1982a) |

| LS203 | csgA653 | Shimkets and Asher (1988) |

| LS429 | csgA205, ΩDK4531, ΩLS429Tp | Li and Shimkets (1993) |

| LS523 | csgA205 | Shimkets and Asher (1988) |

| LS537 | csgA205, socE537 | Rhie and Shimkets (1989) |

| LS2105 | csgA653, socE537 | this work |

| LS2125 | phv–socE (KmR) | this work |

| LS127 | phv–socE (TcR) | this work |

| LS2133 | phv–socE, relA2133::Tn5-132 | this work |

| LS2134 | phv–socE, relA2134::Tn5-132 | this work |

| LS2162 | phv–socE, relA527 | this work |

Generalized transduction

Strains were constructed by generalized transduction using Mx4 (Campos et al. 1978). relA− transductants arose at a frequency several orders of magnitude lower than expected by generalized transduction in this and another study (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.). Nevertheless, the relA mutation used in this work was confirmed by Southern hybridization (data not shown), and analyses of the guanine nucleotide pools in LS2162 confirm that it is unable to synthesize (p)ppGpp (Fig. 3). The reason for the reduced transduction frequency is not known. relA− strains were encountered regularly upon selection for growth of SocE-depleted cells.

Fruiting body formation

Log-phase cells grown in CYE broth were washed twice with TPM buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 8 mm MgSO4, 1 mm K2HPO4) and resuspended to 5 × 109 cells/ml in TPM buffer. Aliquots (20 μl) were spotted onto TPM agar (TPM buffer plus 1.5% Difco agar) and incubated at 32°C. Plates were incubated at 50°C for 2 hr and spores were dispersed by sonic disruption. Spores were quantified by phase-contrast microscopy in a Petroff–Hauser counting chamber. Viable spores were quantified by diluting spore preparations in TPM buffer, mixing the dilutions in CYE soft agar (CYE broth plus 0.7% Difco agar), and plating these onto CYE agar to allow spore germination.

Construction of a light-inducible socE allele

Vector pDAH328 (a gift from D. Hodgson) contains the light-inducible promoter phv, which is activated in the presence of blue light (Hodgson 1993). The socE gene was excised from pGC25 with FspI and NcoI to yield a socE allele that is truncated at the 3′ end. The NcoI end of the 1.4-kb fragment was extended with Klenow fragment and ligated into the SmaI site of pDAH328. A plasmid containing the insert in the correct orientation was digested with XhoI and EcoRI to excise the entire phv-socE fusion, and this fragment was ligated into XhoI/EcoRI-digested pBGS18 (Spratt et al. 1986). The resulting plasmid, pGC37, was electroporated into M. xanthus strain DK1622 in the light selecting for kanamycin resistance. Southern hybridization verified the structure of the electroporants. Specifically, chromosomal DNA from the parent, DK1622, and an electroporant was digested with FspI and PstI and probed with the 500-bp NcoI–HindIII fragment of socE. Cells containing a wild-type copy of socE produce a 2.8-kb fragment, whereas the merodiploid produces a 4.3-kb fragment, as the phv–socE allele has lost the 5′ FspI site during insertion of phv.

Analysis of (p)ppGpp levels

Analysis of guanine nucleotide levels was performed using a modification of the method described by Manoil and Kaiser (1980a). Cells were labeled in CYE broth containing 100 μCi/ml [32P] orthophosphate and 5 μm cold orthophosphate carrier for 12 hr, using light induction of socE expression when necessary. After preincubation, cells were diluted to 107 cells/ml in the same medium and incubated in the light or the dark as required. For developmental studies 400 μl of CYE medium containing 100 μCi/ml [32P] orthophosphate and 5 μm cold orthophosphate carrier was placed in each well of a 24-well cell culture dish and 5 × 108 cells added. These were incubated overnight at 32°C to allow biofilm formation. Biofilms were washed gently four times with MC7 buffer (10 mm MOPS, 1 mm CaCl2) and overlaid with MC7 plus 100 μCi/ml [32P] orthophosphate and 5 μm cold orthophosphate carrier. An entire biofilm was harvested at each time point, and cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 50 μl of MC7 buffer. Each sample was mixed with 50 μl of 13 m formic acid. Guanine nucleotides were released by two freeze–thaw cycles and separated by one-dimensional TLC on PEI cellulose plates (Sigma) with 1.5 m KH2PO4 (Cashel 1994). Spots were visualized and quantified using a PhosphorImager 400S (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuant version 1.0 (Molecular Dynamics).

Electron microscopy

Spores were purified on sucrose step gradients (Inouye et al. 1979) and prepared as described previously (Shimkets and Kaiser 1982b). Spores were embedded in Spurr resin, and thin sections were cut with a Sorvall MT2-B Ultra Microtome and viewed with a Jeol 100 CX transmission electron microscope.

DNA and RNA synthesis

Strains were grown in CYE broth with light to mid-log phase. These cultures were then diluted into fresh CYE broth containing 25 μCi/ml [3H] uridine (Amersham) for measuring RNA synthesis or 25 μCi/ml [3H] thymidine for measuring DNA synthesis. Upon transfer to the labeling medium, cultures were wrapped in foil. Growth of these cultures was followed using a Klett meter and 200-μl samples were removed for analysis at intervals for 24 hr. Samples were mixed with 600 μl of ice cold 10% TCA and filtered through Whatman GF/A glass fiber filters. Filters were washed three times each with 2 ml of ice-cold 10% TCA and once with 2 ml of ice-cold 100% ethanol. Filters were dried and counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Measurement of socE mRNA

Cells were grown in 100 ml of CYE broth in the light. Dark-grown cultures were wrapped in foil in the same incubator. Five-milliliter aliquots were harvested by centrifugation (10 min at 7800g). Pellets were frozen until sampling was completed. Pellets were then thawed on ice and resuspended in 5 ml of protoplasting buffer (15 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 0.45 m sucrose, 8 mm EDTA). To this was added 40 μl of 50 mg/ml lysozyme and samples were incubated on ice for 15 min. Protoplasts were collected by centrifugation (5 min at 3800g). Samples were then resuspended in 0.5 ml of lysing buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 10 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na-citrate, 1.5% SDS) and 15 μl of dimethylpyrocarbonate. Samples were mixed gently and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Protein was precipitated by chilling on ice, adding 250 μl of saturated NaCl, incubating for 10 min on ice, and centrifuging for 10 min. RNA was ethanol precipitated overnight at −20°C, washed with 80% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 100 μl of dH2O. RNA was quantified on a spectrophotometer at 260 nm and 1.0 μg was loaded onto a slot blot. The membranes were probed with a digoxigenin-labeled AccI–HindIII DNA fragment from the socE gene (E.W. Crawford and L.J. Shimkets, in prep.).

Pseudorevertant analysis

Pseudorevertants of LS2125 that grow following SocE depletion were induced by UV light or Tn5-132 insertion. For UV mutagenesis, an exponentially growing LS2125 culture was pelleted and resuspended in TM buffer (10 mm Tris at pH 7.6, 1 mm MgSO4) to a final cell density of 109 cells/ml. The cell suspension was exposed to UV light at 1500 μW/cm2 for 15 sec with a germicidal UV lamp, killing 95%–99% of the cells. The mutagenized cells were diluted 1:10 in CYE broth plus 50 μg/ml kanamycin and aliquoted into 2-ml pools that were incubated in the dark. Pools were examined for turbidity at 12-hr intervals. Turbid cultures were streaked for isolation on CYE agar, and one-well isolated colony was saved from each pool. UV-induced pseudorevertants were isolated at a frequency of ∼1.6 × 10−7.

Transposon-induced pseudorevertants were isolated by infecting LS2125 with P1 Tn5-132 (Kuner and Kaiser 1981). P1 Tn5-132 was mixed with 108 cells at a MOI of 1.0. After 20 min the mixture was spread onto CYE agar containing 8 μg/ml oxytetracycline and incubated in the dark. Plates were overlaid with oxytetracycline 12 hr later to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml.

Pseudorevertants were examined for the ability of csgA+ or relA+ to restore growth arrest upon SocE depletion. pGC65, a trimethoprim-resistant derivative of the integrative vector pLJS60 (Li and Shimkets 1988), was constructed by digesting chromosomal DNA from LS429, a strain of M. xanthus containing a Tn5–Tp (Sasakawa and Yoshikawa 1987) insertion, with EcoRI and HindIII. A 2.0-kb fragment containing the trimethoprim-resistance marker was ligated into the HindIII–EcoRI site of pLJS60. The ligation was electroporated into E. coli XLI, selecting trimethoprim resistance. The resulting plasmid was digested with HindIII, mixed with either a 3.9-kb HindIII fragment from pLJS69 (Shimkets and Rafiee 1990) that contains csgA (yielding pGC66) or a 2.7-kb HindIII fragment from pMS132 (Harris et al. 1998) that contains E. coli relA under control of phv (yielding pGC67).

The csgA-containing plasmid (pGC66) was electroporated into each of the pseudorevertants, selecting trimethoprim resistance, on CYE agar plus 250 μg/ml trimethoprim in the light. Electroporants were grown in CYE broth in the light in the presence of trimethoprim and shifted to the dark, and their growth monitored. The three pseudorevertants that were not complemented by csgA were electroporated with the relA plasmid pGC67, selecting trimethoprim resistance in the light. Electroporants were grown in CYE broth in the light before being shifted to the dark.

Southern hybridization confirmed that LS2133 and LS2134 contain Tn5 insertions in relA and that L2130, LS2131, LS2132, LS2135, LS2136, and LS2137 contain Tn5 insertions in csgA (data not shown). Inverse PCR was performed on chromosomal DNA from two of the relA-complemented strains using Tn5-specific primers. The resultant PCR products were cloned and sequenced to define the precise insertion sites in relA. DNA flanking the Tn5-132 insertions in pseudorevertants LS2133 and LS2134 was cloned by inverse PCR (Ochman et al. 1988) using Tn5 specific primers GGTTCCGTTCAGGACGCTAC and GGTGATCCTCGCCGTACTGC. The resulting 310-bp (from LS2133) and 260-bp (from LS2134) products were cloned into pUC19 and sequenced.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB9601077. We thank C. Kelloes and M. Farmer for help with the electron microscopy. We also thank K. O'Connor, D. Zusman, M. Cashel, M. Singer, and D. Hodgson for providing strains used in this work. We are grateful to D. Kearns and R. Phillips for critical reading of this manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL shimkets@arches.uga.edu; FAX (706) 542-2674.

References

- Bullock WO, Fernandez JM, Short JM. XL1-Blue: A high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. Biotechniques. 1987;5:376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JM, Geisselsoder J, Zusman DR. Isolation of bacteriophage MX4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1978;119:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashel M. Detection of (p)ppGpp accumulation patterns in Escherichia coli mutants. In: Dolph KW, editor. Methods in molecular genetics. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Cashel M, Gentry D, Hernandez J, Vinella D. The stringent response. In: Neidhart FC, editor. Escherchia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1458–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Downard J, Ramaswamy SV, Kil K-S. Identification of esg, a genetic locus involved in cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7762–7770. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7762-7770.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin M. Recent advances in the social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:70–102. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.70-102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin M, Gibson SM. A system for studying microbial morphogenesis: Rapid formation of microcysts in Myxococcus xanthus. Science. 1964;146:243–244. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3641.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin M, Niederpruem DJ. Electron transport system in vegetative cells and microcysts of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1964;87:316–322. doi: 10.1128/jb.87.2.316-322.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollop R, Inouye M, Inouye S. Protein U, a late-developmental spore coat protein of M. xanthus, is a secretory protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3597–3600. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3597-3600.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen DC, Bretscher AP, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenetic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Devel Biol. 1978;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris BZ, Kaiser D, Singer M. The guanosine nucleotide (p)ppGpp initiates development and A-factor production in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1022–1035. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson DA. Light-induced carotenogenesis in Myxococcus xanthus: Genetic analysis of the carR region. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:471–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye M, Inouye S, Zusman D R. Biosynthesis and self-assembly of protein S, a development-specific protein of Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1979;76:209–213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser D. Bacteria also vote. Science. 1996;272:1598–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Kaiser D. C-factor: A cell-cell signaling protein required for fruiting body morphogenesis of Myxococcus xanthus. Cell. 1990a;61:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90211-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Cell alignment required in differentiation of M. xanthus. Science. 1990b;249:926–928. doi: 10.1126/science.2118274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— C-Factor has distinct aggregation and sporulation thresholds during Myxococcus development. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1722–1728. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1722-1728.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroos L, Kaiser D. Expression of many developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus depends on a sequence of cell interactions. Genes & Dev. 1987;1:840–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuner JM, Kaiser D. Introduction of transposon Tn5 into Myxococcus for analysis of developmental and other nonselectable mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1981;78:425–429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuspa A, Plamann L, Kaiser D. Identification of heat-stable A-factor from Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3319–3326. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3319-3326.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRossa R, Kuner J, Hagan D, Manoil C, Kaiser D. Developmental cell interactions of Myxococcus xanthus: Analysis of mutants. JBacteriol. 1983;153:1394–1404. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1394-1404.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B-U, Lee K, Mendez J, Shimkets LJ. A tactile sensory system of Myxococcus xanthus involves an extracellular NAD(P)+-containing protein. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:2964–2973. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Shimkets LJ. Site-specific integration and expression of a developmental promoter in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5552–5556. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5552-5556.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SF, Shimkets LJ. Effect of dsp mutations on the cell-to-cell transmission of CsgA in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3648–3652. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3648-3652.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Lee B, Shimkets LJ. csgA expression entrains Myxococcus xanthus development. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:401–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoil C, Kaiser D. Accumulation of guanosine tetraphosphate and guanosine pentaphosphate in Myxococcus xanthus during starvation and myxospore formation. J Bacteriol. 1980a;141:297–304. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.1.297-304.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Guanosine pentaphosphate and guanosine tetraphosphate accumulation and induction of Myxococcus xanthus fruiting body development. J Bacteriol. 1980b;141:305–315. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.1.305-315.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Purine-containing compounds, including cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate, induce fruiting of Myxococcus xanthus by nutritional imbalance. J Bacteriol. 1980c;141:374–377. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.1.374-377.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary W, Esmon B, Zusman D. M. xanthus protein C is a major spore surface protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2141–2145. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2141-2145.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H, Gerber AS, Hartl DL. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction. Genetics. 1988;120:621–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor K, Zusman D. Development in M. xanthus involves differentiation into two cell types, peripheral rods and spores. J Bacteriol. 1991a;173:3318–3333. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3318-3333.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Behavior of peripheral rods and their role in the life cycle of M. xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1991b;173:3342–3355. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3342-3355.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani M, Kozaku S, Xu C, Umezawa C, Sano K, Inouye S. Protein W, a spore-specific protein in Myxococcus xanthus, formation of a large electron-dense particle in a spore. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:57–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson B, Krook M, Jornvall H. Characteristics of short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases and related enzymes. Eur J Biochem. 1991;200:537–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plamann L, Kaplan HB. Cell-density sensing during early development in Myxococcus xanthus. In: Dunny DM, Winans SC, editors. Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Plamann L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. Proteins that rescue A-signal-defective mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3311–3318. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3311-3318.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey WS, Dworkin M. Microcyst germination in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:2249–2257. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.6.2249-2257.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhie HG, Shimkets LJ. Developmental bypass suppression of Myxococcus xanthus csgA mutations. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3268–3276. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3268-3276.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager B, Kaiser D. Intercellular C-signaling and the traveling waves of Myxococcus. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2793–2804. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa M. A series of Tn5 variants with various drug-resistance markers and suicide vector for transposon mutagenesis. Gene. 1987;56:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimkets LJ. Intercellular signaling during fruiting-body development of Myxococcus xanthus. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:525–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimkets LJ, Asher SJ. Use of recombination techniques to examine the structure of the csg locus of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol & Gen Genet. 1988;211:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00338394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimkets LJ, Kaiser D. Induction of coordinated movement of Myxococcus xanthus cells. J Bacteriol. 1982a;152:451–461. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.1.451-461.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Murein components rescue developmental sporulation of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1982b;152:462–470. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.1.462-470.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— . Cell contact-dependent C signaling in Myxococcus xanthus. In: Dunny DM, Winans SC, editors. Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shimkets L, Rafiee H. CsgA, an extracellular protein essential for M. xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5299–5306. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5299-5306.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Kaiser D. Ectopic production of guanosine penta- and tetraphosphate can initiate early developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1633–1644. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogaard-Anderson L, Kaiser D. C factor, a cell-surface-associated intercellular signaling protein, stimulates the cytoplasmic Frz signal transduction system in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:2625–2679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt BG, Hedge PJ, Heesey ST, Edelman A, Broome-Smith JK. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wireman JW, Dworkin M. Morphogenesis and developmental interactions in myxobacteria. Science. 1975;189:516–522. doi: 10.1126/science.806967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Developmentally induced autolysis during fruiting body formation by Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:796–802. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.2.798-802.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zusman D, Rosenberg E. DNA cycle of Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1970;49:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Division cycle of Myxococcus xanthus-II. Kinetics of stable and unstable RNA synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1971;105:801–810. doi: 10.1128/jb.105.3.801-810.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]